Abstract

This article explores how teachers’ professional learning about the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR) can re-orient their reported teaching practices to meet learner-identified sociolinguistic needs. To this end, the article first examines learners’ sociolinguistic needs by exploring the extent to which post-secondary French-as-a-second-language (FSL) learners, who completed their elementary and secondary schooling in Ontario, Canada, believe that they have successfully developed sociolinguistic competence in their target language. Specifically, it considers the learners’ assessment of their sociolinguistic abilities, the types of sociolinguistic skills they wish to develop further, a comparison with their actual sociolinguistic performance, and the ways in which they hope to develop the sociolinguistic skills they feel they lack. Second, the article explores Ontario elementary- and secondary-school FSL teachers’ reported focus on sociolinguistic competence in their teaching after having engaged in intensive and extensive CEFR-oriented professional learning. Specifically, it considers how the teachers’ professional learning influences the sociolinguistic relevance of their planning, classroom practice, and assessment and evaluation. The article concludes by considering whether the degree of “fit” between the learners’ self-identified needs and the teachers’ reports of their re-oriented practices is poised to improve the sociolinguistic outcomes of Ontario FSL learners.

1. Introduction

Sociolinguistic agency is the “socioculturally mediated act of recognizing, interpreting, and using the social and symbolic meaning-making possibilities of language”. It is predicated on an understanding that “the use of one linguistic variant or another simultaneously reflects and creates the context in which it is used” and is “a performance of one’s social identity at the time of utterance” [1] (p. 237). As such, to help language learners enact sociolinguistic agency in their target language interactions, it is necessary to support their development of sociolinguistic competence [1,2]. Sociolinguistic competence consists of the knowledge of social contexts and the socio-stylistic value of the range of variants associated with these contexts. In the field of second language acquisition (SLA), such competence has long been recognized as an integral component of communicative competence [3]. The development of sociolinguistic competence and sociolinguistic agency is one of the explicit aims of the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR) in that it views learners as “language users and social agents” and language as “a vehicle for communication rather than as a subject to study”. To achieve this aim, the framework “proposes an analysis of learners’ needs” in order to help them develop the ability “to act in real-life situations” in a variety of social contexts [4] (p. 29).

With this aim of the CEFR in mind, the present paper addresses the following research questions in relation to the context of French-as-a-second-language (FSL) education in the Canadian province of Ontario:

- What needs do FSL learners identify concerning their development of sociolinguistic competence? Specifically:

- What are their beliefs about the extent of their sociolinguistic abilities?

- What types of sociolinguistic skills would they like to develop further?

- How do their beliefs compare to their actual sociolinguistic performance, as captured during a semi-structured interview in French?

- In what ways would they prefer to acquire the sociolinguistic skills they feel they lack?

- In what ways do FSL teachers feel that their CEFR-oriented professional learning is making sociolinguistic competence more central to their teaching practices? Specifically:

- What impacts do they report on their planning practices?

- What impacts do they report on their classroom practices?

- What impacts do they report on their assessment and evaluation practices?

- Is the degree of “fit” between the learners’ self-identified sociolinguistic needs and the teachers’ reports of their reoriented teaching practices likely to lead to increased sociolinguistic competence for Ontario FSL learners?

2. Literature Review

This review focuses, first, on the literature addressing FSL learners’ sociolinguistic development, specifically their metalinguistic knowledge and patterns of sociolinguistic variants use. It then considers the literature examining FSL teachers’ practices, particularly as concerns the CEFR in FSL teaching in Ontario, Canada, and sociolinguistically oriented FSL teaching.

2.1. FSL Learners’ Metasociolinguistic Knowledge

Studies investigating FSL learners’ metasociolinguistic knowledge have focused on exploring the effectiveness of providing learners with explicit instruction and/or engaging learners in metalinguistic reflection on the use of sociolinguistic variants. In such research, a clear distinction emerged between the knowledge of sociolinguistic variants and their actual use; in other words, between competence and performance [5,6,7]. The findings indicated that although explicit instruction was effective in helping learners develop competence, it did not automatically translate into performance. However, these studies stressed that the absence of sociolinguistic variation in the learners’ second language (L2) production did not necessarily indicate a lack of sociolinguistic awareness [1,6]. They also suggested that with appropriate pedagogical support, newly acquired sociolinguistic knowledge can result in the productive use of sociolinguistic variants over time [1].

The findings of such studies further suggested that learners need to become aware of sociolinguistic variation before they can engage in the process of developing receptive and productive knowledge of it [8]. Additionally, they suggested that it is beneficial for learners to start acquiring sociolinguistic knowledge early to avoid needing to counteract the entrenched invariable use of sociolinguistic variants at later stages [6,8]. Finally, these studies suggested that it should be expected that learners will develop personal preferences in the use of sociolinguistic variants, whether reflecting the use of variants in their educational input, their personal L2 sociolinguistic goals or their overall L2-related goals, or other factors [6,7].

2.2. Patterns of Learners’ Sociolinguistic Variant Use

In a volume synthesizing studies focused on the acquisition of sociolinguistic variants by FSL learners [9], four primary categories of variants were identified, namely vernacular variants (e.g., ’ien que, mas, nous-autres, fait que, job, rester), informal variants (e.g., juste, je vas, on, so), formal variants (e.g., seulement, je vais, nous, emploi, travail, habiter, alors, donc), and hyper-formal variants (e.g., ne…que, poste, demeurer). These variants include the following: (i) expressions of restriction meaning ‘only’ (i.e., ‘ien que/juste/seulement/ne…que), for example, il (n’)y a ‘ien que/juste/seulement/que trois autos (there are only three cars); (ii) forms of the first-person singular of the verb aller, meaning ‘to go’ (i.e., mas/je vas/je vais), for example, mas/je va/je vais te dire quoi faire (I am going to tell you what to do); (iii) first-person plural personal subject pronouns meaning ‘we’ (i.e., nous-autres/on/nous), for example, nous-autres/on/nous sommes/est ici (we are here); (iv) lexical expressions meaning ‘job’ (i.e., job/emploi/travail/poste), for example, il a trouvé un(e) job/emploi/travail/poste (he found a job); (v) lexical expressions meaning ‘to live’ (i.e., rester/habiter/demeurer), for example, je reste/habite/demeure à Toronto (I live in Toronto); and (vi) expressions of consequence meaning ‘therefore’ (i.e., fait que/so/alors/donc), for example, il est tard fait que/so/alors/donc je vais me coucher (it is late therefore I will go to bed). This synthesis revealed that classroom-instructed learners use vernacular and hyper-formal variants only marginally or not at all, informal variants less frequently than first-language (L1) speakers of French, and formal variants substantially more frequently than L1 speakers. One reason for these trends was the learners’ educational input. The learners were approximating patterns that research has documented in the in-class speech of FSL teachers and in FSL instructional materials.

A number of factors that lead to learners’ increased use of a wider array of differentially marked sociolinguistic variants have been identified in the literature. These include, in particular, increased extracurricular exposure to the authentic use of French in Francophone environments and increased long-term or targeted curricular exposure to the target language [9,10,11,12,13,14]. These factors also include increased engagement in learning French, which is measured by the frequency, intensity, intellectual demand, and immediacy of the use of French at present (e.g., current curricular and extracurricular exposure) and in the future (e.g., the intent to live and work in a Francophone environment) [15,16].

Research has also suggested that some sociolinguistic variants may be acquired more or less easily than others, as is the case with other linguistic features. For example, research focused on the acquisition of morphosyntactic features in French has revealed that important factors include the frequency with which a particular form naturally occurs in the language and the complexity of the rules governing its use [17]. Concerning the acquisition of sociolinguistic variants specifically, an additional factor can be a variant’s socio-stylistic status. For example, some studies have found that both FSL learners and teachers avoided the use of vernacular and hyper-formal variants that were strongly socially marked but made highly frequent use of many formal variants and non-negligible use of certain informal variants that were less socio-stylistically marked [9]. However, other studies have found that the Canadian regional variant of lax-i was rare in the speech of FSL learners, even though the variant is used with high frequency by L1 speakers, has a fairly easy pronunciation, and is socio-stylistically neutral [18]. (In the study, a distinction is made between a tense-i, which is pronounced categorically in open syllables and stressed syllables closed by a lengthening consonant, as in the French verbs vivre (to live) and rire (to laugh), and a lax-i, which is pronounced in stressed syllables closed by other (non-lengthening) consonants, as in the French nouns site (area) and ride (wrinkle)). This suggests that the above combination of factors is not always sufficient to make a variant easy to acquire.

Although the nature of certain sociolinguistic variants can make their acquisition more difficult, research has shown that instruction can be effective in helping learners overcome such challenges. An important and necessary step toward the acquisition of sociolinguistic variation is the learners’ awareness of its existence. Such awareness, especially if acquired through explicit, systematic, and recurrent instruction, can lead learners to develop control over sociolinguistic variant use [19]. However, research has also shown that this is not a uniform process for all learners, even within the same learning conditions [12,20]. For example, one study investigated the acquisition of three morphosyntactic sociolinguistic variables (retention/deletion of ne, nous/on, and expression of futurity) and two phonological variables (/l/ retention/deletion, liaison) by five learners of French in a study-abroad context [20]. It documented individual differences among the learners, even though they were believed to be extremely similar both in their study-abroad experience and in their attitude, motivation, and desire to learn French.

2.3. The CEFR in FSL Teaching in Ontario, Canada

The introduction of the CEFR in Canada, which is relatively recent in comparison to certain parts of the world [21], dates back to the recommendation of its use in 2006 to the Council of Ministers of Education, Canada, which officially endorsed its adoption in 2010 [22]. Initial interest in the framework is linked to one of the goals formulated by the Government of Canada in 2003 to double the proportion of English-French functionally bilingual high school graduates, with the framework serving as a primary assessment tool. Since then, the adoption of the CEFR has varied across Canada, where primary and secondary school curricula are regulated at the provincial level. In Ontario, the adoption of the framework has been aided by several province-wide movements.

One such movement concerns the development of a Framework for FSL in Ontario Schools: Kindergarten to Grade 12 [23]. In this framework, the Ontario Ministry of Education placed the CEFR at the center of FSL education in the province after recognizing the framework as “a valuable asset for informing instruction and assessment practices” (p. 4). It envisions FSL learners as having “the confidence and ability to use French effectively in their daily lives” (p. 8) by calling for the implementation of the action-oriented approach, the use of “authentic, meaningful, interactive, and relevant tasks”, and the prioritization of “the functional use of the language” (p. 18). This framework may be viewed as part of a larger province-wide movement related to the CEFR, which involves offering FSL teachers numerous professional learning opportunities designed to familiarize them with the CEFR. These opportunities include, for example, provincial CEFR-focused meetings and web conferences, regional learning events, school board conferences and workshops, self-directed and job-embedded learning, and Diplôme d’études en langue française (DELF) assessor training. The Diplôme d’études en langue française (DELF) is a CEFR-aligned exam of FSL proficiency offered at four CEFR levels: A1 and A2 (basic users), and B1 and B2 (independent users). The exam tests skills in four major areas: oral comprehension and production, and written comprehension and production. The diplomas are issued by the French Ministry for National Education. Assessors must receive specific training before they are qualified to score the DELF exam.

These types of professional learning opportunities helped to address teachers’ initial confusion about the CEFR, which they saw as a positive though challenging addition to FSL education in the province. For example, one study of Ontario teachers’ perceptions of CEFR-informed instruction conducted prior to the development of the new FSL framework in 2013 found that the teachers saw many benefits of the new approach [24]. However, they also felt that to be able to orient their teaching to the framework successfully, they needed to develop a thorough understanding of its principles and identify practical ways for applying these principles in their classroom practice. That same year, another study reported that one effective way for teachers to address these types of challenges was through professional development opportunities, such as teachers working together in groups designed as professional learning communities [25]. In this study, a group of L2 teachers in the Canadian province of New Brunswick engaged in formal and informal meetings about the CEFR. Over the course of their engagement, the teachers identified what the framework was asking them to do and how, created CEFR-informed instructional materials, and designed a plan for their implementation.

Another CEFR-related movement in Ontario has been to encourage graduating Grade 12 students to take the DELF. A study of Grade 12 students’ DELF results showed that their areas of greatest strength were written comprehension skills and, within their productive skills, the ability to follow instructions and provide information [26]. In contrast, oral comprehension skills and written and oral production skills, particularly their application of grammar and vocabulary in context, were identified as the areas in greatest need of improvement. The study explored the link between the students’ test results and their confidence in their French skills and found that the students were generally more confident about their receptive than their productive skills, more confident about their written than their oral skills, and, specifically, that they felt most confident about their reading skills and least confident about their conversational skills. The results thus showed that speaking skills were an area that the students needed to improve in terms of both proficiency and confidence.

The push toward the DELF in Ontario has meant that the teachers who undertake the training to serve as DELF assessors develop a solid understanding of the CEFR. For example, the majority of teachers in one study reported that the listening, speaking, reading, and writing tasks they use in their classrooms were similar to those found on the DELF test [27]. The teachers’ comments further revealed that they believed their understanding of the DELF and the CEFR has made them focus more on helping their students develop oral comprehension skills and use more activities that are oral, interactive, and require the use of critical thinking skills. In terms of assessment, the teachers believed that knowledge of the test’s benchmarks helped them understand more clearly what their students were expected to be able to do in French at various levels of proficiency.

Finally, learners, for their part, have also been found to positively view the type of instruction that the CEFR promotes. A study exploring Grade 12 students’ preferences in L2 learning found that the students prioritized as a goal the ability to use the target language in the real world [28]. They believed that L2 instruction should be focused on helping them develop skills that are practical and applicable outside of the classroom. They reported that one way to bring the real world into the classroom was to use authentic L2 materials, such as music videos, news, or interviews, which they saw as useful in exposing them to different varieties of the language and to ‘slang’.

2.4. Sociolinguistically-Oriented FSL Teaching

Studies exploring effective approaches to the development of classroom-based FSL learners’ sociolinguistic competence have suggested that explicit instruction is necessary and is most effective when integrated in the curriculum so that its delivery is systematic and recurrent and follows the awareness-practice-feedback sequence [14,19]. There is evidence to suggest that such explicit instruction is possible and desirable even with lower-proficiency learners [29]. It does not appear to be overwhelming for new learners and has the advantage of preventing learners from developing habits of invariant use that may be difficult to counteract later [30]. Studies also show that the effectiveness of explicit instruction is increased, first, if the focus is placed primarily on teaching learners to understand sociolinguistic variation “conceptually” rather than on acquiring rigid rules for the use of specific sociolinguistic variants [31]. Second, it is increased when learners are allowed to develop a personal stance toward the sociolinguistic concepts they are acquiring. Such an approach allows learners, on the one hand, to apply their sociolinguistic knowledge (such as understanding the link between formality and social distance) more broadly and, on the other hand, to enact their sociolinguistic agency by making choices that reflect their current personal or social identity. Concerning the use of authentic materials, the use of films and the process of scriptwriting have been proposed, as well as more recently the use of television series and subtitles [32]. These allow learners to observe a character’s choice of sociolinguistic variants in interactions that differ in terms of their conversation partner, setting, and communication purpose—importantly, also at various stages of relationship development.

2.5. Links to the Present Study

As we have seen, the CEFR calls for the analysis of learners’ needs with the aim of helping them develop the ability to act in real-life situations. This ability relies on their capacity to enact their sociolinguistic agency. Supporting learners in this endeavor can be accomplished through pedagogical approaches that prioritize the use of authentic materials and communicative tasks modeled on real-world interactions. For this reason, the present article, as mentioned, draws on learner and teacher data to explore the extent to which the learners’ self-identified sociolinguistic needs align with the teachers’ self-reported reoriented practices following CEFR-oriented professional learning.

3. Methods

The present study draws on datasets collected as part of two larger projects. The first project examined the sociolinguistic knowledge base of Ontario FSL learners at the university level. Using data from university-level learners for the present study offers the advantage of students who can provide a retrospective perspective on their entire FSL journey, from Kindergarten to Grade 12, and beyond. The second project examined the impact of CEFR-informed professional learning on the pedagogical practice of Ontario FSL teachers from Kindergarten to Grade 12. Details of these two datasets are presented below.

3.1. Learners

The learner data referenced in this article and summarized in Table 1 were collected in 2012 from 44 undergraduate students in years one through five at two Canadian universities—26 at an English-medium institution and 18 at an English/French bilingual one. The 44 students represent a non-probabilistic convenience sample of students who were enrolled in undergraduate FSL courses, either as part of a French Major or French Specialist program, and had studied French at elementary or secondary schools in Ontario in French immersion programs or non-immersion programs.

Table 1.

Distribution of FSL Learners.

Two data collection instruments were used: an English interview and a French interview. The English interview that the students participated in was an ad hoc semi-directed interview, in which they answered questions about what they know about levels of formality in French, how they learned about such (in)formality, what else they would like to know about this topic, and how their FSL courses could better develop their sociolinguistic abilities. The English interview also asked the following specific questions:

- What do you know about sociolinguistic variation in French (including any specific sociolinguistic variants you know, and how you acquired them)?

- To what extent do you feel able to perceive the identity and intentions of others in French?

- To what extent do you feel able to express your own identity and intentions in French?

The French interview that the students participated in was a semi-directed interview in French. Following the standard methodology of previous sociolinguistic research [9,10,13], the present study used this French interview to examine the students’ use of sociolinguistic variants. The list of interview questions was drawn from previous sociolinguistic research [9]. These questions broached a variety of formal topics, such as the importance of religion in their life, their views on political issues, and their views about different regional varieties of French. They also addressed a variety of informal topics, such as what television programs they enjoy watching, a funny trick they played on a teacher, and plans for summer vacation.

3.2. Teachers

The teacher data referenced in this article were collected in 2017. Thirty-six Ontario school boards were each asked to invite five teachers to participate in a study exploring the practices of teachers who had participated in CEFR-related professional development opportunities. The participating teachers from this non-probabilistic sample are, thus, likely to be those who are the most positively oriented to the CEFR and who had made the greatest efforts to align their teaching practices with the framework. A total of 103 teachers responded to this call. The teachers taught in Core French programs (i.e., where French is the subject of study), French Immersion programs (i.e., where French is the medium of instruction for other subject areas), and/or Extended French programs (i.e., a type of intensive French program akin to delayed-immersion and preceded by Core French courses). As Table 2 shows, they are elementary and secondary school teachers teaching FSL classes at multiple grade levels from Kindergarten (students aged three to five years old) to Grade 12 (students aged 17 or 18 years old).

Table 2.

Grades Taught by FSL Teachers.

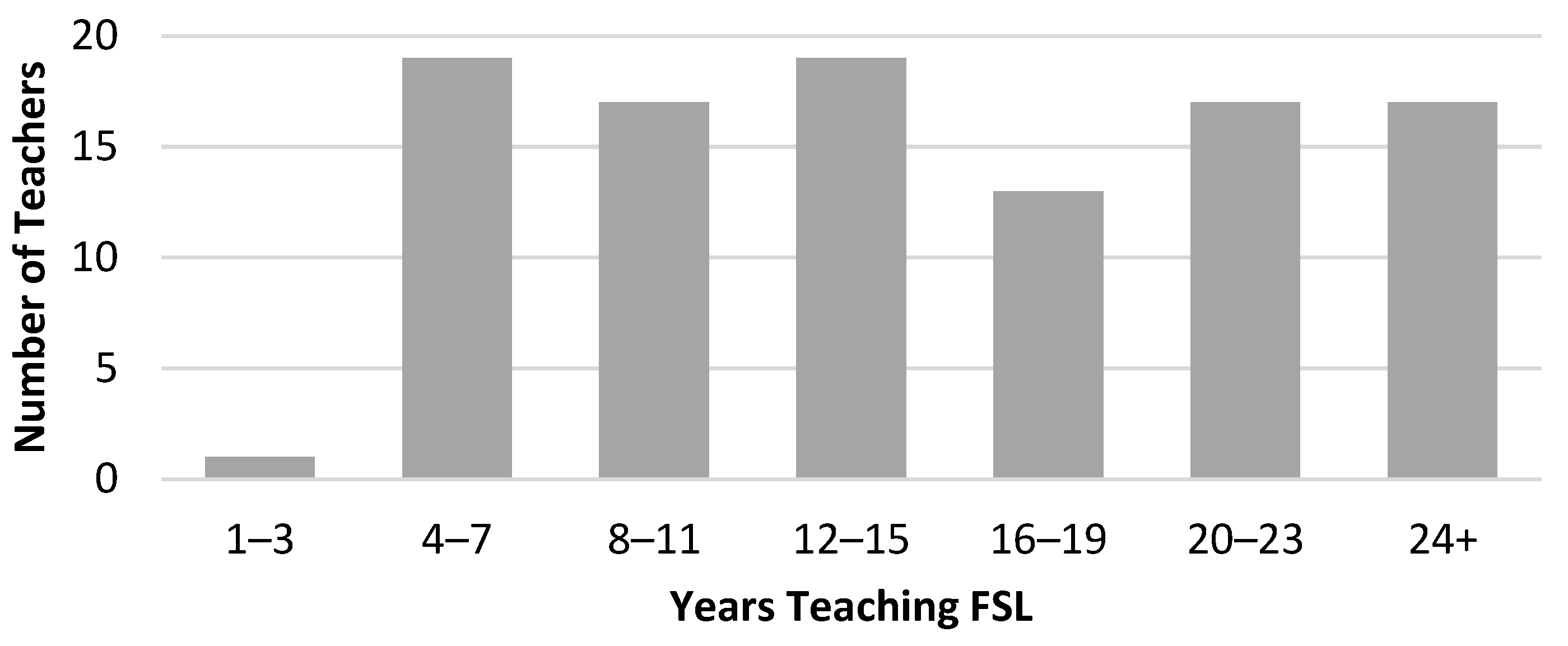

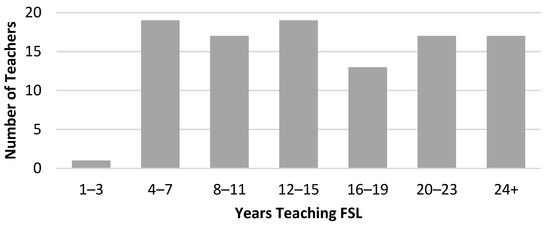

As can be seen in Figure 1, the teachers were fairly evenly distributed based on their number of years of FSL teaching experience, except for a dearth of novice teachers.

Figure 1.

FSL Teachers’ Years of Teaching Experience.

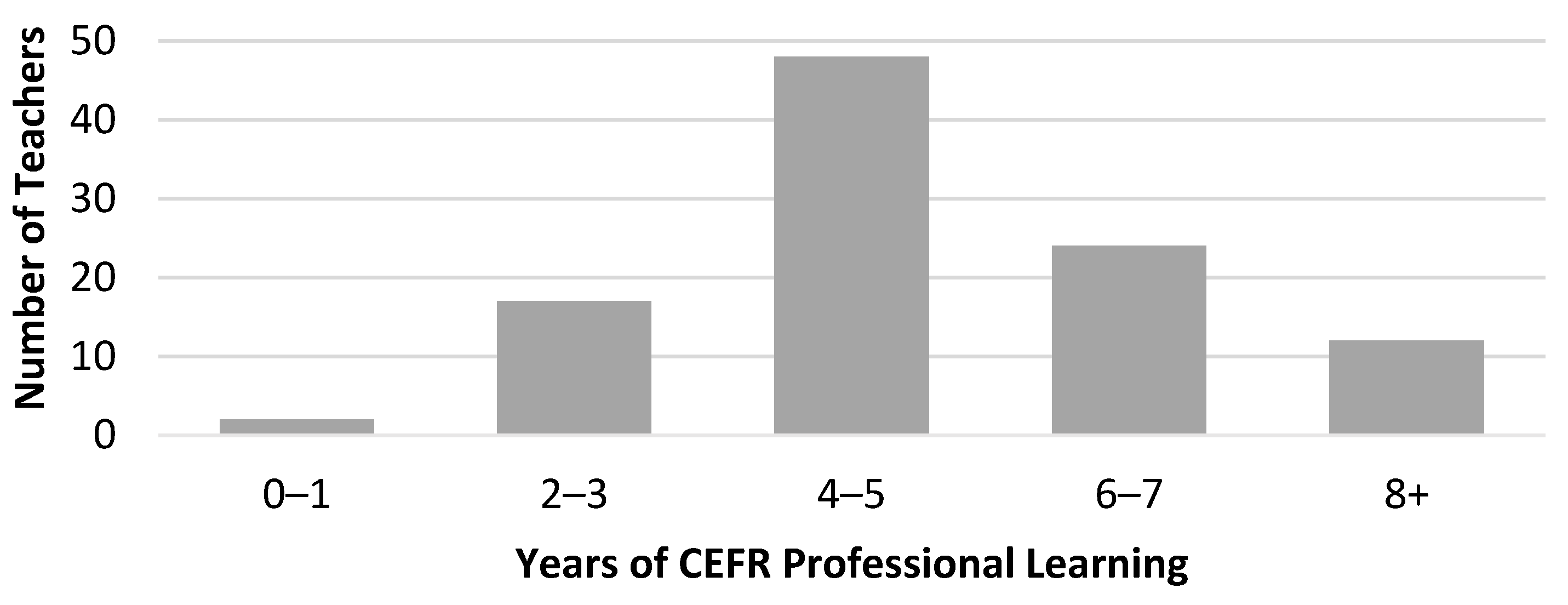

Figure 2 shows that the majority of the teachers reported having participated in CEFR-related professional learning for four years or more, with approximately half reporting four to five years of such training.

Figure 2.

FSL Teachers’ Years of CEFR-Related Professional Learning.

As shown in Table 3, all of the teachers had completed DELF corrector training and nearly all had attended CEFR-related conferences and/or workshops hosted by their schools or their Boards as part of their array of CEFR-related professional learning experiences.

Table 3.

FSL Teachers’ Professional Learning Opportunities.

Each of the 103 teachers completed a two-part online survey. The first part asked them to provide information about their teaching experience (e.g., grades taught and number of years of teaching experience) and their CEFR-related professional learning (e.g., the number of years and types of CEFR-related professional learning). The second part of the survey asked them to provide self-reports about their teaching practices before (i.e., retrospectively) versus after (i.e., currently) their CEFR-related professional learning. The survey tapped their practices concerning planning, classroom delivery, and assessment and evaluation. With respect to their planning practices, the teachers were asked to comment on how they approached developing their students’ proficiency and what proportion of time they devoted to each of the four basic skills. They were also asked about what aspects of the CEFR they considered most important, how their experience scoring the DELF exam improved their understanding of the CEFR and impacted their FSL planning, and what changes they had made to their FSL teaching resources. In regard to their classroom delivery, the teachers were invited to reflect on the extent to which they used a variety of traditional practices (e.g., immediate error correction, a focus on forms) versus CEFR-informed practices (e.g., activities related to everyday life, student-driven needs analysis). They were also asked about the balance they placed across linguistic, sociolinguistic, and pragmatic competences; how they presented language in their classrooms; and the effective activities they used to teach grammar and vocabulary and encourage authentic and spontaneous student-to-student interaction. This section of the survey ended with a question asking the teachers to identify a change in their practice that they felt had the most impact on increasing their students’ proficiency. Finally, with respect to their assessment and evaluation practices, the teachers were asked a series of questions about whether learning goals, success criteria, and feedback prioritized form versus function, and about the aspects targeted in their feedback. The teachers were also asked what proportion of their summative evaluations they devoted to each of the four skills and which change in their assessment practices they believed had the greatest impact on increasing their students’ proficiency.

3.3. Data Analysis

This study adopts a qualitative approach to the analysis of the data, allowing for the emergence of themes or categories within the students’ and teachers’ responses, as reported in the results section. This approach is supplemented, where appropriate, with descriptive statistics in the form of raw numbers and percentages. Since the goal of this qualitative study is to compare the students’ self-identified needs and the teachers’ self-reported practices, rather than identifying differences across subgroups within each dataset, a statistical analysis has not been pursued.

4. Results

The results are presented below in response to the three research questions guiding the present study. First, the results related to the learners’ self-identified sociolinguistic abilities and needs are reported. Then, the results related to the teachers’ self-reports about their CEFR-informed teaching practices are presented. Finally, the extent of the match between the learners’ self-identified sociolinguistic needs and the teachers’ reports of their re-oriented practice is discussed.

4.1. Research Question #1: Learners’ Self-Identified Sociolinguistic Abilities and Needs

4.1.1. Ability to Express One’s Own Identity and Intentions and Perceive That of Other French Speakers

As Table 4 shows, despite having studied French between 10 and 18 years at the elementary and secondary school level, only half (50%) of the students reported feeling as though they had developed both the ability to express their own identity and intentions in French and the ability to perceive the identity and intentions of other French speakers. Less than half (42%) of the students reported having developed only the receptive ability, and 8% reported not having developed either of the two abilities. The students who felt they had developed both abilities pointed to their capacity to discern other speakers’ attitudes and highlighted their ability to express their personality through their linguistic choices. The students who had developed only the receptive ability reported that when it came to their expressive ability, they had to prioritize the communication of their message over that of their personality. Finally, the students who felt they had not developed either ability commented explicitly about not being familiar with vocabulary that shows a speaker’s personality and/or reported that they needed to devote their attention primarily to ensuring their ideas were understood.

Table 4.

Distribution of Learners by Self-reported Ability to Express and Perceive Identity and Intentions in French.

4.1.2. Elements Learners Report Missing to Develop Their Expressive and/or Receptive Sociolinguistic Ability

Table 5 summarizes the missing elements that the learners identified as obstacles to being able to develop their expressive and/or receptive sociolinguistic abilities in French (i.e., the ability to express their own identity and intentions and perceive that of other French speakers). Their responses revealed that in addition to a lack of confidence, they believed a major issue was their lack of knowledge of stylistically varied vocabulary, particularly with regard to the very formal and very informal registers, including an understanding of their appropriate and nuanced use according to the context.

Table 5.

Learner-Identified Missing Elements Preventing Development of Expressive and Perceptive Sociolinguistic Ability.

4.1.3. Learners’ Perceptions of Their Ability to Use Upper and Lower Register Markers

The learners’ frequency of use of vernacular, informal, formal, and hyper-formal variants during their French-language interview was measured according to their self-reported French proficiency level. Six sociolinguistic variables were examined:

- Expressions of restriction meaning “only” (i.e., ‘ien que/juste/seulement/ne…que);

- First person singular of the verb aller “to go” (i.e., mas/je vas/je vais);

- First person plural personal subject pronouns (i.e., nous-autres/on/nous);

- Lexical expressions for a “job” (i.e., job/emploi/travail/poste);

- Lexical expressions for “to live” (i.e., rester/habiter/demeurer);

- Expressions of consequence meaning “therefore” (i.e., fait que/so/alors/donc).

The students’ French proficiency was arrived at using their self-assessments of how well they felt they could speak, listen, read, and write in French using a five-point scale for each ability (one = not at all, two = a little, three = fairly well, four = very well, five = fluently). Each student’s reported fluency for the four language abilities were combined to provide a total out of 20 points, and students were regrouped into the following proficiency levels: low (4–8 points), mid (9–15 points), or high (16–20 points).

As Table 6 shows, the students predominantly used the formal variants regardless of their self-reported level of proficiency (53–64%). The students who rated their French proficiency the highest made the greatest use of informal variants (45% versus 37/35%). As for the hyper-formal and vernacular variants, the students made nil to marginal use of these regardless of their proficiency level. These results are consistent with the students’ self-reported lack of knowledge of different registers in French, particularly with regard to very formal and very informal vocabulary in French (see Table 5).

Table 6.

Learners’ Use of Sociolinguistic Variants According to their Self-Rated French Proficiency.

4.1.4. Learners’ Preferred Ways of Developing Sociolinguistic Abilities

Table 7 summarizes what the learners reported about how they would prefer to develop their sociolinguistic abilities in French. Their responses show that they would welcome more of a sociolinguistic focus in their French classes, particularly to practice speaking and listening at both the high school and university levels. They also pointed to a desire for supervised conversations and speaking activities that would encourage them to speak both within and outside of class. The use of authentic interactions and authentic materials was also high on their list of desired ways to develop their sociolinguistic abilities. For instance, students identified interacting with French speakers and watching movies with no subtitles as important means to improve this aspect of the target language. Finally, students expressed a desire to access more exchange programs and immersive experiences as a way to improve their sociolinguistic abilities, noting that there is “no substitute” for out-of-class exposure.

Table 7.

Learner-Identified Preferred Ways of Developing Sociolinguistic Abilities.

In sum, the learners’ self-assessments of their sociolinguistic competence revealed that only half of them believed they had developed the ability to both express their own identity and intentions and perceive that of other French speakers. Students also believed that they lacked knowledge of very formal and very informal vocabulary in French, which was confirmed by their preference for the use of formal sociolinguistic variants in their speech. To address the gap in their knowledge of stylistically-varied vocabulary and to improve their sociolinguistic skills in general, the students expressed a preference for an increased amount of supervised conversation and speaking activities, the use of authentic instructional materials, and opportunities to engage in authentic interactions. To gain a sense of how well these learners’ self-identified needs can be met by instructional practices informed by CEFR principles, in the following section we explore the importance of sociolinguistic competence in the teachers’ self-reports of their CEFR-informed approach to planning, classroom practice, and assessment and evaluation.

4.2. Research Question #2: Teachers’ CEFR-Informed Instructional Practices

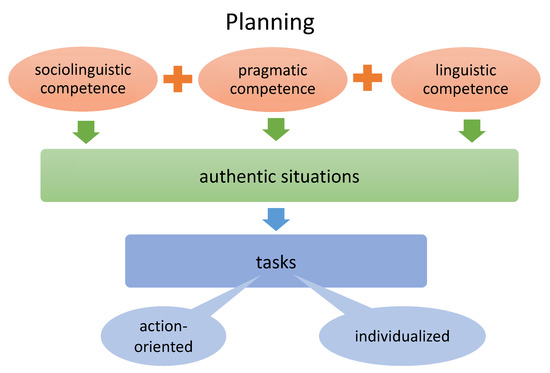

4.2.1. Teachers’ Self-Reported CEFR-Informed Approach to Planning

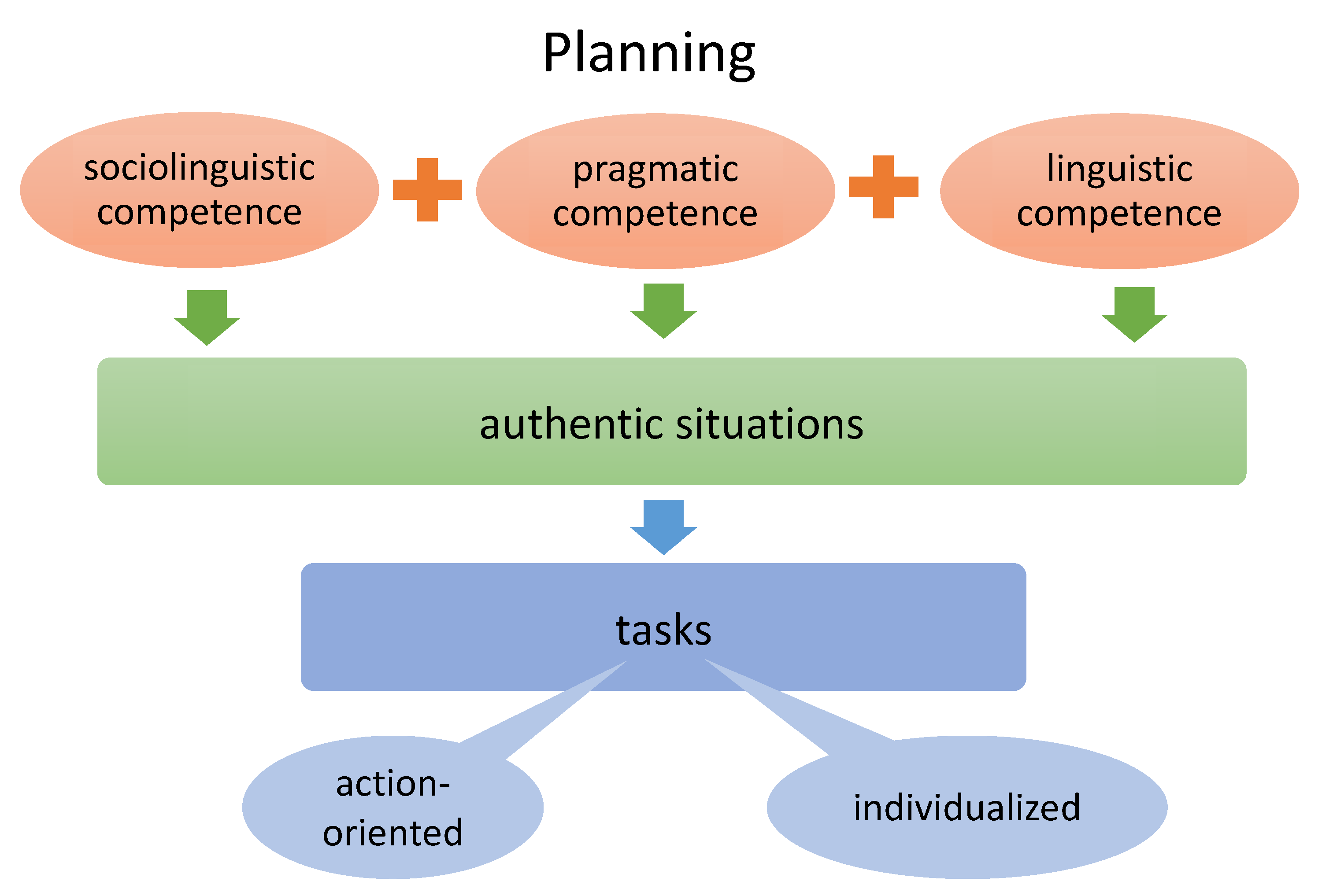

As Figure 3 illustrates, the teachers reported that their CEFR-related professional learning has encouraged them to plan for instruction that places a more balanced focus on sociolinguistic, pragmatic, and linguistic competence using authentic communicative situations presented in tasks that are action-oriented and individualized. Action-oriented tasks are authentic, open-ended, and involve meaningful interaction. For example, one teacher reported that they use tasks that “incorporate open-ended situations where [the students] have to give their opinions. When an issue has a personal connection to the students, they want to share their ideas and thoughts on the matter”. This more balanced focus on all three major competences replaced the teachers’ reported previous focus on primarily developing their students’ linguistic competence, especially through the prioritization of written skills and grammatical forms. For example, one teacher reported, “I am less strict with certain structures and focus more on [the students’] communicative ability”.

Figure 3.

Teachers’ Self-Reported CEFR-oriented Approach to Planning.

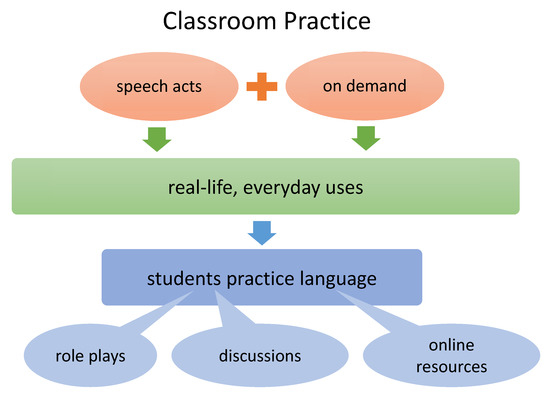

4.2.2. Teachers’ Self-Reported CEFR-Informed Approach to Teaching

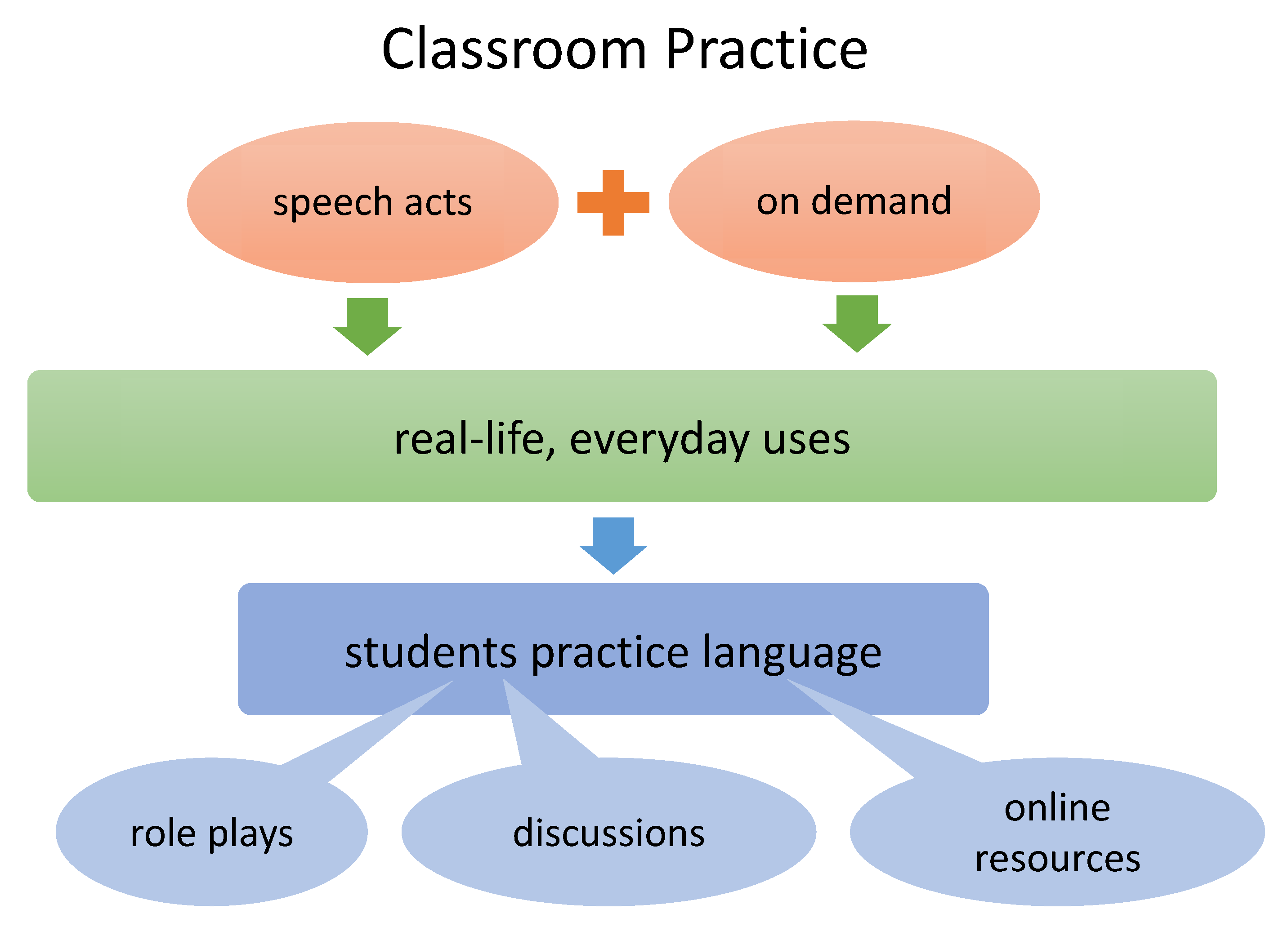

As summarized in Figure 4, the teachers reported that in their teaching, their CEFR-related professional learning inspired them to present language in relation to speech acts and on-demand by focusing on real-life, everyday uses of French. This provides their students with more opportunities to practice using the language in tasks that are sociolinguistically relevant (e.g., role-plays, structured and unstructured discussions), and to make use of online resources, such as a variety of authentic documents that exemplify stylistic varieties. For example, one teacher reported, “Going shopping in a store—this role-playing activity is a good time to review vocabulary associated with clothing, sizing, money, conditional tense (polite requests), asking questions”. Another teacher reported, “Opinion sharing in small group situations with little or no preparation—however, they do have access to a guide-sheet with specific sociolinguistic structures of focus”. This new approach to introducing language situated in real-life contexts replaced the teachers’ reported previous approach to presenting language that was theme-based, isolated, and disconnected.

Figure 4.

Teachers’ Self-Reported CEFR-oriented Approach to Teaching.

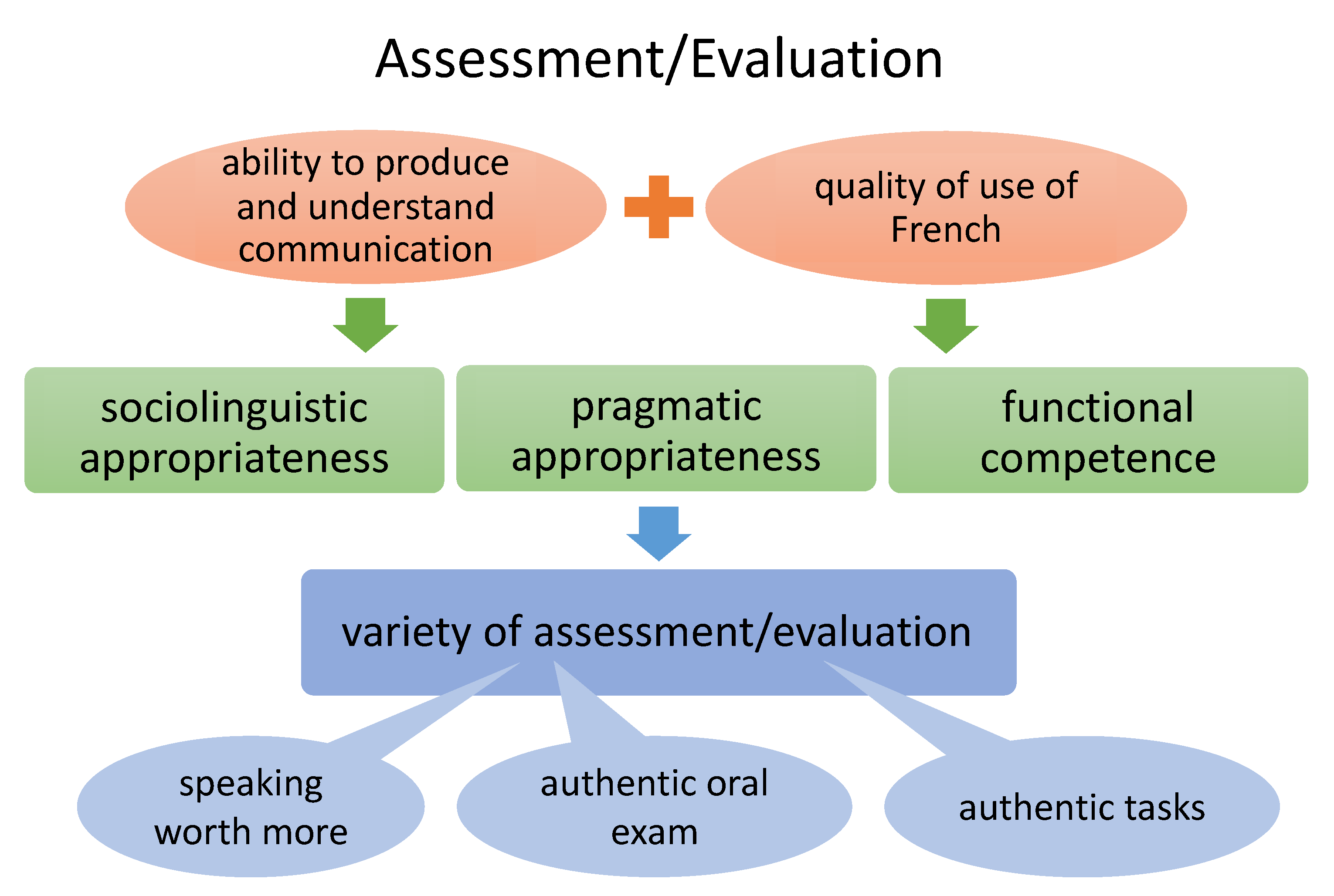

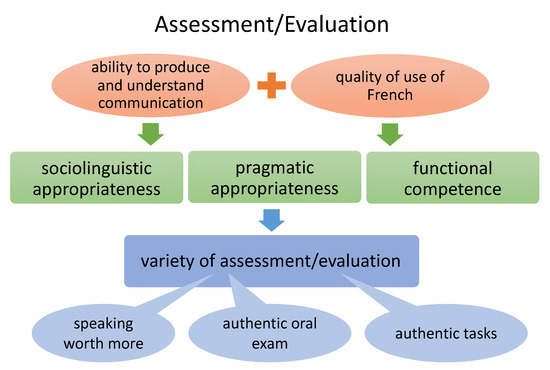

4.2.3. Teachers’ Self-Reported CEFR-Informed Approach to Assessment and Evaluation

As can be seen in Figure 5, the teachers reported that their CEFR-related professional learning led them to focus their assessment and evaluation on their students’ ability to produce and understand communication in French and on the quality of their use of the language. They reported that this new approach is reflected in their attention to sociolinguistic appropriateness, pragmatic appropriateness, and functional competence, as well as in their use of a variety of assessment and evaluation strategies. These include, among others, assigning speaking a more prominent role, using a variety of test formats, and creating authentic oral exams and other authentic assessment and evaluation tasks. For example, one teacher reported that their new approach consisted of “carefully designing authentic tasks and selecting specific success criteria”. Concerning speaking, one teacher not only reported a change in their approach, but also commented on one of the benefits that they perceived in this new approach: “Making speaking worth more has not only increased the students’ marks, but also their confidence”. This benefit corresponds directly to a lack of confidence, which was one of the learner-identified obstacles in relation to their development of sociolinguistic abilities (see Table 5). The teachers’ new expanded and varied approach to assessment and evaluation replaced their previous reported attention to orthographic control, grammatical accuracy, and phonological control.

Figure 5.

Teachers’ Self-Reported CEFR-oriented Approach to Assessment and Evaluation.

In sum, the teachers’ self-reports of the place of sociolinguistic competence in their CEFR-informed approach to planning, classroom practice, and assessment and evaluation revealed that they prioritize helping their students develop the ability to communicate in French by focusing not only on developing their linguistic competence, but also their ability to express themselves in sociolinguistically and pragmatically appropriate ways. To this end, the teachers reported increasing the prominence of speaking skills, working with authentic documents that expose their students to real-life varieties of French, and using activities that allow their students to practice communicating in authentic interactions.

4.3. Research Question #3: Overlap between Learners’ Sociolinguistic Needs and Teachers’ CEFR Practices

In this section, we explore how well these teachers’ CEFR-informed instructional practices meet the learners’ self-identified sociolinguistic needs. Table 8 summarizes both the “what” and “how” of the learners’ self-identified sociolinguistic needs and the teachers’ self-reported CEFR-informed instructional practices. As can be seen, the overlap between the learners’ needs and the teachers’ reoriented practices is considerable. In terms of the “what”, the learner-identified need to develop sociolinguistic confidence is matched by the teachers’ reported attention to develop their students’ ability to understand and engage in communication in French through a focus on students’ communication needs and via speech acts. Similarly, the students’ desire to learn how to express themselves (in)formally in contextually appropriate ways through the use of variants ranging from vernacular variants, slang, and colloquial expressions to hyper-formal variants, is matched by the teachers’ reported re-balancing of their focus to include sociolinguistic and pragmatic competences, alongside linguistic competence. In these ways, both groups are oriented to developing students’ sociolinguistic competence, including various abilities and skills, and particularly the ability to use and understand the full scale of sociolinguistic variants in French.

Table 8.

Extent of Match between Learners’ Sociolinguistic Needs and Teachers’ CEFR-Informed Practices.

With respect to the “how”, the learner-identified preferred ways of developing their sociolinguistic competence and the students’ preferred instructional approach, resources, and methods focus on a call for increased class time spent on oral production using authentic materials and for additional opportunities for real-world use of the language. These preferred means appear to match remarkably well with the teachers’ reported new instructional practices, which include the prioritizing of speaking, making use of guided conversations, and drawing on authentic materials and authentic action-oriented tasks, including role-plays of real-world interactions. As such, the students and teachers are both focused on developing conversational skills by engaging in guided class discussions, using authentic materials, and completing communicative tasks set in a variety of contexts with a variety of real-life, everyday, authentic purposes.

This substantial extent of “fit” between the learners’ self-identified sociolinguistic needs and the teachers’ focus on sociolinguistic competence in their self-reported CEFR-informed approach to teaching is not surprising. This is because one of the central aims of the CEFR is to make sure that L2 teaching leads students to transition successfully from L2 learners into autonomous L2 speakers as “social agents”, which makes the framework well positioned to help learners develop their sociolinguistic competence.

5. Discussion

As we have seen, only half of the FSL learners in the present study reported having developed both the sociolinguistic ability to express their own identity and intentions, and perceive the identity and intentions of other French speakers. Nevertheless, their interview responses revealed that they have developed sufficient sociolinguistic awareness to accurately assess their sociolinguistic competence. Their comments pertaining to the gaps they perceive specifically in their knowledge of sociolinguistic variants further suggest that they are aware of the full range of sociolinguistic registers available in French—and such awareness is a necessary prerequisite for the development of receptive and productive knowledge of sociolinguistic variation [8]. In addition, the students’ identification of gaps regarding their knowledge of the upper and lower register markers (i.e., hyper-formal and vernacular sociolinguistic variants) is accurate in that it matches the patterns documented in their productive use of sociolinguistic variants, which featured the use primarily of formal and, to a lesser extent, informal sociolinguistic variants. This overuse of formal sociolinguistic variants is reminiscent of the findings of past studies [9] and may well reflect their educational input, their L2 sociolinguistic goals or overall L2-related goals, or other factors [6,7]. Regarding the learners’ identification of what is missing in order for them to develop sociolinguistic competence, it is interesting to note that their calls for increased exposure to (authentic) use of French match the findings of previous research that has found it to be an effective way to develop such competence [10,11,12,17]. This finding suggests that learners have a good idea of what it is they need to learn and how to do it successfully.

The FSL teachers’ self-reported re-oriented planning, teaching, and assessment and evaluation practices provide evidence that CEFR-related professional development opportunities are an effective way for FSL teachers to become familiar with the framework and adopt its approach in their teaching, as has been suggested in previous research [25]. The teachers made it clear that their instructional practices have changed to reflect the CEFR-inspired call for being attentive to the learners’ needs. Their practices have also changed to reflect their new focus on teaching learners not about the language, but how to use the language—no longer only in terms of linguistic accuracy (i.e., vocabulary and grammar), but also in sociolinguistically and pragmatically appropriate ways. The teachers reported that this new approach is reflected in their focus on authentic and interactive activities, their increased use of authentic materials, and their increased attention to speaking skills. Importantly, the use of authentic instructional materials [32], paired with explicit instruction, including a conceptual understanding of sociolinguistic variation (which allows learners to make situation-specific decisions in relation to various contextual factors rather than follow rigid rules), has not only been proposed but also found to be an effective way to help learners develop sociolinguistic competence [19,29].

Analysis of the FSL learners’ self-reported sociolinguistic needs and the FSL teachers’ self-reported CEFR-informed instructional practices in the present study revealed a substantial amount of overlap. This overlap was in terms of content (i.e., what the learners report they need in order to develop their sociolinguistic competence and what the teachers report as their instructional focus) and method (i.e., how the learners would prefer to acquire their sociolinguistic knowledge, abilities, and skills, and the types of materials, activities, and tasks that the teachers report prioritizing). An obvious limitation of this study, however, is that it relies on the self-reports of a group of highly motivated teachers rather than on direct observations of their instructional practices or the instructional practices of teachers who have yet to embrace this new framework. As such, the data from the teachers may be best understood as a reflection of their intentions to change rather than actual changes to their practices as a result of the CEFR-informed professional learning. However, the dedication of the teachers in this study to adopt the CEFR’s new approach to teaching students the ability to communicate in socially appropriate ways in a variety of contexts appears to be strong. Because the framework envisions language teaching as leading learners to become confident, legitimate, and autonomous speakers of the target language, the development of sociolinguistic competence is both its implicit and explicit aim. If the teachers act on their intentions to focus on their students’ development of sociolinguistic competence through the use of action-oriented, real-life-based, authentic tasks and instructional materials, alongside explicit instruction on sociolinguistic variation, then the teachers’ ongoing intensive and extensive CEFR-informed professional learning is well positioned to help teachers meet the sociolinguistic needs of Ontario’s FSL students.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.R. and I.L.; writing—original draft preparation, I.L. and K.R.; writing—review and editing, K.R. and I.L.; funding acquisition, K.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) (for student data) and by the Ontario Ministry of Education and l’Association canadienne des professionnels de l’immersion (ACPI) (for teacher data).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the University of Toronto’s policies on Research Ethics for studies involving human participants.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data from this study is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- van Compernolle, R.A.; Williams, L. Reconceptualizing Sociolinguistic Competence as Mediated Action: Identity, Meaning-Making, Agency. Mod. Lang. J. 2012, 96, 234–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasan, I.; Rehner, K. Expressing and perceiving identity and intentions in a second language: A preliminary exploratory study of the effect of (extra)curricular contact on sociolinguistic development. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 2018, 21, 632–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canale, M.; Swain, M. Theoretical bases of communicative approaches to second language teaching and testing. Appl. Linguist. 1980, 1, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe Common European Framework of Reference: Learning, Teaching, Assessment. Companion Volume. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/common-european-framework-of-reference-for-languages-learning-teaching/16809ea0d4 (accessed on 18 September 2022).

- van Compernolle, R.A. Constructing a Second Language Sociolinguistic Repertoire: A Sociocultural Usage-based Perspective. Appl. Linguist. 2019, 40, 871–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Compernolle, R.A.; Williams, L. Metalinguistic explanations and self-reports as triangulation data for interpreting second language sociolinguistic performance. Int. J. Appl. Linguist. 2011, 21, 26–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Rehner, K. Learner beliefs about sociolinguistic competence: A qualitative case study of four university second language learners. Lang. Learn. High. Educ. 2015, 5, 157–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaulieu, S.; Woll, N.; French, L.M.; Duchemin, M. Language learners’ metasociolinguistic reflections: A window into developing sociolinguistic repertoires. System 2018, 76, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mougeon, R.; Nadasdi, T.; Rehner, K. The Sociolinguistic Competence of Immersion Students; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blondeau, H.; Lemée, I. Future Temporal Reference in L2 French Spoken in the Laurentian Region: Contrasting Naturalistic and Instructed Context. Can. Mod. Lang. Rev. 2020, 76, 70–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, B. Aspects of interrogative use in near-native French: Form, function, and register. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism. Linguist. Approaches Biling. 2016, 6, 467–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, B. Negation in Near-Native French: Variation and Sociolinguistic Competence. Lang. Learn. 2016, 67, 141–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regan, V.; Howard, M.; Lemée, I. The Acquisition of Sociolinguistic Competence in a Study Abroad Context; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, L.M.; Beaulieu, S. Effects of sociolinguistic awareness on French L2 learners’ planned and unplanned oral production of stylistic variation. Lang. Aware. 2016, 25, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mougeon, F.; Rehner, K. Engagement portraits and (socio)linguistic performance: A transversal and longitudinal study of advanced L2 learners. Stud. Second. Lang. Acquis. 2015, 37, 425–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruivivar, J. Best Grad Competition: Engagement, Social Networks, and the Sociolinguistic Performance of Quebec French Learners. Can. Mod. Lang. Rev. 2020, 76, 243–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehner, K.; Mougeon, R.; Mougeon, F. Variation in choice of prepositions with place names on the French L1–L2 continuum in Ontario, Canada. In Variation in Second and Heritage Languages; Bailey, R., Preston, D., Li, X., Eds.; John Benjamins: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 223–252. [Google Scholar]

- Nadasdi, T.; Vickerman, A. Opening up to Native Speaker Norms: The Use of/I/in the Speech of Canadian French Immersion Students. Can. J. Appl. Linguist. 2017, 20, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Compernolle, R.A.; Williams, L. The effect of instruction on language learners’ sociolinguistic awareness: An empirical study with pedagogical implications. System 2013, 41, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, M. The Advanced Learner’s Sociolinguistic Profile: On Issues of Individual Differences, Second Language Exposure Conditions, and Type of Sociolinguistic Variable. Mod. Lang. J. 2012, 96, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnott, S.; Brogden, L.M.; Faez, F.; Péguret, M.; Piccardo, E.; Rehner, K.; Taylor, S.K.; Wernicke, M. The common European framework of reference (CEFR) in Canada: A research agenda. Can. J. Appl. Linguist. 2017, 20, 31–54. [Google Scholar]

- Vandergrift, L. Nouvelles Perspectives Canadiennes: Proposition d’un Cadre Commun de Référence Pour Les Langues Pour le Canada; Patrimoine Canadien: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2006; Available online: https://www.caslt.org/pdf/Proposition_cadre%20commun_reference_langues_pour_le_Canada_PDF_Internet_f.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2022).

- Ontario Ministry of Education. A Framework for French as a Second Language in Ontario Schools: Kindergarten to Grade 12; Ontario Ministry of Education: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Faez, F.; Majhanovich, S.; Taylor, S.K.; Smith, M.; Crowley, K. The power of “Can Do” statements: Teachers’ perceptions of CEFR-informed instruction in French as a second language classrooms in Ontario. Can. J. Appl. Linguist. 2011, 14, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kristmanson, P.; Lafargue, C.; Culligan, K. From action to insight: A professional learning community’s experiences with the European Language Portfolio. Can. J. Appl. Linguist. 2011, 14, 53–67. [Google Scholar]

- Rehner, K. French as a Second Language (FSL) Student Proficiency and Confidence Pilot Project 2013–2014: A Report of Findings; Ontario Ministry of Education and Curriculum Services Canada: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Vandergrift, L. The DELF in Canada: Perceptions of Students, Teachers, and Parents. Can. Mod. Lang. Rev. 2015, 71, 52–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristmanson, P.; Lafargue, C.; Culligan, K. Experiences with autonomy: Learners’ voices on language learning. Can. Mod. Lang. Rev./La Rev. Can. Des Lang. Vivantes 2013, 69, 462–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, L.M.; Beaulieu, S. Can beginner L2 learners handle explicit instruction about language variation? A proof-of-concept study of French negation. Lang. Aware. 2020, 29, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Compernolle, R.A.; Williams, L. Teaching, Learning, and Developing L2 French Sociolinguistic Competence: A Sociocultural Perspective. Appl. Linguist. 2012, 33, 184–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Compernolle, R.A. Concept appropriation and the emergence of L2 sociostylistic variation. Lang. Teach. Res. 2013, 17, 343–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stigers, E. Television Subtitles for Stylistic Awareness: Developing and Implementing Media-Based Classroom Activities. Fr. Rev. 2021, 95, 19–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).