Abstract

In this study, we aimed to determine Cypriot primary mathematics teachers’ perspectives and lived experiences during the transition to emergency remote teaching (ERT) in the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic. An in-depth online survey combining closed-ended and open-ended questions was administered to sixty-two (n = 62) educators teaching mathematics in public primary schools during the first lockdown in spring, 2020. The data from closed-ended questions were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics, whereas, for the open-ended questions, a thematic analysis approach was employed. Our findings provide useful insights regarding teachers’ self-reported technology backgrounds and levels of instruction regarding the use of technology in mathematics prior to the pandemic, as well their level of preparedness for ERT and the main challenges they faced in implementing ERT of mathematics. Our findings also indicate teachers’ levels of satisfaction with their ERT practices and their beliefs concerning the extent of achievement of the curriculum learning objectives through ERT, and how these varied based on teachers’ self-reported levels of familiarity with technology, their self-reported levels of preparedness for teaching at a distance, and their engagement (or non-engagement) in synchronous instruction during ERT. Teachers’ suggestions, based on their experiences from the lockdown period, regarding how to transform mathematics teaching and learning in the post-COVID-19 era are also presented.

1. Introduction

The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic affected education on a global scale, leading to unprecedented scenarios that required expeditious responses [1,2]. The harsh restrictions and lockdowns imposed in most parts of the world led to massive school closures, forcing educational institutions at all levels to make a sudden and radical transition from face-to-face teaching and learning modes to teaching and learning at a distance [3,4]. This temporary shift in instructional delivery to an online mode due to the pandemic crisis circumstances [5], which came to be known as emergency remote teaching (ERT), posed profound challenges for teachers worldwide. Educators had to make drastic changes to their teaching practices, relying on learning management systems (LMS) and other digital tools and technologies to conduct lessons and other educational activities from home and to connect with their students [2]. They had to swiftly equip themselves with the digital competences required to cope with this new mode of delivery, with which the majority had no prior experience [6,7].

Research conducted in the early stages of the pandemic indicated that educational systems around the world were not adequately prepared to deal with the rapid changes in teaching methods imposed by ERT [4,8,9,10]. Teachers, in particular, faced numerous obstacles in adapting to teaching at a distance, both in maintaining a minimum level of communication with students to adequately support and monitor their learning progress and in achieving their instructional goals [11,12,13,14]. A significant challenge that has emerged in the international literature concerns educators’ limited skills in the use of digital technologies to support ERT. Teachers reported not being ready for the distance education process, expressing the need for training and support for them to be able to design and provide meaningful but socially distant learning experiences [15,16,17,18,19,20]. Students’ limited technical skills and inequitable access to digital devices and the internet were also major barriers reported by teachers internationally [8,9,21,22]. Teachers also reported difficulties due to non-reliable internet access and/or a lack of infrastructure [20]. However, despite their difficulties in shifting from face-to-face teaching to ERT, educators not only highlighted challenges but also identified positive aspects and opportunities emerging from the pandemic [11,23], such as the possibility to interact with students even in a period of emergency [17], to create meaningful and engaging lessons using innovative technologies [17,18,19,24], and to foster students’ digital literacy skills and other key 21st century competences that were previously difficult to cultivate [2].

In Cyprus, similarly to the rest of the world, the first lockdown due to COVID-19 in March 2020 was sudden and unexpected, thus disrupting the normal operation of various services across the country. Education was severely affected since schools, educational authorities, teachers, and students were unprepared to operate under the challenging conditions imposed by the closure of schools and the transition to synchronous and/or asynchronous digital teaching and learning methods at all levels of education [25,26]. This transition was particularly challenging for teachers in the public sector, who, unlike their colleagues working in private schools, had not been offered any training in teaching at a distance prior to the lockdown, and also had to face a number of policy, human resources, and infrastructure constraints [25,27,28,29].

In the current study, we focused on Cypriot primary teachers’ self-reported experiences and practices in the teaching of mathematics during the transition to ERT. The focus on mathematics education stemmed from the fact that mathematics is one of the disciplines that has been particularly challenged by the ‘new normal’ in education imposed by the pandemic, possibly due to the subject’s symbolic nature and its emphasis on paper rather than technology [30,31]. The COVID-19 pandemic has posed multiple practical and pedagogical challenges for mathematics educators [21,32], and has led to an unprecedented call for them to re-envision mathematics instruction so as to sustain effective learning in the virtual space [33]. Mathematics teachers have been called upon to transform the objectives of their lessons and to adapt their teaching practices to the new conditions by choosing appropriate digital tools, teaching techniques, and mathematical activities [2]. However, despite educators’ efforts to devise effective practical approaches and strategies for establishing mathematical dialogue in their ERT and for supporting students in developing their mathematical thinking and reasoning, uncomfortable facts and figures related to mathematics teaching and learning during the pandemic have surfaced [30]. For example, teachers participating in a study carried out in 2020 by the Joint Mathematical Council of the UK (JMC) and the Royal Society Advisory Committee on Mathematics Education (RS ACME) to investigate the effects of COVID-19 on the teaching and learning of mathematics for 3–19-year olds in primary and secondary schools and colleges in the UK identified a negative impact of the pandemic on students’ engagement with mathematics and motivation for learning [34]. Teachers also indicated that students’ lack of engagement and motivation were more detrimental to the learning of mathematics than the lack of access to digital technology, and that they had to change what they taught in response to the pandemic. They also reported that more than half of their students were three months or more behind their learning of mathematics compared to what could have been achieved in a face-to-face teaching process.

Although the international research literature examining educational institutions’ transitions to ERT is extensive and provides in-depth analysis of teachers’ and students’ challenges and experiences [17], few studies have focused on mathematics teachers. Research targeting mathematics teachers at the primary school level in particular is scarce. As a result, very little is currently known about primary mathematics teachers’ experiences and perceptions of ERT, or about the ways in which they taught mathematics during ERT [31]. In Cyprus, although some research evidence about the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on school education in Cyprus does exist [25,27,28,29], no prior study has focused on mathematics education.

In this survey study, we aimed to contribute to the national and international mathematics education research literature by investigating the perspectives, lived experiences, and self-reported practices of primary school mathematics teachers in Cyprus during their transition to ERT in Spring 2020. The following research questions were posed to guide our inquiry:

- What were teachers’ self-reported technology backgrounds and levels of preparedness for ERT?

- Which challenges did teachers report facing during the transition from face-to-face instruction to ERT?

- What didactic strategies and digital tools did teachers report utilizing during ERT of mathematics and how did these compare to the strategies and tools they reported using prior to the pandemic?

- What were the teachers’ reflections on their ERT experiences and what were their conceptualizations of the way forward for technology-enhanced mathematics instruction in the post-COVID-19 era?

2. Literature Review

Despite our extensive searches in different search engines (Scopus, Google Scholar), we have located only a few published studies focused on mathematics teachers’ perceptions and experiences regarding ERT. These studies can be broadly divided into (a) studies that involved mathematics teachers of different educational levels, (b) studies that focused exclusively on teachers teaching mathematics at the primary level, and (c) studies that focused exclusively on secondary-level mathematics teachers. In the following section, we present our findings from the literature, following the categorization presented above.

2.1. Studies Examining ERT Perceptions and Experiences of Mathematics Teachers at Different Educational Levels

The authors in [35] explored how primary and secondary school teachers from four countries—France, Israel, Italy, and Germany—managed their teaching/learning activities within the context of the lockdown imposed by the pandemic, with a focus on mathematics education. About 700 teachers from the four countries participated in the study. The empirical analysis suggested that there were four tasks corresponding to the main challenges that teachers had to face during the lockdown: (a) managing distance learning to support students’ learning through specific methodologies, (b) managing distance learning to develop assessments, (c) managing distance learning to support students who faced difficulties and/or were living a difficult situation/developing and employing inclusive teaching practices, and (d) managing distance learning to exploit its potential for fostering typical mathematical processes. Teachers described a struggle between their willingness to carry on as before in the classroom and their disappointment in not achieving exactly what they aimed at due to the adverse working conditions (unstable networks, the poor reliability of institutional platforms, family constraints) and the impossibility of reaching all students, particularly those facing difficulties. Teachers referred to challenges and constraints in communication, interaction, collaborative learning, and assessments. Additionally, they identified the “dishonesty” of some students as an issue. At the same time, many teachers saw the pandemic as an opportunity for mathematics educators to radically change their traditional teaching methods.

Similarly to [35], the authors in [36] also focused on both the primary and secondary levels. The authors explored teachers’ perceptions of how the pandemic influenced their mathematics instruction by investigating the ways in which teachers used particular mathematical exercises and digital tools during ERT and when returning to face-to-face instruction. The study participants were 68 educators, including general education elementary teachers, special education teachers, and secondary mathematics teachers, who taught students in grades ranging from the first to the ninth grade. According to the study’s findings, when these teachers started teaching in person, the organization of their classroom was influenced by their virtual teaching of mathematics. Participants stated that during virtual mathematics teaching, they utilized apps such as Pear Deck, Seesaw, Google applications, edPuzzle, and other non-mathematics-specific digital technologies and continued to use them when they switched to in-person instruction.

The authors in [37] explored primary-school- to undergraduate-level Italian mathematics teachers’ emotions and perceptions about ERT during the first lockdown through essays. Their analysis revealed similar findings to those of [35] regarding teachers’ perceptions of feeling unprepared and struggling to adapt to the new reality. The authors defined the situation of the participating teachers as “a first period of bewilderment” [37] (p. 32). They stated that their study participants experienced “very strong emotions” due to ERT, which were interlinked with teachers’ difficulties in engaging in “normal didactic activity, with the discomfort of having to manage one’s own professional activity without feeling to have the tools to do so (that is, with a low perceived competence)” [37] (p. 32) as well as with the lack of being physically present for their students.

2.2. Studies Focused on Primary School Mathematics Teachers’ ERT Perceptions and Experiences

We only located three studies that focused exclusively on primary school teachers’ perceptions, experiences, and practices regarding ERT of mathematics—one conducted in Australia [38], one in the US [39], and one in South Africa [40].

The authors of the study conducted in Australian primary schools [38] aimed to understand how teachers planned and implemented mathematics learning programs for their students during the school lockdown, the challenges they encountered, as well as the extent to which their students were motivated or engaged when learning mathematics at home. During the interviews, teachers described aspects of setting up and delivering the remote teaching of mathematics that were challenging for themselves or their school community. The teachers referred to several technology challenges for students, their families, and teachers and to the lack of real-time feedback. At the same time, the study findings indicated that teachers made considerable effort to effectively cater for all students and to assess student progress and engagement with the tasks. The survey data revealed that most students displayed positive engagement with remote learning experiences, despite the lack of opportunities to learn mathematics with and from their peers.

A large-scale study [39] was contacted in the US to understand and describe how the COVID-19 pandemic affected the delivery of instruction. Two surveys were sent to a sample of over 9000 primary teachers who were randomly selected to be representative of the population in the US. The purpose of the first survey was to examine the academic instructional opportunities in reading, writing, and mathematics provided to elementary school students during school closures in the spring 2020 semester due to the pandemic. The purpose of the second survey was to understand the nature of instruction provided, and teachers’ perceptions of the effectiveness of instruction and student achievement during the fall 2020 semester, when schools reopened. The results indicated that many students did not receive direct instruction in academic skills during the spring 2020 semester. Although by late fall of 2020 teachers reported the broad use of some form of in-person instructional model, they indicated that many of their students were not ready to transition to the next grade level and that achievement gaps in mathematics were larger in fall 2020 than in typical years.

The study conducted in South Africa [40] used two questionnaires focusing on strategies for supporting mathematics learning in primary education. The research and data analysis were based on the activity theory framework. The authors found that there were differences in the ways of utilizing technology between poorer and wealthier schools, which is in alignment with the differences between public and private schools in Cyprus, as discussed in the introduction of this paper [25]. The results of the study indicated that teachers were mainly utilizing the WhatsApp application (a free internet-based messaging service) for administering assignments and homework. Additionally, the authors found that in more affluent schools, teachers were also using Microsoft Teams and Zoom for synchronous sessions with their students, YouTube for providing them with the opportunity to watch explanatory videos asynchronously, and Facebook for sharing resources and information asynchronously. The authors of this study also reported, as did those of [35], that teachers and their students (as well as parents) faced challenges in the transition to ERT. As one participant mentioned, “Parents, learners, and teachers were very afraid…it was difficult to get learners, teachers and parents motivated…learners who are struggling with no support from home are struggling more” [40] (p. 8).

2.3. Studies Focused on Secondary School Mathematics Teachers’ ERT Perceptions and Experiences

Compared to studies of the primary level, a larger number of studies explored secondary mathematics teachers’ perceptions, experiences, and practices regarding ERT. Specifically, we located studies conducted in Belgium, Germany and the Netherlands [41], Spain [42], England [43], South Africa [1], Indonesia [44,45] and Saudi Arabia [46].

The authors in [41] researched mathematics ERT in Belgium, Germany, and the Netherlands. According to the study’s findings, the number of mathematics-specific tools utilized by educators prior to the lockdown significantly decreased during ERT. Throughout the lockdown, teachers’ confidence in using digital technology improved. Their beliefs regarding mathematical education and the role of digital technology in this area, as well as their confidence in and experience with using digital technology in their teaching, played a role in their engagement in ERT, but to a lesser extent than expected. Moreover, the authors had hypothesized that teachers would prioritize lower-order learning goals such as rote memorization and drill over higher-order learning objectives such as conceptualization and the exploration of new mathematical concepts. However, teachers reported focusing on rehearsal and conceptual comprehension and introducing new material. This appears to contrast with the findings of the study by Rodriguez conducted in Spain [42]. The authors in [42] analyzed the perceptions of secondary mathematics teachers regarding their readiness for ERT during the pandemic, based on their technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK), their previous training in digital teaching tools, their level of digital competence for the teaching of mathematics, and their adaptation to ERT. Their findings revealed that the sudden transition to ERT forced teachers to slow down the pace of teaching and to reduce the amount of content taught. Additionally, significant differences were observed based on gender and age with respect to teachers’ perceptions of their adaptation to ERT. Furthermore, despite the positive influence of previous training on their perception of readiness for ERT, in general, teachers recognized their need for further training.

The findings of a report published in September of 2020 by the UCL Institute of Education [43] indicated that schools and mathematics departments in England broadly chose one of three options for their remote teaching: continuing to follow their existing mathematics curriculum as planned, following it at a slower pace and/or with reduced content, or aiming to review and consolidate previous learning. Additionally, participation was unequal. Students with low prior attainment and other disadvantaged learners were found to be participating less and, when they did participate, they were less engaged. Furthermore, the lockdown restricted the opportunity to learn mathematics for most students; low attainers and other disadvantaged students faced greater constraints. These constraints included a reduction in the scaffolding or additional adult support available to low prior attainers and a more limited range of task types. Only a small minority of students experienced unexpected benefits. The lockdown provided very limited opportunities for students to engage in mathematical talk and metacognitive activities or to receive formative feedback. A major disadvantage of the ERT practices employed were the lack of opportunities for students to interact with teachers and with each other. Almost none of the schools participating in the study facilitated live interactions between students, with many citing safeguarding concerns rather than technical and pedagogical issues.

The authors in [44] investigated Indonesian secondary mathematics teachers’ perspectives on the application of ERT during COVID-19. According to the researchers, Indonesian teachers encountered several challenges in adapting to ERT. Their students also lacked e-learning knowledge and abilities, and many also lacked access to devices and an internet connection. The authors in [45], who also investigated Indonesian secondary mathematics teachers’ perceptions of ERT, obtained similar results regarding teachers’ low levels of readiness for implementing ERT and particularly for utilizing subject-specific applications in mathematics instruction, as well as concerning students’ difficulties in accessing infrastructure and the internet. On the positive side, teachers in [45] argued that ERT encouraged them and their students to become more competent users of digital technologies.

The practice of ERT due to COVID-19 and the teaching and learning of mathematics in South Africa were examined in the context of historical disadvantage [1]. The study employed a sample of 23 mathematics instructors teaching grade 12 at several public secondary schools in South Africa. The research revealed how ERT forced mathematics teachers to become lifelong learners as they adapted to digital teaching, solved new difficulties, and acquired knowledge from a broader global mathematics education community, which was in alignment with the findings of [46] in Saudi Arabia. In that study, 120 secondary mathematics teachers in Saudi Arabia were interviewed by a researcher. Almost all participants reported a great expansion in the use of various tools and technologies in mathematics during ERT to facilitate online communication between teachers and students and the more effective learning of mathematical concepts. These included mobile devices, digital libraries, designing learning objects in mathematics education, massive open online courses (MOOCs) in mathematics, and computer algebra systems (CASs) (e.g., Mathematica, Maple, and Maxima). Teachers’ responses indicated that they indeed saw the pandemic as a gateway for digital learning in mathematics education, and that they intended to continue using digital technology in mathematical education after the end of the pandemic, similarly to the findings from [36], recognizing that students’ access to mobile devices and other technological tools allowed them to learn at their own pace and according to their own learning style.

As can been seen from the literature review, the majority of studies investigating mathematics teachers’ perceptions, experiences, and practices regarding ERT have focused on secondary education, whereas research focusing exclusively on primary mathematics teachers is very scarce. This gap was also noted in [40,47]. In our research, we aimed to contribute towards filling this gap by exploring Cypriot primary teachers’ perspectives, lived experiences, and self-reported practices during the transition to ERT in the early stages of the pandemic.

3. Methodology

3.1. Instruments, Data Collection, and Analysis Procedures

A survey instrument was designed based on the previous survey studies conducted by the authors [25,48], as well as survey studies targeting students or teachers that were published in the early stages of the pandemic [49,50,51,52]. Most of the questions were closed-ended, requesting Likert-type ratings or multiple-choice responses. A few open-ended questions requiring text-based responses were also included to obtain more comprehensive information.

The survey instrument was developed in Greek. It was pilot-tested with five (n = 5) teachers (who were then excluded from the sample), who completed the survey and also offered extensive feedback on their experience of filling it out and suggestions for improvement (e.g., changes in the wording of some questions, the deletion of questions, etc.). After being revised based upon the feedback received, the survey was posted electronically via Google Forms.

The finalized version of the questionnaire contained 8 sections, with 59 questions overall (46 closed-ended questions and 13 open-ended questions). The sections were as follows: (i) Demographics (6 questions); (ii) Technological Background and Extent of Usage Prior to the Pandemic (6 questions); (iii) Level of Preparedness for Teaching at a Distance (4 questions); (iv) Use of Technology during ERT (11 questions); (v) Synchronous ERT Practices (7 questions); (vi) Reflection on Synchronous ERT Practices (9 questions); (vii) Reflection on Asynchronous ERT Practices (9 questions); (viii) Reflection on Challenges and Opportunities Emerging from the Implementation of ERT (7 questions). The instrument’s reliability was checked with the Cronbach alpha (a > 0.7). The survey took about 20–25 min to complete.

Inspired by Puentedura’s Substitution, Augmentation, Modification, and Redefinition (SAMR) model [53], the questions asking teachers about didactic strategies and the use of digital tools prior to and during the pandemic aimed at investigating whether technology was used in creative ways that fostered a deep understanding and engagement through higher-order thinking and socio-constructivist-style activities, or whether it was merely used as an “add-on” to existing teaching and learning activities.

After obtaining the approval of the Cyprus Centre of Educational Research and Evaluation, an invitation explaining the purpose of the study and providing a link to the teacher survey was sent via email to the Cypriot primary school teachers’ trade union, with a request to distribute the survey to all its members. Social media was also used to disseminate the survey instrument. The data collection process lasted between July and August, 2020. Participation was completely voluntary and anonymous. No identifying information was collected from participants.

A total of 108 educators teaching in public primary schools in Cyprus (ages 6–12) responded to the survey. Sixty-two (n = 62) of the respondents indicated that mathematics was among the subject(s) they had taught during the 2019–2020 school year (and thus during the emergency remote education period that followed the first lockdown in Cyprus in March 2020). Given that the current study was focused on mathematics teachers’ practices during ERT, we restricted our analysis to the responses of these 62 teachers. All of these teachers (n = 62) responded to all of the closed-ended questions, since responses to closed-ended questions were mandatory. The majority also provided answers to the open-ended questions despite these questions being optional. The percentage responding to each open-ended question ranged between 60% (n = 38, 61.3%) and 90% (n = 56, 90.3%). Quantitative data obtained from the survey closed-ended questions were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics (the SPPS 24 package was used). The analysis of the qualitative data obtained from the open-ended questions followed a qualitative thematic analysis approach [54,55], during which data were coded and clustered into themes. The combination of quantitative and qualitative data provided complementary information and a more holistic picture of teachers’ experiences and perceptions regarding the transition from face-to-face teaching to ERT.

3.2. Participants’ Demographic Characteristics

Table 1 summarizes some demographic information and background characteristics of the study participants.

Table 1.

Demographics and other characteristics of the teachers participating in the survey.

As shown in Table 1, four fifths of the teachers (n = 50; 80.6%) were female. Participants tended to have many years of teaching experience (n = 51, 82.2% more than 15 years) and thus to belonged to older age cohorts (only 33.9% were younger than 40). The survey respondents represented the complete range of primary teachers in Cyprus fairly well in terms of gender and years of experience. According to Eurostat [56], 90% of primary school teachers in Cyprus during the 2019–2020 school year were females, whereas 86% were older than 35 years.

In Cyprus, all primary teachers need to have a bachelor’s degree in Education Sciences, but most teachers have higher academic qualifications. This is reflected in the current study, in which around 90% the respondents (n = 55, 88.7%) had at least a master’s degree, with 5 of the participants (8.1%) also holding a doctoral degree.

4. Results

The findings have been organized into the following four sections:

- Teachers’ technological backgrounds and levels of preparedness for ER;

- Transition to ERT and technologies used;

- Challenges during the transition to ERT; and

- Reflection on the ERT experience.

4.1. Technological Backgrounds and Levels of Preparedness for ERT

Teachers were asked to indicate their level of familiarity with ICT. As shown in Table 2, only one teacher rated himself/herself as a beginner. Half of the respondents rated their familiarity level either at the advanced (n = 26, 41.9%) or at the expert level (n = 5, 8.1%). At the same time, the other half (n = 30, 48.4%) considered themselves to be at an intermediate level, which suggests that a sizable proportion of the participants were experienced with technology but lacked relative sophistication.

Table 2.

Technological backgrounds of the teachers participating in the survey.

In a question prompting participants about their attitudes towards the use of new technologies in their daily and/or professional life, more than 40% indicated either that they loved new technologies and were always among the first to experiment with them (n = 7, 11.3%), or that they liked them and tended to use them before most people in their circle would (n = 20, 32.3%). At the same time, more than half noted either that they were cautious towards new technologies and only used them when necessary (n = 10, 16.1%), or that they usually decided to use a new tool when most people they knew of were already using it (n = 24, 38.7%).

All participants indicated having access to the internet at home and owning their own PC/laptop. The majority also owned a smartphone (n = 57, 91.9%) and/or a tablet (n = 44, 71.0%).

Respondents’ technology usage patterns before the COVID-19 pandemic were measured by providing them with a list of technological tools/technologies and asking them to indicate, using a 5-level Likert scale (5 = Daily, 4 = Weekly, 3 = Monthly, 2 = Rarely, 1 = Never), the frequency with which they used each tool either personally or for professional development purposes (not for teaching). Table 3 shows, in descending order, the number/percentage of teachers that reported using each tool/technology on a daily or weekly basis.

Table 3.

Number/percentage of teachers who reported employing each tool “daily” or “weekly” either personally or for professional development purposes (not teaching) before the pandemic.

As shown in Table 3, large majorities of the teachers reported employing in their daily and/or professional lives the following tools on a daily or at least weekly basis: instant messaging (n = 59, 95.5%), email (n = 57, 91.1%), smartphones (n = 55, 88.7%), laptops/PCs (n = 53, 83.9%), and social media such as Facebook and Instagram (n = 53, 85.9%). Around half reported regularly using cloud and file sharing platforms such as Dropbox and Google Drive (n = 30, 48.4%) and tablets (n = 30, 48.4%). Smaller but sizeable percentages reported making frequent use of media sharing sites such as YouTube and Vimeo (n = 24, 38.7%), online forums (n = 21, 33.9%), e-books/e-readers (n = 18, 29.0%), communication and collaboration tools such as blogs and Google Docs (n = 16, 25.8%), and supportive technologies such as screen magnifiers (25.8%).

It can therefore be concluded that most of the participating teachers extensively used both mobile devices and laptops/PCs in their daily and/or professional lives, whereas a significant proportion made active use of communication and collaboration tools, as well as e-books/e-readers and supportive technologies. By contrast, the vast majority infrequently or never used technologies such as e-portfolios; massive open online courses (MOOCs); multimedia editing software (e.g., Movie Maker, iMovie, Final Cut, Premiere); or simulations, gaming, or virtual worlds.

Participants were also asked to indicate, again using a 5-level Likert scale (5 = Daily, 4 = Weekly, 3 = Monthly, 2 = Rarely, 1 = Never), the frequency with which they used each of 23 different technological tools in their teaching. Three of the listed tools referred to software designed specifically for mathematics education: mathematics education applets, dynamic geometry software, and other software designed for mathematics education. Table 4 shows the percentages of teachers who indicated using each tool on a daily or weekly basis.

Table 4.

Number/percentage of teachers reporting incorporating each technology/technological tool into their teaching on a “daily” or “weekly” basis prior to COVID-19.

Teachers participating in this study indicated that they had been incorporating various technological tools into their teaching prior to the pandemic. PowerPoint presentations were the most popular technological tool, with almost everyone (n = 57, 91.9%) reporting having used PowerPoint presentations on a daily/weekly basis before the pandemic. Videos were also regularly used by a large majority (n = 45, 72.6%). The majority of teachers also frequently used interactive applets (n = 40, 64.5%) and/or other educational software designed for teaching a specific subject (n = 32, 51.6%). In their mathematics lessons, around 70% (n = 44, 71.1%) reported regularly using mathematics education applets, and around 60% (n = 36, 58.1%) reported using other software designed for mathematics education. Software supporting dynamic geometry such as Geometer’s Sketchpad were employed much less frequently—only 29% often used such software.

With the exception of cloud and file sharing platforms and eBooks, which were frequently used for instructional purposes by more than 40% of the respondents, the percentages reporting the daily/weekly use of each of the remaining tools listed in Table 4 prior to the pandemic were low (9.7%–21.0%). Only a small number of teachers had, prior to the lockdown, been using e-learning tools such as online/electronic quizzes, podcasts/audio files, chats, discussion forums, breakout rooms, and online homework. The vast majority also made low use of interactive tools such as simulations, gaming, virtual worlds, electronic voting systems, programming software, and media manipulation software, which can promote student motivation and active participation in mathematics and other subjects. Special software for better accessibility (e.g., screen magnifiers, screen readers, etc.) were used by around one fifth of the educators (n = 13, 21.0%).

Most of the teachers had not participated in any distance learning programs as either trainees (n = 44, 71.0%) or trainers (n = 58, 93.5%), nor had they participated in any training related to distance education (n = 52, 83.9%) (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Participants’ prior backgrounds in distance education and self-reported levels of preparedness for ERT.

The most common reason teachers gave for not having participated in any training in distance learning prior to the pandemic was that they had never been given the opportunity to do so (n = 39, 62.9%). Ten participants (16.1%) stated that they had not participated in any training related to distance learning due to a lack of personal interest, and three other participants attributed it to a lack of time (4.8%).

Table 5 also presents results regarding teachers’ responses to the following question: “How prepared do you think you were at the onset of the Spring 2020 lockdown to start offering synchronous online instruction?”. As seen in Table 5, about 70% (n = 44, 70.9%) of the respondents stated that they were slightly or not prepared at all to start synchronous ERT. Only eight teachers (12.9%) felt that they were well prepared.

4.2. Transition to ERT and Technologies Used

Public schools in Cyprus closed down in the middle of March of 2020. It took a significant amount of time for the Ministry of Education to react and provide guidelines for teachers on how to start teaching online. However, almost all educators took the initiative to start teaching asynchronously immediately after the schools closed by sending material to their students and by checking on their progress with parental involvement. Some also took the initiative to start synchronous ERT without waiting for the official guidelines from the Ministry of Education. The majority, however, waited for guidelines from the educational authorities to start synchronous ERT (for more details about the timeline of the transition to ERT in Cyprus during spring, 2020, see [2]).

Similarly to other Cypriot teachers, the primary school teachers participating in our study started with asynchronous ERT, with synchronous ERT following within 2–3 weeks for most of them. All respondents offered asynchronous ERT to their students, whereas three-fourths (n = 48, 77.4%) offered synchronous ERT as well.

Almost all teachers used their own equipment while teaching from home. In some cases, schools provided a laptop or a tablet to teachers to facilitate their online teaching. In rare cases, schools provided a webcam or a digitizer to teachers to make their teaching more efficient.

The most popular platform used by teachers for their synchronous sessions was MS Teams since it was the platform endorsed in the official guidelines and supported by the Ministry of Education. Since the shift to ERT took several weeks to officially start (see [25]) many teachers also experimented in the meantime with various other platforms (WebEx, Zoom, Jitsu, Skype, etc.).

Teachers also reported using additional tools to communicate asynchronously or synchronously with their students and to facilitate ERT: Viber (n = 14), ClassDojo (n = 4), email (n = 7), the school website (n = 2), phone (n = 2), and Moodle (n = 1).

Participants were asked to indicate the extent of the integration of technology during synchronous ERT, as they had done for the period prior to the onset of COVID-19. Table 6 shows the number/percentage of teachers incorporating each listed technology/technological tool into their teaching on a daily or weekly basis prior to and during lockdown.

Table 6.

Number/percentage of teachers reporting incorporating each technology/technological tool into their teaching on a “daily” or “weekly” basis prior to and during lockdown.

Unsurprisingly, there was a slight increase in the level of use of PowerPoint presentations, lectures/seminars that use screenshots and narrative presentations, asynchronous discussion forums, synchronous chats, breakout rooms, podcasts/audio files, online homework assignments, and online quizzes. Furthermore, many teachers used instant messaging and/or social media to communicate with their students, something which they did not do prior to the pandemic, possibly due to their students’ young ages. On the other hand, there was a decrease in the use of both general-purpose and subject-specific software, open-source instructional material, eTextbooks, and associated online content. The use of constructive technologies such as simulations, gaming, virtual worlds, electronic voting systems, and media manipulation software continued to occur at similarly low levels to those prior to the pandemic.

The participating teachers were using various technological tools in their mathematics instruction prior to COVID-19. Half reported using mathematics education applets daily or weekly and more than 40% reported using other software designed for mathematics education. These numbers dropped during ERT. The numerous challenges that teachers faced during ERT, which are outlined below, were probably the reason behind this drop.

4.3. Challenges during the Transition to ERT

As already noted, the majority of study participants (n = 48, 77.7%) engaged in both asynchronous and synchronous ERT. They faced various issues during the transition to synchronous ERT (see Table 7). Three-fourths (n = 37, 77.1%) felt that students’ discomfort or lack of familiarity with the required technologies was a major challenge, whereas around half (n = 25, 52.1%) considered their own discomfort and lack of familiarity with the required technologies to be a challenge. A high percentage of teachers also faced challenges related to their limited access to reliable software or communication tools (n = 23, 47.9%), to reliable internet connection (n = 21, 43.8%), and/or to a reliable digital device (n = 17, 35.4%).

Table 7.

Number/percentage of teachers for whom each technological issue was a challenge “to a high extent” or “to a very high extent” during the transition to synchronous ERT.

Students’ limited access to technology was also a challenge several participants had to face. Although 80% (n = 50, 80.6%) stated that all or almost all their students had access to asynchronous online learning, eight teachers (12.9%) indicated that only about half of their students did, and four teachers (6.4%) indicated that only a few did. Access was even more limited when it came to synchronous online learning. Only two thirds of the participants (n = 39, 62.9%) stated that all or almost all of their students had access to synchronous online learning, whereas around 30% (n = 14, 22.6%) indicated that only a few did.

Another challenge faced by teachers during the transition to synchronous ERT was students’ difficulties in adapting to emergency remote learning (ERL). In a question asking them to indicate, based on their experiences and observations as teachers, how difficult it was for their students to adapt to synchronous ERL (see Table 8), almost 60% of the teachers who had engaged in synchronous ERT agreed that their students faced several difficulties (n = 22, 45.8%) or that they found it very difficult to adapt to ERL (n = 6, 12.5%). On the other hand, one third of the teachers (n = 16, 33.3%) believed that their students faced only a few difficulties in adapting to ERL.

Table 8.

Number/percentage of respondents who had engaged in synchronous ERT who selected each response to a question asking them to describe their students’ adaptation to synchronous ERL.

Teachers’ responses to an open-ended question where they had to describe particular difficulties that arose in relation to online distance teaching and learning were in alignment with the quantitative data. Participants identified students’ and teachers’ lack of familiarity with the required technologies or applications, students’ limited access to reliable internet connection and devices, and technical issues as major challenges:

At the beginning everything was difficult for the students until they got familiarized with the procedure and the tools.

Many children did not have a reliable internet connection and only had 4G which was running out fast and it was not possible to use video or other educational media. Some students had only a telephone and synchronous online teaching was very difficult.

The Teams program was too heavy for ordinary computers so the computer became very slow and got stuck.

No preparation happened beforehand. Students didn’t have usernames, passwords. Very few teachers knew how to use TEAMS.

Students need help from their parents. If their parents could not offer help then it was impossible for students to attend the class remotely.

Unreliable internet access and devices, lack of knowledge and skills from teachers and students were issues we faced.

Applications proposed by the Ministry of Education for use in distance learning did not work or led to websites with advertisements or which required registration.

Teachers were asked to indicate, using a 5-level Likert scale (5 = Always, 4 = Often, 3 = Sometimes, 2 = Rarely, 1 = Never), how often they had experienced each of the difficulties shown in Table 9 during the Spring 2020 ERT period.

Table 9.

Number/percentage of teachers reporting “always” or “often” facing each challenge during synchronous ER.

An excessive workload was an issue frequently faced by two thirds of the teachers who engaged in both synchronous and asynchronous ERT (n = 33, 68.8%), and difficulties due to having to simultaneously manage their teaching duties along with their family needs were noted by almost half of them (n = 22, 45.8%). Internet connectivity issues were reported by more than half of these respondents (n = 26, 54.2%), and insufficient knowledge and skills regarding the use of new tools and technology were noted by 40% (n = 19, 39.6%). By contrast, only a small proportion of the teachers faced difficulties due to students’ negative attitudes or classroom management issues during the lessons. Other difficulties noted by several teachers were “noise in children’s homes, delay in children entering the class”, as well as the constraints imposed by the fact that students were not allowed to turn on their cameras (this was an official guideline from the Ministry of Education due to GDPR):

Absence of an image of the children which would help me to identify students who were confused or struggling with something. No active participation by most children and avoidance to ask questions during the lesson.

4.4. Reflection on the ERT Experience

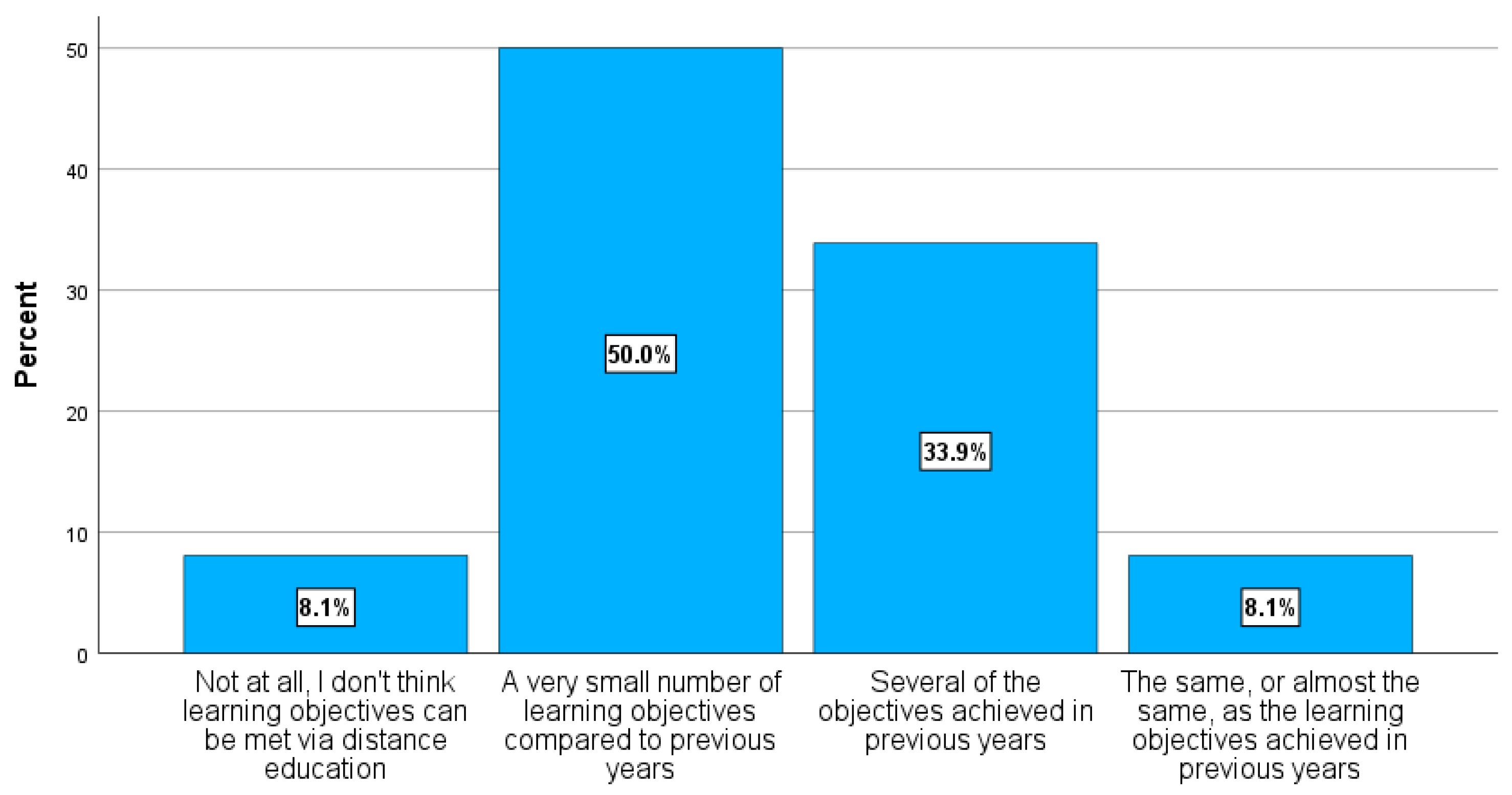

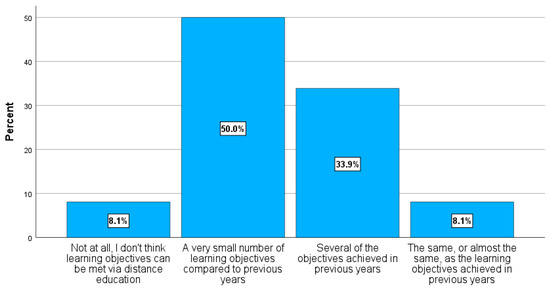

In the last section of the survey, participants were asked to respond to some reflective questions about the implementation of ERT. Figure 1 shows teachers’ responses to a question where they had to indicate the extent to which they believed the curriculum learning objectives were achieved through ERT.

Figure 1.

Extent to which teachers believed that the learning objectives of the curriculum were achieved through their ERT.

Only around 40% of the teachers felt that the same or almost the same (n = 5, 8.1%) or that several of the objectives achieved in previous years (n = 21, 33.9%) were achieved through the ERT approach. Half of the respondents (n = 31, 50.0%) felt that only a very small number of learning objectives were achieved compared to previous years, whereas five teachers (8.1%) argued that learning objectives were not achieved at all, because they did not think learning objectives can be met via distance education.

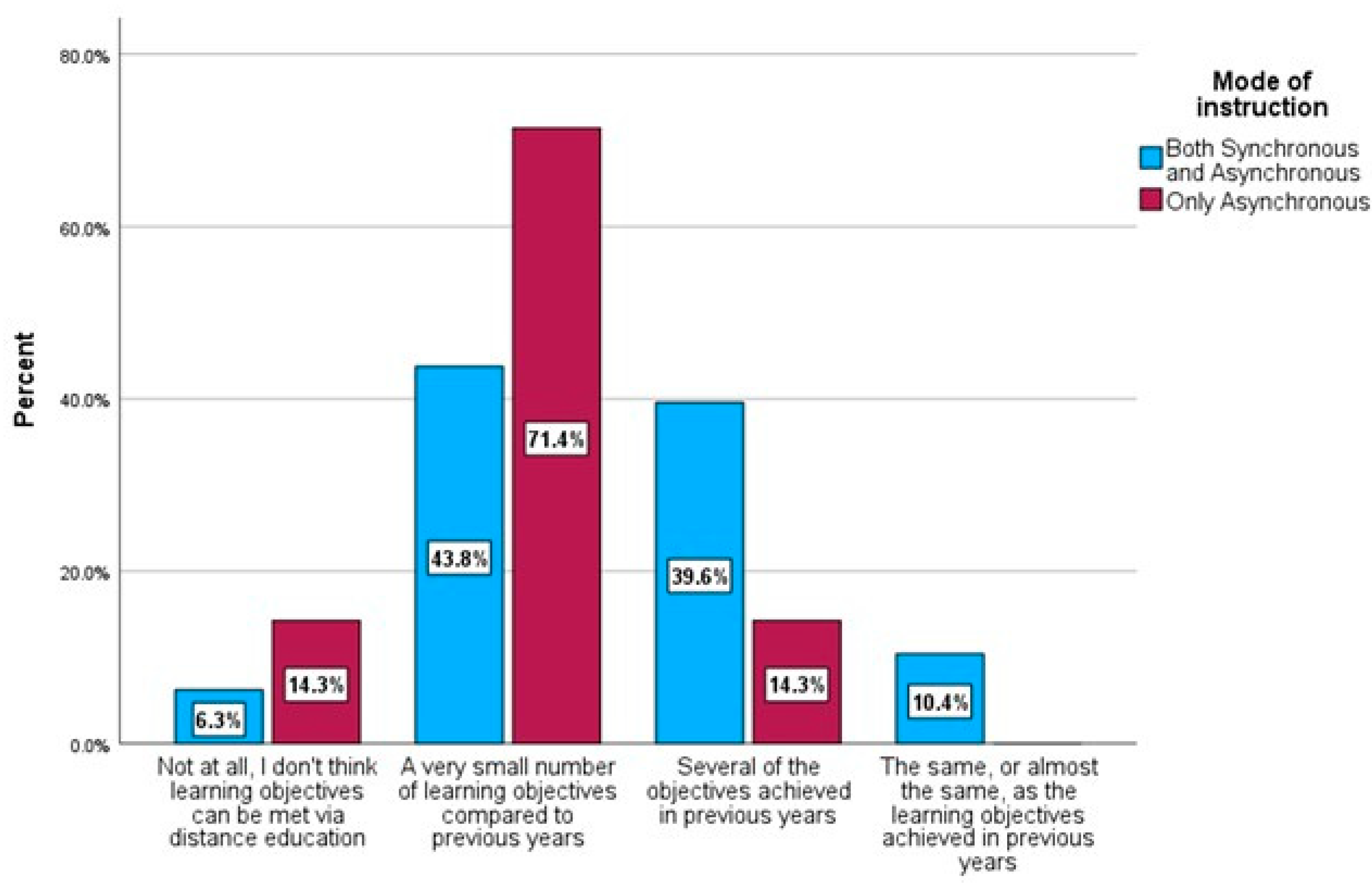

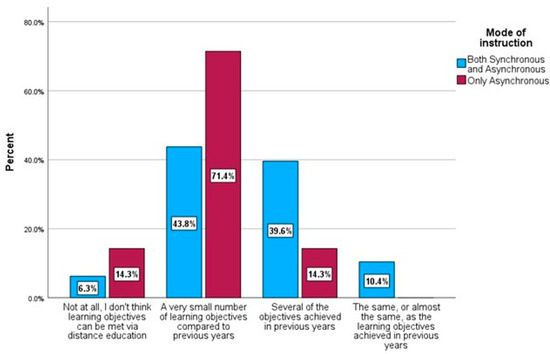

As shown in Figure 2, the extent to which teachers believed that the curriculum learning objectives were achieved through ERT varied significantly based on whether they engaged in synchronous ERT or not (U(48, 14) = 205.0, z = −2.41, p = 0.016 < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Extent to which teachers (separated based on whether they had engaged in synchronous ERT or not) believed that the curriculum learning objectives had been achieved through their ERT.

Although half (50.0%) of the participants from the group of teachers who used synchronous ERT felt that “several learning objectives” or “the same or almost the same learning objectives” were achieved compared to previous years, the corresponding percentage among teachers who engaged only in asynchronous ERT dropped to 14 percent. More than four fifths (85.7%) of the participants from the asynchronous-only group responded that very few learning objectives were achieved compared to previous years, or even that no learning objectives at all could be achieved through distance learning.

The extent to which teachers felt that the curriculum learning objectives were achieved through ERT also varied significantly based on their self-reported levels of preparedness for ERT (U(44, 18) = 244.0, z = −2.58, p = 0.01 < 0.05). Although 72% of the teachers who self-rated their preparedness for ERT as high felt that “several of the learning objectives” or “the same or almost the same” learning objectives were achieved, only 30% of those who rated their preparedness levels as low did. Similarly, although 55% of the teachers who had rated their levels of familiarity with technology at the advanced/expert level felt that “several of the learning objectives” or “the same or almost the same” learning objectives” were achieved, only 29% of those who self-rated their familiarity with technology at the beginner/intermediate level did. However, differences based on self-reported levels of familiarity with technology were not statistically significant ERT (U(31, 31) = 361.0, z = –1.84, p = 0.07 > 0.05).

Regarding mathematics instruction in particular, in their open-ended responses many teachers noted that prior to the pandemic they often used student-centred approaches such as group work, the differentiation of instruction, and the use of applets and other ICT tools to promote active participation in the lesson and to maximize learning outcomes. Shifting to ERT, they had to face several challenges especially in trying to introduce new concepts in a way that would actively engage students in the learning process. For example, one obstacle to student active participation repeatedly pointed out by teachers was the fact that students were not able to turn on their cameras. As a result, teachers were teaching in front of a screen without being able to see their students’ faces. This had a negative impact on the quality of mathematics instruction (see Table 10).

Table 10.

Number/percentage indicating that during ERT of mathematics, they never used each approach or only used it “to a small extent”.

As shown in Table 10, two thirds of the teachers (n = 40, 64.6%) indicated that during ERT they did not use ICT-enhanced inquiry-based mathematics learning at all or only used it to a small extent, whereas the vast majority also indicated making little or no use at all of collaborative learning (n = 54, 87.1%) and/or the differentiation of learning (n = 48, 77.4%) in mathematics instruction. As a result, two thirds of the teachers felt that they promoted the construction of new mathematical knowledge/skills by the students themselves only to a small extent or not at all. Four fifths felt that they managed only to a small extent or not at all to meet the needs of children with disabilities and/or additional educational needs.

In an open-ended question where teachers were prompted to describe what they did or could have done differently in mathematics to help their students feel closer to their classmates during ERT, teachers described various actions they took to ensure ongoing communication with their students, as well as among students themselves:

I prepared and sent podcasts to my students on a daily basis.

I talked daily on the phone with students and their parents and gave my feedback on children’s progress.

We had a Viber group with parental supervision, where students uploaded creative work for their classmates to see.

Our daily online chats helped children feel closer to their peers as they shared their experiences.

The platform opened 10 min before the class started, and in that time interval students could talk to me and their classmates about anything they wished to discuss.

Despite the actions taken by individual teachers, several participants noted the need for more active, collaborative learning of mathematics and other subjects: “It would be good to see their classmates during class. Assign group homework.”; “Chats, video presentations, presentations and peer review, participation in games, collaboration in handling tasks.”

When prompted to indicate the most difficult subject to teach during ERT, 40% (n = 25, 40.3%) selected mathematics, noting that “preparation for math lessons took longer than for other subjects” and also that they had difficulties “presenting mathematical concepts during synchronous sessions” due to the symbol-heavy nature of the subject.

Teachers were asked to indicate, based on their experience, how useful different tools and services would have been in supporting more effective ERT and ERL of mathematics and other subjects during the COVID-19 lockdown. Their responses suggest that teachers would have appreciated more opportunities for “ongoing” and “in-depth rather than hasty and superficial” professional development in the use of pedagogically sound strategies for online teaching and learning and in the effective use of new tools and technologies in mathematics and other subjects. Teachers also stressed the need for training parents and students in the use of eLearning and other digital technologies: “Teaching of informatics in primary schools for children to acquire basic ICT skills early on”. Teachers would have also liked the provision of examples/suggestions of good practices for the digital classroom, of “ready-made material”, of lessons that could be delivered via video/virtual conferences, and of digital platforms that provide online material for digitally enhanced teaching and learning. They also noted the need for improved access to the internet and/or to a trusted device for all students, for access to printing services for students, and for the provision of services for sending study materials at home. Tools and services that would have addressed the learning needs of vulnerable groups of learners (students with disabilities, students from a low socioeconomic background, etc.) were also pointed out.

In a related open-ended question where respondents were prompted to indicate tools/technologies that they did not have access to during ERT that would have facilitated their teaching, several noted that they would have liked access to a digital whiteboard, a digital pen, and to “better quality computers and software” for themselves and for children, so as to facilitate the more active learning of mathematics and other subjects. The need for “open cameras during the lesson” to “build a sense of community” was again repeatedly pointed out by many teachers, as well as the need for professional development in the use of e-learning technologies.

In a question where they were asked to judge the Cypriot educatonal system’s level of readiness for the adoption of synchronous long-distance learning methods, all the teachers responded either that it was not ready at all or that it was ready only to a very small extent: “Not particularly ready. Several shortcomings at all levels.”; “Not at all! It was a new unprecedented reality!!! It was caught off guard I would say”. The low level of preparedness of the Ministry of Education in managing the COVID-19 crisis and its lack of prompt and adequate support to teachers and students was a main theme in teachers’ responses:

The Ministry of Education did not do proper planning, neither did it take swift decisions that would benefit children.

Basically, the Ministry was not ready at all…it had not trained teachers. Even to this date, only 2-3 teachers from each school have been formally trained by the Ministry. The rest got familiarized with distance education on their own or with the help of colleagues.

Despite the low level of preparedness of the educational system and the challenges they faced during the transition to ERT, most teachers felt that they did everything they could to offer the best education possible to their students:

I believe that a lot has been achieved despite the challenges. We educated ourselves. We educated each other…much earlier than when the Ministry was ready to offer training to teachers.

The system was not ready but the teachers were ready to respond.

Synchronous and asynchronous remote education succeeded thanks to teachers’ persistence, professionalism, the endless number of hours they dedicated to this, and the use of the technological infrastructure they each had at home.

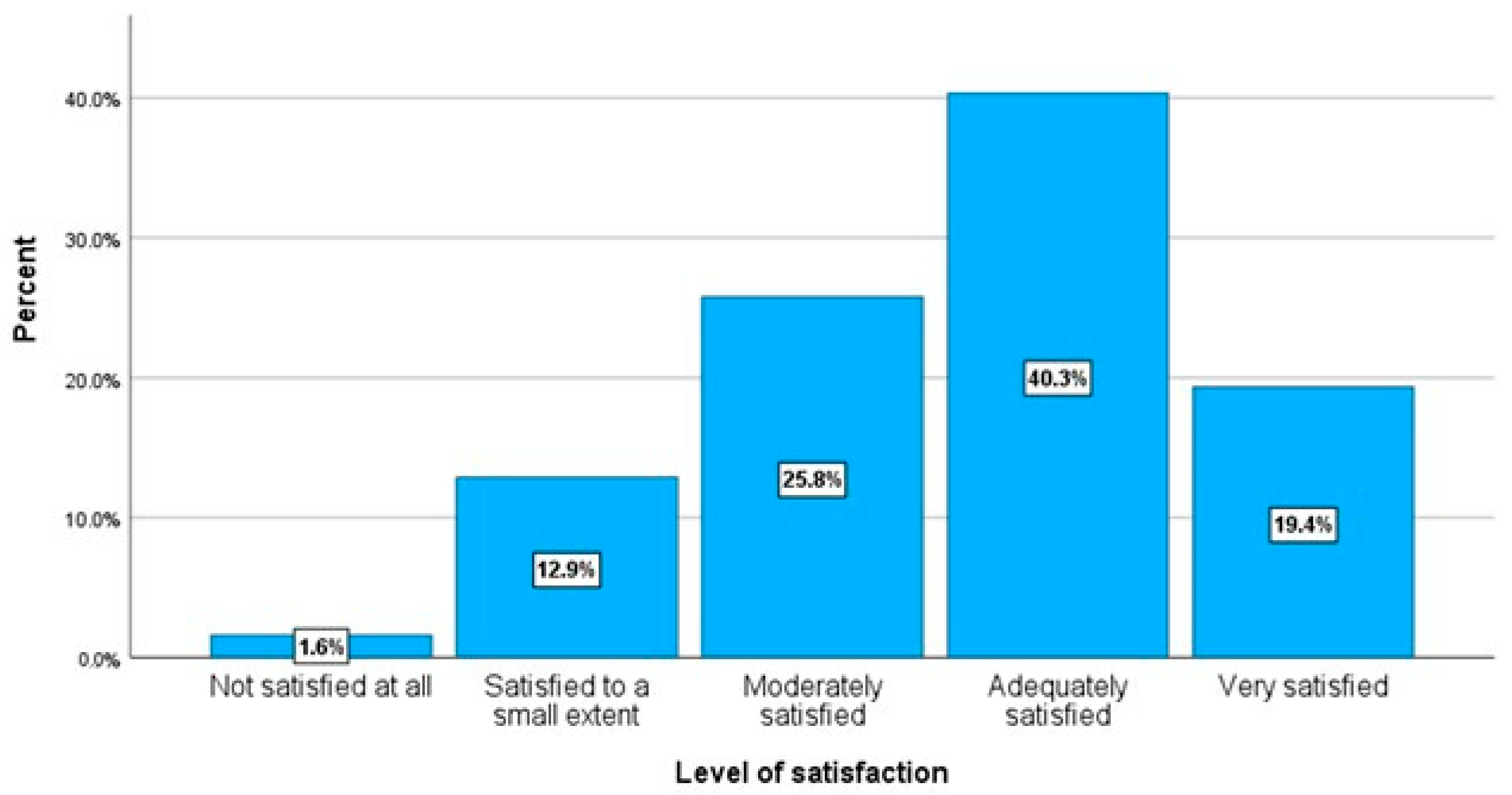

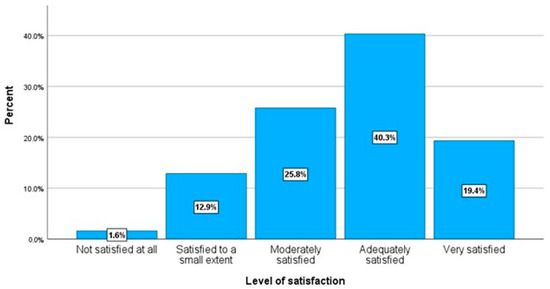

Figure 3 displays teachers’ responses to a question where they were prompted to indicate, using a 5-level Likert scale (1 = Not at all…5 = Extremely satisfied), their level of satisfaction with their performance during online lessons, and with their ERT practices in general. As shown in the figure, only 15% of the participants felt little or no satisfaction at all with their ERT practices. The remaining 85% felt at least moderately satisfied, with 60% feeling either adequately satisfied or very satisfied.

Figure 3.

Teachers’ levels of satisfaction with their performance during online lessons and with ERT practices in general.

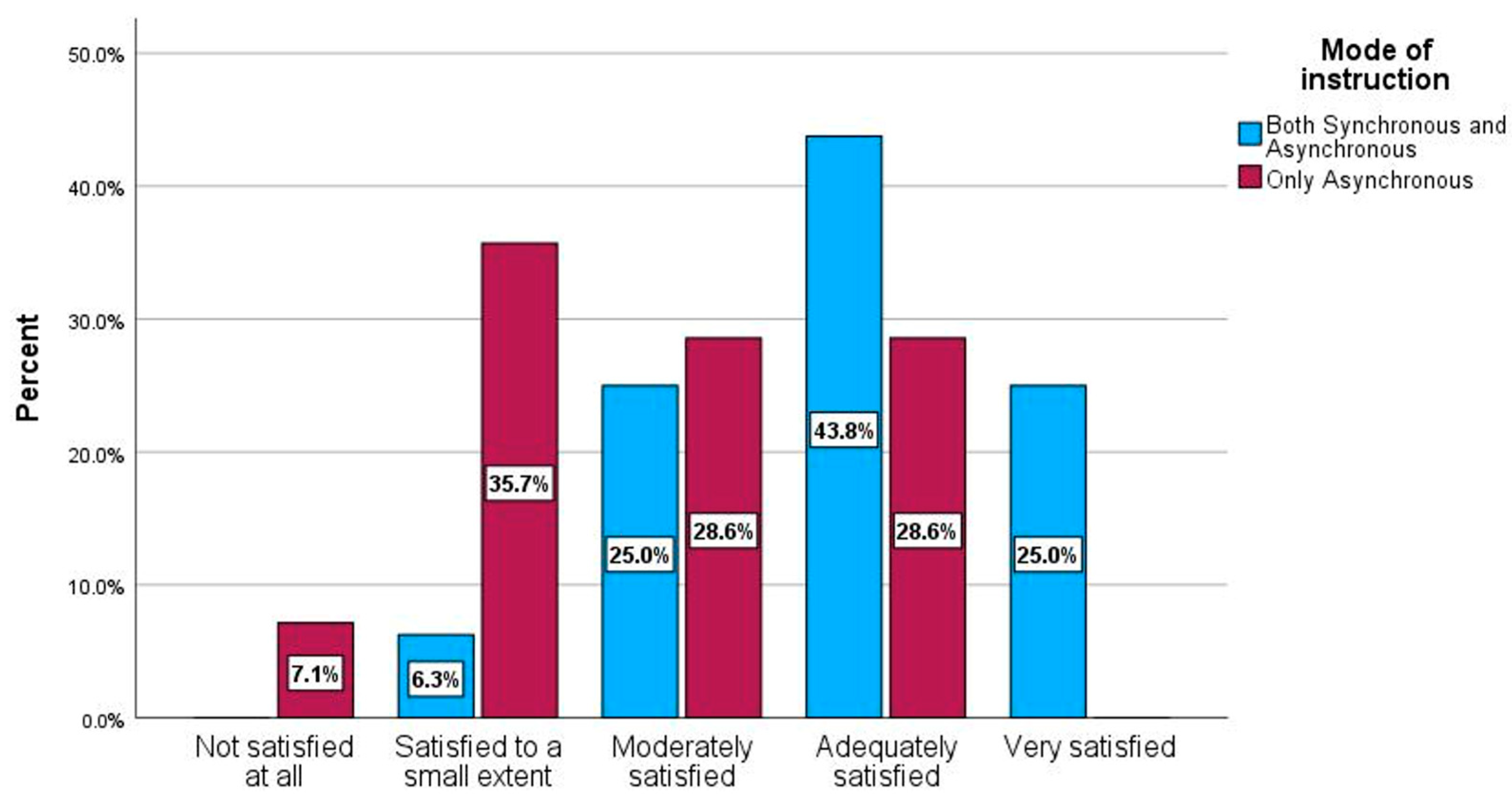

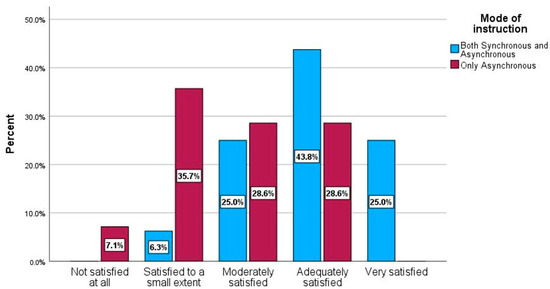

As shown in Figure 4, teachers’ levels of satisfaction with their ERT practices varied significantly based on whether they engaged in synchronous ERT or not (U(48, 14) = 145.5, z = −3.37, p < 0.01). Sixty-nine percent of the participants who engaged in both synchronous and asynchronous ERT stated that they felt very satisfied (25.0%) or adequately satisfied (43.8%) with their performance during ERT. The corresponding percentage for the asynchronous ERT group was only 29 percent. Additionally, although 43% of the asynchronous ERT group felt little or no satisfaction at all with their ERT performance and practices, only 6% of the group combining synchronous and asynchronous ERT selected this response.

Figure 4.

Teachers’ levels of satisfaction with their performance during online lessons and with ERT practices in general, separated based on whether they had engaged in synchronous ERT or not.

Teachers’ levels of satisfaction also varied significantly based on their technological expertise (U(31, 31) = 325.5, z = −2.29, p = 0.02 < 0.05). Although 71% of the teachers who had rated their technological expertise at the advanced or expert level felt adequately satisfied (41.9%) or very satisfied (29.0%) with their ERT practices, only half (48.4%) of teachers who had rated themselves at the beginner or intermediate level felt this way.

Similarly, teachers’ self-reported levels of preparedness for teaching at a distance also had a statistically significant impact on their level of satisfaction with their ERT practices (U(44, 18) = 278.5, z = −1.91, p = 0.049 < 0.05). Although almost 80% (77.8%) of the teachers who had rated their level of preparedness for teaching at a distance as high felt adequately or very satisfied with their performance as teachers during ERT, only around half (52.2%) of the teachers that had a low level of preparedness for distance education felt this way.

When reflecting on their experiences with the implementation of ERT, teachers highlighted not only the challenges they encountered in the transition to ERT, but also the unique opportunities that the pandemic had provided for the transformation of teaching and learning. Many noted the enhancement of students’ and teachers’ digital literacy skills and their familiarization with innovative e-learning tools and technologies that could be used to enhance the teaching and learning process.

Children became familiar with a new way of teaching and acquired important and useful skills that they will use for life.

Acquisition and cultivation of digital skills by students, exploration of alternative pedagogical approaches by teachers.

A number of participants also pointed out that the lockdown “gave children the opportunity to become more autonomous and to take a more active role in their learning process”. Several others referred to parents, arguing that the lockdown led to “more frequent communication with parents regarding children’s learning and progress” and to “improved relations between teachers and parents”. Finally, a couple of respondents also referred to the enhancement of involved stakeholders’ “crisis management skills”.

Teachers considered the turmoil caused by the pandemic to be an opportunity for fundamental changes to the educational system—the revision of curricula and pedagogical approaches, more effective integration of technology, the improvement of technological infrastructure, and the development of crisis-sensitive educational planning.

Finally, teachers were prompted as to whether they would continue using the tools and technologies that they became familiar with during the ERT period when the normal operation of their school resumed. More than 70% responded positively, stating either that they intended to incorporate the tools and technologies they used during ERT into their courses (n = 33, 53.2%) or that they were already using these tools and technologies prior to COVID-19 and would continue doing so (n = 11, 17.2%).

In the Results section, we presented the results regarding teachers’ self-reported technological backgrounds and levels of preparedness for ERT, the challenges they reported facing during the transition to ERT, the technological tools and didactic strategies they reported utilizing during ERT of mathematics, and their reflections on their ERT experience and the way forward for ICT-enhanced mathematics instruction in the post-COVID-19 era. In the next section, we summarize and interpret our key findings and link them to the relevant international literature.

5. Discussion of Results

In this study, we aimed to explore Cypriot primary teachers’ perspectives and lived experiences during the transition to ERT in the early stages of the pandemic. We focused on mathematics education because mathematics is a particularly difficult subject to teach and learn under ERT circumstances, and also because only a few of the previously published studies examining educational institutions’ transitions to ERT have targeted mathematics teachers. Through a national, in-depth survey of primary school teachers working in the public sector, our study investigated teachers’ prior technological backgrounds and levels of preparedness for teaching at a distance, as well as their perceptions, experiences, and reflections related to ERT of mathematics.

In the Discussion section, we summarize and interpret our key findings and link them to the relevant international literature. The discussion is presented in four subsections, reflecting the survey’s research questions.

5.1. Teachers’ Self-Reported Technological Backgrounds and Levels of Preparedness for ERT

Most teachers reported extensively using various technological devices and tools in their daily and professional lives. They also indicated that they had been incorporating various technological tools into their instruction of mathematics and other subjects prior to the pandemic. PowerPoint presentations and videos were the most popular technological tools. The majority also frequently used interactive applets and/or other educational software designed for teaching a specific subject. Around half reported regularly using cloud and file sharing platforms such as Dropbox and Google Drive. Smaller but sizeable percentages reported making frequent use of media sharing sites such as YouTube and Vimeo, online forums, e-books/e-readers, communication and collaboration tools such as blogs and Google Docs, and supportive technologies such as screen magnifiers. By contrast, most of the teachers reported that, prior to the pandemic, they rarely or never used e-learning tools such as online/electronic quizzes, podcasts/audio files, chats, discussion forums, breakout rooms, and online homework. The vast majority also made very limited use of simulations, gaming, virtual worlds, programming software, media editing software, and other interactive tools that can promote student motivation and active participation in mathematics and other subjects.

In the mathematics classroom, in particular, technology was often used before the pandemic. Around 70% of the participants reported having regularly used mathematics education applets, and around 60% reported having used other subject-specific software. Software supporting dynamic geometry such as Geometer’s Sketchpad was employed much less frequently—only around 30% of the teachers often used such software.

Although almost all teachers reported an intermediate or advanced level of familiarity with technology and the use of various technological tools in their instruction, about 70% stated that, at the onset of the lockdown, they were slightly or not prepared at all to start synchronous ERT. Most of the respondents had not participated in any distance learning programs as either trainees or trainers in the past, nor had they participated in any training related to distance education.

Similar findings have been documented in other research papers, such as in [42], where the authors concluded that although the secondary mathematics teachers in their study were previously trained in terms of different specific types of software for teaching mathematics and ICT tools, they tended to believe that they needed more preparation for remote teaching. Furthermore, the authors in [57] discussed how the K-12 teachers in their study felt overwhelmed and unprepared to use ERT strategies and tools. Similarly to the teachers in our study, most mathematics educators in [57] became familiarized with online and remote teaching strategies and tools while teaching online or remotely (aka “building the plane while flying it”). The authors in [57] also reported that, in shifting to ERT, teachers mainly relied on informal self-directed learning and support from their professional learning networks. South African secondary mathematics teachers in [1] also had to adapt during the pandemic to become learners themselves as they learned to support their students through the adoption of ERT methods and previously unexplored digital platforms and tools. They too had to quickly adapt to ERT and to come up with effective solutions in less-than-ideal conditions, so as to set up a digital environment for their class.

Keeping up with technological advances and their use in education is therefore imperative for all current and future teachers. This is discussed in [6], where the authors emphasized how ICT skills are particularly important given the radical shift towards online teaching during the COVID-19 lockdown in many OECD countries. The need for training existed even before the crisis, when teachers reported a strong need for training in the use of ICT, with 18% on average across OECD countries identifying this as a high training need [38]. This was the second most common training need that teachers identified, just after training regarding the teaching of special needs students. In [58], teachers perceived themselves as being partially competent in ERT. Moreover, teachers thought that they were skilled in the use of digital tools for general communication but felt less confident concerning the use of specific tools to facilitate the teaching/learning processes. Similarly, [17] stressed the need for teachers to be equipped with different types of digital skills that will enable them to combine the instructional use of digital tools with well-founded pedagogy that can facilitate students’ learning and enhance the development of their digital competences.

5.2. Challenges Faced by Teachers during the Transition from Face-to-Face Instruction to ERT

The vast majority of both teachers and students in Cyprus had never had the chance prior the pandemic to use the online platform provided by the Ministry of Education for online classes (Microsoft Teams). In order to enable the use of the platform, teachers and students had to obtain their account details from their schools, set up the application on their computers, and familiarize themselves with it. Setting up new accounts for students took some time, given their large numbers. Furthermore, even after setting up their accounts, both teachers and students needed some basic technical knowledge to install and get the application running [25]. Given that schools were closed, this whole process of setting up the platform and signing-in required good remote communication between the students and the teachers. At the beginning of the lockdown, most teachers took the initiative to contact their students and start asynchronous teaching with parental guidance. In addition, many of the teachers started synchronous teaching using freely available platforms other than MS Teams such as Zoom, Skype, etc. MS Teams became the official platform endorsed and supported by the Ministry of Education, but it took several weeks until the platform was ready for use by teachers and their students.

Most of the participants criticized the low level of readiness of the Cypriot educational system for the adoption of synchronous ERT methods. Teachers strongly expressed their belief that the Ministry of Education was not well prepared to manage the COVID-19 crisis and did not adequately support teachers and students during ERT. However, despite the low level of preparedness of the educational system and the challenges teachers faced during the transition to ERT, most educators felt that they did everything they could to offer the best education possible to their students.

Many of our study participants identified students’ discomfort or lack of familiarity with the required technologies as a major challenge. They also reported that some of their students did not even have access to a PC or a tablet and/or to the internet and that most children had never had any prior experience with communication platforms such as MS Teams or Zoom. As teachers pointed out, their students—and especially the younger ones—required parental guidance to be in front of the screen for a long time and to participate in their online classes. While students were struggling to connect, turn on their microphones, mute themselves, etc., many of the parents had to interrupt their (online) jobs to support their children during their classes. In addition to this, they also had to deal with their own lack of familiarity with e-learning technologies.

The technical challenges that our study participants had to face and the limited time in which they had to prepare for their online classes prevented most of them from using specialized mathematics software or applets during ERT. Another possible explanation could be that these types of software require high processing power and high-speed internet connectivity and, combined with MS Teams, they slowed down the teachers’ outcomes.

Overall, the majority of the teachers felt that they were not well prepared to start ERT. They did not have any training related to distance education prior to the lockdown and, additionally, they did not have official guidelines from the Ministry of Education regarding how to proceed during the transition to ERT. Their main source of support and guidance was peer support. As a result, teachers identified an excessive workload as a major challenge during ERT.

Our research findings are in alignment with the international literature [32,33,38,43], which indicates that the challenges faced by teachers and students during ERT were multiple and similar in nature globally. The findings of [18], for example, suggest that the preparation for ERT had to be completed within a very short timeframe, and as a result teachers and students were not properly equipped for ERT. To alleviate any obstacles occurring during the implementation of ERT, many researchers pointed out the need for student and teacher training in e-learning tools and methods [25,26,59,60]. In a study conducted in Greece to investigate pre-school mathematics teachers’ practices during the pandemic [21], teachers stated that they did not use the platforms (WebEx, e-me, and e-class) indicated by the Greek Ministry of Education. The main reason for this, according to the teachers, were barriers such as the lack of opportunities for teachers’ professional development in distance education, the lack of equipment or internet connections in schools, and children’s lack of familiarity with distance learning. Students’ lack of familiarity with distance education is particularly challenging in pre-school settings, such as the context of [21] or primary school settings such as those in our study, due to the young ages of the students and the need for greater parental involvement [40].

In addition to the above-described challenges, our study participants also faced additional challenges in teaching mathematics. A high proportion of the teachers who taught mathematics during ERT identified mathematics as the hardest subject to teach remotely. They stated that although they often used student-centred approaches such as group work and the differentiation of instruction prior the pandemic, these practices seemed very difficult to employ during ERT, since students could not actively participate during the online classes. Additionally, students had their cameras disabled when using MS Teams and this made interaction and efforts to actively engage students impossible. Mathematics is by nature a “social” subject. The teacher and his/her students interact by giving feedback to each other through various means such as facial expressions and gestures to ensure that the new concepts are understood. Without a web-camera, visual interaction was not possible. Similar findings were reported in [13], where one of the main challenges identified was related to how teachers organized interactions (teacher–student, student–content, and student–student interaction) in long-distance settings. The authors in [13] highlighted the need for more and better pedagogical and technical training for teachers, as well as for clear guidelines from universities regarding online learning as a basis for teacher practices. Limited student participation and interaction was identified as the largest disadvantage in regard to distance education in [18]. This is also supported by the findings of [20], which examined the perceptions of teachers, administrators, and academics in Turkey regarding the challenges of distance education. Among the most serious obstacles reported were those of limited communication and difficulties in attracting students’ interest during virtual class. Participants stated that they could not effectively communicate with their students and thus could not be certain as to whether students were attentive during class. Moreover, the pre-school mathematics teachers in [21] referred to continually reduced interest among students, since young children prefer direct contact and communication with their teachers and classmates. Due to the young ages of their students, the teachers in our study also experienced similar challenges in communicating with their students at a distance.

5.3. Didactic Strategies and Digital Tools Utilized by Teachers during ERT of Mathematics and Comparison with the Strategies and Tools Employed Prior to the Pandemic

There is very limited literature discussing the digital tools used by elementary school mathematics teachers during ERT. In a study involving primary and secondary school mathematics teachers in the USA [36], participants reported that the largest influence of ERT on their in-person mathematics teaching was in the use of general, non-mathematics-specific technologies. The organization of their face-to-face mathematics classrooms after the reopening of schools was influenced by the use of apps such as Peardeck, Seesaw, Google applications, edPuzzle, and other non-mathematics-specific digital technologies which they used during their virtual mathematics teaching, and continued to use when switching to in-person settings. Another study [61] describes how teachers in Singapore used a variety of software applications for their online lesson delivery, such as video conferencing software (e.g., Zoom or WebEx) to create their virtual classrooms, a central repository to house relevant digital resources (e.g., SLS), a communication platform for the dissemination and exchange of information (e.g., email systems), assessment applications for the monitoring of students’ progress and learning, and discussion forums to support students’ exchanges of ideas and discussions (e.g., Padlet or Google Classroom). A similar approach has been reported for secondary education, where mathematics teachers tried various software solutions and tools in order to conduct their mathematics classes online. For example, teachers in [22,46] cited the increased use of online applications, learning systems, and graphing applications and computer algebra systems.

The findings from our study conflict somewhat with the existing literature. According to our results, during ERT there was a slight increase in the level of use of PowerPoint presentations, lectures/seminars that used screenshots and narrative presentations, asynchronous discussion forums, synchronous chats, breakout rooms, podcasts/audio files, online homework assignments, and online quizzes. Furthermore, some teachers also used instant messaging and/or social media to communicate with their students. This was not a common practice prior to the pandemic primarily due to their students’ young age. At the same time, however, although around half of our study participants reported using mathematics education applets and/or other software designed for mathematics education on a daily or weekly basis prior to the pandemic, these percentages dropped somewhat during ERT. In order to adapt under the harsh new conditions, teachers had therefore decreased the use of both general-purpose and subject-specific software, open-source instructional material, eTextbooks, and associated online content. The use of interactive tools and technologies such as digital games and simulations continued to occur at similarly low levels to those prior to the pandemic.

5.4. Teachers’ Reflections on Their ERT Experience and Conceptualizations of the Way Forward for Technology-Enhanced Mathematics Instruction in the Post-COVID-19 Era