2. Theoretical Framework

This research draws on the dialogic perspective of Bakhtin to explore how student teachers reflect on insideness and outsideness to inform their pedagogical understanding. While a dialogic perspective has often been used to focus on the language and discourse in education, this perspective provides a sensitive theorisation of relationships between individuals, within communities, and in relation to the wider world [

7]. From this perspective, individuals are understood to occupy a unique place in space and time [

44]. Bakhtin’s enduring interest in time-space, the chronotope, offers a sophisticated theoretical tool for exploring the interconnectedness of time and space as an environment for being and becoming [

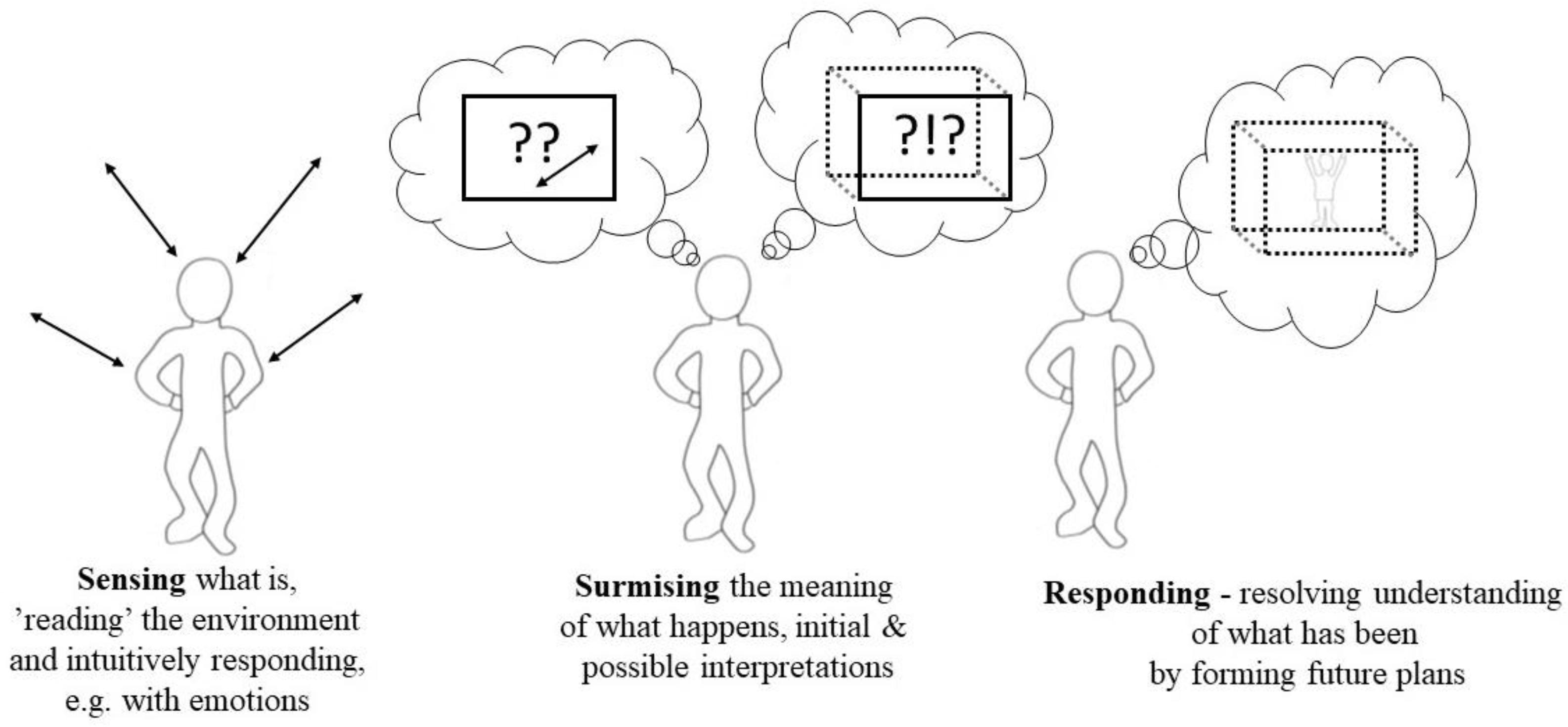

47], and to explore how individuals continually sense, surmise, and respond to their environment [

48,

49].

The immediacy of sensing, the initial meaning ascribed by surmising, and the greater thoughtfulness of responsiveness complement Clarà’s [

8] definition of reflection as ‘the unclear situation; the problem; the idea (inference); the observation of the coherence between the idea and the observed events and previous knowledge; and the reaction of the situation to the introduction of the idea’ [

8] (p. 270). It is this interplay that generates dialogues in which past experiences, voices, and authorities are used as resources to anticipate and form potential action and pedagogical development [

29,

50].

Figure 2 illustrates the changing quality of reflection, from intuitive sensing to an initial surmising to, at least, a temporary resolving of understanding through the formation of future plans from a dialogic perspective.

While different voices, authorities, and experiences contribute to this dialogue, student teachers have the final responsibility for who they become as educators [

44,

51,

52]. Bakhtin conceptualised this dialogic relationship between an individual and their environment as a journey through a landscape [

44]. If a hero travelling through space and time remains untouched and unchanged, that is ‘self-centred’, the hero remains under-developed [

53]. However, if the ‘hero’ learns to ‘read’ the landscapes and look with a ‘slower’ eye then the engagement with the world is richer and a fuller self develops [

44]. For Bakhtin, Goethe was a key example of engaging with a slower eye, and Goethe’s account of his Italian journey [

54] outlines how he sought to develop a ‘slower’ eye, for example, by drawing the natural world as drawing required him to deliberately stop, look, reflect, and engage with the world modelling an eco- rather than ego-centred approach to education [

28].

Bakhtin’s response to Bildungsroman—literature dealing with potential, reality, and creative initiative—commends human becoming that transforms from being a private affair in a stable world in which individuals are required to ‘adapt’ to the world ‘… to recognise and submit to the existing laws of life’ [

44] (p. 23) to becoming a public affair, which involves not only the becoming of individuals, but individuals and the world. This differentiation between education as a private or public affair again anticipates the distinction between ego- and eco-centric education [

28,

38]. Moreover, from a dialogic perspective as an individual ‘emerges along with the world and he [sic] reflects the historical emergence of the world itself’ [

44] (p. 23). In other words, each individual contributes to and is formed through the ongoing story of the world authored through the responsive acts of particular individuals at particular moments in space and time [

55] underlining the emergent realism of a dialogic perspective [

56].

From a dialogic perspective, it is the particularity of individuals within particular moments that avoids the over-abstraction of understanding that can undermine ethical relationships [

44,

51,

55]. For Bakhtin, it is through relationships with particular others that a sense of self is formed, such as through the words of a mother in relation to an infant [

51], through responses to someone else’s pain [

51], or by recognizing the questions of outsiders as opportunities for mutual enrichment [

44]. A dialogic perspective recognizes humanness not in abstracted truths, but in encounters between self and others. It is this perspective that can perhaps help with understanding why education is irreducible to technique or theory; education always involves relationships with particular others, in unrepeatable moments with profound implications for what students come to know and how they live in the world [

28,

31,

38].

The IP in this study was a deliberate attempt to interrupt the assumptions and existing understanding of the student teachers by drawing their attention to notions and experiences of insideness and outsideness. Whilst teacher educators can seek to encourage engagement with different voices and spaces, it is students themselves who are ultimately responsible for their pedagogical understanding. The research task underpinning this study is to gain a better understanding of how students transform ‘ways of being’ into ‘ways of knowing’ that inform pedagogical understanding. The research questions underpinning this study use the distinct, dialogic phases of sensing, surmising, and responding to explore the formation of pedagogical understanding in relation to notions of insideness and outsideness.

How do the student teachers use key moments as resources to respond to notions of insideness and outsideness?

What did the student teachers initially surmise in response to these key moments?

How do sensing and surmising inform the pedagogical understanding of the student teachers in their reflections?

4. Findings

This section outlines the findings and begins by outlining the key moments that student teachers use as resources as they seek to make sense of insideness and outsideness. The personal tenor of these examples indicates how important it is for student teachers to have the opportunity to work through and with their own experiences as useful starting points concretising abstract notions. The middle section of the findings outlines what meaning the student teachers initially ascribed to these examples, that is, their preliminary reflections. These findings are important as they indicate the sensitivity and thoughtfulness of the student teachers and highlight how initially ascribed meaning can appear finalized. As the findings to the third research question indicate, however, over time this understanding can continue to change, to be enriched or undermined. Indeed, a key contribution of this study is to highlight the value of ongoing dialogue and of paying attention to the personal examples that students use to make sense of abstract notions, while also seeking to expand the dialogue beyond student teachers’ own examples to enable them to work well in diverse educational communities. In the findings, verbatim text from the participants’ texts is italicised and followed by a reference to the participant to give the reader a better sense of the individual nature of the students’ reflections as well as the shared quality of their reflections across the dataset.

4.1. Key Moments as Resources to Explore Insideness and Outsideness

The participants’ texts include a broad range of key moments that they used as ‘anchors’ for sharing their experiences and as resources for developing their understanding. These key moments include remembered experiences of different places and environments as well as relationships with other people. For many participants, key moments of insideness were sensed in relation to that which was familiar—‘my’ group, a place with friends and family, with people who shared the same passion or interests, belonging, and being connected. The emotional intonations associated with insideness were often positive—safe and reassuring (P1), special (P2), accepted and respected (P6), rooted (P13), happy and able to learn (P16), a ‘natural spot’ (P21), creates meaning (P22), welcoming (P2), and at home (P6, P16, P22, P23).

Outsideness was sensed when entering new spaces—the course, schools, places of work, and exchange periods. In addition to physical or architecturally different places, however, the participants’ texts also indicated the significance of different types of activities and relationships, such as drama, the Dérive, and meeting and discussing with new people as events that signified stepping outside of one’s comfort zone or encountering something new. Emotions associated with outsideness included agony and exhaustion (P6), reduced confidence (P7, P16), silly and terrible (P7), threatened and exposed (P22), stressed (P22, P30), unwelcome (P23), uncomfortable and overwhelmed (P17), and rejected and confused, as well as peace and freedom (P15). The emotional intonations of the terms used to describe the sensation of insideness and outsideness indicate the significance of these experiences for participants and their intuitive explanation as to why these experiences were meaningful.

The temporal frame of these key moments greatly varied—from short moments as part of everyday life, such as skateboarding in the local city (P12) to longer term periods of living abroad (P6, P7, P8, P10) to the ten-day IP–‘the first time that I observed consciously my situation abroad’ (P1)—suggesting that it is not the duration of an event, but the meaningfulness of the moment that is attended to. In addition to new experiences that prompted reflections on outsideness, however, re-reading their own initial reflections was also significant for several participants (P4, P5, P9, P16, P17, P18, P24). Participant 9 commented that ‘Sometimes it is hard to believe how your opinions and ideas about something can change so much in just a few days… Now, reading my pre-task… I realise that I Was just focusing surface of these concepts…’, and Participant 17 wrote, ‘If I read my precourse assignment today… I am astounded by my one-sided understanding of insideness and outsideness’. Although these words might be somewhat idealised (the intended audience of the text is the course instructor), going beyond the opening words of these assignments the participants share in more detail why they are responding in this way to their own earlier assignment (see below). These findings suggest that re-viewing one’s own words from a different vantage point can be significant in the formation of understanding and that initial associations or sensations of inside-as-positive and outside-as-negative can be questioned as participants revisit key moments. Moreover, it is noteworthy that although these anchor points are perhaps mundane in some senses, they give rise to powerful emotions also used to inform understanding.

4.2. Surmising Significance

The surmised explanations of the students focus on the meaningfulness of their experiences after further reflection. The positive emotions associated with insideness continue to be present as participants surmise the significance of insideness. For several participants, insideness involves being connected (P1, P9), identifying with others (P14), sharing similarities (P18, P19) and passions (P9). Moreover, insideness is bestowed (P13), a ‘way in’ needs to be provided (P9) as though ‘inside’ is a bounded entity. On the other hand, some participants began to reform their initially positive statements, recognising that insideness can bestow privileges to some (P12, P24), it can be abused (P20), it is insufficient in itself (P9), it can trap (P23) and induce the adoption of inappropriate behaviour (P8, P25) and dangerous ‘habits’ (P20). These two different orientations indicate quite different ways of responding to insideness and point to the possibility of going beyond initial assumptions to develop a richer understanding.

Although the emotions associated with experiences of outsideness were often negative, as the participants surmise the significance of outsideness their intuitive responses are enriched. As Participant 30 wrote, ‘I myself like the feeling of insideness, to belonging to a group and to feel safe. But sometimes in my life a [sic] made the experiences of being outside, and often, these were the moments in my life which made me grow’. Many participants recognised the generative potential of outsideness (P4, P13, P15, P20) through the increased consciousness it created (P1, P17), the different perspectives it provided (P4, P5, P9, P11), the space for reflection (P12, P15), new acquaintances (P1), inputs (P11), and empathy for others (P10) as well as the opportunity for change (P1, P11) and initiative (P13) and the role of power (P8) and difference between personal responses (P14). This surmising often points to the heightened awareness of being in a new place (physical, relational, conceptual) as well as the way in which it was suddenly ‘realised’ that now they could see more and that earlier limitations had been surpassed (P9, P18, P24). This sense of epiphany highlights the plasticity of understanding that can change and develop over time in turn highlighting the importance of prompts and encouragement to look again from different perspectives, to not be satisfied with initial impressions. It is also this epiphanic quality that separates the surmising of the participants from their more pedagogical responses to insideness and outsideness.

4.3. From Surmised Meaning to Pedagogical Responses

As the participants anticipate their future role as educators, their responses are more extensive, and their understanding of insideness and outsideness is reformulated as principles to inform potential action. Whilst some participants explained insideness as a ‘basic’ or ‘human’ need (P3, P7, P18, P22), the explanations tend to acknowledge insideness as a tenuous relationship (P22) that should not be assumed or accepted without question (P12). Participants also pointed out that insideness requires commitment (P6, P20, P23), a relationship that requires on-going reflection (P8, P20), as this relationship is with and ‘between’ others, yet an individual should remain responsible for him/herself (P14, P23, P25). This conceptualisation corresponds with the initial responses to insideness as a mediated relationship, yet the participants seem to acknowledge their responsibility within this relationship, rather than having this position bestowed upon them. Moreover, the participants begin to recognise insideness as transitory (P14, P16) with degrees of insideness (P9), rather than a bounded entity. Some participants noted that it is possible to opt out of insideness (P11, P12, P17).

The participants’ texts also provide examples of actions and conceptualisations in response to outsideness. Actions include asking new questions (P1, P6, P16), revaluing opinions (P1, P6, P15, P17), being inspired to act (P2, P13, P15, P26, P2), and recognising the value of outside perspectives as resources for better understanding—seeing more or differently (P4, P5, P8, P9, P10, P12, P13, P18, P24). Outsideness was also responded to in terms of mediation and transition—as something that can be reduced through action and/or design (P1, P12, P22, P30), albeit challenging (P9, P13), and participants acknowledged the way in which outsideness can compromise potential contributions (P23), hamper engagement (P7), be subject to cultural and social pressures (P11) and involves risk (P20). In these responses, the positive and negative sides of outsideness are more readily acknowledged, and the clean-cut edges of outsideness are chipped away by suggestions that outsideness can on occasion be chosen (P11) or experienced even if an individual is accepted by others (P9).

As the participants continue to share their responses to insideness and outsideness, they also begin to share the way in which insideness and outsideness work as complementary notions. Participant 1 explicitly remarks ‘that I could keep my identity there’, that is, within the national group whilst participating in the InOut IP, and acknowledges the value of discussing with other participants as, ‘when they shared their views on pedagogical topics … I could think over and revalue my opinion’. Whilst on the one hand the ‘home’ group provided a foundation, the intercultural dialogues of the IP participants supported careful rethinking as the participants go beyond their initial experiences and begin to see and understand their experiences in new ways. These findings suggest that the participants are moving towards pedagogical understanding that is open to questions and contradictions and perhaps sympathetic to the experiences of others. As the participants share their potential pedagogical practice as future teachers, however, the relationship between insideness and outsideness is increasingly idealised.

4.4. From Enriched to Idealised

As the participants turned their attention to the responsibilities of teachers, several participants emphasized the need to be aware of and to preserve pupils’ identities and uniqueness (P1, P2, P10, P12, P13, P15, P21, P27, P28) by establishing an inclusive, welcoming atmosphere (P3, P10, P13, P17, P20, P27) to help pupils experience a sense of existential insideness (P4, P22, P26, P28). As future teachers, the participants expressed the desire to be responsible, sensitive examples (P8, P9, P10, P20, P23), available to students (P17, P21, P22, P26, P30) in order for their pupils to also learn to value diversity and to be inclusive. In these accounts, teachers are positioned as key mediators—almost gatekeepers—of insideness. Participant 22 writes, ‘When people are included to the process, then they have opportunity feel as insiders. And our communication skills, temperament, cultural background, creativity, all our back[g]round makes us insideness of humanity’. In a similar vein, Participant 24 says, ‘It is time for education to invite learners to the inside. It is time for education to have purpose… For how are they else to create an environment that invites learners to create their own educational identity and sense of place?’

These are indeed ‘noble’ goals, as Participant 26 notes, and the missionary tone of the participant texts—with mission being the word used by two participants themselves (P21, P28) when referring to their future work as teachers—is striking. These statements of pedagogical intent are reminiscent of the initial sensing of insideness, yet the struggles, challenges, and affordances of outsideness seem minimised. Three participants observe that the system needs to change for these hopes to be realised (P15, P28) and to avoid pupils ‘inherit[ing] what the hegemonic norm tries to impose’ (Participant 11). These findings seem to suggest that although the big picture from the participants’ accounts demonstrates a richer understanding of insideness and outsideness, when the participants look to the future as teachers, their reflections lack the complexity of their earlier reflections. As Participant 30 says,

I myself view insideness as something positive people should try to reach. An important aspect of insideness is the safe frame it can give you. If we feel safe and enclosed we are much more willing to stay at the place where we are and to develop.

The implications of the conclusions drawn by the student participants are the focus of the following discussion.

5. Discussion

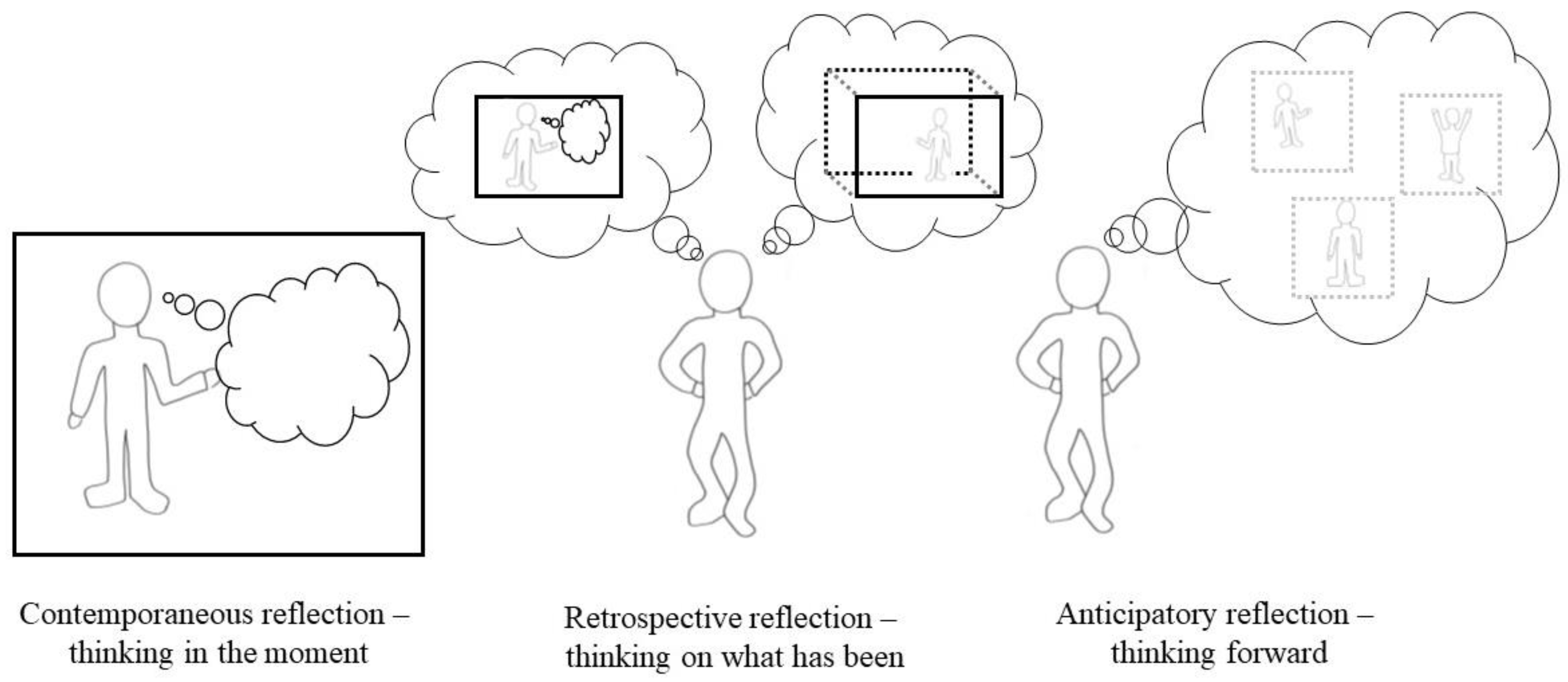

This study explored how 30 student teachers formed pedagogical understanding in response to a ten-day IP focused on notions of insideness and outsideness. The three research questions focused on resources student teachers consider as significant in their initial explanations, their more abstracted responses, and potential action. Using a dialogic perspective, the key moments in the participants’ texts that shared experiences of insideness and outsideness were considered as sensing, surmising, and responding [

48,

49]. This dialogic perspective complements the temporal distinctions of contemporaneous, retrospective, and anticipatory reflection [

18]. Furthermore, this study indicates how the quality of student teachers’ reflections can vary as they navigate what is and negotiate what could be.

The findings indicate that the participants initially attend to concrete and personal events and experiences as the material for forming understanding [

61]. These events and experiences are often keenly felt and emotionally intoned [

58,

60]. These concrete, personal experiences provided a useful starting point for going behind and beyond individual memories to surmise what it means to experience insideness and outsideness. As the participants surmised the meaning of personal experiences, potential connections begin to form between different experiences, for example, the feeling of being accepted, albeit in different communities or at different times. Through these activities, it becomes possible to empathise with others who have different experiences and to see from different perspectives, enriching the ethical reflections of the participants [

21].

Using the dialogical lens of sensing-surmising-responding it is possible to follow the gradual formation of the participants’ pedagogical understanding as they become more aware of their own thinking, the significance of their experiences, and new ways of understanding. These findings highlight the value of student teachers’ own experiences as a starting point for developing pedagogical understanding with space for contradictions [

39], questioning [

36], and ruptures [

40], rather than temporal proximity. Re-viewing these key moments, whether from the distant or recent past, leads to significant shifts in understanding, which also needed further consideration and reflection. As Participant 16 wrote, ‘

When I got home though, I didn’t really feel like home anymore. Some part of me had change, and I’d learned and experienced things with people who weren’t surrounding me anymore and this made me feel a bit as an outsider. This really confused me’. The profundity of this experience is particularly significant as few teachers experience the disruption of forced immigration or relocation, yet through personal experiences they can perhaps begin to understand the profound implications of these experiences and respond with greater sensitivity.

The participants’ experience of time is also an important feature as pedagogical understanding takes shape. That the participants included distant as well as recent events also suggests that the temporal frame of meaningful dialogue can be ‘stretched’ over longer periods or compressed. This is perhaps the notion of ‘great time’ that Goethe entered into as he looked at ancient structures as part of a living culture or read the weather from the landscape [

44]. As the participants responded to events, whether in the distant or recent past, and re-considered and re-responded to them, by theorizing their experience [

41], these events and experiences became part of a dialogue that disregards time—or timespan—as a measure of meaningfulness or relevance. This suggests that in the formation of reflective dispositions [

16,

17], it is important to keep the dialogue alive, to remember to look with a slow eye, to meet with the particular others in educational communities and to be sensitive to their experience and their being and becoming [

4,

5], and to allow for uncertainty to be part of education [

44,

45].

The contrast between the sophisticated participants’ responses and their potential pedagogical practice requires further attention. When the participants revisited their experiences, their responses become more abstract as statements of understanding in which they recognise the complexity of insideness and outsideness, problematizing simple designations of insideness as good, outsideness bad [

36]. The quality of these personal insights, however, does not inform their pedagogical responses reiterating Clarà’s [

8] observation that reflection does not guarantee learning. In the participants’ responses, that is in their anticipatory reflections, the negotiation of insideness and outsideness is discontinued; these struggles appear resolved. There is no consideration of what resources or qualities outsiders can bring to communities, nor what it might mean for a newcomer to be merged, even submerged or questioned within a community [

35,

40]. These lacks arguably demarcate the limits of the students’ anticipatory reflections potentially stymying contemporaneous reflections in the field when encounters are no longer abstract considerations but lived experiences [

10]. If open arms are not positively received, if other students struggle to accept newcomers, if teachers forget how to harness struggles and ruptures or the experiences and qualities of new arrivals, then the cost to individuals and educational communities will continue to be unnecessarily high [

4,

5].

This study highlights the significant challenge of negotiating pedagogical understanding. Whereas in their own experiences the students have to navigate what has been and then negotiate what this means, when stating their pedagogical intentions the participants actual others are absent [

9,

10,

32]. This is perhaps why the pedagogical intentions adopt a missional tone and overlook the discomforts and challenges of both insideness and outsideness. Rather than problematizing and recognising struggles, the participants paint pictures of idealised classrooms with arms wide open to ‘outsiders’ ready to bring them ‘in’. These dogmatic statements of good intent seem to drop out of the bigger dialogue the participants had just entered into, in effect tightening and prematurely curtailing their pedagogical understanding [

36,

39].

This idealising tone, however, is potentially a useful indicator to student teachers and teacher educators that reflections are not serving the purpose of enriching pedagogical understanding [

15,

18,

50]. Dogmatic mission statements are more akin to the Bildungsroman narratives in which human becoming involves ‘submit[ting] to the existing laws of life’ [

44] (p. 23) rather than recognising that human development should also involve the development of the world. The expressed pedagogical intent tends to address an established system and assume a clear role, without considering whether their ideals will be accepted, whether welcoming ‘arms’ are adequate for mediating insideness, or what to do if newcomers are not grateful for the kind of welcome that is offered. It is difficult questions such as these that emphasize the importance of recognising that the world is also ‘in process’ and that student teachers’ actions and assumptions contribute to the historical becoming of the world as well [

56].

These finding reiterate the complexity of reflection as a practice and as an area for ongoing investment [

11] as well as an area for further exploration and theorisation [

8]. Existing research has drawn attention to the temporal quality of reflection and the importance of looking forward, as well as looking back [

9,

18]. The research reported here also draws attention to the quality of the reflections themselves, whether an intuitive sensing, an initial surmising of meaning, a carefully considered response, or a statement of future intention. As with Clarà’s [

4] observations, this study illustrates that reflection does not automatically lead to the making of good decisions nor the linking of practice and theory [

14]. However, by paying attention to the overall and varying quality of student reflections it is perhaps easier to move towards ‘better thinking’ [

11,

12].

At this juncture, it is important to return to the role and responsibility of teacher education. As in earlier studies, the different activities and relationships of the IP appear to foster awareness among the participants [

24,

29]. As participants reviewed their earlier texts, they expressed surprise and saw in new ways suggesting that through these activities and relationships of the ten-day IP, the participants began to enter into a bigger dialogue that went beyond themselves [

38,

44] and to actively draw on the complexity and open-endedness of intercultural encounters [

36,

60] to form pedagogical understanding. While the significance of the reported insights suggests that their insights were becoming part of a richer dialogue [

30], the dogmatic nature of their pedagogical statements challenges this assumption.

These findings suggest that a significant pedagogical dilemma of teacher education is how to support student teachers to enter into and actively sustain pedagogical understanding as a dialogue and the importance of developing reflection as a shared and individual aspect of teacher education [

11]. Arguably, pedagogical understanding needs to acknowledge lack of understanding as well as expertise, openness to otherness as well as sensitivity to self, an ongoing dialogue and sense of responsibility, and willingness to be comfortable when uncomfortable [

36]. Framing pedagogical understanding as an ongoing dialogue with concrete others, as well as with socially, culturally, and historically important voices, and as a foundation for ethical actions [

29], is hopefully an important step towards the development of education as a sustainable and responsible endeavour in—and between—times of crises. Moreover, bringing the next generation into this dialogue can perhaps better prepare student teachers for the sense of disruption or confusion that can surround moments of crisis. If more educators participate in this ongoing dialogue, there is perhaps greater space for encountering and living alongside others in a more equitable and mutually beneficial manner.

5.1. Limitations and Further Considerations

One limitation of this study is that it was conducted by a single author, although the IP was developed and designed by a much larger team of international educators. To support the integrity of this study, however, the researcher sought to check, question, and theoretically interpret the findings and to present earlier versions of this study to the wider educational community to receive feedback during the study. The integrity of the study is also supported by the use of dialogic approach that avoided fragmenting the reflections of the participants and sought to be sensitive to the individual accounts of the participants. A wider team of researchers, however, would have provided a wider forum for comparing different readings of the students’ reflections. It is hoped that by providing the verbatim texts and participant references in reporting the findings, the reader can also check the veracity of the findings.

The formal texts analysed in this study were only one of several modalities the participants used to document or report their understanding. Another study investigating the aesthetic outputs of participants [

22] provides an alternative perspective on the way the student teachers negotiated their understanding and navigated their pathway through the course. The findings from that study highlight the dynamic responsiveness and personal responsibility of the participants, as well as the way different modalities mediate the development and demonstration of understanding. As essays, however, are conventional and often assessed formats in higher education, this study anticipated that participants would seek to present their ‘best’ understanding through essays. While this choice of data limits the breadth of the dataset, arguably the dogma of the pedagogical statements is an attempt to meet the perceived requirements of formal education, reiterating the dilemma of opening up the space of teacher education as an ongoing dialogue that invites participation.

Another limitation of this study could be the particular conditions of the IP. While the appended programme and evocative report provide insights into how the IP was realised, it cannot be repeated. No experience, however, is repeatable, yet this does not mean we cannot learn from experience; indeed, the sharing of experience is an important way to continue with our navigations and negotiations within education [

15,

56]. Moreover, it is perhaps short-sighted to think that educators can ever be fully prepared to deal with emergencies, but they can be prepared to fully anticipate contradictions [

39], questions, and dilemmas [

36] as responsible, ecocentric educators [

28,

38]. This is a challenge that mainstream teacher education needs to address as the longer timeframe provides greater opportunities for deepening and enriching reflective dispositions than a 10-day programme can afford.

5.2. Future Research

For future research, one avenue would be to examine how student teachers engage with course readings, that is, the voices of authorities, as they build their understanding, whether student teachers can be encouraged or enabled to enter into dialogue with more authoritative others, open to learning without minimising oneself, and on the other hand to engage with the stories of concrete others, that is children, students, and families that have endured crises and have experiences to share. This would perhaps be one way of sustaining dialogue as a feature of pedagogical understanding, rather than a finalizable achievement [

62,

63]. This study offers a novel methodological approach exemplifying how a dialogic lens is sensitive to the complexity of reflecting on pedagogical understanding from the inside as student teachers as well as from the outside as researchers. This dialogical perspective arguably has far more to offer in the development of educational research that is aware of the significant challenges and changes that are part of educational communities.