2. Māori Oral Traditions and Pedagogical Practices

Before British settlers arrived in New Zealand in the early 19th century, traditional Māori society was entirely oral in nature [

10]. Knowledge, customs, skills, practices, values, and history were transmitted among generations orally [

11]. More specifically, songs, storytelling, and chants, in particular about the past, were some of the methods used to teach children about the world around them, which included lessons about times past and those to come. [

12] contends that oral traditions and narratives “contain the sum total of past human experience and explain the how and why of present day conditions” (p. 11). His contention applies accurately to traditional Māori society, where oral traditions have long been, and continue to be, both a repository for historical knowledge and a means by which intergenerational knowledge transfer occurs [

13].

Moon [

14] argues that the oral traditions in pre-European Māori society had significant cultural and social implications, impacting not only the way in which knowledge was transmitted and stored, but also determining who in Māori communities took on the role of holding and passing knowledge from one generation to the next. Traditional Māori society was organised into a series of structures, those being whānau (families), hapū (tribe), and iwi (extended tribe) [

15]. Families were the smallest of the three kin groups and were made up of three or four generations of people, approximately 30 people in total. The main function of the family, as in many cultural groups, was the procreation, education, and general nurturing of children [

16]. Metge [

17] notes that the family provided children with their early education, teaching them about genealogy, language, tribal history, customs, and acceptable behaviour, using songs, chants, and storytelling to do so. Extended family members also played a role in teaching children, often taking responsibility in singling out particular skills and aptitude in children and fostering these skills by encouraging children to learn through play and mimicking elders [

18].

Metge [

17] observes that as children in traditional Māori society grew older, they spent less time playing, instead devoting their time to assisting their parents and learning the roles and responsibilities associated with their gender or the position in the family. Regular practice of various skills, and exposure to tribal knowledge associated with those skills, was a key learning approach in traditional tribal contexts [

19]. To support this learning, elders in the family composed songs or chants that documented historical figures and events, or reiterated traditional beliefs and political alliances, singing these near the children so the children gained the knowledge contained within the compositions [

20].

In contemporary times, little has changed regarding the influence of families on children’s learning and development, and this includes familial shaping of children’s early literacy skills [

2,

6,

21,

22]. On a daily basis, children are presented with opportunities to strengthen their early literacy skills in a range of settings, including in their homes [

23]. In fact, language and literacy are typically first encountered at home [

24], and the practices and beliefs in this home environment related to early literacy play a key role in the development of children’s literacy. Numerous studies document, in particular, the influence that shared book reading, conversations, telling stories, singing songs, and playing games within families can have on strengthening children’s emerging literacy [

2,

25,

26]. In essence, when families read with young children and engage them in literacy and language activities in a supportive manner and environment, children’s early literacy skills are more likely to be well developed [

2,

6,

21,

27].

Alongside the ongoing influence of families on children’s learning, aspects of Māori oral traditions also remain in contemporary times, such as whaikōrero (formal oratory), karanga (welcome call), mōteatea (traditional chant), haka (war chant), waiata ringa (action song), karakia (incantation or prayer), whakataukī (proverb), the telling of pūrakau (stories or legends), and creation narratives [

28]. Additionally, Reese and Neha [

29] note the importance of reminiscing about the past in Māori culture and that it is an activity that still occurs among both younger and older generations. Conversations about the past are evidence that remnants of Māori oral traditions continue to be practiced in modern times, and these conversations serve two main purposes. Firstly, they connect children to oral narratives and the lessons or messages embedded in those stories, and secondly, they provide children with an opportunity to ‘tell a story’ by reporting on an event or a tale that occurred in the past [

9].

In summary, Māori oral traditions emerged and developed over generations in an environment that relied solely on these traditions to store, communicate, and transmit knowledge and learning. However, the arrival of the written word in the early 19th century brought significant changes to Māori society. New settlers, predominantly from Britain, began to arrive in New Zealand in 1814, and their numbers slowly increased in the 1820s and 1830s [

30]. The settlers brought with them a variety of different technologies and skills, such as agricultural tools and household items, including new ways to store knowledge, specifically by using the written word. Literacy, in this case referring to the written word, had a profound effect on Māori society, and Māori actively embraced print culture, reading, and books [

31]. This led to social changes, where prestige shifted from those who were skilled orators to those who were able to read and write [

14].

During this period of social, political, economic, and technological change, learning that occurred in schools made its way into communities. The more literate that Māori became, the more their perceptions and knowledge expanded, and the broader their horizons became due to reading, the higher the demand for written materials became (Derby, 2021). O’Regan comments on Māori enthusiasm for literacy, stating:

There is usually genuine surprise and shock when I start to introduce the history of Māori literacy prowess… with the Māori newspapers and proportionately higher rates of literacy at the turn of the [20th] century than non-Māori. Over 95 per cent of my academic and professional audiences are usually completely unaware of the fact that Māori have such a literary heritage [

32].

The richness of Māori engagement with literacy discussed by O’Regan were supported by Haami [

33], who poses a counter-argument to the modern-day notion that “reading and writing [were] Pākehā [New Zealanders of predominantly British descent] things that Māori weren’t interested in and didn’t need” (p. 9). Instead, Haami argues that Māori “enthusiastically… utilised and adapted literacy for their own purposes…. Reading and writing is not exclusively for Pākehā but has… been entrenched in Māori society for over a century” (p. 10). A full survey of the interactions Māori had with literacy and their impact on Māori society is beyond the scope of this article. However, it is important to note the swift and enthusiastic adoption of literacy by Māori in light of contemporary claims that to teach literacy to Māori children is a form of neo-colonisation, or to perform well in literacy as a Māori child is to compromise one’s identity as Māori [

11,

34]. The premise of such claims is at odds with historical evidence to the contrary, and is a deficit, dangerous, and wholly inaccurate claim to make about contemporary Māori learners.

The intentions of this section were to describe the oral nature of Māori society and the methods used to teach children in traditional times. These practices, specifically singing songs, reciting chants, telling stories, and talking about the past, were then woven into an early literacy intervention, which was trialled with Māori preschool children and their families, in order to determine the effect of traditional Māori practices on key cognitive skills associated with early literacy development. In light of the central role families played in fostering children’s learning in traditional Māori society, in keeping with this pedagogical approach, the intervention was trialled with families in the home, rather than in an early childhood setting. The following section explains the intervention, from conception to implementation.

3. The Study

3.1. Key Cognitive Skills Associated with Early Literacy

It has been noted that the primary goal of the study was to explore the efficacy of a culturally responsive, home-based literacy intervention in advancing preschool children’s early literacy skills. In particular, the key cognitive skills considered were phonological awareness, which some scholars argue is the single best predictor of later literacy skills [

35,

36,

37] and vocabulary knowledge, which plays a crucial role in children’s literacy development [

38,

39], particularly reading comprehension. While phonological awareness skills enable children to decode a text, this on its own is not enough. Children also need to comprehend the content of the text in order to draw meaning from it, and this ability is reliant on familiarity with the meaning of words [

40]. Additionally, there is an interdependent relationship between phonological awareness and vocabulary knowledge, with evidence suggesting that children with larger vocabularies are more likely to have stronger phonological awareness skills [

41,

42,

43]. Champion et al. [

41] argue that as children’s vocabulary knowledge grows, the need to identify differences between similar sounding words increases. This need leads to increasingly segmented lexical representations, and children must employ their skills in phonological awareness in order to differentiate between similar-sounding words. Story comprehension and retell skills were also considered in the intervention [

9], but will not be discussed in the context of this article.

Notably, findings from numerous studies indicate that shared book reading and dialogic conversations with children that include activities such as reminiscing about past events, asking open-ended questions, singing songs, reciting rhymes, telling stories, and playing games serve to foster early literacy skills, such as phonological awareness and vocabulary knowledge [

21,

27,

44,

45,

46]. Also of note is that family practices, including those outlined above, support the growth of children’s vocabulary knowledge and phonological awareness skills [

2,

47]. Weigel [

27] contend that families who read and write regularly are more likely to have larger vocabularies, and they use these wide range of words while their children are present. Furthermore, they argue that children who observe members of their family reading books and other written material are more likely to ask questions about the materials, and to acquire a richer set of vocabulary and greater ability to discern between different words as a result of these interactions. The contentions outlined in this section were of relevance in this study because the study specifically explored any changes to early literacy skills as a result of the intervention trialled with the children and their families.

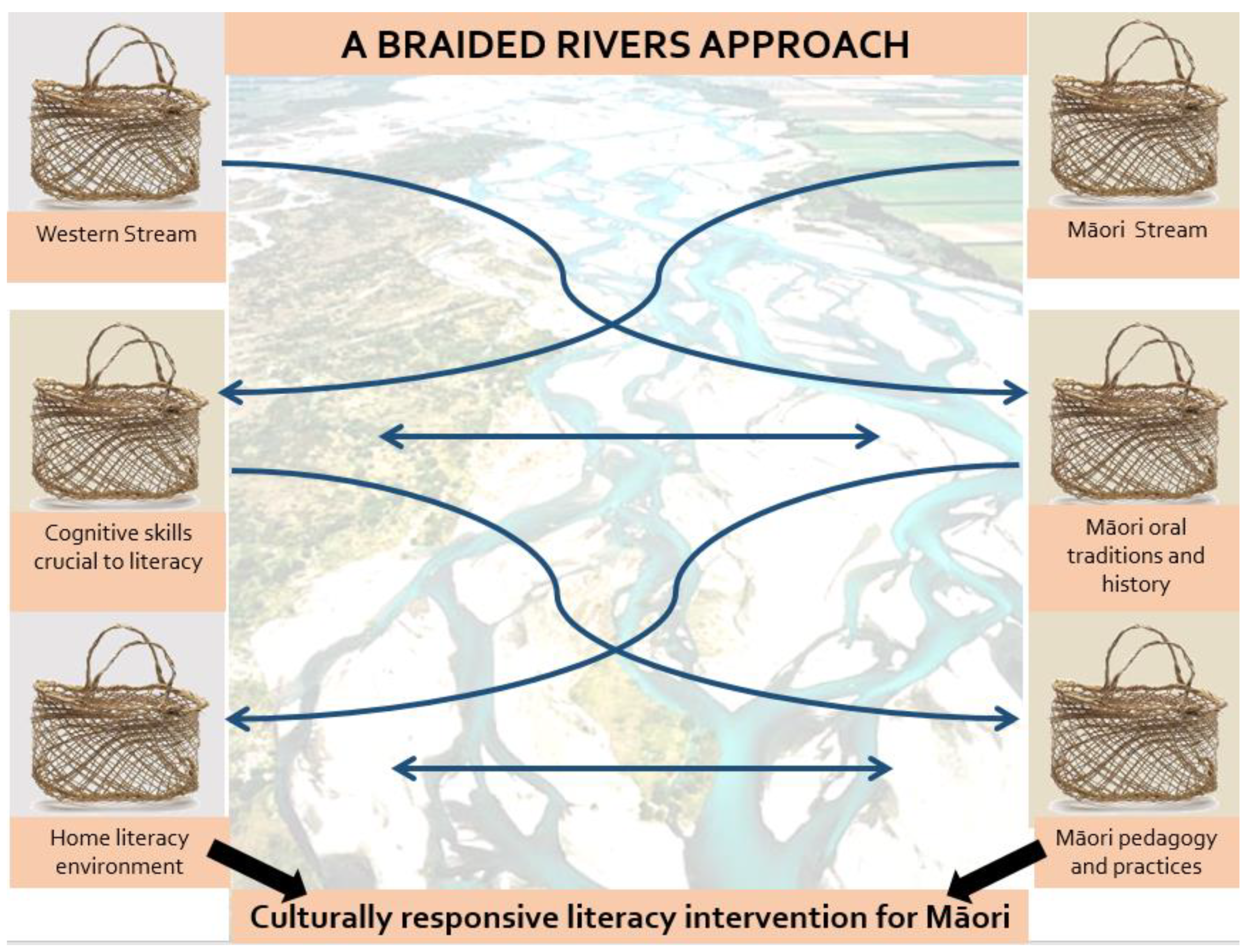

3.2. He Awa Whiria Framework

The He Awa Whiria framework was applied to adapt the intervention from

Tender Shoots [

8]. The framework draws inspiration from Indigenous and Western streams of knowledge, with Macfarlane et al. [

48] proposing that:

Western knowledge and theory, although fundamentally sound, are culturally bound, and are therefore not able to be transferred directly into another (Indigenous Māori) culture. It is therefore necessary to make a plea for an interdependent and innovative theoretical space where the two streams of knowledge are able to blend and interact, and in doing so, facilitate greater sociocultural understanding and better outcomes for Indigenous individuals or groups. (p. 52)

Essentially, Macfarlane et al. argue that a blending of Indigenous and Western bodies of knowledge results in an approach to research that is more powerful than either knowledge stream is able to produce on its own. The framework and how it was applied in the context of this study is depicted in

Figure 1 below.

The baskets under the Western stream represent research concerning the cognitive skills associated with early literacy, including phonological awareness and vocabulary knowledge and the influence of the home literacy environment on children’s literacy development. The baskets under the Māori stream represent Māori oral traditions and history with literacy, as well as traditional pedagogical approaches and practices. This framework guided the adaptation of the intervention from Tender Shoots, and resulted in a culturally responsive literacy intervention that was trialled with eight bilingual Māori preschool children and their families.

3.3. Tender Shoots and He Poutama Mātauranga

It has been mentioned that the intervention trialled in this study was adapted from Tender Shoots, which has two components: Strengthening Sound Sensitivity (SSS), which aims to enhance children’s phonological awareness abilities, and Rich Reading and Reminiscing (RRR), which focuses on developing vocabulary knowledge and story comprehension and retell skills. RRR encourages a move away from an ‘adult reads, child listens’ approach to storytelling and instead proposes an interactive style that turns a storybook into a conversation between the child and the person reading the story. This method helps children to learn new vocabulary, to understand connections between events, to better understand their emotions, and to tell better stories themselves. SSS promotes families pointing out and playing with the sounds in words during shared book reading. This helps children understand that words are made up of smaller units of sound, which can be manipulated to form other words, thus stimulating their phonological awareness skills.

With its focus on conversations and storytelling practices that occur within families, the researcher identified the resonance

Tender Shoots had with Māori pedagogy and oral traditions. The researcher applied the

Cultural Enhancement Framework [

49], which is a tool used to adapt interventions for use with Māori. The new version of the intervention was named

He Poutama Mātauranga to reflect the oral tradition in which one of the gods in the Māori creation narrative, Tāne-o-te-Wānanga, ascended to the uppermost heavenly realm in his quest for superior knowledge. In this narrative, Tāne, who, in the creation narrative, is said to be the progenitor of humankind, the forests, and all the creatures of the forest, rose through the twelve heavens to the highest realm and acquired the three baskets of knowledge named Te Kete Tuauri, Te Kete Tuatea, and Te Kete Aronui. It is said that Tāne then returned to Earth with the knowledge, and, once there, created humankind from the Earth [

16]. A ‘poutama’ is a stepped pattern that symbolises both genealogy and various levels of learning and progression [

50]. ‘Mātauranga’ in this context is best interpreted as knowledge, wisdom, understanding, and skill [

50]. Therefore,

He Poutama Mātauranga reflects a quest for knowledge and captures the cumulative, progressive nature of the skills the intervention aims to promote.

3.4. The Research Setting and Participants

The early childhood centre involved in the study was Nōku Te Ao, which is located in Christchurch, New Zealand. It provides early childhood education to children aged 0–5 years. Nōku Te Ao, which means ‘the world is mine’, granted permission to use their name in publications. They are classified as a dual language centre, meaning the teachers engage with the children in both English and Māori. The participants involved in the study were four-year-old Māori children attending Nōku Te Ao and their families. The two criteria for selection were that children were four years of age for the duration of the 12-week intervention, and that they attend Nōku Te Ao. The centre manager extended an invitation to participate in the study to families who had a four-year-old child attending Nōku Te Ao. Eight families in total agreed to take part in the study, with the final cohort of participants comprising two boys and six girls. Data collected during pre-intervention interviews with the mother of each child indicated that every child started at Nōku Te Ao at age two years old or younger, and none of the children presented with any medical challenges at the time of the study or at birth. Each mother had beginner to intermediate levels of reading and speaking in the Māori language, but English was by far the dominant language for all of the children. The vast majority of them were exposed to English in the home for 80 percent of the time or more. Three of the children heard or spoke a third language in their home, those languages being Tongan, Japanese, and Samoan.

3.5. Research Design

Due to the relatively small number of participants in the study, a single case design was deemed to be the most suitable [

51]. This design meant each child acted as their own control, which meant stronger conclusions were able to be drawn from the findings. The single case design sought to gain insight into three things:

1. Whether there was an observable and important change in the dependent variables (phonological awareness and vocabulary knowledge);

2. Whether the observed change in the dependent variables post-intervention was a result of the application of the independent variable, where the intervention was the independent variable in the study;

3. Whether this change is something that is able to be generalised across time, setting, and target.

As mentioned above, the study also utilised a crossover design. The eight participants were split into two groups of four and were randomly assigned to the intervention sequence. One group completed the RRR portion first, which ran for six weeks, while the other group completed the SSS component, which also ran for six weeks. The groups switched at the midway point of the intervention, which then ran for a further six weeks. This feature of the research design established another control in the study [

52] and allowed comparisons to be made between the two groups on the basis of the nature and timing of their engagement with the intervention, thus increasing the rigour of the findings.

3.6. The Intervention

Prior to the intervention commencing, families who had agreed to take part in the study were invited to participate in either an RRR or an SSS workshop, both of which would explain how to conduct the activities associated with each component of the intervention. Each workshop ran for approximately two hours and followed the same format of a PowerPoint presentation with time for questions, although the content differed depending on whether the focus of the workshop was RRR or SSS. The presentation essentially outlined why RRR or SSS is important in cultivating strong language skills in preschool children and how families were to engage with and record the activities they completed during the intervention. Following the workshop presentation, families were given the opportunity to ask questions. Finally, at the end of each workshop, they were provided with tip sheets to take home to remind them of key points covered in the workshops.

The researcher created resources to support the activities included in the intervention, and sourced 24 children’s books, 12 of which were allocated to the RRR portion of the intervention. These books were chosen for RRR because they were stories about events to which children could relate with ease, such as going on a picnic or visiting extended family. The remaining 12 books supported the SSS-focused activities and were selected due to their use of rhyme and/or alliteration in the text. For a full list of the books used in the intervention, see [

9]. After the families had completed the instructional workshops, the researcher gave two storybooks to each family per week for six weeks, one in English and one in Māori. They were asked to read either book, or both books, three times each over the course of the week. During each reading, they were required to read a series of sticker prompts strategically placed by the researcher throughout the book. Two examples of sticker prompts are ‘Can you find something on this page that rhymes with ‘boat’’ and ‘What does ‘burrow’ mean?’. The researcher recorded how many readings were completed by the families using a reading chart, which was stamped by the child after each reading or activity was completed (see [

9] to view the chart). This chart also allowed the researcher to see whether families were using more English, more Māori, or a mixture of both languages during the intervention. Families provided the completed charts to the researcher at the end of the intervention.

The sticker prompts created for each book, which families were asked to read aloud when they read the book with their child, had questions or statements on them, which became incrementally more difficult with each reading. The prompts in the books that aligned to the RRR workshops were related to understanding the story, learning new words, understanding emotions, and connecting the story to the world around them. The prompts in the books that aligned to the SSS workshops attempted to foster skills in hearing the sounds in words, particularly syllables in words, sounds that rhyme, and the initial phoneme of a word.

In addition to this, families completed activities each week, which drew from traditional Māori pedagogical practices mentioned at the outset of this article, and included singing songs, playing games, having interactive conversations, and reminiscing about the past with their children. The activities included in the RRR component of the intervention encouraged families to ask open-ended questions about the book they read as well as outings they had that were similar to those in the book, explain the meanings of new words, reminisce about the past, and make connections with the child’s world. The books and activities utilised in the SSS portion of the intervention focused on stimulating children’s ability to detect the sounds in words—in particular, words that rhyme, the initial phoneme of a word, and manipulating the sounds in words.

3.7. Data Collection

As mentioned, both the RRR and SSS components of the intervention were conducted for six weeks each. Using game-based assessments, data were collected prior to the intervention beginning, referred to in the study as ‘pre-intervention’, in order to establish a baseline against which to measure any subsequent change in children’s phonological awareness skills and vocabulary knowledge. There was a two-week break between the group changeover, and at this point, further data sets were gathered so as to determine any shifts that may have occurred as a result of the RRR and SSS activities. This point in the research is referred to in this article as ‘mid-intervention’. Following the mid-intervention break, the groups switched and completed the other portion of the intervention. Data sets were gathered at the conclusion of the intervention, referred as ‘post-intervention’, as well as six months after the intervention had ceased. This final data collection aimed to capture whether any changes in children’s early literacy skills were sustained over a longer period of time.

During the four sessions of data collection, children were asked to identify initial phonemes in both English and Māori words, to syllabify English and Māori words by clapping the number of syllables in each word, and to name a series of objects by completing a picture naming task. At each data collection point, three repeated measures of the initial phoneme identification tasks and the syllabification tasks were taken pre- and post-intervention, and two were carried out mid-intervention. This method produced an average score for each child and allowed for greater insight into children’s capabilities at that point in time. Children were asked the questions related to the picture-naming task once during each round of data collection.

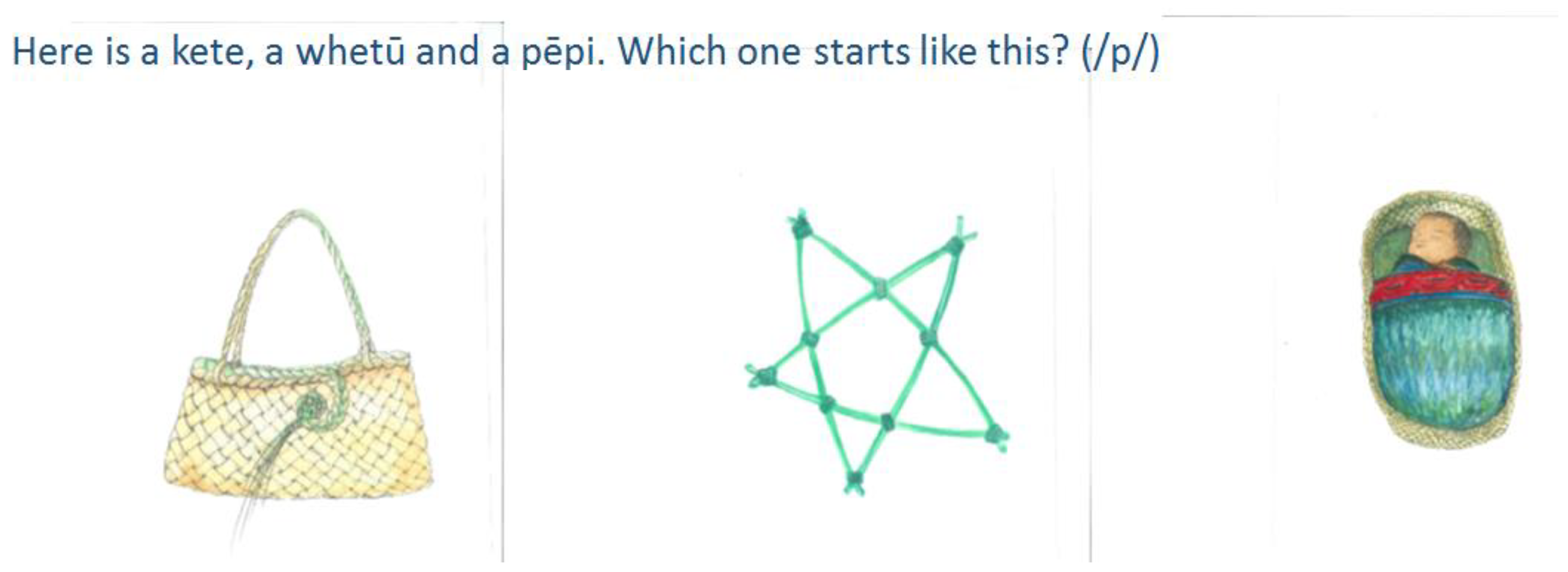

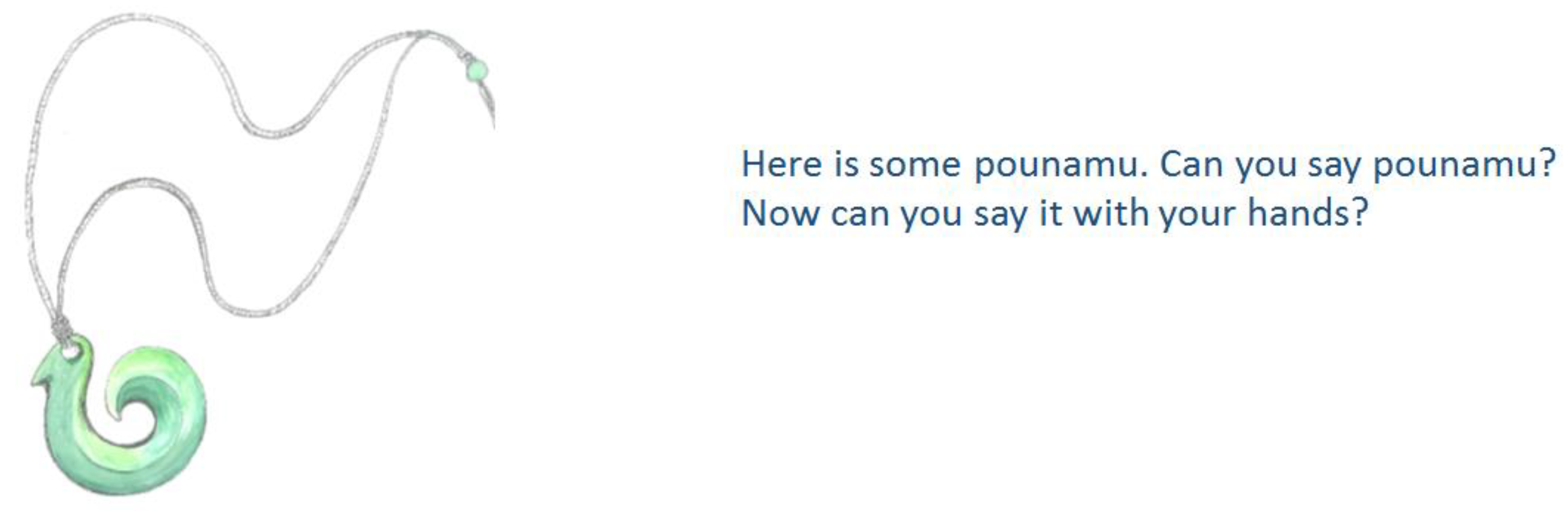

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 below provide examples of a Māori language initial phoneme identification question and a Māori language syllabification question, respectively.

For the picture naming task, children were shown an image from a storybook used in the intervention and were asked to name what the image depicted.

3.8. Analysis and Results

The study drew from analysis methods used in replication design [

53]. Yin [

54] argues that replication of a study across single cases (in this instance, N = 8) produces patterns, which can be taken as evidence of a general phenomenon and from which solid conclusions can be drawn. For case study analysis, including single case design, Trochim [

55] states that what he refers to as ‘pattern-matching logic’ is one of the most rigorous techniques to employ in order to analyse and interpret data, such as those sets gathered in this study.

More specifically, data relating to the phonological awareness skills of each child were analysed and statistically validated using a two-standard-deviation band method [

56]. These results were plotted on a graph for each child and for each portion of the intervention, in both languages [

2]. The crossover design revealed that it was only after each child had completed the SSS portion of the intervention were they able to identify initial phonemes in English and Māori words and identify the number of syllables in English and Māori words, at a rate that was significantly above chance. In other words, the children were not simply guessing the correct answer but rather were able to draw on their skills in phonological awareness and use these to identify the right response to each question. All the children, irrespective of the sequence in which they completed the intervention, improved to a point that was significantly above chance, thus allowing conclusions to be drawn about the positive shifts that occurred in their phonological awareness skills as a result of the intervention [

9].

The data gathered using the picture naming task, which revealed any changes to vocabulary knowledge, were analysed by comparing the mid- and post-intervention results with those gathered pre-intervention. Each child scored 0 out of 8 pre-intervention, but after completing the RRR portion of the intervention, which focused specifically on expanding children’s vocabulary, children were able to name an average of 4 out of 8 new words. Again, the crossover design allowed conclusions to be made about the effects of each component of the intervention on the specific skills they targeted, as well as on the impact of the intervention as a whole on children’s early literacy skills.

Crucially, all the children maintained, or in some cases, further improved, their skills in phonological awareness and vocabulary knowledge six months after the intervention ceased.

4. Discussion

It was mentioned at the outset of this article that the overarching intention of the study was to explore the effects of a home-based literacy intervention on children’s early literacy skills. This article specifically highlights the role that Māori oral traditions and pedagogical practices, the latter of which include singing songs, reciting chants, telling stories, and reminiscing about the past, can have in supporting children’s early learning in the contemporary era, as these practices did in traditional times. In particular, the effects of Māori oral traditions and pedagogy on key cognitive skills associated with children’s early literacy development, those being phonological awareness and vocabulary knowledge, were considered.

In the opening sections of this article, Māori oral traditions and pedagogical practices were described. The wholly oral nature of traditional Māori society—in particular the significant role that storytelling, songs, chants, and an awareness and sharing of the past played in passing knowledge from generation to generation—was used to inform the development of a culturally responsive literacy intervention, adapted from Tender Shoots. The newly created intervention, with its focus on engaging children in interactive conversations, storytelling, singing songs, reciting chants, and reminiscing about the past, was grounded in Māori oral traditions and pedagogy, and in particular, reflected the premise that talk and discussion were effective methods used to teach children about the world around them—learning that was subsequently passed from generation to generation in oral form through the centuries.

Overall, the intervention, which was trialled with bilingual Māori preschool children and their families, had a significant positive shift on fundamental cognitive skills that support children’s early literacy development. Each child in the study, after completing the SSS portion of the intervention, had stronger phonological awareness skills and, it has been noted, maintained these improvements six months after the intervention ceased. In fact, the crossover design of the study revealed that it was only after completing the SSS portion of the intervention that positive shifts were made in children’s phonological awareness skills. In other words, at the mid-intervention data collection round, the phonological awareness skills of the children who completed the RRR portion of the intervention first remained unchanged from their baseline scores, thus allowing strong conclusions to be drawn about the effects of the activities included in the SSS portion of the intervention on children’s phonological awareness skills.

The same pattern emerged for the cohort that completed the RRR component of the intervention first, with their vocabulary knowledge showing improvement at the mid-intervention data collection point, whereas the cohort who engaged in the SSS portion of the intervention first demonstrated no expansion of their vocabulary knowledge from pre-intervention scores. Again, this pattern allowed for solid conclusions to be made about the effects of the RRR portion of the intervention on children’s vocabulary knowledge. In addition to this finding, irrespective of the order in which the children completed each component of the intervention, all the children expanded their vocabulary knowledge as a result of the RRR portion of the intervention, and again, these gains were sustained six months after the children and their families completed the intervention.

Crucially, families discussed other changes in the children as a result of the intervention, noting that the children were more likely to ask what new words mean, had improved listening skills, were more inclined to ask questions during shared book reading, and were more engaged in their learning overall. Despite the smaller number in this pilot study, which could be interpreted as a limitation of this work, the methods used here were well received by families and provided strong and conclusive data sets needed by the researcher to answer the research questions. Further studies employing these methods, but possibly of longer duration and with a broader focus, would reveal subsequent shifts in children’s learner identity and self-efficacy as a result of the intervention. Certainly, these preliminary findings bode well and support the need for further investigation of the influence of the intervention on these critical learner attributes and practices.

Finally, in traditional Māori society, the family unit played a pivotal role in fostering children’s learning, and, in order to align the intervention with this pedagogical approach, the intervention was trialled in the home with families leading it, as opposed to with teachers in an early childhood setting. The findings revealed that, just as it was in traditional times, the families involved in the study had a significant impact on children’s early learning—in this case, specifically fostering children’s foundational literacy skills. In addition to this, families reported that they embedded many of the strategies employed in the intervention after the intervention had ceased, which indicates not only the sustainable nature of the strategies used but also the commitment each family has to its child’s learning. Ultimately, these findings lend weight to the importance of involving families in children’s learning and in fostering strong partnerships between the home and school or early learning environments. The findings in this study demonstrate that families are willing and able to play a crucial role in supporting their children’s learning.

5. Conclusions

Children’s literature and the arts have long supported children’s early learning and development, both in various cultural contexts and in different historical eras. The findings presented in this article, which were produced in a study that explored the role of traditional Māori pedagogy and practices on key cognitive skills associated with bilingual Māori preschool children’s early literacy development, reveal that practices from the arts, such as storytelling, singing songs, and reciting chants, play an integral role in fostering foundational literacy skills, specifically phonological awareness and vocabulary knowledge. The findings also illustrate the impact that Māori oral traditions and pedagogical approaches and practices can have on supporting children’s learning in contemporary times. These approaches and practices include the central role that families play in teaching children, as well as the effect of singing songs, telling stories, reciting chants, and reminiscing about the past on children’s early literacy skills. As an aside, but allied with the main arguments in this article, a crucial point alluded to in this work was the historical interactions of Māori with literacy, and in particular, the swift and enthusiastic adoption of this new skill by Māori in 19th century New Zealand. Alarmingly, there is a school of thought that contends that to be concerned with Māori children’s literacy acquisition and outcomes in contemporary New Zealand is a form of neo-colonisation. However, such contentions are resoundingly debunked upon examination of the historical evidence and the actions of previous generations of Māori with regards to literacy—a skill which was highly valued by Māori and ought to remain so (and indeed in most quarters remains of immense value) in the 21st century and beyond. In closing, to reiterate the central argument in this work, children’s literature and the arts—in the context of this study in the form of traditional Māori pedagogy and oral narratives—have played, and continue to play, a crucial role in supporting children’s early learning and in fostering strong connections to the world in which we live.