Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a dramatic effect on society, including teaching within higher education that was forced to adapt to online teaching. Research on this phenomenon has looked at pedagogical methods as well as student perceptions of this way of teaching. However, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have looked at the wider perspective, within the entire student populous of a university, what students’ perceptions are and how these correlate with the students’ previous experiences and habits with online platforms, e.g., online streaming or social media. In this study, we perform a questionnaire survey with 431 responses with students from 20 programs at Blekinge Institute of technology. The survey responses are analyzed using descriptive statistics and qualitative analysis to draw its conclusions. Results show that there is no correlation between previous habits and student experience with online platforms in relation to online learning. Instead, other factors, e.g., teacher engagement, is found central for student learning and therefore important to consider for future research and development of online teaching methodologies.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has had significant impact on the ways in which higher education institutions deliver their education provision [1]. The sudden shift from traditional learning to online learning in the spring of 2020 had a major impact on academics and on many higher education students as their academic studies were radically changed. The challenges faced by both teachers and students in the context of emergency remote teaching include social, educational, psychological and technical aspects as teachers and students both had to rethink their roles and ways in which to organize and carry out their work and their studies [2,3,4]. While the rapid shift to digital forms of teaching and learning was challenging in many ways, both positive and negative perspectives have been highlighted internationally.

As we are now transgressing to what has been termed “the new normal” [5,6] in a post-pandemic setting, where pedagogy and technologies must be balanced in new ways, it is important to keep in mind that well-planned online learning experiences are different from courses offered online in response to a crisis or disaster. Colleges and universities working to maintain instruction during the pandemic should understand those differences when evaluating emergency remote teaching. At the same time, we must learn from the experiences of unplanned and forced versions of online learning and teaching to bridge the gap between online teaching and campus learning in the years to come. The pandemic has called for innovative adaptations that can be used for the digital transformation of higher education institutions by building on the empirical evidence accumulated during this period of crisis. A literary review of papers reveals that the emergency remote teaching during the pandemic can indeed give way to a more long-term integration of physical and digital tools and methods that can sustain a more active, flexible and meaningful learning environment [7]. Understanding how students perceive the learning environment and learning process is important as it both affects student engagement and helps educators rethink the principles of learning [8]. However, in exploring studies on student experiences with online learning during the pandemic we saw that a majority focused on specific student groups or study programs. The few cross-sectional studies that we found also focused on a specific student groups, such as e.g., medical students at various universities [9].

The motivation behind this study is two-fold. First, we wanted to see if there are detectable variations between students with different experiences of online use across subject fields and study programs at one higher education institute. Second, the understanding how students with different online platform experiences and habits experience online learning may result in the identification of specific pedagogical challenges and possible means of quality improvement across the university. As such, the study is based on an underlying assumption that previous experience and perceptions of online platforms for leisure (e.g., Facebook and YouTube) have an influence on students’ experiences and perceptions of platforms for online learning.

The study was carried out in the latter part of the pandemic, when it could be argued that emergency remote teaching had merged closer to what is generally referred to as online learning. We can thus discern some of the lasting traces that the pandemic left as we discuss the question how to plan our teaching and learning environment in a post-pandemic educational environment.

2. Related Work

The integration of online and face-to-face instruction is historically been referred to as blended learning [8]. As we have discussed in a previous article [10], although the term was coined in the late 1990s [11] there is still a lack of a shared blended learning terminology. Hrasinski has even characterized the discourse on blended learning as ”pre-paradigmatic, searching for generally acknowledged definitions and ways of conducting research and practice” while urging for the need for established and clear definitions and conceptualizations [12]. As we have pointed out, however, the variety of proposed blended learning models find common ground in the ingredients of face-to-face and online instruction or learning [10,13,14]. Face-to-face instruction is here synonymous with the traditional classroom setting, where teacher and students interact in a physical learning space [6].

With online learning, also referred to as distance learning and e-learning, access to a learning environment is achieved through a computer (or mobile media) mediated via the internet [15,16]. Online education today uses technology platforms such as Zoom, Microsoft Teams and Adobe Connect to provide a video conferencing experience [17,18]. Along the same line as our previous article [10], we follow a broad definition of blended learning and use the terms online learning, distance learning and e-learning interchangeably [19]. While some researchers and practitioners distinguish between these terms, for others they carry the same meaning. We further suggest that online learning changes the components of teaching and learning which require specific considerations, such as the need for a higher involvement on behalf of both academics and students, a higher social online presence, and a series of personal characteristics [20].

As stated above, both positive and negative perspectives have been highlighted internationally with regards to online learning in the wake of the pandemic [21]. Feedback from teachers is one important aspect that has been considered from both positive and negative viewpoints [22]. A scoping review that synthesizes and describes research related to online learning interventions in six disciplines across six continents, focusing on technological outcomes in higher education, shows that digital formats of learning were seen as both effective, resource-saving and participatory forms of learning in a majority of the articles [22]. Students especially appreciated the self-paced learning and many found a greater motivation to learn. Other studies show that students appreciated the flexibility that online learning provides [23]. On a similar note, a study from France shows that learners liked the possibility of re-playing lectures [24] and a survey among STEM students experiences with the COVID pandemic and online learning shows that a majority enjoyed the convenience and flexibility of online learning [25].

While much could be said about the positive aspects of online learning, a sizeable body of research indicate negative academic outcomes among students in online courses as opposed to campus courses [26,27,28,29]. Students in online courses have lower rates of course completion and grades and tend to be less persistent and motivated to finish [30]. Among the reasons raised, procrastination is a key issue [31]. While psychosocial challenges have received much attention in the academic field, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, technical challenges in using the digital devices or platforms are also common [32]. Technical difficulties was a central result in a cross-sectional study among Malaysian medical students [33], while others considered the effects of technologies in a more nuanced manner, considering various specific factors. Interestingly, a study from two of Romania’s largest universities shows that the advantages of online learning identified in other studies seem to diminish in value, while disadvantages become more prominent [32].

A growing body of research on online learning reinforces the potential negative impacts that an abrupt shift to online courses could have on students’ academic performance. Well-planned online learning experiences are claimed to be “meaningfully different” from online courses offered is response to an emergency or crisis [34]. Increased levels of anxiety and stress for both teachers and students [35] are underlying factors. Piaget’s rationale that effective factors have a major impact on the cognitive process supports this line of argumentation. While the pandemic forced emergency changes with raised levels of anxiety and stress, studies show that online learning and the new technologies and teaching strategies that emerged can continue to be used in a post-pandemic setting [36,37]. Among these we find student response technologies, which are used to increase students’ engagement [38,39].

In pondering the question of how to maintain and develop teaching strategies in a post-pandemic setting, it is important to understand how students perceive the learning environment and learning process and its connection to student motivation and engagement [8]. While most studies tend to focus on the here and now, which includes issues such as teacher visibility, feedback and challenges related to psychosocial and technical matters, a smaller body of research focuses on how student experience with online platforms affect their experience of the online learning setting. As noted in the introduction, however, a majority of the studies of online learning focus on target student groups or study programs, even across universities. The cross-sectional studies that have been made during the COVID-19 pandemic rarely include all students across one particular university. One of the biggest studies made on online experiences among students focuses on understanding the characteristics of online learning experiences among Chinese undergraduate medical students [9]. As the authors investigate students’ perceptions of online education developed in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in relation to prior online learning experience they find a significant positive correlation. Another result is that this correlation decreases in significance the higher the students are in their learning phases. In a similar fashion as our study, the authors collected data using an online survey albeit with a significantly higher number of students (the questionnaire was sent to 225,329 students, of whom 52.38 (118,080/225,329) replied, with valid data available for 44.18.

In this study we wanted to see if we could detect variations between students with different experiences of online use across subject fields and study programs at one higher education institute. The study rests on the belief that it is indeed important to understand how students perceive the learning environment and learning process as it affects both student engagement and helps educators rethink the principles of learning and the ways in which we should support our students in their learning process. We hope to contribute to an understanding of how students with different online platform experiences and habits experience the online learning environment. We also hope that the results can assist in the identification of specific pedagogical challenges and possible means of improvement in the ways in which we plan our teaching and support the students in their learning process.

3. Methodology

The research study presented in this manuscript was carried out at Blekinge Institute of Technology (BTH) in Sweden. BTH is a technical university with programs that include computer science, software engineering, mechanical engineering, nursing, industrial engineering and management as well as spatial planning. Similar to most universities around the world, BTH was forced to switch to a completely online teaching mode during the COVID-19 pandemic. The study was carried out across all study programs in the spring of 2021 to get insights into the students’ experiences of this teaching reform and get insights for future online teaching.

3.1. Research Objective

In this section, we will present the research objective and detail the design that was used to collect the research results and its analysis. The objective of this work was to elicit students’ experiences with online teaching and evaluate if students from different programs experienced the teaching in different ways. To guide the research we have split up the research objective into two research questions.

- RQ1: How do students at BTH experience online teaching in terms of quality and usefulness?The rationale for this question was to gain insights, from the students, if the teaching methods that were used during the pandemic had been sufficient. The results of this analysis would provide an indicator for the current quality as well as what possible improvements, or concerns, which would be required in the future.

- RQ2: Are there differences in experience with online teaching related to subject areas?The rationale for this question is based on an underlying assumption that there would be clear differences in how different students would experience the online learning, for instance, due to previous technical experience with online platforms for streamed media. Identifying differences between groups would help teachers in finding which groups that may require additional, or different, forms of teaching in an online teaching environment.

3.2. Research Design

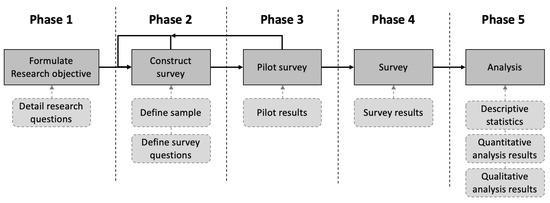

The data for this study was collected through a questionnaire survey with students at BTH. Figure 1 presents a visualization of the methodology, which was divided into five phases; formulation of research objective, construction of the survey, pilot survey, data collection and analysis. The boxes in the figure explain the activities of each phase, whilst boxes with rounded edges are the outcomes of each phase. Arrows indicate the order of activities, where back-arrows indicate redesign due to collected results.

Figure 1.

A visualization of the research methodology that was followed in this study.

In the continuation of this section, the activities and outcomes of each activity, will be detailed.

3.3. Phase 1: Formulation of Research Objective

In the first phase of the study, the research objective was defined. This was achieved through discussions among the authors as well as discussions within the faculty at BTH. The origin for the research also stemmed from a previous study, conducted by the authors, looking at student perceptions about online teaching [10]. In the previous study, the influence of prior experience with online platforms was investigated. However, this study was limited to only one class of students. In this work, this evaluation was scaled up to encompass a larger sample of the students at BTH.

Primary concerns that were discussed were based on the assumption that students with varying technical backgrounds would have different experience with the online teaching. This assumption, if true, would indicate that students also require different modes of online teaching, e.g., with varying teaching materials, tools or platforms. Furthermore, BTH recognized the value of eliciting what students’ current experiences were of existing online teaching to help give inputs for future improvements.

These objectives make the study descriptive in nature, which justifies the use of a survey. Questionnaires were chosen as the research method since the objective required an outreach to all students at the university. This made interviews an impractical data collection method due to resource constraints.

3.4. Phase 2: Construction of the Survey

The survey was constructed in an iterative manner, as indicated in Figure 1 by the back-arrow within the phase. As a first step, the sample frame [40] for the study was considered. Since the study aimed to study the research objective on a university level, the entire student body was set as the sample frame, from which a representative sample could be drawn, i.e., one-stage sampling [41]. From this sample-frame students were selected from all 20 programs at the university, from both 1st cycle—Undergraduate or bachelor’s level—and 2nd cycle—Graduate or master’s level—students [42]. However, due to surveys being a frequently used method for data elicitation at the university, we identified a risk of survey-fatigue [43]. To mitigate this threat, random sampling was used if first, second or third year (if applicable) students were selected. Whilst this approach mitigated the situation that some students were exposed to multiple surveys under a short time-span, it introduced a threat in terms of sampling-error [44]. Hence, that some groups within the sample would not be representative for their peers. However, since this random sampling was deployed over the entire sample frame, where multiple programs have shared characteristics, this threat is perceived to be low. Using this approach, a final sample of 1515 students were chosen for the study.

Once the sample had been decided, the second step of this phase was to define the survey questions. The survey was initially drafted by three of the study’s four authors, in an online word document, after which the questions were reviewed by all authors. These revisions were carried out iterative in online sessions. Before each session, all authors individually reviewed the questions and commented upon the semantics as well as syntax of the questions. These comments were then discussed, question by question. After that, the questions were updated until a consensus was met by the authors, inspired by the Delphi method [45]. This was possible due to the authors’ combined domain, survey research and pedagogical knowledge, in excess of 35 years of experience.

The focus of the reviews was primarily on the semantic meaning of each question, i.e., that they correctly captured the phenomenon of investigation. Secondly, that the syntax of each question was unambiguous, i.e., that the questions could not be interpreted in multiple ways. Through this process, the survey guide went through six iterations, after which a final draft of 18 questionnaire questions was proposed, most of which were multiple-choice or Likert-scale [46]. The drafted questions were written in Swedish, the authors’ native language, after which they were translated into English to be applicable for the entire sample. In the translation process, care was taken to pertain both the semantic meaning and syntactical non-ambiguity of the Swedish questionnaire guide.

The questionnaire guide was divided into five parts. Part 1 was a description of the study, its intent and how collected data would be used. A statement of anonymity was also given to ensure that students answered the questionnaire truthfully.

Part 2, consisting of only one question, aimed to elicit demographic data about the students’ age. We were careful not to elicit other information due to potential ethical concerns. We did not elicit what program the students belonged to because we were able to elicit this by how the questionnaire was distributed among the sample. This was achieved by using the University’s questionnaire system, Blue, which allows different surveys to be sent to different student groups. Thus allowing us to trace the answers for a specific survey with a particular group of students.

Part 3 of the questionnaire, consisted of 11 questions related to the students’ prior knowledge, experience and habits with using online media platforms, e.g., YouTube, Facebook, etc. These questions included what platforms the students’ were familiar with, how often they used them on a monthly basis, when they were introduced to online platforms, and why they used the different platforms. This was followed up with questions aimed to compare the students experiences with the platforms they use for leisure and the ones available at the university. The students’ were also asked what devices they use to view these platforms, both for leisure and education. These questions consisted of multiple-choice questions where students could either mark one or several alternatives. In addition, the questions included the option to answer “other” if the predefined answers were not sufficient.

Part 4 of the questionnaire then focused on the students’ study habits and use of available platforms, in six questions. The first of these aimed to elicit what study materials the students use, provided by a multiple-choice list where students could also add “other” materials if needed. This was followed by questions regarding the experienced quality of the education, if the quality was comparable to campus education, and if teachers did a suitable job in the online education. Next, the students were asked if they would see a perceived benefit of having the lectures subtitled. Hence, a more theoretical question, based on observations and the assumption that subtitles would be of value to student learning. In the final two questions, the students were asked if they experienced that their education has been affected by the switch to online learning and what changes/improvements they would like to be seen made to the education. The latter question was open-ended, allowing students to write their answers.

Part 5 of the questionnaire consisted of a single question where the students were allowed to give feedback on the questionnaire itself. For instance, if they found any questions ambiguous or if they felt that they wish to express some information that was not elicited by the questionnaire.

For detailed information about the questionnaire, the questionnaire guide can be found in Appendix A. A replication package with the survey answers has also been made available here:

3.5. Phase 3: Pilot Survey

To evaluate the correctness of the questionnaire guide, it was distributed in a pilot study with a sample of 226 students. Out of the 226, 96 students responded, providing a response rate [47] of 42.5 percent. Particularly, the final question was analyzed where students could provide feedback on the questionnaire itself, e.g., if any of the questions were considered ambiguous. Analysis of the feedback revealed only minor detailed improvements, which were applied by updating the wording, i.e., the syntax, of affected questions. These changes are indicated in Figure 1 by the backwards arrow from Phase 3 to Phase 2.

Since these changes did not affect the semantic meaning of the affected questions, the results of the pilot was kept to be integrated in the final dataset. Although this presents a minor threat to the validity, our analysis of the pilot results, also when compared to the results of the final survey, indicate no mayor differences. Hence, we perceive this threat to be low.

The pilot was distributed using the Blue survey tool in the same way as the final survey. Blue provides an online interface for taking the survey with multiple pages with one to several questions per page. Access to the tool was provided through an URL sent to students via e-mail. For the pilot study, only students from industrial economy and the master of business and administration programs were sampled. This sampling was motivated by the programs having a heterogeneous group of students in terms of nationality, i.e., both Swedish and international students. However, this sampling does impose a possible threat, since all students came from the economy domain and thereby have a similar background. Since the response rate was so high, and initial analysis showed a diversity in the answers, we perceive this threat to be low.

3.6. Phase 4: Data Collection

After the pilot verification and updates, the questionnaire was distributed to the full sample of 1515 students. As mentioned, to track the results from individual programs, the survey was sent via e-mail to e-mail lists for each of the 20 included programs. Thus allowing us to track the results from the individual programs.

Out of the 1515 sent requests, 431 students completed the final survey, providing a response rate of 28 percent [47]. The results were provided in comma-separated value (CSV) files but also descriptive statistics generated by the Blue tool. These outputs were used as input for the continued analysis in Phase 5.

3.7. Phase 5: Analysis

In the final phase of the methodology, the survey results were analyzed to draw conclusions to answer the study’s research questions and verify/deny the study’s assumptions. The analysis was carried out in three different activities.

In the first activity, a qualitative analysis was made of the resulting descriptive statistics provided by the Blue survey tool. This analysis was done first individually by all authors, where each author drew conclusions from the graphs. Next, the Delphi method was once more used where the individual conclusions were discussed and compared to reach a consensus.

This analysis, since it was based to the answers of individual questions, were of lower level of abstraction and thereby only contributed to answer RQ1 regarding the students’ experiences of the quality and usefulness of the online teaching at BTH. In particular, survey questions A, B, C, D and E, were analyzed during this activity.

In the second activity, formal statistics was applied together with descriptive visualization to answer RQ2 regarding the differences in experience of the online learning in different subject areas. The formal statistics were calculated using the statistical programming tool R, starting with a correlation analysis of the answers of all quantitative answers. To simplify analysis of the results, the results were plotted in a correlation matrix. Results of showed that there was no correlation between any pairs of questions in the questionnaire, implying that the student responses were heterogeneous across the sample.

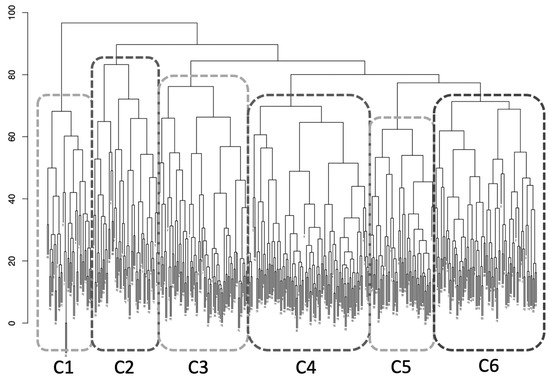

To gain deeper insights into potential sub-divisions within the data set, a cluster analysis was performed using hierarchical clustering [48] with euclidean distance of the complete data set. The result was plotted in a Dendrogram that revealed six clusters within the data set. Thus, indicating, from a semantic perspective, six sets of students with similar answers, i.e., experiences and perceptions.

To answer RQ2, these clusters were then analyzed to see if any of the clusters were populated by more students from any given program. This analysis was based on the hypothesis that if previous experience was influential in the students’ perception of online learning, there would be correlation between prior experience and students’ experiences with online learning, i.e., between responses to Part 3 and Part 4 of the questionnaire. Since the number of respondents from each program varied, the number of respondents were first normalized based on number of respondents. The normalized number of respondents in each cluster were then compared to see if students from any particular program had a higher affiliation to any one cluster. For this final analysis, students from the 20 programs were divided into their core programs, being computer science, software engineering, mechanical engineering, etc. Thus, resulting in eight main programs. In addition to looking for trends in program distribution among the clusters, we also looked at the distribution of 1st and 2nd cycle students. The analysis aimed to find if any cluster was more highly populated by students from a given cycle of students.

The results of the cluster analysis provided insights into the distribution of students from different programs which allowed us to draw conclusions to answer RQ2.

To complement the qualitative conclusions from the statistical analysis, qualitative analysis was made of the open-ended questions. This analysis was inspired by open coding [49], where the students’ statements were read and re-read, and codes generated from, or for, each statement. Each statement was considered in relation to its content, semantics, related words and phrases. When a new statement was found with similar content, it was assigned the existing code. The statements and connected codes were then re-read, searching for thematic patterns. Thus, clustering statements of similar content together. The coding resulted in eight codes/themes resulting from the analysis of 248 statements. These codes were: pedagogical/didactic improvement, technical improvements, course structure, interaction/feedback, online lectures, negative non-constructive feedback, positive non-constructive feedback and online/recorded lectures.

3.8. Threats to Validity

In this section we report on the threats to the validity of this research, including both its design and results.

Sample: The sample frame for the study was the entire student body at Blekinge Institute of Technology. However, since there was, as discussed, a risk of survey fatigue, we delimited the sample by randomly sampling only one year of students per program. Whilst this provides us with coverage over all programs, it does not provide a comprehensive view of all years of the students. This is a threat since the second and third year students had experienced both online and campus teaching, whilst first year students had only experienced online learning. However, due to the size of the sample and overlap between programs, we perceive this threat to be minor.

Furthermore, although the sample size was smaller (N = 431), this still represented a response rate of 28 percent. Hence, although the response rate could be higher, we perceive this result to be adequate for our study.

A larger threat of the sample was that first year students had only experienced the online teaching format. Thus, limiting their ability to answer questions regarding the comparison of campus and online teaching. However, these questions had an option for students to not answer and this group of students was only a subset of the either sample. Still, we can not rule out some impact of students from this group providing their perceptive answers rather than their experiences.

Questionnaire ambiguity: Although we did our utmost to mitigate ambiguity in the questionnaire, it can not be completely excluded. This conclusion is supported by responses to one of the questionnaire questions where we asked the students to mention potential ambiguities in the questions. The answers highlighted that questions that aimed to compare the higher education materials with media that the students consume for leisure, were difficult to answer, or difficult to understand. Hence, we recognize that there might be some variation in these results what students included in their answer, e.g., content quality, quality of the production or the platform features.

Research focus: The study aimed to elicit how students previous experiences with online platforms affected the experiences with online teaching. The questionnaire was explicitly designed to elicit these two factors and results then synthesised to draw conclusions. From a construct validity stand-point the study is thereby perceived to be of high quality. However, there is still the risk, as discussed regarding questionnaire ambiguity, that the questionnaire questions may not have elicited the information in the right way. We do however perceive this as a limited threat since the questionnaire was iterated several times and also piloted within the sample frame with successful results.

Analysis: The main result of this work is based on formal statistical analysis. Although the sample on which the result was calculated is quite large, 431 students, in the analysis this sample was broken down in subgroups. These subgroups varied in size, with some groups being smaller, affecting their statistical power. However, once more, due to the overlapping characteristics of the student population, we perceive this threat to be minor for the study’s main conclusions. A larger threat is instead in terms of the generalizability of the result within the sub-clusters of the sample.

Generalizability: The study was performed at only one higher education institute in Sweden. Thus, it cannot be excluded that contextual, regional or national factors may affect the results. As the sample is focused on only technical engineers and nursing students, the study can not be said to be comprehensive enough to include all forms of higher education. This is a delimitation of the results, which must be considered when considering the results. In addition, this delimitation must be considered for replication of this study, where the choice of included programs may have an impact on the result.

Reliability: The questionnaire was scrutinized prior to it being sent out and was also validated in a pilot survey. However, there is still a risk that some students intentionally, or unintentionally, answered the questionnaire incorrectly, which would be a threat to the reliability of the results. Especially since the questionnaire, due to restrictions on size, did not include correlating or verifying questions. To mitigate this threat, a sanity check was done to identify extreme outliers.

4. Results

4.1. RQ1: How Do Students at BTH Experience Online Teaching in Terms of Quality and Usefulness?

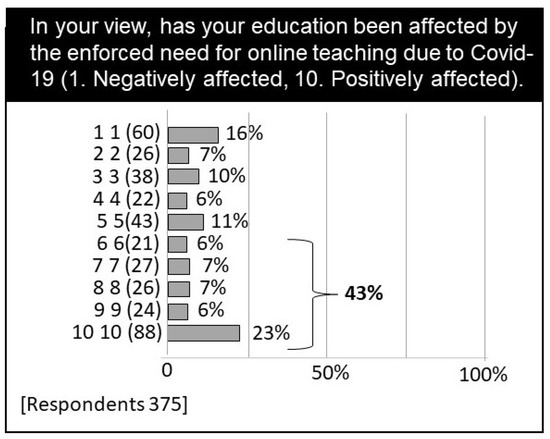

Results shows that nearly half of the students experience a positive effect from the enforced online teaching due to COVID-19, as shown in Figure 2. The question was posed as a 10 point Likert-scale question.

Figure 2.

Bar chart of student perception of COVID-19 effects on education, 43% indicate that their education has been positively affected due to the pandemic.

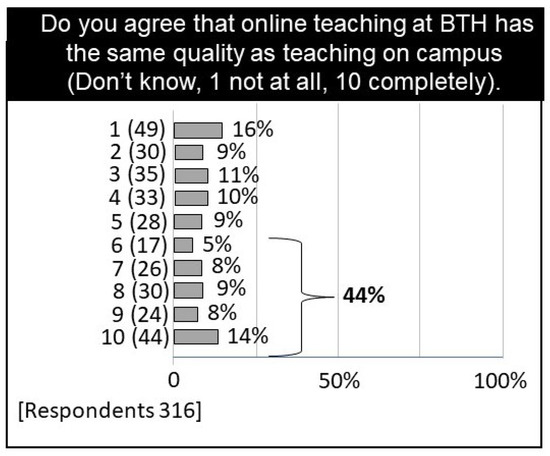

In addition, we observe that close to a majority of the students also experience that online teaching has the same quality as teaching on campus, result shown in Figure 3. The question, number 13 in the order of the survey, are posed as a 10 point Likert-scale.

Figure 3.

Bar chart visualizing student perception of online and campus teaching quality, 44% of the respondents agree that online teaching has the same quality as campus teaching.

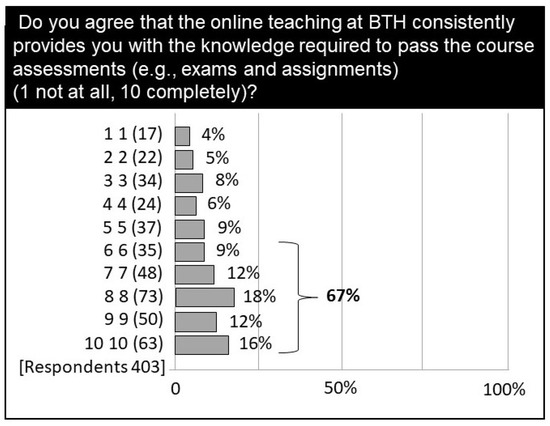

A large majority of the students agree that online teaching consistently provided them with the knowledge required to pass the course assessments (e.g., exams and assignments), result shown in Figure 4. The question use 10 point Likert scale and was number 12 in the order.

Figure 4.

Bar chart visualizing the distribution of student perception of how online teaching provides adequate knowledge to pass course assessments.

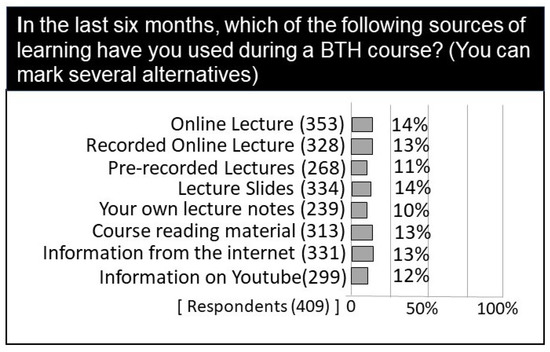

In the survey the students indicated different types of material for learning they used in a course in the last six months. A complete list of sources is listed in Figure 5. The questions was formed as a multiple choice questions and we observe that the use of learning sources are evenly distributed between different materials; online lectures, lectures notes, course reading material etc. Learning materials from Youtube or similar platforms are very often videos that the students themselves identifies as relevant and relevant to their learning process.

Figure 5.

List of sources of learning used by students, the different learning materials the students make use of are evenly distributed among the different sources.

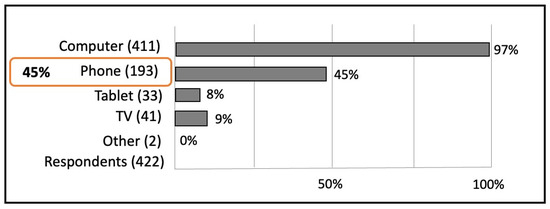

The study also shows that a clear majority of the students use computers to view online media for learning at the university. 411 students out of 422 respondents indicated that they use computers. Figure 6 also visualise that almost half of the students, 193 students, use their phone as a device for watching online media and lectures. This result could be relevant when developing online materials. Teachers should, e.g., avoid small fonts on power point presentations or too much text on one slide.

Figure 6.

List of platforms used by students to view online teaching materials. The students could mark several options. 45% of the students indicate that they use phones for online education. The computer is by far the device that students most commonly use in their education.

The qualitative analysis of 248 statements using thematic coding resulted in eight codes. Interaction/feedback was the code that contained the most comments and suggestions for improvements or observations from the students. The analysis of the comments highlights students’ need of increased feedback and interaction with teachers in online learning situations. This includes feedback on assignments and interaction in online lectures and outside actual teaching situation, e.g., through contact hours, e-mail or chat. Students want more time with teachers, as supported by two of the students “I want quick feedback from teachers. More booked times for tutoring/question sessions regarding the course” and “Some sort of mentoring/help time. Just like a zoom room every Thursday or something. Where you can just log in if you need help/wonder something.” We can conclude that whilst traditional teaching relies heavily on face-to-face interaction and communication, feedback is a central means of both communication and interaction between teachers and students within online education. Feedback is a valuable opportunity to create an active communication and relevant interaction between teacher and student, which in turn prevents the students feeling isolated. Students’ need for more interactions can be managed by online chats and discussions on LMS.

In addition, results from the quantitative analysis show that students emphasise pedagogical/didactic challenges and that they demand that teachers convey the material in more engaging ways, that the lectures are varied and that the course content is interactive course content. The latter includes aspects such as visualisations, more examples and structured material, and peer collaboration. The students point out that the courses have a high degree of lecture-based methods and are asking for more student active elements of teaching. Students want more variation and examples, as highlighted by three of the students: “That teachers do not only use the slides. It would be better if they could show via illustrations and other things too.” and “The teacher needs to be more pedagogical and make use of the digital tools available.” and “More interactive solutions during lecture. For example, live questions with some type of tool that you get to answer live.” The quantitative results contain many positive comments about recorded lectures. The students want more recorded lectures and wish that the practice of using recorded lectures will continue in a post-pandemic setting. One student expressed the following; “I think that recorded lectures should really be continued even if the distance learning is finished, this is because with recorded lectures you can always listen over and over again, you don’t have to worry about not having time to take notes when the teacher is lecturing e.g., on campus.” Technical issues were also a theme identified in the qualitative analysis, students indicated teachers’ competence with digital tools as a subject for improvement, one of the students expressed; “Basic training in Canvas & Zoom for all teachers, as well as constant access to supporting documentation on the platforms. This is to mitigate the difference in quality between courses. Furthermore, it would have been good if the university made sure that all teachers had proper cameras, microphones, and drawing boards. This would also counteract quality differences.”

Overall the qualitative analysis contained generally positive comments and suggestions of how to improve online teaching.

4.2. RQ2: Are There Differences in Experience with Online Teaching Related to Subject Areas?

Figure 7 presents the results of the hierarchical clustering as a Dendrogram. The leaves of the Dendrogram are the individual students, clustered based on the answers of all questions from the questionnaire survey. The underlying hypothesis of the analysis is that there is a correlation between the students’ previous experiences with online platforms (e.g., Facebook or YouTube) and perceptions of online learning. As visible in the figure, six distinct clusters can be identified. These clusters were then analyzed to (1) identify which program the students of a specific cluster belongs to and (2) what to what cycle students of a specific cluster belong.

Figure 7.

Result of cluster analysis, visualized in an Hierarchical Dendrogram. CX—Cluster X, ranging from cluster 1 to 6.

Analysis of (1) shows that students of a given program are randomly distributed across the clusters. In addition, these distributions vary among programs. As such, no cluster can be directly associated with any given program. Furthermore, for (2), a similar result was found, where no particular pattern could be discerned among 1st and 2nd cycle students and any particular cluster. Thus, given the questionnaire survey’s questions for both (1) and (2), we conclude that students’ previous experience with online platforms do not have a direct or major impact on the their experiences with online learning. As will be discussed in Section 5, other factors seem to be more influential.

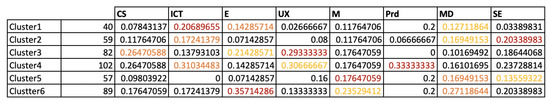

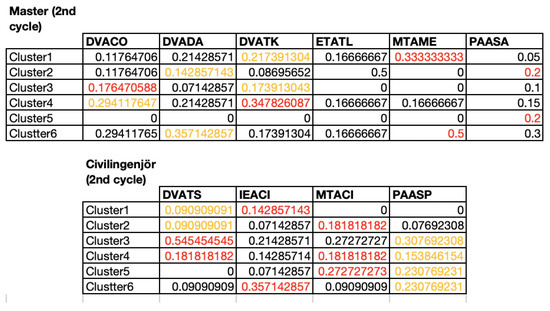

Figure 8 presents a more detailed view of the cluster where the distribution of students from the different programs are clustered and presented. The color coding shows the top three programs in each cluster as red for the most represented, orange for the second most represented and yellow for the third most represented. As can be seen, there is no discernibly pattern that shows which clusters are mostly associated with a single program. For instance, Cluster 1 has a high representation of ICT students, but also E and MD students. Looking instead across clusters we, for instance, see that ICT is also highly represented in Clusters 1, 2 and 4, with almost an equal distribution among each cluster. Similar observations can be made for most programs.

Figure 8.

Table showing the normalized distribution of students according to clusters shown in Figure 7.

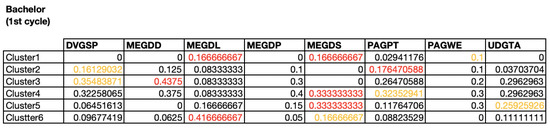

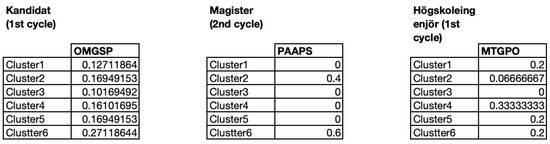

Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11 instead shows the distribution among students from 1st and 2nd cycle studies. In Figure 9 the 2nd cycle students are shown. Similarly to the distribution among programs, no discernible pattern can be seen. Similar results are shown in Figure 10 (1st cycle students) and Figure 11 (mix of first and 2nd cycle equivalent Swedish programs).

Figure 9.

Tables showing the normalized distribution of 2nd cycle (master’s level) students.

Figure 10.

Table showing the normalized distribution of 1st cycle students according to clusters shown in Figure 7.

Figure 11.

Table showing the normalized distribution of Swedish 1st and 2nd cycle students.

The pandemic and the forced embrace of online teaching raised discussions among teachers regarding how students with different subject area backgrounds would experience and utilize the online teaching and learning environment. A common assumption was that students within technical subject areas would easier adjust and benefit from online teaching compared to students within subject areas in less technical background, such as health science. In the survey, students from 20 different educational programs, from 1st cycle to 2nd cycle, participated. However, the quantitative results show no differences in how the students experience and benefit from online teaching related to different subject areas in the educational programs. In addition, no differences were identified in the data set with regards to how students from different cycles experienced online teaching. This result provides valuable insights for teachers engaged in online teaching and points towards a need to consider the mode of delivery and engagement with students in relation to the actual subject at hand rather than adjusting teaching in accordance with students’ previous experiences with online platforms.

5. Discussion

The main conclusion of this paper is that prior experience with online media platforms have no direct impact on students’ experience with online learning. No patterns could be identified with regards to what programs the students are studying nor if they were 1st or 2nd cycle students. The results stand in stark contrast to the survey of online experiences among students of Chinese undergraduate medical students [9] that was discussed in Related works. As the study investigates students’ perceptions of ongoing online education developed in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in relation to prior online learning experience they find a significant positive correlation. An important difference, however, is that the study targets a specific student group, i.e., medical students. The fact that we can find no significant correlation, then, may signify that such differences are less discernible when comparing various study programs and students groups. When studying student experiences across the curriculum, differences may be less significant, and more difficult to detect. When studying student experiences within the same student group or study program differences may be more prominent. Another potential explanation would be that lecture-based teaching is more common at BTH and that the mode of delivery is therefore not dramatically changed when transferred to online mode. Since the sample is taken from all programs at the university, however, such a conclusion cannot be made. Across the curriculum and in the different courses taught, a wide range of varying teaching methods are used at BTH. This was also the case during the pandemic.

This is not of course to say that “one size fits all” with regards to how we deliver our educational provision online, even within the same student group or study program. Learning variations will still exist, between individuals and student groups, and these must be catered to. Research finds that student-centered teaching engages students more at the same time as the level of achievement increases compared with traditional classroom settings [50]. In student-centered environments, as learning is personalized and competency-based, regardless of whether or not it is on campus or online, students take ownership over their learning [50,51,52]. In other words, a differentiated learning approach is more likely to engage and motivate more students than the traditional one-size-fits-all approach, within the same student group as well as across study program. Research also shows that student engagement not only increases student satisfaction and enhances student motivation to learn, it also reduces the sense of isolation, and improves student performance in online courses [50,51,52]. What we can say, then, based on the results of our study and previous research, is that while we should continue to push towards a student-centered teaching in our online learning platforms, we do not need to tailor-make our teaching based on the students’ previous experiences with online platforms.

Even though the results of our study indicate few or no variations in the students’ perception on online learning based on previous experience with online platforms, however, there are other factors to consider. Although this study did not explicitly investigate these factors, the qualitative answers regarding changes the students want to see with the online learning do provide some important insights. One such insight is that the students are divided when it comes to the quality of the online teaching as only 67 percent are of the opinion that the teaching has provided enough knowledge to pass assessments. Furthermore, the fact that one third of the students do not perceive the online learning to provide knowledge to pass the course assessments is an intimidating result. However, there are also several possible reasons for this outcome. It may suggest, for instance, that there is something about the way we plan and execute our teaching online that we must change. It should be emphasized, of course, that this study was performed at the end of the COVID-19 pandemic and not all teachers may have been able to transition well to online teaching. Learning activities or methods of assessments, e.g., labs or exams, may not have been fully aligned with the learning outcomes (i.e., construtively aligned [53]), specifically when swiftly transferred to an online setting. Changes in the course plans take time, and requires both careful planning and needs to follow certain university processes. Moreover, teachers may not have been trained in the differences between campus and online teaching. An alternative explanation is that the courses do not provide sufficient knowledge for students, whether on campus or online. Whilst this latter explanation cannot be discarded, we have no data to either support or decline this possibility. A third explanation could be that students may have had one or several negative experiences that influence their overall result, i.e., the result of the question does not reflect all courses, but some. Regardless of what line of argument or assumption we would like follow, the result that students do not perceive the online learning to provide enough qualitative knowledge to pass the course assessments is one of the more troubling outcomes of this study. As such, it will be investigated further at the university to find areas of improvement for the future.

Similarly to our former results, the division between students perception regarding how their education has been affected by the online learning is also troublesome. Although 43 percent of the students perceive a positive effect, 57 percent perceive it to have been negative. An interesting observation of this result is that there is a clear division between students that have negative, neutral and positive perceptions. These divisions, spread among the different programmes and types of students, once more reflect other factors that influence student perception and experience. In our previous work, we have noted that such factors include the students’ inclination towards being intrinsically or extrinsically motivated or if they are introverted or extroverted individuals [10].

One crucial conclusion that can be drawn based on the open ended questions is that the students who experience online learning lack the sense of group-belonging that comes with campus education. This factor was not explicitly elicited, but is one of the core differences between how the students work in the two educational contexts. From these results we draw the conclusion that students feel that interaction suffers from online teaching, which also relates to interaction with student colleagues. Thus, in future instances where online teaching becomes mandatory, more emphasis should be placed on creating group-belonging in the student population.

6. Conclusions

In this study, to gain insights into students’ perceptions about online learning, we have performed a questionnaire survey at Blekinge Institute of Technology. The survey included 431 students from 20 programs, ranging from technical programs to social sciences, with students of varying age and gender. The survey responses were then analyzed using descriptive statistics and qualitative analysis to draw conclusions.

Our analysis shows that regardless of the students’ previous experiences and habits regarding online platforms, e.g., video/music streaming or social media, there was no correlation with their perceptions about online teaching and learning. Moreover, there was no correlation their experiences of online learning and their program of study or whether they were 1st or 2nd cycle students. Hence, student background is not a core attribute to their perception of teaching quality and learning online.

However, the analysis of the qualitative answers from the survey do provide some additional insights. Students highlight eight factors, including interaction/feedback and pedagogical/didactic challenges with materials, as significant in their learning process. From these results we draw the conclusion that students feel that interaction suffers from online teaching, which also relates to interaction with student colleagues. An important subject for future research is thereby how to improve student group engagement and collaboration.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Å.N., A.E., E.A. and E.P.; methodology, Å.N., A.E., E.A. and E.P.; software, Å.N., A.E. and E.A.; validation, Å.N., A.E. and E.A.; formal analysis, Å.N., A.E. and E.A.; investigation, Å.N., A.E. and E.A.; resources, Å.N., A.E., E.A. and E.P.; data curation, Å.N., A.E. and E.A.; writing—original draft preparation, Å.N., A.E. and E.A.; writing—review and editing, Å.N., A.E., E.A. and E.P.; visualization, Å.N., A.E. and E.A.; supervision, Å.N., A.E. and E.A.; project administration, Å.N., A.E., E.A. and E.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and advice was sought at the Ethical Advisory Board in South East Sweden. Ethical approval was not required.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge that this work was supported by the KKS foundation by the S.E.R.T. Research Profile project (reference number 20180010) and PROMIS project (reference number 20210026) at Blekinge Institute of Technology.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interest or personal relationship that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix A. Questionnaire Guide

Appendix A.1. Research Objective

The objective of this study is to elicit, and correlate, students’ knowledge and experiences with online media platforms and correlate it with students’ experiences and perceptions with online teaching. The underlying assumption of the study is that students that have a habit of using online platforms also experience, and perceive, online teaching at least as beneficial as campus teaching.

Appendix A.2. Clarifications and Definitions

- Online platforms and media: This includes any platform that streams live or use recorded content for the purpose of learning or leisure.

- Learning compared to Leisure: Learning refers explicitly to university education and content viewed for said purpose. Leisure refers to all other contents that may be viewed for learning a craft, for enjoyment or other activity not related to university education.

Appendix A.3. Questions

Table A1.

Table with thee survey questions used in the survey.

Table A1.

Table with thee survey questions used in the survey.

| Q0 | How old are you? | 15–20, 20–25, 25–30, 30–35, 35–40, 40+ |

| Q1 | In the last six months, how many hours (estimate) have you spent per week viewing online content for learning (content explicitly for university education, e.g., lectures, provided by BTH or third parties)? | Don’t know, 0, 1–3, 4–6, 7–10, 10–20, 20–30, 30–40, 40+ |

| Q2 | In the last six months, how many hours (estimate) have you spent per week viewing online video content for leisure (content not related to University education, e.g., arts and crafts tutorials, (e)-sports, entertainment videos)? | Don’t know, 0, 1–3, 4–6, 7–10, 10–20, 20–30, 30–40, 40+ |

| Q3 | Indicate how often you use each type of following online media service (Daily, Weekly, Monthly, Never) | BTH Education (e.g., BTH play (Canvas), Zoom Lectures). Movie/Tv streaming (e.g., Netflix, ViaPlay), Social-media videos (e.g., YouTube, Vimeo, IGTV, TikTok), Live-streaming (e.g., Twitch, Facebook live, Discord), Video calls for personal use (e.g., Messenger, Skype, Zoom, Teams) |

| Q4 | At what age were you introduced to online streaming content? | Don’t know, 1–3, 4–6, 7–10, 11–13, 14–16, 17–19, 20+ |

| Q5 | What was the first online video content platform you used regularly for leisure? | Open question |

| Q6 | Which of the following are reasons why you view online video content? | Educational learning (University connected learning), Entertainment (Follow streamers/channels/influencers), Learning arts, crafts or other skills (non-university connected learning), Companionship (Social connection), Background audio (white noise), Music videos, Other |

| Q7 | Compare the following aspects of content produced by the university for learning and content that you normally view for leisure on a 10 point scale where a number closer to 1 implies university learning is better (in general) and 10 that the leisure content you view is better (in general). | Production quality (e.g., Camera, lighting, effects, etc), Content value (e.g., Interesting, informative, Educational), Entertainment value (e.g., Fun, relaxing), Connection to person presenting content (e.g., Relatable, personal, helpful), Length of content (Time), Other |

| Q8 | Which of the following devices do you use to view online video content for learning? | Computer, Phone, Tablet, TV, Watch, Other |

| Q9 | Which of the following devices do you use to view online video content for leisure? | Computer, Phone, Tablet, TV, Watch, Other |

| Q10 | In the last six mohths, which of the following sources of learning did you use during a course? | Online Lecture, Recorded Online lecture, Pre-recorded Lectures, Lecture slides, Lecture notes, Course reading materials (e.g., course book or articles), Information on the internet (e.g., through Google or Google scholar), Information on Youtube or similar platform |

| Q11 | Do you agree that the online teaching content in courses at BTH provides you with the information you need to meet the course objectives (1 not at all, 10 completely) | Likert scale |

| Q12 | Do you agree that the online course content at BTH provides you with the knowledge required to pass the course assessments (1 not at all, 10 completely)? | Likert scale |

| Q13 | Do you agree that online teaching at BTH has the same quality as classroom teaching (Don’t know, 1 not at all, 10 completely). | Likert scale |

| Q14 | Do you agree that the teachers at BTH are good at online teaching/education (1 not at all, 10 completely). | Likert scale |

| Q15 | Do you agree that you would acquire the knowledge of the lectures better if they were subtitled? (1 completely disagree, 10 completely agree). | Likert scale |

| Q16 | Do you experience that your education has been affected by the enforced need for online education due to COVID-19 (1. Negatively affected, 10. Positively affected). | Likert scale |

| Q17 | What, if any, changes would you like to see in existing online teaching (e.g., Add subtitles, more teacher engagement, more flexibility)? | Likert scale |

| Q18 | Was any of the questions in the questionnaire ambiguous or difficult to answer or do you have any other comments about digital learning for BTH administration? | Open question |

References

- McCullogh, N.; Allen, G.; Boocock, E.; Peart, D.J.; Hayman, R. Online learning in higher education in the UK: Exploring the experiences of sports students and staff. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2022, 31, 100398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, G.; Grenha Teixeira, J.; Torres, A.; Morais, C. An exploratory study on the emergency remote education experience of higher education students and teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2021, 52, 1357–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguliera, E.; Nightengale-Lee, B. Emergency remote teaching across urban and rural contexts: Perspectives on educational equity. Inf. Learn. Sci. 2020, 121, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, S.I.; Nistor, N.; Scheibenzuber, C. Online teaching and learning in higher education: Lessons learned in crisis situations. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 121, 106789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rapanta, C.; Botturi, L.; Goodyear, P.; Guàrdia, L.; Koole, M. Balancing technology, pedagogy and the new normal: Post-pandemic challenges for higher education. Postdigital Sci. Educ. 2021, 3, 715–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziuban, C.; Graham, C.R.; Moskal, P.D.; Norberg, A.; Sicilia, N. Blended learning: The new normal and emerging technologies. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2018, 15, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapanta, C.; Botturi, L.; Goodyear, P.; Guàrdia, L.; Koole, M. Online university teaching during and after the COVID-19 crisis: Refocusing teacher presence and learning activity. Postdigital Sci. Educ. 2020, 2, 923–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevanović, A.; Božić, R.; Radović, S. Higher education students’ experiences and opinion about distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2021, 37, 1682–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Xie, A.; Wang, W.; Wu, H. Association between medical students’ prior experiences and perceptions of formal online education developed in response to COVID-19: A cross-sectional study in China. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e041886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, A.; Alégroth, E.; Nygren, Å. Online Media Platforms’ influence on student perception of Blended Learning. J. Teach. Learn. High. Educ. Malmö Univ. 2020, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newswire, P. Blackboard Campus (TM) Makes the Online Campus a Reality for Teaching and Learning-Anytime, Anywhere. 1999. Available online: https://www.blackboard.com/ (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Hrastinski, S. What do we mean by blended learning? TechTrends 2019, 63, 564–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurley, L.E. Educators’ Preparation to Teach, Perceived Teaching Presence, and Perceived Teaching Presence Behaviors in Blended and Online Learning Environments. Online Learn. 2018, 22, 197–220. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, D.H.; Morris, M.L.; Kupritz, V.W. Online vs. blended learning: Differences in instructional outcomes and learner satisfaction. J. Asynchronous Learn. Netw. 2007, 11, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, J.; Verleger, M.A. The flipped classroom: A survey of the research. In Proceedings of the 2013 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition, Atlanta, Georgia, 23–26 June 2013; pp. 23–1200. [Google Scholar]

- Maertens, H.; Madani, A.; Landry, T.; Vermassen, F.; Van Herzeele, I.; Aggarwal, R. Systematic review of e-learning for surgical training. J. Br. Surg. 2016, 103, 1428–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kentnor, H.E. Distance education and the evolution of online learning in the United States. Curric. Teach. Dialogue 2015, 17, 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Sweetman, D.S. Making virtual learning engaging and interactive. FASEB BioAdvances 2021, 3, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.L.; Dickson-Deane, C.; Galyen, K. e-Learning, online learning, and distance learning environments: Are they the same? Internet High. Educ. 2011, 14, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curelaru, M.; Curelaru, V.; Cristea, M. Students’ perceptions of online learning during COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative approach. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magomedov, I.; Khaliev, M.S.; Khubolov, S. The negative and positive impact of the pandemic on education. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1691, 012134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sormunen, M.; Saaranen, T.; Heikkilä, A.; Sjögren, T.; Koskinen, C.; Mikkonen, K.; Kääriäinen, M.; Koivula, M.; Salminen, L. Digital learning interventions in higher education: A scoping review. CIN Comput. Inform. Nurs. 2020, 38, 613–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duszenko, M.; Fröhlich, N.; Kaupp, A.; Garaschuk, O. All-digital training course in neurophysiology: Lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Med. Educ. 2022, 22, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motte-Signoret, E.; Labbé, A.; Benoist, G.; Linglart, A.; Gajdos, V.; Lapillonne, A. Perception of medical education by learners and teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional survey of online teaching. Med. Educ. Online 2021, 26, 1919042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selco, J.I.; Habbak, M. Stem students’ perceptions on emergency online learning during the covid-19 pandemic: Challenges and successes. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpert, W.T.; Couch, K.A.; Harmon, O.R. A randomized assessment of online learning. Am. Econ. Rev. 2016, 106, 378–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, C.M.; Friedmann, E.; Hill, M. Online course-taking and student outcomes in California community colleges. Educ. Financ. Policy 2018, 13, 42–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettinger, E.P.; Fox, L.; Loeb, S.; Taylor, E.S. Virtual classrooms: How online college courses affect student success. Am. Econ. Rev. 2017, 107, 2855–2875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kofoed, M.; Gebhart, L.; Gilmore, D.; Moschitto, R. Zooming to Class?: Experimental Evidence on College Students&Apos; Online Learning During COVID-19. Online Learning During COVID-19. IZA Discussion Paper. 2021. Available online: https://www.iza.org/publications/dp/14356/zooming-to-class-experimental-evidence-on-college-students-online-learning-during-covid-19 (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Kauffman, H. A review of predictive factors of student success in and satisfaction with online learning. Res. Learn. Technol. 2015, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michinov, N.; Brunot, S.; Le Bohec, O.; Juhel, J.; Delaval, M. Procrastination, participation, and performance in online learning environments. Comput. Educ. 2011, 56, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coman, C.; Țîru, L.G.; Meseșan-Schmitz, L.; Stanciu, C.; Bularca, M.C. Online teaching and learning in higher education during the coronavirus pandemic: Students’ perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khobragade, S.Y.; Soe, H.H.K.; Khobragade, Y.S.; bin Abas, A.L. Virtual learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: What are the barriers and how to overcome them? J. Educ. Health Promot. 2021, 10, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, C.B.; Moore, S.; Lockee, B.B.; Trust, T.; Bond, M.A. The Difference between Emergency Remote Teaching and Online Learning. 2020. Available online: https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-difference-between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-online-learning (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Krashen, S.D. Explorations in Language Acquisition and Use. 2003. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwi70uPUj4X9AhXixgIHHcBmCAsQFnoECBwQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.researchgate.net%2Fprofile%2FStephen-Krashen%2Fpublication%2F349255011_Explorations_in_Language_Acquisition_and_Use%2Flinks%2F6026d94fa6fdcc37a8219127%2FExplorations-in-Language-Acquisition-and-Use.pdf&usg=AOvVaw3CZzy5oz3zZH_Y9olS9tQK (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Quinn, B.; Field, J.; Gorter, R.; Akota, I.; Manzanares, M.c.; Paganelli, C.; Davies, J.; Dixon, J.; Gabor, G.; Amaral Mendes, R.; et al. COVID-19: The immediate response of european academic dental institutions and future implications for dental education. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2020, 24, 811–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, L.R.; Tanti, I.; Maharani, D.A.; Wimardhani, Y.S.; Julia, V.; Sulijaya, B.; Puspitawati, R. Student perspective of classroom and distance learning during COVID-19 pandemic in the undergraduate dental study program Universitas Indonesia. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darras, K.E.; Spouge, R.J.; de Bruin, A.B.; Sedlic, A.; Hague, C.; Forster, B.B. Undergraduate radiology education during the COVID-19 pandemic: A review of teaching and learning strategies. Can. Assoc. Radiol. J. 2021, 72, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dost, S.; Hossain, A.; Shehab, M.; Abdelwahed, A.; Al-Nusair, L. Perceptions of medical students towards online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic: A national cross-sectional survey of 2721 UK medical students. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e042378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavru, S. A critical examination of recent industrial surveys on agile method usage. J. Syst. Softw. 2014, 94, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, F.J., Jr. Survey Research Methods; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ash, M.G. Bachelor of What, Master of Whom? The Humboldt Myth and Historical Transformations of Higher Education in German-Speaking Europe and the US 1. Eur. J. Educ. 2006, 41, 245–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, S.R.; Whitcomb, M.E.; Weitzer, W.H. Multiple surveys of students and survey fatigue. New Dir. Inst. Res. 2004, 2004, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, W.R.; He, J. External validity in IS survey research. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2005, 16, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boberg, A.L.; Morris-Khoo, S.A. The Delphi method: A review of methodology and an application in the evaluation of a higher education program. Can. J. Program Eval. 1992, 7, 27–39. [Google Scholar]

- Nemoto, T.; Beglar, D. Likert-scale questionnaires. In Proceedings of the JALT 2013 Conference Proceedings; JALT: Tokyo, Japan, 2014; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Baruch, Y.; Holtom, B.C. Survey response rate levels and trends in organizational research. Hum. Relations 2008, 61, 1139–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, F. Hierarchical clustering. In Introduction to HPC with MPI for Data Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 195–211. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L.; Strutzel, E. The discovery of grounded theory; strategies for qualitative research. Nurs. Res. 1968, 17, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrington, J.; Oliver, R.; Reeves, T.C. Patterns of engagement in authentic online learning environments. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 2003, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayens, W.; Ellis, A. Creating a student-centered learning environment online. J. Stat. Educ. 2018, 26, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonassen, D.H. Revisiting activity theory as a framework for designing student-centered learning environments. Theor. Found. Learn. Environ. 2000, 89, 121. [Google Scholar]

- Biggs, J. Enhancing teaching through constructive alignment. High. Educ. 1996, 32, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).