Abstract

Blended learning is receiving more and more attention due to social changes, technological advances, and the increasing internationality of studies, and research needs to be carried out to explore the possibilities this instruction modality offers to university students. This project aimed to test the feasibility and success of a blended course on research and EFL skills and to determine whether there is an internationally shared criterion when assessing students’ scientific work. To do so, a short module on research skills was designed and implemented with 30 students from the BSc in Optics and Optometry from the Complutense University of Madrid, whose final project, the production of a scientific poster, was assessed by three instructors from different universities. The results show that the content and modality of the teaching were successful in the increase in students’ research and language skills. The assessment of the posters showed heterogeneous evaluations regarding the quality of their visual features and their contents. Therefore, more research is needed on international perspectives about the presentation of results in the academic and scientific genre to pursue the creation and dissemination of homogeneous criteria, and therefore improve students’ performance with an international value.

1. Introduction

Over the past years, blended learning has emerged as a popular alternative to progress effectively in the transition from a traditional learning model to a model that integrates electronic environments and resources [1]. The meaning of the term “blended learning” has, however, been used ambiguously. As Ref. [2] points out, there are two definitions which are the most common definitions that can be found in the literature. On the one hand, Ref. [3] (p. 5) indicates that blended learning is based on the combination of “face-to-face instruction with computer-mediated instruction”. On the other hand, Ref. [4] (p. 96) is more specific and indicates that blended learning combines “face-to-face learning experiences with online learning experiences”. Therefore, it can be concluded that for learning and teaching to be commonly considered blended, it must include face-to-face and online instruction. However, there are different ways to implement and combine face-to-face and online instruction. For example, teaching and learning may occur in real time either having students both online and on-site during the same session—with online students attending from a classroom in a different campus or connected individually through a videoconference with their own devices—or having fully on-site sessions alternated with completely remote sessions [5,6,7].

Additionally, some other parameters have also been considered in the definitions of blended learning, apart from students’ location and the use of technology. For example, the use of different groupings (individual vs. group work) and mode (synchronous vs. asynchronous work and activities) may also play a role in blended learning [8]. Therefore, blended learning may actually involve the combination of options regarding space (students and instructor’s location, this being either on-site or online), time (synchronous meetings and activities or asynchronous work and materials), and the degree of cooperation among students (individual and group work).

Previous work on blended learning usually combines some but not all of the options for those parameters. For example, studies may deal with online asynchronous instruction but not online synchronous instruction [9,10,11,12], they may analyse online instruction but not on-site instruction [13,14,15], or they may focus on individual on-site and online work but not on group on-site and online work [16,17]. Therefore, studies testing the implementation of courses combining all options are still scarce.

Blended learning has received special attention in the higher education context [18,19]. Due to its specific features, presented above, it is a very suitable methodology for courses that aim to have national and international students. By attending online, students can easily take courses that are taught at international universities without leaving their local institutions. This way, students can integrate a course from an international university as part of their ordinary instruction. As a result, degrees can be designed with a more international view, combining courses from different universities.

However, some issues may arise that deter students from doing so. For example, students may have pedagogical adjustment difficulties due to teaching methods and styles, or they may think that expectations from international universities may be different from those they are accustomed to Refs. [20,21,22,23]. They may also avoid participating in class due to a lack of confidence in their competency in the foreign language used [24,25]. There may also be curricular concerns related to a cultural bias in curricula [26] and assessment procedures may not be equally adequate for some international students’ learning styles [23].

Conducting research and research skills cannot be separated from university instruction. These skills are not only necessary for academic life, but they are also important for students’ professional life after their university period [27,28,29]. Research skills have already been seen as a cross-disciplinary subject and introduced into the curriculum [30]. However, in order to promote students’ internationalisation and their success beyond their home university, it is important to provide students with common, internationally validated knowledge on how to conduct research and communicate their research results, but progress on this issue still needs to be made.

Thus, research skills and foreign language (English) skills are ideal content to implement blended learning since they are key skills for university students to develop. The teaching of these skills makes it possible to virtually target any student at any university and, consequently, a blended course on how to conduct research and communicate research results in English may thus exploit the possibilities that blended instruction offers, as well as make it accessible to international students.

More specifically, such a blended course could include a theoretical part and a more practical part where students put the new concepts into practice while working in a foreign language. This can be carried out by asking students to conduct research and present their results in a scientific poster, since the design and creation of this type of poster has already been shown to have several benefits for students, including the improvement of effective communication [31], content understanding [32], and literacy and writing skills [33].

1.1. Objectives

For the reasons presented above, the aim of the exploratory study presented in this paper was to test the feasibility and success of a blended course on research and EFL skills that might be implemented with students from different universities at the same time and receive an internationally valid assessment. To do so, some more specific aims were designed: firstly, to design and create a short module addressing the specific skills to be developed; secondly, to test the implementation of such a module, including synchronous and asynchronous, group and individual, and online and on-site work; thirdly, to test whether taking the module may have a positive influence on students’ perspectives on internationalisation and their confidence on their research and foreign language skills; and fourthly, to determine whether there are internationally shared criteria when assessing students’ scientific work. Thus, the study addresses blended learning from a comprehensive point of view, and it contributes to the teaching of research skills and the international understanding of these skills.

1.2. Research Questions

The present study tries to answer the following research questions regarding the design and implementation stages of the short module:

- Can a discussion group with instructors from international universities be used to design a module avoiding in-house perspectives? If so, what issues may arise in the design of the module and the implementation of the group?

- Can blended learning courses combine synchronous and asynchronous, group and individual, and online and on-site work? If so, what issues may arise in their implementation?

With respect to the outcomes and success of the module concerning its contents, two questions are posed:

- What perspectives do students have about internationalisation? Can this view be changed by taking a short module with internationalisation aims?

- Are research and foreign language skills important to students at university? If so, can these skills be improved by taking a short module?

Finally, shared instructors’ views on students’ performance are also a key issue in the success of a module that comprises national and international students. In relation to this, one research question is asked:

- Do instructors share common criteria internationally when assessing students’ work in a common field of higher education, such as conducting research and presenting their results?

Answering these questions through this exploratory study will highlight some specific current needs that instruction may deal with when trying to be opened to international students. Additionally, the description of the design and implementation of the module can be used as an orientation for future similar educational content and practices.

2. Materials and Methods

This section presents the participants, materials, and procedure followed to carry out the study. It must be noted that the participation in this project was limited, both in the number of students and instructors, due to its exploratory nature.

2.1. Participants

The participants included students and instructors. With respect to the former, 30 students from the Complutense University of Madrid participated in the study. They were all students from the BSc in Optics and Optometry who were taking the optional course in English applied to Optics and Optometry and, although most of them were 19 years old, and thus in their 2nd year, there were also some students in their 3rd and 4th years. Their English level was around B2, as checked in an entry test taken on the first day of the course.

Regarding instructors, a total of five took part in the study, all of them having research experience and fluent in English. These five instructors include the two authors of this paper, together with an instructor from Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne University, the University of Rennes 1, and the University of Trento.

2.2. Resources

Since instruction and collaboration were done either on-site or online, the key resources and materials used in the study include a classroom, online communication tools, questionnaires, and a Learning Management System (LMS).

The classroom was equipped with the following items: a digital board connected to a computer, whose screen could be shared through a videoconference session; a microphone, so that students attending online could hear the instructor; speakers, to hear online students’ oral contributions; a camera, for online students to see the room, their classmates, and the board; and chairs and hexagonal tables, which were better suited for collaborative work. Since students attending on-site needed an electronic device (either their smartphones, a laptop, or a tablet) to work with students attending online, they were asked to bring their own devices. However, the classroom was also equipped with some tablets at the groups’ disposal in case any members of the group had not brought one. Additionally, on-site students were recommended to bring their own headphones with microphones to be able to communicate with their online group members more conveniently.

Online communication tools (Google Meet, Google Drive) were used to enable collaboration among instructors from the different universities involved. Microsoft Teams was used for online sessions with students.

Some questionnaires were designed with Google Forms and used to collect data. First, feedback about the initial design of materials for the short module was obtained through the questionnaire in Appendix A. Posteriorly, students filled in a total of four questionnaires. These questionnaires included a pre-test and a post-test on internationalisation views (Appendix B and Appendix C, respectively), and a pre-test and a post-test on research and language skills (Appendix D and Appendix E). The pre-tests were taken at the beginning of the first session and the post-tests were taken at the end of the second session. Finally, instructors assessed students’ work with a rubric designed in the form of a questionnaire addressing several aspects of the scientific posters (Appendix F), including layout, visual appearance, graphics, content, and English (the foreign language used). Instructors filled in this questionnaire in July 2022.

2.3. Procedure

The experimentation was divided into two phases. The first phase consisted of the planning, design, and creation of a short module in English targeted at university students on what research is and how to present research results through a scientific poster. It had the specific purpose of dealing with any issues involved in the design of a blended activity that involves instructors and students from different universities.

The second phase consisted of the implementation of the educational content created in the first phase and involved the teaching of the contents, the design of a scientific poster in English by students and the assessment of students’ work by instructors from different universities. It had the specific purpose of testing the materials previously created and comparing international criteria regarding students’ work.

In the first phase, the authors of this paper planned and prepared the contents and materials for the short module to be posteriorly implemented. A discussion group was formed together with the instructor from Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne University; the materials were agreed on, revised, and corrected to promote and guarantee an international view on the topics dealt with and avoid in-house preferences.

In the second phase, the authors implemented the sessions with the students. Students attended a total of two two-hour synchronous sessions, one in each of the last two weeks of April 2022. Before that, they were asked to check the materials prepared in the first phase about conducting research and writing scientific posters, which added up to a total of about an half an hour long. This task was done asynchronously and individually, and the materials had been uploaded to the virtual course created specifically for this experiment, inside the university’s learning management system (Moodle).

Half the students were asked to attend the synchronous sessions online (an online session was created in Microsoft Teams), while the other half attended on-site (but they also joined the online session to be able to interact with online students). During these sessions, students were divided into groups of 5 (a total of 6 groups) which combined on-site and online students. Each of the groups chose one of the given topics for research, which were not subject-specific, but dealt with general issues such as social media, fake news, and educational resources. Apart from working on their posters, students also produced an oral explanation for them, but this was not assessed as part of the study, since the focus here was on the written poster itself. While students were allowed to continue their research outside the class between the two sessions in case they wanted to use specific materials, instruments, or facilities, they were not allowed to continue working on their posters. Their research was expected to be simple, since the focus was on following a scientific procedure and communicating their findings, and not on obtaining revealing results.

For the assessment process regarding students’ work, three instructors were involved: one of the authors of this paper together with the instructors from the University of Rennes 1 and the University of Trento.

3. Results

This section presents the results obtained from the study. They are divided into categories matching the specific aspects analysed. Due to the exploratory nature of the project, as mentioned above, the results shown in this section and discussed in the following one must always be considered within their limits, and generalisations beyond the participants’ profiles cannot be made at this point. More extensive participation would be needed to establish general patterns across Europe. However, the results may well be seen as indicators of the need for further research following this same line.

3.1. Material Design and Creation

The first phase of the study involved the design and creation of the materials that would be posteriorly used as the theoretical base for the short module on conducting research and designing scientific posters. They were created with the purpose of being equally useful and valid for national (Spanish) and international European students, so, apart from being created in English, it was necessary to avoid an in-house perspective on the topic. For this reason, a discussion group was created with the collaboration of an instructor from a university based in a different European country from the authors. This external instructor participated in the general discussion of the feasibility of implementing such a module internationally as well as in the revision of the materials and provided some feedback during an online discussion session and through a questionnaire (Appendix A). Below are presented the final components of the module and the answers to the questionnaire.

The short module comprised two units which were recorded in videos consisting of a PowerPoint presentation with oral explanations. The first unit was titled “Scientific research” and explained the following topics: concepts, types, and elements. These contents were divided into three videos. The second unit was titled “The scientific poster” and covered the differences between posters and papers, the characteristics and contents of posters, and some examples. It was divided into four videos. A more detailed distribution of the contents and the length of the videos can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1.

Distribution of contents and length for the short module videos.

It was also agreed that two synchronous two-hour sessions would be devoted to students’ work. Prior to the first of them, students would need to have watched the videos asynchronously. The videos were uploaded to the university LMS in a course created specifically for this module, which would also be used by students to upload their work. In the first session, students would create groups and start working on their research. In the second session, students would continue and finish their work. The number of groups and members might vary depending on the number of students participating in the activity.

With respect to the feedback obtained, the results were highly positive. Regarding the first part of the questionnaire, involving the collaboration process, collaboration was seen as very good (Question 1) and communication means were considered adequate (Question 2). In the benefits that had been obtained out of the collaboration (Question 3), the sharing of working methods was mentioned as a difficulty in the collaboration (Question 4), and the time distribution for the tasks was pointed out, since they were close to the Christmas break in December 2021. Consequently, organisation and collaboration dates were regarded as an aspect for future improvement (Question 5). Regarding the second part of the questionnaire, about the module design, the topic was considered to be highly relevant, since university students need to communicate their research results in a synthetic way to a diverse public (Question 6). The materials were seen as informative enough for the task, taking into account international students’ different research backgrounds (Question 7). The videos recorded were positively perceived (Question 8). Finally, the participant indicated as a general suggestion for further improvement the creation of a list of the skills that students are expected to develop and explaining them (Question 9).

Finally, during the discussion session, important issues arouse, including students’ knowledge about LMSs and schedule (in)compatibilities among universities.

3.2. Internationalisation in the University Environment

Since, among other topics, this paper deals with having an international perspective on conducting research, students were asked about their views on internationalisation in the university environment. The topic was also mentioned in the first of the two synchronous sessions, since the purpose of the module was to improve their research and language skills to conduct research internationally. The following statements summarise the results obtained in the pre- and post-tests (Appendix B and Appendix C) completed by the 30 students who participated in the study.

- 70% of the students had not studied abroad but they would like to (90% out of the 70%)—or they had and would like to again (78% out of the 30%);

- 90% of the students would prefer to go physically to a foreign university rather than take their courses online from their home university (10%);

- 73% of the students had not cooperated with international students for academic purposes, but they would like to (90% out of the 73%);

- 63% of the students thought that academic expectations of universities regarding students differ internationally;

- 92% of the students thought that working with international students for their assignments would increase their interest in internationalisation;

- 92% of the students thought that if they had an international classmate attending their classes online, they would be more likely to do the same.

3.3. Research and Language Skills

Another issue involved in this study was students’ research skills and their EFL skills. The contents and materials of the module were designed address the former, while they were created in English and students’ work had to be completed in that same language to address the latter. Students’ views were collected through two questionnaires, a pre- and a post-test (Appendix D and Appendix E). The following results summarise students’ answers:

- 91% of the students had not studied at a foreign university;

- 91% of the students thought that conducting research is important in their degree;

- 100% of the students thought that conducting research is important for national and international students;

- 82% of the students had been asked to conduct research at some point in their degree;

- 70% of the students had not had any specific training on how to conduct research in their degree;

- 52% of the students did not think that they were prepared to carry out research, but 87% of the students thought they were prepared after the module was over;

- 87% of the students thought their knowledge about research and scientific communication has improved after the sessions;

- 87% of the students thought that working with research material and producing a poster and an oral explanation in a foreign language has helped them improve their linguistic skills.

3.4. Students’ Posters Assessment

As mentioned above, this part of the study was possible thanks to the contribution made by three instructors from the Complutense University of Madrid, the University of Trento, and the University of Rennes 1. All these instructors hold a PhD, although in different fields (health, linguistics, computer science education), were fluent in English, and had shared their research via different academic means. They assessed the posters created by the six groups of students according to five parameters: layout, visual appearance, graphics, content, and English. For each of these, instructors had to choose among four levels of performance and could provide additional comments. Additionally, at the end of the assessment, it was possible to provide final comments on any aspects of the posters.

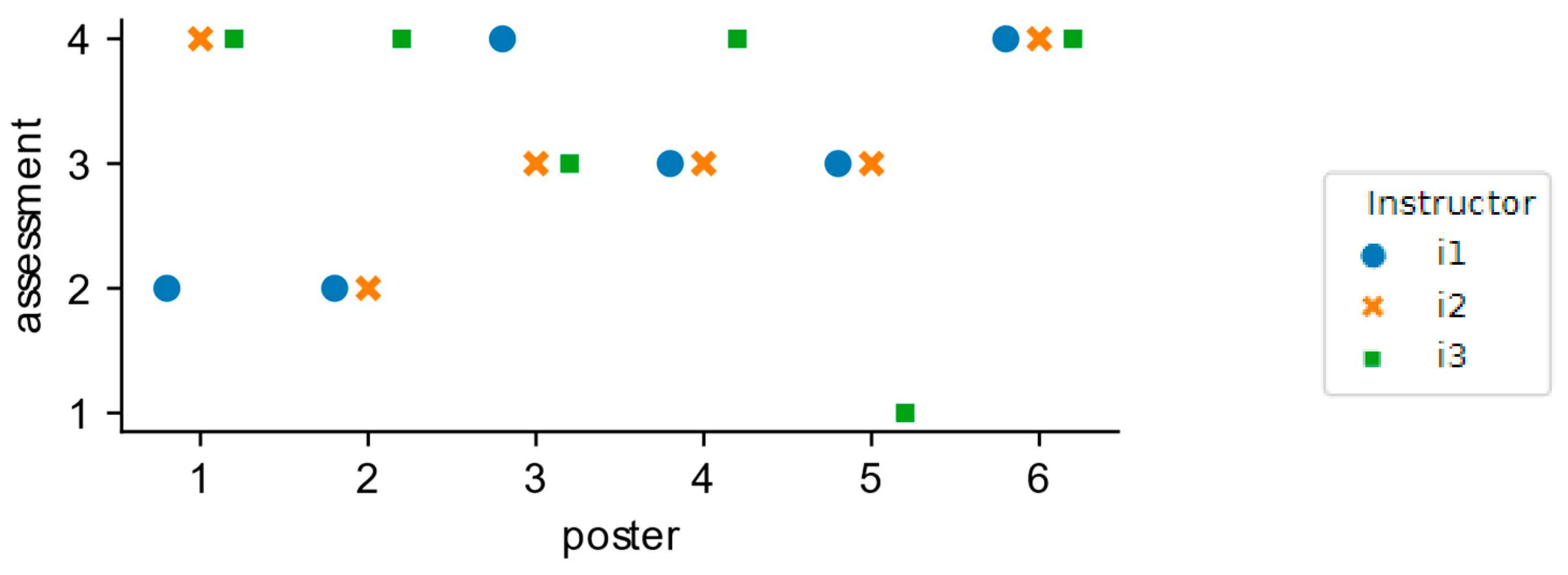

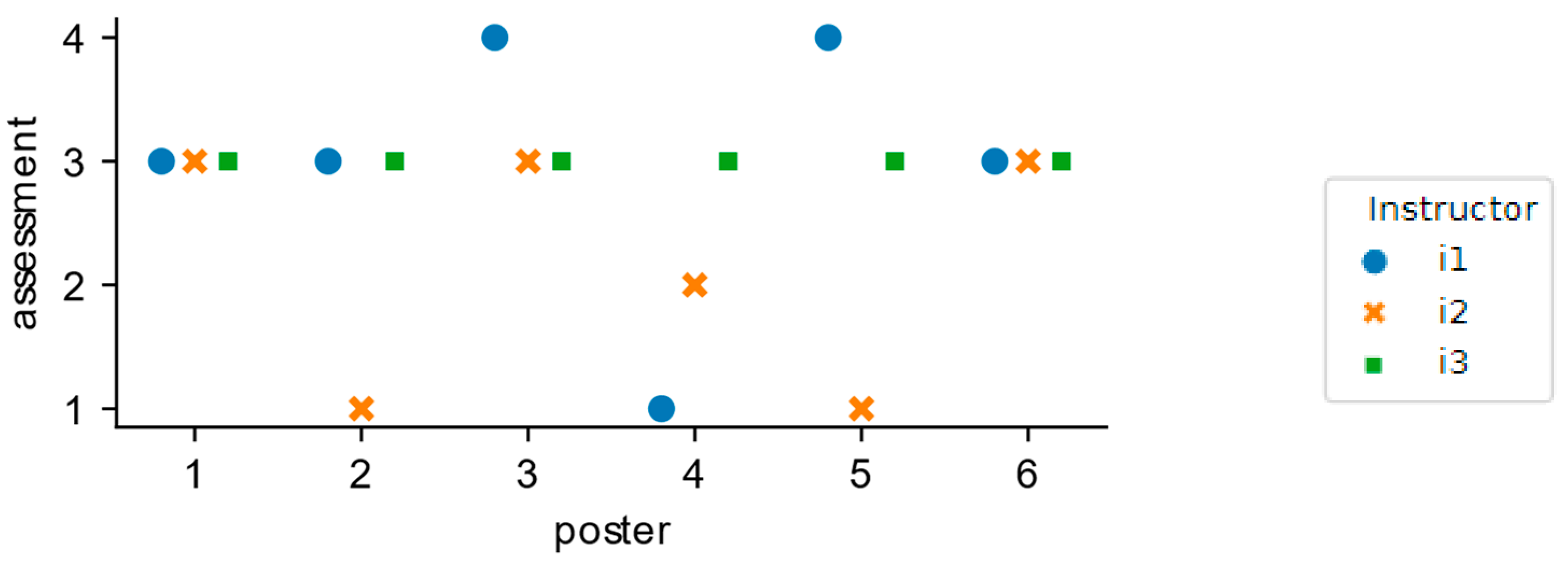

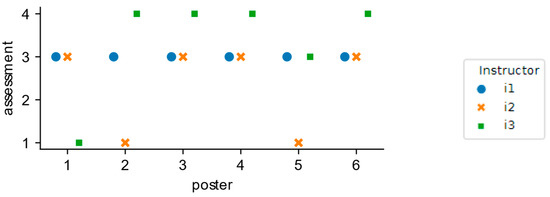

With respect to the first aspect, layout, the options for the assessment were the following, from 1 (worst) to 4 (best): “1. Poster structure is difficult to follow”, “2. The poster shows some organisation”, “3. The poster is organised and the flow of information is appropriate”, and “4. The poster is organised, the flow of information is appropriate, and prominent space is given to most important information”. The answers can be found in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Layout assessment.

The answers show some disagreement in the quality of the layout in posters 1 to 5. In posters 1 and 5, the disagreeing mark falls on a lower option, while the opposite happens in posters 2, 3, and 4, where the disagreeing assessment has a more positive evaluation than the other two. There is complete agreement, however, in poster 6, with the highest possible rating.

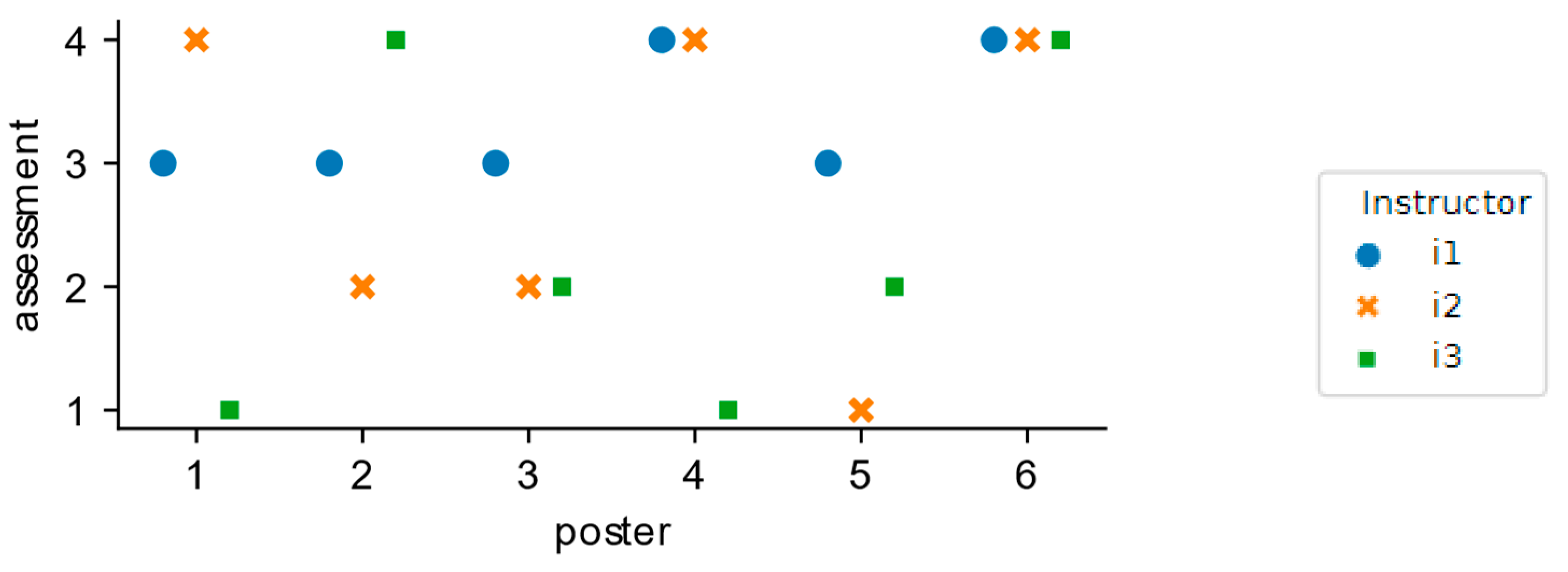

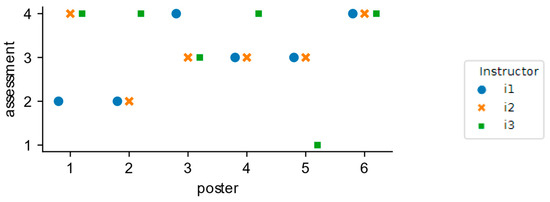

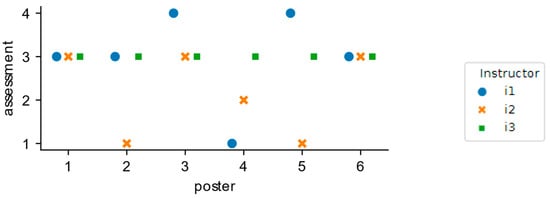

Regarding visual appearance, the options were “1. Font style, font size, spacing, colours and design style are not adequate”, “2. 1–2 items among font style, font size, spacing, colours and design style are adequate”, “3. 3–4 items among font style, font size, spacing, colours and design style are adequate”, and “4. Font style, font size, spacing colours and design style are adequate.” The assessment is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Visual appearance assessment.

Instructors show a higher degree of disagreement in their assessment of this item. In this case, posters 1, 2 and 5 have three different ratings, while two instructors agreed in their assessment of posters 3 and 4. As for the previous item, all instructors agree in giving poster 6 the highest possible rating.

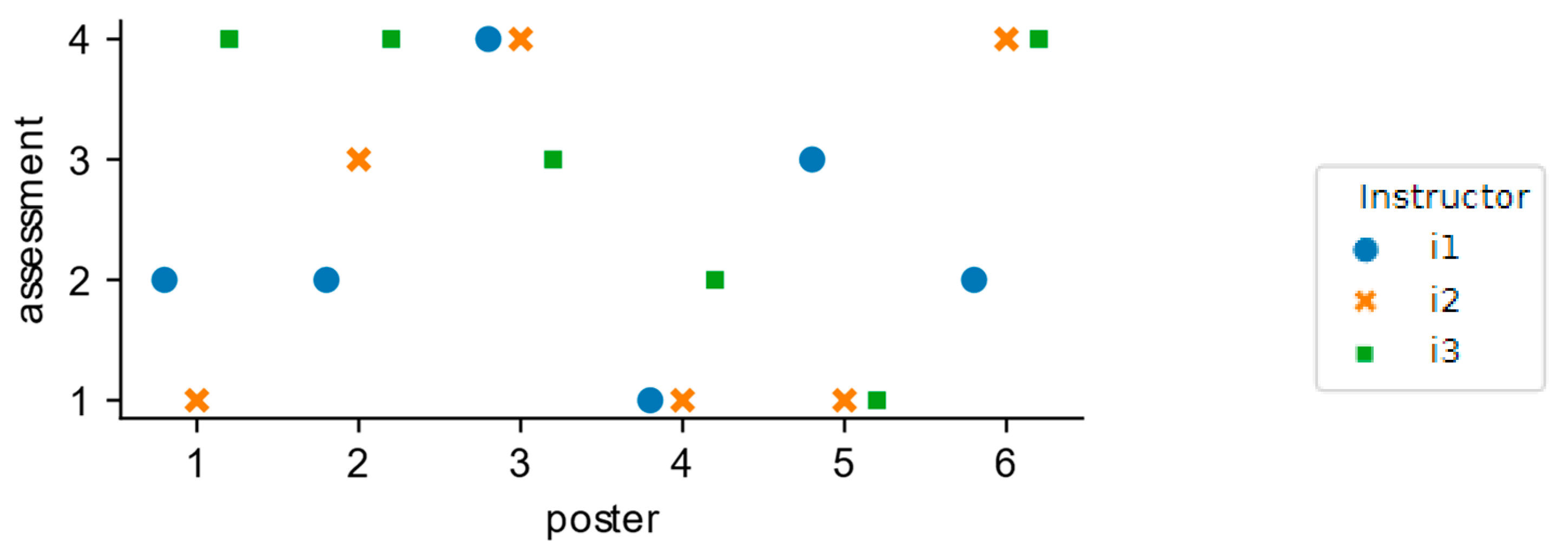

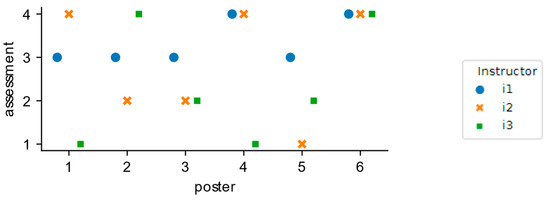

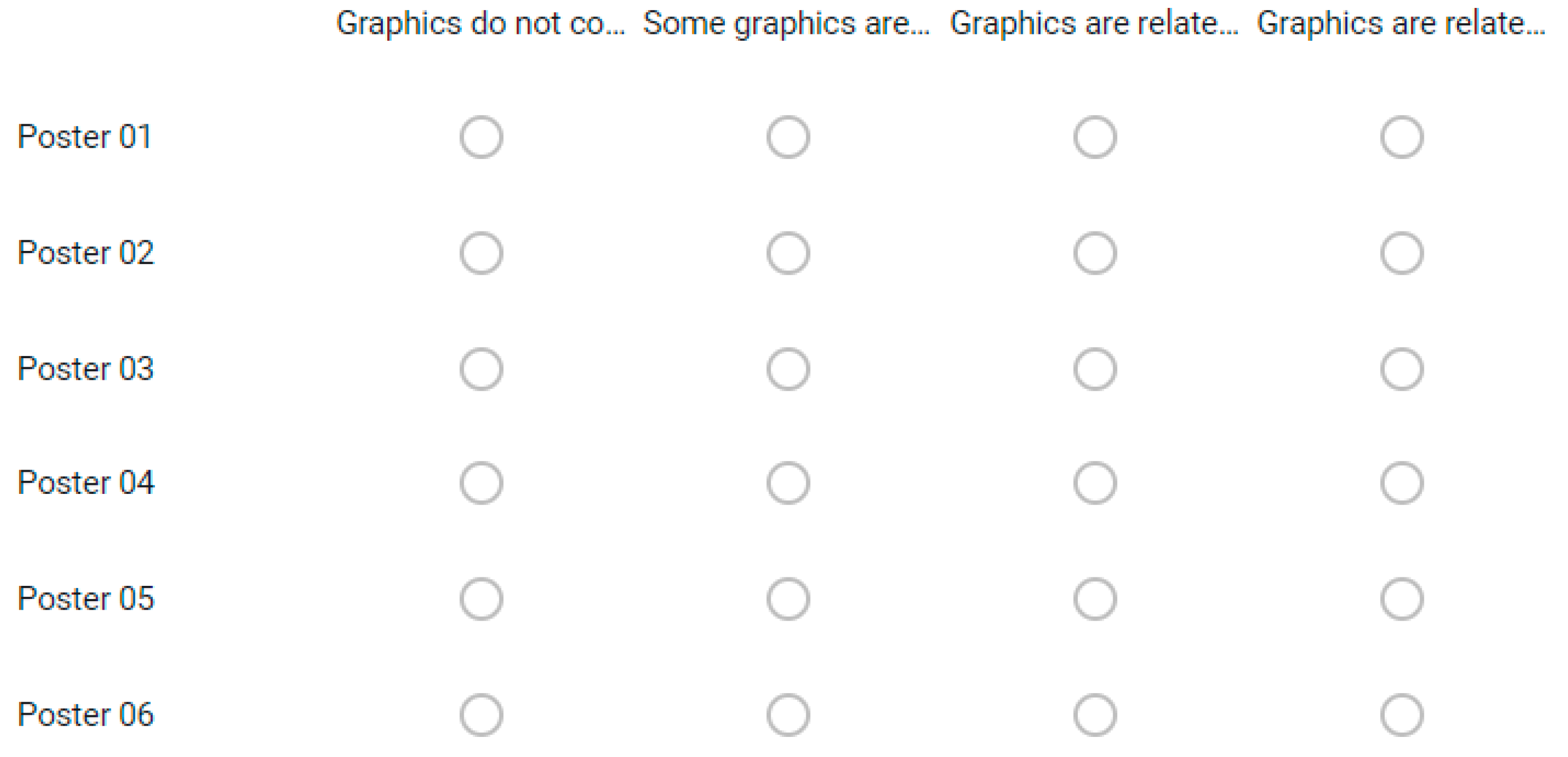

With respect to graphics, instructors could choose from “1. Graphics do not contribute to understanding the poster”, “2. Some graphics are related to the topic and make it easier to understand”, “3. Graphics are related to the topic and make it easier to understand” and “4. Graphics are related to the topic, make it easier to understand and are presented in adequate places and sizes.” The results are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Graphics assessment.

Similarly to the previous item, three different ratings can be found in some posters (1 and 2), while partial agreement is observed in others (posters 3, 4, 5 and 6). Sometimes, instructors agree on a higher mark (posters 3 and 6), but in the other cases (posters 4 and 5) they agree on a lower one. Unlike in the two previous assessed items, here there is no total agreement for any of the posters.

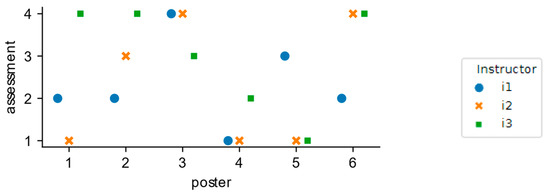

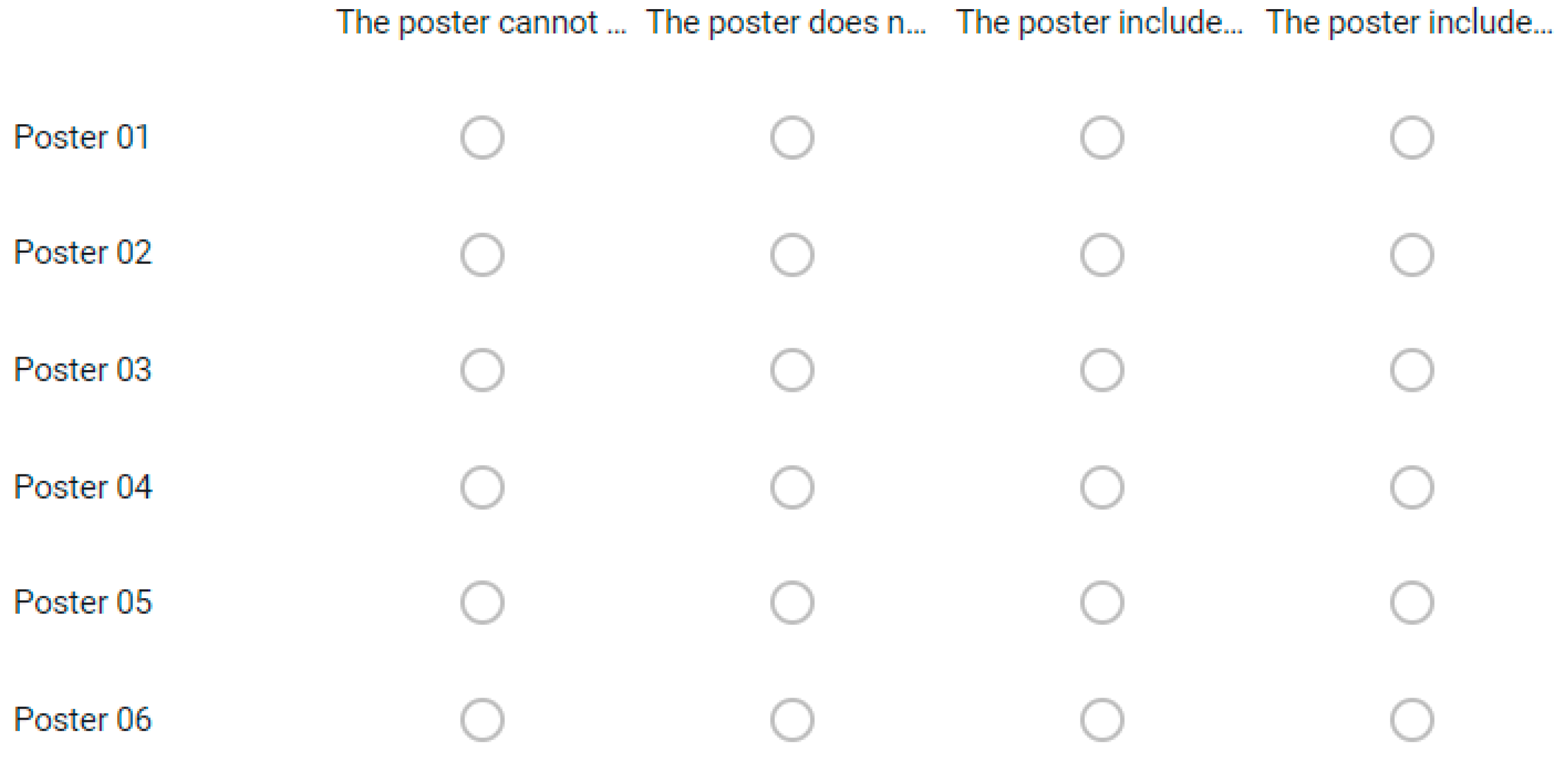

When assessing content, the following performance options were given: “1. The poster cannot be considered a scientific poster because it does not include any sections nor information expected in a scientific poster”, “2. The poster does not include all the sections expected nor they are informative enough”, “3. The poster includes all the sections expected in a scientific poster, but they are not informative enough”, and “4. The poster includes all the sections and information expected in a poster.” Figure 4 shows the results for this item.

Figure 4.

Content assessment.

Partial disagreement is found for all posters but poster 2, where there are three different ratings. It is especially noteworthy that these include the lowest and highest possible ratings, which means that while one instructor considers that, with respect to its content, the poster cannot be considered a scientific poster, another instructor thinks that it includes all the sections and information that could be expected in this genre. Agreement is found in the higher mark in posters 1 and 5, while instructors agreed on giving a lower mark in posters 3, 4 and 6.

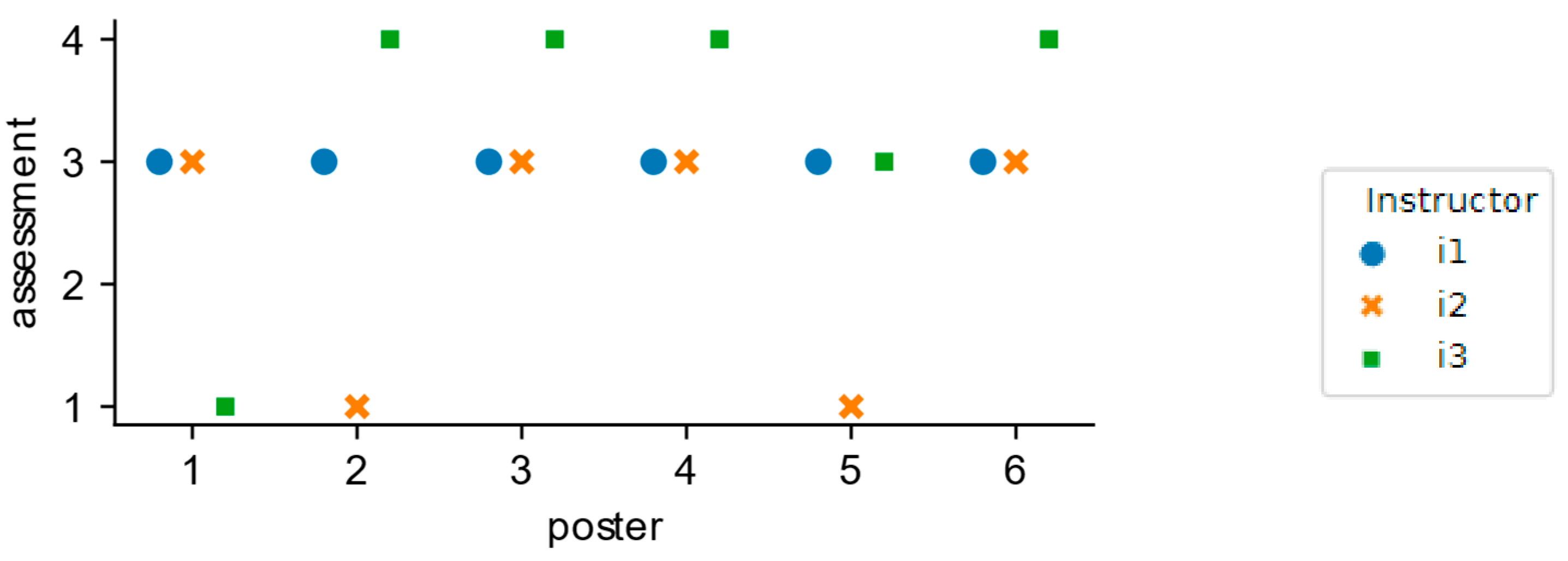

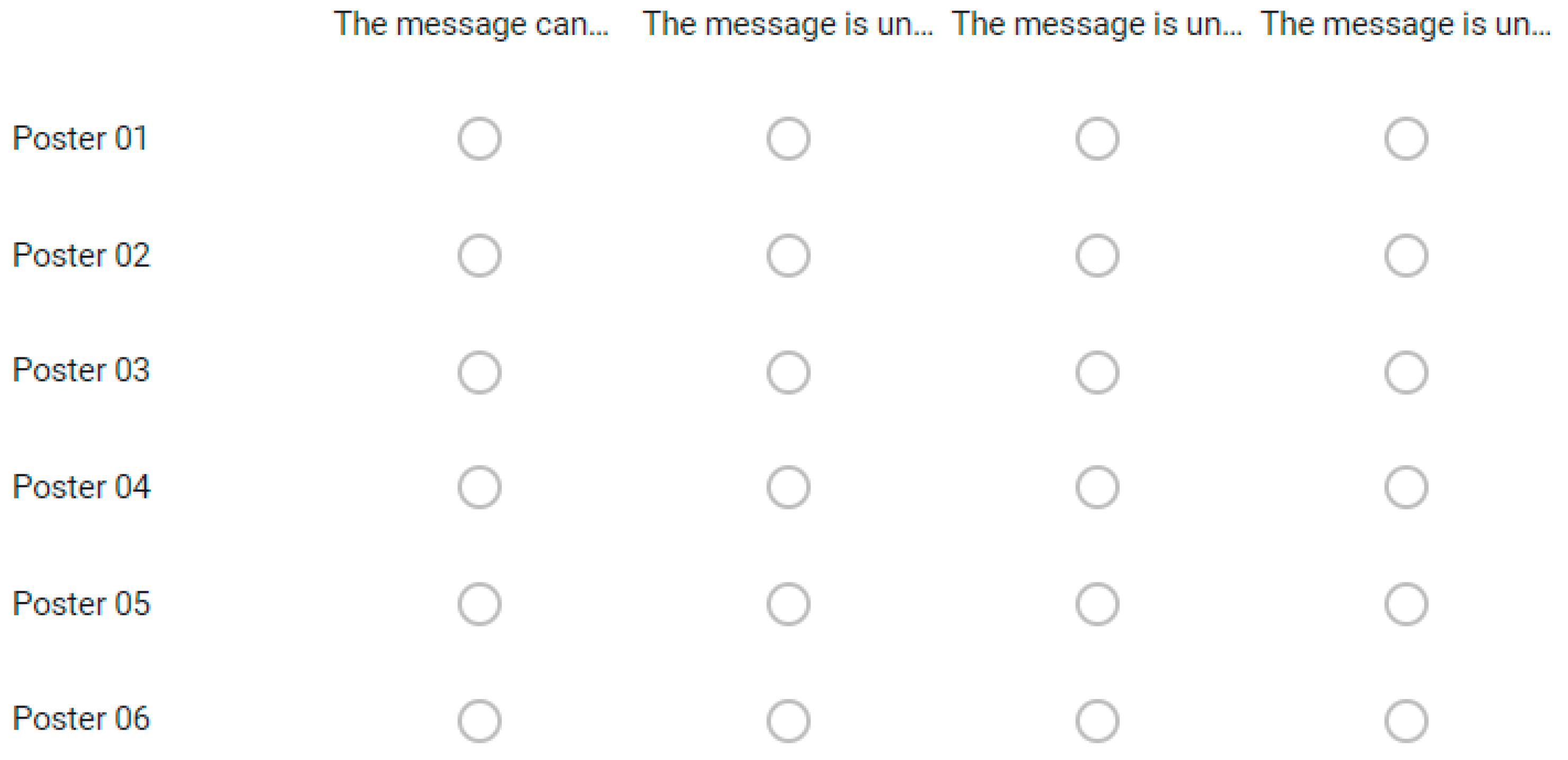

Finally, the assessment involved English expression. The options were “1. The message cannot be understood”, “2. The message is understood, but the style is not adequate and there are grammar and vocabulary mistakes”, “3. The message is understood, but the style is not adequate or there are grammar and vocabulary mistakes”, and “4. The message is understood, the style is adequate and there are no grammar or vocabulary mistakes.” The answers are presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

English assessment.

Some agreement can be found in posters 2 and 3, while three different ratings were given to posters 4 and 5. However, instructors showed total agreement in posters 1 and 6.

4. Discussion

This section presents some comments on possible reasons behind the results and connections to previous research in the field. The section is organised in the same fashion as the previous one.

4.1. Material Design and Creation

Regarding results from the discussion group formed to evaluate the materials designed and created, it can be said that they were highly favourable. The module created is short enough to be compatible with school calendars and students’ schedules, but it is informative and useful enough to produce positive results in students’ performance.

Additionally, during the online discussion session, it was observed that international students do probably share some basic common knowledge about the use of online educative platforms, which makes it easy to design digital materials that can be accessed and used by students later. Students may also feel comfortable when understanding how a course may work, what they may be expected to do, and how to manage the resources of which the course makes use. Additionally, they are usually familiar with synchronous and asynchronous online teaching.

The most difficult part in designing such an activity is scheduling it; that is, finding a specific, adequate, and convenient schedule for synchronous sessions with students from different institutions. In this case, the module designed requires two online sessions which are preceded by online, individual, asynchronous work, and are interwoven with optional group asynchronous work. That means that students must devote time to the activity over several weeks and, if needed, find a time to meet with the other members of their groups, as well as be available for the synchronous sessions. Since the first and second terms do not start and end at the same time in every institution, if this module were to be implemented with international students, they might find it difficult to enroll if the schedule does not suit their ordinary classes.

To finish, it must be said that some typos were observed in the materials during their implementation, so they will be revised before further use.

4.2. Internationalisation

As mentioned in Section 2, most students participating in the study were in their second year of the degree. However, students usually go to study abroad in their third or fourth years, so it was expected that most of them had no previous experience studying abroad or cooperating with foreign students. Those who had some mostly referred to summer camps or exchange experiences in their high school years. Since they were taking the optional course “English applied to Optics and Optometry”, students were also expected to have an interest in languages or value the importance of speaking a foreign language in their personal and professional lives. Additionally, some foreign students actually visit these students’ university, so they might have also had previous experiences with international students in their own university.

Despite the convenience of attending courses from foreign universities online, most students preferred to attend those courses on-site, which means travelling to a foreign country and living there for at least a semester. This may be related to students’ interest in English as a foreign language and thus indicate that they would like to be really immersed in a foreign culture as a personal experience and as a way to improve their language skills. However, students thought that they would be more willing to take online foreign courses if they had a classmate participating in their courses that way, so their initial reticence to do so may be due to their current unfamiliarity with the procedure, since this practice had not been carried out previously in their degree.

Students’ feeling that universities have different expectations regarding them may be based on their previous international experiences. However, the most important point in this question is that students’ thinking so may have an influence on their self-confidence regarding their performance in a foreign university or on their choices when deciding which university or country to visit if taking a semester or a year abroad.

4.3. Research and Language Skills

Students agree on the importance they give to research nationally and internationally and in their degree, and they had actually been asked to conduct research during their university studies. However, it is important to highlight that most of them had not had any previous training in conducting research. That means that students are asked to do something they have not been properly trained to do, and this may have an impact on their performance.

This point and the one discussed in the previous section regarding students’ thoughts on institutions having different expectations about students show the need for the creation of homogeneous training on how to conduct research at university. Regarding the success of this pilot experience, it can be said that, taking into account that the study carried out here involved half an hour of theoretical, video-based training and a total of 4 h of in-class work, the improvement in students’ confidence regarding how prepared they were to conduct research and communicate their results is noteworthy: an increase from 52% to 87%. This means that this type of training may be suitable for university students and that it can be carried out in a context combining on-site and online students and including a workload of asynchronous and synchronous tasks.

4.4. Students’ Posters Assessment

The evaluation has shown a high degree of disagreement in the instructors’ criteria. For most assessment items and posters, instructors did not meet in a unified rating (which was only observed 4 times), but they usually provided two different ratings (18 times) and even three different ratings (8 times). Therefore, partial agreement is the most common result. There was no particular trend observed in the matching of the criteria; that is, when partial agreement was found, it was not always between the two same instructors. This seems to point to very different criteria in instructors’ assessment, which indicates that further investigation is needed to confirm whether this lack of consistency may be common among different institutions or occasionally found in this specific case.

To finish with the discussion of the results, it must be noted that the resources needed to carry out the experiment, as mentioned in Section 2, included a learning management system. To provide support for this experiment, it would be necessary that this system allows the implementation of the activities described, including presentation and storage of audio-visual materials, integrated activities for individual and group synchronous and asynchronous work (e.g., forums, tests or quizzes, live chats and videoconference sessions among students, etc.), online synchronous sessions with the instructor for the class sessions, and assessment of students’ assignments by multiple instructors.

5. Conclusions

This study has dealt with the possibilities that blended learning offers in the context of higher education instruction open to international students due to its flexibility regarding the location of the instructors and students, synchronous and asynchronous teaching and learning time, and the grouping of students (individual and group work). As key aspects in the use of blended learning with internationalisation purposes, educational materials and courses should be designed with shared international perspectives; in addition, it is necessary to cover topics and skills that international students can benefit from; and finally, it is also important that students’ work is assessed with shared criteria that ensure an internationally accepted level of performance.

For these reasons, this paper has presented an experiment based on the planning, design, creation, and implementation of some basic training organised in a short module on how to conduct research and how to make a scientific poster targeting 30 students mostly in their 2nd year, but also in their 3rd or 4th, from the BSc in Optics and Optometry from the Complutense University of Madrid. Inter-university cooperation was received for the first phase of the study, consisting of the design of the materials and the module, as well as for part of the second phase (the implementation of the module), specifically in the assessment of students’ work to compare instructors’ criteria in their evaluations.

The design of the module as consisting of a set of videos about scientific research and scientific posters with a total length of about half an hour can be evaluated as good and adequate for international use, since the results regarding the quality and usefulness of the contents were entirely positive. In order to have wider cooperation of instructors and students from other universities, it would be necessary to cope with making the implementation compatible with other instructors’ ordinary duties, finding a place for these activities inside an existing course or designing it as a stand-alone module with official recognition, and institutions’ calendars.

Additionally, the results revealed that students would be more likely to join online courses from foreign universities if they were already familiar with that option, for example with the online attendance of visiting students to their courses. Therefore, more promotion would be necessary to increase students’ willingness to enroll and participate.

Since this exploratory study required students to work individually and in groups, synchronously and asynchronously, and online and on-site, it can be said that blended learning was successfully tested to a great extent. However, the training can be enriched with additional activities and materials to improve it pedagogically, as well as with additional or different procedures to ensure the suitability for larger groups of students (such as peer evaluation or number of members per group).

The experiment also involved the sharing of international views on conducting research at the bachelor level, thanks to the cooperation of contributor partners in the assessment of students’ work. They had to mark five parameters of the posters according to four performance levels each. In their evaluations, instructors tended to disagree more often than not. This points to very heterogeneous criteria in their assessment and shows the importance of further research and work on this issue.

Bearing in mind that conducting research can be considered key, cross-disciplinary knowledge to university studies and that research is largely shared internationally, the design of a series of brief courses addressing key issues about conducting research at higher education institutions can be proposed. These series would be offered by European institutions after being approved to ensure that all students receive similar instruction and therefore their research meets international criteria. In addition, the use of an internationally shared learning management system that meets the needs of the instruction designed should be considered as well. In light of the results and conclusions presented here, it can be said that future education guidelines should benefit from addressing issues such as the compatibility of calendars among universities and institutions, the promotion and visibility of common assessment criteria, and students’ duties to make students more confident regarding their performance to study internationally, and to increase students’ awareness of international educational options and enrolment in educational activities.

It must be remembered that this study was only exploratory in nature. For this reason, the number of participants, including both instructors and students, was limited. Consequently, the results, although promising, cannot be generalised and applied to other contexts and profiles different from those specifically dealt with here until a wider sample is analysed. However, they point to an interesting research line that deserves closer attention and should be further studied to find general patterns across Europe that lead to possible improvements in higher education at an international level.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.M.-L. and R.B.-V.; methodology, N.M.-L. and R.B.-V.; software, N.M.-L. and R.B.-V.; validation, N.M.-L. and R.B.-V.; formal analysis, N.M.-L. and R.B.-V.; investigation, N.M.-L. and R.B.-V.; resources, N.M.-L. and R.B.-V.; data curation, N.M.-L. and R.B.-V.; writing—original draft preparation, N.M.-L.; writing—review and editing, N.M.-L.; visualization, N.M.-L.; supervision, N.M.-L.; project administration, N.M.-L. and R.B.-V.; funding acquisition, N.M.-L. and R.B.-V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Union as part of the Erasmus+ project 606692-EPP-1-2018-2-FR-EPPKA3-PI-POLICY (OpenU).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Feedback on Short Module Design

Regarding the collaboration for the design of the module

- What is your general evaluation of the collaboration?

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| Very bad | Very good |

- 2.

- Were the communication means adequate? (E-mail, Google Meet meeting, online questionnaire, files shared through Google Drive)

- □

- Yes

- □

- No

- 2.1.

- If you said No, why? (open answer)

- 3.

- What benefits were obtained through the collaboration? (open answer)

- 4.

- What difficulties were found in the collaboration? (open answer)

- 5.

- What aspects can be improved in the future? (open answer)

Regarding the design of the module

- 6.

- Is the topic (research skills and the use of English as a foreign language) interesting in the context of university students in your opinion? (open answer)

- 7.

- Do you think the materials created provide enough information to do the task (carry out some research and design a scientific poster), taking into account the different background students have at different universities?

- □

- Yes

- □

- No

- 7.1.

- If you said No, why? (open answer)

- 8.

- Can you provide some feedback about the videos? (open answer)

- 9.

- Do you have any additional comments to improve the proposal? (open answer)

Appendix B. Pre-Test on Internationalisation

- How old are you?

18/19/20/21/22/23/24/25+

- 2.

- In which year of you degree are you?

1st year/2nd year/3rd year/4th year/5th+ year

- 3.

- Have you ever studied abroad?

- □

- Yes, official education at university.

- □

- Yes, official education in high school.

- □

- Yes, private courses in the summer.

- □

- Yes, other.

- □

- No.

- 3.1.

- (If the answer was No) Would you like to study abroad?

- 3.2.

- (If the answer was Yes) Why did you do it?

- 3.3.

- (If the answer was Yes) Would you like to do it again?

- 4.

- What do you think the benefits of studying abroad are?

- 5.

- What do you think the challenges of studying abroad are?

- 6.

- Think of the possibility of studying some courses of your degree abroad. What would you prefer: to go to a foreign country to study there or to take courses from a foreign university but staying in your own country (i.e., taking the courses online)?

- □

- Go abroad and attend the foreign university courses on-site.

- □

- Stay in my country and attend the foreign university courses online.

- 7.

- Have you cooperated with international students before with academic purposes (e.g., visiting students in your degree)?

- □

- Yes

- □

- No

- 7.1.

- (if the answer was No) Would you like to cooperate with international students for academic purposes?

- □

- Yes

- □

- No

- 8.

- Do you think that what universities expect from students in foreign universities is different from what your university expects from you, academically speaking?

- □

- Yes

- □

- No

- 8.1.

- (if the answer was Yes) In which ways is it different? (open answer)

Appendix C. Post-Test on Internationalisation

- How old are you?

18/19/20/21/22/23/24/ 25+

- 2.

- In which year of you degree are you?

1st year/2nd year/3rd year/4th year/5th+ year

- 3.

- Do you think that working with international students for your university assignments increases your interest in internationalisation?

- □

- Yes

- □

- No

- 4.

- Imagine some of your classmates are foreign students who attend courses from your degree online. Would you be more likely to take a course from that university if you have contact with these students (e.g., they can tell you about the courses you are interested in, the teachers, the assignments, etc.)?

- □

- Yes

- □

- No

Appendix D. Pre-Test on Research and EFL Skills

- How old are you?

18/19/20/21/22/23/24/25+

- 2.

- In which year of you degree are you?

1st year/2nd year/3rd year/4th year/5th+ year

- 3.

- Have you studied at a foreign university?

- □

- Yes

- □

- No

- 4.

- Do you think that doing research is important as a student in your degree?

- □

- Yes

- □

- No

- 5.

- Do you think that doing research is important for university students in general (in national and international universities)?

- □

- Yes

- □

- No

- 6.

- Have you been asked to do research at any point during your studies in the degree?

- □

- Yes

- □

- No

- 7.

- Have you had any specific training on how to do research during your degree?

- □

- Yes

- □

- No

- 8.

- Imagine you are taking a course from a foreign university, and they ask you to do some assignment that requires doing research. Do you think that you are prepared to carry out the research and communicate your results?

- □

- Yes

- □

- No

- 9.

- Do you know what research is, what the types of research are and what the elements in research are?

- □

- Yes

- □

- No

- 10.

- Do you know how to design and write a scientific poster?

- □

- Yes

- □

- No

Appendix E. Post-Test on Research and EFL Skills

- How old are you?

18/19/20/21/22/23/24/25+

- 2.

- In which year of you degree are you?

1st year/2nd year/3rd year/4th year/5th+ year

- 3.

- Do you know what research is, what the types of research are and what the elements in research are?

- □

- Yes

- □

- No

- 4.

- Do you know how to design and write a scientific poster?

- □

- Yes

- □

- No

- 5.

- Do you think your knowledge about research and scientific communication has improved after completing the project?

- □

- Yes

- □

- No

- 6.

- Imagine you are taking a course from a foreign university, and they ask you to do some assignment that requires doing research. Do you think that you are prepared to carry out the research and communicate your results?

- □

- Yes

- □

- No

- 7.

- Do you think that working with research material in a foreign language and producing a poster and a presentation in that language has helped you improve your foreign language linguistic skills?

- □

- Yes

- □

- No

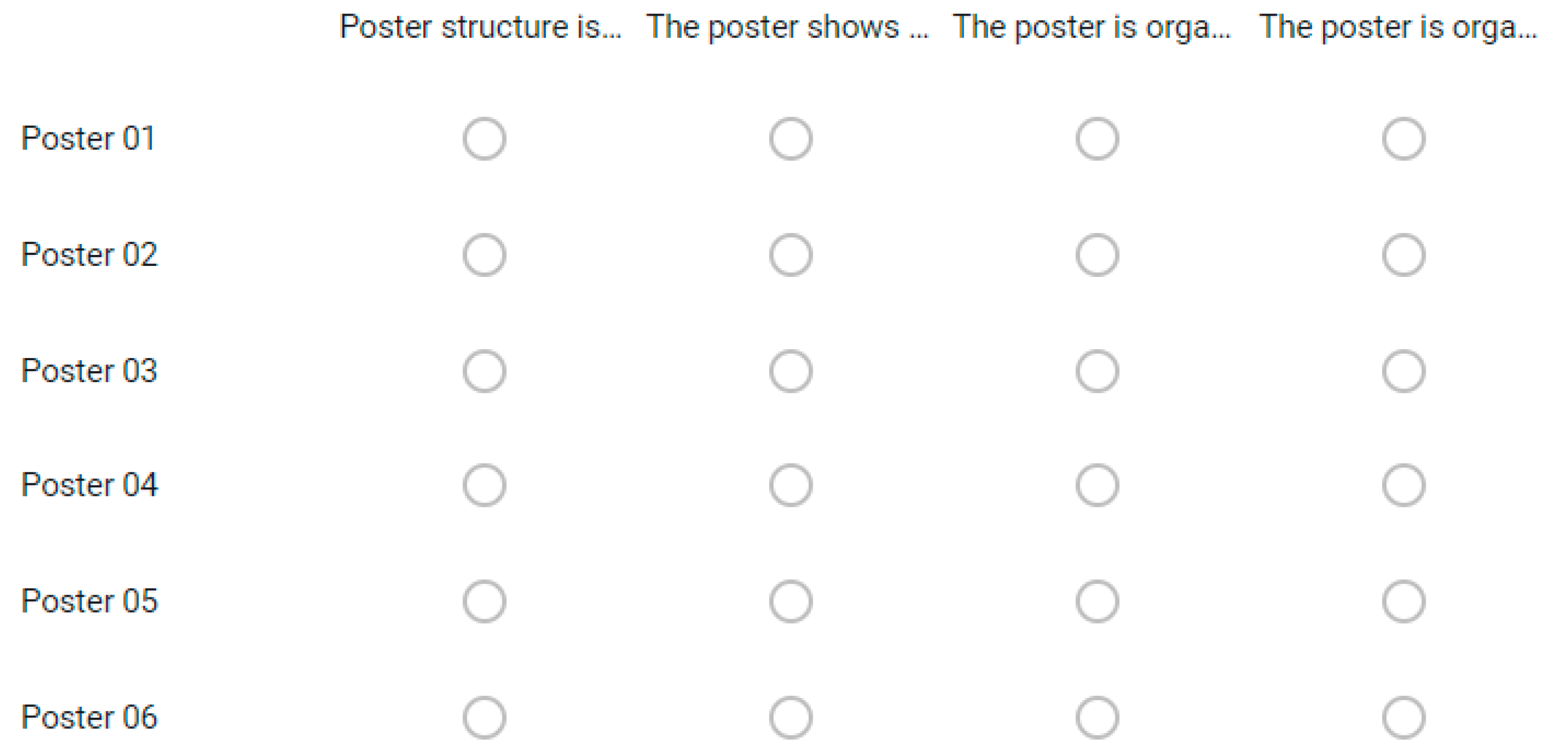

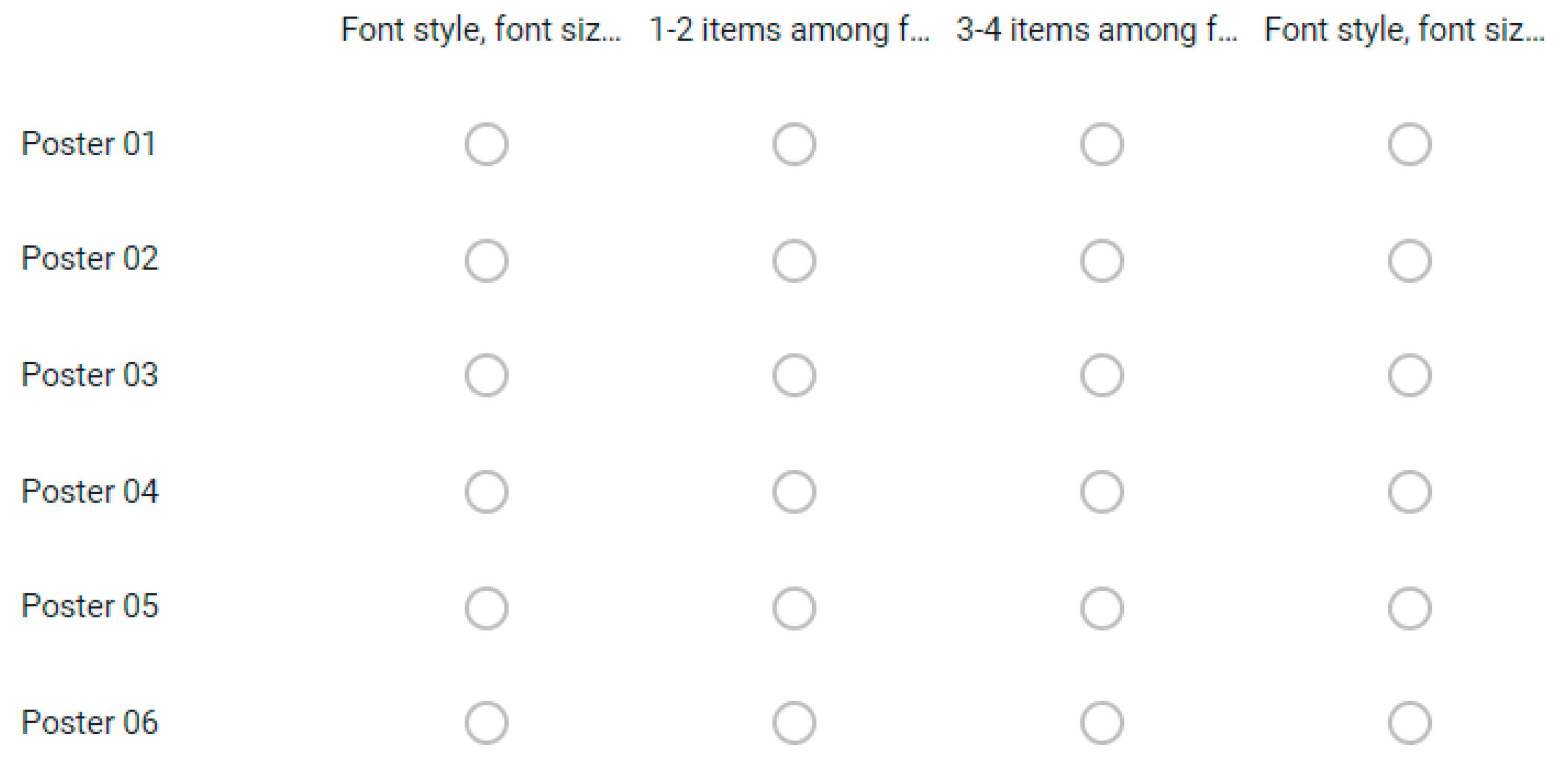

Appendix F. Rubric for the Assessment of Students’ Scientific Posters

- Layout

- 2.

- Further comments on Layout. Please indicate the number of the poster if you want to refer to any of them specifically. (open question)

- 3.

- Visual appearance

- 4.

- Further comments on Visual appearance. Please indicate the number of the poster if you want to refer to any of them specifically. (open question)

- 5.

- Graphics

- 6.

- Further comments on Graphics. Please indicate the number of the poster if you want to refer to any of them specifically. (open question)

- 7.

- Content

- 8.

- Further comments on Content. Please indicate the number of the poster if you want to refer to any of them specifically. (open question)

- 9.

- English

- 10.

- Further comments on English. Please indicate the number of the poster if you want to refer to any of them specifically. (open question)

- 11.

- Further comments on the posters. You may mention any issues that you think are relevant but have not been addressed in the previous questions. (open question)

References

- Bryan, A.; Volchenkova, K.N. Blended learning: Definition, Models, Implications for higher education. Bull. South Ural State Univ. Ser. Educ. Sci. 2016, 8, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrastinski, S. What do we mean by blended learning? TechTrends 2019, 63, 564–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, C.R. Blended learning systems: Definition, current trends and future directions. In The Handbook of Blended Learning: Global Perspectives, Local Designs; Bonk, C.J., Graham, C.R., Eds.; Pfeiffer: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2006; pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Garrison, D.R.; Kanuka, H. Blended learning: Uncovering its transformative potential in higher education. Internet High. Educ. 2004, 7, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaidullin, R.N.; Safiullin, L.N.; Gafurov, I.R.; Safiullin, N.Z. Blended learning: Leading modern educational technologies. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 131, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, M.; Dalgarno, B.; Kennedy, G.E.; Lee, M.J.; Kenney, J. Design and implementation factors in blended synchronous learning environments: Outcomes from a cross-case analysis. Comput. Educ. 2015, 86, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raes, A.; Detienne, L.; Windey, I.; Depaepe, F. A systematic literature review on synchronous hybrid learning: Gaps identified. Learn. Environ. Res. 2020, 23, 269–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkroost, M.J.; Meijerink, L.; Lintsen, H.; Veen, W. Finding a balance in dimensions of blended learning. Int. J. E-Learn. 2008, 7, 499–522. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, E.; Park, S. How are universities involved in blended instruction? J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2009, 12, 327–342. [Google Scholar]

- Borup, J.; Graham, C.R.; Velasquez, A. The use of asynchronous video communication to improve instructor immediacy and social presence in a blended learning environment. In Blended Learning Across Disciplines: Models for Implementation; Kitchenham, A., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2011; pp. 38–57. [Google Scholar]

- Awodeyi, A.F.; Akpan, E.T.; Udo, I.J. Enhancing teaching and learning of mathematics: Adoption of blended learning ped-agogy in University of Uyo. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2014, 3, 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Chaoqun, W. Implementation of Asynchronous Interactive Learning activities in a blended teaching environment and the evaluation of its effectiveness. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. (IJET) 2022, 17, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, R.A.; Kamsin, A.; Abdullah, N.A. Challenges in the online component of blended learning: A systematic review. Comput. Educ. 2020, 144, 103701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapitan, L.D., Jr.; Tiangco, C.E.; Sumalinog, D.A.G.; Sabarillo, N.S.; Diaz, J.M. An effective blended online teaching and learning strategy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Educ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 35, 116–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Chen, J.; Tai, M.; Zhang, J. Blended learning for Chinese university EFL learners: Learning environment and learner perceptions. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2021, 34, 297–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, C.P.; Ramirez, R.; Smith, J.G.; Plonowski, L. Simultaneous delivery of a F2F course to on-campus and remote off-campus students. TechTrends 2010, 54, 34–40. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M. Blended learning in a university EFL writing course: Description and evaluation. J. Lang. Teach. Res. 2013, 4, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, R. Blended learning in higher education: Trends and capabilities. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2019, 24, 2523–2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.; Hill, J. Defining the nature of blended learning through its depiction in current research. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2019, 38, 383–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, A. Counseling International Students: Clients from around the World; Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Poyrazli, S.; Grahame, K.M. Barriers to adjustment: Needs of international students within a semi-urban campus community. J. Instr. Psychol. 2007, 34, 28–45. [Google Scholar]

- Durkin, K. The adaptation of East Asian masters students to western norms of critical thinking and augmentation in the UK. Intercult. Educ. 2008, 19, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.J.; Levesque-Bristol, C.; Yough, M. International students’ self-determined motivation, beliefs about classroom assessment, learning strategies, and academic adjustment in higher education. High. Educ. 2021, 81, 1215–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellstén, M.; Prescott, A. Learning at university: The international student experience. Int. Educ. J. 2004, 5, 344–351. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade, M.S. International student persistence: Integration or cultural integrity? J. Coll. Stud. Retent. Res. Theory Pract. 2006, 8, 57–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, E.; Burney, S. Racism, eh? Interactions of South Asian students with mainstream faculty in a predominantly white Canadian university. Can. J. High. Educ. 2003, 33, 81–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtonen, M.; Olkinuora, E.; Tynjälä, P.; Lehtinen, E. “Do I need research skills in working life?”: University students’ motivation and difficulties in quantitative methods courses. High. Educ. 2008, 56, 599–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, W.; Dash, D.P. Research skills for the future: Summary and critique of a comparative study in eight countries. J. Res. Pract. 2013, 9, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ain, C.T.; Sabir, F.; Willison, J. Research skills that men and women developed at university and then used in workplaces. Stud. High. Educ. 2019, 44, 2346–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, L.; Jansen, S. Working from the Same Page: Collaboratively Developing Students’ Research Skills Across the Univer-sity. Counc. Undergrad. Res. Q. 2016, 37, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauschenbach, I.; Keddis, R.; Davis, D. Poster development and presentation to improve scientific inquiry and broaden effective scientific communication skills. J. Microbiol. Biol. Educ. 2018, 19, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt-Harsh, M.; Harsh, J.A. The development and implementation of an inquiry-based poster project on sustainability in a large non-majors environmental science course. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 2013, 3, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, N. A poster assignment connects information literacy and writing skills. Issues Sci. Technol. Librariansh. 2015, 80, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).