Abstract

Emotional Intelligence (EI) is considered a fundamental variable for a person’s adequate psychosocial adjustment. In education, its importance transcends the level of interpersonal relationships, and has been proposed as a variable that somehow influences academic performance, although there is controversy about whether its effect is direct or, rather, an intermediate variable. The present research analyses, from a sample of 327 students (52.6% female and mean age = 14.5), the relationship of EI with respect to the knowledge and management of oral communication and reading meta-comprehension strategies, which should directly affect different educational outcomes. In order to assess both the direct and indirect effects of these variables, a Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM) approach has been proposed, due to its versatility and the possibility of jointly analysing reflective and formative measures. The results show that EI indirectly affects reading self-concept and reading comprehension, as it is involved in the management and handling of both effective oral communication and reading meta-comprehension strategies.

1. Introduction

In the field of education, it is common to use tests that attempt to assess both reflective psychological constructs (e.g., emotional intelligence) and formative constructs related to learning and academic achievement. Although the reflective or formative nature of the measures is rarely addressed [1,2,3], this differentiation is a fundamental issue in choosing the most appropriate statistical model for assessing the validity of evidence regarding the constructs measured and their relationships.

In a reflective measure such as emotional intelligence (EI), it is assumed that there is a latent variable in which the items are imperfect indicators that are directly deduced from the latent variable, which means that a larger number of indicators usually leads to a more reliable estimate of the latent variable. This requires that the indicators have an adequate discrimination value (i.e., a high relationship with the latent variable), which entails a decrease in measurement error.

In a formative measure, the indicators or items are chosen by the researcher for their own interest in relation to a particular learning outcome. For example, in a measure of reading meta-comprehension, it may be of interest to know whether the person knows and uses strategies such as underlining parts of the text, marking main ideas or other strategies that improve comprehension. Also, in order to assess oral communication skills, the use and knowledge of various strategies can be investigated. Such constructs can be conceptualised as formative, as the constructed variable depends critically on the items chosen by the researcher and, therefore, a different set of strategies necessarily leads to a different constructed latent variable.

In this study, we conducted a Partial Least Squared Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) [4] as an analysis procedure, which allows both formative and reflective variables to be analysed jointly. More specifically, we showed how to set up a reflective-formative model and the consequences derived from this analysis. To this end, the model combines a reflective psychological variable for the assessment of EI (measured by the Trait Meta-Mood Scale—TMMS-24 [5]), one of the most widely used assessment measures of EI, and two formative variables on different strategies taught in the educational environment: strategies for oral communication (the Test of Self-Perceived Oral Competence—TSOC) [6] and strategies for reading meta-comprehension (Revised Metacognitive Awareness of Reading Strategies Inventory—MARSI-R) [7]. For these reflective and formative latent variables, the predictive capacity is analysed with respect to two criterion variables, reading skills (self-perceived measure) and reading comprehension assessed by a test corresponding to the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) [8].

There is controversy about the role of EI in academic achievement, with results that have observed a relationship with academic success [9,10], and others in which no such relationship was observed [11,12,13]. These contradictory results highlight the object of study and the variables involved, making it necessary to implement methods of analysis that allow the problem evaluation in its complexity while respecting the formative or reflective nature of the variables involved.

PLS-SEM, due to its exploratory nature, is designed to model complex relationships that maximise the predictive capacity of the models, making it a suitable tool to try to explain how academic performance, specifically in the area of reading comprehension, is influenced by IE, taking into account mediating variables such as oral and reading strategies, respecting the reflective or formative nature of these variables.

We operationalize all these variables in the following sections. Finally, the model tested is justified in relation to evidence from previous studies.

1.1. Emotional Intelligence (EI)

Emotions foster the satisfaction of social functions, and contribute to the determination of a collective as a social group [14]. Previous research suggests that “emotions, like feelings, are part of what we are, personally and socially” [15]. Therefore, the importance of delving deeper into this construct has increased in the psycho–pedagogical area. Emotions are part of the human being, and one of the ways of studying them has been through EI.

In the early 1990s, Salovey and Mayer [16], inspired by earlier research by Gardner [17], coined the term EI for the first time. These authors understand EI as a new approach that goes beyond cognition, highlighting the importance of the emotional, as well as the intellectual. Thus, they define EI as the ability to perceive, know, access and generate emotions, as well as to reflect and regulate emotions that activate both emotional and intellectual growth [18].

The most commonly used instruments for the assessment of EI are self-reports. They consist of a series of short verbal statements, in which the person evaluates his or her level of emotional competences and skills. Their usefulness lies in the exercise of introspection that is carried out, which implies knowledge about intrapersonal ability. Their main drawback is that the response may be influenced by the perceptual bias of the person who is self-assessing, as well as by social desirability. Within self-reports, Salovey et al. [19] developed the TMMS, one of the first questionnaires to measure metacognition of emotional states, based on the original model of Salovey and Mayer [16]. Both the original version and the reduced 24-item version adapted to Spanish (TMMS-24) [20] are self-report measures for assessing perceived intrapersonal EI (beliefs that people hold about their ability) in three dimensions: attention to feelings, clarity and repair [5]. It is considered that a good EI can have benefits for the person, through the measurement of these three dimensions, which contribute significantly to the development of psychological well-being [16,18]: (a) attention to feelings: the ability to feel and express emotions appropriately, (b) clarity: the perception an individual has of the understanding of their own emotional states and, (c) repair: the ability to regulate moods and repair negative emotional experience.

1.2. EI and Academic Performance

Research relating EI to academic achievement yields contradictory results, as we have already noted. In Spain, Fernández-Berrocal and Extremera [20] study this relationship in students in compulsory secondary education (ESO, from its Spanish initials), and their results highlight the connections between these two constructs as a mediating effect that good emotional health exerts on performance. Pérez and Castejón [10] analyse the specific contribution of EI in predicting academic performance. The results suggest the independent contribution (i.e., a direct effect) of EI to the prediction and/or explanation of academic performance in a sample of university students. López Fernández [9] also concludes the predictive value of EI on academic performance in university nursing students. Barna and Brott, Brackett and Mayer, and Buenrostro [12,21,22] also found positive and significant correlations between socioemotional development and academic performance. Gil-Olarte et al. [23] reveal positive effects regarding the importance of EI in academic success and social development in a group of adolescents, as measured by final grades. However, other studies do not find the relationship between EI and academic achievement in university students to be significant [11,12,13]. Newsome et al. [24] also found no significant association between EI and students’ grades. Broc Cavero [25] concludes that EI is overestimated, and does not have as much relevance and influence on academic performance as other studies have indicated.

1.3. Reading Comprehension and Its Importance in Education

One of the constructs most closely related to academic success is reading comprehension [26,27,28]. Reading comprehension is a mental process, whereby meanings are generated from a text, which is integrated with the prior knowledge and personal experiences of the individuals involved [29]. Thus, reading comprehension involves generating representations of the meaning of ideas in a text, beyond eliciting the meaning of words or sentences. In this process, readers must be able not only to read and comprehend, but also to interpret and analyse the information presented in the text.

It is therefore not surprising that various institutions, both at a national level, in Spain, (e.g., using the Indispensable Knowledge and Skills tests or Conocimientos y Destrezas Indispensables, CDI tests, from the acronym in Spanish) and at an international level (e.g., using the PISA tests) have focused on identifying students’ reading comprehension levels.

The PISA test was designed to establish what young people know and are able to do at the end of ESO in the areas of science, reading and mathematics. In the area of reading comprehension, the PISA test includes three types of texts: continuous texts, discontinuous texts and mixed texts, which can include different formats, such as literary, informational and opinion texts. In particular, the PISA test focuses on measuring students’ ability to locate relevant information, integrate literal information from different texts, generate inferences, assess the quality and credibility of information, reflect on text content and form, and detect and manage intertextual conflict [30]. This test has been used in several studies [31,32], which is evidence of its impact on research on reading comprehension assessment.

1.4. Reading Meta-Comprehension Strategies and Reading Self-Efficacy

As mentioned above, one of the variables traditionally most related to reading comprehension is the ability to implement reading strategies aimed at the comprehension, analysis and evaluation of texts [33,34]. Numerous studies have been carried out to identify the reading comprehension strategies used by students [35,36,37] and the positive results in text comprehension if they are adequately trained [38].

The assessment of reading comprehension strategies is usually carried out through self-reports [39], one of the best-known instruments being the Metacognitive Awareness of Reading Strategies Inventory (MARSI) [40] and its shorter version, the MARSI-R [7,41]. This instrument focuses on three distinct but related types of strategies: global reading strategies, which focus on the overall comprehension of a text; problem solving strategies, which focus on strategies that are implemented when a text is difficult to read; and support reading strategies, which involve note-taking or the use of support materials.

Another relevant variable for academic success, in this case in reading comprehension, is students’ perceived self-efficacy in this area [42]. Self-efficacy can be described as the extent to which people perceive themselves as effective in performing certain behaviours. However, this variable is not only related to academic success but, as Zimmerman [43] points out, it is also related to students’ perceived control of strategies. According to this author, students’ control of learning strategies makes them perceive themselves as more competent, which leads to greater persistence in the task, resulting in a positive effect on performance [44].

Thus, two relationships can be established and should be considered when talking about reading self-perception. On the one hand, the relationship between students’ self-perception and the control they perceive when applying strategies in a task and, on the other hand, the relationship that this self-perception has, in itself, with reading performance. Much work has been carried out to identify the relationship between reading self-perception and the use of reading comprehension strategies [41]. Thus, Naseri and Zaferanieh and Li and Wang (2010) [45,46], using self-reported reading strategy questionnaires, identified significant positive relationships with reading self-perception. However, it should be noted that, although a strong relationship is observed between perceived self-efficacy and the self-reporting of reading strategies, these may also be accentuated by the self-report nature of both variables. On the other hand, Naseri and Zaferanieh [45] have also identified relationships between reading self-perception and reading achievement, as have other authors [32,47].

1.5. Oral Communication Strategies

A variable closely related to reading comprehension, which affects academic performance is that of oral communication strategies. The development of communication and language skills (listening, speaking, reading and writing) is fundamental in all educational contexts and levels, and can therefore be considered part of what has been understood as academic achievement. Their value lies not only in the possibility they offer to demonstrate the knowledge acquired in the classroom, but also in the fact that they are very powerful psychological tools that enable knowledge to be elaborated and transformed, learning to be optimized, and reflective thinking to be developed, among other aspects [48,49,50].

The teaching and learning of oral language should be a priority in formal educational contexts, as its mastery has personal, professional and social implications, in line with the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages [51], which attaches fundamental importance to oral language competence.

Being competent in oral language enables learners to produce complex, coherent, cohesive and contextually appropriate oral texts, while at the same time equipping them with the ability to request information, argue, ask for clarification, refute, synthesise, summarise, reflect on their own language, etc., with different interlocutors and for different purposes [52,53,54].

Among the few instruments that exist to assess knowledge and use of oral communication strategies, some of them link self-perceived oral communicative competence with aspects related to the anxiety of speaking a foreign language or a language that is not one’s own, in multilingual contexts [55]. Studies have also been carried out on the language itself, suggesting the use of the Speech Skills Self-Efficacy Scale proposed by Demir [56] and designed to assess the use of oral communication strategies.

An ambitious paper by Croucher et al. [57] reviews the research carried out using the questionnaire that was published in 1988 by McCroskey and McCroskey, to self-assess communicative competence in university contexts. Croucher et al. [57] indicate that, despite being designed for this educational context, it has been used at other levels, and conclude that only four studies have conducted a reliability analysis of the test since 2000 and that, although it has been used in 12 different countries, statistical analyses have shown little evidence of construct validity.

Author [6] developed the TSOC, an instrument for self-perception of oral competence, which assesses five key dimensions: (1) Interaction Management; (2) Multimodality Prosody; (3) Textual Coherence and Cohesion; (4) Argumentative Strategies; (5) Lexicon and Terminology. In this validation study with compulsory secondary education students, adequate reliability (between 0.85 and 0.88) and good fit with the correlated five-factor structure were observed. In terms of evidence of construct validity in relation to other variables, it was observed that the TSOC correlated with reading meta-comprehension strategies, assessed using MARSI-R [7]. Although these are different skills, these results reveal a connection between the dimensions that constitute communicative competence (i.e., oral language and reading), which has not gone unnoticed in the curricula of educational laws in various countries [51,58]. The link between oral proficiency and reading comprehension was highlighted by Clarke et al. [59] in a study in which they found that listening comprehension is the main predictor of reading comprehension, and that this relationship increases with age.

1.6. EI in Relation to Oral Proficiency

Some studies link children’s EI and language proficiency, and, in some cases, the latter is included in the former [60]. The authors consider that the multiple components that include both competences and their relationships have not been sufficiently studied. The results of their study with 10-year-old schoolchildren showed strong positive correlations between language competence and EI, ranging between r = 0.12 and r = 0.45. In particular, receptive vocabulary and literacy were closely related to emotional knowledge. A confirmatory factor analysis revealed that there is a common general ability factor for language competence and EI. While the authors make a strong case for explaining these correlations, it is important to note that none of the skills included in language competence focus on the pragmatic aspects of language.

Other authors have also focused on the relationships between these competencies at early ages [61], and specifically on the extent to which families use emotional language and talk with children about their experiences, as a way of explaining how early language development may contribute to emotional regulation skills. According to the authors, the separate analysis of language and emotional development contributes to a better understanding of how children become aware of their emotions and regulatory strategies and develop effective and appropriate emotional self-regulation. The authors point to the need to investigate how adults use a child’s emerging language skills to help them self-regulate (e.g., asking what can be done about a problem, rather than simply calming or solving it).

Lindquist et al. [62], from a constructivist approach, argue that language is a fundamental element in emotion, and is constitutive of both emotional experiences and perceptions. The authors review evidence from cognitive and developmental science, to reveal that language builds concept knowledge in humans, helping them to acquire abstract concepts such as emotional categories throughout their lifespan. The authors review different research at school age and also in adulthood, but do not present results on the adolescent stage on which the present study focuses.

Pasquier et al. [63], also with primary school children aged 9 to 11, developed a Moral and Civic Education programme, focused on the identification and expression of emotions, aimed at their comprehension and oral production. The results indicate that, although vocabulary and comprehension levels improved in both the experimental and control groups, only those who had completed the educational programme on emotions showed significantly better skills in general oral production. It is highlighted that educational practices that encourage public speaking in natural situations contribute to the development of oral language, listening and empathy skills.

1.7. The Present Study

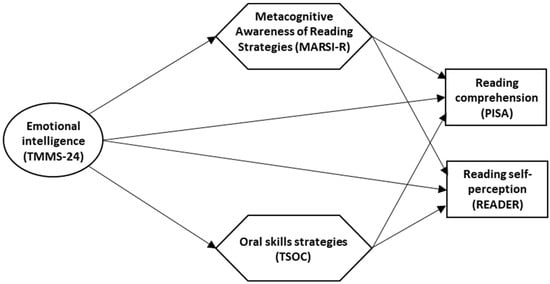

Based on the background information reviewed, the goal of this study is to evaluate the relationships between the above-mentioned variables by testing a PLS-SEM model. More concretely, we consider that the EI variable can affect both performance in reading comprehension and reading self-perception, as has been identified in previous works. However, these effects are not always clear, which could be due to the mediation of several variables. In this sense, we consider that self-reported reading and oral strategies may mediate the effect that EI has on reading comprehension and perceived self-efficacy in this domain, as can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The conceptual–structural model of the relationship between reflective (represented by an oval: TMMS-24) and formative (represented by hexagons: TSOC and MARSI-R) measures, and PISA and READER outcomes.

The model analyses the direct effects of EI (TMMS-24) on the two proposed outcomes: reading comprehension (a measure of efficacy obtained from the PISA test) and participants’ self-perception as readers (READER variable). In addition, the model allows us to evaluate the potential mediation effect of oral communication strategies (TSOC) and reading meta-comprehension strategies (MARSI-R) between TMMS-24 and the two outcomes analysed. For this purpose, the indirect and total effects of EI (TMMS-24) are also analysed. Note that, in the case of EI, the measure is operationalised as reflective, whereas the oral communication and meta-comprehension strategies are operationalised as formative. Additionally, Figure 1 does not reflect the potential relationship between the READER and PISA variables, because (1) our main objective is to analyse the direct and indirect effects of TMMS-24, MARSI-R and TSOC on each of the two outcomes separately, and (2) it is currently unclear as to what it the directionality of the relationship between READER and PISA (i.e., self-perception as readers → efficacy. or vice versa). We expand this issue in the Section 4.

To evaluate the model in Figure 1, an approach based on Confirmatory Composite Analysis [64,65] has been followed. There is a strong tradition of reducing dimensionality by means of the common factor model (i.e., Exploratory Factor Analysis and Confirmatory Factor Analysis). In the common factor model, the researcher assumes that the indicators (i.e., items) are reflective in nature. That is, each observable variable is a manifestation of a latent variable, construct or underlying concept that is the (common) cause of all the indicators it is composed of. In the common factor model, observable variables are interchangeable, as they are theoretically conceptualised as similar in meaning or content. If any indicator is removed, the construct does not change its essential meaning. In contrast, a formative construct is a weighted linear combination of observable indicators (causal indicators) [66], and therefore the indicators do not necessarily share a common cause.

The composite variables (composite or derived) are a type of variable formed by combining two or more other variables (formative or reflective), and are designed to try to capture the most important features of the data as efficiently as possible. In recent years, this approach to theoretical concepts based on composites is being increasingly legitimised by several authors, in various fields [65].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The sample consisted of 327 students (46.2% male) aged 12–17 years (mean age = 14.5, SD = 1.2) in compulsory secondary education from various schools in the Spanish metropolitan areas of Catalonia (50.5%) and Madrid (49.5%). A total of 26.9% of the participants were 1st graders (mean age = 13.0, SD = 0.19), 38.2% were 2nd graders (mean age = 14.0, SD = 0.18), 24.8% were 3rd graders (mean age = 15.1, SD = 0.42) and 10.1% were 4th graders (mean age = 15.9, SD = 0.24).

In the present study, the age of the participants is very similar to that used in previous validation studies. First, the validation study of the Spanish version of the TMMS-24 [5] was conducted with a sample of undergraduate participants who had a mean age = 22.6 years (SD = 3.9). However, in subsequent studies, the use of this instrument was also validated with the adolescent population [67] (mean age = 15.5 years, SD = 1.8). Second, in the MARSI-R validation study [7], the mean age was 13.4 years (SD = 2.0) and in the TSOC study [6] the mean age was 14.1 years (SD = 1.0). Finally, as mentioned above, the PISA test was designed to evaluate compulsory secondary education (Spanish ESO) students’ abilities in different areas.

2.2. Procedure

The educational centres were selected using a non-probabilistic sampling method (i.e., convenience sampling). The gathering of information was carried out between March and June 2021 (Madrid) and November 2021 and June 2022 (Catalonia). We contacted educational centres, and informed the principals and the teachers about the study and its objectives. Then, the parents were asked to give their informed consent for the data collection to be conducted with the students. Afterwards, teachers administered the questionnaires in the classroom (TMMS-24, MARSI-R, TSOC and PISA).

The studies, involving human participants, were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Barcelona (protocol code IRB00003099, 21 December 2020) and the Deontological Committee of the Faculty of Psychology, Complutense University of Madrid (2020/21-007, 29 October 2020). Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

2.3. Instruments

TMMS-24 [5]. This consists of 24 items, and is made up of the three dimensions of the original scale [68]: attention (ATT) to emotions (e.g., “I often think about my feelings”), clarity (CLA) (e.g., “Sometimes I can tell what my feelings are”) and repair (REP) (e.g., “I try to think good thoughts no matter how badly I feel”), each one composed of 8 items. Participants were asked to evaluate the degree of agreement with each item, using five-point ordered response categories (1 = totally disagree; 5 = totally agree) (see Table 1).

Table 1.

TMMS-24 items.

MARSI-R [7,41]. This scale has a total of fifteen item, with five items in each strategy domain or factor, and a five-point response ordered scale: 1—I have never heard of this strategy before, 2—I have heard of this strategy, but I don’t know what it means, 3—I have heard of this strategy, and I think I know what it means, 4—I know this strategy, and I can explain how and when to use it, and 5—I know this strategy quite well, and I often use it when I read. The questionnaire is composed of three scales (see Table 2): global reading strategies (GRS) (e.g., “Analyse and critically evaluate the information read”), problem solving strategies (PSS) (e.g., “Reread to make sure I understand what I am reading”), and support reading strategies (SRS) (e.g., “Underline or circle important information in the text”). The MARSI-R also includes the READER item (self-perceived reading level), used in this study as an outcome. READER has 4 ordered response categories (1—a poor reader, 2—an average reader, 3—a good reader, and 4—an excellent reader).

Table 2.

MARSI-R items.

TSOC [6]. The test consists of 22 items, and was designed to measure 5 dimensions: interaction management (IM) (3 items; e.g., “You care for your language so your words do not annoy others”), multimodality and prosody (MP) (4 items; e.g., “You are aware of how your tone of voice and volume may affect others”), textual coherence and cohesion (TCC) (6 items; e.g., “You use expressions or phrases that mark the end of your speech”), argumentative strategies (AS) (5 items; e.g., “You back what you want to say with reasons and arguments”), and lexicon and terminology (LT) (4 items; e.g., “In a conversation, words that express what you want to say come easily to mind”). This instrument presents situations or reflections on what happens when participating in conversations or oral presentations in class. The items were written to be answered using seven-point ordered response categories (1 = almost never; 7 = always) (see Table 3).

Table 3.

TSOC items.

PISA [8]. A reading comprehension test of optimal performance, with true/false responses that have been translated into zero (“incorrect”) and 1 (“correct”) values, by the research team (see Table 4). To use PISA as an outcome variable, the proportion of correct answers obtained on the different items used in the data collection process (12 items for 1st, 2nd and 3rd grade, and 16 items for 4th grade) has been calculated.

Table 4.

Access to PISA instrument.

2.4. Data Analysis

The analysis strategy used was PLS-SEM [69], using R software [70] and the seminar package [71]. This analysis strategy allows the combining of both formative and reflective measurements in the same model, estimating variable composites by a linear combination of the measurement model indicators. PLS-SEM starts by evaluating the measurement model, differentiating between formative and reflective measures, and then evaluates the structural model. The variance inflation factor was estimated to evaluate the collinearity of the formative indicators, and the significance and relevance of the estimated weights. The indicator regression weights and the loadings of the composite construct were used to assess the significance and relevance of the observable variables, respectively.

In the case of the reflective measures, we assessed the magnitude and direction of the factor loadings, the reliability of the scores (as internal consistency), the average variance extracted for all items on each construct to assess convergent validity, and the heterotrait–monotrait ratio of correlations, to assess discriminant validity. The next step consisted of evaluating the structural model by analysing the potential collinearity reflected in the correlations between each set of predictor constructs, assessing the significance and relevance of the structural relationships of the model (total, direct and indirect effects), and its explanatory and predictive power.

PLS-SEM is a non-parametric technique, and performs bootstrapping for estimating standard errors and computing 95% confidence intervals (CI). Following Streukens and Leroi-Werelds [72], we used 10,000 bootstrap subsamples.

3. Results

The sample of 327 students corresponds to the total number of students who completed all the questionnaires analysed in this paper without omitting a response. Preliminary analyses indicate that the distribution of responses to the different items that make up the three instruments analysed (TSOC, MARSI-R and TMMS-24) is moderately asymmetrical. In the case of TSOC, we obtained skewness values ranging between −0.91 and 0.08 (kurtosis between 1.83 and 3.28), for MARSI-R values ranging between −1.21 and −0.31 (kurtosis between 2.14 and 3.8), and for TMMS-24 values ranging between −1.30 and 0.42 (kurtosis between 1.10 and 1.34). Table 5 shows the correlations between all the variables analysed.

Table 5.

Correlations between variables.

3.1. Evaluation of the Measurement Model

Variance inflation factor values of 5 or above indicate critical collinearity issues among the indicators (Hair et al. recommend variance inflation factor values close to 3 or lower, as optimal) [69]. All variance inflation factor values obtained at the item level are lower than 3.

Regarding the formative measures, we tested the item weights following a two-tailed testing general convention (α = 0.05). For those weights that are not statistically significant, Hair et al. [69] recommend also inspecting the loading value, understood as the absolute contribution of a formative indicator to the construct. Therefore, two rules are followed to assess the adequacy of formative items: statistically significant weights, or weights that are non-significant but with a loading value of 0.5 or above, suggesting that the indicator makes a sufficient absolute contribution to forming the construct, even if it lacks a significant relative contribution.

Standard errors and CI were calculated by bootstrapping. It is observed that several items of the TSOC have non-significant weights (their CIs include the value zero). These are items MP1, TCC2, TCC3, TCC5, AS3, AS4, AS5, LT1 and LT3. However, in all these cases, the loadings are above 0.5 (see Table A1 in Appendix A, showing all weights and loadings obtained for the formative items). A similar situation occurs with several MARSI-R items. Items GRS2, GRS3, GRS4, PSS1, PSS5, SRS1, SRS2 and SRS5 have statistically null weights, although the loadings are above 0.5, except for items GRS4 and SRS2.

The loadings of the reflective items for the TMMS-24 measure are mostly high (around 0.7 or above), except for items ATT5 and REP7, which obtain loading values of 0.404 and 0.464, respectively (see Table A2 in Appendix A). Thus, most of the TMMS-24 items reflect sufficient levels of indicator reliability (0.708 or above; see Hair et al., 2021 [69]). The reliability values for each of the TMMS-24 subscales are shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Internal consistency reliability values of Attention, Clarity and Repair (TMMS-24).

Cronbach’s alpha is the lower bound of internal consistency [73], and the composite reliability ρc is the upper bound. The reliability coefficient ρa usually lies between these bounds, and can be considered as an approximately exact measure of construct reliability. The three subscales of the TMMS-24 obtain high levels of internal consistency, ranging between 0.86 and 0.91. On the other hand, the average variance extracted is equivalent to the communality of a construct, and reflects the degree to which the constructs converge in explaining the variance of their indicators (i.e., convergent validity). The minimum acceptable average variance extracted is 0.5 (i.e., 50% or more of the indicators’ variance that make up the construct; see Hair et al. [4]. The Repair subscale obtains an average variance extracted value slightly below 0.5 (reflecting 48.9% of the indicators’ variance). Finally, to assess the discriminant validity of the measured constructs, the heterotrait–monotrait ratio value was calculated. Following the recommendation of Henseler et al. [74], the heterotrait–monotrait ratio values found are below 0.85, reflecting the absence of discriminant validity problems.

3.2. Evaluation of the Structural Model

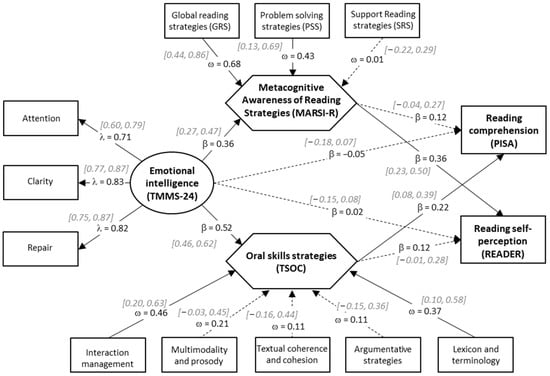

Variance inflation factor values below 3 indicate that there are no collinearity problems between constructs within the structural model. In Figure 2, the estimated PLS-SEM solution (i.e., direct effects) is shown. Non-statistically significant weights are observed for three components of TSOC (multimodality and prosody, textual coherence and cohesion, and argumentative strategies). Nevertheless, their absolute contribution to the overall TSOC composite is high, as reflected in their loadings (0.79, 0.83, and 0.77, respectively).

Figure 2.

The estimated PLS-SEM solution linking TMMS-24, MARSI-R, TSOC, READER and PISA. The 95% CI values are shown in square brackets. Dashed lines indicate non-significant direct effects.

EI (TMMS-24) has a statistically significant positive impact on TSOC (β = 0.52) and MARSI-R (β = 0.36), and a statistically null impact on READER (β = 0.02) and PISA (β = −0.05). Oral skills strategies (TSOC) have a statistically significant positive impact on PISA (β = 0.22), and a statistically null impact on READER (β = 0.12). Metacognitive awareness reading strategies (MARSI-R) have a statistically significant impact on READER (β = 0.36) and a null impact on PISA (β = 0.12).

We found two statistically significant indirect effects. These are TMMS-24 → TSOC → PISA: β = 0.114, 95% CI: [0.04, 0.21], and TMMS-24 → MARSI-R → READER: β = 0.130, 95% CI: [0.08, 0.20]. These results reflect the mediating effect of oral skills and metacognitive reading strategies in the model evaluated. EI (TMMS-24) does not reflect direct effects on outcomes, but in combination with appropriate oral and reading strategies (indirect effects), it does seem to impact reading comprehension (PISA) and reading self-perception (READER). The total effects are defined as the sum of the direct and all indirect effects of a construct over another linked construct in the model. We obtained a total effect for TMMS-24 of 0.174 on READER, and 0.111 on PISA. Both total effects are statistically significant. The main difference is that while TMMS-24 → PISA is mostly due to the TSOC mediating effect, TMMS-24 → READER is due to the MARSI-R mediating effect.

The model explanatory power is assessed from the value of the coefficient of determination (R2) and the effect size (f2). The R2 values of the endogenous constructs are moderate–weak (R2TSOC = 0.27, R2MARSI-R = 0.13). TMMS-24 reflects a high effect size on TSOC (f2 = 0.38), a relatively low one on MARSI-R (f2 = 0.15), and a practically null one on the PISA and READER outcomes. TSOC has a low effect on READER and PISA (f2 = 0.11 and 0.03, respectively), and MARSI-R has a low effect on READER and no effect on PISA (f2 = 0.11 and 0.01, respectively).

4. Discussion

Models combining reflective and formative variables are common in educational psychology. However, many of these studies do not make a correct specification of the type of variables used, which may lead to incorrect interpretations. In the present study, a predictive model with a reflective psychological variable, IE measured using TMMS-24, which is assumed to influence or explain part of the variance in the knowledge of strategies for oral-reading performance, assessed by MARSI-R and TSOC, has been proposed and analysed. In turn, the mastery of these strategies has been proposed as related to self-perception in reading competence (READER variable), and the reading comprehension assessed employing a PISA test.

By means of the PLS-SEM model proposed, it has been possible to evaluate the relationships between the variables analysed, specifying the reflective or formative nature. Thus, although initially the correlation between all the variables was found to be statistically significant at p < 0.001 (except the correlation between TMMS-24 and PISA; see Table 5), the PLS-SEM model makes it possible to go into the nature of these relationships in more depth, and these are discussed below.

Regarding the measure of EI, the reflective variable for which the TMMS-24 was applied, it was possible to observe a significant effect size (i.e., a significant shared variance with self-perceived oral competence measured using TSOC, and reading meta-comprehension strategies measured using MARSI-R).

EI measured using TMMS-24 is found to influence oral competence, with a positive linear relationship indicating a strong effect size. From a theoretical point of view, Mayer and Salovey [18] conceive EI as an ability to perceive emotions, and to access, generate and determine emotions; this, in addition, in a reflective way, makes it possible to regulate emotions that promote both emotional and intellectual growth.

Although these results are consistent with previous research [60,61,62,63,64], there are few studies that relate EI to oral language skills or oral language competence, and those that do so focus on foreign language learning, emphasising elements linked to the stress or anxiety involved in speaking in a language in which one is not an expert [75]. However, research focusing on the development of the skills to participate in a classroom conversation, to ask questions of teachers or peers, and to manage a conversation, even if it is in one’s own language, indicates that there is a strong link with emotional aspects. Probably, the reason why there are not many studies that try to identify these effects is that there is also not much literature exploring oral language competence beyond the oral presentation in groups or individual work, which usually involves prior preparation and rehearsal. On the other hand, all those activities that involve participating in a classroom discussion, managing a discussion autonomously, reflecting on the language, on one’s own oral competence, self-evaluating one’s own activity at the end of the discussion, and making decisions about what can be improved—among other aspects—involve knowledge about one’s own emotions and a degree of self-control that are closely linked to EI [60]. In fact, some of the items in the TSOC instrument are linked to EI. For example, when the student is asked to rate the degree to which “Other people clearly interpret the emotions you express with your face”, an appeal is certainly being made to emotional aspects, both in relation to oneself and to others. The same can be observed when one is asked about whether “You are aware of how your tone of voice and volume may affect others” where, in essence, the student is being asked to value the effort involved in putting oneself in another person’s shoes (empathy) to assess the degree to which a certain tone of voice may affect others (emotionally). Something similar occurs with the item “You pause so that others can follow better what you want to say”, since it requires the student to put him/herself in the place of his/her peers and try to speak slowly, to allow the peers to follow him/her. This situation is consistent with a study by Pasquier et al. [63], in which it was observed that primary school students who had completed an educational programme on emotions showed significantly better skills than the control group, in general oral production. The authors conclude that educational practices that encourage public speaking in natural situations contribute to the development of oral language and to listening and empathy skills.

However, in the present study, the relationship of EI with respect to reading level operationalized as self-perception of reading success (READER variable) and reading comprehension performance (PISA) is no longer significant, implying that there is a full mediation effect. This result could explain the discrepancies between studies on EI and its relationship with educational outcomes such as academic performance, since although it is possible to find a statistically significant relationship, the inclusion of other more directly related variables leads to a reduction in this effect [76,77].

An effect of EI on reading meta-comprehension has also been observed, although its effect size is smaller than that observed for oral communication. EI is related to students’ ability to self-regulate when carrying out certain tasks, which is associated with different degrees of academic success [78]. Therefore, this fact may explain the relationship obtained between EI and the reading-comprehension metacognitive-strategies variable. Several studies have specifically identified that EI has a positive effect on reading comprehension in different languages [79,80]. However, the literature has not considered the effect of EI on the self-reporting of metacognitive reading-comprehension strategies or the first language. Therefore, the results obtained are novel, and encourage the development of research that can provide more knowledge about this relationship.

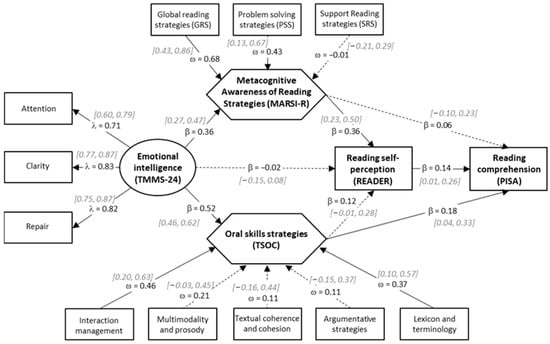

Another noteworthy result is the different effect of the reading-comprehension-strategies variable on self-perception of reading success (READER variable) and reading comprehension performance (PISA variable). As we have seen, self-knowledge of reading strategies has a significant positive effect on reading self-perception, as evidenced by several authors (e.g., [45,46]). However, this effect was not observed when reading comprehension performance was analysed. This may be explained by the fact that, while reading self-concept refers to beliefs, perceptions and evaluations that students have about their own skills, competences and worth in the school context, academic reading achievement refers to the level of knowledge demonstrated in the area or subject, taking into account age and academic level [81]. Thus, if the self-reported knowledge of reading strategies is considered to have the same self-reported nature as reading self-perception, it is justifiable that the relationships between self-reported strategies have a greater effect on reading self-perception than on performance. However, our results showed a low–moderate significant correlation between READER and PISA (r = 0.22; see Table 5). This linear relationship between both variables is consistent with Pajares and Johnson [82]. We re-analysed the data, including the direct effect READER → PISA, and respecifying the direct and indirect effects of the PLS-SEM model (see Figure A1 in the Appendix B, for illustrative purposes). The relationship between self-perception as readers and reading performance, although statistically significant, is attenuated (β = 0.14), since part of the PISA variability is explained by the effect of oral communication strategies (β = 0.18). This model can be interpreted in the same way as the model proposed in Figure 2 (i.e., the values and the significance level of the parameters in both models are very similar). The same can be said if we re-specify the model, including the direct effect PISA → READER. Again, the relationship between self-perception as readers and reading performance is attenuated (β = 0.12), but, in this case, the reading-comprehension-strategies variable (MARSI-R) has a significant effect on the outcome, instead of the oral communication strategies (TSOC). Therefore, with the information available, it seems that both READER and PISA variables have low shared variance in the presence of other variables, not affecting the interpretation of the model proposed in this study, in Figure 2.

It can be highlighted that one of the possible differences between self-reporting measures and performance seems to be related to the effect of EI [83]. As seen in this paper, EI has a rather strong indirect effect on the performance of reading-comprehension tasks, which is compatible with the results of some papers that identified relationships between EI and academic success [76]. However, some authors, such as Villavicencio and Bernardo [84], have also observed that self-efficacy was more highly correlated with performance in the absence of negative emotions. Therefore, perhaps different EI scores may have affected the effect that MARSI-R (which is still a measure of self-efficacy) has on PISA performance. Thus, we propose the need for further studies to identify the interaction effect that EI may have on the relationship between self-reporting measures and actual performance.

In any case, EI is not the only relevant intermediate variable in the relationship between self-reported strategies and performance. In line with Bandura, Loecher et al. or Lee and Jonson-Reid [42,85,86], comprehension success is also mediated by aspects such as motivation or task persistence, among others.

Technical Considerations and Limitations

This work applied PLS-SEM, a recommended analysis technique for applying Confirmatory Composite Analysis [69,87]. PLS-SEM (or composite-based SEM) models are more flexible for analysing models that combine reflective and formative measures, than SEM models. In SEM, it is possible to analyse formative constructs in combination with reflective constructs. This statistical technique is characterised by imposing strong restrictions on the models evaluated, which can result in models with identification problems, which are difficult to justify in theoretical terms [4]. In this regard, Brown [66] gives some examples, such as setting the disturbance of composite variables to zero or specifying unidirectional paths between endogenous constructs. PLS-SEM does not have these identification problems. Moreover, compared to SEM, PLS-SEM is useful when the analysis is concerned with testing a theoretical framework from a prediction perspective, and when the structural model is complex (i.e., includes many constructs, indicators and/or relationships, avoiding a lack of power), as is the case in this study.

A critical difference between SEM and PLS-SEM is that, in the first approximation, researchers have widely used goodness-of-fit measures to evaluate models such as chi-square (χ2) or standard root-mean-square residual (SRMR) [66]. Some fit measures have been studied in PLS-SEM approximation, such as SRMR, root-mean-square residual covariance (RMStheta), or the exact fit test. However, the development of these measures is limited, so more research is needed [4]. On the other hand, the notion of fit is not fully transferable to PLS-SEM, since the objective in SEM is to minimize the differences between covariance matrices (fit indices are based on the difference between the observed and estimated covariance matrices), while the objective in PLS-SEM is to maximize the explained variance. In any case, we consider that the difficulty in assessing the fit of the PLS-SEM model proposed in this work, beyond its predictive and explanatory power (i.e., structure path and R2), is a limitation that must be pointed out (see Henseler et al. [74]), to delve into issues related to the validity of PLS-SEM models.

PLS-SEM should be understood as a complementary technique to classical SEM (CB-SEM) [88], being an ideal technique when the models to be tested are tentative and the objective is not so much to validate a consolidated theoretical model (the stated objective of SEM), but rather to focus on the researcher’s interest in prediction. It is also particularly useful when combining reflective and formative variables in the analysis of complex relationships. The flexibility of PLS-SEM in these scenarios, common in educational psychology, allows the researcher to know in a relatively simple way how the different predictive variables implemented contribute in terms of explained variance, as well as their direct and indirect relationships with the criteria of interest, constituting an essential source for elaboration and theoretical development.

This study has not considered the convergent validity (i.e., redundancy analysis) of the formative measures. For this, the study design must include the collection of data on some variable that serves to reflect in a similar way what is intended to be collected, through the formative measures evaluated. In our view, it is not easy to define quantitative measures that can be used to analyse the convergent validity of the MARSI-R, and especially the TSOC. It would be preferable to obtain some kind of qualitative assessment by teachers of students’ reading and speaking skills. On the other hand, to evaluate the structural model, Hair et al. [4] recommend applying PLS-predict to analyse the model’s out-of-sample predictive power. The use of PLS-predict consists in estimating the model on a subsample and assessing its predictive power on a different subsample. In this study, the total sample, although having sufficient statistical power to apply PLS-SEM, is not optimal for partitioning. Questions related to the convergent validity of the formative measures and the predictive power of the model should be referred to further studies.

5. Conclusions

This study was carried out using a PLS-SEM approach, which incorporates the reflective and formative nature of the different variables, and allows us to clarify the effect of EI on the perception of reading comprehension, oral strategies and skills, as well as reading performance and self-perception. In this study, we have confirmed that EI has a positive effect on oral and reading strategies, which in turn predict academic performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.O. and J.M.A.; methodology, D.O. and J.M.A.; software, D.O.; validation, D.O.; formal analysis, D.O.; investigation, D.O. and J.M.A.; resources, J.M.A.; data curation, D.O.; writing—original draft preparation, D.O., B.C., M.G., V.J. and J.M.A.; writing—review and editing, D.O., B.C., M.G., V.J. and J.M.A.; visualization, B.C.; supervision, J.M.A.; project administration, M.G. and J.M.A.; funding acquisition, M.G. and J.M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (Spain) under grants PID2019-105177GB-C21, PID2019-105177GB-C22, PID2022-136905OB-C21 and PID2022-136905OB-C22 by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033. And the APC was funded by the grant number PID2022-136905OB-C22.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of University of Barcelona (protocol code IRB00003099 and 21st December 2020) and Deontological Committee of Faculty of Psychology, Complutense University of Madrid (2020/21-007, 29th October 2020) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Estimated weights and loadings of the formative items.

Table A1.

Estimated weights and loadings of the formative items.

| Items | Weights | Loadings | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimation | 2.5% CI | 97.5% CI | Estimation | 2.5% CI | 97.5% CI | |

| TSOC | ||||||

| IM1 → interaction management | 0.306 | 0.060 | 0.530 | 0.669 | 0.466 | 0.821 |

| IM2 → interaction management | 0.438 | 0.196 | 0.651 | 0.751 | 0.567 | 0.877 |

| IM3 → interaction management | 0.561 | 0.343 | 0.750 | 0.832 | 0.687 | 0.930 |

| MP1 → multimodality and prosody | 0.247 | −0.027 | 0.491 | 0.590 | 0.343 | 0.770 |

| MP2 → multimodality and prosody | 0.300 | 0.075 | 0.510 | 0.614 | 0.408 | 0.765 |

| MP3 → multimodality and prosody | 0.369 | 0.119 | 0.586 | 0.696 | 0.493 | 0.835 |

| MP4 → multimodality and prosody | 0.511 | 0.252 | 0.736 | 0.808 | 0.621 | 0.923 |

| TCC1 → textual coherence and cohesion | 0.330 | 0.058 | 0.579 | 0.738 | 0.538 | 0.858 |

| TCC2 → textual coherence and cohesion | 0.114 | −0.153 | 0.397 | 0.613 | 0.385 | 0.777 |

| TCC3 → textual coherence and cohesion | 0.086 | −0.187 | 0.319 | 0.599 | 0.383 | 0.744 |

| TCC4 → textual coherence and cohesion | 0.349 | 0.042 | 0.630 | 0.841 | 0.671 | 0.922 |

| TCC5 → textual coherence and cohesion | 0.216 | −0.062 | 0.459 | 0.757 | 0.581 | 0.859 |

| TCC6 → textual coherence and cohesion | 0.249 | 0.016 | 0.485 | 0.718 | 0.537 | 0.836 |

| AS1 → argumentative strategies | 0.498 | 0.201 | 0.752 | 0.890 | 0.742 | 0.958 |

| AS2 → argumentative strategies | 0.491 | 0.183 | 0.735 | 0.880 | 0.736 | 0.948 |

| AS3 → argumentative strategies | 0.006 | −0.262 | 0.275 | 0.537 | 0.297 | 0.719 |

| AS4 → argumentative strategies | 0.107 | −0.149 | 0.357 | 0.542 | 0.308 | 0.719 |

| AS5 → argumentative strategies | 0.116 | −0.153 | 0.376 | 0.540 | 0.307 | 0.725 |

| LT1 → lexicon and terminology | 0.015 | −0.261 | 0.297 | 0.546 | 0.309 | 0.724 |

| LT2 → lexicon and terminology | 0.489 | 0.192 | 0.762 | 0.824 | 0.625 | 0.939 |

| LT3 → lexicon and terminology | 0.220 | −0.084 | 0.495 | 0.750 | 0.550 | 0.872 |

| LT4 → lexicon and terminology | 0.515 | 0.184 | 0.784 | 0.822 | 0.606 | 0.939 |

| MARSI-15 | ||||||

| GRS1 → global reading strategies | 0.633 | 0.404 | 0.830 | 0.868 | 0.711 | 0.942 |

| GRS2 → global reading strategies | 0.226 | −0.040 | 0.488 | 0.526 | 0.271 | 0.716 |

| GRS3 → global reading strategies | 0.181 | −0.086 | 0.423 | 0.657 | 0.450 | 0.790 |

| GRS4 → global reading strategies | −0.161 | −0.436 | 0.089 | 0.307 | 0.016 | 0.527 |

| GRS5 → global reading strategies | 0.384 | 0.124 | 0.612 | 0.682 | 0.433 | 0.831 |

| PSS1 → problem-solving strategies | 0.138 | −0.121 | 0.388 | 0.576 | 0.346 | 0.749 |

| PSS2 → problem-solving strategies | 0.378 | 0.114 | 0.606 | 0.774 | 0.586 | 0.887 |

| PSS3 → problem-solving strategies | 0.294 | 0.018 | 0.533 | 0.772 | 0.581 | 0.881 |

| PSS4 → problem-solving strategies | 0.414 | 0.144 | 0.676 | 0.796 | 0.594 | 0.916 |

| PSS5 → problem-solving strategies | 0.119 | −0.167 | 0.392 | 0.599 | 0.360 | 0.766 |

| SRS1 → support reading strategies | 0.004 | −0.341 | 0.340 | 0.623 | 0.381 | 0.777 |

| SRS2 → support reading strategies | −0.022 | −0.326 | 0.322 | 0.410 | 0.090 | 0.677 |

| SRS3 → support reading strategies | 0.523 | 0.202 | 0.732 | 0.785 | 0.559 | 0.892 |

| SRS4 → support reading strategies | 0.546 | 0.148 | 0.785 | 0.794 | 0.513 | 0.902 |

| SRS5 → support reading strategies | 0.251 | −0.150 | 0.661 | 0.643 | 0.311 | 0.868 |

Table A2.

Estimated weights and loadings of the reflective items.

Table A2.

Estimated weights and loadings of the reflective items.

| Items | Weights | Loadings | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimation | 2.5% CI | 97.5% CI | Estimation | 2.5% CI | 97.5% CI | |

| TMMS-24 | ||||||

| ATT 1 → Attention | 0.214 | 0.169 | 0.265 | 0.789 | 0.736 | 0.831 |

| ATT 2 → Attention | 0.205 | 0.164 | 0.254 | 0.796 | 0.749 | 0.836 |

| ATT 3 → Attention | 0.193 | 0.147 | 0.243 | 0.798 | 0.737 | 0.842 |

| ATT 4 → Attention | 0.241 | 0.195 | 0.291 | 0.765 | 0.696 | 0.819 |

| ATT 5 → Attention | 0.044 | −0.031 | 0.101 | 0.404 | 0.264 | 0.520 |

| ATT 6 → Attention | 0.098 | 0.042 | 0.143 | 0.680 | 0.585 | 0.752 |

| ATT 7 → Attention | 0.165 | 0.127 | 0.205 | 0.794 | 0.735 | 0.839 |

| ATT 8 → Attention | 0.138 | 0.096 | 0.173 | 0.824 | 0.760 | 0.869 |

| CLA1 → Clarity | 0.092 | 0.037 | 0.135 | 0.693 | 0.593 | 0.767 |

| CLA2 → Clarity | 0.152 | 0.111 | 0.192 | 0.757 | 0.686 | 0.814 |

| CLA3 → Clarity | 0.107 | 0.053 | 0.150 | 0.746 | 0.659 | 0.810 |

| CLA4 → Clarity | 0.182 | 0.141 | 0.223 | 0.762 | 0.699 | 0.811 |

| CLA5 → Clarity | 0.205 | 0.154 | 0.264 | 0.681 | 0.605 | 0.745 |

| CLA6 → Clarity | 0.151 | 0.108 | 0.193 | 0.782 | 0.707 | 0.839 |

| CLA7 → Clarity | 0.217 | 0.170 | 0.270 | 0.753 | 0.687 | 0.806 |

| CLA8 → Clarity | 0.225 | 0.188 | 0.271 | 0.806 | 0.757 | 0.845 |

| REP1 → Repair | 0.149 | 0.100 | 0.193 | 0.733 | 0.648 | 0.798 |

| REP2 → Repair | 0.194 | 0.150 | 0.239 | 0.789 | 0.726 | 0.840 |

| REP3 → Repair | 0.145 | 0.097 | 0.190 | 0.704 | 0.608 | 0.776 |

| REP4 → Repair | 0.184 | 0.146 | 0.220 | 0.826 | 0.771 | 0.868 |

| REP5 → Repair | 0.202 | 0.150 | 0.259 | 0.682 | 0.600 | 0.748 |

| REP6 → Repair | 0.227 | 0.177 | 0.276 | 0.728 | 0.656 | 0.785 |

| REP7 → Repair | 0.136 | 0.071 | 0.197 | 0.464 | 0.343 | 0.570 |

| REP8 → Repair | 0.196 | 0.136 | 0.259 | 0.603 | 0.498 | 0.687 |

Appendix B

Figure A1.

Alternative PLS-SEM model including the direct effect READER → PISA.

References

- Hanafiah, M.H. Formative vs. reflective measurement model: Guidelines for structural equation modeling research. Int. J. Anal. Appl. 2020, 18, 876–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonetto, A. Formative and reflective models: State of the art. Electron. J. Appl. Stat. Anal. 2012, 5, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadler, M.; Sailer, M.; Fischer, F. Knowledge as a formative construct: A good alpha is not always better. New Ideas Psychol. 2021, 60, 100832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, T.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Berrocal, P.; Extremera, N.; Ramos, N. Validity and reliability of the Spanish modified version of the Trait Meta-Mood Scale. Psychol. Rep. 2004, 94, 751–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gràcia, M.; Alvarado, J.M.; Nieva, S. Assessment of Oral Skills in Adolescents. Children 2021, 8, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtari, K.; Dimitrov, D.M.; Reichard, C.A. Revising the Metacognitive Awareness of Reading Strategies Inventory (MARSI) and Testing for Factorial Invariance. Psychol. Learn. Teach. 2018, 8, 219–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). PISA 2018 Ítems Liberados. Ministerio de Educación y Formación Profesional 2019a. Available online: https://sede.educacion.gob.es/publiventa/descarga.action?f_codigo_agc=20232 (accessed on 28 May 2023).

- López Fernández, C. Relación de la Inteligencia Emocional con el Desempeño en los Estudiantes de Enfermería. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Cádiz, Cádiz, Spain, 2012. Available online: https://rodin.uca.es/handle/10498/14128 (accessed on 7 May 2023).

- Pérez, N.; Castejón, J. Relación entre la inteligencia emocional y el cociente intelectual con el rendimiento académico en estudiantes universitarios. REME 2006, 9, 1–27. Available online: http://reme.uji.es/articulos/numero22/article6/numero%2022%20article%206%20RELACIONS.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Barchard, K. Does Emotional Intelligence assist in the prediction of academic success? Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2003, 63, 840–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brackett, M.; Mayer, J. Convergent, discriminant and incremental validity of competing measures of emotional intelligence. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 29, 1147–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, L.; Kirby, S. Is Emotional Intelligence an Advantage? An Exploration of the Impact of Emotional and General Intelligence on Individual Performance. J. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 142, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asensio, J.M.; Acarín, N.; Romero, C. Emociones, desarrollo humano y relaciones educativas. In La Vida Emocional. Las Emociones y la Formación de la Identidad Humana; Asensio, J.M., Carrasco, J.G., Cubero, L.N., Larrosa, J., Eds.; Ariel: Barcelona, Spain, 2016; pp. 21–68. [Google Scholar]

- Damasio, A. En Búsqueda de Spinoza. Neurobiología de la Emoción y los Sentimientos; Crítica: Barcelona, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Salovey, P.; Mayer, J. Emotional Intelligence. Imagin. Cogn. Pers. 1990, 9, 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, H. Estructuras de la Mente: La Teoría de las Inteligencias Multiples; Fondo de Cultura Económica: Mexico City, Mexico, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, J.; Salovey, P. ¿Qué es Inteligencia Emocional? In Manual de Inteligencia Emocional; Mestre, J.M., Fernández-Berrocal, P., Eds.; Pirámide: Madrid, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Salovey, P.; Mayer, J.D.; Goldman, S.L.; Turvey, C.; Palfai, T.P. Emotional attention, clarity, and repair: Exploring emotional intelligence using the Trait Meta-Mood Scale. In Emotion, Disclosure, & Health; Pennebaker, J.W., Ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1995; pp. 125–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Berrocal, P.; Extremera, N. La Inteligencia Emocional y la educación de las emociones desde el Modelo de Mayer y Salovey. Rev. Interuniv. Form. Profr. 2005, 19, 63–93. [Google Scholar]

- Barna, J.; Brott, P. How important in personal/social development to academic achievement? The Elementary school counselor’s perspective. Prof. Sch. Couns. 2011, 11, 212–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buenrostro, A.E.; Valadez, M.D.; Soltero, R.; Nava, G.; Zambrano, R.; García, A. Inteligencia emocional y rendimiento académico en adolescentes. Rev. Educ. Desarro. 2012, 20, 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Olarte, P.; Palomera, R.; Brackett, M. Relating emotional intelligence to social competence and academic achievement in high school students. Psicothema 2006, 18, 118–123. [Google Scholar]

- Newsome, S.; Day, A.; Catano, V. Assessing the Predictive Validity of Emotional Intelligence. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2000, 29, 1005–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broc Cavero, M.A. Inteligencia emocional y rendimiento académico en alumnos de educación secundaria obligatoria. Rev. Española Orientación Psicopedag. 2019, 30, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastug, M. The structural relationship of reading attitude, reading comprehension and academic achievement. Int. J. Soc. Educ. Sci. 2014, 4, 931–946. [Google Scholar]

- Song, K.; Na, B.; Kwon, H.J. A comprehensive review of research on reading comprehension strategies of learners reading in English-as-an-additional language. Educ. Res. Rev. 2020, 29, 100308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, M. Okuma Motivasyonu, Akici Okuma Ve Okudugunu Anlamanin Besinci Sinif Ogrencilerinin Akademik Basarilarindaki Rolu [The role of the reading motivation, reading fluency and reading comprehension on turkish 5th graders’ academic achievement]. Turk. Stud. 2013, 8, 1461–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolley, G. Reading Comprehension; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). PISA 2018 Assessment and Analytical Framework; PISA, OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumert, J.; Demmrich, A. Test motivation in the assessment of student skills: The effects of incentives on motivation and performance. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2001, 16, 441–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, J.; Schiefele, U. Motivationale Grundlagen der Lesekompetenz. In Struktur, Entwicklung und Förderung von Lesekompetenz; Schiefele, U., Artelt, C., Schneider, W., Stanat, P., Eds.; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrell, P.L.; Eisterhold, J.C. Schema theory and ESL reading pedagogy. TESOL Q. 1983, 17, 553–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pressley, M.; Afflerbach, P. Verbal Protocols of Reading: The Nature of Constructively Responsive Reading; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Solé, I.; Mateos, M.; Miras, M.; Martín, E.; Castells, N.; Cuevas, I.; Gràcia, M. Lectura, escritura y adquisición de conocimientos en Educación Secundaria y Educación Universitaria. Infanc. Aprendiz. 2005, 28, 329–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, V.; Puente, A.; Alvarado, J.M.; Arrebillaga, L. Measuring metacognitive strategies using the reading awareness scale ESCOLA. Electron. J. Res. Educ. Psychol. 2009, 7, 779–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateos, M. Ayudar a comprender los textos en la educación secundaria: La enseñanza de estrategias de comprensión de textos. Aula Innov. Educ. 2009, 179, 52–55. [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie, J.T.; Wigfield, A.; Barbosa, P.; Perencevich, K.C.; Taboada, A.; Davis, M.H.; Scafiddi, N.T.; Tonks, S. Increasing Reading Comprehension and Engagement Through Concept-Oriented Reading Instruction. J. Educ. Psychol. 2004, 96, 403–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artelt, C.; Schiefele, U.; Schneider, W. Predictors of reading literacy. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2001, 16, 363–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtari, K.; Reichard, C.A. Assessing students’ metacognitive awareness of reading strategies. J. Educ. Psychol. 2002, 94, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondé, D.; Jiménez, V.; Alvarado, J.M.; Gràcia, M. Analysis of the Structural Validity of the Reduced Version of Metacognitive Awareness of Reading Strategies Inventory. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 894327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy. In Encyclopedia of Human Behavior; Ramachaudran, V.S., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1994; Volume 4, pp. 71–81. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, B.J. Self-efficacy: An essential motive to learn. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collie, R.J.; Martin, A.J.; Malmberg, L.E.; Hall, J.; Ginns, P. Academic buoyancy, student’s achievement, and the linking role of control: A cross-lagged analysis of high school students. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2015, 85, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naseri, M.; Zaferanieh, E. The Relationship between Reading Self-Efficacy Beliefs, Reading Strategy Use and Reading Comprehension Level of Iranian EFL Learners. World J. Educ. 2012, 2, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, C. An empirical study of reading self-efficacy and the use of reading strategies in the Chinese EFL context. Asian EFL J. 2010, 12, 144–162. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, J.W.; Tunmer, W.E. A longitudinal study of beginning reading achievement and reading self-concept. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 1997, 67, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, M.J.; Andrieessen, J.; Schward, B.B. Collaborative argumentation-based learning. In The Routledge International Handbook of Research on Dialogic Education; Mercer, N., Wegerif, R., Major, L., Eds.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2020; pp. 76–88. [Google Scholar]

- Littleton, K.; Mercer, N. Interthinking: Putting Talk to Work; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Perrenoud, P. Desarrollar la Práctica Reflexiva en el Oficio de Enseñar. Profesionalización y Razón Pedagógica, 3rd ed.; Graó: Pinheiros, Brazil, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment—Companion Volume; Council of Europe Publishing: Strasbourg, France, 2001; Available online: https://www.coe.int/lang-cefr (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Gràcia, M.; Galván-Bovaira, M.J.; Sánchez-Cano, M. Análisis de las líneas de investigación y actuación en la enseñanza y el aprendizaje del lenguaje oral en contexto escolar. Rev. Esp. Linguist. Apl. 2017, 30, 188–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camus Ferri M del, M.; Iglesias Martínez, M.J.; Lozano Cabezas, I. Un estudio cualitativo sobre la competencia didáctica comunicativa de los docentes en formación. Enseñanza Teach. Rev. Interuniv. Didáctica 2019, 37, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards-Groves, C.; Davidson, C. Metatalk for a dialogic turn in the first years of schooling. In The Routledge International Handbook of Research on Dialogic Education; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2020; pp. 125–138. [Google Scholar]

- Dewaele, J. Multilingualism and affordances: Variation in self-perceived communicative competence and communicative anxiety in French L1, L2, L3 and L4. Int. Rev. Appl. Linguist. Lang. Teach. 2010, 48, 105–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, S. An Evaluation of Oral Language: The Relationship between Listening, Speaking and Self-efficacy. J. Educ. Res. 2017, 5, 1457–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Croucher, S.M.; Kelly, S.; Rahmani, D.; Burkey, M.; Subanaliev, T.; Galy-Badenas, F.; Lando, A.L.; Chibita, M.; Nyiransabimana, V.; Turdubaeva, E.; et al. A multi-national validity analysis of the self-perceived communication competence scale. J. Int. Intercult. Commun. 2020, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LOMLOE. Ley Orgánica 3/2020, de 29 de Diciembre, Por la Que Se Modifica la Ley Orgánica 2/2006, de 3 de Mayo, de Educación. Boletín Oficial del Estado, 340, de 30 de Diciembre de 2020. 2020, pp. 122868–122953. Available online: https://www.boe.es/boe/dias/2020/12/30/pdfs/BOE-A-2020-17264.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Clarke, P.J.; Snowling, M.J.; Truelove, E.; Hulme, C. Ameliorating children’s reading-comprehension difficulties: A randomized controlled trial. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 21, 1106–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, L.; Kumschick, I.R.; Eid, M.; Klann-Delius, G. Relationship between language competence and emotional competence in middle childhood. Emotion 2012, 12, 503–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, P.M.; Armstrong, L.M.; Pemberton, C.K. The role of language in the development of emotion regulation. In Child Development at the Intersection of Emotion and Cognition; Calkins, S.D., Bell, M.A., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; pp. 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindquist, K.A.; MacCormack, J.K.; Shablack, H. The role of language in emotion: Predictions from psychological constructionism. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasquier, A.; Ponthieu, G.; Papon, L.; Bréjard, V.; Rezzi, N. Working on the identification and expression of emotions in primary schools for better oral production: An exploratory study of links between emotional and language skills. Education 3-13 2022, 50, 1107–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Schuberth, F. Confirmatory composite analysis. In Composite-Based Structural Equation Modeling: Analyzing Latent and Emergent Variables; Henseler, J., Ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 179–201. [Google Scholar]

- Schuberth, F.; Henseler, J.; Dijkstra, T.K. Confirmatory composite analysis. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, T. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research, 2nd ed; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ondé, D.; Alvarado, J.M.; Sastre, S.; Azañedo, C.M. Application of S-1 bifactor model to evaluate the structural validity of TMMS-24. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, J.; Salovey, P. What is emotional intelligence? In Emotional Development and Emotional Intelligence: Implications for Educators; Salovey, P., Sluyter, D., Eds.; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 3–31. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2022; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Ray, S.; Danks, N.P.; Calero Valdez, A. R Package Seminr: Domain-Specific Language for Building and Estimating Structural Equation Models Version 2.1.0 [Computer Software]. 2021. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/seminr/ (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Streukens, S.; Leroi-Werelds, S. Bootstrapping and PLS-SEM: A step-by-step guide to get more out of your bootstrapping results. Eur. Manag. J. 2016, 34, 618–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trizano-Hermosilla, I.; Alvarado, J.M. Best alternatives to Cronbach’s alpha reliability in realistic conditions: Congeneric and asymmetrical measurements. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morilla-García, C. The Role of Emotional Intelligence in Bilingual Education: A Study on the Improvement of the Oral Language Skill. Multidiscip. J. Educ. Res. 2017, 7, 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCann, C.; Jiang, Y.; Brown, L.E.R.; Double, K.S.; Bucich, M.; Minbashian, A. Emotional intelligence predicts academic performance: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2020, 146, 150–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, H.N.; DiGiacomo, M. The relationship of trait emotional intelligence with academic performance: A meta-analytic review. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2013, 28, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabrizi, A.R.; Esmaeili, L. The relationship between the emotional intelligence and reading comprehension of Iranian EFL impulsive vs. reflective students. Int. J. Engl. Linguist. 2016, 6, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ates, A. The Impact of the Emotional Intelligence of Learners of Turkish as a Foreign Language on Reading Comprehension Skills and Reading Anxiety. Univers. J. Educ. 2019, 7, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghabanchi, Z.; Rastegar, R.E. The correlation of IQ and emotional intelligence with reading comprehension. Reading 2014, 14, 135–144. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano, A.; Uzquiano, M.; Rioboo, A.; Paz, R.; Castro, F. Estrategias de aprendizaje, autoconcepto y rendimiento académico en la adolescencia. REIPE 2013, 21, 195–212. [Google Scholar]

- Pajares, F.; Johnson, M.J. Confidence and competence in writing: The role of self-efficacy, outcome expectancy, and apprehension. Res. Teach. Engl. 1994, 28, 313–331. [Google Scholar]

- Adeyemo, D.A. Moderating Influence of Emotional Intelligence on the Link Between Academic Self-efficacy and Achievement of University Students. Psychol. Dev. Soc. 2007, 19, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villavicencio, F.T.; Bernardo, A.B. Negative emotions moderate the relationship between self-efficacy and achievement of Filipino students. Psychol. Stud. 2013, 58, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locher, F.M.; Becker, S.; Schiefer, I.; Pfost, M. Mechanisms mediating the relation between reading self-concept and reading comprehension. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2021, 36, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.S.; Jonson-Reid, M. The role of self-efficacy in reading achievement of young children in urban schools. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 2016, 33, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legate, A.E.; Hair, J.F., Jr.; Chretien, J.L.; Risher, J.J. PLS-SEM: Prediction-oriented solutions for HRD researchers. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2023, 34, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).