Abstract

This study presents the results of an analysis of teaching practices within the Master’s Programme in Teacher Training and Development, a collaborative Master’s coordinated by the University of Salamanca (Spain) for the Ecuadorian Teacher’s professional development. The objective is to reflect upon and analyse the Practicum processes from the multicultural model based on cultural pluralism complemented with a socio-critical approach, paying special attention to the dimensions of cultural and educational diversity framed in cooperative processes. In addition to documentary analysis, two Delphi studies were conducted, one involving administrators of educational centres hosting student teachers, and the other involving personnel responsible for Practicum management. The findings emphasise the importance of cooperative and collaborative processes involving all professionals from both countries, for binational teaching practices to respond constructively to the educational challenges of cultural diversity arising from globalization. The evidence of the elements from the cultural pluralism model provides an excellent reference point for this. The educational challenges of diverse and multicultural societies require responses from a socio-critical approach that analyses reality from broad perspectives such as cultural pluralism that permeates educational interventions, including teaching practices. This is a multidimensional process that requires continuous communication and cooperation processes.

1. Introduction

The primary legislation governing higher education is Law 3/2003 of 28 March, on Universities in Castilla y León (BOCYL of 23 April 2003), and Law 12/2010 of 28 October, which amends Law 3/2003 of 28 March, on Universities in Castilla y León (BOCYL of 10 November 2010). These laws establish the framework for academic, territorial, financial, and coordination regulations for the Universities of Castilla y León, including the principle of “Specific cooperation with all Ibero-American Universities”. Globalisation in all areas, including education, both benefits and requires the overcoming of territorial barriers and enables teaching in bi-national contexts.

In this regard, the University of Salamanca introduced the Master’s Programme in Teacher Training and Development (referred to as MPTTD) seven years ago. This Master’s degree has some special characteristics as it is delivered in a blended learning format by faculty from the University of Salamanca (Spain) to Ecuadorian teachers who conduct their in-person practical training in their home country. Moreover, Ecuador operates under two distinct educational systems with different calendars, the Sierra-Amazon and Coast regimes. The Coastal regime includes all coastal cities and Galapagos, such as Gua-yaquil, Esmeraldas, Portoviejo, Manta, and Santo Domingo. This regime starts classes in May of each year and ends in February of the following year. The Sierra regime includes the entire inter-Andean region and the Amazon, i.e., cities such as Quito, Tulcán, Ambato, Riobamba, and Cuenca. In this case, the academic year runs from September to June of the following year. In addition to differences in the timetable, there are other factors that make these two regions different, such as their dialects or differences in population density (higher in the coastal areas than in the highlands). All these differences imply two major subcultures that are also reflected in the education system.

Practical teaching experiences are a key element that provide a privileged opportunity to bridge the gap between theoretical knowledge and the reality of the classroom. Since its inception, the MPTTD Practicum has followed a progressive sequence of reflection, awareness, time commitment, engagement, and student involvement in a wide range of school contexts and educational situations.

The objective of this Practicum is to immerse students in the specific context of teaching and learning. This entails transferring the knowledge, information, skills, and competences acquired during the programme into real teaching practice to improve the quality of training.

The Practicum is worth 12 European ECTS credits and is conducted over two months. This period of work experience varies between the Coastal and Highland regimes and requires a differentiated planning.

The organisation of the Practicum involves a team composed of Coordinators from the three specialisations in the Master’s Programme (Language and Literature, Biology, and Learning Difficulties), the Practicum Coordinator, academic tutors from the University of Salamanca, and on-site tutors (educators from the schools where the activity takes place). Co-tutors, an educational entity composed of Ecuadorian professionals (Sigue-E), facilitate communication and interaction between academic tutors, on-site tutors, and the Practicum Coordinator.

This context sets the stage for this work, which delves into somewhat unconventional curricular practices due to the wide range of stakeholders involved and the collaboration between Spain and Ecuador for an intercultural performance that has managed to convert the difficulties of coordination and management between two countries with important sociocultural and educational differences between them, converting cultural diversity into an added value.

These unique characteristics can offer guidelines, tools, and suggestions for other international teacher cooperation initiatives. Based on these premises, this study delves deeper into cooperative teaching practices through the experience and evolution of the practices within this Master’s programme since 2015, analysing qualitatively the information gathered during seven years. The aim is to provide guidance on how to enhance teaching practices through cooperative and collaborative processes that address cultural diversity under the approach of multicultural pluralism or multiculturalism coupled with a socio-critical vision.

1.1. The Sociocultural Dimension of Education: The Socio-Critical Approach

Émile Durkheim stated that “common education is a function of the social state; for each society seeks to realise in its members, through education, an ideal specific to it” [1]. The role of education within a society is unquestionable, and it is considered a significant driver of development.

According to Bourdieu [2], the social space or organisation of society is grounded in cultural capital, which is the cultural heritage of that social space. Thus, society is organised around specific values that explain its structure. Consequently, the social space becomes a symbolic space that, when transformed into a kind of language, shapes the perspectives, priorities, ideologies, and interests of the components of each social group. In this way, the distribution of cultural capital allows the construction of a social space, and the educational institution, by promoting particular ways of understanding the world, aids in reproducing and maintaining it over time and history. This is only possible through the transmission of concepts from person to person, a communicative process through which each society and culture’s unique perspectives on the world are assimilated.

Education serves as a platform for the transmission and reproduction of various social relationships, but it is also a space where forms of reaction and opposition are generated, stemming from questions about society. This aligns with the idea that education should not only produce professionals but also compassionate, conscious, and critical citizens who not only reproduce the established social system but also contribute to its improvement with a transformative spirit [3].

Human capital results from a complex process of appropriation in which individuals are introduced into the prevailing culture. This concept ties in with the aspiration to seek more reflective and critical educational practices that raise awareness of the social and cultural roles played by educators and learners [4]. Consequently, teacher training cannot be a mere review of didactic formulas or specific discipline training; it must be the space that welcomes the teacher’s concern for transcending the place where, through reflection and analytical skills, they can clarify their position regarding educational issues and their role in the social dynamic.

These premises amplify the complexity of managing and implementing teaching practices between two countries with similarities but also significant cultural and educational differences.

Institutions of higher education must strive for integral human development, aiming to prevent, alleviate, and improve situations caused by marginalisation and social exclusion. These situations affect various groups who, due to the deficiencies in their environment, are forced to confront daily risks arising from neglect, maladjustment, exclusion, drug addiction, violence, social conflict, and delinquency. The United Nations advocates international cooperation in support of teacher training, particularly to assist the most vulnerable groups [5]. Training and capacity-building for interculturality is a priority for both the Ecuadorian [6] and Spanish [7] education systems.

Multicultural coexistence is a current reality that requires a preventative approach to education, preparing immigrants and host citizens for a new situation, fostering adaptation processes based on respect and mutual enrichment. Globalising processes generate significant migratory flows not only of economically disadvantaged individuals but also of professionals, including teachers who practice their profession outside their country of origin. From this perspective, universities and schools must propose common programmes that encompass all aspects that will shape the emergence of an intercultural vision of education, considering aspects such as ethnocentrism [8] or xenocentrism.

1.2. The Multicultural Model as a Frame

The cultural pluralism approach has been applied to the analysis of acculturation processes through networks [9], religious inclusion [10], and even cultural integration processes [11]. This paper considers this approach to improve the quality of educational practices implemented in two countries with important socio-educational and cultural differences: Spain and Ecuador.

Intercultural education is a necessity in changing societies, and educational processes must assume a central role in the processes of social change and reorganization [12].

In this global context of multicultural realities, different educational models emerge (assimilationist, segregationist, compensatory, and cultural pluralism). In this paper, we will start from cultural pluralism through the multicultural model in direct connection with Banks’ holistic model. Both models consider cultural diversity as a positive element that enriches educational processes based on spaces for dialogue that allow cultural differences to be recognised based on equal rights.

The aim of this model is to train all students (from both majority and minority cultures) to adapt to and learn about social reality based on multicultural competence. It requires fluid communication and collaboration processes between cultures.

Banks [13] incorporates into this model a broad curriculum perspective that addresses global contexts by encouraging critical analysis and reflection on social reality by all the actors who make up the school scenario. The intercultural approach is integrated with the socio-critical approach mentioned in the previous section.

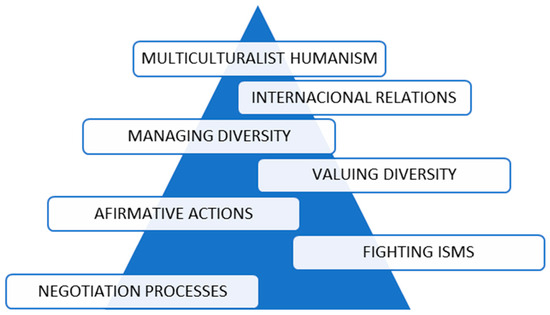

In order to analyse the curricular practices that are the focus of this research, we will rely on the elements which, according to Sabariego [12], make up the model of cultural pluralism and which are shown in the Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Pyramid of the elements of the model of cultural pluralism.

1.3. The Coordination of Teachers and Other Educational Stakeholders

There is widespread consensus regarding the significance of teacher collaboration and coordination in promoting innovation and improvement processes in schools [14,15]. The Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) studies, in which Spain has participated to date [16,17,18], emphasise teacher collaboration as one of the key elements in everyday teaching work. Similarly, some authors [19] highlight the positive association between teacher collaboration, professional development, and academic results.

With increasing intensity, researchers, educators, and educational institutions are advocating for greater coordination among all the involved stakeholders. Given the heterogeneity of educational contexts, the diversity of school types, cultural variations, and international collaborations, such as the one central to this study, the need for new structures and collaboration strategies becomes imperative. These must go beyond traditional views of school management and organisation [20].

Numerous studies have strived to demonstrate that teacher coordination opens up new opportunities for professional development supported by shared reflections on the intricacies of classroom practice. This facilitates and provides resources for learning within and from classroom practice [21,22].

However, cooperation should not be limited solely to teachers, as numerous educational stakeholders are involved in the teaching and learning processes [23]. More specifically, in curricular practices, there is a requirement for the institutionalisation of an agreement that regulates a student’s immersion in an educational institution with a very specific role. This process involves collaboration between the school’s directors and administrative personnel on one hand, and the counterpart personnel, which is the higher education institution that educates the students and its own institutional structure. In the case under consideration in this study, the organisational complexity is compounded by the physical distance and educational differences between Spain and Ecuador.

The role of school administrators in educational centres has been identified by various studies as crucial in creating collaborative working environments [24,25]. However, there are also studies that raise concerns about the effects of hierarchical power dynamics that limit the potential for teaching improvement and innovation [26,27].

Therefore, collaboration and cooperation processes with a focus on teachers are as necessary as they are complex in formative processes such as the one central to this study.

2. Materials and Methods

First, a documentary review has been conducted. For this purpose, 3 phases were followed: selection of all reports, guides, rubrics, verification reports, and other documents with relevant information; transformation based on a codification of the elements to be analysed; and analysis based on the objectives aimed at determining the evolution of the practicum process, the adjustments and changes made, and the overall volume of agreements and practicum students. This review has revealed that practicum agreements have been signed with 376 Ecuadorian schools, where 626 master’s students have completed their practicum over the course of 7 editions.

Two Delphi studies have been designed for application to a panel of experts, with experts defined as educational institution administrators in Ecuador who have hosted practicum students for at least two academic years in the MPTTD and personnel involved in the management of the Master’s Programme.

The selection of this research tool is conditioned by its utility in dealing with complex topics subject to some controversy. The Delphi technique is one of the most widely used in social research, ranging from identifying key themes to developing instruments and proposals for intervention or transformation. It possesses a certain predictive capacity for future processes and outcomes based on the systematic utilisation of intuitive judgment rendered by a group of experts.

The suitability of this technique in this study on teaching practices is linked to the complexity of the practicum system itself, situated between two countries with significant similarities and differences in their educational systems and sociocultural contexts.

Regarding the selection of educational institution administrators, the experts were chosen based on criteria such as experience, position, responsibility, geographical scope, and availability. The sample was balanced with respect to Ecuador’s educational systems, but it is slightly skewed in terms of gender perspective due to the greater difficulty in finding female directors given their lower numerical representation.

The specific profiles selected are outlined in the following Table 1, indicating the profile of each of the eight experts participating in the Delphi study.

Table 1.

Profiles of Delphi participants in educational institutions.

The application of this initial Delphi study consisted of two rounds of comprehensive questionnaires related to the research subject, to which the experts responded individually. Responses from the first questionnaire, which were sent in an online format, were analysed. Subsequently, a second questionnaire was issued, aiming to delve deeper into certain topics that lacked consensus and others considered crucial for the study, as identified by either the panel of experts or the research team.

The second Delphi was administered to three Practicum administrators, the two professors from the University of Salamanca who have overseen the coordination of the Practicum since its inception, and the professional responsible for academic and administrative affairs in Ecuador. On this occasion, the entire team directly involved in Practicum management was included, resulting in an exclusively female panel of experts (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Profiles of Delphi management participants.

In this case, due to the range and accuracy of the responses received in the first round, there was no need for a second round.

Based on the study’s objectives, the obtained results were systematised according to thematic clusters, supported by one or more verbatim (literal excerpts). Each verbatim is accompanied by an indication of the Delphi, specifying the corresponding profile and the questionnaire round in which the statement was made. For example, [P3-r1] refers to a contribution from profile number 3 in the first round of the Delphi conducted with educational institutions, and [G2] pertains to the second profile in the Delphi management round.

3. Results

3.1. Elements of the Cultural Pluralism Model

Initially, the contributions of the fieldwork are presented in relation to the model on which this work is based.

3.1.1. Negotiation Processes

The students are a fundamental pillar in the communication and negotiation processes. They are accompanied throughout the educational process by Ecuadorian tutors affiliated with Sigue-E, the entity responsible for implementing administrative and academic processes in Ecuador.

The Master’s students receive guidance and support during their internships from the team of tutors at SIGUE-E, clarifying their doubts or directing them to materials designed by the University.[G2]

They also form part of the Master’s Quality Committee and make suggestions for improvement. As a result of some of their requests, processes, and documents related to their internship period have been modified.

The Practicum Guide has been progressively modified with a spirit of constant improvement. It is available to all those involved in the process, providing clarity on roles, procedures, and tools.[P3r1]

Clear rubrics are in place for both the on-site tutors and the University tutors, which students are familiar with, ensuring a straightforward process.[P6r2]

3.1.2. Fighting Isms (Sexism and Racism)

Both the need for gender and race equality mainstreaming have been identified in the fieldwork.

I remember in one of the virtual sessions, the students mentioned that there was no gender pay gap in Ecuador. We searched for information about the country and in the next class, we explained what the gender pay gap was and what the percentage of the pay gap in Ecuador was. This is an example of different perceptions of certain realities. The students believed that since men and women at the same educational institution earned the same, there was no pay gap in the country.[G1]

I remember a meeting with a student who told me that she perceived racist expressions in her class with the indigenous children who were a minority, and I thought, the same thing that my Practicum students in Salamanca tell me when there are gypsy or immigrant children in the class.[p4r1]

3.1.3. Affirmative Actions

Various measures have been taken to enhance mutual understanding between Spain and Ecuador: training sessions in both countries, intensification of virtual Practicum sessions by its coordinator and specialty tutors, suggestions and strategies implemented by the Quality Commission.

The Master’s Programme’s Quality Commission, through its Internal Quality Assurance System (IQAS), has undertaken numerous actions since its inception to optimise the benefits of the richness and complementarity of Ecuador and Spain.[G3]

It can be deduced from the verbatim reports that in the framework of the Spain–Ecuador educational collaboration, the differences in context have been considered an element of mutual learning rather than a barrier. Differences in cultural capital and even in symbolic spaces have been an enrichment for teachers at the University of Salamanca.

I remember a meeting of the Quality Commission in which the Coordinator of Final Degree Projects commented that the tutors at the University were delighted to tutor projects with themes closely linked to the reality of Ecuador, such as the study of dialects for language teachers, the use of certain medicinal plants in the jungle for Biology teachers, for example.[G1]

3.1.4. Valuing Diversity

The context has been considered a relevant element in both Delphi studies. Regarding management, differences between the educational systems of Ecuador and Spain in higher education have not been deemed a significant factor. However, differences between both countries have been progressively identified and considered to enhance the quality of educational practices.

Undoubtedly, one element that has optimised both the processes and the results of a management that was not at all easy has been the fluid communication between the University of Salamanca in Spain and Sigue-E in Ecuador. We have been evaluating and revising annually the processes, documents, rubrics, etc. in order to reduce the gaps between countries and the differences that exist and to offer the best to our students.[G2]

This does not mean that cultural differences between the two countries have had to be progressively taken into account in order to improve the quality of educational practices.

Ecuador and Spain exhibit distinct educational and cultural realities, and each of these countries has its own internal differences. In Ecuador, there are even two educational regimes: Coast and Sierra, with different academic calendars that result in the Master’s degree having two Practicum periods.[G1]

We received suggestions from some educational institutions to increase communication between the tutors from the University of Salamanca and the on-site tutors. In recent editions, online virtual meetings have been scheduled and were evaluated very positively.[G2]

One of the notable differences is the significance for Ecuadorian teachers of completing this programme for their professional advancement.

For our student teachers, having this Master’s degree is crucial for career advancement within their institutions. Furthermore, it implies a significant salary improvement, which is why they make a great effort to complete it.[G2]

We have had several students here who were already teachers at the school. Finishing the Master’s Programme represents a substantial professional and economic progression for them.[P8r1]

The University of Salamanca enjoys a strong international reputation, and when we travel to Ecuador for evaluations or the graduation ceremony, we observe how important it is for students to hold a degree from this University.[G3]

3.1.5. Managing Diversity

The role of the Practicum coordinator, held by a professor at the University of Salamanca who has been involved with the Master’s programme since its inception, is highlighted as relevant.

Having a Practicum coordinator centralises the entire process, making it easier for all the pieces to fit together.[G3]

Various support and evaluation documents are also identified as playing an important role: evaluation rubrics, the Practicum Guide, and the Practicum report.

The assessment by the on-site Practicum tutor evaluates the classroom work and is handed over to the University teacher-tutor, who also has the Practicum report and monitoring process data to gain a comprehensive understanding of the learning process.[P4r1]

A descriptive letter of the Practicum is sent to the relevant authorities of the centres so they can have clarity on what the agreement entails.[G2]

3.1.6. International Relations

Given the unique nature of this Master’s degree at the University of Salamanca, primarily undertaken by students from Ecuador, specific coordination processes in the framework of bilateral relations through international exchange are required. Regarding the Practicum, these processes also involve teachers and administrators from Ecuadorian educational institutions where the practicums take place, in addition to the SIPPE (Service of Professional Insertion, Practicums, and Employment of the University of Salamanca).

All agreements with the recipient institutions for Master’s Practicum students must be signed through the SIPPE, in accordance with the University of Salamanca’s regulations.[G1]

More specifically, a series of actions have been implemented to intensify coordination and collaboration processes for the sake of effectiveness and efficiency. Some of the highlighted aspects include:

An introductory Practicum meeting for students, a procedure for signing agreements with the University and completing the educational training project, interviews with on-site tutors, as well as the inclusion of a project planning format and the collection of evidence of work.[G3]

Ecuadorian tutors provide reminders throughout the Practicum period, and instructional guides are developed to guide students.[G2]

Agreements are electronically signed from the University of Salamanca, eliminating the need to send physical documents.[G1]

3.1.7. Humanist Multiculturalism

All of the above elements converge with the idea of a global multicultural ideology that emphasises humanism. There is a significant consensus regarding the positive assessment of coordination and collaboration processes within the Master’s Programme among the numerous educational stakeholders involved.

We had a student teacher three years ago, and another one this year. We have noticed that coordination processes have improved with initial, final, and follow-up meetings between the University of Salamanca’s tutor and the one here. There are usually no issues, but this way, the tutors from Salamanca are informed about the progress, and it is more beneficial for the student.[P4r2]

The local teachers here enjoy conversing with the University professors. We discuss many things, not only about the student teacher, but also about education and the lack of family involvement, which we have noticed is common in both countries (…).[P2r1]

3.2. Past, Present, and Future

The seven cohorts of this Master’s Programme have allowed the refinement of processes through the identification of needs among the various stakeholders, commissions, and institutions involved in the MPTTD.

Several strengths have been identified through the robust planning and coordination processes mentioned, as well as the optimisation of the sociocultural diversity of both countries. Aspects such as innovation have been noted, where students implement new methodologies acquired during their training.

We have had two teachers from our school who studied the Master’s and completed their internships here. They have implemented two didactic proposals, one of which included questionnaires and research, contributing to improved innovation within the school.[P4r2]

Receiving interns at schools enriches us with strategies developed by the students and allows us to gather valuable information for further implementation.[P6r1]

At the same time, the Practicum is considered transcendental due to its repercussions, and ideas have been raised to increase its educational impact. It serves as a platform for reflection, proposing, and measuring innovative teaching and learning strategies that align with the context of each school.

This period of activities should sow the seeds of research-action in educators, encouraging them to continuously practice pedagogical models that enable them to address or meet needs. Finally, the successful results should also be disseminated, forming an interconnected teaching community capable of fostering new strategies for student development.[G2]

Finally, a series of future challenges have been identified, such as the process of students searching for practical experience or certain bureaucratic issues.

Educational institutions face limitations in assigning a Practicum tutor who can provide the necessary guidance and advice. This role is often assigned to another teacher as an additional task, leaving them with insufficient time to fulfill tutoring functions.[G2]

In the case of public schools in Ecuador, the school directors do not have the authority to sign cooperation agreements with universities. Hence, the procedures must be carried out with the districts or the Ministry of Education.[G2]

Negatively impacting the situation is the fact that students are responsible for initiating contact and the administrative process with institutions, and they are often rejected by school administrators.[G1]

4. Discussion

The research has highlighted that teacher collaboration is an essential condition for driving processes of innovation and improvement in educational institutions, as well as for student teachers. If to these factors we add international cooperation between two countries with cultural differences, it is essential to establish processes of communication and continuous improvement in order to optimise teaching from the cultural pluralism model, taking advantage of potentialities and minimising difficulties.

An important element emerging of the analysis has been the diversity between Ecuador and Spain in terms of their education systems, teaching practices, context, and culture. Within the Ecuadorian system, there are two education systems that respond to two geographically and culturally different areas. In Spain, educational transfers to the CCAA also consider the cultural diversity that emerges from different educational contexts.

Interculturality is inherent in many 21st-century schools [28], and it is a central aspect to consider in any educational planning. Furthermore, experiences such as this Master’s Programme demonstrate that with the appropriate processes of collaboration and cooperation among all education stakeholders, there is not only an enrichment of knowledge but also of attitudes and skills, ultimately enhancing the competences acquired by students.

Teacher collaboration alone does not guarantee the promotion of innovative processes; it can also contribute to perpetuating conservative and traditional teaching practices. The arrival of student teachers who have been trained in new methodologies and innovative processes represents a great opportunity to introduce with their practice processes new ideas, methods, and proposals aimed at improving not only academic results but also the processes of multicultural integration and inclusion needed in today’s society.

The findings emphasised the importance of cooperative and collaborative processes involving all professionals from both countries, including tutors (from educational centres, specialised tutors, and those from the University of Salamanca), the Practicum Coordinator, the Management and Administrative Coordinator in Ecuador, heads of educational institutions, and the Service for Professional Integration, Practicum, and Employment (SIPPE).

Effective communication and coordination have led to an improvement in these teaching practices in Ecuador, facilitated by the educational input from the University of Salamanca, with intercultural diversity playing a pivotal role in an approach geared towards the acquisition of competences.

In line with the propositions of other studies [29], in recent times the model of a university focussed almost exclusively on the teaching of curriculum content has been overcome. Now, the university has evolved into a place where the development and acquisition of competences empowering students for personal and professional development in a rapidly changing, diverse and multicultural environment are fundamental. The elements of the multicultural pluralism model can serve as a guideline for teaching practices between two culturally different countries, regions, or contexts because, as the results have shown, they encourage mechanisms and processes of educational improvement. Therefore, it is essential to maximise the potential of this process from a socio-critical framework based on the multicultural model for its socio-educational impact on both the schools and the teachers and prepares them for an inclusive teaching future. In this forward-looking perspective, cooperative and collaborative processes, as well as cultural diversity, have proven to be important elements. Finally, it is important to point out that there are many different models and theories on multicultural education which, as in this work, can be combined with other approaches such as the socio-critical one, always with the common objective of contributing to a constant enrichment between educational theory and practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.M.R. and B.M.R.; methodology, N.M.R.; validation, N.M.R. and B.M.R.; formal analysis, N.M.R. and B.M.R.; investigation, B.M.R.; resources, B.M.R.; data curation, N.M.R.; writing—original draft preparation, N.M.R. and B.M.R.; writing—review and editing, N.M.R. and B.M.R.; visualization, N.M.R.; supervision, N.M.R.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study did not require ethical approval (it was consulted with the committee).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. After consultation with the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Salamanca, the committee determined that the evaluation was not necessary, as none of the research questions could identify the participants, guaranteeing their anonymity. The research purposes were disclosed, and all final respondents consented to participate in the study (by a consent form at the beginning of the questionnaire), voluntarily and in accordance with the purposes of the research.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the reported results are available in Spanish. Any necessary information can be requested from the authors of this article at any time.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the University Master’s Degree in Teacher Training and Improvement at the University of Salamanca and Sigue-E Ecuador for their documentary support and participation in the development of this research, as well as the Ecuadorian schools and management staff who participated in the Delphi.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Durkheim, E. Educación y Pedagogía: Ensayos y Controversias; Editorial Losada: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Cuestiones de Sociología; Colección Fundamentos Nº 166; Ediciones Akal: Madrid, Spain, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz Saavedra, J.; Galdames Calderón, M. Educación para la Justicia Global: Temáticas, objetivos y criterios para una educación transformadora. Hum. Rev. Rev. Int. Humanidades 2022, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liz, D.L.D.; Álvarez, P.M.B.; León, M.A.N.; Alanya, S.M.R. La práctica pedagógica en un proceso de cambio. Cienc. Lat. Rev. Científica Multidiscip. 2022, 6, 4397–4409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. La Agenda 2030 y los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible: Una oportunidad para América Latina y el Caribe; United Nations: Santiago, Chile, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Panizo Toapanta, A. Migración e inclusión: Retos en el sistema educativo ecuatoriano. Rev. Andin. De Educ. 2019, 2, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montanuy, À.T.; Abeledo, I.C.; Lalana, P.L. Educación intercultural en España: Enfoques de los discursos y prácticas en Educación Primaria. Profr. Rev. Currículum Form. Profr. 2022, 26, 367–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang Yu, C.; Vendrell Pleixats, J.; Escrig, C.B.; Lalueza, J.L. Descentrar la mirada etnocéntrica: Una experiencia basada en los fondos de conocimiento. Athenea Digit. Rev. Pensam. Investig. Soc. 2023, 23, e3150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozer, S.; Kamran, M.A. Majority acculturation through globalization: The importance of life skills in navigating the cultural pluralism of globalization. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2023, 96, 101832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajibola, I.G. A Deconstruction of the Cross and the Crescent for Inclusive Religious Pluralism between Muslims and Christians in Nigeria. Religions 2023, 14, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, B.W. The Paradox of Pluralism: Municipal Integration Policy in Québec. Natl. Ethn. Politics 2023, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabariego, M. La Educación Intercultural Ante los Retos del Siglo XXI; Desclée de Brouwer: Bilbao, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Banks, J.A. An Introduction to Multicultural Education; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, P.; Pupik, C. Negotiating a common language and shared understanding about core practices: The case of discussion. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2019, 80, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellado, M.; Rincón Gallardo, S.; Aravena, O.; Villagra, C. Acompañamiento a redes de líderes escolares para su transformación en comunidades profesionales de aprendizaje. Perfiles Educ. 2020, 42, 52–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OCDE. TALIS 2013: Results: An International Perspective on Teaching and Learning; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- OCDE. TALIS 2018: Results: Teachers and School Leaders as Lifelong Learners; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Resultados de TALIS 2018: Nota Sobre el País—España; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ronfeldt, M.; Farmer, S.O.; McQueen, K.; Grissom, J.A. Teacher collaboration in instructional teams and student achievement. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2015, 52, 475–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orbegozo, E.F.M. Colaboración docente dentro del aula: Modelos, barreras y beneficios. In La organización Escolar. Repensando la Caja Negra para Salir de Ella; Fernández Enguita, M., Ed.; Anele-Rede: Madrid, Spain, 2020; pp. 83–96. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, D.L.; Schnellert, L. Collaborative inquiry in teacher professional development. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2012, 28, 1206–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäppinen, A.; Leclerc, M.; Tubin, D. Collaborativeness as the core of professional learning communities beyond culture and context: Evidence from Canada, Finland, and Israel. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 2015, 27, 315–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, P.C. Stumped by Student Needs: Factors in Developing Effective Teacher Collaboration. Electron. J. Incl. Educ. 2014, 3, 1–30. Available online: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/ejie/vol3/iss2/4 (accessed on 31 July 2023).

- Marchetti, B.; Porta, L. La articulación entre los niveles de definición de la política educativa en Argentina. La experiencia del plan de capacitación docente Escuelas de Innovación (2011–2015). Itiner. Educ. 2022, 16, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczesiul, S.; Huizenga, J. The burden of leadership: Exploring the principal’s role in teacher collaboration. Improv. Sch. 2014, 17, 176–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muijs, D.; Rumyantseva, N. Coopetition in education: Collaborating in a competitive environment. J. Educ. Change 2014, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galaz Ruiz, A.; Jiménez Vásquez, M.S.; Díaz Barriga, Á. Evaluación del desempeño docente en Chile y México: Antecedentes, convergencias y consecuencias de una política global de estandarización. Perfiles Educ. 2019, 41, 177–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izarra Vielma, D. La responsabilidad del docente entre el ser funcionario y el ejercicio ético de la profesión. Rev. Educ. 2019, 43, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, R.R.R. Convivencia intercultural: Un desafío democrático en la educación del siglo XXI. Rev. Dialogus 2022, 6, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).