Does Home or School Matter More? The Effect of Family and Institutional Socialization on Religiosity: The Case of Hungarian Youth

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Church Schools as Agents of Religious Socialization

3. The Context of the Study

4. Materials and Method

5. Results

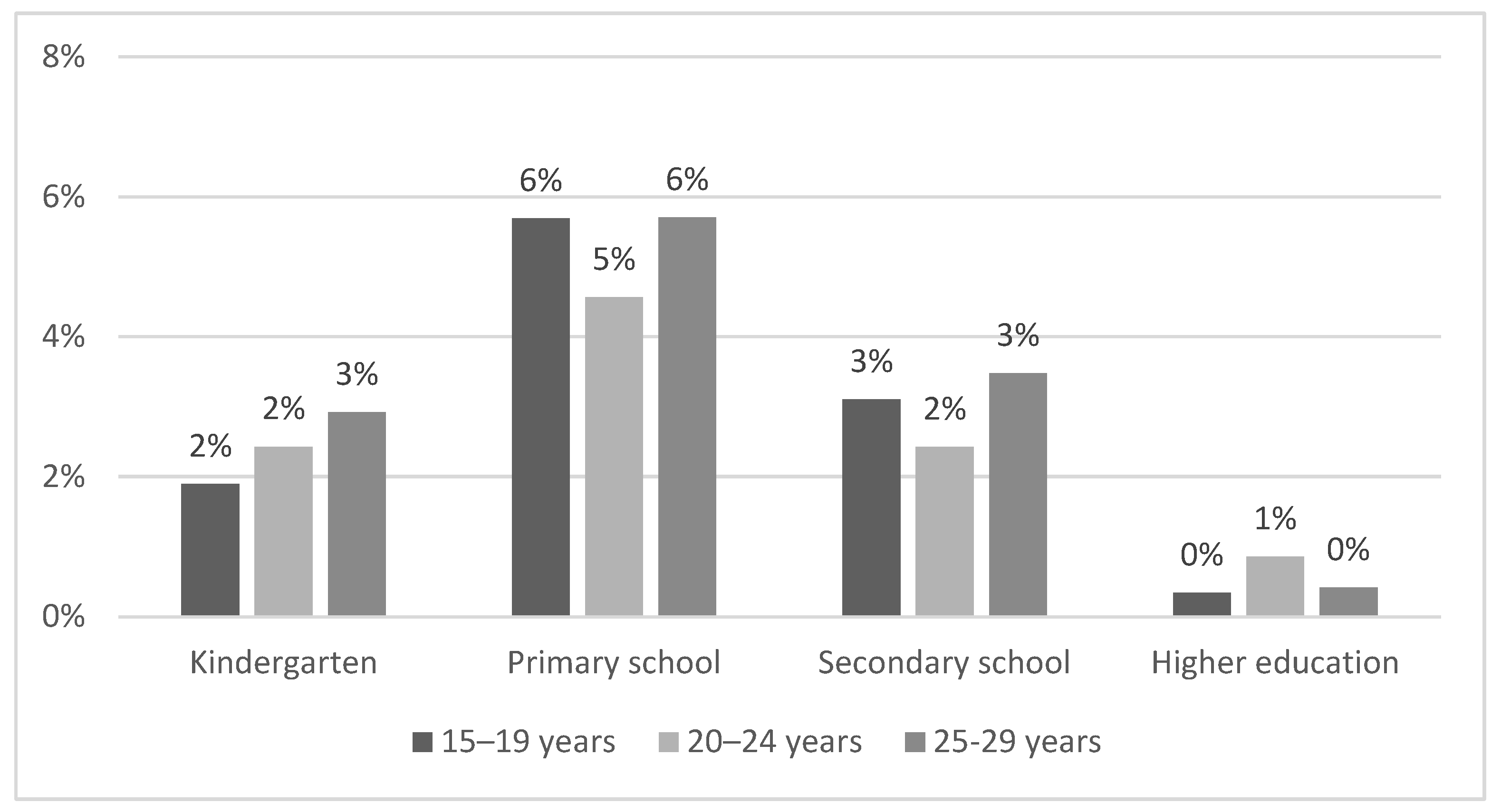

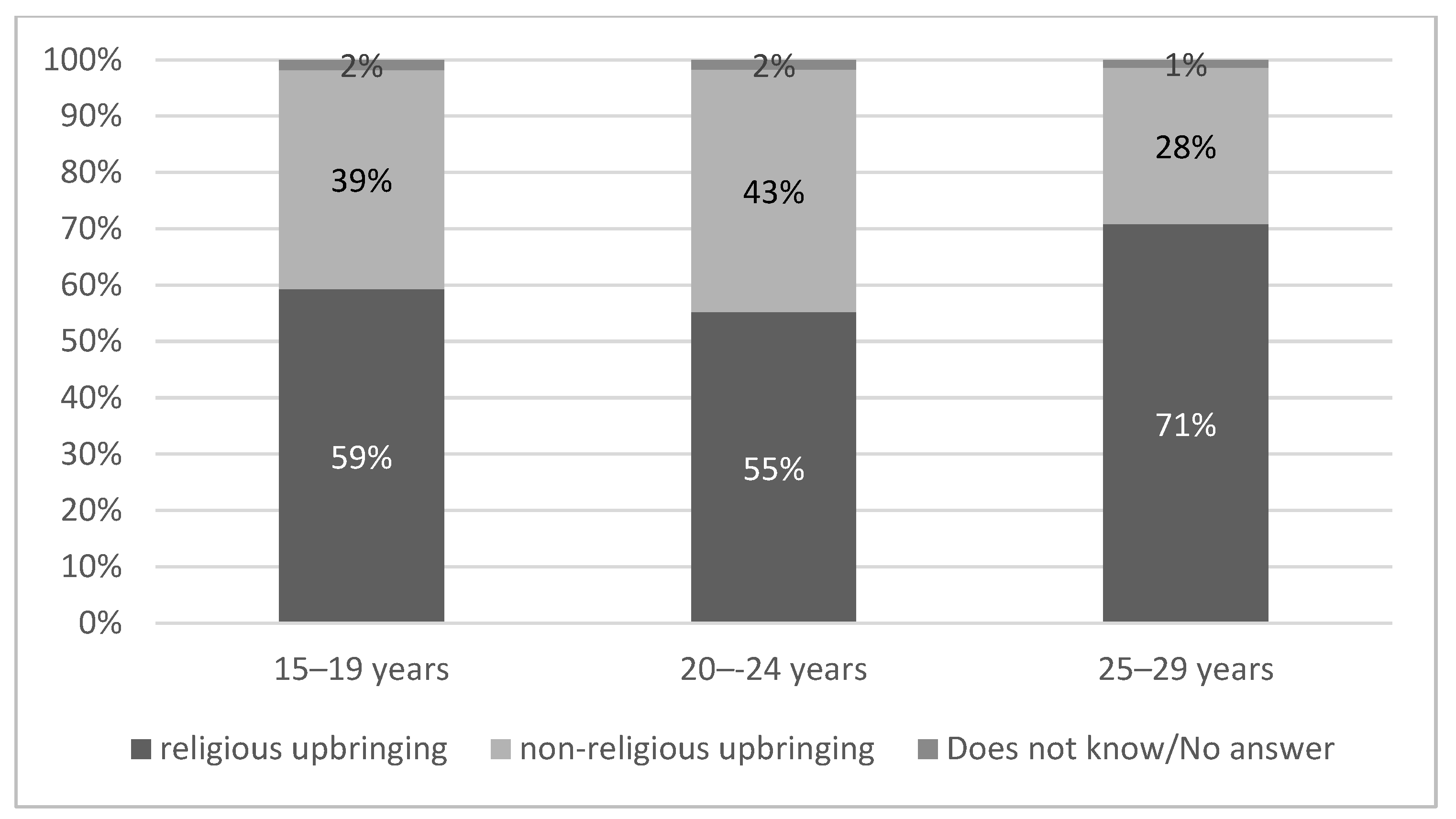

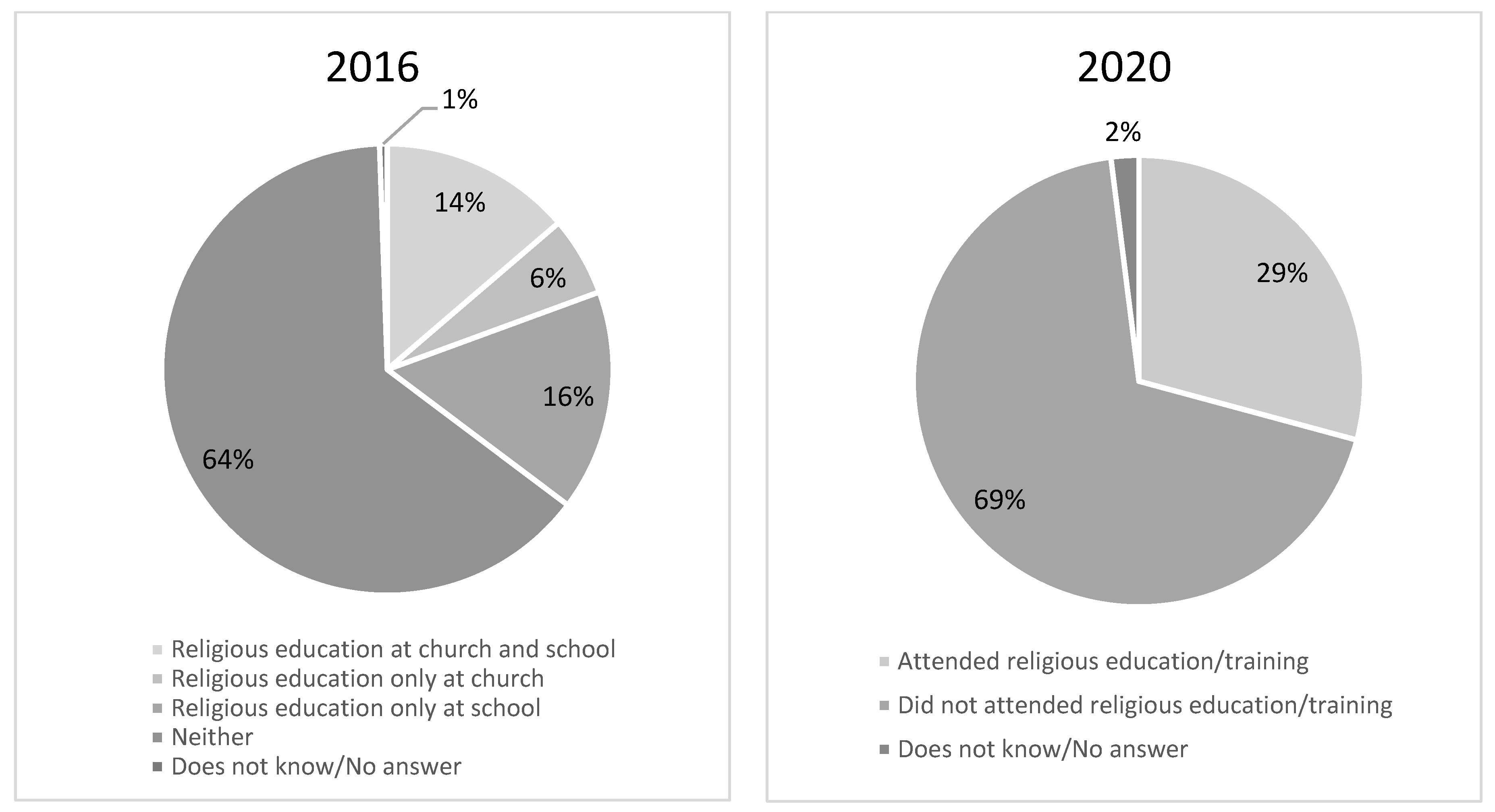

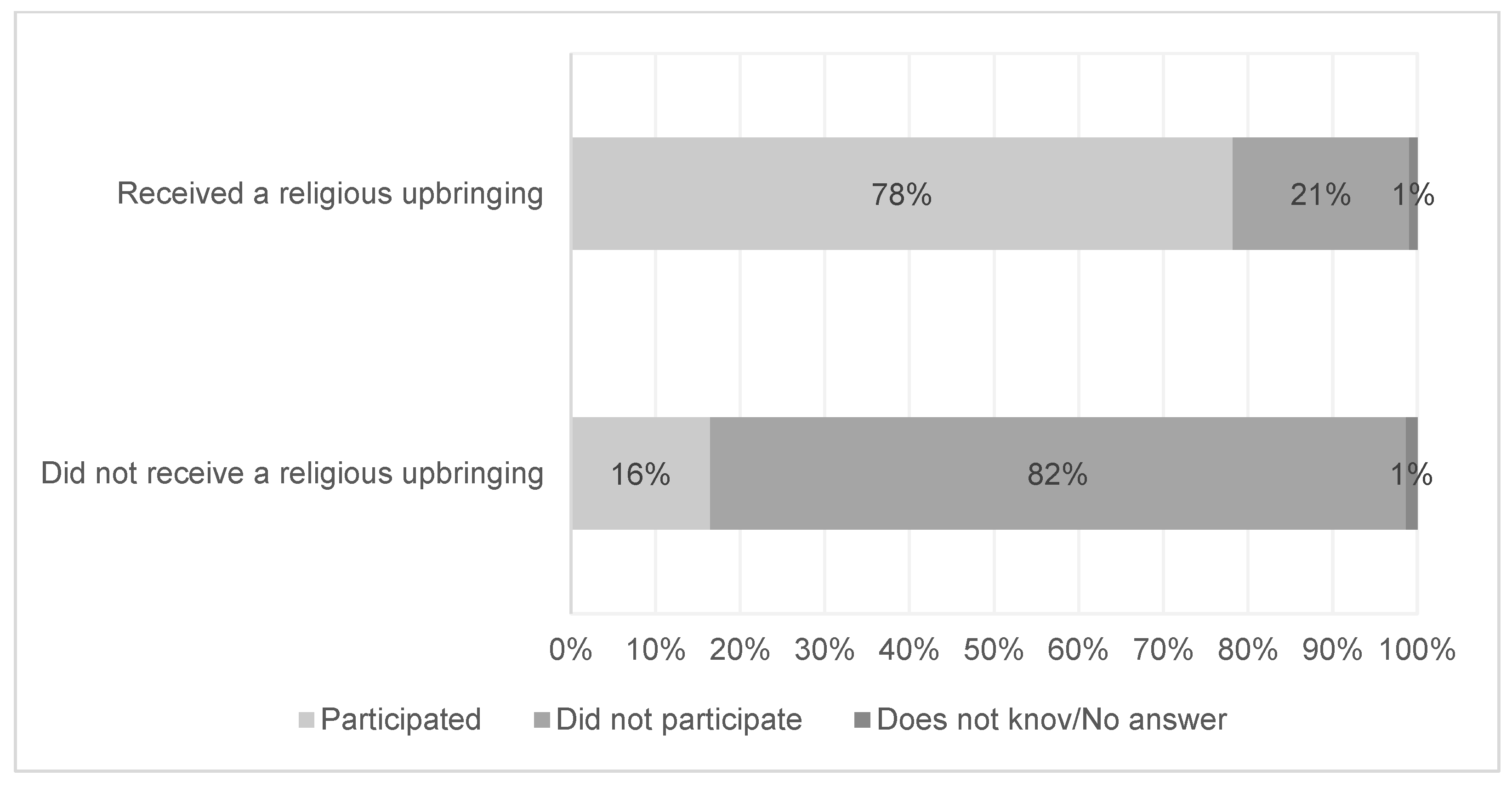

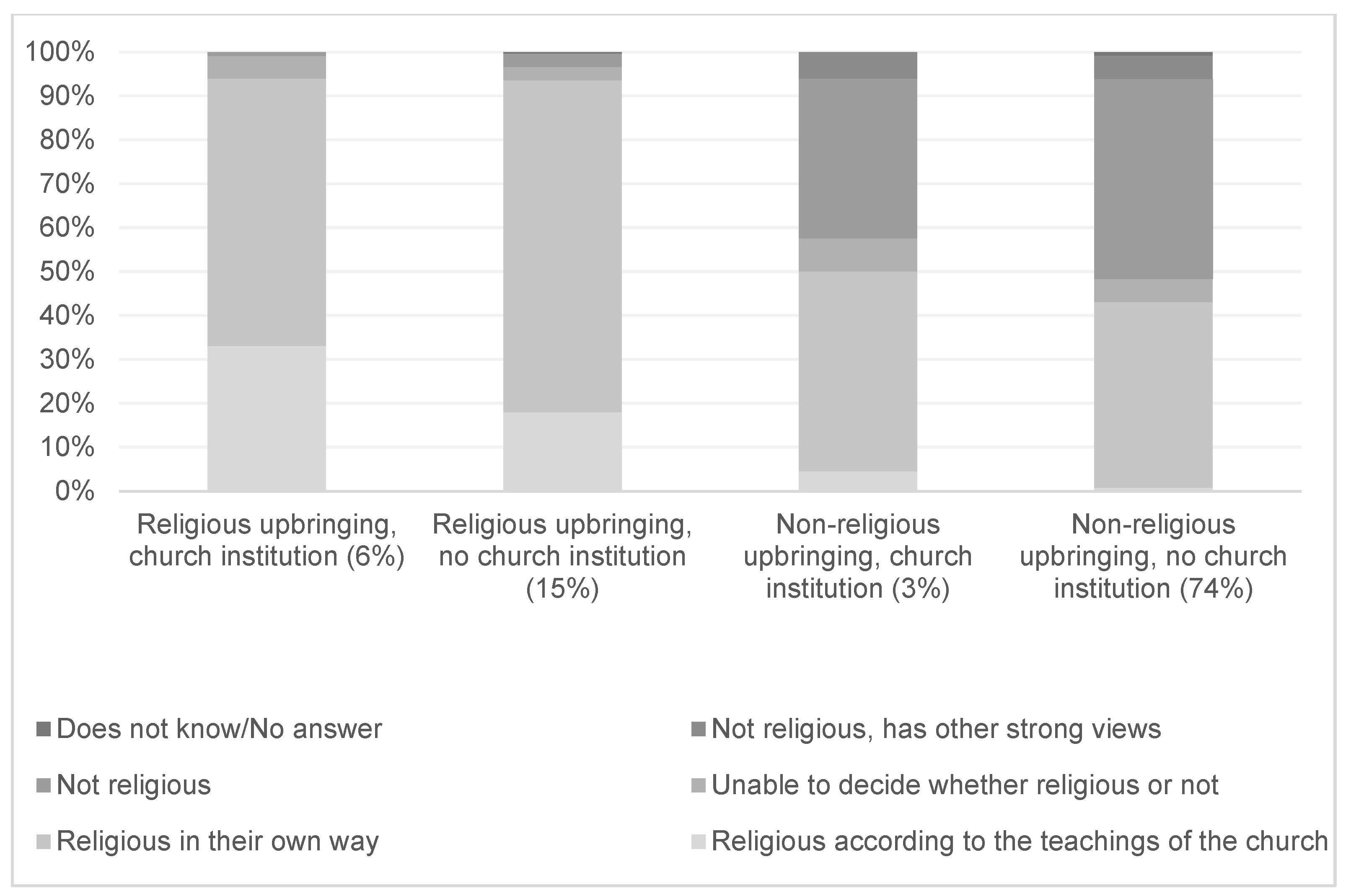

5.1. Descriptive Analysis of Religious Socialization

5.2. Agents of Religious Socialization and Their Effect on Religiosity

6. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Coleman, J.S.; Hoffer, T.; Kilgore, S. High School Achievement: Public, Catholic and Privat Schools Compared; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J.S.; Hoffer, T. Public and Private High Schools—The Impact of Communities; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Dronkers, J. The Existence of Parental Choice in the Netherlands. Educ. Policy 1995, 9, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, S.L.; Sorensen, A.B. Theory, Measurement, and Specification issues in Models of Network Effects on Learning. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1999, 64, 694–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dronkers, J.; Róbert, P. A különböző fenntartású iskolák hatékonysága. Educatio 2005, 14, 519–533. [Google Scholar]

- Pusztai, G. Community and social capital in Hungarian denominational schools today. Relig. Soc. Cent. East. Eur. 2005, 1, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Glanville, J.L.; Sikkink, D.; Hernández, E.I. Religious involvement and educational outcomes: The role of social capital and extracurricular participation. Sociol. Q. 2008, 49, 105–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikkink, D. Religious School Differences in School Climate and Academic Mission: A Descriptive Overview of School Organization and Student Outcomes. J. Sch. Choice 2012, 6, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Pelt, D.A.N.; Sikkink, D.; Pennings, R.; Seel, J. Private Religious Protestant and Catholic Schools in the United States and Canada: Introduction, Overview, and Policy Implications. J. Sch. Choice 2012, 6, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A.; Sikkink, D. A Longitudinal Analysis of Volunteerism Activities for Individuals Educated in Public and Private Schools. Youth Soc. 2020, 52, 1193–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, J.S. Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital. Am. J. Sociol. 1988, S95–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryk, A.; Schneider, B. Trust in Schools: A Core Resource for Improvement; Rusell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, J.W.; Dell, M.L. Stages of Faith from Infancy Through Adolescence. In The Handbook of Spiritual Development in Childhood and Adolescence; Roehlkepartain, E.C., King, P.E., Wagener, L., Benson, P.L., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006; pp. 34–45. [Google Scholar]

- De Hart, J. Impact of Religious Socialisation in the Family. J. Empir. Theol. 1990, 3, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherkat, D. Religious socialization: Sources of influence and influences of agency. In Handbook of The Sociology of Religion; Dillon, M., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003; pp. 151–163. [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney, A. Religion in Families, 1999–2009: A Relational Spirituality Framework. J. Marriage Fam. 2010, 72, 805–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeer, P. Religion and Family Life: An Overview of Current Research and Suggestions for Future Research. Religions 2014, 5, 402–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusztai, G.; Fényes, H. Religiosity as a Factor Supporting Parenting and Its Perceived Effectiveness in Hungarian School Children’s Families. Religions 2022, 13, 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desrosiers, A.; Kelley, B.S.; Miller, L. Parent and peer relationships and relational spirituality in adolescents and young adults. Psychol. Relig. Spiritual. 2011, 3, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, T.F.; White, J.M.; Perlman, D. Religious socialization: A test of the channeling hypothesis of parental influence on adolescent faith maturity. J. Adolesc. Res. 2003, 18, 169–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franken, L.; Vermeer, P. Deconfessionalising RE in pillarised education systems: A case study of Belgium and the Netherlands. Br. J. Relig. Educ. 2019, 41, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogero-García, J.; Andrés-Candelas, M. School choice and post hoc family preference in Spain: Do they match up? Educ. Policy Anal. Arch. 2020, 28, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leszczensky, L.; Flache, A.; Sauter, L. Does the share of religious ingroup members affect how important religion is to adolescents? Applying Optimal Distinctiveness Theory to four European countries. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2020, 46, 3703–3721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiner, P. Religious education in the European context. HERJ Hung. Educ. Res. J. 2013, 3, 4–14. [Google Scholar]

- Franken, L. Coping with diversity in Religious Education: An overview. J. Beliefs Values 2017, 38, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arold, B.W.; Woessmann, L.; Zierow, L. Can Schools Change Religious Attitudes? Evidence from German State Reforms of Compulsory Religious Education; WorkingPaper No. 22-508; Annenberg Institute for School Reform at Brown University: Providence, RI, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sjöborg, A. Religious education and intercultural understanding: Examining the role of religiosity for upper secondary students’ attitudes towards RE. Br. J. Relig. Educ. 2013, 35, 36–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltesova, V.; Pleva, M. The influence of religious education on the religiosity of Roma children in Slovakia. Relig. Educ. 2020, 115, 536–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodácsy-Simon, E. The Possible Role of Religions in Early Childhood Education and Care in the context of a post-communist heritage in Hungary. In The Routledge International Handbook of the Place of Religion in Early Childhood Education and Care; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2022; pp. 295–305. [Google Scholar]

- Galabova, L. Religious Socialisation of Children and Youth in Eastern Orthodox Christian Church as Educational and Pastoral Challenge of Sharing of Cultural Practices. Cent. Eur. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 2, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomka, M. Vallásosság Kelet-Közép-Európában. Tények és értelmezések. Szociológiai Szle. 2009, 19, 64–79. [Google Scholar]

- Gereben, F. Vallomások a vallásról. [Confessions about religion]. In Studia Religiosa; Máté-Tóth, A., Jahn, M., Eds.; Szeged, Bába és Társa: Szeged, Hungary, 1997; pp. 32–45. [Google Scholar]

- Davie, G. Praying Alone? Church-Going in Britain and Social Capital. J. Contemp. Relig. 2002, 17, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, A. Believing in Belonging: An Exploration of Young People’s Social Contexts and Constructions of Belief. Cult. Relig. 2009, 10, 263–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnoe, M.L.; Moore, K.A. Predictors of religiosity among youth aged 17–22: A longitudinal study of the National Survey of Children. J. Sci. Study Relig. 2002, 41, 613–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bano, M.; Ferra, E. Family versus school effect on individual religiosity: Evidence from Pakistan. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2018, 59, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uecker, J.E. Catholic schooling, Protestant schooling, and religious commitment in young adulthood. J. Sci. Study Relig. 2009, 48, 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sander, W. The Effects of Catholic Schools on Religiosity, Education, and Competition; The National Center for the Study of Privatization in Education: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Regnerus, M.D.; Smith, C.; Smith, B. Social Context in the Development of Adolescent Religiosity. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2004, 8, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agirdag, O.; Driessen, G.; Merry, M.S. The Catholic school advantage and common school effect examined: A comparison between Muslim immigrant and native pupils in Flanders. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 2017, 28, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardak, B.A.; Vecci, J. Catholic school effectiveness in Australia: A reassessment using selection on observed and unobserved variables. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2013, 37, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bauer, B.; Pillók, P.; Ruff, T.; Szabó, A.; Szanyi, F.E.; Székely, L. (Ezek a Mai Magyar Fiatalok! Magyar Ifjúság Kutatás 2016 Első Eredményei [These are Today’s Hungarian Youth! The First Results of Hungarian Youth Research 2016]; Új Nemzedék Központ Nonprofit Kft: Budapest, Hungary, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hámori, Á.; Rosta, G. Youth, Religion, Socialization. Changes in youth religiosity and its relationship to denominational education in Hungary. Hung. Educ. Res. J. 2013, 3, 46–60. [Google Scholar]

- Kisnémet, L.F. Iskola és vallásosság. Felekezeti iskolások az új évezred első évtizedében [School and religiosity. Religious students in the first decade of the new millennium]. Kapocs 2015, 14, 17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Pusztai, G. A Vallásosság Nevelésszociológiája. Kutatások Vallásos Nevelésről és Egyházi Oktatásról [Sociology of Religious Education: Research on Religious Education and Church-Run Schools]; Gondolat Kiadó: Budapest, Hungary, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rosta, G. Youth and religiosity in Hungary, 2000–2008. Anthropol. J. Eur. Cult. 2010, 19, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Földvári, M. Religiosity and values in Hungarian society. In Sociology of Religion in Hungary: Work in Progress; Tomka, M., Ed.; Pázmány Péter Katolikus Egyetem: Budapest, Hungary, 2004; pp. 25–42. [Google Scholar]

- Glenn, C.L. Does Catholic Distinctiveness Matter in Catholic Schools? Rev. Faith Int. Aff. 2019, 17, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacskai, K. Teachers of Reformed Schools in Hungary. Educ. Pract. Syst. Theory 2009, 4, 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Bacskai, K. School Effect in Different Sectors of Education. HERJ Hung. Educ. Res. J. 2018, 8, 131–135. [Google Scholar]

- Ter Avest, I.; Bertram-Troost, G.; Miedema, S. Religious education in a pillarized and postsecular age in the Netherlands. In Religious Education in a Plural, Secularised Society: A Paradigm Shift; Franken, L., Loobuyck, P., Eds.; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2011; pp. 85–98. [Google Scholar]

- Cain, T. School-university links for evidence-informed practice. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocsi, V.; Ceglédi, T. Is the glass ceiling inaccessible? The educational situation of Roma youth in Hungary. Balk. Forum 2021, 30, 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Székely, L. (Ed.) Magyar Fiatalok a Kárpát-Medencében. Magyar Ifjúság Kutatás 2016. [Hungarian Youth in the Carpathian Basin. Hungarian Youth Research 2016]; Kutatópont: Budapest, Hungary; Enigma 2001: Budapest, Hungary, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nagy, Á. Margón Kívül. Magyar Ifjúságkutatás 2016 [Outside of Margo. Hungarian Youth Research 2016]; Excenter Research Center: Budapest, Hungary, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pollack, D.; Rosta, G. Religion and Modernity. An International Comparison; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Glock, C.; Stark, R. Religion and Society in Tension; Rand McNally: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Tomka, M. The changing social role of religion in Eastern and Central Europe: Religion’s revival and its contradictions. Soc. Compass 1995, 42, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glock, C.Y. On the Study of Religious Commitment. In Religion’s Influence in Contemporary Society: Readings in the Sociology of Religion; Faulkner, J.E., Ed.; C. E. Merrill Publishing Company: Columbus, OH, USA, 1972; pp. 38–56. [Google Scholar]

- Cornwall, M.; Albrecht, S.L.; Cunningham, P.H.; Pitcher, B.L. The Dimensions of Religiosity: A Conceptual Model with an Empirical Test. Rev. Relig. Res. 1986, 27, 226–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Kindergarten | Primary School | Grammar School | Vocational Grammar School | Vocational Secondary School | Vocational School | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| proportion of church-run school sites | 8.2% | 15.2% | 29.7% | 17.2% | 15.0% | 8.0% |

| number of church-run school sites | 378 | 546 | 255 | 118 | 75 | 16 |

| proportion of children/students | 8.1% | 15.4% | 25.3% | 11.7% | 8.6% | 5.9% |

| number of children/students | 26,891 | 111,681 | 54,972 | 21,149 | 7837 | 414 |

| Dependent Variable: | Factor of Christian Beliefs | Factor of Non-Christian Beliefs |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (1 = male, 2 = female) | 0.050 * | 0.186 ** |

| Age | 0.029 | −0.006 |

| Place of residence (reference category: Budapest) | ||

| city with county rights | 0.035 | −0.092 ** |

| town | 0.009 | −0.048 |

| village | 0.014 | −0.150 ** |

| Mother’s education (reference category: max. primary school) | ||

| vocational school | −0.099 * | −0.070 |

| secondary school (matriculation exam) | −0.073 | −0.112 * |

| higher education | −0.057 | −0.131 ** |

| Father’s education (reference category: max. primary school) | ||

| vocational school | −0.059 | 0.004 |

| secondary school (matriculation exam) | −0.049 | 0.071 |

| higher education | 0.002 | 0.022 |

| Religious upbringing at home (1 = yes, 0 = no) | 0.349 ** | −0.092 ** |

| Church kindergarten, school, higher education (1 = yes, 0 = no) | 0.032 | 0.009 |

| Religious education (1 = yes, 0 = no) | 0.228 ** | 0.093 ** |

| Adjusted R2 total | 0.292 | 0.054 |

| Change in adjusted R2 when adding variables of religious socialization | 0.269 | 0.006 |

| N | 1751 | 1751 |

| Dependent Variable: | Religious in Accordance with the Teaching of the Church | Religious in Accordance with the Teaching of the Church or in His/Her Own Way | Frequency of Church Attendance |

|---|---|---|---|

| binary logistic regression | ordinal regression | ||

| Gender (reference category: male) | 1.121 | 1.110 | 1.462 ** |

| Age | 1.022 | 1.034 ** | 1.016 |

| Place of residence (reference category: Budapest) | |||

| city with county rights | 0.892 | 0.931 | 2.168 ** |

| town | 1.037 | 2.108 ** | 1.796 ** |

| village | 1.157 | 1.963 ** | 2.081 ** |

| Mother’s education (reference category: max. primary school) | |||

| vocational school | 0.543 | 1.316 | 0.725 |

| secondary school (matriculation exam) | 0.502 | 1.397 | 0.804 |

| higher education | 1.735 | 0.863 | 0.691 |

| Father’s education (reference category: max. primary school) | |||

| vocational school | 0.769 | 1.157 | 0.699 |

| secondary school (matriculation exam) | 0.559 | 1.087 | 0.793 |

| higher education | 1.140 | 2.449 ** | 1.228 |

| Religious upbringing at home (1 = yes, 0 = no) | 21.197 ** | 12.730 ** | 4.450 ** |

| Church-run kindergarten, school, higher education (1 = yes, 0 = no) | 1.977 * | 0.693 | 1.453 * |

| Religious education (1 = yes, 0 = no) | 1.800 | 2.732 ** | 2.780 ** |

| Nagelkerke’s pseudo R2 total | 0.398 | 0.308 | 0.281 |

| Change in Nagelkerke’s pseudo R2 when adding variables of religious socialization | 0.318 | 0.251 | 0.224 |

| N | 1848 | 1848 | 1838 |

| General-Post-Materialistic | Conservative | New Materialistic | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (1 = male, 2 = female) | 0.025 * | 0.042 ** | −0.047 ** |

| Age | 0.014 | −0.002 | −0.039 ** |

| Place of residence (reference category: Budapest) | |||

| city with county rights | −0.001 | −0.076 ** | 0.055 ** |

| town | −0.022 | −0.075 ** | −0.006 |

| village | 0.020 | −0.047 ** | −0.055 ** |

| Mother’s education (reference category: max. primary school) | |||

| vocational school | −0.002 | 0.079 ** | 0.001 |

| secondary school (matriculation exam) | 0.044 | 0.090 ** | −0.029 |

| higher education | 0.008 | 0.055 * | −0.067 ** |

| Father’s education (reference category: max. primary school) | |||

| vocational school | 0.083 ** | −0.032 | −0.091 ** |

| secondary school (matriculation exam) | 0.051 * | −0.015 | −0.034 |

| higher education | 0.080 ** | −0.008 | 0.004 |

| Has received a religious upbringing | −0.007 | 0.124 ** | 0.074 ** |

| Church kindergarten | 0.015 | 0.029 * | 0.023 |

| Church primary school | −0.042 ** | 0.014 | 0.016 |

| Church secondary school | 0.010 | −0.002 | −0.035 ** |

| Church higher education | −0.013 | 0.017 | 0.026 * |

| Religious education at school | 0.057 ** | −0.009 | −0.066 ** |

| Religious education at church | 0.122 ** | 0.007 | −0.072 ** |

| Other training related to religion | 0.012 | 0.005 | 0.007 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.030 | 0.028 | 0.028 |

| N | 7110 | 7110 | 7110 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pusztai, G.; Rosta, G. Does Home or School Matter More? The Effect of Family and Institutional Socialization on Religiosity: The Case of Hungarian Youth. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 1209. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13121209

Pusztai G, Rosta G. Does Home or School Matter More? The Effect of Family and Institutional Socialization on Religiosity: The Case of Hungarian Youth. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(12):1209. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13121209

Chicago/Turabian StylePusztai, Gabriella, and Gergely Rosta. 2023. "Does Home or School Matter More? The Effect of Family and Institutional Socialization on Religiosity: The Case of Hungarian Youth" Education Sciences 13, no. 12: 1209. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13121209

APA StylePusztai, G., & Rosta, G. (2023). Does Home or School Matter More? The Effect of Family and Institutional Socialization on Religiosity: The Case of Hungarian Youth. Education Sciences, 13(12), 1209. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13121209