Finding a Way: What Crisis Reveals about Teachers’ Emotional Wellbeing and Its Importance for Education

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Rolling Crisis and Expectations of Teachers

3. Emotionality and Teaching Performance

4. Teacher Emotional Rules

5. Context and Methods

5.1. Narrative

‘As a teacher I should love teaching. I must remain calm—neutral—at all times. Most importantly, anger and fear should not be displayed though discontentment may be expressed as frustration, sadness and worry, though these expressions should be limited as to not deviate into disloyalty toward my school or organisation. I do not feel discontented with students or parents because being in a classroom brings me happiness at all times. I do feel sadness at times, but this is when I see student suffering.’

‘Expressions of love towards students should be minimised, though I should be completely self-sacrificing for my students. Their emotions are more important than mine and their education is more important than my wellbeing. Of course, all of this would require me to be a robot, which I am not, so I will ultimately feel defeated, but I might never be aware of the degree in which I feel defeat, so I will never show it and keep keeping on.’

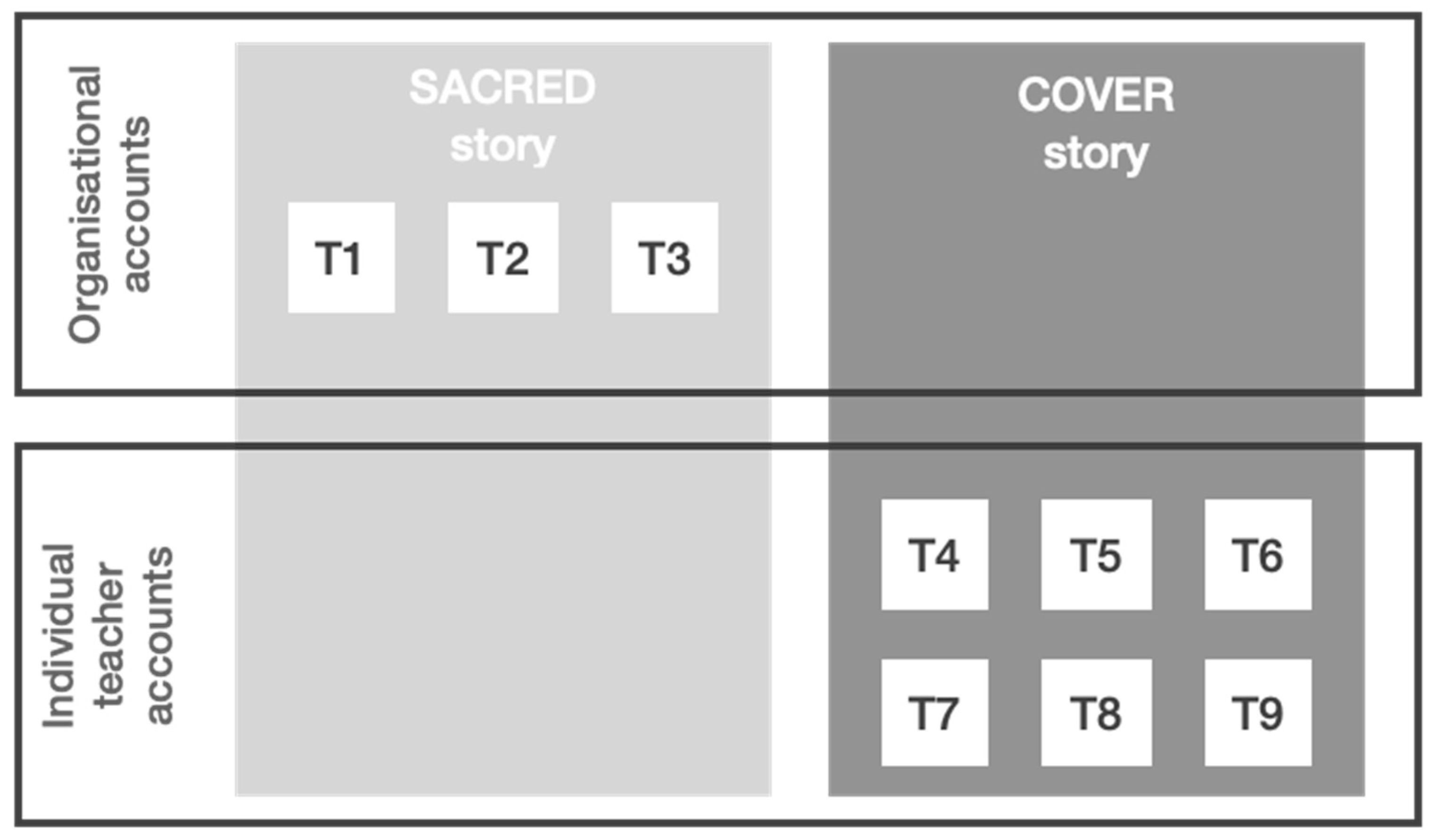

5.2. Methodology

‘I am tired of wearing masks. I am tired of not being able to go on field trips. I am tired of worrying that someone has COVID. I am just tired.’ @Twitter1 October 2020.

6. Findings and Discussion

6.1. Sacred Stories

‘Eye level’

‘Age-appropriate language’

‘Soft voice’

‘Yield to allow children to share thoughts or ask questions.’ (PBS Teachers, March 2020)

‘Confused, grumpy or happy? Every feeling is okay! Now is a stressful time for many—let your little ones know that it’s okay to experience emotions.’ (PBS Teachers, May 2020)

‘This new school year has brought new challenges and opportunities for all of us to overcome and adapt. It’s also come with a lot of different emotions. No matter what you are feeling right now—you are not alone. This #BackToSchool season, we are all in this together.’(DoE, September 2020)

‘Today at 7 p.m. ET: Join us for a webinar on grief and self-care during. Psychologist Thomas Demaria will suggest strategies to facilitate mourning as well as promote self-care, wellness, and resiliency.’ (NEA, October 2020)

6.1.1. Frustration, Worry, Sadness, and Anger Are Evoked by Student Interactions

6.1.2. Hope and Courage

‘Do you sometimes find yourself at a loss for words when explaining COVID-19 to your kids or students? Wisdom from Mister Rogers—“Look for the helpers”—is giving many of us hope right now.’ (PBS, May 2020)

‘If you need some help figuring out how to support students who may be experiencing trauma or unmet basic needs due to the pandemic, this is a great set of resources to start with. Social-Emotional Learning During COVID-19.’ (NEA, September 2020)

6.1.3. The Teacher Emotion Narrative in Relation to the Macro Crisis

6.2. Cover Stories

‘I was sad to learn our district will not be returning for the year. I did not know that saying goodbye at break would be saying goodbye for the year. I miss their questions, their light bulb moments, our jokes, and more. This is just sad.’ (@Twitter2, April 2020)

‘Day one virtual training. I spent 15 min getting the one not at all tech savvy teacher up to speed at the expense of all the other teachers who are trying to learn the next thing. Isn’t this exactly what the classroom is like? Too much time spent on that one student?’ (@Twitter3, August 2020)

‘Social distanced meetings, masks, and temperature checks. Looking forward to it!!!! (#sarcasm)’ (@Twitter4, July 2020)

‘To parents, If I provide before or after school support, don’t moan at me for “not fitting your child’s schedule”. Your child not attending remote classes or doing their work doesn’t fit my life—I’m not moaning to you...’ (@Twitter2, September 2020)

‘When I got into teaching, I knew the job was underappreciated, but I didn’t know that I would constantly be referred to as a “lazy babysitter” during a global pandemic while I spend my own money buying cleaning supplies to try to keep my students safe.’ (@Twitter5, August 2020)

- Frustration and anger over the uncertainty of the future and decisions being made about teachers’ work without teacher input.

- Worry over teacher, student, and broader community safety and over how teaching will be made possible in a lockdown world.

- Sadness about the loss of the typical teaching environment and an undermining of teacher safety and professionalism.

6.2.1. Teachers Should Not Feel or Display Fear

‘I am faced with some tricky decisions this year. Do I close the classroom door to keep my students safe from an active shooter or do I open it to improve air circulation?’ (@Twitter6, August 2020)

‘I can be scared for everyone’s health and still miss the classroom. I miss the interactions, collaboration, laughter, teaching, lightbulb moments, and more.’ (@Twitter2, July 2020)

6.2.2. Teachers Should Not Display Sadness to Students

‘Yesterday two students who hadn’t seen one another in several months ran together to hug. It brought tears to my eyes...’ (@Twitter4, May 2020)

6.2.3. Contentment Is Evoked by the Act of Teaching, by Students and Other Teachers; Happiness Is Evoked by the Act of Teaching and by Students

‘Had my first poor night’s sleep of the year due to teacher stress dreams. Is it actually mid-August?’ (@Twitter3, August 2020)

6.2.4. Defeat Is Inherent in Teaching but Must Not Be Shown

‘I wouldn’t trade my work and I love being back. Having said that… in the last two weeks I’ve cried about eight times. Teaching in 2020 is definitely a curve ball.’ (@Twitter2, September 2020)

6.2.5. Scepticism Is Permissible

‘Government buildings are closed due to the pandemic; however, politicians say teachers should go back to school.’ (@Twitter2, July 2020)

6.2.6. The Teacher Emotion Narrative in Relation to the Micro Crisis Reveals an Uncover Story

‘When teaching, I get frustrated, worry, sad and angry, but I do not only feel these things in relation to students. I do feel a lot of sadness about not being able to enjoy my students’ company while in lockdown—I miss our interactions. I also feel sad for students who are further disadvantaged due to inequities in the education system (for example, I am constantly reminded that students can only access online classrooms if they have adequate technology).’

‘I also feel sad for my teacher colleagues because they probably feel like I feel. Those of us who have family commitments find ourselves barely able to look after our own loved ones, terrified that this lethal virus could intervene to make that task impossible any day. Meanwhile our job is to teach and protect the children of so many other families.’

‘I grieve for the events that I looked forward to like field trips, sport days, music concerts and presentations. All these are cancelled now. I cry often. What I feel mostly is frustrated and worried. I am worried for the safety and wellbeing of my students, me and my family, and the state of the education system.’

‘Despite my best efforts, will my students learn what is expected? There is a load of professional learning out there, but it is not always appropriate, accessible, or timely—not to mention not having time to undertake the professional learning in the first place. Are we expecting too much? What is most frustrating is that teachers are not factored into the conversation, and I am sceptical about the choices made on my behalf by people who are not in classrooms living with the day-to-day challenges.’

‘Feelings of anger and fear are growing so that contentment in my work is becoming unreachable, and they are getting harder and harder to face each day. A sense of hope and courage is dissipating, and I am feeling the growing threat of defeat. How long can I keep going?’

6.3. Secret Stories

7. Final Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Clark, H.; Coll-Seck, A.M.; Banerjee, A.; Peterson, S.; Dalglish, S.L.; Ameratunga, S.; Balabanova, D.; Bhan, M.K.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Borrazzo, J.; et al. A future for the world’s children? A WHO–UNICEF–Lancet commission. Lancet Comm. 2020, 395, 605–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newnham, E.A.; Mergelsberg, E.L.P.; Chena, Y.; Kim, Y.; Gibbs, L.; Dzidic, P.L.; Ishida DaSilva, M.; Chang, E.Y.Y.; Shimomura, K.; Narita, Z.; et al. Long term mental health trajectories after disasters and pandemics: A multilingual systematic review of prevalence, risk and protective factors. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2022, 97, 102203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, L.S.; Kaufman, J.H.; Diliberti, M.K. Teaching and leading through a pandemic: Key findings from the American Educator Panels Spring 2020 COVID-19 Surveys. Rand Corp. 2020, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, L.E.; Asbury, K. ‘Like a rug had been pulled from under you’: The impact of COVID-19 on teachers in England during the first six weeks of the UK lockdown. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 90, 1062–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frenzel, A.C.; Daniels, L.; Burić, I. Teacher emotions in the classroom and their implications for students. Educ. Psychol. 2021, 56, 250–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auger, G.A.; Formentin, M.J. This Is depressing: The emotional labor of teaching during the pandemic spring 2020. J. Mass Commun. Educ. 2021, 76, 376–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, D.J.; Kim, L.E. Does teacher burnout affect students? A systematic review of its association with academic achievement and student-reported outcomes. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2021, 105, 101714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyanjom, J.; Naylor, D. Performing emotional labour while teaching online. Educ. Res. 2021, 63, 147–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soncini, A.; Politi, E.; Matteucci, M.C. Teachers navigating distance learning during COVID-19 without feeling emotionally exhausted: The protective role of self-efficacy. Sch. Psychol. 2021, 36, 494–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochschild, A.R. The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, J.H. The sociology of emotions: Basic theoretical arguments. Emot. Rev. 2009, 1, 340–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freud, S. The Unconscious; Phillips, A., Ed.; Frankland, G., Translator; Penguin Books: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Winnicott, D. The Maturational Processes and the Facilitating Environment: Studies in the Theory of Emotional Development; The Hogarth Press: London, UK, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Winnicott, D. The use of an object. Int. J. Psychoanal. 1969, 50, 711–716. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Statement on the Second Meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee Regarding the Outbreak of Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/30-01-2020-statement-on-the-second-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-outbreak-of-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov) (accessed on 25 September 2023).

- World Health Organization. Joint Statement by QU Dongyu, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus and Roberto Azevedo, Directors-General of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the World Health Organization (WHO) and the World Trade Organization (WTO). Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/30-03-2020-joint-statement-by-qu-dongyu-tedros-adhanom-ghebreyesus-and-roberto-azevedo-directors-general-of-the-food-and-agriculture-organization-of-the-united-nations-(fao)-the-world-health-organization-(who)-and-the-world-trade-organization-(wto) (accessed on 25 September 2023).

- Schatzki, T. Crises and adjustments in ongoing life. Osterr. Z. Soziol. 2016, 41 (Suppl. S1), 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. Sustainable Development Goals: 4 Quality Education. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/4_Why-It-Matters-2020.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2023).

- UNESCO. Education 2030 Incheon Declaration and Framework for Action for the Implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 4: Ensure Inclusive and Equitable Quality Education and Promote Lifelong Learning Opportunities for All. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000245656 (accessed on 25 September 2023).

- Cannon, S.R.; Davis, C.R.; Long, R. Using an emergency plan to combat teacher burnout following a natural hazard. Educ. Policy 2022, 37, 1603–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willse, C. State education agency governance, virtual learning, and student privacy: Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. Educ. Policy 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, L.E. Fear and loathing in neoliberalism: School leader responses to policy layers. J. Educ. Adm. Hist. 2015, 47, 140–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartell, T.; Cho, C.; Drake, C.; Petchauer, E.; Richmond, G. Teacher agency and resilience in the age of neoliberalism. J. Teach. Educ. 2019, 70, 302–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acton, R.; Glasgow, P. Teacher wellbeing in neoliberal contexts: A review of the literature. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 2015, 40, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesta, G.; Priestley, M.; Robinson, S. The role of beliefs in teacher agency. Teach. Teach. Theory Pract. 2015, 21, 624–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopman, J. Teacher emotional rules. In Professionalism and Teacher Education; Gutierrez, A., Fox, J., Alexander, C., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopman, J. Surviving Emotional Work for Teachers: Improving Wellbeing and Professional Learning through Reflexive Practice; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, K.; Jones, S. The everyday traumas of neoliberalism in women teachers’ bodies: Lived experiences of the teacher who is never good enough. Power Educ. 2021, 13, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. Refining the teacher emotion model: Evidence from a review of literature published between 1985 and 2019. Camb. J. Educ. 2021, 51, 327–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R.E.; Wheatley, K.F. Teachers’ emotions and teaching: A review of the literature and directions for future research. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2003, 15, 327–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, L.; Mansfield, C.; Dobozy, E. Teacher emotion research: Introducing a conceptual model to guide future research. Issues Educ. Res. 2015, 25, 415–441. [Google Scholar]

- Uitto, M.; Jokikokko, K.; Estola, E. Virtual special issue on teachers and emotions in Teaching and teacher education (TATE) in 1985–2014. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2015, 50, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šarić, M. Teachers’ emotions: A research review from a psychological perspective. J. Contemp. Educ. Stud. 2015, 66, 10–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Hall, N.; Taxer, J.L. Antecedents and consequences of teachers’ emotional labor: A systematic review and meta-analytic Investigation. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 31, 663–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bächler, R.; Salas, R. School memories of preservice teachers: An analysis of their role in the conceptions about the relationships between emotions and teaching/learning processes. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 690941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burić, I.; Kim, L.E.; Hodis, F. Emotional labor profiles among teachers: Associations with positive affective, motivational, and well-being factors. J. Educ. Psychol. 2021, 113, 1227–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karousiou, C.; Hajisoteriou, C.; Panayiotis, A. Teachers’ emotions in super-diverse school settings. Pedagog. Cult. Soc. 2021, 29, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burstein, R. Research Eclipsed: How Educators Are Reinventing Research-Informed Practice During the Pandemic. Available online: https://www.edsurge.com/research/reports/education-in-the-face-of-unprecedented-challenges (accessed on 25 September 2023).

- Clandinin, D.J.; Connelly, F.M. Teachers’ professional knowledge landscapes: Teacher stories—Stories of teachers—School stories—Stories of schools. Educ. Res. 1996, 25, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruner, J. Life as narrative. Soc. Res. 2004, 71, 691–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clandinin, D.J. Engaging in Narrative Inquiry; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Crites, S. The narrative quality of experience. J. Am. Acad. Relig. 1971, 39, 291–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stake, R.E. Multiple Case Study Analysis; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- PBS. About PBS. Available online: https://www.pbs.org/about/about-pbs/ (accessed on 25 September 2023).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, D. A worked example of Braun and Clarke’s approach to reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Quant. 2021, 56, 1391–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nvivo, version 12.7.0 [3873]; Computer Software; QSR International: Burlington, MA, USA, 2019.

- Twitter/X. Academic Research. Available online: https://developer.twitter.com/en/use-cases/do-research/academic-research (accessed on 25 September 2023).

- National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research 2023. Available online: https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/attachments/publications/National-Statement-Ethical-Conduct-Human-Research-2023.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hopman, J.; Clark, T. Finding a Way: What Crisis Reveals about Teachers’ Emotional Wellbeing and Its Importance for Education. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 1141. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13111141

Hopman J, Clark T. Finding a Way: What Crisis Reveals about Teachers’ Emotional Wellbeing and Its Importance for Education. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(11):1141. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13111141

Chicago/Turabian StyleHopman, Jean, and Tom Clark. 2023. "Finding a Way: What Crisis Reveals about Teachers’ Emotional Wellbeing and Its Importance for Education" Education Sciences 13, no. 11: 1141. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13111141

APA StyleHopman, J., & Clark, T. (2023). Finding a Way: What Crisis Reveals about Teachers’ Emotional Wellbeing and Its Importance for Education. Education Sciences, 13(11), 1141. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13111141