Abstract

This study aimed to ascertain if there was a significant impact on the acquisition of English language competence, motivation, attention, and emotions towards English as a Second Language (ESL) after the development of gamification based on the famous Among us game with primary education students aged 7–8 years (n = 24) from a state school in Ciudad Real (Castilla-La Mancha). An experimental method with a pretest–post-test design was considered, in which the control group followed a transmission instructional model, and the experimental group underwent an eight-session gamified experience using Information and Communication Technologies (ICT). Four ad hoc tests were designed and implemented to assess writing, reading, speaking, and listening skills, while various test adaptations were used to measure attention and motivation variables. The results show that gamification helped to improve the variables analyzed, showing significant enhancements in reading from the experimental group, as well as a more positive attitude towards the English subject, increased active participation, and fewer negative inclinations towards mistakes. The study suggests that incorporating gamification can have a positive impact on learning outcomes and may serve as a means of bridging linguistic inequalities and promoting equitable access to language learning opportunities. However, further research is necessary to explore the potential of gamification in this regard.

1. Introduction

Transmission instructional models have long been the most common teaching and learning process in schools. This model looks for students to obtain greater cognitive learning acquisition through teachers’ directions while they passively receive knowledge [1] through different problems [2], like the lack of cooperation among classmates or the difficulty of developing critical thinking, among other circumstances. Fortunately, this fact is changing, partially thanks to the new technologies that guide the learning process into a meaningful and constructivist interactive approach. As Sarramona defends, “one characteristic of the present and future times is the velocity and depth in which technical and social changes occur” [3] (p. 39). Thus, a change should be made to provide students with motivation for learning using active methodologies and approaches based on their personal interests.

The way that children interact and socialize with others and the world is through games [4]. Therefore, playing games helps students to challenge themselves while following rules in a motivational course of action [5]. This motivation partially appears since mistakes encountered during the game count as part of it, which implies that there is meaningful learning development [6]. However, traditional teaching methodologies tend to punish students for mistakes, increasing the stress and pressure on students. Hence, using games or game mechanisms in an educational context can provide a normalized view of experiencing errors. In this vein, gamification, which uses game mechanisms in non-ludic contexts, when used as a didactic methodology, allows attention and motivation to be enhanced, as well as developing positive feelings and providing students with performance improvements and meaningful learning [7,8]. Thus, research assumption 1 can be considered: gamification leads to performance improvements.

Continuing with this approach, the use of gamification in education “is a gradual developed tendency that enables students to enjoy while acquiring new knowledge, as well as, evaluating their learning process” [9] (p. 387). Therefore, gamification as a didactic methodology influences students’ participation by encouraging curiosity, strengthening the cognitive process, developing meaningful learning, improving attentional processes, maintaining students’ interest in the subject, obtaining immediate feedback and learning progression, and enhancing motivational attitudes [10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. Hence, research assumption 2, that gamification improves students’ attentional processes, as well as research assumption 3, that gamification enhances students’ interest towards the English subject, and research assumption 4, that gamification leads to motivational attitude enhancement, are borne in mind.

Specifically, in Spain, different projects that highlighted successful results in students’ performance using gamification [17,18,19,20]. In this regard, García, García, and Martín [17] carried out an investigation in a public school in Madrid using the gamification methodology to increase motivation and written production in students. This investigation used two groups of fifth grade primary education students (23 and 24 students) as the experimental group, and another group of students from the same grade (22 students) as the control group. A motivation questionnaire and a rubric evaluation were conducted to analyze the variables desired to be studied. The statistical analysis concluded with significant growth in the experimental group, enhancing motivation and written production. González [18] used the gamification methodology to study second grade students’ motivation in a school in Burgos. To do so, this author used a simple rubric filled up by 24 students from the class to determine what they learnt, enjoyed, and liked about the session. This investigation deduced that participation, interest, and academic results improved positively with the use of gamification. In light of the results considered in this project, research assumption 5 is considered: gamification improves students’ linguistic competence. Gargallo [19] used the gamification methodology in third grade kindergarten students (31 in total) to motivate them while learning the English language. To do so, Gargallo used a direct observation approach through an estimation scale and an interview with an action–investigation methodology. The investigation concluded that motivation and English use in class improved considerably, as well as attention focus and concentration on the tasks conducted. Cejudo, Losado, Pena, and Feltrero [20] used the gamification methodology to promote social and emotional learning in students. This intervention was aimed at young Dominican and Spanish people (145 and 187 adolescents, respectively) through a perception questionnaire. The results concluded that there were significant improvements in socioemotional competence in both groups of people.

With this scenario as a backdrop, the use of gamification in the classroom has become a powerful and effective alternative to traditional methodologies in order for students to undergo significant learning. In this sense, the aim of the present design study is to ascertain if there were significant impacts on the acquisition of English language competence, motivation, attention, and emotions towards ESL after the development of an eight-session gamified experience based on the famous Among us game. Thus, the research questions developed to pursue the main objective of the project, as well as to give responses to the research assumptions contemplated, are considered as follows:

- Are there any improvements in students’ performance from the pretest to the post-test after the gamification implementation?

- Can gamification improve students’ attention?

- Can gamification enhance students’ attitudes towards the English subject?

- Can gamification benefit students’ motivation?

- Can gamification positively impact students’ linguistic competence?

- Are there any significant differences between the control group’s results and the experimental group’s results within the post-test?

All things considered, in spite of the initial low levels of linguistic competence and motivation demonstrated by the sample considered, the implementation of gamification in the English primary school classroom had a markedly positive impact on learning outcomes when using the ICT. Specifically, it led to improvements in attention, participation, and motivation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodology

A manipulative and empirical study was conducted in the current project as an analysis of the causal relations among the different variables [21]. The independent variable was the utilization of gamification in class, while the dependent variables were the improvements in linguistic competence, motivation, and the attentional and emotional factors. An experimental research method with a pretest–post-test design applied to a group of study participants (n = 24) was effectuated. Thus, different types of tests related to the dependent variables were applied to the study group before and after the didactic intervention. Consequently, this group was divided into two small groups: the experimental group, in which the didactic intervention was employed, and the control group, which followed a transmission instructional model.

2.2. Participants and Context

The study was conducted in a state school in Ciudad Real (Castilla-La Mancha, Spain), whose sociological foundation is related to a medium–high socio-economic context, in which there are positive communicative relationships among students, teachers, and families according to the Educative Project of the school. The participants were 7–8-year-old students (n = 24; 50% males; 50% females) who were attending second grade of primary education. These students were divided into two groups according to systematic sampling: after choosing one student randomly for the experimental group, the other members of the very same group were considered every two positions in the school list until half of the original sample was reached. Then, the rest of the students from the school list belonged to the control group. Hence, the experimental group (n = 12; 50% males; 50% females) undertook the gamified experience, while the control group (n = 12; 50% males; 50% females) followed a traditional methodology. From the latter, one student was discarded within the control group analysis, since he was a native speaker; thus, the sample within the control group was n = 11 (45.5% males; 54.5% females).

2.3. Didactic Intervention Programme

Amonglish us is an eight-session didactic intervention programme which aims to improve English language competence, motivation, and attention towards this subject and how emotions are influenced. This didactic intervention is related to a specific unit from the Oxford Rooftops: Farm animals, due to the English teacher syllabus temporalization established at the time of its implementation. Amonglish us comes from the popular game Among us, as the same map is used, as well as some characters. The reason for this comes from the interest of the students from the sample towards this game. Additionally, the role of the impostor is changed slightly, as this specific student must randomly make mistakes in some sessions. Therefore, other students must work harder in order not to make mistakes to guess who the impostor is. Table 1 shows the functioning of the didactic intervention programme created.

Table 1.

Specific and detailed functioning of the didactic intervention program created, Amonglish us.

2.4. Instruments of Evaluation

A pretest and post-test were used to clarify the improvements of students in linguistic competence, attention, motivation, and emotions towards the English subject. The pretest was taken before the didactic intervention to evaluate students’ linguistic competence and their perceptions towards the English subject. After carrying out the didactic intervention, the post-test was taken by the experimental group and the control group to evaluate students’ linguistic competence and their perceptions towards gamification (experimental group) and the traditional methodology (control group). Thus, these tests were based on the adaptation of different standardized tests, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Pretest and post-test instruments.

In the present research, qualitative and quantitative techniques were used for the treatment of data. A total of 192 questionnaires (motivational assessment test and linguistic competence tests) were filled in by students, while a total of 96 questionnaires (emotions towards the subject interview and attention test) were filled in by the English teacher and me.

On the one hand, quantitative research conducted to evaluate the data obtained in the motivational assessment test, linguistic competence tests, and attention test was compiled in an Excel spreadsheet. Thus, these data obtained in the pretest and post-test could be compared using a descriptive statistics analysis. On the other hand, a semi-structured interview to analyze emotions towards the English subject was carried out using qualitative research to understand the influence of the didactic intervention on students’ emotions. Thus, Table 3 gathers the specific information to assess each test.

Table 3.

Assessment of each test used, which corresponds to the dependent variables to be analyzed.

3. Results

A data analysis was conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS). In this sense, the Shapiro–Wilk normality test was first applied to determine whether quantitative data were normally distributed for the following dependent variables: (1) linguistic competence, in terms of writing, reading, speaking, and listening; (2) attention; and (3) motivation. As considered in Table 4, all variables obtained p > 0.05, indicating a normal distribution; thus, parametric statistics needed to be applied.

Table 4.

Normality tests.

The student’s t-test was applied for independent samples (control group and the experimental group) within the pretest to ascertain the mean differences between groups. In this sense, the p-value was higher than 0.05 for all variables: linguistic competence (p = 0.407), motivation (p = 0.061), and attention (p = 0.444). Thus, there were no significant mean differences, indicating that both groups possessed the same levels of linguistic competence, motivation, and attention before the didactic intervention application. The student’s t-test was also applied within the post-test to observe the possible mean differences between the control group and the experimental group after the implementation of the didactic intervention. In this sense, the p-value was higher than 0.05 for motivation (p = 0.288) and attention (p = 0.281). However, the p-value was below 0.05 within the linguistic competence variable (p = 0.045). Hence, no significant mean differences were observed for the motivation and attention variables, while significant mean differences were considered for the linguistic competence variable within the post-test, in which the experimental group obtained better mean results than the control group, as observed in Table 5.

Table 5.

Group statistics within the post-test.

In this vein, the following sections describe a specific overview of the variables considered, along with their corresponding graphs.

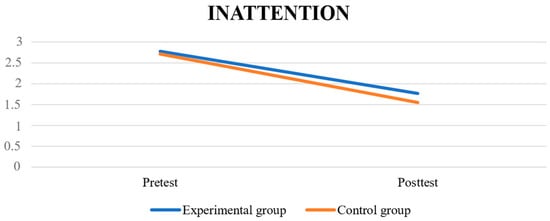

3.1. Attention Test

Regarding students’ attention, the results indicate that both groups’ inattention slightly lessened, noting a clear improvement in the comparison of the pretest and post-test (see Figure 1). Although there was no significant change between the experimental group and the control group (p > 0.05), the results show that the control group’s inattention decreased slightly more than the experimental group’s. However, the Paired Samples test shows how both groups improved considerably from the pretest to the post-test. The control group and experimental group means were significantly different from the pretest to the post-test (p < 0.001 for both of them, while t = −5.560 and t = −4.849, respectively). Thus, gamification and the traditional methodology improved students’ attention significatively.

Figure 1.

Attention test results for the pretest and post-test.

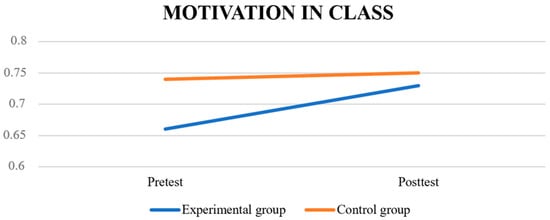

3.2. Motivational Assessment Test

Although no significant mean differences exist between the experimental group and the control group (p > 0.05), the Paired Samples test signals how the experimental group’s motivation significantly increased (p = 0.007, t = −2.927) from the pretest to the post-test thanks to gamification. However, even though the control group’s motivation also grew from the pretest to the post-test, its improvement was not significant (p = 0.148, t = −1.102), as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Motivational assessment test results from the pretest and post-test.

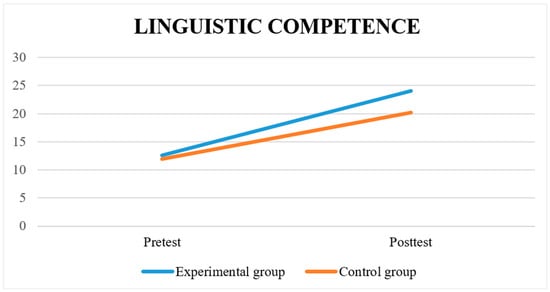

3.3. Linguistic Competence

Regarding the linguistic competence differentiation between both groups, it can be said that the experimental group’s mean was significantly different than the control group’s (p = 0.045, thus, p < 0.05) within the post-test due to gamification, as observed in Table 5 statistically and in Figure 3 graphically.

Figure 3.

Linguistic competence test results for the pretest and post-test.

When disbanding each linguistic competence (reading, writing, listening and speaking) within the post-test to determine which one was significantly different, the writing skill presented a significant level (p = 0.040, thus p < 0.05), in which the experimental group obtained better mean results than the control group, as observed in Table 6, while the rest of the skills presented no significant mean differences between the control group and the experimental group (p < 0.05).

Table 6.

Group statistics within the linguistic competence skills post-test.

When considering the comparison within each group from the pretest to the post-test, both groups improved considerably from the pretest to the post-test. In this sense, the Paired Samples test shows how the control group and the experimental group means were significantly different from the pretest to the post-test (p < 0.001 for both of them, while t = −6.931 and t = −8.948, respectively). Thus, gamification and the traditional methodology improved students’ linguistic competence significantly.

3.4. Emotions towards the English Subject

Concerning qualitative data, the emotions towards the English subject interview had some common answers in the pretest for the experimental group and the control group (that is why those responses are combined), having differences after the didactic intervention from the control group’s answers for some of the questions. In this sense, a few answer examples given in the pretest can be observed:

- -

- For question 1: Do you like being in English class? What do you like the most?

- ○

- Most of the answers from the experimental group and the control group were “Yes. I like English class. What I like the most is the activities”. Nevertheless, only a few people answered, “Not much, but I like the activities”.

- -

- For question 2: When the teacher speaks English, do you understand her? How does it make you feel?

- ○

- Most of the answers from the experimental group and the control group were “I understand her sometimes. That makes me feel a bit nervous”. Nevertheless, only a few people answered, “Yes, I understand her properly and that makes me feel good”.

- -

- For question 3: What do you think of the activities in English class? Is there something boring?

- ○

- Most of the answers from the experimental group and the control group were “I really enjoy the games, but the book is very boring”. Nevertheless, only a few people answered, “As the activities are good, there is nothing boring for me”.

- -

- For question 4: Do you like participating in class? Why?

- ○

- Most of the answers from the experimental group and the control group were “Yes, I do because the activities are enjoyable”. Nevertheless, only one student answered, “Not really because they are boring”.

- -

- For question 5: Do you understand all the activities? Why?

- ○

- Most of the answers from the experimental group and the control group were: “I understand most of them because I find them easy”. Nevertheless, only a few people answered, “I do not really understand them because they are a bit difficult”.

- -

- For question 6: What do you use when you study English at home? Is it boring for you?

- ○

- Most of the answers from the experimental group and the control group were “I use the book to study, and I find it very boring”. Nevertheless, only a few people answered, “I use the book and some sheets to study and it does not make me feel bored”.

The emotions towards the English subject interview had some interesting answers in the post-test with some different results for the experimental group and the control group, as shown in the next answer examples:

- -

- For question 1: Do you like being in English class? What do you like the most?

- ○

- All answers from the experimental group had a common result: “Yes. I love being in class. What I have liked the most is the games, the badges and the points”.

- ○

- Most of the answers from the control group were “Yes. I like English class. What I have liked the most is the games”. Nevertheless, only one student answered, “More or less, but I liked playing games”.

- -

- For question 2: When the teacher speaks English, do you understand her? How does it make you feel?

- ○

- Most of the answers from the experimental group were “I understand her sometimes and it made me feel good”. Nevertheless, only one student answered, “I do not understand some things and it makes me feel nervous because I can see other people understand her but me”.

- ○

- Most of the answers from the control group were “I understand her sometimes and it has made me feel normal”. Nevertheless, only a few people answered, “More or less and that makes me feel so-so”.

- -

- For question 3: What do you think of the activities in English class? Is there something boring?

- ○

- All of the answers from the experimental group had a common result: “The activities were very cool and I have not felt bored at any moment”.

- ○

- Most of the answers from the control group were “The activities were kind of good, but the book was a bit boring”. Nevertheless, a few students answered “The activities were good, so I did not feel bored”.

- -

- For question 4: Do you like participating in class? Why?

- ○

- All the answers from the experimental group had a common result: “Yes, I do because they are super cool”.

- ○

- Most of the answers from the control group were: “Yes, I do because the activities were fun”. Nevertheless, one student answered, “I have only participated sometimes because I did not like the games on some occasions”.

- -

- For question 5: Do you understand all the activities? Why?

- ○

- All the answers from the experimental group had a common result: “Yes, I do because they are very cool and easy to understand”.

- ○

- Most of the answers from the control group were “I understand the activities sometimes because they are easy to understand”. Nevertheless, only a few people answered, “More or less because they are a bit difficult to understand”.

- -

- For question 6: What do you use when you study English at home? Is it boring for you?

- ○

- All the answers from the experimental group had a common result: “I have used the online games and they were very cool, so I did not feel bored with them”.

- ○

- Most of the answers from the control group were: “I did not study that much at home these days”. Nevertheless, only a few people answered, “I used the book at home and it made me feel very bored”.

Table 7 shows a brief summary of the most common answers given in both the pretest and the post-test, so that a comparison can be conducted at a glance.

Table 7.

The most common answers in regard to the qualitative data in the pretest and post-test.

Thus, a variety of answers were given by both groups. However, in the pretest, most of the students of both groups had similar answers, but they changed slightly in the posttest after the didactic intervention application. Nevertheless, there was no significant contrast in the answers after the application of gamification due to the methodology employed by the current English teacher, since she is a teacher who normally combines some games with traditional methodology in her classes.

4. Discussion

The objective of this didactic intervention programme, called Amonglish us, was to investigate the impact of gamification on students’ linguistic competence, motivation, attentional focusing, and emotions towards the English subject. Thus, an eight-session didactic intervention programme, which was based on the characteristics of gamification, was conducted in the experimental group, while the control group followed a traditional methodology.

In this sense, the pretest showed general but low knowledge about the concepts to be acquired (linguistic competence) in both groups, as well as the motivation, inattention, and emotions towards the English subject. Nevertheless, after the implementation of the didactic intervention programme, the post-test showed interesting results for the experimental group’s linguistic competence, indicating significant mean differences in the posttest, thus answering research question 5, that gamification can positively impact students’ linguistic competence. Specifically, the writing skill improved significatively as the gamified experience portrayed online activities and follow-up tasks to complete at home, thus allowing them to practise this skill intensively. Furthermore, both the control and the experimental group showed improvements from the pretest to the post-test for linguistic competence. Henceforth, research question number 1 can be answered, since improvements in students’ performance from the pretest to the post-test occurred after the gamification implementation.

Although no significant mean differences can be observed between the control group and the experimental group in terms of attention, it is relevant to remark how both groups’ means are significantly different from the pretest to the post-test, indicating significant improvements in students’ attention. In this sense, research question 2 is answered: gamification can improve students’ attention significantly.

In qualitative terms, gamification had a positive impact on students’ emotions towards English, since students from the experimental group showed more positive encouragement towards the subject, increasing their active participation in class and lessening the negative inclination about the mistakes encountered, as they were solved immediately through feedback. In this vein, research question 3 is taken into account: gamification can enhance students’ attitudes towards the English subject.

Regarding motivation, no significant mean differences existed between the experimental group and the control group after the didactic intervention program implementation. Notwithstanding, the experimental group’s motivation significantly increased from the pretest to the post-test thanks to gamification, probably due to the badges employed, the cooperative work used, the tasks considered within students’ interests, and the online games employed for the follow-up content practice. However, these considerations were not taken into account within the control group’s methodology, showing no significant improvement from the pretest to the post-test. Henceforth, research question 4 is answered: gamification can benefit students’ motivation significantly, as observed in the present project.

All in all, significant differences between the control group’s results and the experimental group’s results after the didactic intervention programme implementation were observed, specifically in terms of linguistic competence, thus answering research question number 6. Notwithstanding, it has been portrayed that gamification, particularly the present proposal, improves students’ performance (research assumption 1), attentional processes (research assumption 2), interest towards the English subject (research assumption 3), motivational attitudes (research assumption 4), and linguistic competence (research assumption 5).

5. Conclusions

It is beyond dispute that “educative opportunities and succeeding chances in life are reflected by the pedagogic system” [29] (p. 5) In this vein, the educative context should aim at the development of methodological approaches and practices that make students develop an interest in learning languages in an interactive, dynamic, and enjoyable manner. Within these considerations, the present project allows students to develop an interest and positive attitudes towards the English subject but, more importantly, towards the English language, when planning activities and tasks based on their personal interests, so that emotions are engaged, thus providing favourable outcomes.

This project aimed to investigate the effects of Among us game-based gamification on language competence, motivation, attention, and attitudes towards the English subject. In this process, the proposal designed involved conducting different tasks to obtain points set in ClassDojo through badges related to specific items to be achieved (spoken English, helping others, completing tasks, day-to-day improvements, and points obtained). In this vein, students’ motivation was always kept high when designing materials related to their own interests: Among us.

Even though this proposal has copious potential due to the impactful benefits undertaken within a short period of time, some difficulties were encountered, which need to be considered for future studies. Thus, future research focusing on a long-term two-methodology combination, in which one of them is gamification, should be considered. This approach would allow students to practise the writing and listening skills more, as they were two of the main skills that had less practise in the didactic intervention implementation. Thus, students would develop high motivation, attention, and positive emotions towards the English subject using this methodology through the practise of some of the main English skills with a more traditional methodology with the help of the book (if required).

Another approach to consider is the selection of specific games according to students’ feelings. In other words, we should determine how certain games, which depend on the students’ groupings, could influence specific emotions. Along these lines, competition is one of the main factors involved in this didactic intervention shown in the ClassDojo interface and some of the online games’ leaderboards. Thus, would emotions and motivation decrease during competition between students? Would the anger feeling and disappointment of not winning take over in some students? These lines of future investigation should be considered, so that the foundation of the games created can improve students’ emotions, instead of obtaining the opposite effect.

Furthermore, students were asked about their extra-curricular education in English. Hence, a future study comparing students who attend an academy and those who do not may present interesting new results. In fact, an after-intervention statistical study was conducted considered this variable using SPSS software. In the pretest, a significant difference was observed between students who were attending extra-curricular English classes (obtaining better results) and those who were not. However, in the post-test, this significant difference decreased considerably. Thus, it can be said that this didactic intervention program helped balance us the inequalities between these two groups. Therefore, a future approach should be considered to study the maximum balance between these two groups in a long-term program. Would gamification be able to stop these inequalities and help students who might not be able to afford extra-curricular classes?

Funding

This investigation has been developed thanks to the funding and support received by UCLM.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the acceptance of the school members, along with the parental tutors and the students considered at the school to participate in the project, bearing in mind students’ data protection and confidentiality.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study, along with their parental tutors.

Data Availability Statement

Research data are unavailable due to privacy restrictions from students’ tutors.

Acknowledgments

This investigation is a part of the applied research project “Mejora de los procesos de enseñanza de lenguas: protocolos de actuación y experimentación para la enseñanza bilingüe familiar (PLF), escolar (AICLE) y universitaria (EMI) y para la innovación didáctica” (2022-GRIN-34455 reference) subsided by UCLM and FEDER. I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Professor Esther Nieto Moreno de Diezmas for the thoughtful recommendations, comments and guidance on this investigation. Besides, I would like to also extend my sincere thanks to the Department of Modern Languages of the UCLM. Lastly, I would like to thank the state school in consideration and its educative members, who were very kind and willing to help to make this educative intervention research possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

QR codes for sources and materials used: (a) QR code for the Amonglish us presentation for students, (b) QR code for the extra worksheet for students, (c) QR code for the pretest–post-test tests for the Amonglish us didactic intervention, (d) QR code for the Right or wrong? game, (e) QR code for Game 1, (f) QR code for Game 2.

Figure A2.

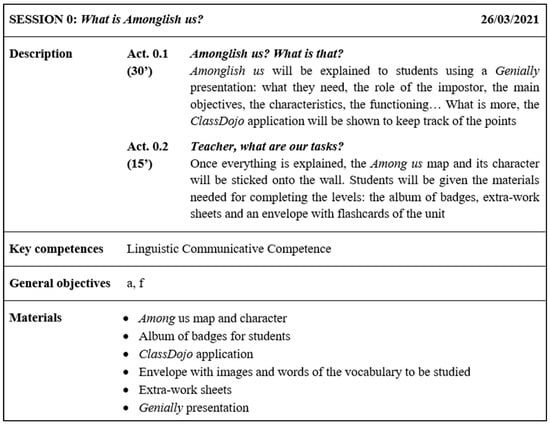

Session 0 explanation and connection with the curriculum in force.

Figure A3.

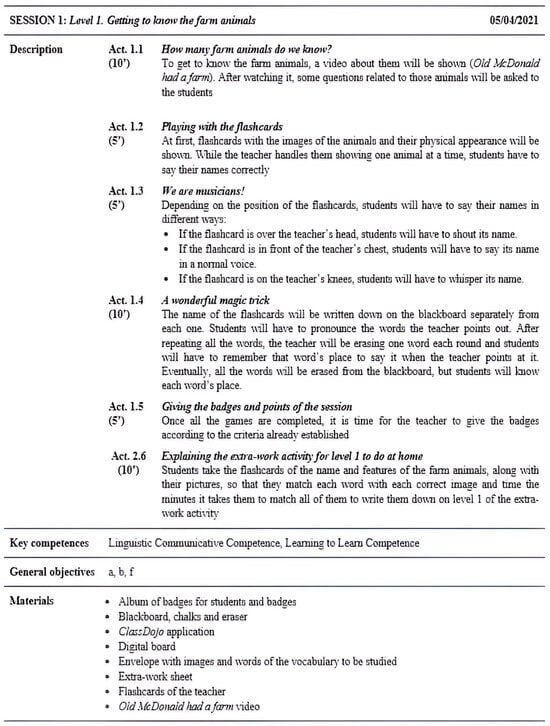

Session 1 explanation and connection with the curriculum in force.

Figure A4.

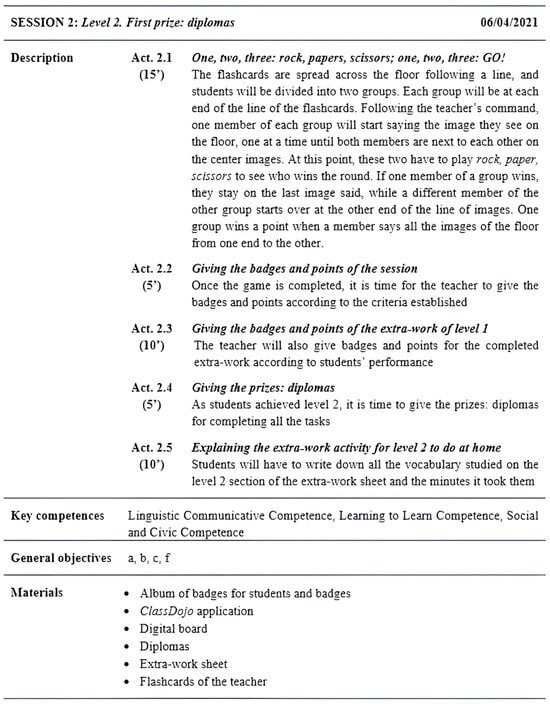

Session 2 explanation and connection with the curriculum in force.

Figure A5.

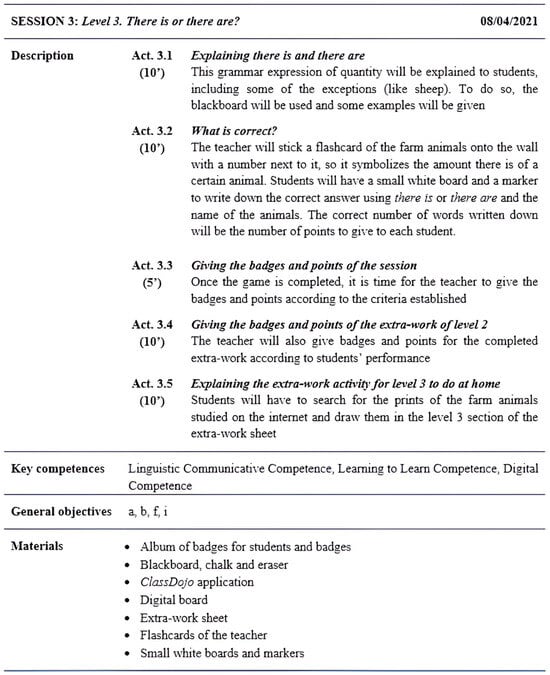

Session 3 explanation and connection with the curriculum in force.

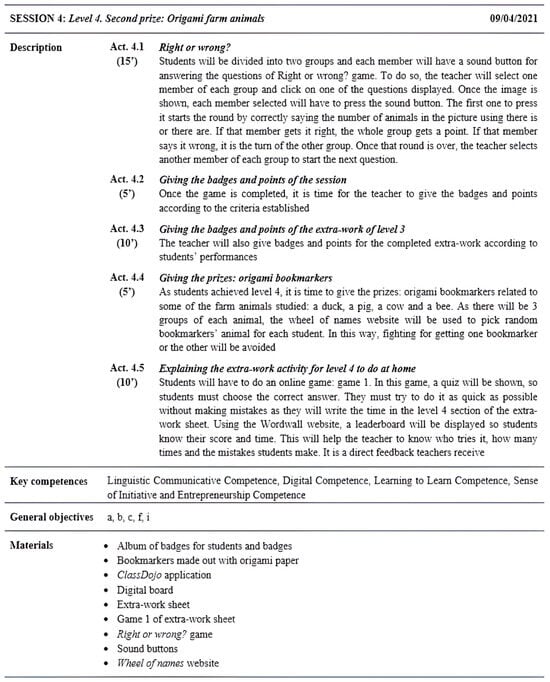

Figure A6.

Session 4 explanation and connection with the curriculum in force.

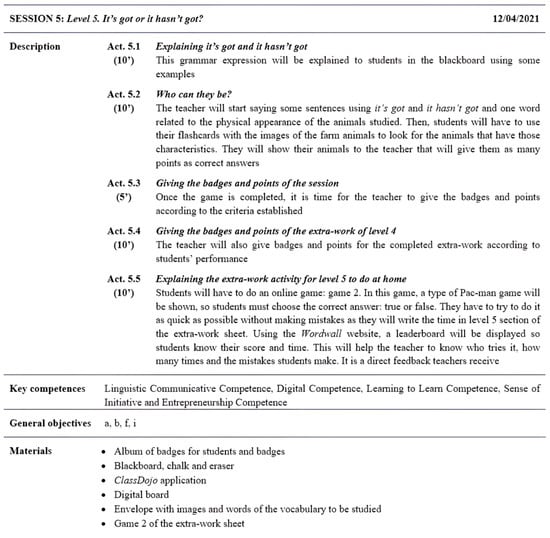

Figure A7.

Session 5 explanation and connection with the curriculum in force.

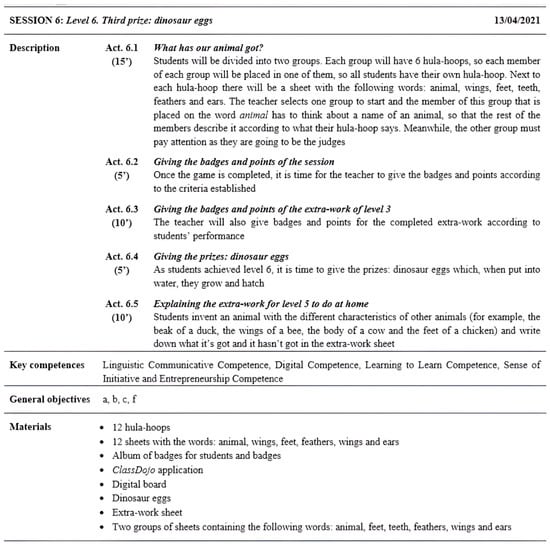

Figure A8.

Session 6 explanation and connection with the curriculum in force.

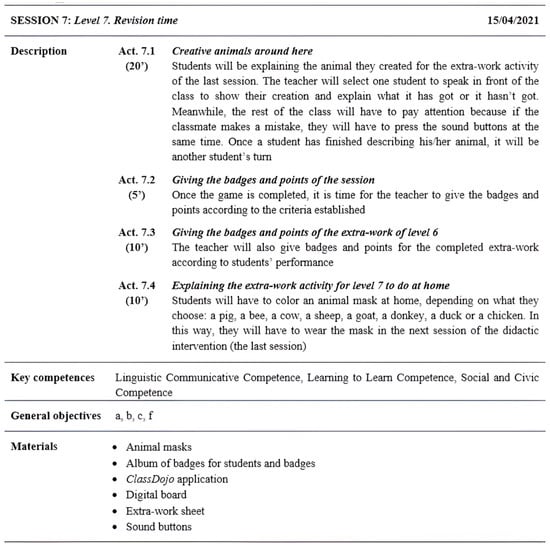

Figure A9.

Session 7 explanation and connection with the curriculum in force.

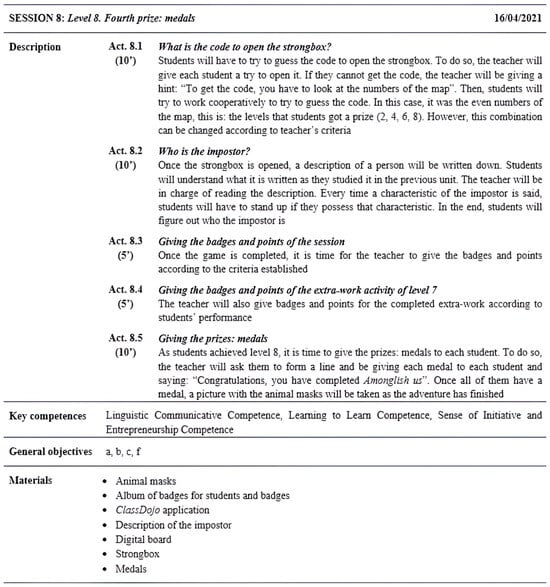

Figure A10.

Session 8 explanation and connection with the curriculum in force.

References

- Toro, A.; Arguis, M. Metodologías activas. A Tres Bandas 2015, 38, 69–77. [Google Scholar]

- Méndez, Z. Aprendizaje y Cognición, 9th ed.; EUNED: San José, Costa Rica, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sarramona, J. Teoría de la Educación, 2nd ed.; Planeta: Barcelona, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo-Bonilla, R. Los Juegos de Integración en el Desarrollo Social de la Escuela Básica General Juan Lavalle. Final Year Project—Educación Parvularia e Inicial, Carrera Educación Parvularia e Inicial-Universidad Nacional de Chimborazo, Chimborazo, 6th March 2017. Available online: http://dspace.unach.edu.ec/handle/51000/3549 (accessed on 6 May 2022).

- Casado, M. La Gamificación en la Enseñanza de Inglés en Educación Primaria. Final Year Project—Didáctica del Inglés, Grado en Educación Primaria—Universidad de Valladolid, Valladolid, 2016. Available online: http://uvadoc.uva.es/handle/10324/18538 (accessed on 6 May 2022).

- Sevilla-Vallejo, S.; García-Moreno, A. El método IBI en la enseñanza de ELE. Aplicación de la gamificación en el Camino de Santiago. Foro Profesores E/LE 2019, 243–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín Cruz, N.; Martín Pérez, V.; Trevilla Cantero, C. Influencia de la motivación intrínseca y extrínseca sobre la transmisión de conocimiento. El caso de una organización sin fines de lucro. CIRIEC-España Rev. Econ. Pública Soc. Coop. 2009, 66, 187–211. [Google Scholar]

- Meneses, M.; Mongue, M.A. El juego en los niños: Enfoque teórico. Rev. Educ. 2001, 25, 113–124. [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo, P.M. La plataforma de aprendizaje Kahoot en las clases de ELE. In Investigación e Innovación en la Enseñanza de ELE: Avances y Desafíos; Cea, A.M., Pazos-Justo, C., Otero, H., Lloret, J., Moreda, M., Dono, P., Eds.; Húmus: Famalicäo, Portugal, 2018; pp. 385–395. [Google Scholar]

- García-Casaus, F.; Cara-Muñoz, J.F.; Martínez-Sánchez, J.A.; Cara-Muñoz, M.M. La gamificación en el aula como herramienta motivadora en el proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje. Logía Educ. Física Deporte: Rev. Digit. Investig. Cienc. Act. Física Deporte 2021, 1, 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- García, F.; Doménech, F. Motivación, aprendizaje y rendimiento escolar. Rev. Española Motiv. Emoción 1997, 1, 55–65. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10234/158952 (accessed on 7 April 2022).

- Mayer, R. Rote Versus Meaningful Learning. Theory Pract. 2002, 41, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiyo, Y.; Nokham, R. The effect of Kahoot, Quizizz and Google Forms on the student’s perception in the classrooms response system. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Digital Arts, Media and Technology, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 1–4 March 2017; pp. 178–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunyongying, P. Gamification: Implications for curricular design. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2014, 6, 410–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, A.; School of Interactive Arts and Technology, Simon Fraser University, Surrey, BC, Canada; Neustaedter, C.; School of Interactive Arts and Technology, Simon Fraser University, Surrey, BC, Canada. Personal communication, 2013.

- Garris, R.; Ahlers, R.; Driskell, J. Games, motivation, and learning: A research and practice model. Simul. Gaming 2002, 33, 441–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, F.; García, O.; Martín, M. La Gamificación Como Recurso Para la Mejora del Aprendizaje del Inglés en Educación Primaria. Red Investig. Sobre Liderazgo Mejor. Educ. 2018, 466–468. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10486/682944 (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- González, A. La Gamificación Como Elemento Motivador en la Enseñanza de una Segunda Lengua en Educación Primaria. Master’s Thesis, Universidad de Burgos, Burgos, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gargallo, P. Una experiencia de gamificación con tablets para potenciar el inglés en el aula de infantil. Master’s Thesis, Universitat Jaume I, Castellón de la Plana, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cejudo, J.; Losada, L.; Pena, M.; Feltrero, R. Programa “aislados”: La gamificación como estrategia para promover el aprendizaje social y emocional. Voces Educ. 2019, 155–168. Available online: https://www.revista.vocesdelaeducacion.com.mx/index.php/voces/article/view/218 (accessed on 12 April 2022).

- Ato, M.; López, J.J.; Benavente, A. Un Sistema de clasificación de los diseños de investigación en psicología. An. Psicol. 2013, 29, 1038–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuPaul, G.J.; Power, T.J.; Anastopoulos, A.D.; Reid, R. ADHD Rating Scale—IV: Checklists, Norms, and Clinical Interpretation; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Pekrun, R.; Goetz, T.; Perry, R.P. Academic emotions in students’ self-regulated learning and achievement: A program of quantitative and qualitative research. Educ. Psychol. 2002, 37, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero, L.; Alonso Tapia, J. El cuestionario MAPE-II. In Motivar en la Adolescencia: Teoría, Evaluación e Intervención; Alonso, J., Ed.; Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad Autónoma: Madrid, Spain, 1992; pp. 205–232. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso Tapia, J.; Sánchez, J. El cuestionario MAPE-I: Motivación hacia el aprendizaje. In Motivar en la Adolescencia: Teoría, Evaluación e Intervención; Alonso, J., Ed.; Publicaciones de la Universidad Autónoma: Madrid, Spain, 1992; pp. 53–91. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso Tapia, J.; Montero, I.; Huertas, J.A. Evaluación de la Motivación en Sujetos Adultos. El Cuestionario MAPE-3; Facultad de Psicología, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Connell, J.P. Perceived locus of causality and internalization: Examining reasons for acting in two domains. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 749–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco, J. Evaluación de la Motivación Académica en Niños de Primer Ciclo de Educación Infantil. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de León, León, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Vélez-Miranda, M.J.; San Andrés-Laz, E.M.; Pazmiño-Campuzano, M.F. Inclusión y su importancia en las instituciones educativas desde los mecanismos de integración del alumnado. Rev. Arbitr. Interdiscip. Koinonía 2020, 5, 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).