A Holistic Model for Disciplinary Professional Development—Overcoming the Disciplinary Barriers to Implementing ICT in Teaching

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Study Context

1.2. Stages of Assimilating Technology into Teaching

1.3. Incorporation of ICT Tools into Language Instruction

The Integration of ICT Tools into the Teaching of Writing

1.4. Barriers to ICT Integration

1.5. Teachers’ Professional Development

1.6. Present Research

Research Questions

2. Method

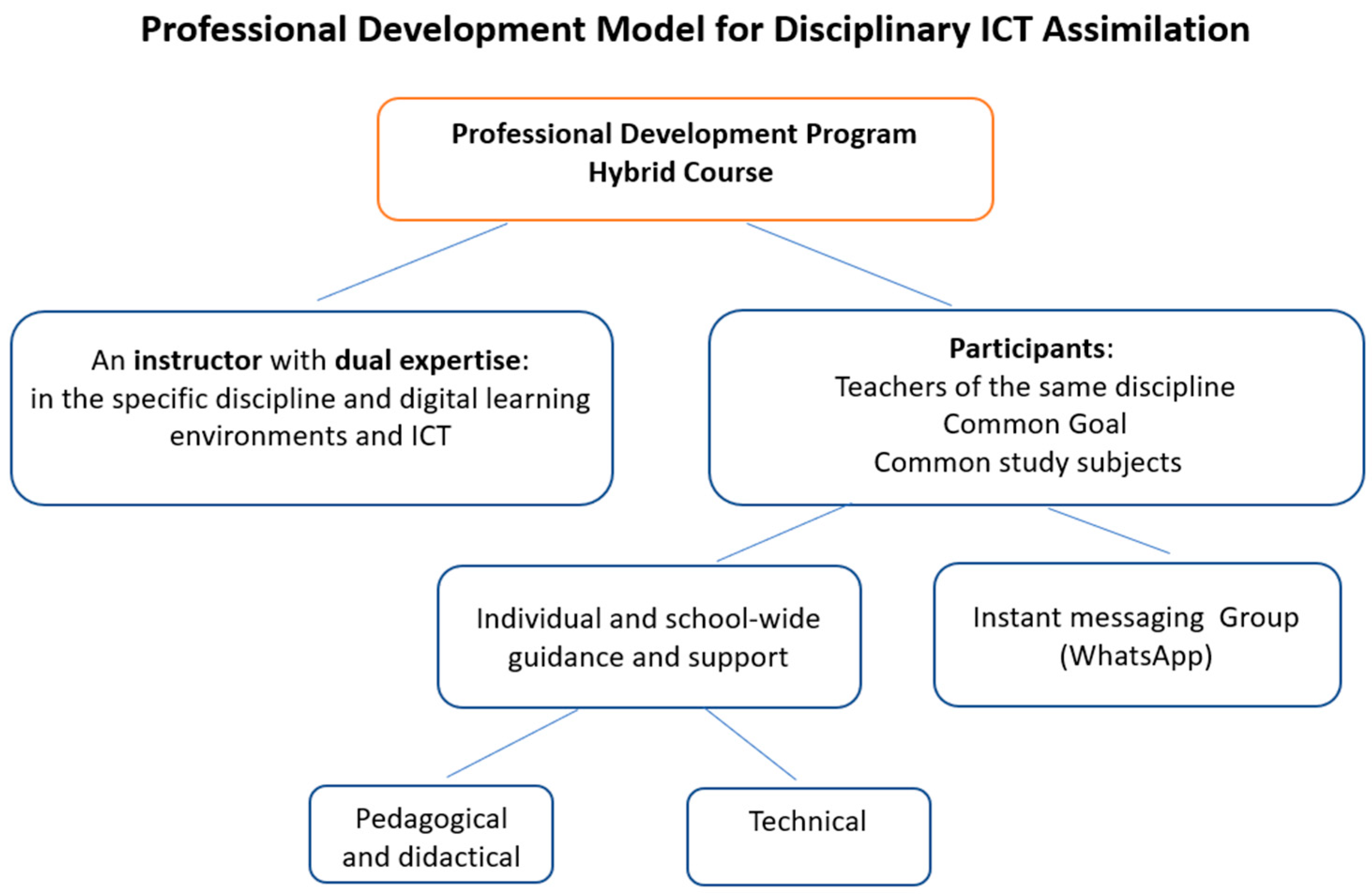

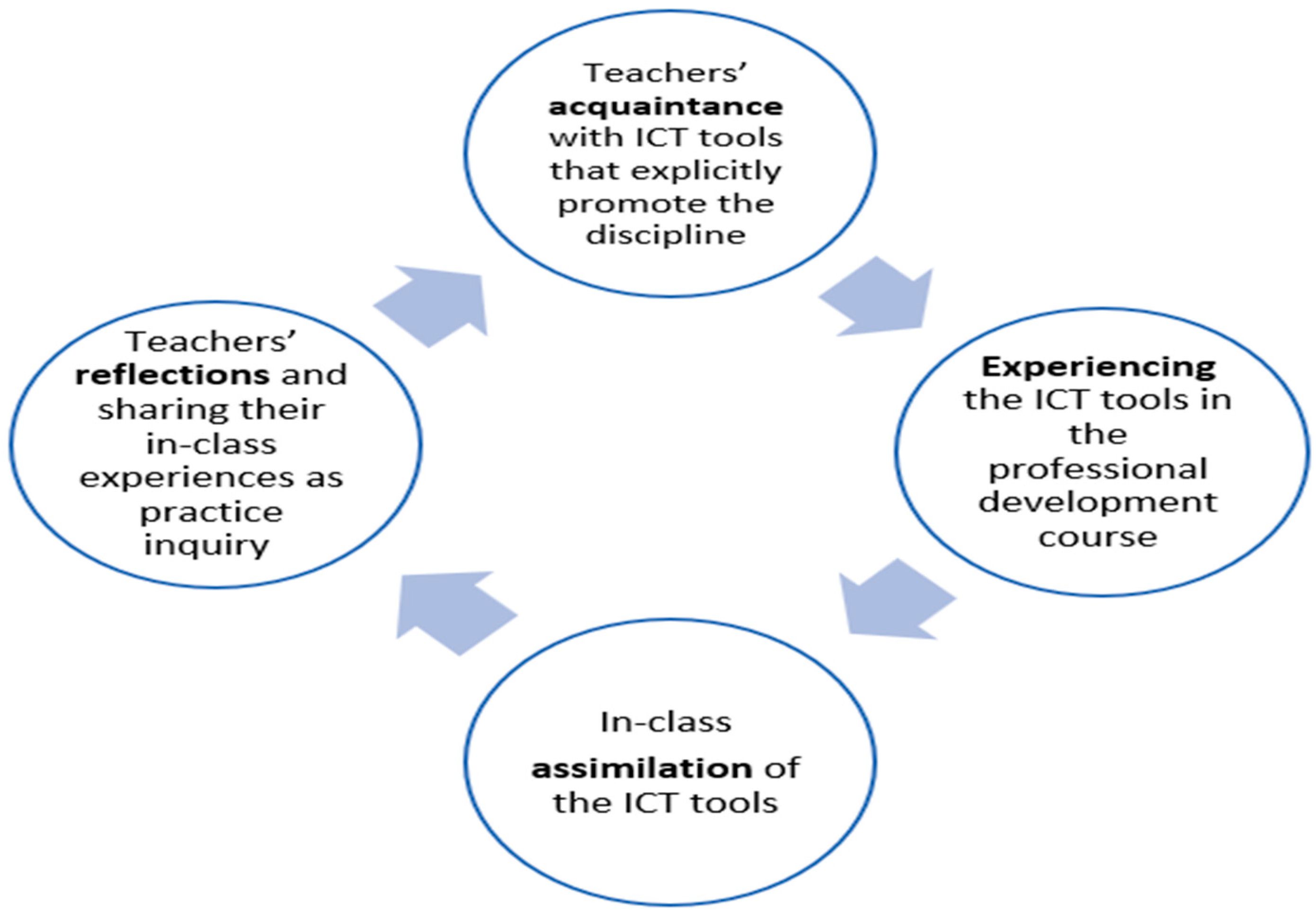

2.1. Conceptual Framework and Description of the Professional Development Model

2.1.1. Professional Development Model

2.1.2. Structure of the Course

2.1.3. Research Tool

2.1.4. Participants

2.1.5. Research Procedure

3. Findings

3.1. First Research Question

3.1.1. External Barriers

“What helped was that the fear disappeared. I mean the fear of the computer field. I learned how to explain and make it accessible, and I saw that the demon is not so terrible. I saw how XXX [the instructor] acted, how he explained clearly and demonstrated to us [our] study materials.”

“We were taught tools that we can use in the language classes. I was taught all kinds of tools in the past as well, but this time it was different. In the course, we had an amazing instructor, and when I needed help in the afternoon or the morning, I had someone to turn to. I had instructors at my disposal, and they were in full coordination with the instructor in the course. For example, I composed a test using the side-by-side option—the text on the left and the questions on the right. I got into trouble, but I had someone to turn to. This support beyond the scope of the course is very helpful. I really liked the fact that it doesn’t end when the course ends. It made me not be afraid, to dare and try.”

“Technology and I are not friends, but I realized that the technological challenge is here, whether we want it or not. The direction is going there, and I can’t run away from it. I was very afraid of the technical matters. I was afraid that I would get into trouble during the class, that I wouldn’t know how to use the technology properly, and that I would lose the students. But to my surprise, I was able to face the technological challenge thanks to everything I received in the course. We experimented with everything, even after the course hours. We had a WhatsApp group I could consult, and I could also invite an instructor to the school to help me deal with the technical problems.”

“Our school has portable computer carts. I never ordered them because I was afraid that I wouldn’t be able to manage. I gained confidence in the professional development. I felt that I could deal with the fear I had. The first three times I asked the instructor to be with me. She guided and helped me. Later, I already activated everything by myself.”

3.1.2. Internal Barriers

“Until I started the course, I thought I needed technology [in class] to diversify the teaching. I used presentations and videos, but here I realized that diversity is not the main thing at all. The tools I received from the instructor, who was also a language teacher himself, directly touched my field. For example, in the field of writing, the wiki that taught me can greatly help me in promoting writing and also in checking the texts that are so difficult for me. So we should get on the train early and not late.”

“As soon as the instructor was so professional and introduced us to computerized tools that are suitable for my field, it aroused my great interest. I realized that I can also use more recent, relevant, and accurate materials. It also saves me a lot of time in building materials, and most importantly, helps me to promote the students. I took it upon myself to lead the entire team to use the tools we received.”

“You can see the sparkle in the students’ eyes. There is more dynamism in the teaching. You see the interest and curiosity and especially the progress in writing. It does not become an exhausting and tiring 45-min class. Working on the computer made them write during the class, correct and rewrite. They could compare their versions on the wiki. It wasn’t in my regular class. What else impressed me was that they continued to talk about it at home. An interest was created, and what happens in the classes is relevant to them.”

“Honestly, I didn’t really understand why I needed ICT in my classes. I’m considered a good teacher even without it, but the instructor in the course managed to convince me that the use of ICT is necessary for my field. He himself teaches language in classes. The examples he gave and the tools he showed made it clear to me that I had to use it in teaching, not occasionally but regularly.”

“Sometimes I get mad at myself, why did I just now remember, but to be honest, I was in several training courses at school where we were taught in general. This time it was different. The whole focus was on teaching the language and especially writing. We were shown, for example, all kinds of computerized environments that can promote writing, make comments, and also write collaboratively. It made me realize that there is no turning back.”

“I experienced a course different from what I had known until now. Everything was relevant. We were taught things related to our field: reading and writing. Everything I learned, I could apply in the classrooms. When I encountered difficulty or did not understand something, I had someone to talk to both within the course and outside of the course hours. In the WhatsApp group, we shared ideas for lessons. It was very difficult for me at first, but the course instructor was also available beyond the course hours.”

3.2. Second Research Question

The Degree of Effectiveness in Each of the Support Components of the Model

3.3. Third Research Question

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Limitations and Future Research

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Questions for the Interviewees

- Describe to me the professional development in which you participate. What does it include? What are its components? What are its highlights?

- What is the most significant thing you have experienced in the professional development? Tell me about a significant experience from the course you are participating in.

- What areas of knowledge and language teaching did this course promote in particular?

- Has the course changed your way of teaching the first language subject? If so, how?

- Does the course contribute to the teaching of a first language, and if so, in which areas of the field of knowledge?

- If you had to describe two things that distinguish the professional development in which you participate, what would you mention?

- Can the tools you are exposed to advance students in the field of knowledge? Where? How? Explain and give an example.

- Have you previously participated in a course dealing with ICT? If so, how is this course different from the ICT course you participated in before?

- What are your views on ICT integration in the first language teaching field of knowledge?

- Has your attitude toward ICT in your discipline changed as a result of your participation in the professional development? Please provide an explanation.

Appendix B. Mixed Online Questionnaire (Closed- and Open-Ended Questions)

- (a)

- “To what extent is the course guided by ICT professionals who are proficient in the field of knowledge more effective than a course guided by ICT professionals only?” (answered on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 6 (to a very large extent);

- (b)

- “And why?” (open question);

- (c)

- “To what extent did the course contribute to your ability to use ICT tools in teaching writing in the classroom?” (answered on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 6 (to a very large extent));

- (d)

- “What changes would you make in order to integrate an ICT tool into the teaching of Hebrew?” (open question);

- (e)

- “What would you improve in order to integrate ICT tools into Hebrew teaching?” (open question);

- (f)

- “Would you like to specialize in a continuation course next year?” (yes/no); (g) “Would you recommend this course to other Hebrew teachers in this format?” (yes/no).

References

- Ghalib, B. Integration of Information and Communication Technologies in the Teaching-Learning Process of Biology within Middle School Education from Israel. 2021. Available online: https://ust.upsc.md/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/BG_Rezumat_eng.pdf (accessed on 23 October 2023).

- Magen-Nagar, N.; Rotem, A.; Inbal-Shamir, T.; Dayan, R. The effect of the national ICT plan on the changing classroom performance of teachers. In Proceedings of the 9th Chais Conference for the Study of Innovation and Learning Technologies, Raanana, Israel, 11–12 February 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dhawan, S. Online learning: A panacea in the time of COVID-19 crisis. J. Educ. Technol. Syst. 2020, 49, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paños-Castro, J.; Arruti, A.; Korres, O. COVID and ICT in primary education: Challenges faced by teachers in the Basque country. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simamora, R.M. The challenges of online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: An essay analysis of performing arts education students. Stud. Learn. Teach. 2020, 1, 86–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilic, P. Understanding the Challenges of Leveraging Information and Communications Technology in Education. In Handbook of Research on Teacher and Student Perspectives on the Digital Turn in Education; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2022; pp. 94–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limna, P.; Jakwatanatham, S.; Siripipattanakul, S.; Kaewpuang, P.; Sriboonruang, P. A review of artificial intelligence (AI) in education during the digital era. Adv. Knowl. Exec. 2022, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Avidov-Ungar, O.; Amir, A. Development of a teacher questionnaire on the use of ICT tools to teach first language writing. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2018, 31, 675–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avidov-Ungar, O.; Amir, A. Use of digital tools by high school teachers teaching writing participating in an intervention program to reduce the “discipline block”. In Proceedings of the Society for Information Technology Teacher Education International Conference, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 18–22 March 2019; Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education: Chesapeake, VI, USA; pp. 1489–1493. [Google Scholar]

- Avidov-Ungar, O. The professional learning expectations of teachers in different professional development periods. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2023, 49, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, P.S. Examining current beliefs, practices and barriers about technology integration: A case study. TechTrends 2016, 60, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luterbach, K.J.; Brown, C. Education for the 21st century. Int. J. Appl. Educ. Stud. 2011, 10, 14–32. [Google Scholar]

- Tondeur, J.; van Braak, J.; Ertmer, P.A.; Ottenbreit-Leftwich, A. Understanding the relationship between teachers’ pedagogical beliefs and technology use in education: A systematic review of qualitative evidence. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2017, 65, 555–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.Y.; Scardamalia, M.; Zhang, J. Knowledge society network: Toward a dynamic, sustained network for building knowledge. Can. J. Learn. Technol. 2010, 36, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voogt, J.; Roblin, N.P. A comparative analysis of international frameworks for 21st-century competences: Implications for national curriculum policies. J. Curric. Stud. 2012, 44, 299–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonk, C.J. For openers: How technology is changing school. Educ. Leadersh. 2010, 67, 60–65. [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrino, J.W.; Hilton, M.L. (Eds.) Education for life and work: Developing transferable knowledge and skills in the 21st century. In Committee 011 Defining Deeper Learning and 21st Century Skills; National Research Council of the National Academies: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sandholtz, J.H.; Ringstaff, C.; Dwyer, D.C. Ensinando com tecnologia: Criando salas de aulas centradas nos alunos. In Teaching with Technology: Creating Student-Centered Classrooms; Artes Médicas: Sao Paulo, Brazil, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Aldosemani, T. Inservice Teachers’ Perceptions of a Professional Development Plan Based on SAMR Model: A Case Study. Turk. Online J. Educ. Technol.—TOJET 2019, 18, 46–53. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, K. Students’ computer literacy: Perception versus reality. Delta Pi Epsil. J. 2006, 48, 108–120. [Google Scholar]

- Fraillon, J.; Ainley, J. The IEA International Study of Computer and Information Literacy (ICILS). 2010. Available online: http://forms.acer.edu.au/icils/documents/ICILS-Detailed-Project-Description.pdf (accessed on 23 October 2010).

- Abraham, M.; Arficho, Z.; Habtemariam, T. Effects of training in ICT-assisted English language teaching on secondary school English language teachers’ knowledge, skills, and practice of using ICT tools for teaching English. Educ. Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 6233407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Soto, T.; Prendes-Espinosa, P. A Systematic Review on the Role of ICT and CLIL in Compulsory Education. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torsani, S. CALL Teacher Education: Language Teachers and Technology Integration; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vintoniv, M.; Tiutiuma, T. Use of ict tools in teaching syntax of Ukrainian language to philology students. Sci. J. Pol. Univ. 2022, 51, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Lin, C.H.; Zhang, D.; Zheng, B. Language teachers’ perceptions of external and internal factors in their instructional (non-) use of technology. In Preparing Foreign Language Teachers for Next-Generation Education; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2017; pp. 56–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warschauer, M.; Ware, P. Learning, change, and power: Competing Frames of Technology and Literacy. In Handbook of Research on New Literacies; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 215–240. [Google Scholar]

- Akhmedov, B.A. Use of Information Technologies in The Development of Writing and Speech Skills. Uzb. Sch. J. 2022, 9, 153–159. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett, E.J. Learning to Write: Some Cognitive and Linguistic Components; Center for Applied Linguistics: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, M.S.; Pavlou, P.A. Marketing in computer-mediated environments: Research synthesis and new directions. J. Mark. 2014, 78, 20–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharples, M.; van der Geest, T. (Eds.) The New Writing Environment: Writers at Work in a World of Technology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, C. Computers and the writing classroom: A look to the future. In Re-Imagining Computers and Composition; Hawisher, G.E., LeBlanc, P., Eds.; Heinemann: Portsmouth, NH, USA, 1992; pp. 7–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hawisher, G.E. Electronic meetings of the minds: Research, electronic conferences, and composition studies. In Re-Imagining Computers and Composition; Hawisher, G.E., LeBlanc, P., Eds.; Heinemann: Portsmouth, NH, USA, 1992; pp. 81–101. [Google Scholar]

- Amir, A.; Avidov-Ungar, O. What’s blocking the integration of technology in teaching? The disciplinary barrier. In Proceedings of the 12th Annual Education and Development Conference, Bangkok, Thailand, 1–10 February 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ertmer, P.A. Addressing first- and second-order barriers to change: Strategies for technology integration. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 1999, 47, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, K. Teaching and Learning with ICT Tools: Issues and Challenges. Int. J. Cybern. Inform. 2023, 12, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Kim, M.K.; Lee, C.; Spector, J.M.; DeMeester, L. Teacher beliefs and technology integration. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2012, 29, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, H. ISTE Standards for Educators: A Guide for Teachers and Other Professionals; International Society for Technology in Education: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hew, K.F.; Brush, T. Integrating technology into K-12 teaching and learning: Current knowledge gaps and recommendations for future research. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2007, 55, 223–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newhouse, C.P.; Clarkson, B.D. Using learning environment attributes to evaluate the impact of ICT on learning in schools. Res. Pract. Technol. Enhanc. Learn. 2008, 3, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrail, E. Teachers, technology, and change: English teachers’ perspectives. J. Technol. Teach. Educ. 2005, 13, 5–24. [Google Scholar]

- Yermekkyzy, A. Experiences and Challenges of Novice and Experienced English Teachers in Using ICT Applications. Master’s Thesis, Faculty of Education and Humanities, Suleyman Demirel University, Isparta, Türkiye, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolopoulou, K.; Gialamas, V. Barriers to ICT use in high schools: Greek teachers’ perceptions. J. Comput. Educ. 2016, 3, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertmer, P.A.; Ottenbreit-Leftwich, A.T.; Sadik, O.; Sendurur, E.; Sendurur, P. Teacher beliefs and technology integration practices: A critical relationship. Comput. Educ. 2012, 59, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, R.; Koran, J.; White, L. A beginning model to understand teacher epistemic beliefs in the integration of educational technology. In Proceedings of the Society for Information Technology Teacher Education International Conference, Savannah, GA, USA, 21 March 2016; Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education: Chesapeake, VI, USA; pp. 2050–2056. [Google Scholar]

- Barak, M.; Dori, Y.J. Enhancing undergraduate students’ chemistry understanding through project-based learning in an IT environment. Sci. Educ. 2005, 89, 117–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avidov-Ungar, O. A model of professional development: Teachers’ perceptions of their professional development. Teach. Teach. 2016, 22, 653–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolam, R. Professional learning communities and teachers’ professional development. In Teaching: Professionalization, Development and Leadership: Festschrift for Professor Eric Hoyle; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 159–179. [Google Scholar]

- Olsson, D. Improving Teaching and Learning Together: A literature Review of Professional Learning Communities; Karlstad University Studies: Karlstad, Sweden, 2019; pp. 4–41. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, H.; Ertmer, P.A. Teacher educators’ beliefs and technology uses as predictors of preservice teachers’ beliefs and technology attitudes. J. Technol. Teach. Educ. 2008, 16, 93. [Google Scholar]

- Borg, S. Evaluating the impact of professional development. RELC J. 2018, 49, 195–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragg, L.A.; Walsh, C.; Heyeres, M. Successful design and delivery of online professional development for teachers: A systematic review of the literature. Comput. Educ. 2021, 166, 104158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunzicker, J. Effective professional development for teachers: A checklist. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2011, 37, 177–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuijpers, J.M.; Houtveen, A.A.M.; Wubbels, T. An integrated professional development model for effective teaching. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2010, 26, 1687–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerrim, J.; Sims, S. The Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) 2018: June 2019. 2019; pp. 130–160. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5f6484c2e90e075a01d2f4ce/TALIS_2018_research.pdf (accessed on 23 October 2023).

- Mishra, P.; Koehler, M.J. Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A new framework for teacher knowledge. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2006, 108, 1017–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, M.; Hedberg, J.G.; Kuswara, A. A framework for Web 2.0 learning design. Educ. Media Int. 2010, 47, 177–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magen-Nagar, N.; Peled, B. Characteristics of Israeli school teachers in computer-based learning environments. J. Educ. Online 2013, 10, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampert, M. Learning teaching in, from and for practice: What do we mean? J. Teach. Educ. 2010, 61, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matherson, L.; Windle, T.M. What do teachers want from their professional development? Four emerging themes. Delta Kappa Gamma Bull. 2017, 83, 28. [Google Scholar]

- Chai, C.S.; Koh, J.H.L.; Tsai, C.C.; Tan LL, W. Modeling primary school pre-service teachers’ Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK) for meaningful learning with information and communication technology (ICT). Comput. Educ. 2011, 57, 1184–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConachie, S.M.; Petrosky, A.R. Engaging content teachers in literacy development. In Content Matters: A Disciplinary Literacy Approach to Improving Students’ Learning; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moje, E.B. Chapter 1 Developing socially just subject-matter instruction: A review of the literature on disciplinary literacy teaching. Rev. Res. Educ. 2007, 31, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yamaguchi, S.; Sukhbaatar, J.; Takada, J.I. The influence of teachers’ professional development activities on the factors promoting ICT integration in primary schools in Mongolia. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangrieken, K.; Meredith, C.; Packer, T.; Kyndt, E. Teacher communities as a context for professional development: A systematic review. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2017, 61, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avidov-Ungar, O.; Amir, A. Between generic digital literacy and disciplinary digital literacy: A pioneer study—First language teaching. In Proceedings of the ECER 2016, Dublin, Ireland, 22–26 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, B.; Warschauer, M.; Lin, C.H.; Chang, C. Learning in one-to-one laptop environments: A meta-analysis and research synthesis. Rev. Educ. Res. 2016, 86, 1052–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, S.; Keshavarzi, A.; Foroutan, M. The application of information and communication technologies (ICT) and its relationship with improvement in teaching and learning. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 28, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | male | 77 | 83.7 |

| female | 15 | 16.3 | |

| Education level | BA | 54 | 58.7 |

| MA | 38 | 41.3 | |

| Tenure | M = 13.75 [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45], S.D. = 9.40 | ||

| Total | 92 | 100.0 | |

| M | S.D. | N | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Support | Technical | 2.60 | 0.97 | 85 |

| Didactic and pedagogical | 2.64 | 0.95 | 81 | |

| WhatsApp groups | 3.25 | 1.00 | 65 | |

| Effectiveness of the course instructors | Training effectiveness due to language proficient IT professionals | 4.57 | 0.56 | 86 |

| Effectiveness of the entire model | 4.47 | 0.67 | 85 |

| Descriptive Statistics | Pearson Correlations | Paired t-Test Comparisons | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | S.D. | N | Technical Support | Didactic and Pedagogical Support | Whatsapp Groups Support | Technical Support | Didactic and Pedagogical Support | Whatsapp Groups Support | |

| Technical support | 2.53 | 0.94 | 81 | -- | -- | ||||

| Didactic and pedagogical support | 2.64 | 0.95 | 81 | −0.485 *** | -- | 0.614 | -- | ||

| WhatsApp groups support | 3.23 | 1.01 | 62 | −0.116 | 0.234 | -- | 3.072 ** | 4.437 *** | -- |

| Support | Effectiveness of the Course Instructors | Effectiveness of the Entire Model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technical | Didactic and Pedagogical | Whatsapp Groups | Training Effectiveness Due to Language Proficient IT Professionals | Overall Model Effectiveness | ||

| Effectiveness of the course instructors | Training effectiveness due to language proficient IT professionals | 0.219 * | −0.098 | −0.249 | -- | |

| Effectiveness of the entire model | Overall model effectiveness | 0.287 ** | 0.153 | −0.009 | 0.393 ** | -- |

| Seniority | ||

|---|---|---|

| Support | Technical | 0.466 ** |

| Didactic and pedagogical | −0.509 ** | |

| WhatsApp groups | −0.042 | |

| Effectiveness of the entire model | Training effectiveness due to language proficient IT professionals | 0.239 * |

| Overall model effectiveness | 0.147 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Amir, A. A Holistic Model for Disciplinary Professional Development—Overcoming the Disciplinary Barriers to Implementing ICT in Teaching. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 1093. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13111093

Amir A. A Holistic Model for Disciplinary Professional Development—Overcoming the Disciplinary Barriers to Implementing ICT in Teaching. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(11):1093. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13111093

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmir, Alisa. 2023. "A Holistic Model for Disciplinary Professional Development—Overcoming the Disciplinary Barriers to Implementing ICT in Teaching" Education Sciences 13, no. 11: 1093. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13111093

APA StyleAmir, A. (2023). A Holistic Model for Disciplinary Professional Development—Overcoming the Disciplinary Barriers to Implementing ICT in Teaching. Education Sciences, 13(11), 1093. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13111093