Prerequisites of Good Cooperation between Teachers and School Psychologists: A Qualitative Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. International and Historical Overview of School Psychologist–Teacher Relationships

2.2. School Psychologist–Teacher Relationships in the Czech Republic

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

3.2. Data Collection and Collection Tool

3.3. Analysis

“Substantive codes conceptualize the empirical substance of the area of research. Theoretical codes conceptualize how the substantive codes may relate to each other as hypotheses to be integrated into the theory”[36] (p. 55)

4. Results

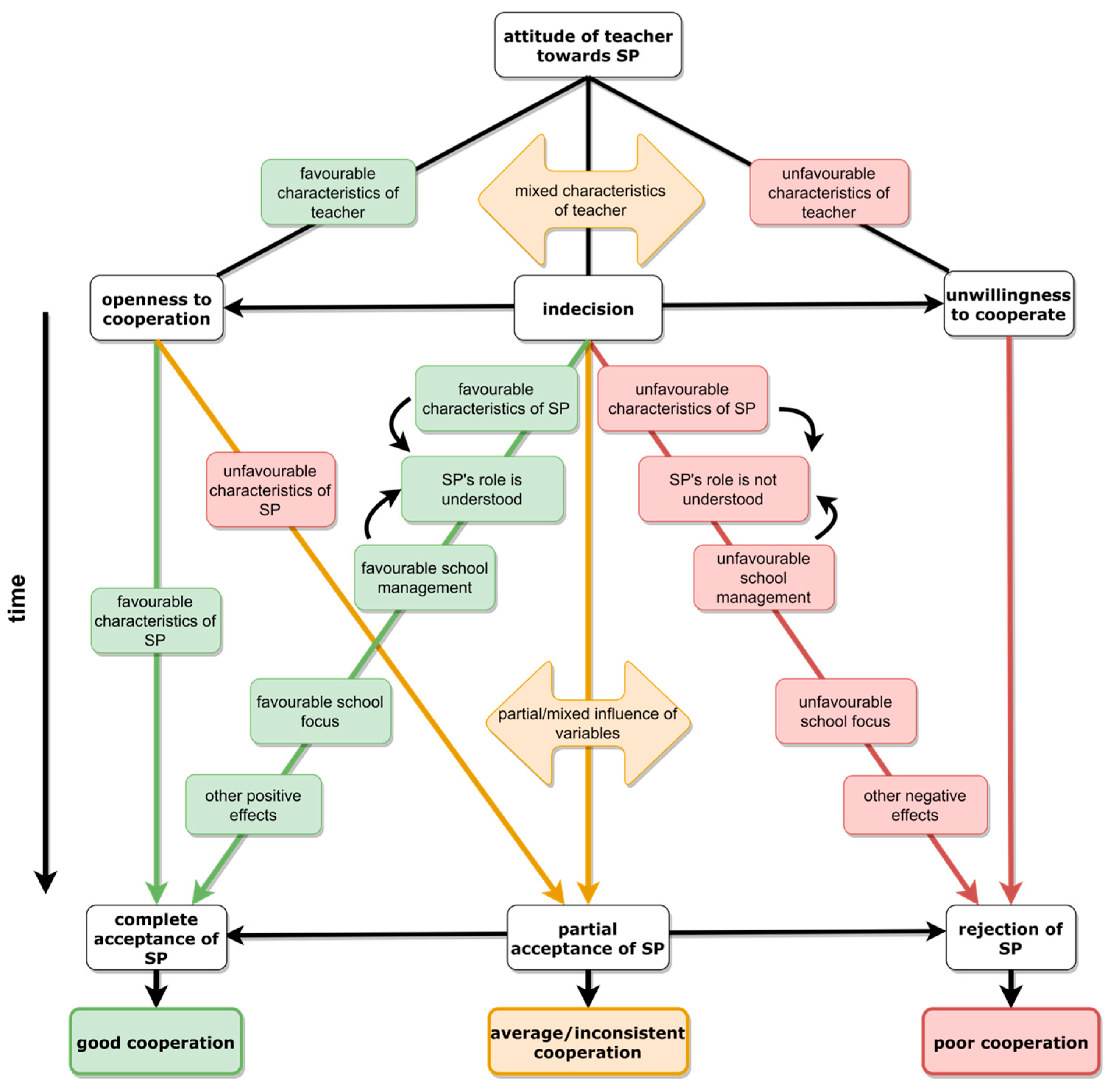

4.1. Attitude of Teacher—Level of Openness to Cooperation

I think that it’s about the people, you sort of have to sort it out on your own and accept that the times have changed. And all this is needed (meaning, the position of a school psychologist and other professionals at the school). I don’t think anyone can force us to think a certain way. I think that even if the psychologist tried, or even the principal, I think it’s in us, the teachers.(Teacher 8)

- 1.

- Openness to cooperate—accepting the attitude of the teacher without a tendency to judge, which potentially enables cooperation;

- 2.

- Indecision to cooperate—the middle value on the continuum, positioned between openness and unwillingness to cooperate. This occurs when the teacher has neutral attitudes that require other factors that would determine their final willingness to cooperate and establish trust to make a decision. Based on the respondents, these are the largest group;

- 3.

- Unwillingness to cooperate—a refusing or condemning attitude of the teacher, which leads the person to reject the institution of a school psychologist, either openly or, more often, internally. According to the respondents, each school typically has 1–3 teachers with this attitude.

4.2. Degree of Acceptance of School Psychologists and the Quality of Cooperation

- 4.

- Full acceptance of the school psychologist—the ideal case that leads to synergistic cooperation between the teacher and the school psychologist. In this process, both parties are viewed as equal partners;

- 5.

- Partial acceptance of the school psychologist—combines elements of acceptance and rejection in a varying intensity or frequency. This is an attitude somewhere in the middle of the spectrum that assumes that there are both positive and negative factors

- 6.

- Rejection of the school psychologist—in this case, the teacher did not come to trust the psychologist and refused to work with them or only worked with them when they were forced to.

4.3. Description of the Factors in the Model

Before we started training, it sort of felt like everybody was doing things on their own, or at least I felt that way. During the training, we were encouraged a lot to share, to show what we’re working on, to perform lessons in front of each other and show our work to each other a bit better. That also led to more sitting in on classes and the fact that we’re not as ‘shy’ in front of each other, that we sort of just go see what people are up to. And they don’t go there to judge, but to get inspired […] And I think that’s something that the school should promote, because the relationship between a teacher and psychologist won’t change unless other things are sorted out first. In my opinion, it’s about the attitude of the adults at the school. That it’s normal to talk things out, comment on them and that it’s great to give each other constructive feedback.(Teacher 5)

It was always nice when a teacher is willing to develop. Exploring and learning new things, those were usually more open to cooperation.(School psychologist 9)

Of importance are also the psychologist’s depth of knowledge and their ability to intervene. The ability to know how to deal with certain situations and offer solutions.(Teacher 4)

What matters is whether the psychologist wants to fit in, whether they hang out with the people and actively seek out contact or the kids, whether they’re interested. I feel like if I were to just sit in an office, nobody would notice me, nobody would even know I’m here and teachers wouldn’t come on their own, either.(School psychologist 7)

There could be a problem if the psychologist started giving advice. Our psychologist is more of the listening and asking kind. Sort of a mentor or coach approach. But if she were too intense and started giving too much advice, it would bother the teachers who have a specific idea of how things should be done, so it wouldn’t work. So yeah, she can give advice, but she needs to find the right amount.(Teacher 1)

The management put the psychologist on a certain level. As in, not above the teaching staff, but on the level of a teaching staff member and the management. They include them—not that just someone from the outside comes in to give advice, but that they’re a member and they participate in everything, including the decision-making process of the board of teachers. That is how the position of the school psychologist is set. How they manage to retain it, that’s up to them. But the way in which the management approaches it initially and introduces the psychologist is important.(School psychologist 6)

The school has a long-term issue and then they think that the psychologist can just show up, cast a spell and sort it out. But that’s not how it works.(School psychologist 1)

5. Discussion

Limitations

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

- (1)

- Recommendations for teachers

- (2)

- Recommendations for school psychologists

- (3)

- Recommendations for school management

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Štech, S.; Zapletalová, J. Úvod Do Školní Psychologie; Portál: Prague, Czech Republic, 2013.

- Chrtková, M. Školní Poradenské Pracoviště—Realita a Očekávání. Master’s Thesis, Univerzita Karlova, Prague, Czech Republic, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Finková, P. Školní Psycholog Očima Učitelů Základní Školy. Master’s Thesis, Univerzita Karlova, Prague, Czech Republic, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Stejskalová, J. Školní Psycholog a Jeho Práce z Pohledu Pedagogů. Master’s Thesis, Univerzita Palackého, Olomouc, Czech Republic, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Majdyšová, M. Pozice Školního Psychologa ve Vztahových Rámcích Školy—Z Pohledu Školního Psychologa a Učitele. Master’s Thesis, Masarykova Univerzita, Brno, Czech Republic, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pechová, M. Vliv Vztahů Na Pracovišti Na Profesní Identitu Školního Psychologa. Diploma Thesis, Karlova Univerzita, Prague, Czech Republic, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sakmárová, B. Spolupráca Školských Psychológov a Učiteľských Tímov z Pohľadu Školských Psychológov. Master’s Thesis, Karlova Univerzita, Prague, Czech Republic, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kultová, M. Vnímání Role Školního Psychologa Pedagogickými Pracovníky. Master’s Thesis, Univerzita Hradec Králové, Hradec Králové, Czech Republic, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Suchardová, L. Důvěra ve Vztazích Mezi Učiteli a Začínajícím Školním Psychologem. Master’s Thesis, Karlova Univerzita, Prague, Czech Republic, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ahtola, A.; Kiiski-Mäki, H. What Do Schools Need? School Professionals’ Perceptions of School Psychology. Int. J. Sch. Educ. Psychol. 2014, 2, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutkin, T.B.; Conoley, J.C. Reconceptualizing School Psychology from a Service Delivery Perspective: Implications for Practice, Training, and Research. J. Sch. Psychol. 1990, 28, 203–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conoley, J.C.; Powers, K.; Gutkin, T.B. How Is School Psychology Doing: Why Hasn’t School Psychology Realized Its Promise? Sch. Psychol. 2020, 35, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cason, E.B. Some Suggestions on the Interaction between the School Psychologist and the Classroom Teacher. J. Consult. Psychol. 1945, 9, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handler, L.; Gerston, A.; Handler, B. Suggestions for Improved Psychologist-teacher Communication. Psychol. Sch. 1965, 2, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reger, R. The School Psychologist and the Teacher: Effective Professional Relationships. J. Sch. Psychol. 1964, 3, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smilansky, J. Problem Areas in the Relationship of School Psychologists and Teachers. Sch. Psychol. Int. 1982, 3, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, S.M.B.; Howes, A.J.; Farrell, P. Tensions and Dilemmas as Drivers for Change in an Analysis of Joint Working Between Teachers and Educational Psychologists. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2008, 29, 400–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burden, R.L. Stress and the School Psychologist. Sch. Psychol. Int. 1988, 9, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikas, E. School Psychology in Estonia. Sch. Psychol. Int. 1999, 20, 352–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mägi, K.; Kikas, E. School Psychologists’ Role in School. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2009, 30, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Ni, H.; Ding, Y.; Yi, C. Chinese Teachers’ Perceptions of the Roles and Functions of School Psychological Service Providers in Beijing. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2014, 36, 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, R.S. A Comparison of Preservice and Experienced Teachers’ Perceptions of the School Psychologist. J. Sch. Psychol. 1980, 18, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, M.W.; Crosby, E.G.; Pearson, J.L. Role of the School Psychologist. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2001, 22, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimakos, I.C. The Attitudes of Greek Teachers and Trainee Teachers Towards the Development of School Psychological and Counselling Services. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2006, 27, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.J.K.; Klassen, R.M.; Georgiou, G.K. Inclusion in Australia. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2007, 28, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahtola, A.; Niemi, P. Does It Work in Finland? School Psychological Services within a Successful System of Basic Education. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2013, 35, 136–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolopoulou, A.K.; Oakland, T. School Psychology in Greece. Sch. Psychol. Int. 1990, 11, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, P.; Jimerson, S.R.; Kalambouka, A.; Benoit, J. Teachers’ Perceptions of School Psychologists in Different Countries. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2005, 26, 525–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topping, K.J.; Freeman, A.G. What Do You Expect of an Educational Psychologist? AEP J. 1976, 4, 4–9. [Google Scholar]

- Watts, P.E.; Pasternicki, G. Consumer Expectations of Psychological Service Delivery in an English Local Education Authority. Sch. Psychol. Int. 1988, 9, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-González, F.; García-Ros, R.; Gómez-Artiga, A. A Survey of Teacher Perceptions of the School Psychologist‘s Skills in the Consultation Process. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2004, 25, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavenská, V.; Smékalová, E.; Šmahaj, J. School Psychology in the Czech Republic: Development, Status and Practice. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2013, 34, 556–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štech, S.; Zapletalová, J. Kvalitativní Analýza Přístupu Školních Psychologů k Profesi—Srovnání Kazuistických Studií. In Metodika Práce Školních Psychologů na ZŠ a SŠ; Zapletalová, J., Ed.; IPPP: Prague, Czech Republic, 2001; pp. 37–47. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.; Strauss, A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory; Aldine: Chicago, IL, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Grounded Theory in Practice; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G. Theoretical Sensitivity: Advances in the Methodology of Grounded Theory; Sociology Press: Mill Valley, CA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, A.; Charmaz, K. The SAGE Handbook of Grounded Theory; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bartoňová, A.; Smetáčková, I. Učitelské Vyhoření v Perspektivě Školních Psychologů. E-Psychol. 2020, 14, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, K.E.; Erchul, W.P.; Raven, B.H. The Likelihood of Use of Social Power Strategies by School Psychologists When Consulting with Teachers. J. Educ. Psychol. Consult. 2008, 18, 101–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schowengerdt, R.V.; Fine, M.J.; Poggio, J.P. An Examination of Some Bases of Teacher Satisfaction with School Psychological Services. Psychol. Sch. 1976, 13, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.N.; Grossman, P.; Barker, D. Teachers’ Expectancies, Participation in Consultation, and Perceptions of Consultant Helpfulness. Sch. Psychol. Q. 1990, 5, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponec, D.; Brock, B. Relationships among Elementary School Counselors and Principals: A Unique Bond. Prof. Sch. Couns. 2000, 3, 208–217. [Google Scholar]

| Favorable Characteristics of the Teacher | Unfavorable Characteristics of the Teacher | Number of Mentions (n = 18) |

|---|---|---|

| Interest in students’ psyche and the class | Lack of interest in students’ psyche and the class | 13 |

| Openness to new things and the desire to develop | Rigidity and laziness | 17 |

| Cooperation and communication | Isolation and poor communication | 13 |

| Healthy self-confidence and self-reflection | Issues with self-confidence and self-reflection | 15 |

| Impartial to psychologists | Prejudiced against psychologists | 13 |

| Favorable characteristics of the SP | Unfavorable characteristics of the SP | |

| Professional competence | Professional insufficiency | 13 |

| Confidentiality | Violation of confidentiality | 12 |

| Finding a common solution with the teacher | Prioritizing opinion at the expense of the teacher | 15 |

| Communication and cooperation with colleagues | Poor communication and cooperation with colleagues | 15 |

| Impartiality | Breach of impartiality | 5 |

| Proactivity, helpfulness, interest | Passivity, not being accommodating, disinterest | 13 |

| Pleasant appearance and manners | Unpleasant behavior, repulsiveness | 14 |

| Knowledge of the school environment and pedagogy | Lack of knowledge of the school environment and pedagogy | 6 |

| Favorable school management | Unfavorable school management | |

| Democratic leadership of employees | Liberal or authoritarian leadership of employees | 9 |

| Creates favorable conditions for SP | Creates unfavorable conditions for SP | 18 |

| Favorable school focus | Unfavorable school focus | |

| Cooperation and open communication among employees | Isolation and insufficient communication among employees | 15 |

| Cultivating informal relationships in the workplace | Lack of interest in informal relationships in the workplace | 13 |

| Interest in the psyche and relationships of students | Focus mainly on teaching and student performance | 14 |

| The role of the SP makes sense to teachers | The role of the SP does not make sense to teachers | |

| Understanding the competencies of SP | Not understanding the competencies of SP | 15 |

| Realistic expectations about the possibilities of psychological work | Unrealistic expectations about the possibilities of psychological work | 15 |

| Other positive effects | Other negative effects | |

| Personal sympathy towards SP | Personal antipathy towards SP | 17 |

| Shared opinions with SP | Different opinions from SP | 10 |

| Older and experienced SP | Young and inexperienced SP | 12 |

| Supporting third parties (parents, students, other teacher, SCO, SCF) | Disrupting third parties (parents, students, other teachers, SCO, SCF) | 14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Müllerová, Z.; Šmahaj, J. Prerequisites of Good Cooperation between Teachers and School Psychologists: A Qualitative Analysis. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 1078. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13111078

Müllerová Z, Šmahaj J. Prerequisites of Good Cooperation between Teachers and School Psychologists: A Qualitative Analysis. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(11):1078. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13111078

Chicago/Turabian StyleMüllerová, Zuzana, and Jan Šmahaj. 2023. "Prerequisites of Good Cooperation between Teachers and School Psychologists: A Qualitative Analysis" Education Sciences 13, no. 11: 1078. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13111078

APA StyleMüllerová, Z., & Šmahaj, J. (2023). Prerequisites of Good Cooperation between Teachers and School Psychologists: A Qualitative Analysis. Education Sciences, 13(11), 1078. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13111078