1. Introduction

In the context of the ongoing societal shift towards a knowledge-driven paradigm, universities are undergoing a profound transformation in their approach to advanced doctoral education. This transformation has become particularly pronounced in the 21st century, and has led to a departure from the conventional model of doctoral education, which primarily revolves around the student–supervisor relationship. Instead, it has given rise to a strategic perspective on doctoral education, recognising it as an essential resource for addressing the multifaceted challenges presented by our technologically advanced society [

1].

Building upon this perspective, and acknowledging the pivotal role of post-graduate studies in advancing knowledge and its practical applications across diverse domains [

2], it becomes imperative to gain insight into the nature of doctoral research. This understanding is vital in assessing its contribution to fostering innovation and knowledge generation, especially in light of the profound impact of digital technologies across various sectors and institutions in society [

3,

4,

5].

Our study is positioned within this context, focusing on doctoral research conducted within Portuguese universities, specifically within the area of education, with a narrower emphasis on technologies in education (TE). Over the past three decades, TE has experienced rapid growth, prompting significant efforts to integrate digital information and communication technologies into educational and training contexts [

6].

TE, drawing on a diverse range of disciplinary sources that have evolved in response to technological advances, notably marked by the advent of personal computers [

7], has emerged as a prominent research domain. It seeks to comprehensively explore the potential of digital technologies, aiming to enhance the entire educational process, as well as students’ learning experiences and outcomes [

6,

8,

9].

While certain technologies are still in the process of establishing their presence in educational research [

10,

11], TE has evolved into a significant sub-field within the broader domain of education [

8]. A deeper exploration of this sub-field is essential for understanding its subject matter and the prevailing directions in scientific inquiry [

5,

7]. Research trend analysis is of particular significance. It not only aids in identifying and documenting shifts over time but also guides future research directions, which is particularly valuable for emerging researchers. This guidance helps to avoid redundancy and encourages the exploration of emerging areas [

12,

13,

14], innovative methodologies [

15], and alternative approaches to presenting research findings [

16].

In summary, the study proposed here is justified, first and foremost, by the lack of an existing comprehensive and in-depth analysis specifically focused on doctoral dissertations in the field of TE. It offers a unique opportunity to consolidate and critically evaluate the existing knowledge base within the context of doctoral research in Portugal. Secondly, due to the rapidly evolving nature of TE, with new trends, tools, and technologies constantly emerging, this study provides an updated overview of the doctoral research conducted in this country. This updated perspective is crucial for informing future educational practices. Indeed, understanding the current landscape of doctoral dissertations in TE can have significant implications not only for pedagogical practices but also for educational policies. Through the identification of gaps or trends, the results can guide decision-makers in the education sector and, particularly, at universities, in conducting doctoral studies. Lastly, by examining the specific context of Portugal, this study may uncover unique challenges, solutions, or insights that are not well represented in the existing literature, thus enriching the global discourse on TE research.

Given the breadth of this study, we adopt the definition of TE proposed by Canan et al., who define it as “as a complex and integrated systems process containing method, technique, and assistance to realise the learning-teaching functions in a quality way, putting into practice various methods, tools, and materials to enable individuals to learn at the highest level and seeking answers to the questions of “what” and “how should we teach” in the process of designing and learning-teaching environments” [

17] (p. 287).

From this standpoint, TE constitutes a field of study dedicated to investigating how instructional and learning processes can harness the capabilities of technology at various stages. Initially, this involves extending or substituting traditional teaching methods with digital tools. Subsequently, the focus shifts towards leveraging technology to promote student autonomy in constructing knowledge [

18,

19,

20,

21]. Additionally, TE encompasses educational resource development, the design and management of physical and virtual learning spaces, and the preparation of educators [

22].

The evolution of TE has been influenced by contributions from various disciplines related to education, such as psychology, communication, management, and pedagogy, adapting to the emergence of new technologies over time [

23]. These technologies range from analogue materials to personal computers, multimedia resources, digital networks, and artificial intelligence, including mass media like radio, cinema, and television. While analogue tools remain relevant, the prevalence of computers and digital technologies has surged, garnering increased attention from researchers [

24].

The 21st century, characterised by widespread internet access, rapid technological advancements, and new opportunities for schools and educators, has ushered in new research possibilities. These encompass the design, development, intervention, and evaluation of diverse pedagogical experiences and their impact on student performance [

25,

26]. Notably, there has been a significant surge in the study of technology integration for educational purposes, as evidenced by a threefold increase in TE publications between 2011 and 2018 [

6].

The state of the art. In the current century, driven prominently by widespread Internet access and swift technological advancements in the digital realm, along with the novel possibilities bestowed upon educational institutions and educators, fresh realms of investigation and prospective vistas have unfolded for researchers. These realms encompass not only the conception and advancement of pedagogical strategies but also the execution and assessment of distinct educational experiences, gauging their influence on student achievements [

5,

25]. Additionally, there has been a substantial upsurge in the scrutiny of matters linked to the integration of technologies for educational pursuits. As noted by Dubé and Wen, this growth is evidenced by a substantial escalation in the number of TE-related publications between 2011 and 2018, a surge of approximately 300% across this timeframe [

6].

Regarding the evolution of research themes and topics, there has been a growing inclination towards studies that scrutinise the educational potential of digital technologies in the context of online education and training. As pointed out by An, this inclination envelops not only purely online approaches but also hybrid methodologies [

25]. Furthermore, inquiries have extended to encompass the formulation of online learning resources, along with the establishment, administration, and assessment of systems that facilitate interpersonal communication among students and between students and teachers. An’s observations highlight that, in the 21st century, the research focus has been notably shifting towards areas such as social networks, mobile devices, the cultivation and progression of learning communities, and the exploration of informal learning pathways enabled by web access. This also encompasses the exploration of initiatives like open educational resources (OERs), mass open online courses (MOOCs), virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), gamification, and digital game-based learning.

Following a similar trajectory, this pattern is discernible in the pioneering work of Martin et al., who based their insights on the Horizon reports detailing influential technologies in school settings spanning from 2004 to 2010 [

26], as well as the investigations conducted by Dubé and Wen, which encompassed the period from 2011 to 2017 [

6]. In the former study, the researchers identified seven clusters in order of impact, ranging from the social web to augmented reality. The intervening categories encompassed mobile devices, games, the semantic web, man–computer interaction, and learning objects. The latter study by Dubé and Wen employed a parallel methodology and highlighted six trends, again in order of impact: mobile devices, games, learning analytics, simulation technologies, maker technologies, and artificial intelligence [

6]. When comparing these two studies, the authors underscore the sustained prominence of mobile technologies and games, alongside the emergence of learning analytics and artificial intelligence [

6].

Furthermore, the recent scholarly curiosity towards emergent technologies like artificial intelligence, virtual reality, and augmented reality is underscored by Kimmons et al. In their scrutiny of a corpus exceeding two thousand articles from scientific journals within the field of TE, published in 2021, these terms recurrently surfaced within the scientific literature [

27]. By examining keyword frequencies in these studies, encompassing phrases comprised of two words, the authors elucidate that computational thinking and learning environments stand as the most frequently referenced subjects.

Although less numerous, the examinations of doctoral dissertations within the TE domain conducted in various countries can serve as pertinent sources of information. These analyses aid in recognising and tracking the evolution of research interests and topics across diverse geographical and academic settings, alluding to consistent trends that align with those outlined here [

28].

This phenomenon is evident, as exemplified by the research conducted by Durak et al., who aimed to scrutinise dissertations completed in the domain of TE in Turkey up to 2018 [

29]. Through their investigation, encompassing a total of 137 theses, including master’s dissertations, they discovered that online learning holds the foremost position as the most prevalent subject. This is closely followed by the broader domain of information and communication technologies, teacher training, and special education. With regard to areas of specialisation, the same study elucidates a marked prevalence of dissertations focused on education and training (80.6%), in contrast to fields associated with sciences and technology or computing sciences, which were notably less represented. Theoretical underpinnings were also explored, with nearly half of the scrutinised dissertations anchored in at least one theoretical framework. The most cited theoretical foundations encompass multimedia learning theories, constructivist theories, and notably, the technology acceptance model (TAM). The authors highlight that many of these dissertations did not cite any theories or specific theoretical framework [

29].

In a separate study conducted in Turkey, Kara and Can examined 705 theses, concluding that the most prevalent research focus was on learning environments. This theme constituted the subject of inquiry in roughly one third of the examined theses. However, an observed decline in recent years is noted within the analysed time frame (1996–2016) [

30]. A parallel diminishing trend is also discernible in topics related to pedagogy, learning/instruction/teaching theory, and assessment. Conversely, subjects like emerging technologies and the acceptance thereof, as well as teacher/trainer and learning themes, demonstrated an upward trajectory. This trend was particularly prominent in the latter years of the analysed period [

30].

Also in Turkey, an inquiry into the trajectory of subject matters in 292 doctoral dissertations completed from 2011 to 2020 was undertaken by Gunduz et al. In their results, notably, they underscore an amplified interest in educational/3D games, particularly evident within the timeframe of 2015–2020 [

7]. The researchers attribute this inclination mainly to the advancement of graphical technology. Consequently, the exploration of the ramifications of employing virtual reality within educational settings, especially regarding its entertainment aspect, becomes a central focus. The investigation specifically hones in on the potential of these strategies to kindle students’ motivation for learning [

7].

Conducted in Pakistan, another investigation undertaken by Asdaque and Rizvi aimed to depict the landscape of research concerning online education within the context of Allama Iqbal Open University’s doctoral program. This study spanned the period between 2001 and 2014 and was based on an examination of 37 theses. Their findings highlighted that the most prevalent subjects were centred around course design (instructional design), student support services, student characteristics, and the professional development of teaching staff [

31]. However, the authors bring to light an inherent asymmetry in the topics under exploration. They argue that a collection of crucial research domains related to online education do not attract comparable attention from Ph.D. scholars. Specifically, they emphasise aspects concerning quality assurance, management, and the evolution of research methodologies within online education as areas warranting increased investigation [

31].

In the context of Portugal, a meta-analysis conducted by Coutinho and Gomes pertained to research within the Master’s Program in Educational Technology at the University of Minho. This examination encompassed 60 master’s dissertations finalised between 1995 and 2005. The analysis revealed that the predominant research subjects revolved around resources, methodologies, strategies, and pedagogical techniques facilitated by information and communication technology systems. These encompassed domains like hypermedia, audiovisual/video materials, multimedia and educational software, imagery, the Internet and the World Wide Web, and e-learning and online education, as well as virtual learning environments [

32].

The examination of technologies emerges as a primary focus within the study, as demonstrated in the analysis of 226 master’s theses finalised between 1986 and 2005. This inquiry, conducted by Costa, underscores the prominence of technologies as both subjects of scrutiny (for instance, evaluating educational software) and objects of development. In this regard, studies centred on the creation and enhancement of innovative pedagogical and didactic resources come to the fore [

33]. Costa’s analysis further notes the emergence of subjects within the pedagogical domain that are more directly interwoven with the integration of digital technologies. This includes their application in teacher training, as well as within educational institutions and the broader teaching and learning milieu [

33].

In our examination of the literature review as a whole, the pursuit of comprehending this phenomenon surfaces as a central aspect. It becomes evident that this phenomenon is markedly intricate and wide-ranging, surpassing the narrower technological focus. Although a substantial portion of the studies aimed to assess or validate the viability of the prevailing technology as a method or solution for addressing historical issues associated with traditional school-based learning built around a prescriptive curriculum [

34], this evolving trajectory prompts a reconsideration of the objectives and intentions of the research within this domain. This shift amplifies the longstanding belief that it is necessary to highlight how technologies become integrated within diverse educational contexts. This shift, furthermore, fosters an inclination towards embracing the influence of other knowledge domains, and thereby fostering interdisciplinary perspectives. This inclination prompts those in related fields of study to investigate topics traditionally confined to researchers with technology backgrounds [

35,

36].

Research questions. Taking into consideration these reflections, and over the three decades since the introduction of digital technologies in Portuguese education and the first TE-specific Ph.Ds. [

15], our study endeavours to initiate a series of projects aimed at identifying, mapping, and scrutinising the scientific research conducted within Portuguese universities. With a specific focus on the doctoral level, this paper delves into three core dimensions of analysis for characterising doctoral research within the domain of TE at Portuguese universities. These dimensions encompass Authors and Dissertations, Issues Studied, and University Contexts. Each dimension is explored through a set of interconnected research questions, shedding light on the authors, themes, topics, technologies, and contextual aspects of these dissertations, as described below:

Authors and Dissertations: RQ1.1. What is the nationality of the authors of the dissertations? RQ1.2. What is the gender of the authors? RQ1.3. How has the number of dissertations evolved over a span of 25 years (1997–2022)?

Issues Studied: RQ2.1. What are the predominant themes addressed within the dissertations? RQ2.2. Which specific topics emerge under these themes? RQ2.3. What drives the selection of research problems? RQ2.4. What is the main purpose of the studies carried out? RQ2.5. Which educational technologies and tools are the primary subjects of investigation? RQ2.6. What theoretical frameworks serve as the foundation for the studies?

University Contexts: RQ3.1. Which institutions provide the academic settings for the investigated dissertations? RQ3.2. Which specific Ph.D. courses and specialties do these dissertations align with? RQ3.3. Which supervision models are most commonly used in the research process?

Through this inquiry, we strive to provide a comprehensive understanding of the landscape of doctoral research within the realm of TE in Portuguese universities. By addressing these dimensions, our study contributes to the advancement of scholarship by offering a nuanced perspective on the evolving intersections between technology, education, and research. This investigation not only enriches academic discourse but also provides valuable insights for educational practitioners, policymakers, and stakeholders seeking to harness the potential of technology to enhance learning outcomes and shape the future of education.

Therefore, before presenting the results in detail, we describe the methodology and procedures adopted to collect and analyse the empirical data supporting this study.

4. Discussion

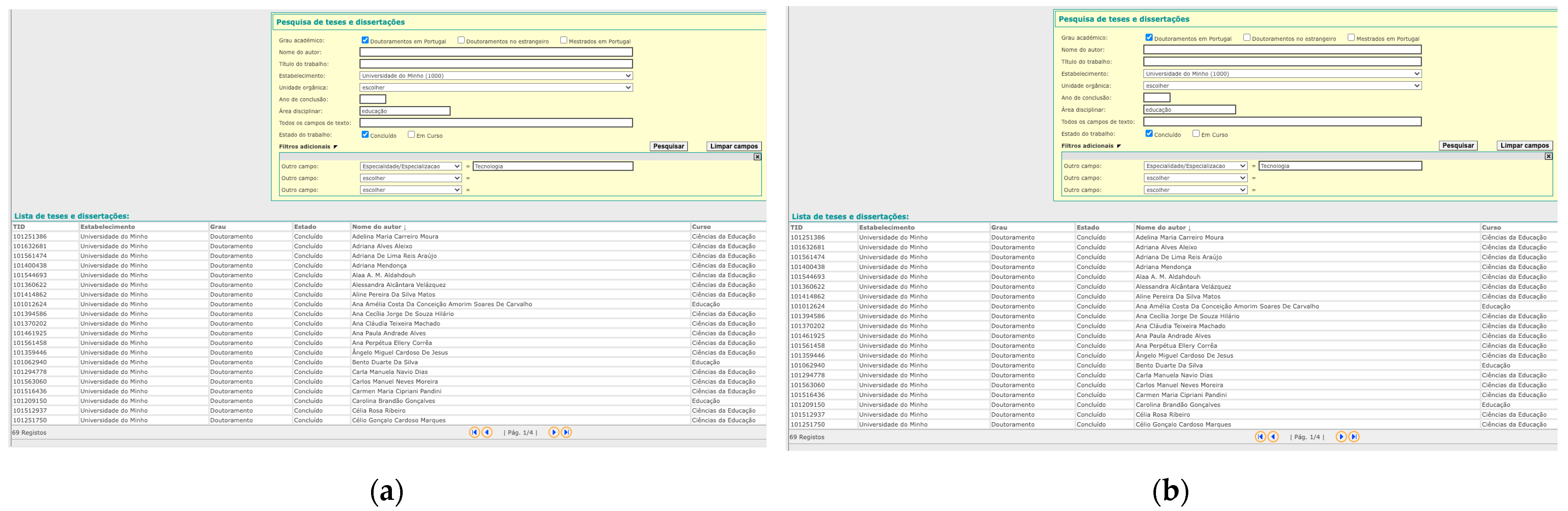

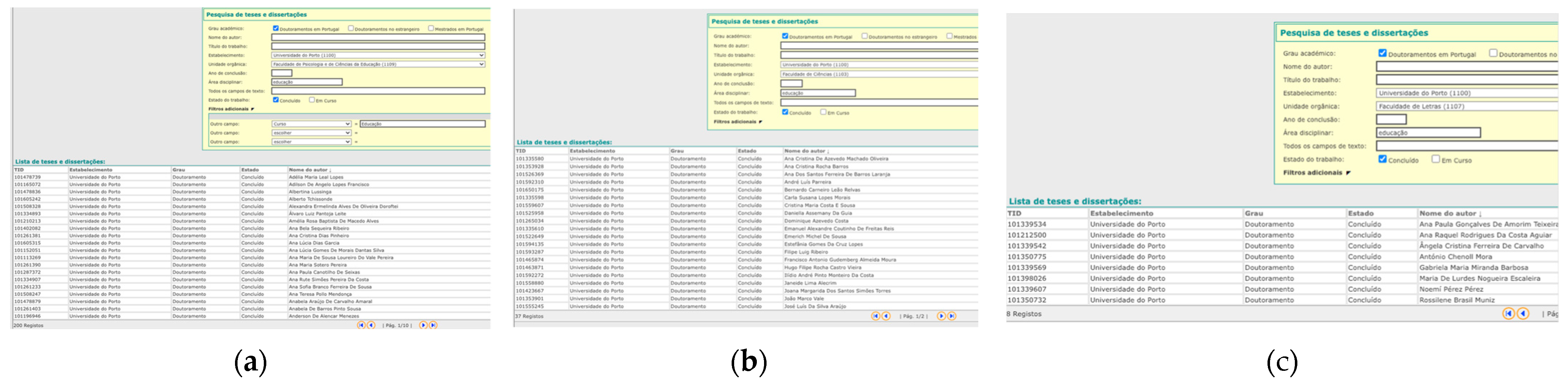

In this study, we sought to analyse all the Ph.D. dissertations produced in Portugal in the scientific area of Education that focused on TE. As a pioneering research project in our country, we deliberately opted not to establish any cutoff time, deciding that all dissertations registered by the end of 2022 that met the selection criteria, defined throughout the process to compile the corpus of the analysis, would be included. Therefore, based on a total of 380 doctoral dissertations produced in the field of TE between 1997 and 2022, this study is the first of a series of projects we intend to carry out to deepen the understanding of the panorama related to the evolution of the research in the field of TE. This work aims to provide a broad and sufficiently detailed picture of a set of variables that we have broken down into three dimensions of analysis: the authors and dates of the dissertations, the issues studied, and the university contexts.

With regard to the first dimension, referring to the authors and dates of the dissertations, we found that, despite the prevalence of Portuguese authors, as was to be expected, a large proportion of the scientific-academic production carried out in the Portuguese universities—around one third—is undertaken by international students, almost all of whom come from Portuguese-speaking countries, with Brazil by far the most represented country. This finding, as well as probably reflecting the impact of the marketing strategies implemented by Portuguese universities in recent years to attract new students, also highlights the emergence of an internationalisation component in the scientific production in TE, which is likely to continue in the future, as can be deduced from the knowledge produced in the universities themselves regarding the profiles of the students who apply to Portuguese higher education institutions.

While this topic is not given much emphasis in the literature reviewed, we believe that this international component will certainly lead to a wider diversity of questions, issues, motivations, interests, and reference frameworks that will naturally be reflected in the research in TE and, therefore, justifies an autonomous analysis approach in future work.

With respect to the first dimension, there is a noticeable gender gap between the authors of education Ph.Ds., with a clear preponderance of female authors. This finding, which illustrates women’s willingness to carry out advanced studies, when compared with the results available in the literature that show the predominance of the male gender in the scientific production in TE in Portugal and elsewhere [

28,

36], seems to indicate that the willingness of women to carry out advanced studies is not borne out, subsequently, in the sharing and dissemination of the knowledge produced during the Ph.D. courses, namely through the publication of scientific articles.

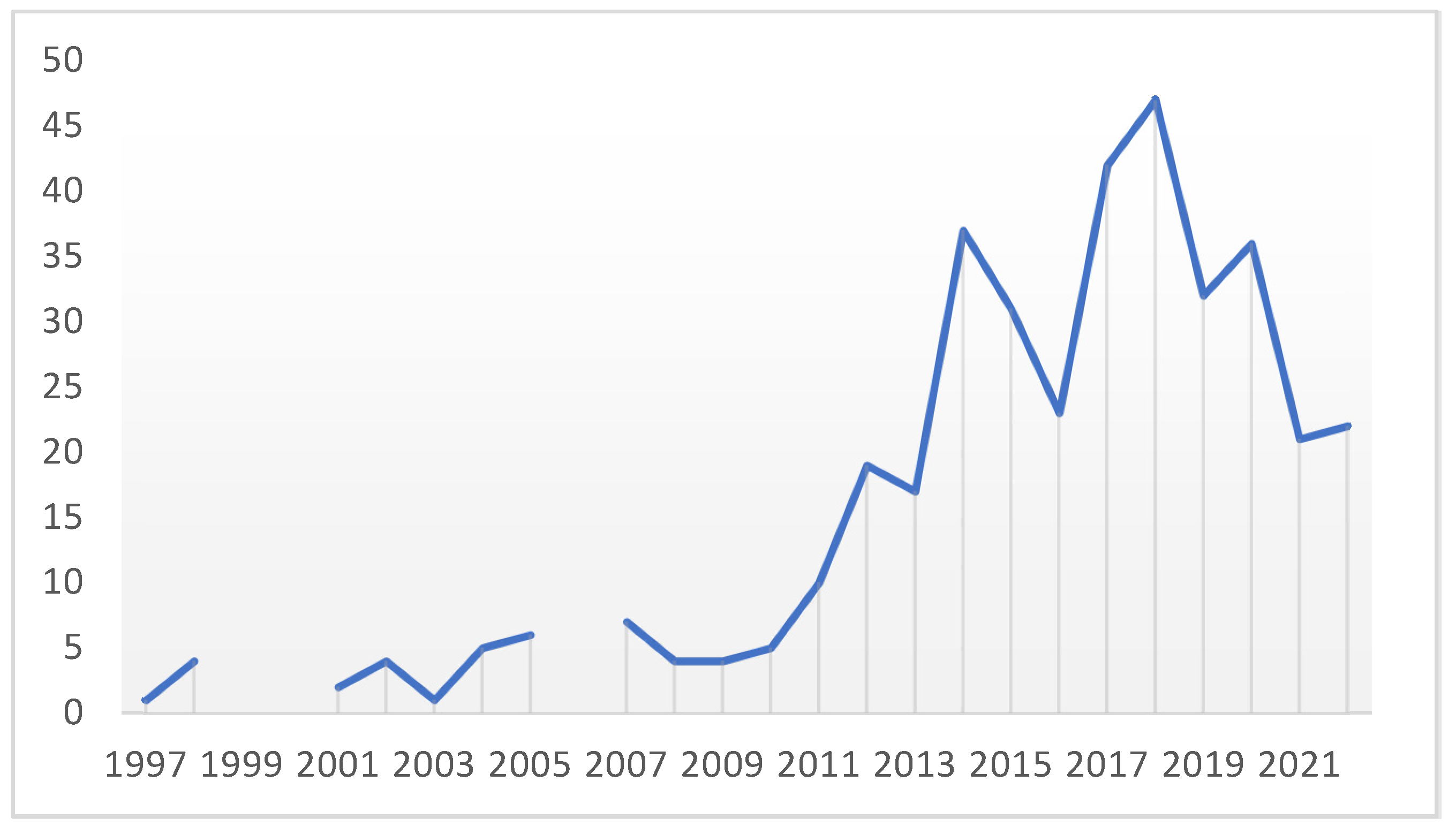

Finally, by examining the evolution of the number of dissertations produced per year, we find that the first decade (1997–2007) mirrored a process whereby the research into TE started to affirm itself, albeit with a degree of instability, with a very slight upward trend in the number of dissertations and a few interruptions to this trend. It is pointed out that only from 2010 onwards was there a significant expansion in the scientific production of the studies under analysis, culminating in the highest number of dissertations in 2018. As a whole, the growth in the number of works recorded from 2010 onwards confirms what other bibliographical reviews had found in the field of TE in general [

6,

7,

28].

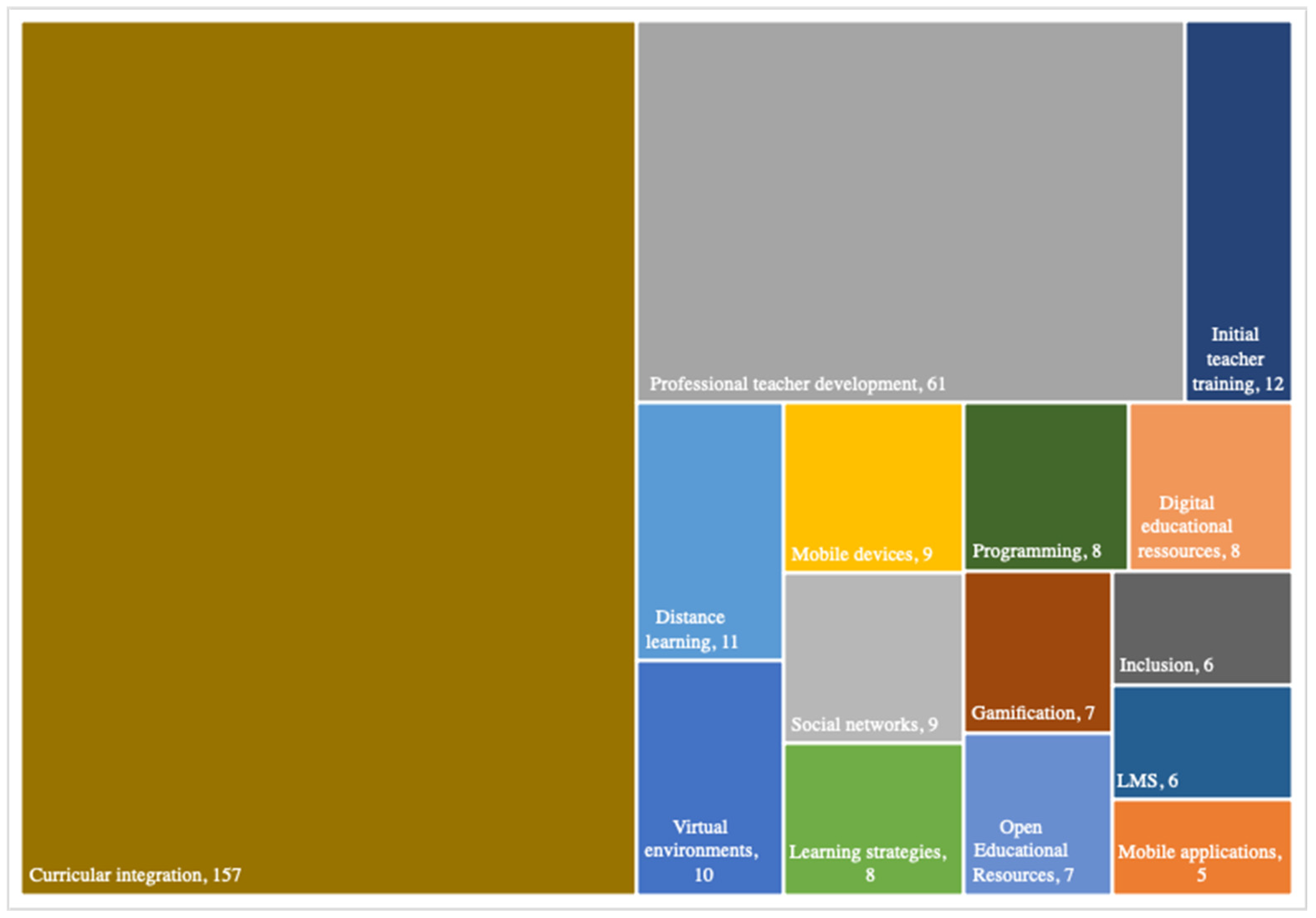

In relation to the second dimension, relative to the issues studied, and as we pointed out earlier, we have taken as our reference point a diversified set of aspects aimed at characterising and deepening knowledge about the academic research carried out in the third study cycle. The idea was that an articulated analysis of these different aspects would provide an overview of what is being studied, helping us understand to what extent this research, as we wrote in the Introduction, can boost the capacity for innovation in the search for solutions to the challenges raised by the use of digital technologies and how to consolidate and lay the groundwork for changes in educational practices.

Along these lines, it is important to point out right away that the findings do not allow us to conclude that the research undertaken in TE for Ph.D. courses in Portugal focuses mainly on experimentation on and/or analysis of the potential of emerging technologies. Despite the fast changes and the rise in the rate of technological innovation in different sectors that also have an impact on educational practices [

6], in our study, it is especially noteworthy how many dissertations tackle topics related to the “Teaching and Learning” process itself, in which digital technologies are explored regarding concerns of a curricular nature (literacy, teaching and learning with technologies strategies, digital assessment, etc.).

We note, as observed on the international level, that most dissertations focus on problems and issues related more to the pedagogical and didactic aspect inherent to the infusion of technology in educational and training processes than to problems of a more technological nature (when the focus is on the technology, at least at first glance, it seems to constitute the end in itself). Alkraiji and Eidaroos, for example, note that, even in studies more geared towards the analysis of sociotechnical systems, with an emphasis on the interaction between people or organisations and technical innovation, concerns about pedagogical issues are much more pressing than questions of a technological nature [

28]. Likewise, the findings of the research conducted by Lai and Bower clearly highlight the focus on questions related to learning results, also showing the greater efficacy of pedagogical approaches that involve interaction, gamification, constructivism, learning centred on the student, and feedback [

12].

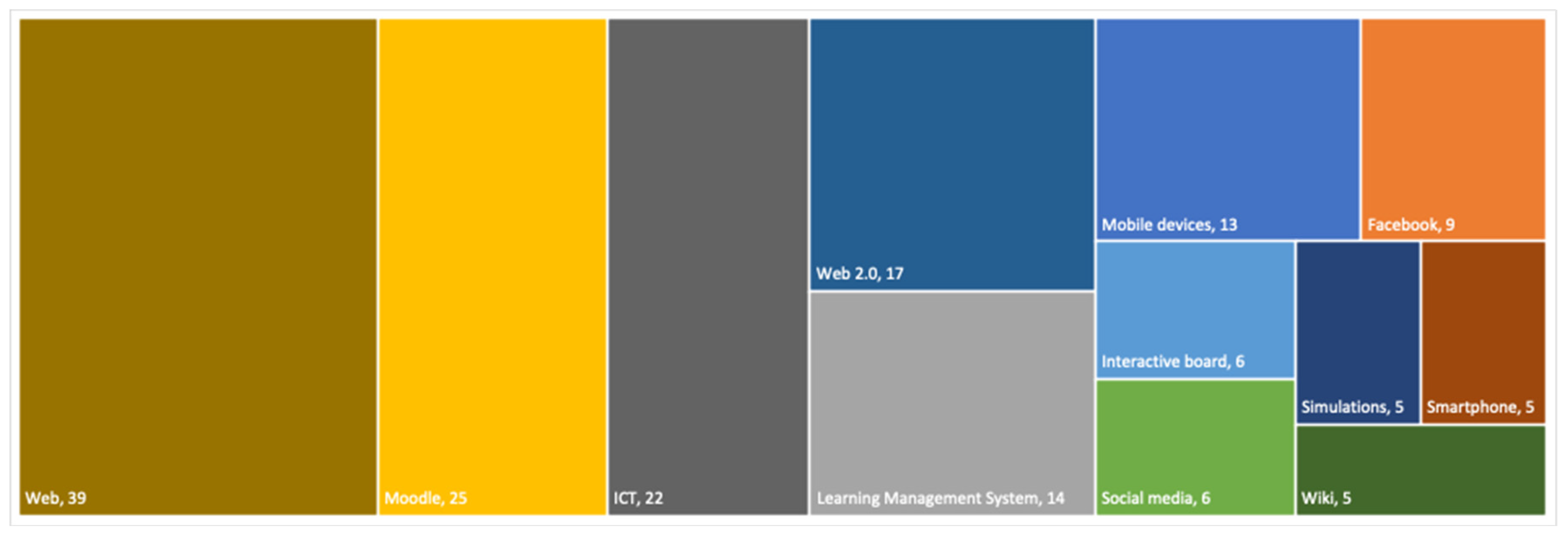

In our study, the reduced focus on the technological dimension is also demonstrated by the considerable number of dissertations that make no explicit reference to the tools (around a third of the

corpus analysed), and for those that place a more explicit emphasis on the tools, their references are concentrated in two categories, namely “Web and Social Networks” and “Online Learning Platforms and Environments”, suggesting a stronger approximation to the so-called short-term trends outlined in the Horizon Reports of 2011, 2013, and 2014 [

6].

In the light of international trends and forecasts, this focus on tools that do not reflect the most recent technologies may indicate the inability of the research to respond quickly enough to tackle the new practices, but it may also translate to an inflexion in the logic behind the idea of automated pedagogical practices encouraged by fascination about how (new) technologies impact our lives, which is well documented in the literature [

10].

Finally, another facet that must be highlighted within the scope of the issues studied is linked to the necessary reflection on the role of theory in the construction of knowledge in the field of TE. The findings of this study show that the more traditional theoretical bases that are deemed more important in the evolution of this area [

34] are not particularly evident. The theoretical foundations that are most frequent, but are far from having a significant presence, are anchored in references that allude to presuppositions and principles that underpin cognitivist and constructivist theories.

However, the most intriguing result of this study, which corroborates the results from other research [

15,

29,

33], is the absence of an explicit theoretical orientation. In our case, around one third of the dissertations did not seem to align themselves with any specific theory or theoretical reference point. A possible interpretation of these results, as pointed out by other studies in the field of TE [

15], may be related to a free and open spirit in the researchers, allowing them to forge new approaches (theoretical and methodological) that are often not limited to a strictly disciplinary point of view. This hypothesis seems equally relevant to helping us explain the emergence of a pattern that mirrors and, in a certain sense, validates the interdisciplinary nature of TE, which is shown both in the research [

11,

17] and in the post-graduation offers available [

4,

5].

With regard to the third dimension, focused on analysing and describing the institutional contexts in which the dissertations are carried out, the results show that public universities are clearly paving the way in knowledge production in the area of TE in Portugal. The University of Minho and the University of Aveiro play leading roles in advancing knowledge in this specific field, together accounting for almost half the dissertations carried out. The University of Lisbon and the Open University also play significant roles in the production of dissertations in this field, together contributing just over a quarter of the total number.

Several factors may help explain why these four institutions are so active in the research into TE in Portugal. In addition to their academic reputation in the area under analysis, they are institutions that have sought to establish a range of collaborations and partnerships to develop teaching and research projects, as well as having academic departments specialised in TE and/or research centres that attract researchers and scholarship students who are interested in this field.

With respect to the doctoral courses within which the research is carried out, we see that more than two thirds of the dissertations are for courses related to Education Sciences or Education. The University of Minho, the University of Lisbon, and the Open University are where almost half of the dissertations are produced, and also noteworthy is the Multimedia in Education course offered by the University of Aveiro, which accounts for around one sixth of the dissertations produced in TE.

The analysis carried out also enables different speciality areas to be identified, of which “Educational Technology” is the most common, followed by “Information and Communication Technologies in Education”. However, it should be pointed out that, in one third of the dissertations that comprise the

corpus of analysis of this study, no speciality area was explicitly mentioned. This finding, as well as being an indicator that reflects a research dynamic that transcends the logic of specialised knowledge in TE [

11,

17], also helps us to understand the difficulty felt in relation to categorising the dissertations by linking them to conceptual structures that traditionally characterise the specificity of the TE area.

In any event, as other studies have suggested, it is certainly a reflection of the changeable evolution and nature of the research areas, which can be viewed as an enrichment of the field, enabling the integration of wide-ranging perspectives and the emergence of new approaches [

19].

In this study, the emergence of new approaches also manifests itself clearly in the ways in which the dissertations are supervised. Despite the prevalence of the traditional supervision model, co-supervision comes to the fore as an increasingly adopted practice in the institutions where the dissertations are produced and, above all, in the universities that belong to the higher education public network. Although it is necessary to explore the factors that influence the choice between individual supervision and co-supervision in more depth, this finding seems to reflect a greater emphasis given to diversity in perspectives, experiences, knowledge, and support during the research process.

5. Conclusions

Based on the results and discussions, this section summarises the key contributions of this comprehensive study on doctoral research in TE. The conclusions are organised according to the three research dimensions outlined in this work: authors and dissertations, issues studied, and university contexts.

Authors and Dissertations: This investigation highlights the evolving landscape of TE research in Portugal. Notably, the internationalisation of this research field has become increasingly evident, with a growing number of contributions from foreign students, particularly those from Portuguese-speaking countries, such as Brazil. This phenomenon underscores the emergence of a diverse and globally informed research community in Portugal. Moreover, a striking observation is the pronounced gender disparity among authors, as female scholars have shown a strong commitment to advancing their expertise in TE. This departure from the global trend, where male authors typically dominate TE research, suggests that Portuguese women actively engage in advanced TE studies, contributing to a more balanced and inclusive research environment. Furthermore, our analysis of the temporal evolution of TE dissertations over a quarter of a century, from 1997 to 2022, underscores the field’s growth and maturation in Portugal. A significant upswing in the research output since 2010 signifies the expanding interest and commitment from researchers when it comes to exploring the multifaceted dimensions of TE, setting the stage for further advancements in the field.

Issues Studied: Delving into the thematic landscape of TE research, this study uncovered a diverse array of themes. Notably, “Teaching and Learning” and “Professional Development” have emerged as dominant areas of investigation. These thematic preferences signify a deliberate departure from a predominantly technology-orientated viewpoint, with an emerging emphasis on pedagogical aspects. Within the Portuguese research landscape, there is a growing trend of investigating the potential of technology to augment the educational process and, simultaneously, cater to the professional growth requirements of educators. Additionally, our findings reveal that researchers predominantly derive their research problems from real educational contexts. This practice demonstrates a commitment to bridging the gap between theory and practice and reflects the field’s practical relevance. Researchers are actively striving to enhance their comprehension of educational challenges and develop impactful interventions that can have a positive influence on the realms of teaching and learning.

University Contexts: In the context of universities in Portugal, this study recognises key institutions, such as the University of Minho and the University of Aveiro, as driving forces in the advancement of TE research. These institutions possess academic departments and research centres dedicated to TE and foster collaborations and partnerships that stimulate innovative teaching and research projects. The prevalence of co-supervision models in these institutions underscores their commitment to diverse perspectives, experiences, and collaborative support during the research process.

In conclusion, the emphasis on practical relevance, pedagogical considerations, and international collaboration not only enriches educational research in Portugal but also has significant implications for the global research landscape in education. These implications include the development of innovative research approaches and the strengthening of research networks in universities aimed at jointly addressing real-world issues in the field of education. In this regard, this research not only enriches academic discourse, but also provides valuable insights for education professionals, policymakers, and stakeholders seeking to harness the potential of technology to improve learning outcomes and shape the future of education.