Abstract

University of Surrey’s School of Veterinary Medicine introduced an assessment called On The Spot Presentation-based Assessment (OTSPA) into the 3rd and 4th year of a 5-year veterinary degree programme. The OTSPA is designed as a low-weightage summative assessment, conducted in a supportive learning environment to create a better learning experience. The OTSPA is a timed oral assessment with an ‘on the spot’ selection of taught topics, i.e., students prepare to be assessed on all topics but a subset is chosen on the day. The OTSPA was designed to test the students’ depth of knowledge while promoting skills like communication and public speaking. The aim of this study is to describe the design and operation of the OTSPA, to evaluate student perception of the approach, and to assess the OTSPA’s predictive value in relation to the final written summative assessment (FWSA), which is an indicator of academic performance. This study assessed the student perceptions (N = 98) and predictive value of the OTSPA on the FWSA in three modules: Zoological Medicine (ZM), Fundamentals of Veterinary Practice (FVP), and Veterinary Research and Evidence-based Veterinary Medicine (VREBVM). In the perception study, 79.6% of students felt that their preparation for OTSPAs drove an understanding and learning of topics that formed part of the module learning outcomes. Only a small group (21.4%) reported the assessment to be enjoyable; however, 54.1% saw value in it being an authentic assessment, reflecting real-life situations. The majority of students felt that the OTSPA helped with improving communication skills (80.4%). There was a small but significant positive correlation between the performance in OTSPAs and the FWSA in all modules. This suggests that OTSPAs can be useful in predicting the outcomes of the FWSA and, furthermore, could have utility in identifying where support may be helpful for students to improve academic performance. Outcomes from this study indicate that the OTSPA is an effective low stake summative assessment within the Surrey veterinary undergraduate programme.

1. Introduction

Effective and authentic assessments provide undergraduate veterinary students with the knowledge and skills to navigate themselves within the scientific community as well as clients who may not have the specialist understanding. Authenticity in an assessment is key to replicate ‘real-life’ learning that a veterinarian will face in clinical practice [1]. Assessments can be considered as formative and summative; (i) formative assessments drive learning through feedback and do not contribute towards the students’ final grade [2] but better prepare them for the graded (ii) summative assessments that are commonly referred to as high-stake examinations because of the grade contribution that reflects academic performance [3,4,5].

Summative assessments are used as the final graded outcome in undergraduate courses, representing the student’s ability to acquire knowledge and reflect ‘how much the student knows’ [6]. In health professions education (HPE), academic performance is used to decide if a candidate is suitable to progress to advanced training. This is in place to prevent incompetent practitioners from jeopardising the public’s health [7]. Evidently, a comprehensive and authentic assessment has a close association to clinical performance and plays a role in the student’s career progression [7]. Understandably, students tend to feel very stressed when taking these high-stake assessments because of the risk of failing the examination [5].

When considering the use of feedback from summative assessments, it is often perceived to come ‘a little too late’ for improvement on the academic performance of the student [8]. Conversely, formative assessments bridge that knowledge gap, aim to drive learning through feedback, and arguably act as a predictive tool to gauge student performance in summative assessments [3,4,9]. Therefore, learners have a lot to gain from attending formative assessments despite them not having a grade. Carrillo-de-la-Peña et al. (2009) found that participation in a formative assessment was the main factor that drove learning and an overall better academic performance in the summative assessment [10].

Although intrinsic motivation for learning will drive student engagement to participate in a gradeless assessment such as a formative assessment, it is often very subjective and can be influenced by factors like gender, subject area, and type of feedback [5]. Not all students will share the same motivation and this will likely contribute to a varied impact on overall graded academic performance. Gradeless assessments are known to create a more supportive environment for students and while it may increase participation, it does not address the ‘training for real life’. This poses the question—what would motivate a student to engage in an assessment that does not contribute to overall academic achievement?

Mogali et al. (2020) found that students opted for a graded assessment despite the stress they felt from it because it helped with learning and overall academic performance [5], suggesting that extrinsic motivation has an influence that drives student learning as they learn for the assessment. Recognising this, a combined approach of an ‘assessment for learning’ and ‘assessment of learning’ would likely have a good impact on student learning. This paper will evidence the need for a joint modality of a summative assessment with a formative assessment flavour [11] that drives learning through extrinsic motivation and a supportive approach commonly felt in a formative-style assessment. In addition, the assessment should provide the learner with transferable skills that are needed in future professional practice.

Further considerations when selecting the type of assessment to be used are its authenticity, contributing value, and ease of implementation. Oral assessments offer a deep understanding for the learner and are reported to be more useful than written assessments that encourage superficial understanding from the common ‘memorize and regurgitate’ approach [12]. However, an oral assessment can be complex and using it accurately requires assessing its fairness, validity, and reliability which adds further challenges to implementing it [13]. Critics of oral assessments often debate whether students simply memorise and recite material without true understanding [14], or genuinely gain a better knowledge of the material through active preparation [15,16,17]. However, the interactive nature of oral assessments allows examiners to gain further clarification and to test the understanding of the subject the students are presenting on [18]. By answering questions using their own words, there is less of an assumption that students simply memorise the material as clarifying points will demonstrate a thorough understanding of the topic [19]. An assessment using an ‘Open Structure’ gives examiners freedom to ask questions to test students’ understanding and adds value to making oral assessment somewhat resistant to plagiarism [20]. It is for these reasons that, despite the logistical burden of organising oral assessments and the stress associated with it, oral assessments are still widely used in clinical assessments within health professions education and postgraduate viva examinations [12,21,22].

An added benefit for students undergoing oral examinations is the ability to improve communication and presentation skills which is important not only for personal progression, but also from a career development perspective [16,23,24,25,26]. This is particularly important in the veterinary profession, where communication skills are recognised as a day-one competency by the professional registration body, the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons [27]. Veterinarians are expected to collate and condense a large depth of knowledge, efficiently communicate this information, and tailor presentations to the intended audience which can range from pet clients and colleagues during clinical rounds to a group of experts at a conference. Good presentation skills are crucial to keep the focus of the audience and lay out the information in a digestible manner. Outcomes from an international survey of veterinary practitioners based in the UK and USA reported a gap in communication competency and recommended a prioritisation of communication skills within the curriculum through teaching and assessments [28], many of which are graded assessments [29]. To learn how to communicate effectively is a dynamic skill and students should have a myriad of opportunities within the programme to be able to practise this. Communication skills within the curriculum should go beyond communication in a consulting room to widen the context in which it is taught and assessed [30]. Taking a ‘Decontextualised’ approach to drive the authenticity of an oral assessment means that communication skills can be practised and learnt outside the realms of clinical practice [20].

Separately, oral assessments are often associated with a great deal of stress especially for students who experience (i) disability affecting their speech [31,32]; (ii) Social Anxiety Disorder [33], or (iii) present using their second language [34]. Stress and anxiety can affect learning and the experience of life as a university student [33]. Despite this, there is evidence that students will choose a presentation-based assessment if it is beneficial to the learning process [35]. Realistically, it is challenging to avoid all forms of discrimination within assessments. Hazen (2020) reported students to have a stronger preference for oral assessments because they offered an opportunity to portray the extent of knowledge the students truly possess [31], as opposed to a written format, where structured questions limit the ability to demonstrate the range of knowledge. Written assessments can also be stressful for neurodiverse students struggling with writing performance [36]. The appropriate approach should not be avoiding the assessment but ensuring sufficient support is provided to increase the learners’ self-efficacy, a concept developed by Bandura (1993) where the learner develops a belief in their ability to perform a task by regulating their own learning [37]. Encouraging self-efficacy in an oral assessment through support by peers in a conducive learning environment would develop the learners’ confidence in oral presentations and nurture communication skills, in line with the ‘assessment for learning’ modality [38]. In a veterinary context, there is strong evidence that increased self-efficacy in veterinary students influences their ability to develop resilience, a valuable characteristic for employability [39]. An environment that supports peer learning is less likely to occur at a high-stake summative oral assessment compared to a formative assessment; however, due to the lack of extrinsic motivation in the latter, students’ participation may be low. Using a constructive alignment approach to a curriculum design will provide students with the opportunity to ‘construct’ their knowledge and align it to the intended learning outcomes, forming their own conducive learning environment [40].

The On The Spot Presentation-based Assessment (OTSPA) was developed at the University of Surrey’s School of Veterinary Medicine as an outcome-based assessment that promotes deep learning within a supportive learning environment. To achieve this, the assessment was made summative in order to drive learners extrinsically, but, at the same time, it was ‘low-stake’ due to its low weightage and performance in small groups to maintain a supportive learning environment.

Joughin (1998) identified six dimensions (‘Primary content type’, ‘Interaction’, ‘Authenticity’, ‘Structure’, ‘Examiners’, and ‘Orality’) of oral assessments which cover a range of practices that can be used to identify types of oral assessments that are suitable for assessing learning outcomes [20]. The OTSPA was not developed primarily to assess communication skills but that was an additional outcome of the assessment. Using the dimensions from Joughin (1998), the OTSPA’s concepts were mapped to ensure a structured approach (Table 1).

Table 1.

On The Spot Presentation-based Assessment (OTSPA) principles mapped to the dimensions and ranges of practices outlined by Joughin, G (1998).

The aim of the study was to assess the use of the OTSPA as a low-stake summative assessment that drives learning. This was achieved by evaluating student perceptions and assessing the predictive value that the OTSPA had on the high-stake final written summative assessment. A predictive relationship is useful in identifying students that require additional support.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. About OTSPA

The University of Surrey’s School of Veterinary Medicine introduced the On The Spot Presentation-based Assessment (OTSPA) within the undergraduate veterinary curriculum in 2017 in order to include an authentic low-stake summative assessment conducted in a supportive learning environment encouraging self-efficacy as well as contributing to the final grade at the end of the semester. The OTSPA is a timed oral assessment using topics aligned to the module learning outcomes; it is made available to students four weeks in advance to allow sufficient time for preparation. Prior to the assessment, all assessors receive training via online sessions, videos, and documents to ensure consistency. It is not designed as a group assessment; however, students are encouraged to revise and practice as a group to mimic how it might feel on the day of the assessment where peer questioning was encouraged.

Students are assigned in small groups and perform individual oral presentations to their assessors and peers. On the day of the presentation, each student selects a number that will randomly allocate a topic. This represents the ‘on the spot’ element of the assessment where the student will have one minute preparation time to allow the recall of knowledge, a skill needed to deliver information to clients in a time-constrained, often highly stressful situation. This element of uncertainty accurately represents real-life situations as a veterinarian. Presentations are five-minutes-long followed up with two minutes of a question-and-answer session with members of the audience and the assessors. Notes are not permitted but the student can use teaching aids like a white board during the presentation to signpost and to engage the audience. Each student is assessed by two assessors independently. Feedback is written into an online document and the average of both assessors’ scores is used as the final results to avoid time spent trying to reach a consensus. Results with feedback are sent to the student using mail merge to deliver feedback personally to students and to speed up the process.

OTSPAs were first introduced in the Zoological Medicine (ZM) module in the 4th year; this is a module on zoo medicine, conservation, ecology, population biology, and non-traditional companion animal medicine. Following their favourable outcomes, they were incorporated in two other modules, Fundamentals of Veterinary Practice (FVP), which covers professional skills, communication skills, business, and veterinary legislations, and Veterinary Research and Evidence-based Veterinary Medicine (VREBVM) in the 3rd year, that is mainly on research methodology and evidence-based veterinary medicine. All three courses are compulsory modules within the University of Surrey’s undergraduate veterinary degree.

2.2. Ethical Approval

The perception study within this paper was deemed to follow the University of Surrey’s Ethics Committee protocols via the Self-Assessment for Governance and Ethics on the 5 December 2019 and did not require ethical approval (SAGE: 514292-514283-52778719). The predictive value study using assessment data received a Favourable Ethical Opinion by the University of Surrey’s Ethics Committee on the 17 January 2022 (FHMS 21-22 032 EGA).

2.3. Perception Study

The perception study was carried out using a questionnaire and a quantitative descriptive research approach [41] with closed-ended questions and an open-ended question at the end for additional comments. A mixture of positive and negative statements were used to avoid responders going into autopilot and creating bias. Participants (N = 98) comprised undergraduate veterinary students (years 3–5) from the School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Surrey, that had participated in OTSPAs from 2017 to 2020. The questionnaire was available online for four weeks and data were collected using a five-point Likert scale consisting of 20 opinion statements categorised by ‘Preparation’, ‘Content’, ‘Assessment and Feedback’, ‘Interaction/groupwork skills’, ‘Enjoyment’, and ‘Lifelong Learning’. The Likert scale ranking system used for the statements was 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = do not know/unsure, 4 = agree, and 5 = strongly agree. The first section of the questionnaire collected demographic data followed by the opinion statements and an open-ended question at the end for participants to provide further comments. The questionnaire was piloted on a small group of students at the School of Veterinary Medicine, and the feedback was used to improve the clarity and understanding of the questionnaire which was distributed using JISC Online Survey. All responses were anonymised, with participants giving permission for the data to be used in subsequent analyses.

2.4. Predictive Value Study

OTSPAs were introduced in the Zoological Medicine (ZM) module in the 4th year of the undergraduate veterinary curriculum in 2017, and were later integrated in two 3rd year modules, Fundamentals of Veterinary Practice (FVP) and Veterinary Research and Evidence-based Veterinary Medicine (VREBVM). The total score for the OTSPA was 10 marks (7 marks for content, 2 marks for delivery, and 1 mark for professional behaviour)—see Table 2. The final assessment within all modules consisted of a written summative assessment composed of multiple-choice questions (MCQ) or short answer questions (SAQ). The final written summative assessment (FWSA) captured the breadth of learning objectives within the module. For the purpose of this study, the difference in the FWSA content among the three modules was not evaluated. The OTSPA marks and the ratified marks for the FWSA were downloaded from the University’s assessment portal onto a Microsoft Excel folder. After randomly anonymising identification, data were exported to SPSS Version 27 for statistical analysis. The ZM module had 5 years (2017–2021) of data, FVP had 1 year of data (2018), and VREBVM had 2 years (2019–2020) of data. Missing data points were due to the different ways module coordinators compiled data; these data points were removed and did not affect the study.

Table 2.

Marking rubrics for the On The Spot Presentation-based Assessment.

2.5. Data Analysis

Data were entered into Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). N refers to the number of individuals in each group. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Statistics software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) was used to perform the statistical tests.

With regard to the student perception study, responses to survey items are summarised with percentages and median and mode values. Additionally, we explored how student enjoyment and preparedness for the OTSPA influenced responses to certain items of the survey (including the OTSPA as an authentic assessment and the OTSPA being a good test of student learning). Student enjoyment of the assessment was determined by item 15 on the survey (“I felt OTSPAs were enjoyable”) and categorised into two groups: students that enjoyed the assessment, which includes students that strongly agreed or agreed with the statement, and students that did not enjoy the assessment, which includes students that strongly disagreed or disagreed with the statement. Student preparedness for the assessment was determined by item 3 on the survey (“I feel I prepared well for OTSPAs”) and categorised into two groups: students that prepared well for the assessment, which includes students that strongly agreed or agreed with the statement, and students that did not prepare well for the assessment, which includes students that strongly disagreed or disagreed with the statement. The results are summarised as mean rank of responses ± standard deviation. The non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test investigated for statistically significant differences between groups based on enjoyment and preparedness. Statistical significance was assumed at a p value of <0.05.

The predictive value of the OTSPA was examined for three modules: ZM, FVP, and VREBVM. Histograms and plots were used to confirm that the data were linear and normally distributed. Pearson’s correlations were used to test relationships between scores in the OTSPAs and the FWSA in each module. Linear regression was performed to quantify the association between the two scores. Statistical significance was assumed at a p value of <0.05. Cohen’s effect size interpretations were used to compare strength of correlations where small ≥ 0.10, medium ≥ 0.30, and large ≥ 0.50 [42]. The US Department of Labour, Employment and Training Administration provides guidelines for interpreting correlation coefficients in predictive validity studies where ‘unlikely to be useful’ < 0.11; ‘dependent on circumstances’, 0.11–0.20; ‘likely to be useful’ 0.21–0.35; and ‘very beneficial’ > 0.35 [43].

3. Results

3.1. Student Perceptions of OTSPAs

3.1.1. Student Enjoyment of OTSPAs

In response to the survey item “I felt OTSPAs were enjoyable”, 28 students strongly disagreed and 32 disagreed with the statement. Only 12 agreed and 9 strongly agreed with the statement. This shows that the majority of students did not find the assessment enjoyable.

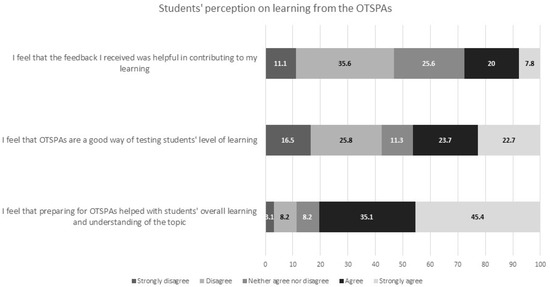

3.1.2. Student Perceptions of Learning from OTSPAs

Three items on the survey explored student perceptions of learning from OTSPAs (Figure 1). Firstly, the majority of students felt OTSPAs achieved their outcome of helping students’ overall learning and understanding of the topic. Secondly, only half of the respondents felt that OTSPAs were a good way to test the students’ level of learning. Only 45.9% agreed with the statement “I feel that OTSPAs are a good way of testing students’ level of learning”, with a similar percentage (42.3%) not agreeing with it. Thirdly, in response to “I feel that the feedback I received was helpful in contributing to my learning”, only 27.8% were in agreement with the feedback being helpful whereas 46.7% felt that the feedback did not contribute to their learning. Furthermore, student enjoyment and preparedness for OTSPAs had a significant effect on the perceived usefulness of the assessment in testing the students’ level of learning. In other words, students who found the assessment enjoyable and those who prepared for the assessment were more likely to agree with the survey item “I feel that OTSPAs are a good way of testing students’ level of learning” (4.35 ± 1.09 vs. 2.45 ± 1.28 at p < 0.001 for enjoyment, and 3.21 ± 1.41 vs. 2.23 ± 1.15 at p = 0.012 for preparedness).

Figure 1.

Stacking bar chart showing the percentages of student responses when asked how strongly they agreed or disagreed with: “I feel that the feedback I received was helpful in contributing to my learning”, “I feel that OTSPAs are a good way of testing students’ level of learning”, and “I feel that preparing for OTSPAs helped with students’ overall learning and understanding of the topic”.

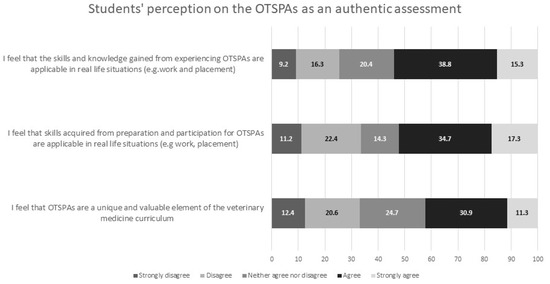

3.1.3. Student Perceptions of OTSPA as an Authentic Assessment

Two items on the survey explored student perceptions of OTSPA as an authentic assessment (Figure 2). Firstly, when asked if skills and knowledge gained from the OTSPA experience was applicable in real life, most of the respondents were in agreement with only a quarter of the respondents in disagreement. Secondly, in response to the statement “I feel that skills acquired from preparation and participation for OTSPAs are applicable in real life situations (e.g., work, placement)”, half of the respondents were in agreement with 33.6% disagreeing and slightly more than 10% who did not know or were unsure. Overall, most students perceive OTSPAs to be an assessment reflecting real-life situations.

Figure 2.

Stacking bar chart showing the percentages of student responses when asked how strongly they agreed or disagreed with: “I feel that the skills and knowledge gained from experiencing OTSPAs are applicable in real life situations (e.g., work and placement)”, “I feel that skills acquired from preparation and participation for OTSPAs are applicable in real life situations (e.g work, placement)”, and “I feel that OTSPAs are a unique and valuable element of the veterinary medicine curriculum”.

3.1.4. Student Appreciation of the OTSPA

In response to students feeling OTSPAs are unique and valuable in the veterinary medicine curriculum, most students were in agreement with this statement (42.2%) while 33% did not agree with this statement at some level. A total of 24.7% of the students had a neutral stand point on this statement (‘neither agree nor disagree’). Overall, most students found value in OTSPAs; however, this is only based on one question asked in the questionnaire.

Furthermore, student enjoyment of and preparedness for OTSPAs had a significant effect on the perceived authenticity of the assessment. Thus, students who found the assessment enjoyable and those who prepared for the assessment were more likely to agree or strongly agree with the following survey items: “I feel that OTSPAs are a unique and valuable element of the veterinary medicine curriculum” (mean score ± SD = 4.35 ± 0.75 vs. 2.5 ± 1.1 for enjoyment, and mean score ± SD = 3.28 ± 1.13 vs. 2.06 ± 1.03 for preparedness), “I feel that skills acquired from preparation and participation for OTSPAs are applicable in real life situations (e.g., work, placement)” (4.1 ± 1.0 vs. 2.8 ± 1.3 for enjoyment, and 3.43 ± 1.27 vs. 2.24 ± 1.09 for preparedness), and “I feel that the skills and knowledge gained from experiencing OTSPAs are applicable in real life situations (e.g., work and placement)” (4.1 ± 0.96 vs. 3 ± 1.2 for appreciation, and 3.52 ± 1.15 vs. 2.41 ± 1.06 for preparedness), at p < 0.001 for all comparisons.

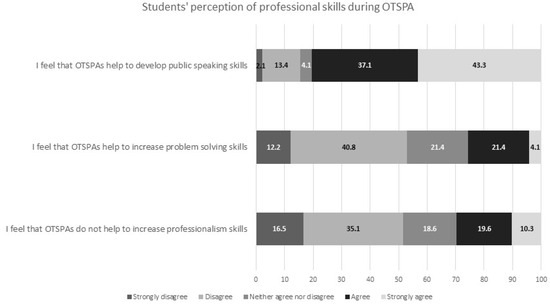

3.1.5. Student Perceptions of Professional Skills Developed through OTSPAs

Three items on the survey explored student perceptions of professional skills’ development through OTSPAs (Figure 3). Firstly, in response to “I feel that OTSPAs help to develop public speaking skills”, 80.4% of students agreed with this and only 15.5% were not in agreement. Secondly, in response to “I feel that OTSPAs help to increase problem solving skills”, the majority of the students did not agree with this statement (53.0%), with only 25.5% being in agreement to the statement. Thirdly, in response to “I feel that OTSPAs do not help to increase professionalism skills”, 29.9% of the respondents were in agreement with this, whereas there were 51.6% who disagreed in different levels with the statement. Thus, most students found OTSPAs to be helpful to develop public speaking professionalism and problem solving skills.

Figure 3.

Stacking bar chart showing the percentages of student responses when asked how strongly they agreed or disagreed with: “I feel that OTSPAs help to develop public speaking skills”, “I feel that OTSPAs help to increase problem solving skills”, and “I feel that OTSPAs do not help to increase professionalism skills”.

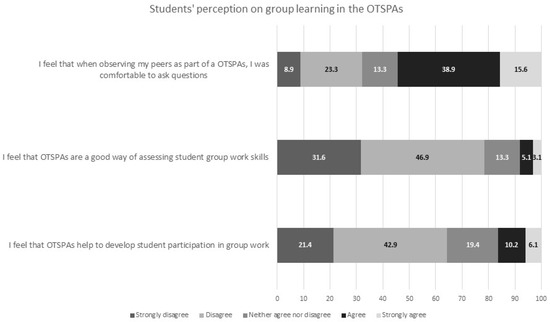

3.1.6. Student Perceptions of Group Learning in OTSPAs

Three items (Figure 4) on the survey explored student perceptions of group interaction during OTSPAs. Firstly, in response to “I feel that OTSPAs help to develop student participation in group work”, 16.3% of respondents were in agreement and 64.3% disagreed. Secondly, in response to “I feel that OTSPAs are a good way of assessing student group work skills”, the majority of the respondents disagreed with this (78.5%) while only 8.2% were in agreement, Thirdly, in response to “I feel that when observing my peers as part of OTSPA, I was comfortable to ask questions”, the majority of students were in agreement at 54.5% while only 32.2% were disagreement. Thus, while most students felt comfortable asking questions, they did not feel that OTSPAs were good at developing or assessing group work skills.

Figure 4.

Stacking bar chart showing the percentages of student responses when asked how strongly they agreed or disagreed with: “I feel that when observing my peers as part of a OTSPAs, I was comfortable to ask questions”, “I feel that OTSPAs are a good way of assessing student group work skills”, and “I feel that OTSPAs help to develop student participation in group work”.

3.2. Predictive Value of the OTSPA in End-of-Module Exams

3.2.1. Predictive Value of the OTSPA in the Zoological Medicine (ZM) Module

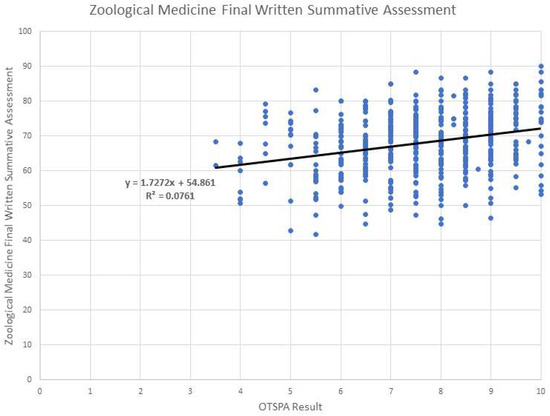

Students’ results in the OTSPA and the final written summative assessment (FWSA) in the Zoological Medicine module were collected over 5 years (2017–2022) for a total of 528 students. These results were combined for an overall analysis. The mean OTSPA score was 7.68 ± 1.39, whereas the mean final assessment score was 68.13 ± 8.72. Pearson’s r correlation between the OTSPA and final assessment scores was 0.276 (p < 0.001), indicating a statistically significant correlation of small strength that is likely to be useful. The r2 value was 0.076 (adjusted r2 0.074), indicating that the OTSPA score can account for 7.6% of the variability in the final assessment scores (Figure 5). A linear regression analysis of the association shows unstandardised coefficient beta 1.727 (95% confidence interval: 1.212–2.243), indicating that for each unit a mark increase in OTSPA score predicts an increase of 1.727 marks in the final assessment score.

Figure 5.

Scatter graph with trendline showing the correlation between the OTSPA result and the Zoological Medicine Final Written Summative Assessment.

3.2.2. Predictive Validity of the OTSPA in the Fundamentals of Veterinary Practice (FVP) Module

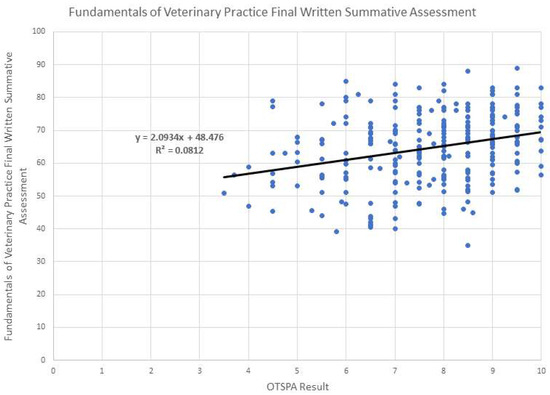

Students’ results in the OTSPA and the final written summative assessment (FWSA) in the FVP module were collected over 2 years (2019–2021) for a total of 272 students. The mean OTSPA score was 7.68 ± 1.45, whereas the mean FWSA score was 64.55 ± 10.68. Pearson’s r correlation between the OTSPA and FWSA scores was 0.285 (p < 0.001), indicating a statistically significant correlation of small strength that is likely to be useful. The r2 value was 0.081 (adjusted r2 0.078), indicating that the OTSPA score can account for 8.1% of the variability in the final assessment scores (Figure 6). A linear regression analysis of the association shows unstandardised coefficient beta 2.093 (95% confidence interval: 1.25–2.937), indicating that for each unit a mark increase in the OTSPA score predicts an increase of 2.093 marks in the FWSA score.

Figure 6.

Scatter graph with trendline showing the correlation between the OTSPA result and the Fundamentals of Veterinary Practice Final Written Summative Assessment.

3.2.3. Predictive Validity of the OTSPA in the Veterinary Research and Evidence-Based Veterinary Medicine (VREBVM) Module

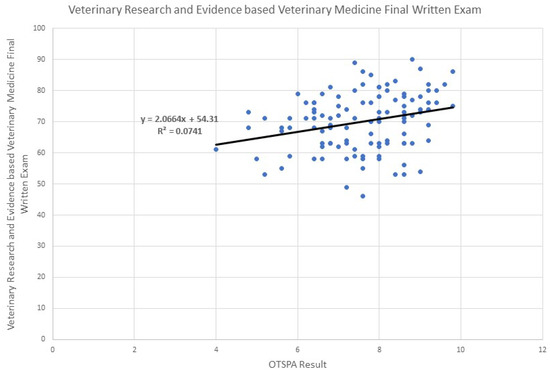

Students’ results in the OTSPA and the final written summative assessment in the VREBVM module were collected for the academic year 2018–19 for a total of 112 students. The mean OTSPA score was 7.57 ± 1.22, whereas the mean final assessment score was 69.96 ± 9.29. Pearson’s r correlation between the OTSPA and final assessment scores was 0.272 (p = 0.004), indicating a statistically significant correlation of small strength that is likely to be useful. The r2 value was 0.074 (adjusted r2 0.066), indicating that the OTSPA score can account for 7.4% of the variability in the final assessment scores (Figure 7). A linear regression analysis of the association shows unstandardised coefficient beta 2.066 (95% confidence interval: 0.686–3.447), indicating that for each unit a mark increase in the OTSPA score predicts an increase of 2.066 marks in the final assessment score.

Figure 7.

Scatter graph with trendline showing the correlation between the OTSPA result and the Veterinary Research and Evidence-based Veterinary Medicine Final Written Exam.

4. Discussion

4.1. Student Perceptions of the OTSPA

The aim of this study is to assess the use of the OTSPA as a low-stake summative assessment that drives learning and as an outcome-based assessment in higher education. OTSPAs took place outside a clinical or professional setting and yet slightly more than half of the respondents felt that OTSPAs help them develop skills that prepare them for life as a veterinarian in practice [20]. This finding supports the OTSPA as an authentic assessment and compliments veterinary education literature reporting that communication skills are an important professional (non-technical) competency for graduate success and the only professional competency consistently found in all categories of evidence studied [44]. Recognising the value of the competency is not enough unless it is effectively infused into the curriculum. Taking a constructive alignment approach to use this assessment not just to achieve deep learning of the subject matter but to understand the achieved non-technical outcomes like public speaking is clearly recognised by the students [40]. Student participation in OTSPAs increased their exposure to practising communication skills in a supportive learning environment within the veterinary curriculum. Inherently this would contribute to the Reflective Relationships–Collaboration and Communications Day One Competency requirement by the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons [27]. Having to think on the spot and present to the group in common language which has less scientific terminology encouraged students to think about avoiding jargon, speaking clearly, and ensuring that the audience understands what is being said. This will help students gain the transferable skill of being able to use uncomplicated and relatable language which in turn may help with future client communication. In a study on perceptions of information exchange, pet owners described (1) understanding the client, (2) providing information suitable for the client, and (3) decision making as key areas that would successfully build a partnership relationship with their veterinarian [45]. Authentic assessments of communication skills must be embedded within the curriculum in order to develop veterinarians’ competency in this area in alignment with client expectations.

Additional analysis indicates that students who did not feel that the assessment accurately tested their level of learning were less likely to (i) enjoy the assessment and (ii) agree that the preparation for the assessment improved their understanding. This finding is consistent with Pekrun’s (2006) control-value theory which states that achievement emotions are related to achievement activities or outcomes [46,47]. So should a student feel their outcome was not as intended during an assessment, there may be a negative emotional experience towards the activity leading to a negative feeling for the assessment. While there is no denying that emotions have an association with academic achievement, this raises the question whether student enjoyment is a fair evaluation within higher education. Education psychology should be incorporated when associating student enjoyment to the success of an education activity to avoid misguided understanding of the value of the assessment. Instead, engaging with students and communicating the importance and benefits gained from the assessment should be prioritised to curb students’ negative emotions [48].

According to this study, student perception of enjoying OTSPAs varied, with a majority (61.3%) reporting not having enjoyed the assessment. This was not investigated further in this study but is potentially due to the novelty of the assessment within the curriculum and/or the pressure felt by students due to having to be put ‘on the spot’. Furthermore, consideration should be made of whether student enjoyment is an accurate measure to be assessed, considering the ‘wicked’ problem of student dissatisfaction with assessments [49]. Despite a low level of enjoyment for OTSPAs being reported, the majority of students (80.5%) felt that preparing for OTSPAs encouraged better learning and understanding of the topics and supported the achievement of the modules’ learning outcomes.

Additionally, the OTSPA is a good tool to use to drive learning in subjects where intrinsic motivation in students is low. All three modules that adopted OTSPAs were subjects that did not historically have high levels of engagement or interest among students due to a perception of the subject being less clinically focused compared to subjects like clinical medicine, surgery, etc. The level of student engagement with a subject area should be a consideration when selecting the types of assessments to be used within higher education. A balanced consideration of student learning needs to be made when selecting summative assessments that provide extrinsic motivation stemmed from the risk of failing examinations [5,50] and providing support to allow an increase in self-efficacy [38]. So, it might not just be a summative or formative assessment that is appropriate but a ‘blended’ assessment such as the OTSPA which offers elements of both.

The OTSPA rubrics included a higher mark for content that evidenced that the student used additional resources to read around the topic and be able to provide different examples than what was covered during the teaching session. Only 27.8% of the respondents felt that the feedback that was provided by the two assessors in a written format after the assessment was helpful. This is despite the OTSPA feedback being delivered within a timely manner [49] a few days after the assessment, which was much earlier than the three-week requirement by the university. There may be a different perception of feedback benefit between written assessments and oral presentations. Further research is needed to understand the value of feedback received in the OTSPA to ensure that the feedback process is effective and impactful in the future.

The OTSPA was not classified as a group assignment although students presented to examiners in the presence of their peers and were able to ask their peers questions. The majority of the students did not feel that the assessment helped with group work skills (either participation in group work or assessing group work skills). However, over half (54.5%) of the students felt that peer observation and presenting in a group made them feel more comfortable to answer questions. This finding supports one of the aims of developing the OTSPA, which was to have a summative assessment that drives intrinsic motivation in a supportive and safe learning environment. Students would be in a positive psychological state that would drive self-efficacy and motivation [37,48]. This evidences the need to avoid taking students out of potentially stressful learning situations like oral assessments, but instead to provide more support to allow them to grow their confidence in their ability to achieve a task [37,38].

4.2. Predictive Value

Within all three modules (ZM, FVP, and VREBVM) there was a small but significant positive correlation between the OTSPA and the FWSA. Findings indicate that a student who did well in OTSPAs will most likely do so in the final assessment within the module. The three modules had very different content that was assessed and assessments were carried out at different time points within the programme year. Despite the differences, there was a consistent predictive relationship that the OTSPA marks were positively correlated with the FWSA. Meagher et al. (2009) described a similar prediction in a team-based formative clinical assessment and its relationship to a final assessment [9]. This predictive ability will identify students who have performed with a borderline pass or have failed and would be at risk of a similar outcome the final assessment which contributes to progression and/or continuation of the course. The prediction of a poor outcome for a final assessment will indicate the need for a poorly performing student to receive additional learning and pastoral support to avoid failing the final summative assessments. Using predictive relationships in assessments to improve student performance in high-weightage summative assessments has been discussed in previous studies [51,52]. This would empower students to take personal responsibility of their academic performance by recognising when they require additional support [53]. Furthermore, resit assessments incur additional financial cost and, incidentally, are a contributor to poor academic performance [53,54].

4.3. Future Use of the OTSPA

The findings from this study recognises the OTSPA as a novel low-weightage summative assessment that can be integrated in clinical and non-clinical subjects where better communication skills are an expected outcome, as well as promoting a deeper learning of the subject matter among students. The ‘on the spot’ testing is a unique feature in this assessment, although it is suspected to be the cause of students not enjoying the assessment. However, arguably this aspect of the assessment mimics the real-life questions that may come from clients during a consultation. In a consultation room, clients are in a position to request explanations for a broad range of animal-related topics. A competent veterinarian must be able to assimilate pre-existing knowledge and to communicate it to the client in a manner that is easily comprehended. To address the lack of effective communication skills within the work force, the authors propose that undergraduates be given the opportunity to practise communication skills at various points within the curriculum by incorporating OTSPAs in various modules.

4.4. Limitations

One limitation of the perception study is that it was only conducted in one year despite having student participants from years 3–5. Having a larger sample population would increase the validity of the study. Additionally, there is missed information from respondents who used neutral responses which would have provided a deeper understanding of the reasons. Another limitation is the lack of understanding of how students with various types of disability and neurodiversity responded to the questionnaire to understand a more specific perspective. Lastly, the evaluation carried out by the students is based on their self-evaluation of the individual skills that they had gained, which is critical in terms of the reliability of the measure.

The context of this paper did not include testing the reliability and validity of the OTSPA method. Data collected for this study limited the ability to analyse these aspects, but they will be included in a subsequent study to better understand how the content being assessed matched the learning objectives.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the present study describes an evaluation of a low-weightage summative assessment aimed at promoting deep learning and creating a supportive learning environment. Students felt that OTSPAs facilitated a deeper understanding of the subject, and had an overall positive perception of OTSPAs as an authentic assessment that also helped with their development of public speaking skills. Finally, the OTSPA’s predictive relationship with the final summative assessment can be used to help identify students who may need additional support at an earlier stage.

Author Contributions

S.J.P. contributed to the conception and design of this study. Y.A.-A. organized the database and data collection. K.S. performed the statistical analysis. S.J.P. wrote the first draft and K.S. wrote sections of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding and the APC was funded by the University of Surrey.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of University of Surrey (FHMS 21-22 032 EGA, 17 January 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy reasons.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the reviewers for their feedback and input towards improving the quality of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

There were no personal or financial conflict of interest that could have caused bias towards the content of this paper.

References

- Ballie, S.; Warman, S.; Rhind, S. A Guide to Assessment in Veterinary Medicine; University of Bristol Press: Bristol, UK, 2014; pp. 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Ontong, J.M. Low-Stakes Assessments: An Effective Tool to Improve Marks in Higher-Stakes Summative Assessments? Evidence from Commerce Students at a South African University. S. Afr. J. High. Educ. 2021, 35, 234–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero, G.; Cárdenas, P. Formative and Summative Assessment in Veterinary Pathology and Other Courses at a Mexican Veterinary College. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 2017, 44, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNulty, J.A.; Espiritu, B.R.; Hoyt, A.E.; Ensminger, D.C.; Chandrasekhar, A.J.; Leischner, R.P. Associations between Formative Practice Quizzes and Summative Examination Outcomes in a Medical Anatomy Course. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2014, 8, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogali, S.R.; Rotgans, J.I.; Rosby, L.; Ferenczi, M.A.; Low Beer, N. Summative and Formative Style Anatomy Practical Examinations: Do They Have Impact on Students’ Performance and Drive for Learning? Anat. Sci. Educ. 2020, 13, 581–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, J. Teacher Education and Professional Development View Project ARIA Nuffield Assessment View Project. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/323319307 (accessed on 18 September 2022).

- Wilkinson, T.J.; Frampton, C.M. Comprehensive Undergraduate Medical Assessments Improve Prediction of Clinical Performance. Med. Educ. 2004, 38, 1111–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusoff, M.S.B. Impact of Summative Assessment on First Year Medical Students’ Mental Health. Int. Med. J. 2011, 18, 172–175. [Google Scholar]

- Meagher, F.M.; Butler, M.W.; Miller, S.D.W.; Costello, R.W.; Conroy, R.M.; McElvaney, N.G. Predictive Validity of Measurements of Clinical Competence Using the Team Objective Structured Bedside Assessment (TOSBA): Assessing the Clinical Competence of Final Year Medical Students. Med. Teach. 2009, 31, e545–e550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-De-La-Peña, M.T.; Baillès, E.; Caseras, X.; Martínez, À.; Ortet, G.; Pérez, J. Formative Assessment and Academic Achievement in Pre-Graduate Students of Health Sciences. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 2009, 14, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadbent, J.; Panadero, E.; Boud, D. Implementing Summative Assessment with a Formative Flavour: A Case Study in a Large Class. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2018, 43, 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huxham, M.; Campbell, F.; Westwood, J. Oral Versus Written Assessments: A Test of Student Performance and Attitudes. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2012, 37, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, M.A.; Joughin, G.R.; Memon, B. Oral Assessment and Postgraduate Medical Examinations: Establishing Conditions for Validity, Reliability and Fairness. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 2010, 15, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGuire, C.H. The Oral Examination as a Measure of Professional Competence. Acad. Med. 1966, 41, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joughin, G. Student Conceptions of Oral Presentations. Stud. High. Educ. 2007, 32, 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thalluri, J.; Penman, J. Case Scenario Oral Presentations as a Learning and Assessment Tool. J. World Univ. Forum 2013, 5, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, T.; Pinar, M.; Trapp, P. An Exploratory Study of Class Presentations and Peer Evaluations: Do Students Perceive the Benefits? Acad. Educ. Leadersh. J. 2011, 15, 77. [Google Scholar]

- Joughin, G. A Short Guide to Oral Assessment; Leeds Met Press in association with University of Wollongong: Leeds, UK, 2010; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hazen, H.; Hamann, H. Assessing Student Learning in Field Courses Using Oral Exams. Geogr. Teach. 2020, 17, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joughin, G. Dimensions of Oral Assessment. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 1998, 23, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preuß, D.; Schoofs, D.; Schlotz, W.; Wolf, O.T. The Stressed Student: Influence of Written Examinations and Oral Presentations on Salivary Cortisol Concentrations in University Students. Stress 2010, 13, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tecles, F.; Fuentes-Rubio, M.; Tvarijonaviciute, A.; Martínez-Subiela, S.; Fatjó, J.; Cerón, J.J. Assessment of Stress Associated with an Oral Public Speech in Veterinary Students by Salivary Biomarkers. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 2014, 41, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Živković, S. The Importance of Oral Presentations for University Students. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2014, 5, 468–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flinders, I.H. Justifying and Applying Oral Presentations in Geographical Education. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 1994, 18, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haigh, M.; Gold, J.R. The Problems with Fieldwork: A Group-Based Approach towards Integrating Fieldwork into the Undergraduate Geography Curriculum. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 1993, 17, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, V. Teaching Oral Communication in Undergraduate Science: Are We Doing Enough and Doing It Right? J. Learn. Des. 2011, 4, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons (RCVS). Day One Competences; RCVS: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- McDermott, M.P.; Cobb, M.A.; Tischler, V.A.; Robbé, I.J.; Dean, R.S. Evaluating Veterinary Practitioner Perceptions of Communication Skills and Training. Vet. Rec. 2017, 180, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hecker, K.G.; Adams, C.L.; Coe, J.B. Assessment of First-Year Veterinary Students’ Communication Skills Using an Objective Structured Clinical Examination: The Importance of Context. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 2012, 39, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, E.; Mossop, L.; Forbes, E.; Oxtoby, C. Uncovering the ‘Messy Details’ of Veterinary Communication: An Analysis of Communication Problems in Cases of Alleged Professional Negligence. Vet. Rec. 2022, 190, e1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazen, H. Use of Oral Examinations to Assess Student Learning in the Social Sciences. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 2020, 44, 592–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryden, L.; Hyder, T.; Jethwa, S. Assessing Individual Oral Presentations. In Investigations in University Teaching and Learning; Spring: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; Volume 1, pp. 79–83. [Google Scholar]

- Grieve, R.; Woodley, J.; Hunt, S.E.; McKay, A. Student Fears of Oral Presentations and Public Speaking in Higher Education: A Qualitative Survey. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2021, 45, 1281–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhati, S.S. The Effectiveness of Oral Presentation Assessment in a Finance Subject: An Empirical Examination. J. Univ. Teach. Learn. Pract. 2012, 9, 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, A.F.; Surur, R.S. The Effectiveness of Oral Assessment Techniques Used in EFL Classrooms in Saudi Arabia From Students and Teachers Point of View. Engl. Lang. Teach. 2019, 12, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino, M.; Mortari, L. The Inclusion of Students with Dyslexia in Higher Education: A Systematic Review Using Narrative Synthesis. Dyslexia 2014, 20, 346–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Perceived Self-Efficacy in Cognitive Development and Functioning. Educ. Psychol. 1993, 28, 117–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, A. The Relationship between Tertiary-Level Students’ Self-Perceived Presentation Delivery and Public Speaking Anxiety: A Mixed-Methods Study. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2020, 45, 1060–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArthur, M.L.; Learey, T.J.; Jarden, A.; Van Gelderen, I.; Hazel, S.J.; Cake, M.A.; Mansfield, C.F.; Zaki, S.; Matthew, S.M. Resilience of Veterinarians at Different Career Stages: The Role of Self-Efficacy, Coping Strategies and Personal Resources for Resilience in veterinary practice. Vet. Rec. 2021, 189, e771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biggs, J. Constructive Alignment in University Teaching. 2014. Available online: www.herdsa.org.au (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Siedlecki, S.L. Understanding Descriptive Research Designs and Methods. Clin. Nurse Spec. 2020, 34, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, C.O.; Morris, P.E.; Richler, J.J. Effect Size Estimates: Current Use, Calculations, and Interpretation. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2012, 141, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husbands, A.; Mathieson, A.; Dowell, J.; Cleland, J.; MacKenzie, R. Predictive Validity of the UK Clinical Aptitude Test in the Final Years of Medical School: A Prospective Cohort Study. BMC Med. Educ. 2014, 14, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cake, M.A.; Bell, M.A.; Williams, J.C.; Brown, F.J.L.; Dozier, M.; Rhind, S.M.; Baillie, S. Which Professional (Non-Technical) Competencies Are Most Important to the Success of Graduate Veterinarians? A Best Evidence Medical Education (BEME) Systematic Review: BEME Guide No. 38. Med. Teach. 2016, 38, 550–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janke, N.; Coe, J.B.; Bernardo, T.M.; Dewey, C.E.; Stone, E.A. Pet Owners’ and Veterinarians’ Perceptions of Information Exchange and Clinical Decision-Making in Companion Animal Practice. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mega, C.; Ronconi, L.; De Beni, R. What Makes a Good Student? How Emotions, Self-Regulated Learning, and Motivation Contribute to Academic Achievement. J. Educ. Psychol. 2014, 106, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R. The Control-Value Theory of Achievement Emotions: Assumptions, Corollaries, and Implications for Educational Research and Practice. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 18, 315–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaessen, B.E.; van den Beemt, A.; van de Watering, G.; van Meeuwen, L.W.; Lemmens, L. Students’ Perception of Frequent Assessments and Its Relation to Motivation and Grades in a Statistics Course: A Pilot Study. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2017, 42, 872–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeley, S.J.; Fischbacher-Smith, M.; Karadzhov, D.; Koristashevskaya, E. Exploring the ‘wicked’ Problem of Student Dissatisfaction with Assessment and Feedback in Higher Education. High. Educ. Pedagog. 2019, 4, 385–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harlen, W.; Deakin Crick, R.; Gough, D.; Bakker, S. A Systematic Review of the Impact of Summative Assessment and Tests on Students’ Motivation for Learning (EPPI-Centre Review, Version 1.1*). In Research Evidence in Education Library; Issue 1; EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Couto, L.B.; Durand, M.T.; Wolff, A.C.D.; Restini, C.B.A.; Faria, M.; Romão, G.S.; Bestetti, R.B. Formative Assessment Scores in Tutorial Sessions Correlates with OSCE and Progress Testing Scores in a PBL Medical Curriculum. Med. Educ. Online 2019, 24, 1560862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Rushood, M.; Al-Eisa, A. Factors Predicting Students’ Performance in the Final Pediatrics OSCE. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayer, M.; De Saintonge, M.C.; Evans, D.; Wood, D. Support for Students with Academic Difficulties. Med. Educ. 2002, 36, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, M.; Abraham, C.; Bond, R. Psychological Correlates of University Students’ Academic Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2012, 138, 353–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).