Abstract

This research aims to measure the attitudes towards the disability of university students and their perception about the labor insertion of this group through the Scale of Attitudes, a questionnaire on the future professional practice, and an argumentative essay. The sample is made up of 360 students from different university degrees. A mixed methodology is used, which combines quantitative analyses and qualitative, through an assay and its category analysis. Regarding the quantitative results, it is observed that nursing students and those who have a bond of friendship with people with disabilities present better data in both dimensions: future professional practice and attitudes towards disability. The students present better data in future professional practice and the students in attitudes towards disability. Regarding the qualitative results, there is a certain terminological sensitivity towards people with disabilities and the need to establish equal treatment and to eliminate social and labor barriers. Finally, students demand more training to promote a more inclusive society. Research questions related to the type of studies and the link to disability are confirmed. As a future line of research, these results should be analyzed and it should be confirmed if there is a change in trend in terms of the vision of disability.

1. Introduction

The Education 2030 Agenda, presented at the World Education Forum, raised the need to “ensure quality, inclusive and equal education, as well as promoting lifelong learning opportunities for all” [1] (p. 20). Previously, the European Higher Education Area [2] proposed a series of changes that affected the design and structure of university studies and the relationship of the university with society, which allowed students to get in touch with reality, enrich their skills, and implement a more inclusive society with greater social awareness [3]. Thus begins the so-called third mission of the university, based on three approaches: innovation, entrepreneurship, and social commitment. This institutional involvement with the third sector—social commitment—includes the development of synergies with the field of disability, educational–social inclusion, knowledge transfers, and research.

Following this approach, it is necessary to plan and implement care plans for people with disabilities through the strategic lines of universities, both from their institutional statements and from their normative documents. In this line, the V Study on the degree of inclusion of the Spanish University System with respect to the reality of disability [4] urges educational institutions to contribute to the educational, sociocultural, and labor inclusion of people with disabilities.

However, to favor its inclusion, we must understand its meaning. The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities [5] (p. 4) describes them as a person with “long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments that, by interacting with various barriers, may impede their full and effective participation in society, on an equal basis with others.” It is precisely the concept of “interacting with various barriers” that confirms a new vision of disability conditioned by the environment. These barriers can be physical, but also psychic, caused by the lack of awareness of those who share an environment with them.

Annually, the State Observatory on Disability and CERMI publish reports in which they denounce situations of discrimination, encouraging to overcome existing barriers: negative attitudes, stigmas, and stereotypes or lack of understanding towards disability. To evaluate these barriers, the following parameters are used: education, employment, accessibility, independent living, awareness, discrimination, economic policies, etc. This research focuses on three of them: education, employment, and accessibility. In addition, it is based on a holistic view of the person with a disability, which encompasses the three factors defined by the Biopsychosocial Model of the Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF): biological, psychological, and social. In this sense, it takes into account the characteristics of the person with disabilities, their psychological and emotional aspects, the activities they can perform, and the social and environmental context in which they live and develop. Therefore, this research also focuses on aspects such as labor market insertion and social attitudes towards disability.

It is about measuring the attitudes towards disability of university students as well as their vision about the work expectations of this group and their degree of social inclusion. Attitudes are learned and knowledge and experiences related to people with disabilities contribute to the evolution and modification of preconceived beliefs or visions [6,7,8]. For this reason, Ainscow [9], Echeita [10], and Parrilla [11] defend an education that develops good attitudes through the implementation of educational programs with committed environments, which favor representations, perceptions, and positive attitudes towards people with disabilities [12]. This involves working on the cognitive, the affective, and the behavioral [13]. As Escámez [14] states, a person’s attitudes are related to their values, knowledge, and feelings, which, finally, shape their behavior. Therefore, it is necessary to know the attitudes of students towards disability to predict and educate their behaviors.

2. Materials and Methods

This research followed a mixed methodology, combining quantitative and qualitative analyses. For the quantitative study, the SPSS-23 program was used, performing descriptive analyses of mean—to know the average value of the students’ responses regarding attitudes towards disability—and standard deviation to analyze the homogeneity or heterogeneity of the sample with respect to the mean, as well as comparative analyses of means by means of ANOVA of one factor, when comparing three or more groups and the t-test to compare two groups. In all cases, the p value was calculated. The measure of effect in the case of the t-test is measured by the 95% confidence interval.

For the qualitative study, the recommendations of Creswell [15] for the interpretation of the data were followed: identification of topics, coding and constant of key questions, and review of the material, as well as mapping of concepts and relationship of ideas. The category scheme [15,16], called open coding, was constructed from the successive evaluation of the data. It was not based on any concrete or restrictive theory, but was built step by step, generating a discourse from the superficial and general to the deepest and most specific [17]. This research has the support of the Ethics Committee of UCV2017-2018-119.

2.1. Objective and Research Questions

The objective was to measure the attitudes towards the disability of university students and their perception about the labor insertion of this group, through the Scale of Attitudes [8], a questionnaire on the future professional practice, and an argumentative essay. In addition, a series of research questions were established to guide the discussion and establish its degree of agreement with what is socially expected. These research questions are:

- Do students who have a link to disability—family, work and/or friendship—show a better attitude towards disability than students with no link?

- Do women have better attitudes towards people with disabilities than men, both in social relationships and in professional practice?

- Do older students show a better attitude towards disability and its professional inclusion than younger students?

2.2. Sample

A total of 360 students from the degrees of nursing (60%), marine sciences (3%), dentistry (11%), medicine (14%), podiatry (8%), and physiotherapy (4%) from Valencian universities participated. This was a non-probabilistic sampling of convenience. As for the course, 14% are in 1st grade, 12% in 2nd, 62% 3rd, and 12% in 4th. Finally, 77.5% are women and 22.5% men, aged between 19 and 25 years.

2.3. Instrument

A reduced version of the Attitude Scale (31 items) was used [8], because it fit perfectly with the objectives and characteristics of university students. The attitudes towards people with disabilities scale is intended to measure beliefs, perceptions, and attitudes towards people with disabilities. This Likert-type scale asks questions such as: “In general, I feel uncomfortable in the company of a person with a disability” or “People with disabilities are able to adapt to an independent life”. There are four response options (strongly agree, strongly agree, strongly disagree, strongly disagree), with the intention of avoiding neutral responses. The internal consistency of the scale is very good, presenting an ordinal Cronbach’s α = 0.928; McDonald’s ω = 0.971, and a stratified Cronbach’s α = 0.886.

The ad hoc questionnaire collected, on the one hand, through 8 items, data on gender, age, mode of access to the degree, current degree, membership in a youth group, whether they have a disability, and whether they have any family, friendship or professional relationship with a person with a disability. On the other hand, the ad hoc questionnaire collected, through 38 items, information on the relationship between future professional practice and disability. Some of the questions were: “The development of my profession is related to dealing with people with disabilities” or “I believe that a person with a sensory disability can exercise my profession with the same degree of competence as me”. The answers to this questionnaire allowed us to know how students perceive people with disabilities and whether they believe that they can exercise a profession just like them.

In addition, for the qualitative study, an argumentative essay on the relationship between professional practice and disability was used, with the intention that students expose their opinions about disability and establish the relationship with their professional future. This essay allowed us to observe the expression, wording, language, and terminology used in reference to disability and its vision regarding its inclusion in professional life.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Analysis of Quantitative Results

3.1.1. Field of Study

The results according to the degree to which the respondents belong affirm that the best evaluations regarding the future professional practice appeared in nursing (2.82 ± 0.32) and physiotherapy (2.77 ± 0.26), while the lowest averages in dentistry (2.57 ± 0.32) and marine sciences (2.56 ± 0.21). These scores were obtained using the ad hoc questionnaire (38 items). On the other hand, regarding attitudes, the best assessments were shown, again, by students of nursing (2.61 ± 0.17) and physiotherapy (2.66 ± 0.19); while dentistry (2.55 ± 0.13) and marine sciences (2.49 ± 0.15) offered the lowest scores (Table 1). These results were extracted from the Attitude Scale of Verdugo et al. [8] (31 items).

Table 1.

Descriptive variables according to the field of study.

Regarding the comparison of means between the different degrees in both variables, there were differences in the future professional practice between dentistry and nursing (p < 0.001). These differences are significant if one takes into account that both are professions related to health, so it seems to indicate the need to increase training efforts and awareness of disability in all grades, in order to balance and overcome these differences. Many of the studies carried out on the change of attitudes towards disability have been directed to degrees such as teaching, social education, pedagogy, or Master’s degree in secondary teaching [18,19,20,21], confirming that, even if we have information on disability, the incidence of a specific training is positive. This research aimed to go a step further and analyze the perception of disability in degrees that did not have in their curricular plan any training on disability, as recommended by Aguado and Alcedo [18], which recognized the lack of information on disability in many degrees and the need to establish training strategies that overcome these shortcomings.

3.1.2. Link with Disability

The variable link with disability assesses to what extent the relationship or not with people with disabilities affects the vision about it. This was measured through the ad hoc sociodemographic questionnaire, with 8 items, which included a specific question that reads as follows: “Do you have any relationship with disability? family? work? help? friendship?” The analysis, both of the future professional practice and of the attitudes towards disability, showed how people with some type of link with disability obtained better average ratings (Table 2). The best score was found in the future professional practice for those who have a link with disability (2.81 ± 0.34), while the lowest value appeared in the attitudes towards disability of those who do not have a link (2.57 ± 0.16). If we compare the means in both dimensions depending on the existence or not of a link with disability, the results indicate that there were significant differences in both cases (p < 0.01), so we can affirm that people who have a link with disability value significantly better both the future professional practice and the attitudes towards disability. These data are consistent with those obtained by González and Baños [22] on the change of attitudes—more positive—towards disability thanks to empirical work with students. Similarly, Molina and Valenciano [7] demonstrate that contact with people with disabilities is a determining factor in the modification of attitudes and beliefs of students.

Table 2.

Descriptive in terms of disability linkage.

In addition, with the intention of verifying what type of link with disability may be more decisive, it was asked what type of link they had with disability—family, work, care, and/or friendship—(Table 3). Based on this classification, it was observed how the highest average values appeared in the future professional practice, both for those who maintain a bond of friendship (2.88 ± 0.32) and for those who maintain a care bond (2.84 ± 0.34). In contrast, the lowest ratings appeared in the attitudes towards disability of those who have no link of any kind, with an average value of 2.59 (± 0.16). Regarding the possible differences that could exist depending on the links with the disability, the results showed significant differences in the bond of friendship (p < 0.01), evidencing that people who have friends with disabilities think differently about future professional practice. This reinforces the importance of promoting practical experiences between people with disabilities and university students and of creating spaces for coexistence and mutual knowledge.

Table 3.

Descriptive and comparisons according to the type of linkage to disability.

3.1.3. Sex of the Students

The results showed (Table 4) that women obtained a better average assessment in relation to future professional practice (2.77 ± 0.32), while men obtained a higher average in attitudes towards disability (2.61 ± 0.17). These data advanced significant differences between men and women, as maintained by Tripp et al. [23] and Voeltz [24], which obtained better scores in women than in men, contrary to what Gil’s studies [19] affirmed. In our research, there were better results in the attitudes of men towards disability and a more positive vision of women in relation to future professional practice, despite the fact that the research questions that women have a more positive attitude towards disability has been demonstrated in numerous studies [25,26]. In this line, the studies by Abellán et al. [27] confirm this trend with students of teaching, specialty education physics, where the results indicated that men showed a more positive attitude towards disability than women. These results reflect an evolution in the perception of disability, from a care perspective—linked to care and traditionally related to women—to a perception of rights, in which men and women show a greater sensitivity to disability.

Table 4.

Descriptive data and comparison by sex.

The results between men and women were also analyzed according to the grade (Table 5). Regarding the future professional practice, nursing students offered the best ratings, with an average of 2.83 (±0.34) in men and 2.82 (±0.32) in women. Regarding attitudes towards disability, physiotherapy students obtained the best average scores, with values of 2.66 (0.16) for men and 2.66 (0.22) for women. In addition, there were also differences regarding the future professional practice between the students of nursing and those of dentistry.

Table 5.

Descriptive data and comparison according to sex in the different careers.

3.1.4. Age of Students

Finally, it was intended to know if age influences the perception of students, as well as if men and women of different age ranges offer different assessments. To analyze this, respondents were grouped into three different age ranges. Regarding future professional practice, it was observed how all age ranges showed exactly the same mean value, with small variations in their standard deviation (Table 6). The same goes for attitudes towards disability, where—despite the fact that students aged 21 to 23 (2.60 ± 0.16) and those over 24 (2.60 ± 0.19) obtained the best average values—the results were quite similar, without presenting significant differences between any of the groups. Contrary to what we could assume from the initial research questions, the results showed that young people have better attitudes and a better vision of future professional practice in relation to disability than older students. These results contradict the studies by Castellanos et al. [28] and advance a possible change in the mentality of the new generations.

Table 6.

Descriptive data and general comparison of age ranges.

In the analysis between sex and age, among men, the best average ratings in the future professional practice were observed among those over 24 years old (2.76 ± 0.31), while in the case of women they appeared shared between students from 21 to 23 years old (2.77 ± 0.31) and those over 24 (2.77 ± 0.36). With regard to attitudes towards disability, it was observed that, in the case of men, the highest average was in students between 21 and 23 years old (2.64 ± 0.13), while in students between those over 24 years of age (2.60 ± 0.20). (Table 7) In terms of average results, there were no significant differences. This is a striking fact, since one tends to think that the older the better attitude towards people with disabilities.

Table 7.

Descriptive data and comparison by sex of age ranges.

3.2. Analysis of Qualitative Results

After an awareness session on disability, the students were asked to carry out the following reflection: Write an argumentative essay in which you reflect on the relationship between your future professional practice and disability, relying on the knowledge acquired throughout your university studies. The aim of this qualitative test was to respond to the objective of this research. Therefore, the aim was to measure the attitudes of university students towards disability, measuring the attitudes of respect and acceptance, terminology; the attitudes towards personal relationships, treatment; and the attitudes towards work relationships, professional environment. Finally, the impact of university training on the human development of students towards disability and reality was measured.

For the analysis and interpretation of the comments, the recommendations of Creswell [15] were followed: identification of topics, coding and constanting of key questions, and review of the material, as well as mapping of concepts and relationship of ideas. It was an analysis by inductive criterion, carried out from a scheme of categories [15,16], called open coding.

For this study, 49 students from different grades were randomly selected through the saturation method [29]. From the first readings of the material, it was observed that the students had been very involved in the reflections, both in the form and in the extension and explanations, expressing their concerns, insecurities, convictions, and needs regarding the relationship of their future professional practice and disability.

Some of the topics that were expected to be found in the reflections were defined, a priori, by the authors, following the scientific literature, and those that appeared and that seemed relevant were noted. Subsequently, a first reading of the essays was initiated looking for these topics, reviewing concepts, terms, and determining the most outstanding by the students, in a spiral review [15,30]. The different themes were defined:

- Terminology: encompasses all the words used by students to designate the disability and associated terms. It includes terms such as disability, functional diversity, and other related terms.

- Treatment: groups all the words that describe the way of relating to the disability, the behaviors, attitudes or behaviors that they themselves follow or see in others.

- Professional environment: includes words such as work, exercise/professional future or any reference to the degree they are studying.

- Training: brings together everything that students mention about training, in any sense.

After the terminological clarification, the information was organized in content matrices, according to the theme, placing, in the first column, an identifier of each participant and in the second, the words or phrases selected in each theme (Table 8). In some cases, it was observed how similar concepts are placed in one or another matrix. The reason is that the students associated one or the other concepts with terminology or treatment interchangeably in their reflection. It was preferred to preserve the literalness of the expressions associated with each topic to respect the origin of the data as much as possible. In the matrices, only words are reflected in some cases and, in others, phrases, since, in some cases, it much better reflects the meaning.

Table 8.

Matrix of terminology terms.

This matrix ordered the concepts and extracts from the reflections of the students those most used terms and their direct references. From this, a count was carried out to find the most frequent words. It was observed that 27 students used the concept of person with disabilities, a term currently accepted socially and legally. “Person with disabilities” and not “disabled” allows to separate the disability of the person, so that this is only one more characteristic and not an intrinsic part of the person. Ten students maintained the concept of disabled and five spoke of functional diversity, a concept increasingly widespread among Disability Associations.

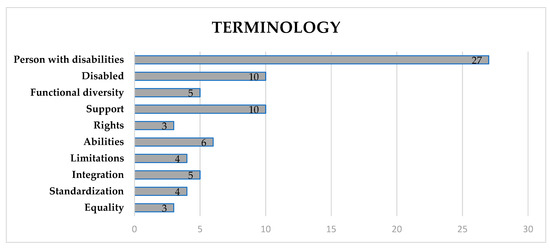

Other interesting terms were observed, such as those referring to help, support for people with disabilities, used by 10 students. This concept of help is related to a paternalistic, charitable vision of disability and assistance and far from the concept of rights of people with disabilities. This concept, that of rights, was barely used by three students. Moreover, it was observed that six students spoke of abilities, a relatively current term, which refers to highlighting, naming, and enhancing what each person has, to the detriment of what they lack, that is, focusing on what they are capable of doing, what qualities and values they have, instead of what their shortcomings, deficits, or limitations are [31]. In contrast, the concept of limitations was used by four students. Other concepts that appeared are integration (five students), normalization (four students), and equality (three students) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Terminology.

Regarding the treatment of persons with disabilities, the following reflections are observed (Table 9), which denote the shortcomings and desires presented by students.

Table 9.

Matrix of terms: deal.

In this matrix, different allusions were observed. A total of 16 students gave importance to the treatment of the person with disabilities and the need to defend equal treatment. It is surprising that two students say that they do not believe that they will have dealings with people with disabilities in their lives. Despite being a minority number, it is still relevant. A total of 15 students referred to the social and physical barriers suffered by people with disabilities. The concept of equality comes out again, this time associated with the deal (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Deal.

Regarding the reflections on the professional environment, some students denounced or demanded measures to normalize the situation with respect to people with disabilities (Table 10).

Table 10.

Matrix of terms: professional environment.

This matrix includes the questions about professional practice, which has to do with their studies and the relationship of these with disability. It is precisely the core of the essay that asked directly about this question. However, only half of the students (26 students) referred directly to this issue. They approached the subject in a very general way, without really delving into or assuming a personal role. They also wrote about the elimination of barriers, especially those that have to do with the physical accessibility of workspaces, highlighting the importance of adapting tools, resources, materials, and the importance of labor inclusion. However, there was some distance in responsibility or commitment to inclusion. Phrases included: society is, society should, society should not, society should not, society should change. Ten students alluded to society as something external, separate from their own experiences or realities, in many cases as something immutable.

As for training, students demand more training on disability and their way of acting with them (Table 11), evidencing the gaps in the training system in that sense.

Table 11.

Matrix of terms: training.

Although the essay did not ask, half of the students added in their reflections assessments on training. For this reason, it was decided to include the topic of training and analyze what the students said. A total of 30 students recognized the importance of the training received, although they find it scarce. They claimed to be aware of a new need, not previously perceived, and stated that they need information, especially about communication, types, and degrees of disability and treatment of the person. In contrast, a couple of students claimed to not need this training, considering it far from their future professional practice and their interests. The fact of finding these statements so resoundingly confirms the need for this training.

In summary, the analysis of qualitative data showed that students hardly delve into their future professional practice and are not very clear about this relationship, apart from the purely care perspective. Students are confused with disability terminology and have uncertainty about disability use. As perceived in the results, half of the students admitted the need for more information, more knowledge, and even dared to contribute concrete topics on which they would like to be trained. In this sense, as it appeared in the analysis of the empirical part, the importance of the link with people with disabilities and the differences in the expression and language of these with respect to those who do not have any type of link was also observed.

4. Conclusions

In relation to the answer to the research questions posed, based on the results obtained, it can be stated that:

Students with a link to people with disabilities present, widely, a better attitude towards them and their development in the social and labor context, evidencing the need to promote the normalization of disability, increase awareness campaigns, and promote experiences of knowledge and coexistence among people.

Female students show better attitudes towards people with disabilities than male students, but only in one of the two variables, specifically in that of future professional practice. In the variable of attitudes, it is the men who show better results. Whether these results confirm a change in trend will have to be verified in future research.

Finally, as to whether older students have a better attitude towards disability, the results show the opposite. Without major differences, it is noteworthy that younger students show a better perception towards disability. These data, together with the second of the research questions posed regarding differences between males and females could indicate a change in trend.

As for qualitative research, the information set aside by the students allows us to predict a significant change in the attitudes, perceptions, and beliefs of university students towards disability and a hopeful advance towards normalization and coexistence in a society of all.

The students present an attitude of respect, help, and support towards people with disabilities. They recognize their rights and refer to them in respectful terms, recognizing the person, what is common to all, and not simply what differentiates them. In addition, they present a favorable attitude towards personal relationships with people with disabilities. They show equal, normalized treatment and place value on the need to eliminate physical, social, and cultural barriers, as one of the students maintained: “I think we should all relate to people with disabilities and get to see people and not their disability, as this should not be a barrier between two people”. Finally, they present an uncommitted and not very personal attitude, towards their labor insertion, showing a distant and not very empathetic attitude.

Therefore, there is a need for a commitment to the training of university students on disability, in order to promote an egalitarian society, with rights and inclusiveness.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.R.-H. and R.S.-P.; methodology, M.R.-H. and R.S.-P.; formal analysis, M.R.-H. and R.S.-P.; investigation, M.R.-H. and R.S.-P.; writing—original draft preparation, M.R.-H. and R.S.-P.; writing—review and editing, M.R.-H. and R.S.-P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee) of Catholic University of Valencia (protocol code UCV2017-2018-119 and 12-20-2018) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- UNESCO. Foro Mundial para la Educación. In Declaración de Incheon, Corea del Norte Educación 2030; UNESCO: Incheon, Republic of Korea, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bologna Declaration. Process and the European Higher Education Area; Bologna Declaration: Bologna, Italy, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Zabalza, M.A. El Practicum y las prácticas en empresa. Rev. Práct. 2013, 1, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Fundación Universia. V Estudio Sobre El Grado de Inclusión Del Sistema Universitario Español Respecto de la Realidad de la Discapacidad; Fundación Universia: Madrid, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- ONU. The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities; ONU: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hodge, S.; Davis, R.; Woodard, R.; Sherrill, C. Comparison of Practicum Types in Changing Preservice Teachers’ Attitudes and Perceived Competence. Adapt. Phys. Act. Q. APAQ 2002, 19, 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina, J.; Valenciano, J. Creencias y actitudes hacia un profesor de educación física en silla de ruedas: Un estudio de caso. Rev. de Pedag. del Deporte 2010, 19, 137–149. [Google Scholar]

- Verdugo, M.A.; Schalock, R. Discapacidad E Inclusión: Manual Para la Docencia; Amarú Ediciones: Salamanca, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ainscow, M. Desarrollo de Escuelas Inclusivas; Narcea: Madrid, Spain, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Echeita, G. Educación Para la Inclusión O Educación Sin Exclusiones; Narcea: Madrid, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Parrilla, A. El desarrollo local e institucional de proyectos educativos inclusivos. Perspect. CEP 2008, 14, 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Rello, C.; Garoz, I. Actividad físico-deportiva en programas de cambio de actitudes hacia la discapacidad en edad escolar: Una revisión de la literatura. Cult. Cienc. y Deporte 2014, 9, 199–210. [Google Scholar]

- Luque, D.; Luque-Rojas, M. Conocimiento de la discapacidad y relaciones sociales en el aula inclusiva. Sugerencias para la acción tutorial. Rev. Iberoam. de Educ. 2011, 54, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Escámez, J. La perspectiva cognitiva para la comprensión de las intenciones y la predicción de las conductas del estudiantado como agente de sostenibilidad. In La Ciudadanía Europea Como Labor Permanente; Arrufat, A., y Sanz, R., Eds.; Tirant lo Blanch: Valencia, Spain, 2019; pp. 211–232. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approach; Sage: Thousands Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano, V.L.; Gutmann, M.L.; Hanson, W.E. Advanced Mixed Methods Research Designs; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A. Qualitive Analysis for Social Scientists; University of Cambridge Press: Cambridge, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Aguado, A.L.; Alcedo, M.; y Arias, B. Cambio de actitudes hacia la discapacidad con escolares de Primaria. Psicothema 2008, 20, 697–704. [Google Scholar]

- Gil, S. Perfil actitudinal de alumnos del Máster en Formación del Profesorado de Educación Secundaria ante la discapacidad. Estudio comparativo. Rev. Nac. e Int. de Educ. Incl. 2017, 10, 133–146. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, F.; Rodríguez, I.; Saldaña, D.; Aguilera, A. Actitudes ante la discapacidad en el alumnado universitario matriculado en materias afines. Rev. Iberoam. de Educ. 2006, 40, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polo, M.T.; Fernández, C.; Díaz, C. Estudio de las actitudes de estudiantes de Ciencias Sociales y Psicología: Relevancia de la información y contacto con personas discapacitadas. Univ. Psychol. 2011, 10, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, J.; Baños, L.M. Estudio sobre el cambio de actitudes hacia la discapacidad en clases de actividad física. Cuad. de Psicol. del Deporte 2012, 12, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripp, A.; French, R.; Sherrill, C. Contact theory and attitudes of children in physical education programs toward peers with disabilities. Adapt. Phys. Act. Q. 1995, 12, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voeltz, L. Effects of structured interactions with severely handicapped peers on children’s attitudes. Am. J. Ment. Defic. 1982, 86, 380–390. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- García-Fernández, J.M.; Inglés, C.J.; Vicent, M.; Gonzálvez, C.; y Mañas, C. Actitudes hacia la discapacidad en el ámbito educativo a través de SSCI (2000–2011). Análisis temático y bibliométrico. Electron. J. Res. Educ. Psychol. 2013, 11, 139–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvack, M.; Ritchie, K.; Shore, B. High and Average Achieving student´s perceptions of disabilities and of students with disabilities in inclusive classroom. Except. Child. 2011, 77, 474–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abellán, J.; Sáez, N.M.; Reina, R. Evaluación de las actitudes hacia la discapacidad en educación física: Efecto diferencial del sexo, contacto previo y la percepción de habilidad y competencia. Cuad. Psicol. Deporte 2018, 18, 133–140. [Google Scholar]

- Castellanos, C.M.; Gutiérrez, A.D.; Castañeda, J.G. Actitudes hacia la discapacidad en educación superior. Incl. y Desarro. 2018, 5, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Sampieri, R.; Fernández-Collado, C.; y Baptista, P. Metodología de la Investigación; McGraw-Hill España: Madrid, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Stringer, E.T. Action Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum, M. Crear Capacidades: Propuesta para el Desarrollo Humano; Paidós: Barcelona, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).