Abstract

In Egypt’s higher education system, there are differences among universities about the compulsory nature of class attendance. In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic, which saw a transition of higher education activities to online environments, has led, after the return to face-to-face learning, to an update on the usefulness of face-to-face learning for higher education students. This work provides quantitative exploratory research on the assessment of university students in the areas of economics and business in Egypt about attendance to face-to-face lectures, its advantages and disadvantages, and the usefulness of implementing new learning methodologies within the lectures. As a result, it has been obtained that the participating students valued attendance as an important element of their learning, although they identified disadvantages in this regard. In addition, they supported the development of active and collaborative methodologies in lectures. It is proposed that this research should be extended to compare the results with those of other geographical areas, and it is suggested that universities increase the adoption of new learning methodologies through the adoption of measures, such as teacher training, in this regard.

1. Introduction

The higher education sector in Egypt is undergoing a massive step-change. There are around 3 million undergraduate students in Egypt, of whom half a million attend its 36 private universities, whilst the rest study at any of the 27 public universities and technical colleges spread throughout the country. Combining faculty members and teaching assistants, there are over 126,000 people teaching in higher education institutions [1].

In 2021, the online platform SCImago Journal & Country Rank ranked Egypt first in Africa and 26th in the world in terms of the h-index: a metric that measures the productivity and citation impact of the academic publications produced in each country [2].

The two main factors influencing the decision of whether to study at a public or a private university in Egypt are the scores obtained at the secondary school leaving exams and the ability to pay for private education [3]. In Egypt, most private universities have implemented a policy of non-compulsory attendance to lectures for their undergraduate students. However, they define attendance at tutorials, seminars, and lab sessions as mandatory. In turn, most public universities maintain the obligation for students to attend lectures.

The debate about whether it is convenient to establish that lecture attendance is compulsory or not is not new, and the academic literature on the topic is vast. However, there is a dearth of studies that focus on Egypt, despite the size of the university sector and its growing trend.

One argument in favour of turning lecture attendance optional is that information and communication technologies (ICT) are playing an increasingly central role in the distribution of knowledge, deploying content 24 h a day everywhere so students can substitute the traditional 2-h on-site lecture with, for example, podcasts, videos, blogs, and hypermedia texts available on the Internet [4]. On the other hand, blended learning tools (i.e., combining e-learning and face-to-face teaching) can also be implemented as an alternative to full-on face-to-face programs. Therefore, the discussion between optionality and an obligation to attend lectures can be framed within the wider conversation about the role of ICTs in undergraduate university education.

On this topic, several studies have been carried out in Egypt, all of which conclude that the use of ICTs is widespread among undergraduate students in the country. For example, a survey from 2015 found that 80 percent of undergraduate Nursing students in a public university in Egypt used ICT to carry out their study assignments and research [5]. However, the specialized literature supports that the process of ICT integration in higher education institutions in Egypt should be intensified and accelerated to ensure appropriate training for the labour market and to enhance the learning experience of students [6,7]. The specialized literature recognizes that non-face-to-face teaching can be as effective as traditional face-to-face teaching in terms of students’ acquisition of knowledge and skills [8,9]. In this sense, the development of new technologies at the service of educational processes increases options in the sense that it offers new communicative possibilities with students and allows the design of sophisticated didactic resources that positively influence the effectiveness of learning [10]. However, the literature also points out some weaknesses that the remote teaching system may have, such as the difficulty it entails for the execution of collaborative activities or the decrease in socializing opportunities among students [10]. For this reason, hybrid teaching models have emerged strongly, combining the use of digital technologies that offer the possibility of carrying out remote activities with a certain degree of face-to-face presence [11]. In addition, studies suggest that attendance favours students’ academic performance [12]. The studies that have been published after the pandemic also show that the groups of students who have maintained the highest levels of attendance in their studies are those who have obtained better learning results [13]. However, as far as we have been able to explore, no research has been found that complements these results with the student’s perspective.

The Italian painter Laurentius de Voltonina rendered a famous pictorial depiction of Henry of Germany lecturing students at the University of Bologna in the 14th century AD, the original of which can be seen at Staatliche Museen in Berlin, Germany. Some of the students are attentively listening to the lecturer, and some are reading—quite possibly following on the pages of their books what Henry of Germany was saying—whilst others are talking, and even a few, sleeping. Except for the clothes, the architecture, and the missing students checking their mobile phones, the picture could well reflect what goes on in many lecture halls in universities around the world.

Lectures have been defined as “predominantly oral methods of giving information, generating understanding and creating interest” [14], p. 41. Standard, expository lectures are the most popular teaching method in universities worldwide, despite the fact that they are less conducive to active student participation in the learning process as they mostly require that students listen, memorize, and take notes, and therefore, do not encourage deep learning approaches [15]. As mentioned above, lectures are ‘predominantly oral’ instructional methods, but they do not need to be wholly passive experiences. Three main variants have been distinguished: the ‘reading’ lecture (portrayed in Voltonina’s painting), in which the lecturer reads out from notes or other printed materials; the ‘conversational’ lecture, in which there are more opportunities for interaction with and among students—also known as ‘interactive’ lectures [16]—, and the ‘rhetorical’ lecture, in which the delivery comes closer to an everyday conversation [17]. Therefore, it is not exact to associate lecture-based instruction with passive learning. It depends on the lecturer’s style: their use of unexpected questions [18], humor [19], aside comments [20], and personal pronouns to address individual students all make a difference in the level of interactivity [21,22].

Part of the literature on higher education pedagogy has embarked on a quest to eschew the delivery of lectures and replace them with other learning activities [23,24], especially as the new information and communication technologies have changed the thinking skills of digital natives compared to previous generations of students—that is, the way they write, reason, process and evaluate information, and pose and define problems [25]—in short, it is claimed that students in the digital age think differently from those who are not digital natives [26,27].

Within the theoretical framework of the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology [28,29], many studies have focused on the perceptions and acceptance of digital media and technologies in higher education. Most of the literature concerning this is based on research carried out in developed countries. For example, a German study reported that the majority of students found instant messaging, cloud storage, and recorded lectures very useful [30], while in the United States of America, university students identified eleven benefits of digital technologies for their university education [31]. In contrast, a large body of the literature reports conflicting findings: despite their extensive use of digital media and technologies, including social media, students favor more traditional learning environments and limited use of information and communication technologies in the teaching and learning process [32,33,34]. Similarly, a few studies based in developing countries have also found a more nuanced acceptance and use of digital technologies as part of university education [35,36,37].

This paper seeks to contribute to the literature by reporting on a relatively unexplored country: Egypt. In Egypt, studies on students’ intentions to adopt ICTs have mostly focused on e-learning, that is, on “any type of learning that depends on or is enhanced by online communication using the latest information and communication technologies” [38], p. 80. These studies have tended to identify the following factors underlying those intentions: perceived usefulness, support, platform interactivity and response, availability of resources, and perceived ease of use and satisfaction [38,39,40,41]. Concerning satisfaction with e-learning, a study among private universities reported that e-service quality, interactivity, comfort, and familiarity were positively associated with student satisfaction [42]. Interestingly, one study from 2012 noted that although the majority of university students used the Internet for educational purposes, about half of them preferred on-campus, face-to-face tuition, which led to the authors suggesting the presence of either a lack of appreciation of the net benefits of e-learning or of a degree of resistance to change among students [43] and another survey also carried out in 2012 complemented this finding by highlighting that almost all students in the sample considered that e-learning lacked the effective means to interact among students and between students and teaching staff [44]. These findings were confirmed in a 2014 comparative study of students in Egypt and the United Arab Emirates, which reported a strong preference among students for human interaction as part of their learning process [45]. Other recent studies highlight the importance of teachers’ communicative skills for an adequate transmission of learning, especially in non-face-to-face scenarios [46,47,48], although these results have not yet been confirmed in Egypt.

The COVID-19 pandemic has altered the way universities conduct their affairs and provide their services, as much as all public and private organisations worldwide. In Egypt, universities and schools were suspended on Sunday, 15 March 2020, initially for two weeks, but the measure was extended until 17 October 2020, when all teaching returned to the on-site, face-to-face modality. Over those eight months, all universities were forced to implement online synchronous and asynchronous e-learning teaching. One study carried out after the return to face-to-face teaching investigated the students’ attitudes toward online learning based on their experience during lockdown. It found that 63 percent of respondents disagreed with the statement that “learning is the same in class and at home on the Internet”, and 62 percent reported some difficulty in completing a course solely given on the Internet [49].

In the post-pandemic period, a 2021 study showed that the perceived usefulness of learning environments for students had a decisive influence on their affective and cognitive engagement and, consequently, on their academic achievement [48]. Although that study does not compare learning methodologies but rather evaluates the satisfaction shown by students with online education, it shows that the presence and interaction with the teacher is a positively influential factor in the affective and behavioural dimensions of the student’s learning process [50]. A recent 2022 study on a population of Egyptian veterinary students showed that while two-thirds of students were satisfied with non-face-to-face learning, the proportion of those who believed it could replace face-to-face classes dropped to less than half of the students [51]. In fact, some studies show that a significant proportion of university students in Egypt had to resort to private tutoring to support their learning in the absence of face-to-face tutoring due to the pandemic [52] or that they had to dedicate more hours to study because of not having attended lectures [53]. In other words, it was found that students perceived learning in the context of a lack of presence to not be very effective [54]. In the specific case of Egyptian university students in the area of economics and business, which is the target population of the present study, the specialized literature has shown that students’ satisfaction with non-face-to-face learning is conditional on certain factors, such as access to required technical resources, but they also perceive that the absence of face-to-face classes leads to greater demands on their talent and dedication [55].

Therefore, it would seem that despite current undergraduate students being by and large ‘digital natives’, they do not endorse ICT tools that, in principle, can replace face-to-face teaching and learning practices. In this regard, it has been found that attendance can have a direct impact on academic performance [56] and that it favours performance to the extent that it facilitates student participation and involvement in learning [57]. The literature has also identified some factors, not academic but sociological, that significantly influence student attendance, such as the influence of classmates and friends [58]. This brings us back to the question regarding ICT-based alternatives to lecture attendance. Some scholars have argued that traditional teaching environments have become obsolete as learning among Generation Z and Millennials is taking place outside the university classrooms and libraries and teachers at all levels, from assistants to emeritus professors, are expected to adapt to these trends and consequently adopt curatorial responsibilities, sifting through and choosing learning materials available on the Internet for their students to learn from [59,60,61,62]. Other authors propound replacing face-to-face lectures with flipped classrooms [63], project-based learning approaches [64], learning based on objects, images, and research activities [65], gamification [66,67], or technologies of virtual and augmented reality [68,69].

Among the various stakeholders whose opinions and attitudes regarding how well ICTs can substitute on-site lectures, those of the students themselves are, oddly enough, not well-researched. Student propensities and predilections are simply assumed based upon stereotypical descriptions and listings of alleged characteristics of Generation Z-ers, Millennials, or similar broad classifications. Whilst it is true that Internet penetration is growing (the rate currently stands at 71.9 percent), that cellular mobile connections are practically universal [70], and that it can be safely assumed that the utilisation of connected devices and services is greater among the younger and the relatively better-off members of Egyptian society, it is so that despite some researchers have detected social media addictive behaviour among university students in the country [71,72,73], it does not necessarily follow that undergraduate students would prefer new ICTs as learning environments in parallel or in lieu of on-site, face-to-face lectures. Nevertheless, as mentioned above, students at many universities have the option not to attend lectures. Why do those who decide to attend do so and those who decide not to attend do so? The specialized literature has found some factors that influence absenteeism among university students. Among them are the need to seek time for completing assignments or the abundance of notes and textbooks that allow their lecture attendance [74]. The specialized literature has abundantly studied the relationship between attendance and students’ academic performance, concluding that there is a strong positive correlation between them [75,76]. For this reason, the need to seek new methodological strategies derived from the pandemic has led to the design of hybrid models, or immersive scheduling delivery models, based on the use of interactive didactic materials and the delivery of classes at a distance but synchronously, to preserve the benefits of attendance on academic performance [77]. However, so far, it has not been possible to find works that address the student’s perspective on the importance of attendance, which is the main objective of the present research. Knowing this perspective is important because it will help professors to provide as adequate a role as possible during face-to-face activities within the design of their methodological strategies, following a perspective focused on the students’ interests.

The objective of this paper is then to find answers to these questions in the case of Egyptian students. This study presents exploratory research on the drivers that pull and push undergraduate business and economics students in Egypt towards and away from on-site lectures in higher education institutions where attendance is not compulsory.

The main conclusions of this study are twofold: firstly, that Egyptian undergraduate students in economics and business do not agree that ICTs can effectively replace face-to-face tuition, and secondly, they favour interactive teaching practices within the lecture hall, including gamification, activity-based teaching, and group debates. Higher rates of lecture attendance are less about better Internet connections and the online availability of teaching materials and more about the adoption of novel, active, and collaborative teaching techniques and tools—IT mediated or not—during face-to-face classes in lecture halls, as opposed to traditional lectures.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The target population consists of undergraduate university students in the field of economics and business in Egypt. This area is integrated within the area of Social Sciences, business, and law—subareas of Social and behavioral science, economics, and Business and administration—of the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) of UNESCO [78]. The target population can be qualified as difficult to access due to two main reasons: (i) the institutional barriers that Egyptian universities establish for external researchers to access their students, even when this access has a single research purpose; (ii) given the diversity of communication policies existing in the different university departments, some professors are expressly prohibited from communicating with their students for purposes other than those established by their respective chairs. Following the recommendations established by the literature for obtaining data in populations that are difficult to access [79], social networks were used to access the student samples under consideration, specifically, the LinkedIn® social network.

A non-probabilistic double convenience sampling process was carried out, that is, divided into two stages by convenience in each of them [80,81]. The first stage consisted of contacting university professors, who, in turn, were required to pass the questionnaire designed for the present research among their students. The inclusion criteria for this stage of the sampling were: (i) being a practicing professor at a university in Egypt and (ii) teaching in a degree program in economics and business. Sixty-four professors teaching at 17 different universities in Egypt were selected from one of the authors’ personal contact lists on the LinkedIn® social network. Each of the professors was contacted individually rather than posting and sharing the questionnaire among all the authors’ contacts. Each of them had the objective of the work explained, was provided with the link to the questionnaire and asked to distribute it among their students for completion. In the second stage of the sampling process, the selected professors distributed the link to the questionnaire among their undergraduate students; the criterion for inclusion in this stage was being a student with an undergraduate university degree in economics and business sciences. Student participation was voluntary, free, and anonymous.

A total of 40 students participated in the study, and all the answers provided were considered valid. The low response rate in relation to the number of professors contacted can be explained by the following circumstances: (i) difficulty of access; (ii) the downward trend in responses that, in general, occurs when several stages are included in the sampling process [82,83]; (iii) the survey was administered during the summer period, after the end of final exams and make-up exams.

Among the participants, all were males, except one, so the gender bias in the sample is evident. The ages of the participants varied between 18 and 26 years; the mean age was 21.35 years, with a standard deviation of 1.53 and a skewness coefficient of 0.69. Therefore, age presents some skewness to the right. The median age is 21 years. Most of the participants have studied basic education in private, international schools –a total of 12 students, representing 30.0% of the sample– or national schools –12 students, 30.0% of the total–while 16 students attended public schools –of which, only five of them, 12.5%, studied in public schools in English, and 11 studied in regular public schools, representing 27.5% of the total. The statistics of the chi-square good-of-fit test allowed us to assume that the distribution of the participants by type of basic education received is statistically homogeneous (chi-square = 3.40, df = 3, p-value = 0.3340).

A total of 70% of the participants study in private universities –a total of 28 students–while 30% study in state universities, 12 students in total. There is, therefore, a bias by university tenure in the distribution of participants (chi-square = 6.40, df = 1, p-value < 0.0114). Table 1 shows the distribution of the degrees taken by the participants; there are a total of 14 students studying several degrees simultaneously.

Table 1.

Distribution of participants by degree studied.

2.2. Objectives and Variables

The general objective of the present research is to analyze the opinion of university students on economics and business degrees in Egypt about the usefulness and interest of attendance to face-to-face classes—not compulsory—and the possibility of their substitution by non-face-to-face teaching methodologies. In particular, the following specific objectives were sought: (i) to assess the influence that participating students attribute to the attendance of face-to-face classes for their learning and grades and the level of disadvantage they perceive for attendance; (ii) to analyze the participants’ opinions on the new teaching methodologies applied in lectures and the possibility of these methodologies replacing the traditional lecture class; (iii) to identify the most influential factors in students’ opinions on attendance to face-to-face classes, and their valuation of new innovative methodologies; and (iv) to analyze the influence of the time dedicated to studying and the absenteeism of face-to-face classes by students on their opinions about face-to-face attendance and new learning methodologies.

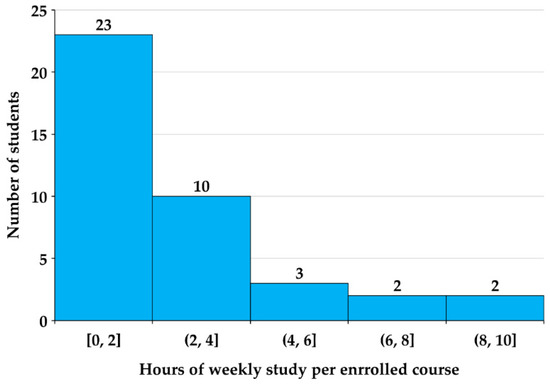

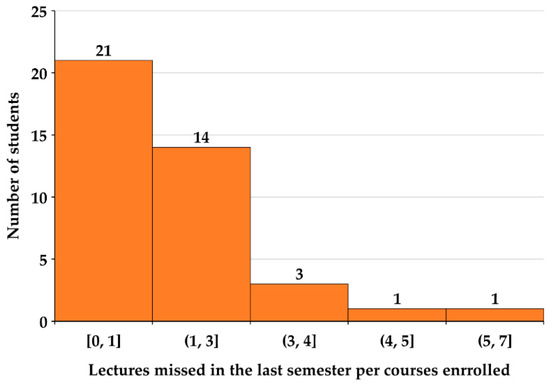

To achieve these objectives, the study considers two independent variables (Figure 1): (i) the number of hours of study per week per enrolled course in the last semester and (ii) the number of lectures missed per enrolled course by the participant students in the last semester. Both variables are ordinal quantitative and have been measured as the quotient of the total number of weekly study hours or lectures missed in the last semester, respectively, by the number of courses enrolled.

Figure 1.

Research variables of the study.

Two dependent variables were also defined (Figure 1): (i) the assessment of the importance of attendance to face-to-face classes; and (ii) the assessment of new non-face-to-face learning methodologies. The expression “non-face-to-face methodologies” refers to the use of new digital technologies to carry out activities mediated by computational tools that, eventually, allow physical and non-face-to-face attendance. This aspect was explained to the students prior to the data collection. Both variables are ordinal quantitative and have been measured on Likert scales from 1 to 5, where 1 means null valuation and 5 means the best valuation.

2.3. Research Instrument and Statistical Analyses

To achieve the research objectives described above, a quantitative descriptive exploratory research study was designed using a self-administered questionnaire designed by the authors and distributed through the Google Forms® platform during the months from June to September 2021. The questionnaire consists of 36 questions or items (Appendix A), all of them Likert-type from 1 to 5, where the value 1 corresponds to the lowest rating and 5 to the highest rating of the aspect that is the object of each of the questions. After the sampling and data collection phases, a statistical analysis of the data was carried out, structured in the following stages: (i) exploratory factor analysis (EFA) of the responses to identify the latent factors or families of questions that explain the responses obtained and relate these factors to the dependent variables defined in the study; (ii) obtaining and analyzing the main descriptive statistics of the factors identified in the EFA; (iii) computation of the Pearson coefficients of the paired correlation of the different pairs of factors defined to identify the influence of some on others; (iv) obtaining the values of the independent variables and the analysis of their distribution; (v) linear regression of the different factors identified with respect to the independent variables to analyze the influence of the latter on the former.

The significance of all the statistical tests has been defined at the 5 per cent level. Despite the size of the sample, statistical tests of the hypothesis contrast those that are robust for small samples, which have been carried out in order to guarantee the greatest possible significance of the results.

3. Results

3.1. Factor Analysis

The EFA identifies nine latent factors that explain the survey responses and that define nine families of questions (Table 2). This theoretical model explains 60.1% of the total variance of the responses (Table 3).

Table 2.

Latent factors identified by the EFA and highest factorial weights for each item (each factor is identified by the letter F followed by the factor number).

Table 3.

Proportion and cumulative proportion of explained variance for the principal component analysis.

Factors 1 to 8 refer to the first dependent variable for the evaluation of face-to-face lessons, while factor 9 measures the second dependent variable for the evaluation of new teaching methodologies. Factor 9 consists of items 32–36 (Appendix A). The factors referring to the first variable are as follows:

- Factor 1 (Influence of lecture attendance on learning and grades): Items 5, 6, 14, 19, 24, 28, 29, and 30;

- Factor 2 (Disadvantages of lecture attendance): Items 4, 7, 10, 16, and 18;

- Factor 3 (Level of encouragement to attend lectures): Items 2, 8, 11, 15, 22, and 23;

- Factor 4 (Utility of using lecture time for other activities): Items 1, 12, 20, 25, and 31;

- Factor 5 (Relevance of the contents covered in the lectures): Items 9, 17, and 27;

- Factor 6 (Utility of tutorials as substitutes for lectures): Item 13;

- Factor 7 (Extent to which lecture attendance impairs socialization): Items 21 and 26;

- Factor 8 (Excessive lecture length): Item 3.

- For the analysis, the answers to items 2, 6, 8, 14, 15, 17, 22, 23, 24, 27, 28, 29, 30, and 31 were inverted to homogenize the meaning, positive or negative, of the questions within each factor. Thus, all the answers have been considered in a positive sense, according to the specific meaning attributed to each of the factors, as described above.

3.2. Analysis of Responses

The influence of lecture attendance on learning and grades, the level of encouragement to attend, and the relevance of its contents are negatively skewed and are rated as intermediate by the participants, who also consider that lecture attendance has a high degree of disadvantages, including its long duration (Table 4). The usefulness of lecture time for other activities or for socializing is rated as intermediate-low and has positive asymmetry (Table 4). However, the evaluation of the new teaching methodologies is high, in general, and the responses in this regard show a higher negative asymmetry than in the rest of the responses (Table 4). The asymmetries of the responses are statistically significant, and the Lilliefors test force us to rule out the possibility that the responses are normally distributed (Table 4). The t-test for the comparison of means does not identify significant differences in the mean responses between students from private and public universities, except in the assessment of the disadvantages of attending lectures, which are identified to a greater extent by students from public universities, and in the assessment of whether attendance hinders socialization: an aspect that students from private universities support to a greater extent than those from public universities (Table 5).

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics of the different families of responses.

Table 5.

Mean ratings (out of 5) of the different families of responses by university tenure of participants and statistics of the t-test for the comparison of means for independent samples.

The different factors identified in the EFA are significantly correlated, although weakly or moderately (Table 6). In this regard, the highest correlations indicate the following: (i) the variable that most positively influenced the valuation of new teaching methodologies was the perceived influence of class attendance on learning and grades; (ii) this perceived influence is lower the higher the valuation of class length is and of the disadvantages of class attendance; (iii) the appraisal of the disadvantages of attendance is positively correlated with the degree to which class attendance hinders socialization; (iv) the level of encouragement to attend class is negatively correlated with the appraisal of excessive class length.

Table 6.

Pearson correlation coefficients of the different factors identified in the EFA (each factor is identified by the letter F followed by the factor number).

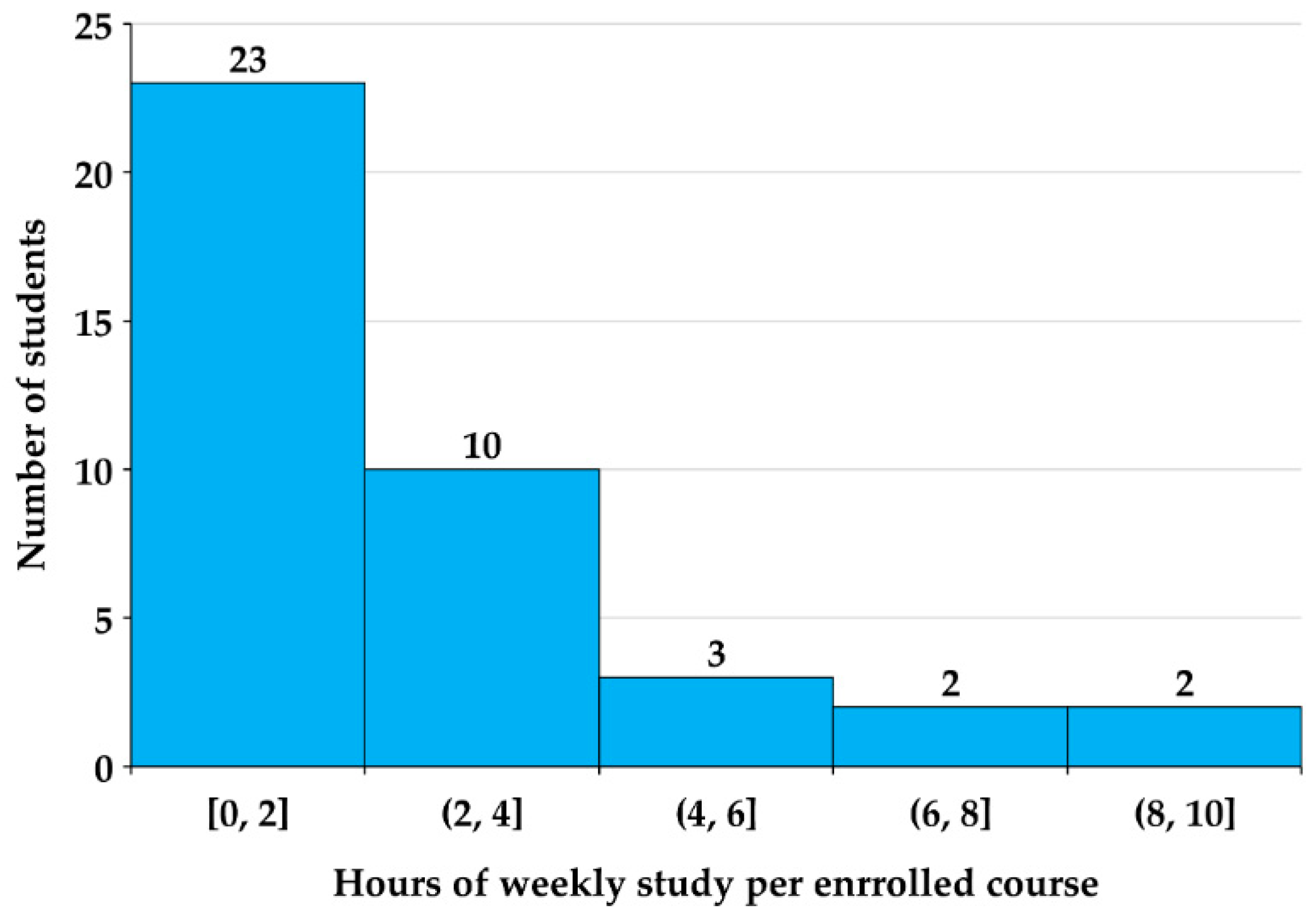

The participating students spent a mean of 2.73 h studying per course enrolled in the last semester, with a standard deviation of 2.39 and a skewness to the right of 1.67 (Figure 2). The median ratio of study time per course enrolled was 1.80. In this sense, students at public universities dedicate, on average, almost one hour more per week to the study of each subject than students at private universities (3.26 h per week of study per subject among students at public universities, compared to 2.38 among students at private universities). This difference in study hours between students from the two types of universities is statistically significant (t-statistic = −3.18, p-value = 0.0017).

Figure 2.

Distribution of participants’ weekly study hours per enrolled course.

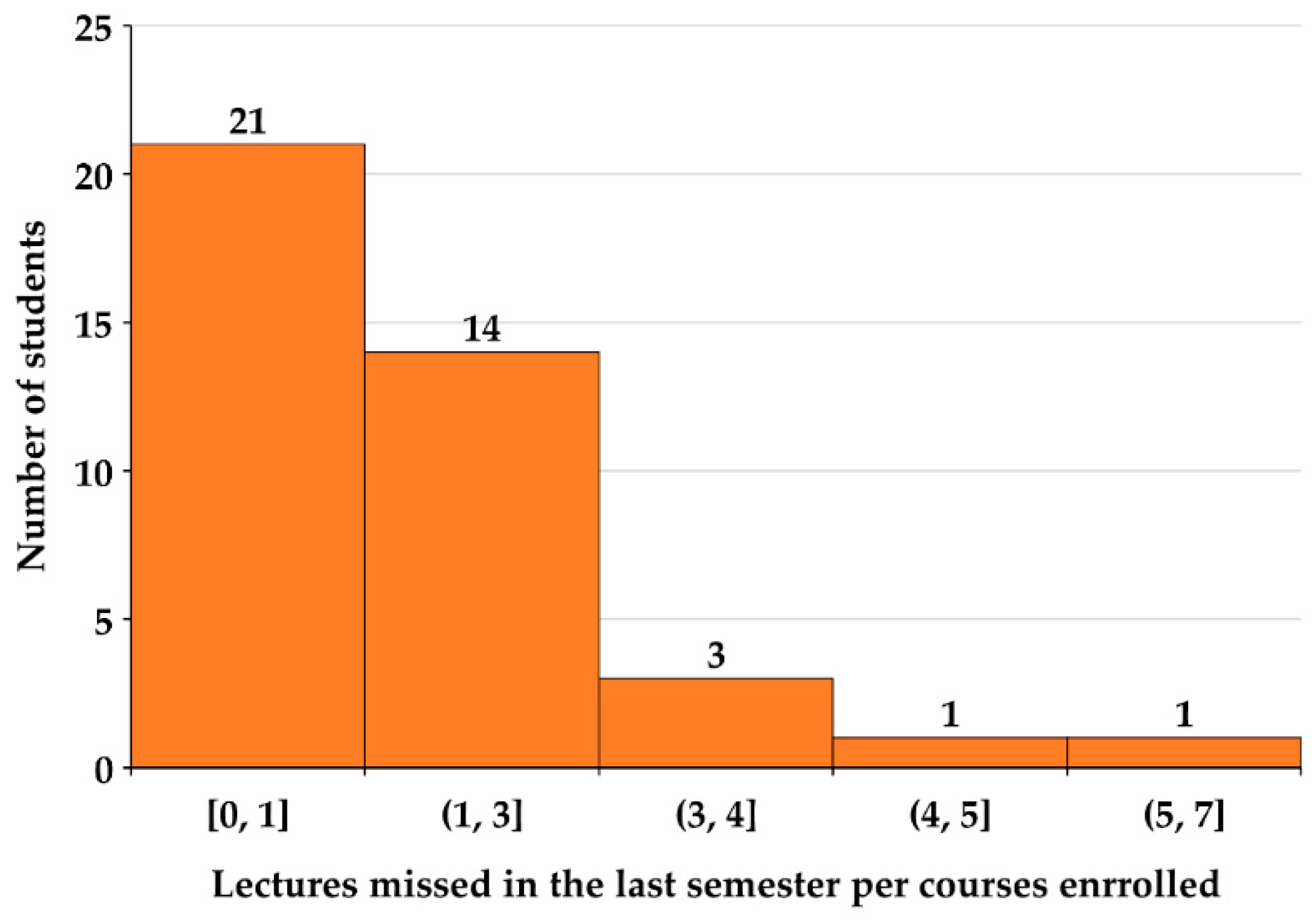

The mean number of lectures missed per course enrolled was 1.42, with a standard deviation of 1.29, a right skewness of 1.30, and a median of 1.00 (Figure 3). This average number of classes missed was slightly higher among students from private universities (1.55) than among students from public universities (1.21), the difference being statistically significant (t-statistic = 2.20, p-value = 0.0287). The Pearson correlation coefficient of the two variables—hours of study and lectures missed by course enrolled—is between0.29 and 0.33 with a confidence level of 95%, and the bilateral Pearson correlation test shows that the two variables are not significantly correlated (t-statistic = 0.1589, df = 38, p-value = 0.8746).

Figure 3.

Distribution of lectures missed per enrolled course.

From the Pearson correlations of the different families of responses with respect to the hours of study spent and the lectures missed per course enrolled (Table 7), the observations from this are as follows: (i) students who perceive a higher level of disadvantages in face-to-face lessons are also those who dedicate fewer hours to study and who miss classes more frequently; (ii) students who show a greater involvement with their studies –i.e., those who dedicate more time to study and who miss classes less frequently–are those who realize to a greater extent that class time could be used for other activities, and are also those who best value the new methodologies; (iii) students who dedicate more time to study and miss face-to-face lessons more frequently are those who most value the relevance of the contents covered in the lessons; (iv) the perceived influence of class attendance on learning and grades is positively correlated with the time dedicated to studying, but negatively correlated with lecture attendance. All the above correlations are moderate but statistically significant.

Table 7.

Pearson bilateral correlation coefficients of the different families of responses with respect to the hours of study dedicated and the lectures missed for each course enrolled.

The number of hours devoted to studying by the students is a variable that discriminates against their assessment of attendance to face-to-face classes. Specifically, it follows from the linear regression models specified in Table 8 that the hours of study have a positive influence on students’ encouragement to attend classes and a negative influence on their assessment of the use of class hours for other teaching activities, given that the corresponding estimated slopes are positive and negative, respectively. This influence is statistically significant because the corresponding p-values are less than the significance level set at 0.05. Moreover, these two are the only variables explained by the number of hours devoted to studying, according to the linear regression models, because they are the only estimated slopes whose associated p-values are below the significance level (Table 8). The assessment of new teaching methodologies is not significantly influenced by the number of hours devoted to studying.

Table 8.

Statistics of the linear regression model for the different factors defined in the EFA with respect to the variable measuring the number of hours of study per enrolled course.

Absenteeism is also an explanatory variable for the evaluation of face-to-face classes, but it is not, following the linear regression model, an explanatory variable for the evaluation of innovative learning methodologies (Table 9). Specifically, the level of absenteeism of participating students in face-to-face classes negatively influences their valuation of the influence of attendance and the encouragement they feel to attend, while it positively reinforces the perceived disadvantages of class attendance and the interpretation of attendance as an impediment to socialization. These conclusions follow from the values of the slopes estimated by the linear regression model and the fact that p-values indicate that the corresponding linear dependencies are statistically significant (Table 9).

Table 9.

Statistics of the linear regression model for the different factors defined in the EFA with respect to the variable measuring the number of lectures missed per enrolled course.

4. Discussion

The Egyptian business and economics students participating in the study gave high ratings, in general, to the importance of attending face-to-face classes, mainly due to the relevance of the content covered in them and the influence that attendance exerts on the learning acquired and the grades obtained (Table 4). These results are in line with previous studies that have shown that despite the fact university students in Egypt make adequate use of online technical teaching resources [5,15,16,17] and are familiar with these tools [18], they do not think that face-to-face attendance is, for the time being, dispensable [43,44,45,51,54]. Participants also seek, albeit moderately, tutoring to make up for missed attendance (Table 4), which is consistent with the increased request for tutoring observed among higher education students in Egypt during the pandemic [52]. Thus, the importance of face-to-face attendance perceived by Egyptian business and economics students is in line with the influence attributed to face-to-face attendance in the literature on the academic performance of university students in general [57]. The above results are also in line with work conducted on a population of Egyptian students with difficulties in accessing digital technologies, whose assessment of the face-to-face nature of lectures is reasonably high [49].

The participants identify that class attendance presents disadvantages, some of them attributable to the communicative qualities of the professor and others to the inconvenience of class schedules. Among these disadvantages, the excessive length of class time is the one most intensely pointed out by the students, who, moreover, indicate it with the smallest dispersion observed among the responses (Table 7). Likewise, the need to take time to complete mandatory assignments has a negative influence on the perception of the importance of attending class (Table 7). This observation is in line with the main factors that have been identified in the recent literature as explanatory of absenteeism [74]. These results are novel in the previous literature, in which there are no studies that analyze the perception of attendance among students with this level of detail. However, it has been shown that the role of the teacher in the development of the teaching-learning process is an influential and determining factor in the student’s attitude toward their own learning [50], which is in line with the results obtained here. The idea that class attendance hinders socialization with peers also feeds the perception of the disadvantages of face-to-face classes (Table 6). This observation is consistent with the strong dependence on the influence of classmates and friends on class attendance in the recent literature [58]. In this regard, participating students from private universities miss classes more frequently than those from public universities, and it is precisely the latter who identify more disadvantages in attendance (Table 5). The higher absence of students from private universities may be explained by the greater technical endowment of this type of university in Egypt, which facilitates the remote monitoring of academic activities [3,42]. The novelty offered here in this regard lies in the fact that the students who most frequently attend class are precisely those who encounter the greatest disadvantages in attendance.

Likewise, the participating students are decisively committed to the incorporation of new teaching methodologies—collaborative methodologies, based on debate and discussion, and active methodologies, such as flipped classroom and educational gamification—to strengthen face-to-face classes and increase the incentive to attend them (Table 4 and Table 6). Therefore, the main proposal derived from the results obtained here is to maintain face-to-face classes, but to rethink the teaching methodology, so that it transitions from the master class to other more active and collaborative methodologies based on cognitive theories that attribute an active role in the construction of knowledge [63,64,65], or that place greater importance on activities by the students, through didactic materials designed for them to work on as part of their own learning process [59,60,61].

As novel results of the present research, it has been shown that the time devoted to personal study and the level of absenteeism of Egyptian business and economics students significantly influence the assessment of the importance of class attendance (Table 8) but not the assessment of the use of new methodologies to be applied in the classroom (Table 9). The previous literature has shown that, among economics and business students in Egypt, absenteeism leads to the need to spend more time studying [55]. However, in this work, it has been shown that more study time leads to a greater incentive to attend class—with an influence manifested in a correlation slope of around 10%—and helps to avoid missing classes to complete academic assignments with an influence whose slope is, in this case, close to 15% (Table 8). In addition, absenteeism from classes fuels a decrease in the evaluation of the importance of classes and in the motivation to participate in them—with influences that reach slopes of around 25%—and the perception of the disadvantages of classes, particularly the negative influence it has on socialization is an aspect in which the influence rises to 30% (Table 9). These results are original to this work and constitute an element of novelty.

5. Limitations and Lines of Future Research

This paper focuses on a population of undergraduate students in the field of economics and business in Egypt. The Egyptian higher education system is very particular in this area, both because of the presence of public and private universities and branches of international universities, which operate in English, and because of the different academic policies according to the type of university, as students in public universities are generally required to be present in master classes, but this is optional in private universities, for example.

These essential peculiarities in the Egyptian case mean that the present study is limited in its results to the geographical area in which it was carried out. Therefore, it would be interesting to carry out a descriptive, comparative, and correlational exploration that would allow comparisons to be made between the Egyptian case and other nearby geographical areas with respect to the variables analyzed. Although robust hypothesis testing has been used for small sample sizes and, consequently, good results have been obtained in terms of statistical significance, it would be advisable, as a future line of research, to increase the size of the sample of students to make it more representative of the population and, consequently, to be able to contrast the results obtained here.

Consequently, it would be interesting to carry out a study similar to the present one, but in which the sampling process is carried out at a different time of the academic year in order to be able to access a wider potential population. Likewise, in subsequent research, the sample should be homogeneous with respect to the student’s gender and university tenure in order to analyze the influence of these sociological or academic variables on the studied students’ perceptions of class attendance and the incorporation of new teaching methodologies in the area of economics and business.

6. Conclusions

This paper has shown that, despite having recently experienced the use of virtual learning environments due to the COVID-19 pandemic, economics and business students in Egypt consider attendance to face-to-face classes to be important. This perception stems mainly from the influence they attribute to attendance on the learning achieved and grades obtained and from the relevance of the topics covered in class. However, the perception of the disadvantages of class attendance is high, mainly because of its excessive length and the time it consumes. In addition, students are strongly in favor of maintaining face-to-face classes but including new, active, and collaborative learning methodologies. Consequently, it is suggested that universities should take measures to facilitate the integration of active learning methodologies in the classroom, particularly the design of teacher training sessions in this regard.

It has also been found that the time dedicated to studying and absenteeism from the class influence the perception of the usefulness of class attendance but not the evaluation of new teaching methodologies. Specifically, more time dedicated to studying results in a better evaluation of class attendance and a reduction in absenteeism. On the other hand, the more classes are missed, the more the spiral of negative perceptions about attendance is fed, including mainly the identification of the disadvantages of classes and the negative impact of attendance on socialization.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.-L.I.; Methodology, J.-L.I. and D.V.; Validation, J.-L.I., Á.A.-S. and D.V.; Formal analysis, Á.A.-S. and D.V.; Investigation, J.-L.I.; Data curation, Á.A.-S.; Writing – original draft, J.-L.I., Á.A.-S. and D.V.; Writing – review & editing, J.-L.I., Á.A.-S. and D.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Faculty of Business Administration at The German International University of Applied Sciences in Cairo. No personal data or data that could be used to identify the participants were collected in any process of the research.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available because they are part of a larger project. If you have any questions, please ask the contact author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Questions of the Survey

| Item Number | Question |

|---|---|

| 1 | I prefer to spend the lecture slots to study for quizzes and exams |

| 2 | My friends do not attend lectures |

| 3 | Lectures are too long |

| 4 | The atmosphere in the lecture room is not pleasant |

| 5 | Lectures are helpful to obtain good grades |

| 6 | Lectures are not necessary to obtain good grades |

| 7 | The lecture contents are too difficult |

| 8 | There are many lectures on the same day |

| 9 | The contents of the lectures are relevant |

| 10 | The lecturer is not an effective communicator |

| 11 | Lectures are stimulating |

| 12 | I use the lecture slots to complete assignments |

| 13 | Tutorials can replace lectures |

| 14 | Online learning resources are sufficient to replace lectures |

| 15 | Textbooks are sufficient replacements to lectures |

| 16 | The lecturer is not skillful |

| 17 | Lecture notes are sufficient to replace attendance |

| 18 | I do not understand the lecturer’s explanations |

| 19 | Lecture attendance counts towards grades |

| 20 | The lecture halls are too noisy |

| 21 | Lecture slides are sufficient to replace the attendance |

| 22 | I cannot be bothered to attend lectures |

| 23 | The lectures take place at inconvenient slots |

| 24 | In general, I do not attend lectures |

| 25 | Tutorials are enough to obtain good grades |

| 26 | I prefer to spend the lecture slots socializing with friends |

| 27 | If I attend the lectures, my friends will tease me |

| 28 | I obtain the grades I want without attending lectures |

| 29 | I can obtain grades that fairly reflect my knowledge of the subjects without attending lectures |

| 30 | If I attend more lectures, I will not obtain higher grades |

| 31 | Compulsory lecture attendance would benefit my studies |

| 32 | More activity-based learning (e.g., doing tasks during lecture times) |

| 33 | More interesting and engaging lecture materials |

| 34 | Group discussions on topics during lectures |

| 35 | Games and competitions during lectures |

| 36 | Bonus assignments during lectures |

References

- Enterprise. The State of the Nation. Higher Education in Egypt: 2014 vs. 2021. Available online: https://enterprise.press/blackboards/higher-education-egypt-2014-vs-2021/ (accessed on 3 October 2022).

- SCImago, (n.d.). SJR—SCImago Journal & Country Rank [Portal]. Available online: http://www.scimagojr.com (accessed on 3 October 2022).

- Abdelkhalek, F.; Langsten, R. Track and sector in Egyptian higher education: Who studies where and why? In FIRE: Forum for International Research in Education; Lehigh University Library and Technology Services: Bethlehem, PA, USA, 2020; Volume 6, pp. 45–70. [Google Scholar]

- Antón-Sancho, Á.; Sánchez-Calvo, M. Influence of knowledge area on the use of digital tools during the COVID-19 pandemic among Latin American professors. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawal, U.B.; Elshafie, I.F.; Yunusa, U.; Ladan, M.A.; Suberu, A.; Abdullahi, S.G.; Mba, C.J. Utilization of information and communication technology among undergraduate nursing students in Tanta university, Egypt. Int. J. Nurs. Care 2017, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elharakany, R.A.; Moscardini, A.; Khalifa, N.M.; Elghany, M.M.A. Modelling the effect on quality of information and communications technology ICT facilities in higher education: Case study-Egyptian universities. Int. J. Syst. Dyn. Appl. 2018, 7, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobaih, A.E.E.; Hasanein, A.; Elshaer, I.A. Higher education in and after COVID-19: The impact of using social network applications for e-learning on students’ academic performance. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurlbut, A.R. Online vs. traditional learning in teacher education: A comparison of student progress. Am. J. Distance Educ. 2018, 32, 248–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanley, E.L.; Thomson, C.A.; Leuchner, L.A.; Zhao, Y. Distance education is as effective as traditional education when teaching food safety. Food Serv. Technol. 2004, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salter, G. Comparing online and traditional teaching—A different approach. Campus-Wide Inf. Syst. 2003, 20, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salajegheh, A.; Jahangiri, A.; Dolan-Evans, E.; Pakneshan, S. A combination of traditional learning and e-learning can be more effective on radiological interpretation skills in medical students: A pre- and post-intervention study. BMC Med. Educ. 2016, 16, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrietti, V.; Velasco, C. Lecture attendance, study time, and academic performance: A panel data study. J. Econ. Educ. 2015, 46, 239–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.; Kim, S.; Chung, K.-M.; Lee, K.; Kim, T.; Heo, J. Is college students’ trajectory associated with academic performance? Comput. Educ. 2022, 178, 104397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G. Lecturing and Explaining; Methuen: London, UK, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Biggs, J. Student Approaches to Learning and Studying; Australian Council for Educational Research: Hawthorn, VIC, Australia, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, N.A.; Masuwai, A. Transforming the standard lecture into an interactive lecture: The CDEARA model. Int. J. Innov. Educ. Res. 2014, 2, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudley-Evans, A.; Johns, T.F. A team teaching approach to lecture comprehension for overseas students. In The Teaching of Listening Comprehension ELT Documents Special; The British Council: London UK, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford-Camiciottoli, B. The Language of Business Studies Lectures. A Corpus-Assisted Analysis; John Benjamins: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nesi, H. Laughter in university lectures. J. Eng. Acad. Purp. 2012, 11, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strodt-Lopez, B. Tying it all in: Asides in university lectures. Appl. Linguist. 1991, 12, 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortanet, I. The use of ‘we’ in university lectures: Reference and function. Eng. Specif. Purp. 2004, 23, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, J. Tools for Teaching in an Educationally Mobile World; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tapscott, D. Grown up Digital: How the Net Generation Is Changing Your World; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, L. Rewired: Understanding the iGeneration and the Way They Learn; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wegerif, R. Literature Review in Thinking Skills, Technology and Learning; Futurelab Series. Report 2; Futurelab: Bristol, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Prensky, M. Digital natives, digital immigrants. Part 1. On Horiz. 2001, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prensky, M. Digital natives, digital immigrants. Part 2: Do they really think differently? Horizon 2001, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. Manag. Inf. Syst. Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.D.; Rana, N.P.; Dwivedi, Y.K. The unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT): A literature review. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2015, 28, 443–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, M.; Marín, V.I.; Dolch, C.; Bedenlier, S.; Zawacki-Richter, O. Digital transformation in German higher education: Student and teacher perceptions and usage of digital media. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2018, 15, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, M.; Selwyn, N.; Aston, R. What works and why? Student perceptions of ‘useful’ digital technology in university teaching and learning. Stud. High. Educ. 2017, 42, 1567–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohnes, S.; Kinzer, C. Questioning assumptions about students’ expectations for technology in college classrooms. Innov. J. Online Educ. 2007, 3, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S.D.; Caruso, J.B. The ECAR study of undergraduate students and information technology. In Research Study; EDUCAUSE Center for Applied Research: Boulder, CO, USA, 2010; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, C.; Shao, B. The Net Generation and Digital Natives: Implications for Higher Education; Higher Education Academy: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo-Echenique, E.; Anchapuri, M. University students’ use and preferences of digital technology in the Peruvian Highlands. In Proceedings of the International Congress on Educational and Technology in Sciences, 26–29 October 2019; pp. 158–167. [Google Scholar]

- Ashour, S. How technology has shaped university students’ perceptions and expectations around higher education: An exploratory study of the United Arab Emirates. Stud. High. Educ. 2020, 45, 2513–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveh, G.; Shelef, A. Analyzing attitudes of students toward the use of technology for learning: Simplicity is the key to successful implementation in higher education. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2020, 35, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, A. The impact of e-learning. In E-Content; Bruck, P.A., Karssen, Z., Buchholz, A., Zerfass, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 79–96. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Wahab, A.G. Modeling students’ intention to adopt e-learning: A case from Egypt. Electron. J. Inf. Syst. Dev. Ctries. 2008, 34, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attalla, S.M.; El-Sherbiny, R.; Mokbel, W.A.; El-Moursy, R.M.; Abdel-Wahab, A.G. Screening of students’ intentions to adopt mobile-learning: A case from Egypt. Int. J. Online Pedagog. Course Des. 2012, 2, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, T.M.; Jones, E.; Hussien, F.M. Technological factors influencing university tourism and hospitality students’ intention to use e-learning: A comparative analysis of Egypt and the United Kingdom. J. Hosp. Tour. Educ. 2016, 28, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Headar, M.M.; Elaref, N.; Yacout, O.M. Antecedents and consequences of student satisfaction with e-learning: The case of private universities in Egypt. J. Mark. High. Educ. 2013, 23, 226–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Gamal, S.; Abd-El-Aziz, R. Improving higher education in Egypt through e-learning programs: HE students and senior academics perspective. Int. J. Innov. Educ. 2012, 1, 335–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Seoud, M.; El-Sofany, H.F.; Taj-Eddin, I.A.; Nosseir, A.; El-Khouly, M.M. Implementation of web-based education in Egypt through cloud computing technologies and its effect on higher education. High. Educ. Stud. 2013, 3, 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Alfy, S.; Gómez, J.M.; Ivanov, D. Exploring instructors’ technology readiness, attitudes and behavioral intentions towards e-learning technologies in Egypt and United Arab Emirates. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2017, 22, 2605–2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Arias, P.; Antón-Sancho, Á.; Vergara, D.; Barrientos, A. Soft skills of American university teachers: Self-concept. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antón-Sancho, Á.; Vergara, D.; Fernández-Arias, P. Self-assessment of soft skills of university teachers from countries with a low level of digital competence. Electronics 2021, 10, 2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Arias, P.; Antón-Sancho, A.; Barrientos-Fernández, A.; Vergara-Rodríguez, D. Soft skills of Latin American engineering professors: Gender gap. IEEE Trans. Educ. 2022; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaoud, H.; El-Shihy, D.; Yousri, M. Online learning in Egyptian universities post COVID-19 pandemic: A student’s perspective. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2021, 16, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayad, G.; Md-Saad, N.H.; Thurasamy, R. How higher education students in Egypt perceived online learning engagement and satisfaction during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Comput. Educ. 2021, 8, 527–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdy, M.A.A.; Sayed, R.K.A. Evaluation of the online learning of veterinary anatomy education during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown in Egypt: Students’ perceptions. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2022, 15, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Issa, S.; Abd-El-Aaty, H.; Gaber, Y.M.; Zaghloul, N.M. Students’ perception of private supplementary tutoring during medical undergraduate study in some Egyptian universities. J. Appl. Res. High. Educ. 2022; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortagy, M.; Abdelhameed, A.; Sexton, P.; Olken, M.; Hegazy, M.T.; Gawald, M.A.; Senna, F.; Mahmoud, I.A.; Shah, J.; Egyptian Medical Education Collaborative Group; et al. Online medical education in Egypt during the COVID-19 pandemic: A nationwide assessment of medical students’ usage and perceptions. BMC Med. Educ. 2022, 22, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, R.; Khalifa, A.R.; Elsewify, T.; Hassan, M.G. Perceptions of clinical dental students toward online education during the COVID-19 crisis: An Egyptian multicenter cross-sectional survey. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 704179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, C.; Salman, D.; Gamal-el-din, G.O. Students’ perceptions of online learning in higher education during COVID-19: An empirical study of MBA and DBA students in Egypt. Future Bus. J. 2022, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.; Armstrong, C.; Pearson, J. Lecture absenteeism among students in higher education: A valuable route to understanding student motivation. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2008, 30, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Cutumisu, M. Online engagement and performance on formative assessments mediate the relationship between attendance and course performance. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2022, 19, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughlin, C.; Lindberg-Sand, Å. The use of lectures: Effective pedagogy or seeds scattered on the wind? High. Educ. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaleniauskiene, E.; Juceviciene, P. Reconsidering university educational environment for the learners of generation Z. Soc. Sci. 2015, 88, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosca, J.B.; Curtis, K.P.; Savoth, P.G. New approaches to learning for generation Z. J. Bus. Divers. 2019, 19, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seemiller, C.; Grace, M. Generation Z Goes to College; Jossey-Bass Publisher. John Wiley & Sons: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Godoy, M.E.; Zúñiga-Garay, E.; Tomljenovic-Niksic, M. Desafíos del profesor de ciencias frente a estudiantes millennials y post-millennials. Rev. Estud. Exp. Educ. 2021, 20, 285–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lage, M.; Platt, G.; Treglia, M. Inverting the classroom: A gateway to creating an inclusive learning environment. J. Econ. Educ. 2000, 31, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott-Webber, L.; Branch, J.; Bartholomew, P.; Nygaard, C. (Eds.) Learning Space Design in Higher Education; Libri Publishing: Oxfordshire, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, K.; Abdullah, A. The collaborative problem-solving questionnaire: Validity and reliability test. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2013, 3, 470–478. Available online: https://hrmars.com/papers_submitted/9443/the-collaborative-problem-solving-questionnaire-validity-and-reliability-test.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- Vergara, D.; Antón-Sancho, A.; Fernández-Arias, P. Player profiles for game-based applications in engineering education. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2022; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergara, D.; Mezquita, J.M.; Gómez-Vallecillo, A.I. Metodología innovadora basada en la gamificación educativa: Evaluación tipo test con la herramienta quizizz. Prof. Rev. Curríc. Form. Prof. 2019, 23, 363–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antón-Sancho, Á.; Fernández-Arias, P.; Vergara, D. Assessment of virtual reality among university professors: Influence of the digital generation. Computers 2022, 11, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergara, D.; Antón-Sancho, A.; Dávila, L.P.; Fernández-Arias, P. Virtual reality as a didactic resource from the perspective of engineering teachers. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2022, 30, 1068–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Communications and Information Technology. ICT Indicators Bulletin 2020. Quarterly Issue. December. Cairo, Egypt. Available online: https://mcit.gov.eg/Upcont/Documents/Publications_2142021000_ICT_Indicators_Quarterly_Bulletin_Q4%202020.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2022).

- Saied, S.M.; Elsabagh, H.M.; El-Afandy, A.M. Internet and Facebook addiction among Egyptian and Malaysian medical students: A comparative study, Tanta University, Egypt. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2016, 3, 1288–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, R.; Mohammed, N.; Aly, H. Internet addiction among medical students of Sohag University, Egypt. J. Egypt. Public Health Assoc. 2017, 92, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araby, E.M.; Abd-El-Raouf, M.S.; Eltaher, S.M. Does the nature of the study affect internet use and addiction? Comparative-study in Benha University, Egypt. Syst. Rev. Pharm. 2020, 11, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oweikpodor, V.G.; Onafowope, M.A. Lecturers’ perception of factors responsible for students’ lecture attendance in colleges of education in Delta State, Nigeria. Eur. J. Educ. Stud. 2022, 9, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thatcher, A.; Fridjhon, P.; Cockcroft, K. The relationship between lecture attendance and academic performance in an undergraduate psychology class. S. Afr. J. Psychol. 2007, 37, 656–660. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC98438 (accessed on 14 December 2022). [CrossRef]

- Andrietti, V. Does lecture attendance affect academic performance? Panel data evidence for introductory macroeconomics. Int. Rev. Econ. Educ. 2014, 15, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goode, E.; Nieuwoudt, J.; Roche, T. Does online engagement matter? The impact of interactive learning modules and synchronous class attendance on student achievement in an immersive delivery model. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 2022, 38, 76–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO Institute for Statistics. International Standard Classification of Education ISCED 2011; UNESCO-UIS: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2012; Available online: http://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/international-standard-classification-of-educationisced-2011-en.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- Dusek, G.; Yurova, Y.; Ruppel, C. Using social media and targeted snowball sampling to survey a hard-to-reach population: A case study. Int. J. Dr. Stud. 2015, 10, 279–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, M. Nonprobability sampling. In Encyclopedia of Survey Research Methods; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 523–526. [Google Scholar]

- Stratton, S. Population research: Convenience sampling strategies. Prehosp. Disaster Med. 2021, 36, 373–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruch, Y. Response rate in academic studies: A comparison analysis. Hum. Relat. 1999, 52, 421–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T.; Owens, L. Survey response rate reporting in the professional literature. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the American Association for Public Opinion Research, Nashville, TN, USA, 15–18 May 2003; pp. 127–133. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).