Immersive Place-Based Attachments in Rural Australia: An Overview of an Allied Health Program and Its Outcomes

Abstract

1. Introduction

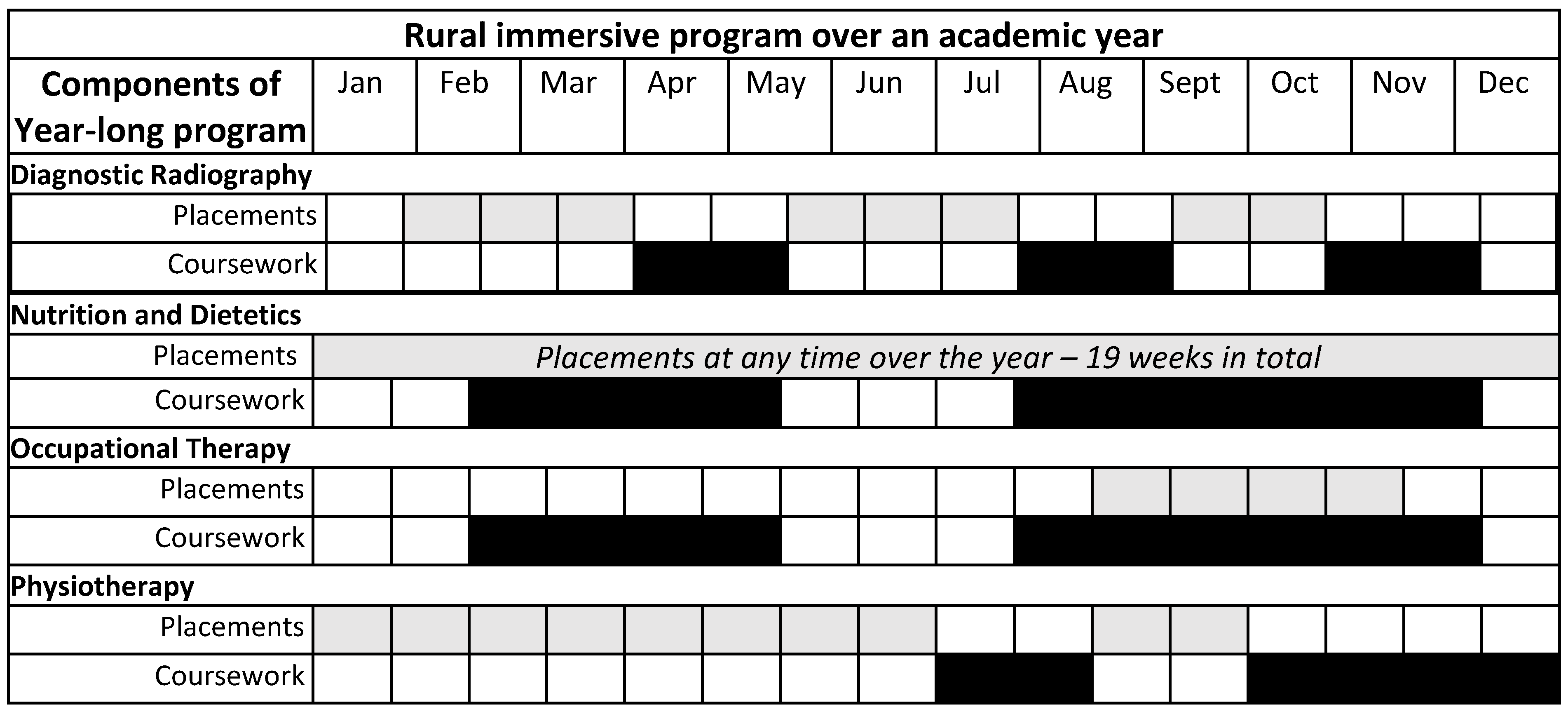

Rural Immersive Attachment Program

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.1.1. Rural Immersion Attachment Program Data

2.1.2. Student Follow Up Study Data

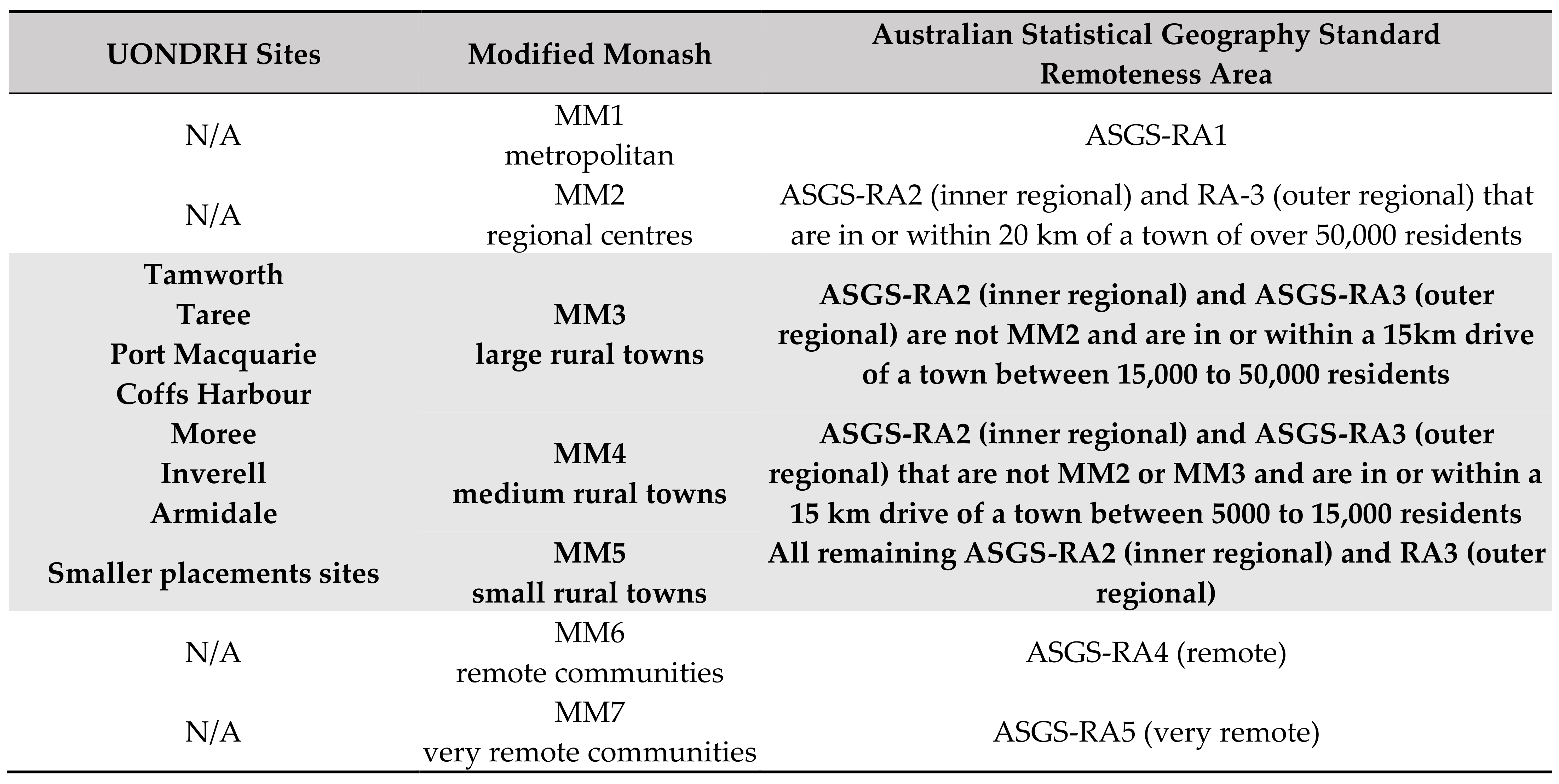

2.2. Setting and Participants

2.2.1. Recruitment and Sampling

2.2.2. Data Collection

2.2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Academic Staffing and Year-Long Student Attachment Data

3.2. Data from End of Placement Surveys

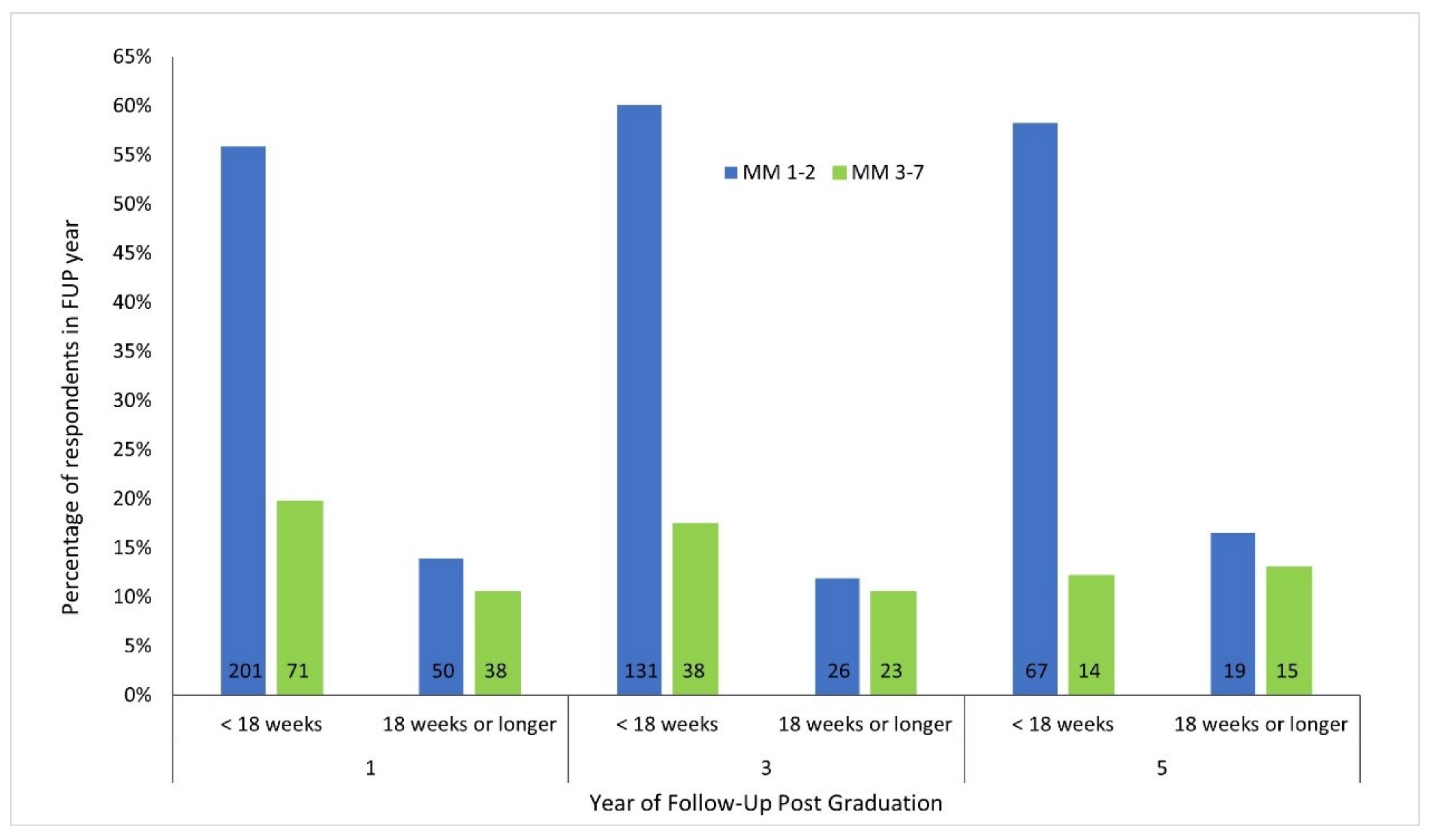

3.3. Longitudinal Follow-Up Study Data from Graduate Follow-Up Surveys at 1, 3 and 5 Years

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Williamson, T.W.; Hughes, S.; Flick, J.E.; Burnett, K.; Bradford, J.L.; Ross, L.L. Clinical Experiences: Navigating the Intricacies of Student Placement Requirements. J. Allied Health 2018, 47, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McAllister, L.; Nagarajan, S.V. Accreditation requirements in allied health education: Strengths, weaknesses and missed opportunities. J. Teach. Learn. Grad. Employab. 2015, 6, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, A.; Nancarrow, S.; Cosgrave, C.; Griffith, A.; Memery, R. What works, why and how? A scoping review and logic model of rural clinical placements for allied health students. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Happell, B.; Gaskin, C.J. The attitudes of undergraduate nursing students towards mental health nursing: A systematic review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2012, 22, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, G.J.; Brodie, D.A.; Andrews, J.P.; Wong, J.; Thomas, B.G. Place(ment) matters: Students’ clinical experiences and their preferences for first employers. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2005, 52, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCall, L.; Wray, N.; McKenna, L. Influence of clinical placement on undergraduate midwifery students' career intentions. Midwifery 2009, 25, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, K.; Waller, S.; Fisher, K.; Farthing, A.; McAnnally, K.; Russell, D.; Smith, T.; Maybery, D.; McGrail, M.; Brown, L.; et al. “Heck Yes”—Understanding the Decision to Relocate Rural amongst Urban Nursing and Allied Health Students and Recent Graduates; Monash University Department of Rural Health: Newborough, Australia, 2016; p. 138. [Google Scholar]

- Dussault, G.; Franceschini, M.C. Not enough there, too many here: Understanding geographical imbalances in the distribution of the health workforce. Hum. Resour. Health 2006, 4, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. Rural Health Multidisciplinary Training Program. 2022. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/initiatives-and-programs/rhmt. (accessed on 8 November 2022).

- O’Sullivan, B.; McGrail, M.; Russell, D.; Walker, J.; Chambers, H.; Major, L.; Langham, R. Duration and setting of rural immersion during the medical degree relates to rural work outcomes. Med. Educ. 2018, 52, 803–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinowitz, H.K.; Diamond, J.J.; Markham, F.W.; Hazelwood, C.E. A program to increase the number of family physicians in rural and underserved areas: Imapct after 22 years. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1999, 281, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogenbirk, J.; Timothy, P.; French, M.; Strasser, R.; Pong, R.; Cervin, C.; Graves, L. Milestones on the social accountability journey: Family medicine practice locations of Northern Ontario School of Medicine graduates. Can. Fam. Physician 2016, 62, e138–e145. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhill, J.A.; Walker, J.; Playford, D. Outcomes of Australian rural clinical schools: A decade of success building the rural medical workforce through education and training continuum. Rural. Remote Health 2015, 15, 2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, B.; McGrail, M.; Russell, D.; Chambers, H.; Major, L. A review of characteristics and outcomes of Australia’s undergraduate medical education rural immersion programs. Hum. Resour. Health 2018, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, J.; Kenny, A.; McKinstry, C.; Huysmans, R.D. A scoping review of the association between rural medical education and rural practice location. Hum. Resour. Health 2015, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolley, T.; Gupta, T.; Bellei, M. Predictors of remote practice location in the first seven cohorts of James Cook University MBBS graduates. Rural. Remote Health 2017, 17, 3992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, K.; Depczynski, J.; Smith, T.; Mitchell, E.; Wakely, L.; Brown, L.; Waller, S.; Drumm, D.; Versace, V.; Fisher, K.; et al. Destinations of nursing and allied health graduates from two Australian universities: A data linkage study to inform rural placement models. Aust. J. Rural. Health 2021, 2, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, Y.; Kazmi, S.; King, S.; Solomon, S.; Knight, S. Positive placement experience and future rural practice intention: Findings from a repeated cross-sectional study. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2018, 11, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Playford, D.; Moran, M.; Thompson, S. Factors associated with rural work for nursing and allied health graduates 15-17 years after an undergraduate rural placement through the University Department of Rural Health program. Rural. Remote Health 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, N.; Farthing, A.; Lenthall, S.; Moore, L.; Anderson, J.; Witt, S.; Rissel, C. Workplace locations of allied health and nursing graduates who undertook a placement in the Northern Territory of Australia from 2016 to 2019: An observational cohort study. Aust. J. Rural. Health 2021, 29, 948–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.J.; Smith, T.; Wakely, L.; Little, A.; Wolfgang, R.; Burrows, J. Preparing graduates to meet the allied health workforce needs in rural Australia: Short-term outcomes from a longitudinal study. Educ. Sci. 2017, 7, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Playford, D.; Larson, A.; Wheatland, B. Going country: Rural student placement factors associated with future rural employment in nursing and allied health. Aust. J. Rural. Health 2006, 14, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.; Sutton, K.; Beauchamp, A.; Depczynski, J.; Brown, L.; Fisher, K.; Waller, S.; Wakely, L.; Maybery, D.; Versace, V. Profile and rural exposure for nursing and allied health students at two Australian Universities: A retrospective cohort study. Aust. J. Rural. Health 2020, 29, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- KBC Australia; Battye, K.; Sefton, C.; Thomas, J.; Smith, J.; Springer, S.; Skinner, I.; Callander, E.; Butler, S.; Wilkins, R.; et al. Independent Evaluation of the Rural Health Multidisciplinary Training Program; KBC Australia: Orange, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, L.; Smith, T.; Wakely, L.; Wolfgang, R.; Little, A.; Burrows, J. Longitudinal tracking of workplace outcomes for undergraduate allied health students undertaking placements in Rural Australia. J. Allied Health 2017, 46, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Smith, A.; Brown, L.; Cooper, R. A multidisciplinary model of rural allied health clinical-academic practice. J. Allied Health 2009, 38, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wolfgang, R.; Wakely, L.; Smith, T.; Burrows, J.; Little, A.; Brown, L.J. Immersive placement experiences promote rural intent in allied health students of urban and rural origin. J. Mutlidiscip. Healthc. 2019, 12, 699–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Government Department of Health. Modified Monash Model. 2020. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2020/07/modified-monash-model-fact-sheet.pdf. (accessed on 26 September 2022).

- Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. Australian Statistical Geography Standard—Remoteness Structure. 2021. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/statistical-geography/remoteness-structure. (accessed on 14 December 2021).

| Location | Allied Health Disciplines | Full-Time Equivalents |

|---|---|---|

| Locations with rural immersion attachment program | ||

| Coffs Harbour a | Diagnostic Radiography Dietetics Occupational Therapy Physiotherapy Speech Pathology | 3.2 |

| Tamworth a | Diagnostic Radiography Dietetics Occupational Therapy Physiotherapy Speech Pathology c | 4.3 |

| Taree a,b | Allied Health (Physiotherapy) d (Speech Pathology) d | 0.8 |

| Port Macquarie a | Dietetics Occupational Therapy Physiotherapy Radiation Therapy Speech Pathology | 3.2 |

| Locations with short-term placements and academic support | ||

| Armidale | Dietetics Physiotherapy Speech Pathology | 1.2 |

| Inverell | Allied Health (Physiotherapy) d | 0.4 |

| Moree | Allied Health (Dietetics) d | 0.4 |

| Total | 10.7 | |

| Year | Dietetics | Physiotherapy | Occupational Therapy | Medical Radiation Science b | Totals (Year-Long) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 2 | - | - | 5 | 7 |

| 2010 | 4 | 1 | - | 4 | 9 |

| 2011 | 6 | 3 | - | 3 | 12 |

| 2012 | 2 | 1 | - | 4 | 7 |

| 2013 | 3 | 3, 1 semester long | - | 13 | 19 |

| 2014 | 5 | 9 | - | 15 | 29 |

| 2015 | 3 | 6 | - | 5 | 14 |

| 2016 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 8 | 27 |

| 2017 | 8, 3 semester long | 10 | 4 | 6 | 28 |

| 2018 | 11, 1 semester long | 7, 3 semester long | 7 | 4 | 29 |

| 2019 | 7, 3 semester long | 22 | 7 | 5 | 41 |

| 2020 c | 8, 1 semester long | 26, 1 semester long | 3 | 2 | 39 |

| 2021 | 13, 4 semester long | 21 | 9 | 11, 5 semester long | 54 |

| Totals | 78 12 semester long | 116 5 semester long | 32 | 85 5 semester long | 311 22 semester long |

| Placement/Attachment Length | Rural Background a | n = | Rural Practice Intention b Mean Rating (SD) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | ||||

| Less than 18 weeks | None or less than 1 year | 224 | 3.02 (1.114) | 2.20 (0.908) | <0.001 |

| 1 year or more | 195 | 2.10 (1.001) | 1.87 (0.797) | <0.001 | |

| 18 weeks or longer | None or less than 1 year | 49 | 2.53 (1.043) | 1.73 (0.785) | <0.001 |

| 1 year or more | 85 | 1.81 (1.018) | 1.72 (0.854) | 0.251 | |

| Year a | Employment Location | Australian-Based Location by Remoteness Classification | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employed in Australia | Employed Overseas | Not Employed in Health Profession | Invalid or No Answer | Total | Rural RA 2–5; MM 3–7 n = (%) | Metro RA 1; MM 1–2 n = (%) | |

| 1 | 360 | 0 | 34 | 35 | 429 | 145 (40.3); 109 (30.3) | 215 (59.7); 251 (69.7) |

| 3 | 218 | 10 | 21 | 14 | 263 | 87 (39.9); 61 (28.0) | 131 (60.1); 157 (72.0%) |

| 5 | 115 | 7 | 25 | 8 | 155 | 42 (36.5); 29 (25.2) | 73 (63.5); 86 (74.8) |

| Year | n = | Variable | Nagelkerke R Square | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 360 | Rural Background b | 0.106 | 2.884 (1.774–4.690) | <0.001 |

| Placement/Attachment of 18 weeks or longer | 2.018 (1.204–3.382) | 0.008 | |||

| 3 | 218 a | Rural Background b | 0.203 | 4.499 (2.219–9.125) | <0.001 |

| Placement/Attachment of 18 weeks or longer | 2.727 (1.325–5.614) | 0.006 | |||

| 5 | 115 | Rural Background b | 0.225 | 5.734 (1.770–15.580) | 0.004 |

| Placement/Attachment of 18 weeks or longer | 2.335 (0.902–6.042) | 0.080 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brown, L.J.; Wakely, L.; Little, A.; Heaney, S.; Cooper, E.; Wakely, K.; May, J.; Burrows, J.M. Immersive Place-Based Attachments in Rural Australia: An Overview of an Allied Health Program and Its Outcomes. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13010002

Brown LJ, Wakely L, Little A, Heaney S, Cooper E, Wakely K, May J, Burrows JM. Immersive Place-Based Attachments in Rural Australia: An Overview of an Allied Health Program and Its Outcomes. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrown, Leanne J., Luke Wakely, Alexandra Little, Susan Heaney, Emma Cooper, Katrina Wakely, Jennifer May, and Julie M. Burrows. 2023. "Immersive Place-Based Attachments in Rural Australia: An Overview of an Allied Health Program and Its Outcomes" Education Sciences 13, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13010002

APA StyleBrown, L. J., Wakely, L., Little, A., Heaney, S., Cooper, E., Wakely, K., May, J., & Burrows, J. M. (2023). Immersive Place-Based Attachments in Rural Australia: An Overview of an Allied Health Program and Its Outcomes. Education Sciences, 13(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13010002