Are Veterinary Students Using Technologies and Online Learning Resources for Didactic Training? A Mini-Meta Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Systematic Review

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

- a.

- All research articles that reported the use of online resources and electronic devices by veterinary students for study purposes only.

- b.

- Cross-sectional studies that assessed as a primary or secondary outcome the use of electronic devices to access the learning environment and the usage of learning resources in any format.

- c.

- Respondents were veterinary students from undergraduate to residency level.

- d.

- Studies that included surveys or research-based projects.

- e.

- Written in English language only.

- f.

- Published from 1 January 2012 to 10 June 2022.

- g.

- Peer-reviewed only.The exclusion criteria were studies in which the use of online resources and electronic devices were not used for educational purposes. Commentaries, letters to editor, editorials, expert opinions, original articles without sufficient details, reviews, and conference abstracts or proceedings were also excluded.

2.3. Data Sources and Search Strategy

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Terminology

- -

- Non-portable electronic devices (e.g., desktop computers) can be defined as any type of media device designed for regular use at a single location [30].

- -

- Portable electronic devices are defined as any media device type with capacities to store, record, transmit text/videos/audios. Examples of such devices are smartphones, laptops, tablets, etc. These devices offer features of portability, which desktop computers cannot offer [31].

- -

- Textbooks are defined as books used as a standard work for studying a particular subject [32].

- -

- E-Books or electronic books are electronic versions of printed books that can be read on computers or handheld devices which are designed specifically for them [33].

- -

- Educational websites are defined as appropriately designed and developed websites which hold the potential to provide to students valuable educational content [34].

- -

- Educational applications are defined as educational software which are specifically designed and developed for teaching and learning purposes [35].

- -

- Research papers are defined as manuscripts that represent original works of scientific research or studies [36].

- -

- YouTube videos are defined as visual content shared through a channel called YouTube. Due to its open-access nature, content can reach a broad audience, and it is often used in education as a platform for sharing educational videos [18].

- -

- Social media platforms are defined as any sites which combine internet- based technologies and mobile applications and allow users to share content and/or participate in social networking [37].

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

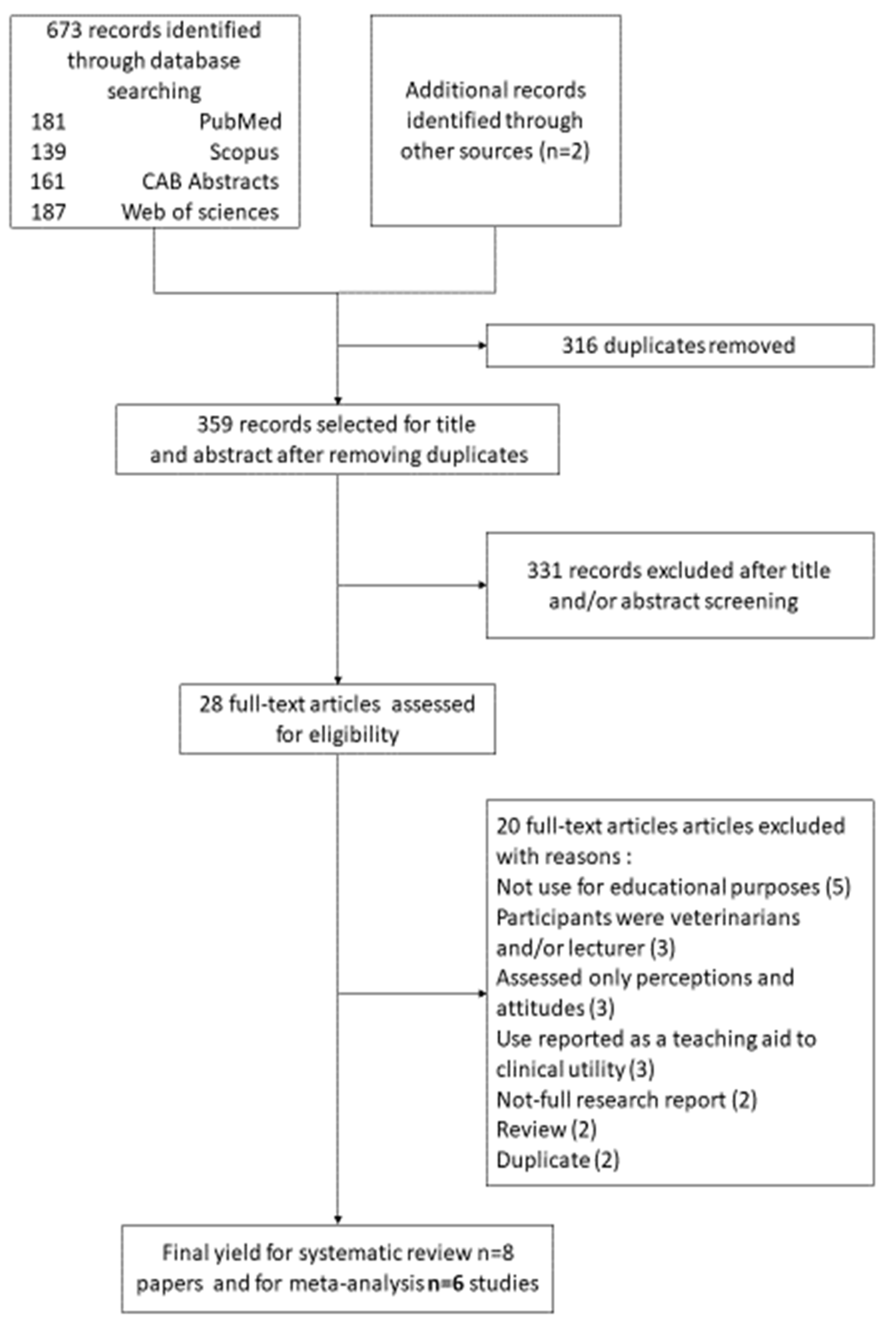

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Study Results and Meta-Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shahzad, A.; Hassan, R.; Aremu, A.Y.; Hussain, A.; Lodhi, R.N. Effects of COVID-19 in E-Learning on Higher Education Institution Students: The Group Comparison between Male and Female. Qual. Quant. 2021, 55, 805–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lassoued, Z.; Alhendawi, M.; Bashitialshaaer, R. An Exploratory Study of the Obstacles for Achieving Quality in Distance Learning during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gledhill, L.; Dale, V.H.M.; Powney, S.; Gaitskell-Phillips, G.H.L.; Short, N.R.M. An International Survey of Veterinary Students to Assess Their Use of Online Learning Resources. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 2017, 44, 692–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liatis, T.; Patel, B.; Huang, M.; Buren, L.; Kotsadam, G. Student Involvement in Global Veterinary Education and Curricula: 7 Years of Progress (2013–2019). J. Vet. Med. Educ. 2020, 47, 379–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dooley, L.M.; Frankland, S.; Boller, E.; Tudor, E. Implementing the Flipped Classroom in a Veterinary Pre-Clinical Science Course: Student Engagement, Performance, and Satisfaction. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 2018, 45, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baillie, S.; Kinnison, T.; Forrest, N.; Dale, V.H.M.; Ehlers, J.P.; Koch, M.; Mándoki, M.; Ciobotaru, E.; De Groot, E.; Boerboom, T.B.B.; et al. Developing an Online Professional Network for Veterinary Education: The NOVICE Project. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 2011, 38, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Veterinary Students’ Association. Available online: https://www.ivsa.org/ (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- VET Talks—One World, One Health|International Veterinary Students’ Association (IVSA). Available online: https://www.afrivip.org/ivsa_subdomain/resources/vet-talks-one-world-one-health/ (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- WikiVet English. Available online: https://en.wikivet.net/Veterinary_Education_Online (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- Baillie, S.; Rhind, S.; MacKay, J.; Murray, L.; Mossop, L. The VetEd Conference: Evolution of an Educational Community of Practice. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 2021, 49, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKay, J.R.D.; Langford, F.; Waran, N. Massive Open Online Courses as a Tool for Global Animal Welfare Education. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 2016, 43, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Root Kustritz, M.V. Canine Theriogenology for Dog Enthusiasts: Teaching Methodology and Outcomes in a Massive Open Online Course (MOOC). J. Vet. Med. Educ. 2014, 41, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, J.; Hughes, K.; Steer, L.; Das Gupta, M.; Boyd, S.; Bell, C.; Rhind, S. Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) as a Window into the Veterinary Profession. Vet. Rec. 2017, 180, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Home—VetMedAcademy. Available online: https://vetmedacademy.org/ (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- El Idrissi, A.H.; Larfaoui, F.; Dhingra, M.; Johnson, A.; Pinto, J.; Sumption, K. Digital Technologies and Implications for Veterinary Services. Rev. Sci. Tech. 2021, 40, 455–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- How Technology Is Transforming Veterinary Education—Today’s Veterinary Practice. Available online: https://todaysveterinarypractice.com/technology/how-technology-is-transforming-veterinary-education/ (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- Kasch, C.; Haimerl, P.; Arlt, S.; Heuwieser, W. The Use of Mobile Devices and Online Services by German Veterinary Students. Vet. Evid. 2016, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Müller, L.R.; Tipold, A.; Ehlers, J.P.; Schaper, E. TiHoVideos: Veterinary Students’ Utilization of Instructional Videos on Clinical Skills. BMC Vet. Res. 2019, 15, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdy, M.A.A. The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on the Academic Performance of Veterinary Medical Students. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 594261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limniou, M.; Varga-Atkins, T.; Hands, C.; Elshamaa, M. Learning, Student Digital Capabilities and Academic Performance over the COVID-19 Pandemic. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdy, M.A.A.; Ewaida, Z.M. Evaluation of the Emergency Remote Learning of Veterinary Anatomy During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Global Students’ Perspectives. Front. Educ. 2022, 6, 728365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdy, M.A.A.; Sayed, R.K.A. Evaluation of the Online Learning of Veterinary Anatomy Education during the COVID-19 Pandemic Lockdown in Egypt: Students’ Perceptions. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2022, 15, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamage, S.H.P.W.; Ayres, J.R.; Behrend, M.B. A Systematic Review on Trends in Using Moodle for Teaching and Learning. Int. J. STEM Educ. 2022, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones-Hall, Y.L.; Skelton, J.M.; Adams, L.G. Implementing Digital Pathology into Veterinary Academics and Research. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 2021, e20210068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washburn, S.E.; Cook, A.K.; Tayce, J.D. Replacing a Veterinary Physiology Endocrinology Lecture with a Blended Learning Approach Using an Everyday Analogy. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 2022, 49, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, J.E. Writing for Wikipedia: An Exercise in Microbiology, Writing, Research, Communication, and Public Service. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 2021, e20210099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boller, E.; Courtman, N.; Chiavaroli, N.; Beck, C. Design and Delivery of the Clinical Integrative Puzzle as a Collaborative Learningtool. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 2021, 48, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avignon, D.; Farnir, F.; Iatridou, D.; Iwersen, M.; Lekeux, P.; Moser, V.; Saunders, J.; Schwarz, T.; Sternberg-Lewerin, S.; Weller, R. Report of the Eccvt Expert Working Group on the Impact of Digital Technologies & Artificial Intelligence in Veterinary Education and Practice. pp. 1–8. 2020. Available online: https://www.eaeve.org/fileadmin/downloads/eccvt/DTAI_WG_final_report_ECCVT_adopted.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2022).

- Grindlay, D.J.C.; Brennan, M.L.; Dean, R.S. Searching the Veterinary Literature: A Comparison of the Coverage of Veterinary Journals by Nine Bibliographic Databases. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 2012, 39, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portable or Non-Portable Computer? By Sahil Jassal. Available online: https://prezi.com/pgomvu4ihfuw/portable-or-non-portable-computer/ (accessed on 28 June 2022).

- Chinnery, G.M. Going to the MALL: Mobile Assisted Language Learning. Lang. Learn. Technol. 2006, 10, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Textbook, n.: Oxford English Dictionary. Available online: https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/200006?redirectedFrom=textbook#eid (accessed on 28 June 2022).

- Vassiliou, M.; Rowley, J. Progressing the Definition of “E-book”. Libr. Hi Tech 2008, 26, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, C.R.; Kerr, B.R.; Frohna, J.G.; Moreno, M.A.; Zarvan, S.J.; McCormick, D.P. The Development, Implementation, and Evaluation of an Acute Otitis Media Education Website. Acad. Pediatr. 2021, 21, 1099–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gladman, T.; Tylee, G.; Gallagher, S.; Mair, J.; Rennie, S.C.; Grainger, R. A Tool for Rating the Value of Health Education Mobile Apps to Enhance Student Learning (MARuL): Development and Usability Study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2020, 8, e18015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Research Paper: Definition, Structure, Characteristics, and Types. Available online: https://wr1ter.com/research-paper (accessed on 28 June 2022).

- Aichner, T.; Grü, M.; Maurer, O.; Jegeni, D. Twenty-Five Years of Social Media: A Review of Social Media Applications and Definitions from 1994 to 2019. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2021, 4, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollesel, M.; Tassinari, M.; Frabetti, A.; Fornasini, D.; Cavallini, D. Effect of Does Parity Order on Litter Homogeneity Parameters. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2020, 19, 1188–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekong, P.S.; Sanderson, M.W.; Cernicchiaro, N. Prevalence and Concentration of Escherichia Coli O157 in Different Seasons and Cattle Types Processed in North America: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Published Research. Prev. Vet. Med. 2015, 121, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring Inconsistency in Meta-Analyses. Br. Med. J. 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saadeh, K.; Henderson, V.; Paramasivam, S.J.; Jeevaratnam, K. To What Extent Do Preclinical Veterinary Students in the UK Utilize Online Resources to Study Physiology. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 2021, 45, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saadeh, K.; Henderson, V.; Julita Paramasivam, S.; Jeevaratnam, K. Use of Online Resources to Study Cardiology by Clinical Veterinary Students in the United Kingdom. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 2022, 49, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurell, J.A.C.; Diamond, N.A.; Buie, B.; Grant, D.; Pijanowski, G.J. Tablet Computers in the Veterinary Curriculum. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 2005, 32, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Rush, B.R.; Wilkerson, M.; van der Merwe, D. Exploring the Use of Tablet PCs in Veterinary Medical Education: Opportunity or Obstacle? J. Vet. Med. Educ. 2014, 41, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Emran, M.; Elsherif, H.M.; Shaalan, K. Investigating Attitudes towards the Use of Mobile Learning in Higher Education. Comput. Human Behav. 2016, 56, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, Y.T.; Chang, K.E.; Liu, T.C. The Effects of Integrating Mobile Devices with Teaching and Learning on Students’ Learning Performance: A Meta-Analysis and Research Synthesis. Comput. Educ. 2016, 94, 252–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton, J. Open Educational Resources and College Textbook Choices: A Review of Research on Efficacy and Perceptions. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2016, 64, 573–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, B.C.; Hartle, D.Y.; Creevy, K.E. The Educational Resource Preferences and Information-Seeking Behaviors of Veterinary Medical Students and Practitioners. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 2019, 46, 470–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, E.W. Why Undergraduate Students Choose to Use E-Books. J. Librariansh. Inf. Sci. 2014, 46, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, H.R.; Nicholas, D.; Rowlands, I. Scholarly E-Books: The Views of 16,000 Academics: Results from the JISC National E-Book Observatory. Aslib Proc. New Inf. Perspect. 2009, 61, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelburne, W.A. E-Book Usage in an Academic Library: User Attitudes and Behaviors. Libr. Collect. Acquis. Tech. Serv. 2009, 33, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanov, K.; Aarnio, M. A Survey of the Use of Electronic Scientific Information Resources among Medical and Dental Students. BMC Med. Educ. 2006, 6, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klimek, J. Teaching Scientific Information Literacy Skills to Veterinary Students: The Missing Link. 2014. Available online: http://www.aavmc.org/assets/data-new/files/AnnualConference/2014/PPT/Klimek.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2022).

- Eldermire, E.R.B.; Fricke, S.; Alpi, K.M.; Davies, E.; Kepsel, A.C.; Norton, H.F. Information Seeking and Evaluation: A Multi-Institutional Survey of Veterinary Students. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2019, 107, 515–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauro, D.M.; Ellis, J.A.; Lilly, J.F.; Dallaghan, G.L.B.; Jordan, S.G. Creating an Open-Access Educational Radiology Website for Medical Students: A Guide for Radiology Educators. Acad. Radiol. 2021, 28, 1631–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynter, L.; Burgess, A.; Kalman, E.; Heron, J.E.; Bleasel, J. Medical Students: What Educational Resources Are They Using? BMC Med. Educ. 2019, 19, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royal Veterinary College Enables Students to Learn from Virtual Veterinary Experiences in a New Phone App. Available online: https://www.rvc.ac.uk/vetcompass/news/royal-veterinary-college-enable-students-to-learn-from-virtual-veterinary-experiences-in-a-new-phone-app (accessed on 6 July 2022).

- Chandran, V.P.; Balakrishnan, A.; Rashid, M.; Pai Kulyadi, G.; Khan, S.; Devi, E.S.; Nair, S.; Thunga, G. Mobile Applications in Medical Education: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0265927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ødegaard, N.B.; Myrhaug, H.T.; Dahl-Michelsen, T.; Røe, Y. Digital Learning Designs in Physiotherapy Education: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshier, A.L.; Foster, N.; Jones, M.A. Veterinary Students’ Usage and Perception of Video Teaching Resources. BMC Med. Educ. 2011, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiellet, C.A.B.; Pereira, A.G.; Reategui, E.B.; Lima, J.V.; Chambel, T. Design and Evaluation of a Hypervideo Environment to Support Veterinary Surgery Learning. In Proceedings of the 21st ACM Conference on Hypertext and Hypermedia, Toronto, ON, Canada, 13–16 June 2010; pp. 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guraya, S.Y. The Usage of Social Networking Sites by Medical Students for Educational Purposes: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. N. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2016, 8, 268–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, M.; Kinnison, T.; Mossop, L. Teaching Tip: Developing an Intercollegiate Twitter Forum to Improve Student Exam Study and Digital Professionalism. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 2016, 43, 282–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinnison, T.; Whiting, M.; Magnier, K.; Mossop, L. Evaluating #VetFinals: Can Twitter Help Students Prepare for Final Examinations? Med. Teach. 2017, 39, 436–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kivunja, C. Innovative Methodologies for 21st Century Learning, Teaching and Assessment: A Convenience Sampling Investigation into the Use of Social Media Technologies in Higher Education. Int. J. High. Educ. 2015, 4, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ansari, J.A.N.; Khan, N.A. Exploring the Role of Social Media in Collaborative Learning the New Domain of Learning. Smart Learn. Environ. 2020, 7, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rahmi, W.M.; Othman, M.S.; Musa, M.A. The Improvement of Students’ Academic Performance by Using Social Media through Collaborative Learning in Malaysian Higher Education. Asian Soc. Sci. 2014, 10, 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Search Strategy Item | Search Strategy Details |

|---|---|

| String of Keywords | (education, veterinary [mh] OR veterinary, students [mh] OR veterinary, education [mh] OR “undergraduate veterinary education” OR “veterinary students” OR “veterinary student” OR “veterinary schools” OR “ veterinary school”) AND (“online learn*” OR “electronic learn*” OR “e-learn*” OR “distance learn*” OR “flipped learn*” OR “hybrid learn*” OR “blended learn*” OR “mobile learn*” OR “m-learn*” OR “digital learn*” OR “online resourc*“ OR “smartphone” OR “laptop” OR “tablet” OR “desktop” OR “computer” OR “online participation” OR “online discussion” OR ”electronic devic*” OR “digital devic*” OR “educational web*” OR “social media” OR “video” OR “multimedia” AND (measure* OR assess* OR evaluate*) |

| Searched Databases | PubMed, Web of Science, CAB Abstracts, Scopus. |

| Time Filter | From 1 January 2012 to 10 June 2022 |

| Language Filter | English |

| Study | Nr of Veterinary Students | Gender | Mean Age | UK | Europe | North America | Oceania | Asia | Africa | South America | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | F | ||||||||||

| Gledhill et al. (2017) [3] | 1070 | NS | NS | NS | 326 | 259 | 223 | 119 | 95 | 29 | 14 |

| Müller et al. (2019) [18] | 805 | NS | NS | NS | 805 | ||||||

| Mahdy (2020) [19] | 1392 | 674 | 718 | 24.10 ± 5.93 | 32 | 258 | 71 | 56 | 498 | 446 | 31 |

| Sadeeh et al. (2021) [41] | 122 | 12 | 110 | 24–26 | 122 | ||||||

| Limniou et al. (2021) [20] | 170 | 33 | 137 | NS | 170 | ||||||

| Mahdy & Ewaida (2022) [21] | 961 | 424 | 537 | 22.00 ± 3.42 | 30 | 162 | 96 | 78 | 335 | 234 | 56 |

| Mahdy & Sayed (2022) [22] | 502 | 184 | 318 | 19.07 ± 0.56 | 502 | ||||||

| Sadeeh et al. (2022) [42] | 213 | 29 | 184 | 21–23 | 213 | ||||||

| Authors | Study Design | Participants | Type of Devices and Resources Assessed | Measures | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gledhill et al. (2017) [3] | Cross-sectional (survey-based) | 1070 veterinary students | Ownership of smartphones, tablets, e –readers, laptops and desktop computers. Frequency of use of the following online resources: search engines, MOOCs, virtual worlds, open educational resources (OERs), social networking (e.g., Facebook), social videos (e.g., YouTube), instant messaging (e.g., Messenger), voice calls (e.g., Skype), video conferencing (e.g., Google Hangout), social images (e.g., Pinterest) microblogging (e.g., Twitter), social bookmarking (e.g., Del.ico.us), WikiVet, Merck, VIN, Vetstream, NOVICE. | Questionnaire | The majority of students reported using online educational veterinary resources. Ownership of smartphones was widespread (92%), and the majority of respondents (74%) indicated that the use of mobile devices was essential for their learning. Social media platforms were indicated as essential for collaborating with peers and sharing knowledge between them. The students from less-developed countries were disadvantaged by limited access to technology and networks. |

| Müller et al. (2019) [18] | Mixed-methods (survey-observational) | 835 veterinary students | Ownership of smartphones, laptops, tablets, and computers. Instructional YouTube videos prepared for clinical skill laboratories. | Questionnaire (paper-based and online survey) | Before hands-on activities in the clinical skill laboratories, students watched videos on laptops, tablets, or smartphones. Almost all students rated the instructional videos as valuable and helpful learning tools. |

| vMahdy (2020) [19] | Cross-sectional | 1392 veterinary students | Smartphones, laptops, tablets, and computers. Online classes, PDF lectures, textbooks, YouTube videos, University platforms, educational websites, educational applications, Zoom, WhatsApp groups, Google classroom, social networks, Microsoft teams, Edmodo, Skype, Google Meet, Blackboard, Web Whiteboard, Moodle, WebEx, Canvas, VIN, Edpuzzle, Edverum. | Online questionnaire | 96.7% of students reported that COVID-19 affected their academic performance. However, online instruction provided students with the opportunity for self-directed study. The most challenging aspect of online instruction was related to the hands-on sessions. Zoom was the most-used online tool, followed by WhatsApp groups and Google Classrooms. Online courses were the most preferred sources of online learning. |

| Saadeh et al. (2021) [41] | Cross-sectional | 122 veterinary students | Smartphones, laptops, tablets, and computers. Sources for physiology information: lectures, textbooks, random internet search engines, WikiVet, YouTube videos, VIN, Wikipedia, social media platforms and research papers. | Online questionnaire | Traditional resources such as lectures and textbooks were the most-preferred. 97% of students used search engines to supplement their physiology learning. 91.1% of students considered videos to be a valuable tool for their learning. 92% of students indicated that they would first search online for an answer before asking instructors. |

| Limniou et al. (2021) [20] | Cross-sectional | 170 veterinary students | Smartphones and laptops. Word software, presentation software, e-mail packages, statistics packages, spreadsheet software, virtual learning environments, web conferencing applications, video-sharing applications | Online questionnaire | Students reported their most common learning behaviors during the lockdown. Students with high levels of self-regulation and digital literacy reported that they were focused and engaged in their studies during COVID-19 lockdown. |

| Mahdy & Ewaida (2022) [21] | Cross-sectional | 961 veterinary students | Smartphones, laptops, tablets, and computers. YouTube videos, anatomy textbooks, anatomy e-books, educational websites, anatomy Facebook pages, educational applications, anatomy WhatsApp groups, anatomy Telegram channels and research papers. | Online questionnaire | 86% of respondents indicated that they were interested in studying anatomy online during the COVID-19 pandemic. 61% of students were able to understand online anatomy well using online learning resources accessed via electronic devices during the lockdown. |

| Mahdy & Sayed (2022) [22] | Cross-sectional | 502 veterinary students | Smartphones, laptops, tablets, and computers. Anatomy e-books, YouTube videos, Telegram channels, educational websites, Facebook pages, research papers, educational applications and WhatsApp groups. | Online questionnaire | The majority of students were enthusiastic about studying anatomy online during COVID-19 lockdowns. 63% of the respondents were satisfied with the provided learning materials. 66% of the students could understand anatomy through online learning and 67% reported to be comfortable with technological skills. 47% of the respondents believed that online learning of anatomy could replace face-to-face learning. |

| Saadeh et al. (2022) [42] | Cross-sectional | 213 veterinary students | Smartphones, laptops, tablets, and computers. Sources for cardiology information: lectures, textbooks, random internet search engines, WikiVet, YouTube videos, VIN, Wikipedia, social media platforms, and research papers. | Online questionnaire | The lecturer was indicated as the preferred resource and students aged 27 and above preferred recommended textbooks. However, 95.3% of students used search engines for cardiology information and 71.8% of students accessed videos at least once a week for cardiology learning. 93.4% of students indicated that they would search for answers online first rather than contacting the instructor. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Muca, E.; Cavallini, D.; Odore, R.; Baratta, M.; Bergero, D.; Valle, E. Are Veterinary Students Using Technologies and Online Learning Resources for Didactic Training? A Mini-Meta Analysis. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 573. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12080573

Muca E, Cavallini D, Odore R, Baratta M, Bergero D, Valle E. Are Veterinary Students Using Technologies and Online Learning Resources for Didactic Training? A Mini-Meta Analysis. Education Sciences. 2022; 12(8):573. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12080573

Chicago/Turabian StyleMuca, Edlira, Damiano Cavallini, Rosangela Odore, Mario Baratta, Domenico Bergero, and Emanuela Valle. 2022. "Are Veterinary Students Using Technologies and Online Learning Resources for Didactic Training? A Mini-Meta Analysis" Education Sciences 12, no. 8: 573. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12080573

APA StyleMuca, E., Cavallini, D., Odore, R., Baratta, M., Bergero, D., & Valle, E. (2022). Are Veterinary Students Using Technologies and Online Learning Resources for Didactic Training? A Mini-Meta Analysis. Education Sciences, 12(8), 573. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12080573