Can I Keep My Religious Identity and Be a Professional? Evaluating the Presence of Religious Literacy in Education, Nursing, and Social Work Professional Programs across Canada

Abstract

1. Introduction

If what was previously known as religion is recast as culture, then a majority “religion” becomes invisible in the public sphere, transformed into a matter of culture, heritage, and values. This has the effect of making minority religions’ claims to public space even more visible-for, while “ours” is culture, part of our heritage and values, theirs is “religion” and foreign.[4] (pp. 54–55)

2. Canadian Contexts

2.1. Secularization

2.2. Increased Religious Diversity

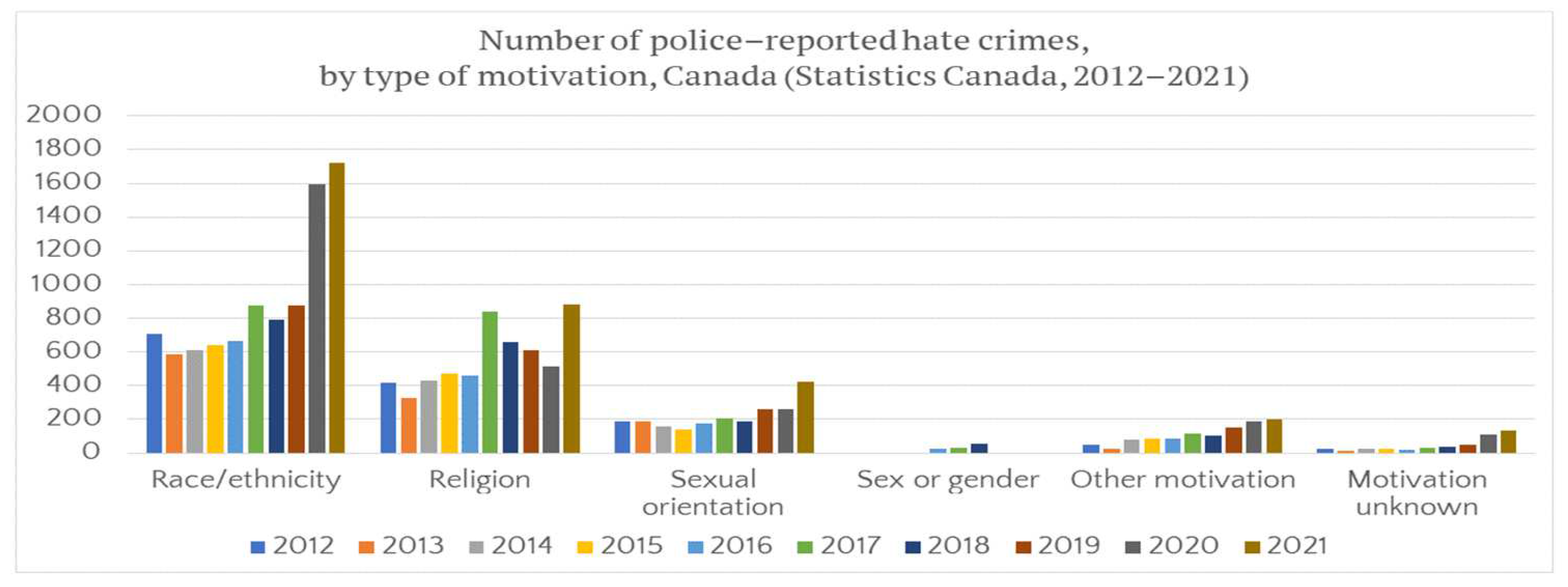

2.3. Religious Discrimination

3. Literature Review

3.1. Religious Literacy and Higher Education

3.2. Religious Literacy in Canada

- Understanding the internal diversity within worldview groups;

- Understanding the external diversity across worldview groups;

- Recognizing the influence that socio-cultural, political, and economic aspects of society have on worldview groups, and vice versa, in the past and present;

- Recognizing the need to include religious, spiritual, and non-religious worldviews in the full conversation;

- Recognizing that worldviews hold a significant personal meaning to the religious, spiritual, and non-religiously affiliated individuals. This leads us to discuss these worldviews from an individual or community’s distinct lens and not from the worldview of another person/group, and know that individuals who share the same worldview may have diverse beliefs, expressions, interpretations, and terminology to describe it based on a number of factors (such as personal circumstance, place, political context, etc.).

3.3. Intergroup Contact Theory

4. Methodology

5. Results

5.1. British Columbia

5.1.1. Bachelor of Education (BEd) at SFU

We are grateful to Indigenous Elders and Knowledge Holders for their stewardship of the lands on which our three campuses stand. By acknowledging the traditional owners of these lands, we remind ourselves of Canada’s longstanding colonial structures and systems and the need to take up our individual and collective responsibilities, humbly and respectfully, to an ongoing learning process of understanding Indigenous knowledge, histories, pedagogies, and ways of knowing and being. We also recognize the importance of attending to community through the Indigenous lens of the 4Rs (Respect, Relationships, Reciprocity, and Relevance). We do this by working together and using each opportunity we meet to gain and build trust through caring and respectful interactions. We also do this by creating inclusive learning environments that are free from racism, injustice and systems of oppression and that promote flourishing and dignity for all.[74] (p. 2)

5.1.2. Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN) at UBC

Reflection on practice to gain deeper understandings and question assumptions are essential to the art of nursing …. Examining one’s own knowledge, assumptions and “blind spots” can address negative discriminatory values and beliefs in society associated with certain cultures and groups of people …. Such relational practices shed light on stigma and other prevalent barriers to health care for people and hold potential for their correction.[82] (p. 18)

A system of comprehensive or total patient care that considers the physical, emotional, social, economic, and spiritual needs of the person; his or her response to illness; and the effect of the illness on the ability to meet selfcare needs.[82] (p. 35)

5.1.3. Bachelor of Social Work (BSW) at UVic

5.2. Alberta

5.2.1. BEd at UofL

5.2.2. BScN at UofA

- reflect on one’s own cultural beliefs and practices and their impacts on others;

- identify the influence of personal values, and beliefs;

- recognize diversity and cultural differences in others [94] (p. 7).

5.2.3. BSW at UofC

address systemic inequities and compounded disadvantages due to intersectionality of social locations, particularly for those who are members of racialized communities, Indigenous peoples, Black peoples, persons with disabilities, migrant groups (including refugees and immigrants), 2SLGBTQ+ communities, linguistic minorities as well as those who have experienced socioeconomic, caregiving, religious, political, and/or cultural barriers to their education and employment.[99] (p. 3)

5.3. Ontario

5.3.1. BEd at Queen’s University

5.3.2. BScN at UofT

- ○

- Students apply to the BScN after completing 2 years of undergraduate studies and several pre-requisite courses. The Bachelor of Nursing at the University of Toronto is an accelerated two-year program where graduates are expected to be safe, competent, and ethical nurses when providing nursing care for sick and vulnerable persons

- ○

- promoting health of individuals, families, groups and communities

- ○

- establishing and maintaining interpersonal and therapeutic relationships and partnerships

- ○

- enacting values of equity and social justice in addressing the social determinants of health

- ○

- examining, synthesizing and incorporating multiple knowledges to provide care

- ○

- collaborating as members of an interprofessional team (https://bloomberg.nursing.utoronto.ca/programs/bachelor/ accessed 8 Agust 2022)

The most common misconception—so powerful that it has taken on an aura of “fact” in the minds of many people—is the notion that it is “illegal” to ask Canadians questions about their cultural demographics, such as race, religion, physical abilities, or sexual orientation. So pervasive is this belief that to even raise the topic arouses significant negative opinion.[109] (p. 38)

5.3.3. BSW at McMaster University

As social workers, we operate in a society characterized by power imbalances that affect us all. These power imbalances are based on age, class, ethnicity, gender identity, geographic location, health, ability, race, sexual identity and income. We see personal troubles as inextricably linked to oppressive structures. We believe that social workers must be actively involved in the understanding and transformation of injustices in social institutions and in the struggles of people to maximize control over their own lives.[112]

College members do not discriminate against anyone based on race, ethnicity, language, religion, marital status, gender, sexual orientation, age, disability, economic status, political affiliation or national origin.[113]

6. Discussion

6.1. Observations

6.2. CCRL Programs

6.2.1. In Education

6.2.2. In Nursing

6.2.3. In Social Work

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alberta Education. Social Studies Kindergarten to Grade 12. 2005. Available online: https://education.alberta.ca/media/3273004/social-studies-k-6-pos.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Bramadat, P.; Seljak, D. (Eds.) Religion and Ethnicity in Canada; Pearson Education Canada Inc.: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2005; ISBN 9780321248411. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, D.L. Overcoming Religious Illiteracy: A Cultural Studies Approach to the Study of Religion in Secondary Education; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2007; ISBN 9781403963499. [Google Scholar]

- Beaman, L.G. Between the public and the private: Governing religious expression. In Religion in the Public Sphere: Canadian Case Studies; Lefebvre, S., Beaman, L.G., Eds.; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2014; pp. 44–65. ISBN 978-1442626300. [Google Scholar]

- Choquette, R. Canada’s Religions; University of Ottawa Press: Ottawa, QC, Canada, 2004; ISBN 9780776605579. [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald, A.F. Dalhousie’s Hundred Years: The romance of a little college whose spirit has fertilized a nation from ocean to ocean. Maclean’s. 1929. Available online: https://archive.macleans.ca/article/1929/4/1/dalhousies-hundred-years (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Bramadat, P.; Seljak, D. Charting the new terrain: Christianity and ethnicity in Canada. In Christianity and Ethnicity in Canada; Bramadat, P., Seljak, D., Eds.; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2008; pp. 3–48. ISBN 9780802095848. [Google Scholar]

- Kell, G. Faith institutions at U of T. The Innis Herald. 2017. Available online: http://theinnisherald.com/faith-institutions-at-u-of-t (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Gauvreau, M. The Evangelical Century: College and Creed in English Canada from the Great Revival to the Great Depression; McGill-Queen’s University Press: Montreal, QC, Canada, 1991; ISBN 0773507698. [Google Scholar]

- Seljak, D. The study of religion and the Canadian social order. Stud. Relig. 2022, 51, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramadat, P. Beyond Christian Canada: Religion and ethnicity in a multicultural society. In Religion and Ethnicity in Canada; Bramadat, P., Seljak, D., Eds.; Pearson Education Canada Inc.: North York, ON, Canada, 2005; pp. 1–29. ISBN 9780321248411. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson, G.M.; Dolmage, W.R. Education, religion, and the courts in Ontario. Can. J. Educ. 1996, 21, 363–383. Available online: https://journals.sfu.ca/cje/index.php/cje-rce/article/download/2735/2039/10021 (accessed on 25 July 2022). [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sweet, L. God in the Classroom: The Controversial Issue of Religion in Canada’s Schools; McClelland & Stewart: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1997; ISBN 077108319X. [Google Scholar]

- Seljak, D. Education, multiculturalism, and religion. In Religion and Ethnicity in Canada; Bramadat, P., Seljak, D., Eds.; Pearson Education Canada Inc.: North York, ON, Canada, 2005; pp. 178–200. ISBN 9780321248411. [Google Scholar]

- Bascaramurty, C.; Alphonso, C. A community divided. The Globe and Mail. 2017. Available online: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/toronto/a-community-divided-the-fight-over-canadian-values-threatens-to-boil-over-inpeel/article34852452/ (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Khan, M. When does free speech become offensive speech? Teaching controversial issues in classrooms. Curric. Teach. Dialogue 2019, 21, 35–50. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, J.; Rutty, C.; Villeneuve, M. Canadian Nurses Association: One Hundred Years of Service; Canadian Nurses Association: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2008; Available online: https://www.cna-aiic.ca/HigherLogic/System/DownloadDocumentFile.ashx?DocumentFileKey=33c38733-a507-92c2-d776-84f7b72f3dea&forceDialog=0 (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Griffith, K.J. The Religious Aspects of Nursing Care. 2009. Available online: https://nursing.ubc.ca/sites/nursing.ubc.ca/files/documents/ReligiousAspectsofNursingCareEEdition.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Stephany, K. The Ethic of Care: A Moral Compass for Canadian Nursing Practice; Revised Ebook; Bentham Books: Sharjah, UAE, 2020; Available online: https://ezproxy.aekc.talonline.ca/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=e000xna&AN=2391048&site=ehost-live&ebv=EB&ppid=pp_TITLE (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Graham, J.R.; Coholic, D.; Coates, J. Spirituality as a guiding construct in the development of Canadian social work: Past and present considerations. Crit. Soc. Work. 2006, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Religiosity in Canada and Its Evolution from 1985 to 2019. Insights on Canadian Society, Catalogue no. 75-006-X. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/75-006-x/2021001/article/00010-eng.pdf?st=oVlEQ-H9 (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Canada Across the Religious Spectrum: A Portrait of the Nation’s Inter-Faith Perspectives During Holy Week. Available online: https://angusreid.org/canada-religion-interfaith-holy-week/ (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Religiosity in Canada and Its Evolution from 1985 to 2019. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-627-m/11-627-m2021079-eng.htm (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Focus on Geography Series, 2016 Census. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 98-404-X2016001. Ottawa, Ontario. Data Products, 2016 Census. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/as-sa/fogs-spg/Facts-can-eng.cfm?Lang=Eng&GK=CAN&GC=01&TOPIC=7 (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Religious Freedom in Canada: Perspectives from First and Second-Generation Canadians. Available online: https://angusreid.org/religious-freedom-in-canada-immigrants/ (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20200506065356/http://trc.ca/assets/pdf/Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- National Household Survey: Aboriginal Peoples. Response Mobility and the Growth of the Aboriginal Identity Population, 2006–2011 and 2011–2016. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/99-011-x/99-011-x2019002-eng.htm (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Indigenous Population in Canada—Projections to 2041. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-627-m/11-627-m2021066-eng.htm (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Dinham, A. Religious literacy and welfare. In Religious Literacy in Policy and Practice; Dinham, A., Francis, M., Eds.; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2015; pp. 101–111. ISBN 9781447316657. [Google Scholar]

- Beaman, L.G. Deep Equality in an Era of Religious Diversity; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017; ISBN 9780198803485. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, K. Photographer Draws Attention to Islamophobia in Edmonton through Photo Series. Global News. 2022. Available online: https://globalnews.ca/news/8590131/photographer-draws-attention-to-islamophobia-in-edmonton-through-photo-series/ (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- The Centre for Civic Religious Literacy. Available online: https://ccrl-clrc.ca/ (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Police-Reported Crime Statistics in Canada. 2021. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/85-002-x/2022001/article/00013-eng.htm (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Statistics Canada. 2013. Canada (Code 01) (Table). National Household Survey (NHS) Profile. 2011 National Household Survey. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 99-004-XWE. Ottawa. Available online: http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E (accessed on 21 July 2022).

- Cecco, L. Burned Churches Stir Deep Indigenous Ambivalence over Faith of Forefathers. The Guardian. 2021. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/jul/04/canada-burned-churches-indigenous-catholicism (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Chan, W.Y.A. Teaching Religious Literacy to Combat Religious Bullying: Insights from North American Secondary Schools; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2021; ISBN 9780367640415. [Google Scholar]

- Survey and Analysis Report: The Experience of Sikh Students in Peel. 2016 Update. Available online: https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/worldsikh/pages/594/attachments/original/1493222417/WSO_Bullying_Survey_and_Analysis_Report.pdf?1493222417 (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Special Issue of Religion & Education on Religious Literacy in the Professions. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/toc/urel20/48/1 (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Prothero, S. Religious Literacy: What Every American Needs to Know—and Doesn’t; Barnes and Noble: New York, NY, USA, 2007; ISBN 9780060859527. [Google Scholar]

- The American Academy of Religion Guidelines for Teaching about Religion in K-12 Public Schools in the United States. Available online: https://www.aarweb.org/common/Uploaded%20files/Publications%20and%20News/Guides%20and%20Best%20Practices/AARK-12CurriculumGuidelinesPDF.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- National Council for the Social Studies College, Career & Civic Life: C3 Framework for Social Studies State Standards. Available online: https://www.socialstudies.org/system/files/2022/c3-framework-for-social-studies-rev0617.2.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- The American Academy of Religion Religious Literacy Guidelines: What U.S. College Graduates Need to Understand about Religion. Available online: https://www.aarweb.org/AARMBR/Publications-and-News-/Guides-and-Best-Practices-/Teaching-and-Learning-/AAR-Religious-Literacy-Guidelines.aspx?WebsiteKey=61d76dfc-e7fe-4820-a0ca-1f792d24c06e (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Davie, G. Foreword. In Religious Literacy in Policy and Practice; Dinham, A., Francis, M., Eds.; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2015; pp. vii–xi. ISBN 9781447316657. [Google Scholar]

- Religious Literacy Leadership in Higher Education: An Analysis of Challenges of Religious Faith, and Resources for Meeting Them, for University Leaders. Religious Literacy in Higher Education Programme. Available online: https://research.gold.ac.uk/id/eprint/3916/1/RLLP_Analysis_AW_email.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Crisp, B.R.; Dinham, A. Are the profession’s education standards promoting the religious literacy required for twenty-first century social work practice? Br. J. Soc. Work. 2019, 49, 1544–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinham, A. Religious literacy and public and professional settings. In Routledge International Handbook of Religion, Spirituality and Social Work; Crisp, B., Ed.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2017; pp. 257–264. Available online: https://research.gold.ac.uk/id/eprint/19624/ (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Dinham, A.; Jones, S.H. Religion, public policy, and the academy: Brokering public faith in a context of ambivalence? J. Contemp. Relig. 2012, 27, 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesta, G.; Aldridge, D.; Hannam, P.; Whittle, S. Religious Literacy: A Way Forward for Religious Education? A Report Submitted to the Culham St Gabriel’s Trust. 2019. Available online: https://www.reonline.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Religious-Literacy-Biesta-Aldridge-Hannam-Whittle-June-2019.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Jones, S.H. Religious literacy in higher education. In Religious Literacy in Policy and Practice; Dinham, A., Francis, M., Eds.; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2015; pp. 187–206. ISBN 9781447316657. [Google Scholar]

- Soules, K.E.; Jafralie, S. Religious Literacy in Teacher Education. Relig. Educ. 2021, 38, 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S. Religious literacy: Spaces of teaching and learning about religion and belief. J. Beliefs Values 2020, 41, 129–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Street, B. What’s ‘new’ in New Literacy Studies? Critical approaches to literacy in theory and practice. Curr. Issues Comp. Educ. 2003, 5, 76–91. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, W.Y.A.; Mistry, H.; Reid, E.; Zaver, A.; Jafralie, S. Recognition of context and experience: A civic-based Canadian conception of religious literacy. J. Beliefs Values 2019, 41, 255–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, R. Religious Education: An Interpretive Approach; Hodder & Stoughton: London, UK, 1997; ISBN 978-0340688700. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, R. Signposts—Policy and Practice for Teaching about Religions and Nonreligious Worldviews in Intercultural Education; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nesbitt, E. Gender and Religious Tradition: The Role-Learning of British Hindu Children. Gend. Educ. 1993, 5, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinham, A.; Francis, M. (Eds.) Religious Literacy in Policy and Practice; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2015; ISBN 9781447316657. [Google Scholar]

- Crisp, B.R. Social Work and Spirituality in a Secular Society. J. Soc. Work. 2008, 8, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisp, B.R. (Ed.) The Routledge Handbook of Religion, Spirituality and Social Work; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2017; ISBN 9780367352196. [Google Scholar]

- Allport, G.W. The Nature of Prejudice; Addison-Wesley Publishing Company: Reading, UK, 1951; ISBN 9780201001785. [Google Scholar]

- Allport, G.W. The Individual and His Religion; The MacMillan Company: New York, NY, USA, 1954; ISBN 978-0020831303. [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew, T.F.; Tropp, L.R. When Groups Meet: The Dynamics of Intergroup Contact; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2011; ISBN 9780203826461. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, S.; van Laar, C.; Sidanius, J. The effects of ingroup and outgroup friendships on ethnic attitudes in college: A longitudinal study. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2003, 6, 76–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidanius, J.; Levin, S.; Van Laar, C.; Sears, D.O. The Diversity Challenge: Social Identity and Intergroup Relations on the College Campus; Russell Sage Foundation. 2008. Available online: https://policycommons.net/artifacts/1356656/the-diversity-challenge-social-identity-and-intergroup-relations-on-the-college-campus/1969100/ (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Van Laar, C.; Levin, S.; Sinclair, S.; Sidanius, J. The effect of university roommate contact on ethnic attitudes and behavior. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 41, 329–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, J.; Brown, R.; Zagefka, H.; Funke, F.; Kessler, T.; Mummendey, A.; Maquil, A.; Demoulin, S.; Leyens, J.-P. Does contact reduce prejudice or does prejudice reduce contact? A longitudinal test of the contact hypothesis among majority and minority groups in three European countries. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 96, 843–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minard, R.D. Race relationships in the Pocohontas coal field. J. Soc. Issues 1952, 8, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, J.M. Religious education as body worlds to religious worlds. In Religious Education as Encounter: A Tribute to John M. Hull; Miedema, S., Ed.; Waxman: Münster/Berlin, Germany, 2009; Issue 14; Series Religious Diversity and Education in Europe; pp. 21–34. ISBN 978-3-8309-1894-3. [Google Scholar]

- Allport, G.W. The religious context of prejudice. J. Sci. Study Relig. 1966, 5, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maclean’s 2022 University Guide. Available online: https://www.macleans.ca/hub/education-rankings/ (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- EduRank’s 22 Best Universities for Social Work in Canada in 2022. Available online: https://edurank.org/psychology/social-work/ca/ (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Government of British Columbia School Act, RSBC 1996, c 412. Available online: https://canlii.ca/t/5556x (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- BC Teachers’ Council. Available online: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/governments/organizational-structure/ministries-organizations/boards-commissions-tribunals/bctc (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Simon Fraser University Preservice Professional Studies (PPS), Student Handbook 2021–2022. Faculty of Education. Available online: https://www.sfu.ca/content/sfu/education/teachersed/current-students/downloads-forms-links/_jcr_content/main_content/download_0/file.res/PPS%20Student%20Handbook%202021-22.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Simon Fraser University Social Justice in Education Minor Calendar 2022. Available online: https://www.sfu.ca/students/calendar/2022/fall/programs/social-justice-in-education/minor.html (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Simon Fraser University Professional Development Program—Program Goals. Available online: https://www.sfu.ca/education/teachersed/programs/pdp/goals/10-goals.html (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Religiosity in Canada and Its Evolution from 1985–2019. Catalogue no. 75-006-x. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/75-006-x/2021001/article/00010-eng.htm (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- The Religious, Spiritual, Secular and Social Landscapes of the Pacific Northwest-Part 1. Available online: https://uwspace.uwaterloo.ca/bitstream/handle/10012/12218/Cascadia%20report%20final%20combined%2008-2017.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Focus on Geography Series, 2016 Census. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 98-404-X2016001. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/as-sa/fogs-spg/Facts-PR-Eng.cfm?TOPIC=7&LANG=Eng&GK=PR&GC=59 (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Government of British Columbia Multiculturalism and Anti-Racism. Available online: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/governments/multiculturalism-anti-racism (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Government of British Columbia Health Professions Act, RSBC 1996, c 183. Available online: https://canlii.ca/t/534hx (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- British Columbia College of Nurses & Midwives Entry-Level Competencies for Registered Nurses. Available online: https://www.bccnm.ca/Documents/competencies_requisite_skills/RN_entry_level_competencies_375.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Government of British Columbia Social Workers Act, SBC 2008, c 31. Available online: https://canlii.ca/t/524z7 (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- BC College of Social Workers Code of Ethics and Standards of Practice. Available online: https://bccsw.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/BCCSW-CodeOfEthicsStandardsApprvd.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Part 1 of the Constitution Act, 1982, Being Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982 (UK), c 11. Available online: https://www.canlii.org/en/ca/laws/stat/schedule-b-to-the-canada-act-1982-uk-1982-c-11/latest/schedule-b-to-the-canada-act-1982-uk-1982-c-11.html (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- BC College of Social Workers Strategic Planning 2021–2023 Strategic Priorities. Available online: https://bccsw.ca/wp-content/uploads/BCCSW-Strategic-Directions-2021-2023.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- University of Victoria Bachelor of Social Work Field Education Manual 2020. Available online: https://www.uvic.ca/hsd/socialwork/assets/docs/Practicum/fieldmanual.bsw2020.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Alberta Education Teaching Quality Standard. Available online: https://open.alberta.ca/dataset/14d92858-fec0-449b-a9ad-52c05000b4de/resource/afc2aa25-ea83-4d23-a105-d1d45af9ffad/download/edc-teaching-quality-standard-english-2020.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Government of Alberta Social studies: Highlights of the Draft Social Studies Design Blueprint. Available online: https://www.alberta.ca/curriculum-social-studies.aspx (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Safe and Caring Schools for Students of all Faiths: A Guide for Teachers. Available online: https://acgc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/PK1-AllFaiths.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- 2021–2022 STUDENT HANDBOOK: Information for Students in the Teacher Education Program. University of Lethbridge. Available online: https://www.ulethbridge.ca/sites/default/files/2022/02/2022_educ_student_hdbk_feb.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- University of Lethbridge Religious Studies Education. Available online: https://www.ulethbridge.ca/sites/ross/files/imported/academic-calendar/2022-23/Undergraduate-Calendar.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Government of Alberta Health Professions Act, RSA 2000, c H-7. Available online: https://canlii.ca/t/557cw (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- College of Registered Nurses of Alberta Requisite Skills and Abilities for Becoming a Registered Nurse in Alberta. Available online: https://www.athabascau.ca/health-disciplines/_documents/requisite-skills-and-abilities-for-becoming-a-registered-nurse-in-alberta-2021.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Shaping Tomorrow’s Nursing Leaders: Faculty of Nursing Strategic Plan 2018–2023. Available online: https://www.ualberta.ca/nursing/media-library/about/uafn-strategic-plan-2018-2023-final-sept.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- University of Alberta. 2020 Strategic Plan for Equity, Diversity, and Inclusivity. Faculty of Nursing. Available online: https://www.ualberta.ca/nursing/media-library/fon-2020-edi-strategic-plan.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Bachelor of Science in Nursing—Collaborative. Available online: https://calendar.ualberta.ca/preview_program.php?catoid=36&poid=42893&returnto=11339 (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Alberta College of Social Workers Standards of Practice. Available online: https://acsw.in1touch.org/uploaded/web/website/DRAFT%20ACSW%20Standards%20of%20Practice%20Bill%2021%20Implementation%2002282019.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- University of Calgary Field Education Manual: Bachelor of Social Work, Master of Social Work. Available online: https://socialwork.ucalgary.ca/sites/default/files/Field_Education/Field_Education_Manual.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Faculty of Social Work Equity, Diversity, Inclusion, Decolonization, and Anti-Oppression Statement. Available online: https://socialwork.ucalgary.ca/about/about-faculty/equity-diversity-and-inclusion. (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- University of Calgary Calendar 2022-2023: COURSES OF INSTRUCTION, Course Descriptions, Social Work SOWK. Available online: https://www.ucalgary.ca/pubs/calendar/current/social-work.html#8341 (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- University of Calgary Field Education Policy Manual 2020. Bachelor of Social Work, Master of Social Work. Available online: https://socialwork.ucalgary.ca/sites/default/files/student%20-ucalgary-field-education-manual-feb-2020_0.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- “Practice and Evaluation with Organizations” Course Syllabus. Available online: https://socialwork.ucalgary.ca/sites/default/files/Course_Outlines/Winter_2022/SOWK_399_S01_Fotheringham_W2022_EDI_revision.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Ontario Human Rights Commission Section 11: Indigenous Spiritual Practices. Policy on Preventing Discrimination based on Creed. Available online: https://www.ohrc.on.ca/en/policy-preventing-discrimination-based-creed/11-indigenous-spiritual-practices (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Ontario Ministry of Education. Equity and Inclusive Education in Ontario Schools: Guidelines for Policy Development and Implementation. Available online: https://www2.yrdsb.ca/sites/default/files/migrate/files/inclusiveguide.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Ontario Ministry of Education Stepping Stones: A Resource of Educators Working with Youth Aged 12 to 25. Available online: http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/document/brochure/SteppingStonesPamphlet.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Ontario College of Teachers Professional Standards. Available online: https://www.oct.ca/public/professional-standards (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Ontario College of Teachers Professional Learning Framework for the Teaching Profession. Available online: https://www.oct.ca/-/media/PDF/Professional%20Learning%20Framework/framework_e.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario Embracing Cultural Diversity in Health Care: Developing Cultural Competence. Available online: https://rnao.ca/sites/rnao-ca/files/Embracing_Cultural_Diversity_in_Health_Care_-_Developing_Cultural_Competence.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Chan, W.Y.A.; Sitek, J. Religious Literacy in Healthcare. Relig. Educ. 2021, 48, 102–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario New eLearning Resource: Engaging Indigenous People Who Use Substances. Available online: https://rnao.ca/news/new-elearning-resource-engaging-indigenous-people-who-use-substances (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- McMaster University. About the School of Social Work. Available online: https://socialwork.mcmaster.ca/about (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Ontario College of Social Workers and Social Service Workers Code of Ethics and Standards of Practice Handbook. Second Edition. Available online: https://www.ocswssw.org/wp-content/uploads/Code-of-Ethics-and-Standards-of-Practice-September-7-2018.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- McMaster University Faculty of Social Work, Social Sciences: Explore Your Interests in First Year. Available online: https://socialsciences.mcmaster.ca/future/social-sciences-1. (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- McMaster University Faculty of Social Work Program Home Page. Available online: https://socialwork.mcmaster.ca/programs#honours-bachelor-of-social-work (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- McMaster University Faculty of Social Work “Indigenizing Social Work Practice Approaches”. Available online: https://socialwork.mcmaster.ca/courses/indigenizing-social-work-practice-approaches. (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- McMaster University Faculty of Social Work “Social Work and Indigenous Peoples”. Available online: https://socialwork.mcmaster.ca/courses/social-work-and-indigenous-peoples. (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Immigration and Ethnocultural Diversity: Key Results from the 2016 Census. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/171025/dq171025b-eng.htm?indid=14428-4&indgeo=0 (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Centre for Race and Culture Anti-Racism Education in Canada: Best Practices. Available online: https://cfrac.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Anti-Racism-Education-in-Canada-1.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Ontario College of Teachers Professional Advisory on Anti-Black Racism. Available online: https://www.oct.ca/-/media/PDF/professional_advisory_ABR/Professional_Advisory_ABR_EN.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Patrick, M. Stories Alberta social studies teachers tell: Influences of Christianity, liberalism, and secularism. Alta. J. Educ. Res. 2022, 68, 191–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christians Remain World’s Largest Religious Group, but They Are Declining in Europe. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/04/05/christians-remain-worlds-largest-religious-group-but-they-are-declining-in-europe/ (accessed on 26 July 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Patrick, M.; Chan, W.Y.A. Can I Keep My Religious Identity and Be a Professional? Evaluating the Presence of Religious Literacy in Education, Nursing, and Social Work Professional Programs across Canada. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 543. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12080543

Patrick M, Chan WYA. Can I Keep My Religious Identity and Be a Professional? Evaluating the Presence of Religious Literacy in Education, Nursing, and Social Work Professional Programs across Canada. Education Sciences. 2022; 12(8):543. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12080543

Chicago/Turabian StylePatrick, Margaretta, and W. Y. Alice Chan. 2022. "Can I Keep My Religious Identity and Be a Professional? Evaluating the Presence of Religious Literacy in Education, Nursing, and Social Work Professional Programs across Canada" Education Sciences 12, no. 8: 543. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12080543

APA StylePatrick, M., & Chan, W. Y. A. (2022). Can I Keep My Religious Identity and Be a Professional? Evaluating the Presence of Religious Literacy in Education, Nursing, and Social Work Professional Programs across Canada. Education Sciences, 12(8), 543. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12080543