Who Sends Scores to GRE-Optional Graduate Programs? A Case Study Investigating the Association between Latent Profiles of Applicants’ Undergraduate Institutional Characteristics and Propensity to Submit GRE Scores

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Graduate Record Examination

1.2. GRE-Optional Policies

1.2.1. Background and Prior Research

1.2.2. Predicting GRE Score Submission

1.3. Current Investigation

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Admissions Data

2.2.2. Undergraduate Institutional Characteristics

2.3. Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Sample Description

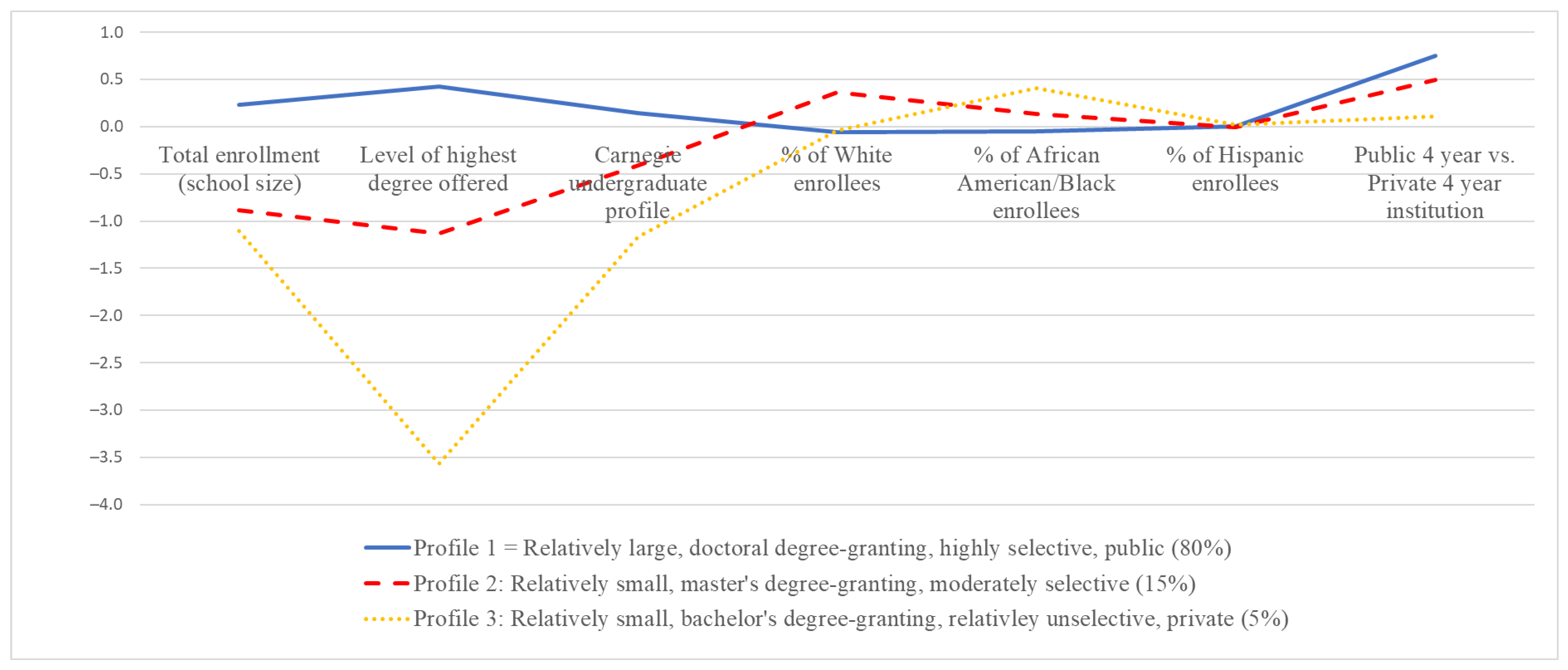

3.2. Latent Profile Analyses

3.3. Predicting GRE Score Submission

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| M (SD) | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Public (vs. Private) | -- | 68.46 |

| Carnegie Undergraduate Profile | 12.98 (2.05) | |

| 1. two-year, higher part-time | 0.53 | |

| 2. two-year, mixed part/full-time | 0.15 | |

| 3. two-year, medium full-time | 0.30 | |

| 4. two-year, higher full-time | 0.00 | |

| 5. four-year, higher part-time | 1.36 | |

| 6. four-year, medium full-time, inclusive, lower transfer-in | 0.13 | |

| 7. four-year, medium full-time, inclusive, higher transfer-in | 0.85 | |

| 8. four-year, medium full-time, selective, lower transfer-in | 0.03 | |

| 9. four-year, medium full-time, selective, higher transfer-in | 2.56 | |

| 10. four-year, full-time, inclusive, lower transfer-in | 1.98 | |

| 11. four-year, full-time, inclusive, higher transfer-in | 5.87 | |

| 12. four-year, full-time, selective, lower transfer-in | 10.82 | |

| 13. four-year, full-time, selective, higher transfer-in | 18.14 | |

| 14. four year, full-time, more selective, lower transfer-in | 49.99 | |

| 15. four year, full-time, more selective, higher transfer-in | 7.30 | |

| Highest Degree Offered | 5.55 (1.05) | -- |

| 1. associate’s degree | 0.98 | |

| 2. bachelor’s degree | 3.98 | |

| 3. postbaccalaureate certificate | 0.00 | |

| 4. master’s degree | 9.27 | |

| 5. post-master’s certificate | 5.38 | |

| 6. doctoral degree | 80.39 | |

| Total Enrollment | 12,171.93 (8936.63) | -- |

| % of White Enrollees | 58.57 (13.76) | -- |

| % of African-American/Black Enrollees | 8.35 (8.25) | -- |

| % of Hispanic/Latino Enrollees | 11.96 (7.52) | -- |

References

- Gewin, V. US geoscience programmes drop controversial admissions test. Nature 2020, 584, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langin, K. Ph.D. programs drop standardized exam. Science 2019, 364, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, S.E.; LeBreton, J.; Keith, M.; Tay, L. Bias, fairness, and validity in graduate-school admissions: A psychometric perspective. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.W.; Stassun, K. A test that fails. Nature 2014, 510, 303–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.D.; O’Connell, A.B.; Cook, J.G. Predictors of student productivity in biomedical graduate school applications. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, S.L.; Erenrich, E.S.; Levine, D.L.; Vigoreaux, J.; Gile, K. Multi-institutional study of GRE scores as predictors of STEM PhD degree completion: GRE gets a low mark. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0206570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuters. True Claim: Some Graduate Schools Are Waiving GRE Test Requirements Because of COVID-19. 2020. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-factcheck-coronavirus-gre-waive/true-claim-some-graduate-schools-are-waiving-gre-test-requirements-because-of-covid-19-idUSKCN21Q2Z6 (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Cahn, P.S. Do health professions graduate programs increase diversity by not requiring the graduate record examination for admission? J. Allied Health 2015, 44, 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Millar, J.A. The GRE in public health admissions: Barriers, waivers, and moving forward. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 796–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpentier, V. Expansion and Differentiation in Higher Education: The Historical Trajectories of the UK, the USA and France (Working Paper 33). Centre for Global Higher Education. 2018. Available online: https://www.researchcghe.org/publications/working-paper/expansion-and-differentiation-in-higher-education-the-historical-trajectories-of-the-uk-the-usa-and-france/ (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- U.S. Department of Education. Fast facts: Educational institutions. National Center for Education Statistics. 2021. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=84 (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Vaughn, K.W. The Graduate Record Examinations. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1947, 7, 745–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. The Graduate Record Examination; Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching: Stanford, CA, USA, 1941. [Google Scholar]

- Savage, H.J. Fruit of an impulse: Forty-five years of the Carnegie Foundation (1905–1950); Harcourt, Brace and Company: San Diego, CA, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Conrad, L.; Trisman, D.; Miller, R. (Eds.) GRE Graduate Record Examinations Technical Manual; Educational Testing Service: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Briel, J.B.; O’Neill, K.A.; Scheuneman, J.D. (Eds.) GRE Technical Manual: Test Development, Score Interpretation, and Research for the Graduate Record Examinations Program; Educational Testing Service: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lemann, N. The Big Test: The Secret History of the American Meritocracy; Farrar, Straus and Giroux: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Educational Testing Service. GRE. Graduate Record Examinations. Guide to the Use of Scores. 2021–2022; ETS: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Barshay, J. Proof points: Test-Optional Policies Didn’t Do Much to Diversify College Student Populations. The Hechinger Report. 2021. Available online: https://hechingerreport.org/proof-points-test-optional-policies-didnt-do-much-to-diversify-college-student-populations/ (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Lucido, J.A. Understanding the test-optional movement. In Measuring Success: Testing, Grades, and the Future of College Admissions; Buckley, J., Letukas, L., Wildavsky, B., Eds.; John Hopkins University Press: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 145–170. [Google Scholar]

- Zwick, R. College Admission Testing; National Association for College Admission Counseling: Arlington, VA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jaschik, S. SAT Skepticism in New Form. Inside Higher Ed. 2009. Available online: https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2009/04/21/sat-skepticism-new-form (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- McDermott, A. Surviving without the SAT. Chronicle of Higher Education. 2008. Available online: https://www.chronicle.com/article/surviving-without-the-sat-18874/?cid2=gen_login_refresh&cid=gen_sign_inN (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- O’Shaughnessy, L. The Other Side of ‘Test Optional’. The New York Times. 2009. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2009/07/26/education/edlife/26guidance-t.html (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Marston, A.R. It is time to reconsider the Graduate Record Examination. Am. Psychol. 1971, 26, 653–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, M.; McNeil, J.S.; King, S.W. The GRE: A question of validity in predicting performance in professional schools of social work. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1984, 44, 945–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, R.J.; Williams, W.M. Does the Graduate Record Examination predict meaningful success in the graduate training of psychology? A case study. Am. Psychol. 1997, 52, 630–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posselt, J.R. Inside Graduate Admissions: Merit, Diversity, and Faculty Gatekeeping; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, M.C.; Ostreko, A. GREs, public posting, and holistic admissions for diversity in professional psychology: Commentary on Callahan et al. Train. Educ. Prof. Psychol. 2018, 12, 286–290. [Google Scholar]

- Clayton, V. The Problem with the GRE. The Atlantic. 2016. Available online: https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2016/03/the-problem-with-the-gre/471633/ (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Dang, K.V.; Rerolle, F.; Ackley, S.F.; Irish, A.M.; Mehta, K.M.; Bailey, I.; Fair, E.; Miller, C.; Bibbins-Domingo, K.; Wong-Moy, E.; et al. A randomized study to assess the effect of including the Graduate Record Examinations results on reviewer scores for underrepresented minorities. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2021, 190, 1744–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.W.; Zwickl, B.M.; Posselt, J.R.; Silvestrini, R.T.; Hodapp, T. Typical physics Ph. D. admissions criteria limit access to underrepresented groups but fail to predict doctoral completion. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaat7550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moneta-Koehler, L.; Brown, A.M.; Petrie, K.A.; Evans, B.J.; Chalkley, R. The limitations of the GRE in predicting success in biomedical graduate school. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0166742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Small, A. Range Restriction, Admissions Criteria, and Correlation Studies of Standardized Tests. 2017. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1709.02895 (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Weissman, M.B. Do GRE scores help predict getting a physics Ph. D.? A comment on a paper by Miller et al. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaax378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeates, T.O. A Critical Analysis of Recent Studies of the GRE and Other Metrics of Graduate Student Preparation. 2018. Available online: https://docplayer.net/208238816-A-critical-analysis-of-recent-studies-of-the-gre-and-other-metrics-of-graduate-student-preparation.html (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Grove, W.A.; Wu, S. The search for economics talent: Doctoral completion and research productivity. Am. Econ. Rev. 2007, 97, 506–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ma, T.; Wood, K.E.; Xu, D.; Guidotti, P.; Pantano, A.; Komarova, N.L. Admission Predictors for Success in a Mathematics Graduate Program. 2018. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1803.00595.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Mendoza-Sanchez, I.; de Gruyter, J.N.; Savage, N.T.; Polymenis, M. Undergraduate GPA predicts biochemistry PhD completion and is associated with time to degree. CBE—Life Sci. Educ. 2022, 21, ar19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, B.O.; Lubinski, D.; Benbow, C.P. Psychological constellations assessed at age 13 predict distinct forms of eminence 35 years later. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 30, 444–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, A.B.; Wu, S. Forecasting job placements of economics graduate students. J. Econ. Educ. 2000, 31, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Educational Testing Service. A Snapshot of the Individuals Who Took the GRE General Test: July 2016–June 2021; ETS: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Schwager, I.T.; Hülsheger, U.R.; Bridgeman, B.; Lang, J.W. Graduate student selection: Graduate Record Examination, socioeconomic status, and undergraduate grade point average as predictors of study success in a western European university. Int. J. Sel. Assess. 2015, 23, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Educational Research Association; American Psychological Association; National Council on Measurement in Education. Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing; American Educational Research Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, D.A.; Tang, C.; Song, Q.C.; Wee, S. Dropping the GRE, keeping the GRE, or GRE-optional admissions? Considering tradeoffs and fairness. Int. J. Test. 2022, 22, 43–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, N.W.; Wang, M.M. Predicting long-term success in graduate school: A collaborative validity study. ETS Res. Rep. Ser. 2005, 2005, i-61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Graduate Schools. Ph.D. Completion and Attrition: Analysis of Baseline Demographic Data from the Ph.D. Completion Project; Council of Graduate Schools: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Boone, Young & Associates, Inc.; Educational Testing Service. Minority Enrollment in Graduate and Professional Schools: Recruitment, Admissions, Financial Assistance. A technical Assistance Handbook; U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1984.

- Haverlah, A.K. No GRE, No Problem: Texas’ Graduate Schools See Increase in Enrollment and Diversity. Reporting Texas. 2021. Available online: https://reportingtexas.com/no-gre-no-problem-texas-graduate-schools-see-increase-in-enrollment-and-diversity/ (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Spike, C. Grad School Diversity Increases with Test POLICY, New Programs. Princeton Alumni Weekly. 2021. Available online: https://paw.princeton.edu/article/grad-school-diversity-increases-test-policy-new-programs (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Cooper, C.A.; Knotts, H.G. Do I have to take the GRE? Standardized testing in MPA admissions. PS Political Sci. Politics 2019, 52, 470–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, L.M.; Zwickl, B.M.; Franklin, S.V.; Miller, C.W. Physics GRE Requirements Create Uneven Playing Field for Graduate Applicants. Proceedings in Physics Education Research Conference 2020. 2020. Available online: https://par.nsf.gov/biblio/10310048 (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Lozano, I. I’m a Working-Class Mexican American Student. The SAT Doesn’t Hurt Me—It Helps. The Washington Post. 5 October 2020. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2020/10/05/sat-working-class-student-university-california/ (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Posselt, J.R. Trust networks: A new perspective on pedigree and the ambiguities of admissions. Rev. High. Educ. 2018, 41, 497–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nye, C.D.; Ryan, A.M. Improving graduate-school admissions by expanding rather than eliminating predictors. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padgett, R.D.; Goodman, K.M.; Johnson, M.P.; Saichaie, K.; Umbach, P.D.; Pascarella, E.T. The impact of college student socialization, social class, and race on need for cognition. New Dir. Inst. Res. 2010, 2010, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidman, J.C. Undergraduate Socialization: A Conceptual Approach. In Foundations of American Higher Education, 2nd ed.; Bess, J.L., Webster, D.S., Eds.; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1989; pp. 114–135. [Google Scholar]

- Brown University; Graduate School. Diversity and Inclusion. 2022. Available online: https://www.brown.edu/academics/gradschool/diversity-0 (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- North Carolina State University; College of Engineering. Diversity and Inclusion. 2022. Available online: https://www.engr.ncsu.edu/faculty-staff/efa/diversity-and-inclusion/ (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- The Ohio State University. Campus Conversation on Graduate Education: Diversity and Inclusion. 2022. Available online: https://gradsch.osu.edu/sites/default/files/resources/pdfs/CC_Onesheet_DiversityAndInclusion.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- The State University of New York. What Is Diversity at Suny? 2022. Available online: https://www.suny.edu/diversity/about/ (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- The Trustees of Princeton University. Access, Diversity, and Inclusion. The Graduate School. Princeton University. 2022. Available online: https://graddiversity.princeton.edu/ (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- U.S. Department of Education. 2019 institutional characteristic data. National Center for the Educational Statistics. Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System. 2019. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/use-the-data (accessed on 26 February 2020).

- Council of Graduate Schools. Graduate Enrollment and Degrees: 2009–2019; Council of Graduate Schools: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Weller, B.E.; Bowen, N.K.; Faubert, S.J. Latent class analysis: A guide to best practice. J. Black Psychol. 2020, 46, 287–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User’s Guide (8th ed.). 1998–2017. Available online: https://www.statmodel.com/download/usersguide/MplusUserGuideVer_8.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Lanza, S.T.; Rhoades, B.L. Latent class analysis: An alternative perspective on subgroup analysis in prevention and treatment. Prev. Sci. 2013, 14, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, Y.; Mendell, N.; Rubin, D.B. Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika 2001, 88, 767–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, L.; The Task Force on Statistical Inference. Statistical methods in psychology journals. Am. Psychol. 1999, 54, 594–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Educational Attainment Tables. 2021. Available online: https://www.census.gov/topics/education/educational-attainment/data/tables.html (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- McLachlan, G.; Peel, D. Finite Mixture Models; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Logan, J.A.; Pentimonti, J.M. Introduction to latent class analysis for reading fluency research. In The Fluency Construct; Cummings, K.D., Petscher, Y., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 309–332. [Google Scholar]

- Funder, D.C.; Ozer, D.J. Evaluating Effect Size in Psychological Research: Sense and Nonsense. Adv. Methods Pract. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 2, 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Götz, F.M.; Gosling, S.D.; Rentfrow, P.J. Small effects: The indispensable foundation for a cumulative psychological science. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2022, 17, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Cohen, P.; Chen, S. How big is a big odds ratio? Interpreting the magnitudes of odds ratios in epidemiological studies. Commun. Stat. 2010, 39, 860–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanford, K. Underdetermination of Scientific Theory. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 2017. Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/scientific-underdetermination (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Green, M.J. Latent Class Analysis Was Accurate But Sensitive in Data Simulations. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014, 67, 1157–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevill, S.C.; Carroll, C.D. The Path through Graduate School: A Longitudinal Examination 10 Years after Bachelor’s Degree. Postsecondary Education Descriptive Analysis Report; National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) Report 2007-162; U.S. Department of Education: Washington, DC, USA, 2007.

- U.S. Department of Education Postbaccalaureate Enrollment. Condition of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. 2022. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/chb (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Ekstrom, R. Undergraduate Debt and Participation in Graduate Education: The Relationship between Educational Debt and Graduate School Aspirations, Applications, and Attendance among Students with a Pattern of Full-Time, Continuous Postsecondary Education. ETS Research Report No. 89–45. 1991. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED392374 (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Walpole, M. Emerging from the pipeline: African American students, socioeconomic status, and college experiences and outcomes. Res. High. Educ. 2008, 49, 237–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N | Percentage | % of U.S. BA-Holders | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men | 1191 | 29.83 | 46.73 |

| Women | 2802 | 70.17 | 53.27 |

| African-American/Black | 412 | 10.32 | 9.20 |

| Asian-American | 192 | 4.81 | 9.28 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 392 | 9.81 | 10.02 |

| Other | 142 | 3.55 | -- |

| White | 2855 | 71.51 | 70.09 |

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Ph.D. | 360 | 9.02 |

| Master’s | 3633 | 90.98 |

| Fine Arts | 314 | 7.86 |

| Humanities | 197 | 4.93 |

| Nursing | 453 | 11.34 |

| Social Sciences | 2610 | 65.36 |

| STEM | 419 | 10.49 |

| GRE-Q (n = 411) M (SD) | GRE-V (n = 411) M (SD) | GRE-AW (n = 347) M (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men | 151.78 (7.45) | 155.67 (6.32) | 4.17 (0.72) |

| Women | 149.60 (6.69) | 154.94 (7.13) | 4.27 (0.68) |

| African-American/Black | 145.86 (7.92) | 150.61 (7.69) | 3.54 (0.72) |

| Asian-American | 152.71 (6.25) | 156.48 (6.87) | 4.53 (0.65) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 145.76 (6.98) | 152.58 (6.44) | 3.95 (0.59) |

| Other | 148.24 (7.43) | 153.24 (7.56) | 4.09 (0.67) |

| White | 151.56 (6.59) | 155.93 (6.46) | 4.30 (0.67) |

| Ph.D. Program Applicants | 148.59 (7.11) | 156.06 (6.51) | 4.37 (0.7) |

| Master’s Program Applicants | 151.02 (6.96) | 154.97 (6.91) | 4.19 (0.69) |

| Fine Arts Program Applicants | 148.67 (4.63) | 158.33 (5.28) | 5.00 (0.58) |

| Humanities Program Applicants | 149.72 (8.21) | 158.50 (7.35) | 4.56 (0.64) |

| Nursing Program Applicants | 149.21 (5.32) | 154.83 (5.16) | 4.08 (0.77) |

| Social Sciences Program Applicants | 149.74 (6.98) | 154.42 (6.76) | 4.17 (0.69) |

| STEM Program Applicants | 153.59 (6.13) | 154.64 (6.44) | 4.13 (0.63) |

| Applicants from Profile 1 Schools | 150.70 (7.01) | 154.94 (6.76) | 4.19 (0.70) |

| Applicants from Profile 2 Schools | 147.66 (6.31) | 154.97 (6.85) | 4.33 (0.64) |

| Applicants from Profile 3 Schools | 153.38 (7.43) | 158.32 (6.79) | 4.41 (0.72) |

| Latent Classes | Free Parameters | AIC | BIC | Adjusted BIC | Entropy | LMR p-Value | BLRT p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 21 | 145,469.15 | 145,601.28 | 145,534.56 | 0.995 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 3 | 29 | 139,920.01 | 140,102.49 | 140,010.34 | 0.999 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 4 | 37 | 133,974.23 | 134,207.05 | 134,089.48 | 1.000 | 0.159 | 0.162 |

| 5 | 45 | 54,840.09 | 55,123.24 | 54,980.25 | 0.935 | 0.494 | 0.497 |

| GRE Submitted | GRE Not Submitted | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |

| Relatively large, doctoral degree-granting, highly selective, public | 312 | 9.72 | 2898 | 90.28 |

| Relatively small, master’s degree-granting, moderately selective | 65 | 11.11 | 520 | 88.89 |

| Relatively small, bachelor’s degree-granting, relatively unselective, private | 34 | 17.17 | 164 | 82.83 |

| GRE Score Submitted | ||

|---|---|---|

| Model 1 OR (SE) | Model 2 OR (SE) | |

| Undergraduate Institution Latent Class | ||

| Profile 3 a vs. Profile 1 b | 1.93 (0.38) ** | 2.00 (0.48) ** |

| Profile 2 c vs. Profile 1 | 1.16 (0.17) | 1.23 (0.21) |

| Profile 3 vs. Profile 2 | 1.66 (0.14) * | 1.63 (0.45) |

| Undergraduate GPA | 1.09 (0.17) | |

| Gender (Male = 1) | 1.55 (0.19) *** | |

| Ethnicity/race (Ref. = White) | ||

| Black | 0.72 (0.16) | |

| Hispanic | 1.05 (0.21) | |

| Asian | 1.32 (0.34) | |

| Other | 1.65 (0.47) | |

| Degree applied (Ph.D. = 1) | 2.94 (0.55) *** | |

| Program (Ref. = Social sciences) | ||

| Fine arts | 0.16 (0.07) *** | |

| Humanities | 3.23 (0.71) *** | |

| Nursing | 0.45 (0.11) ** | |

| STEM | 1.92 (0.31) *** | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cho-Baker, S.; Kell, H.J. Who Sends Scores to GRE-Optional Graduate Programs? A Case Study Investigating the Association between Latent Profiles of Applicants’ Undergraduate Institutional Characteristics and Propensity to Submit GRE Scores. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 529. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12080529

Cho-Baker S, Kell HJ. Who Sends Scores to GRE-Optional Graduate Programs? A Case Study Investigating the Association between Latent Profiles of Applicants’ Undergraduate Institutional Characteristics and Propensity to Submit GRE Scores. Education Sciences. 2022; 12(8):529. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12080529

Chicago/Turabian StyleCho-Baker, Sugene, and Harrison J. Kell. 2022. "Who Sends Scores to GRE-Optional Graduate Programs? A Case Study Investigating the Association between Latent Profiles of Applicants’ Undergraduate Institutional Characteristics and Propensity to Submit GRE Scores" Education Sciences 12, no. 8: 529. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12080529

APA StyleCho-Baker, S., & Kell, H. J. (2022). Who Sends Scores to GRE-Optional Graduate Programs? A Case Study Investigating the Association between Latent Profiles of Applicants’ Undergraduate Institutional Characteristics and Propensity to Submit GRE Scores. Education Sciences, 12(8), 529. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12080529