The Ecological Root Metaphor for Higher Education: Searching for Evidence of Conceptual Emergence within University Education Strategies

Abstract

:1. Introduction: Research Motivations

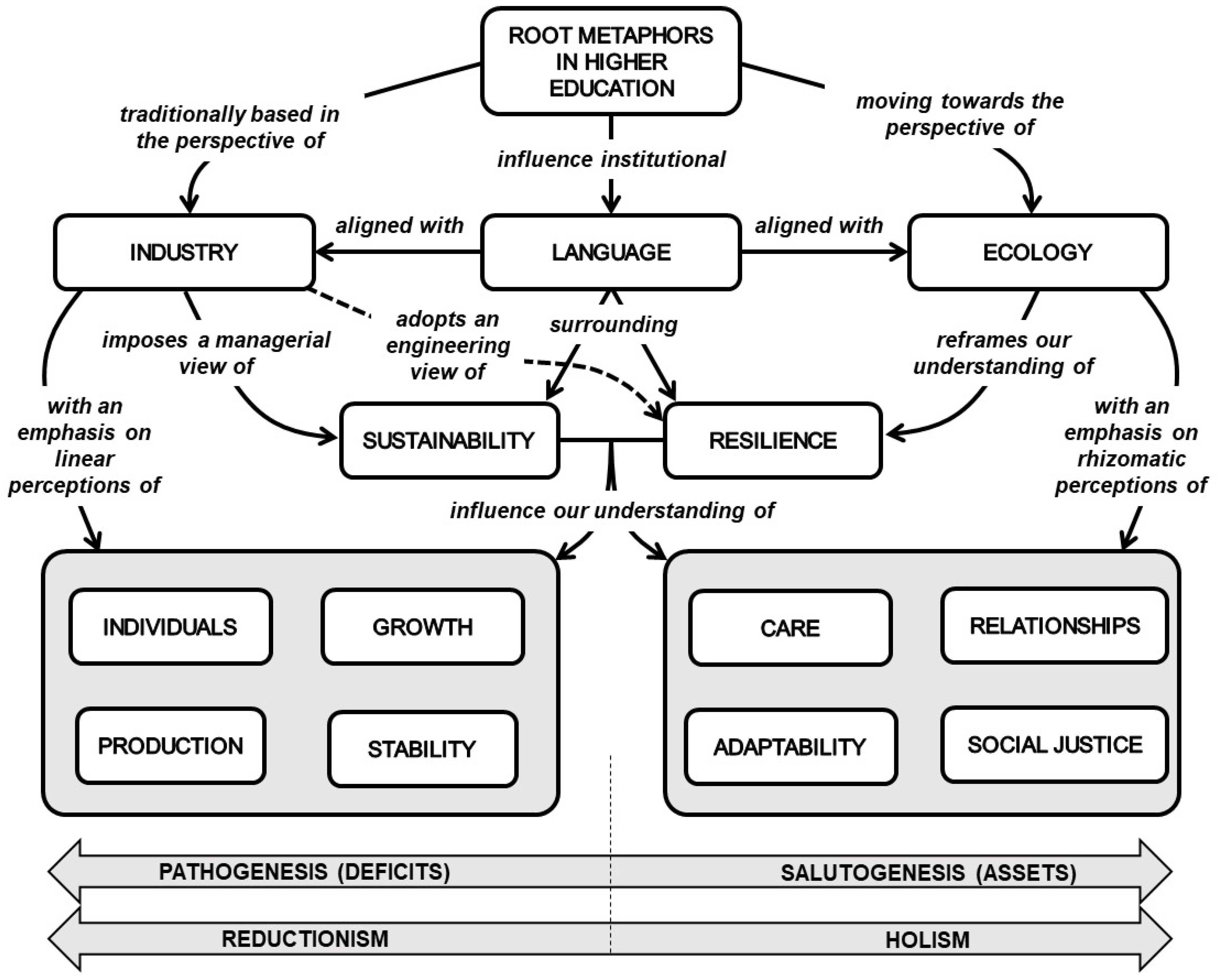

2. The Use of Metaphor in Education

It is no longer a (thinly veiled) secret that in contemporary universities many scholars, both junior and senior, are struggling—struggling to manage their workloads; struggling to keep up with insistent institutional demands to produce more, better and faster; struggling to reconcile professional demands with family responsibilities and personal interests; and struggling to maintain their physical and psychological health and emotional wellbeing.(p. 100)

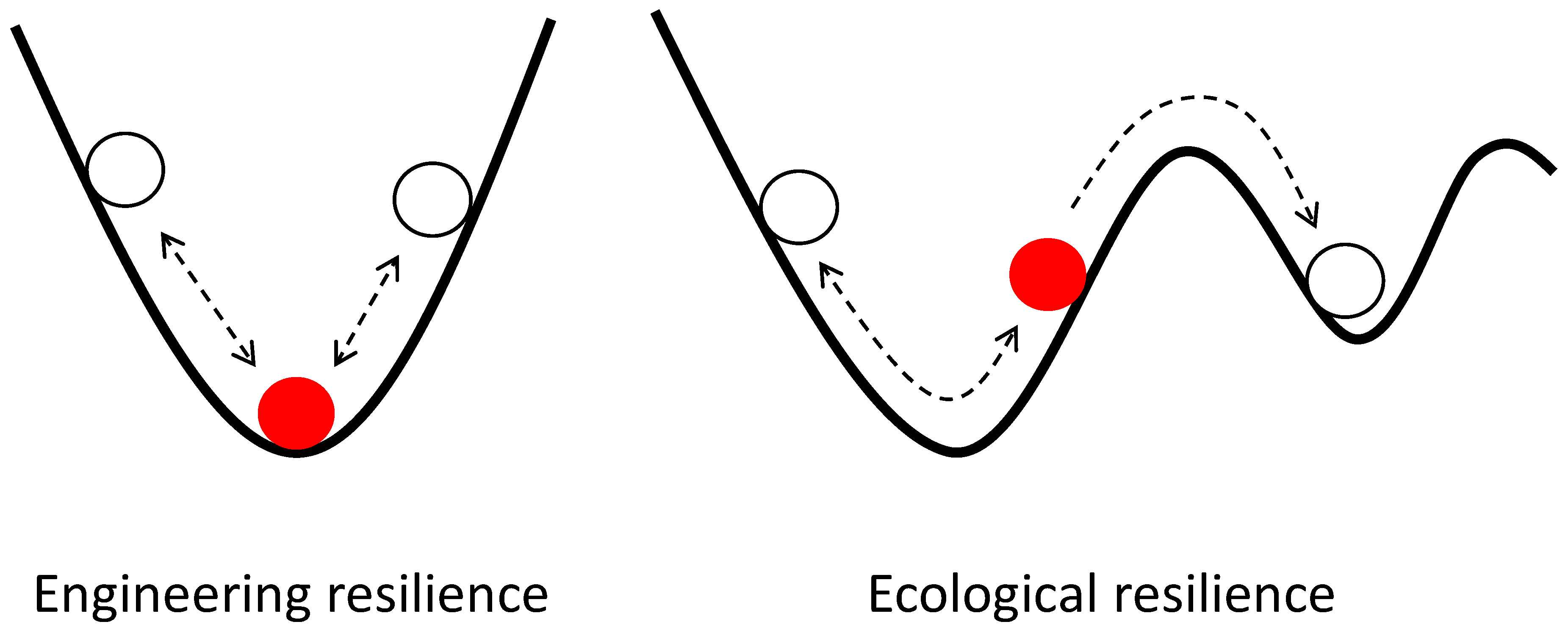

When there are competing root metaphors, such as between ‘ecology’ and the collection of root metaphors underlying the Industrial Revolution, iconic metaphors such as ‘sustainability’ have different meanings that reflect the differences in taken-for-granted root metaphors.[5] (p. 23)

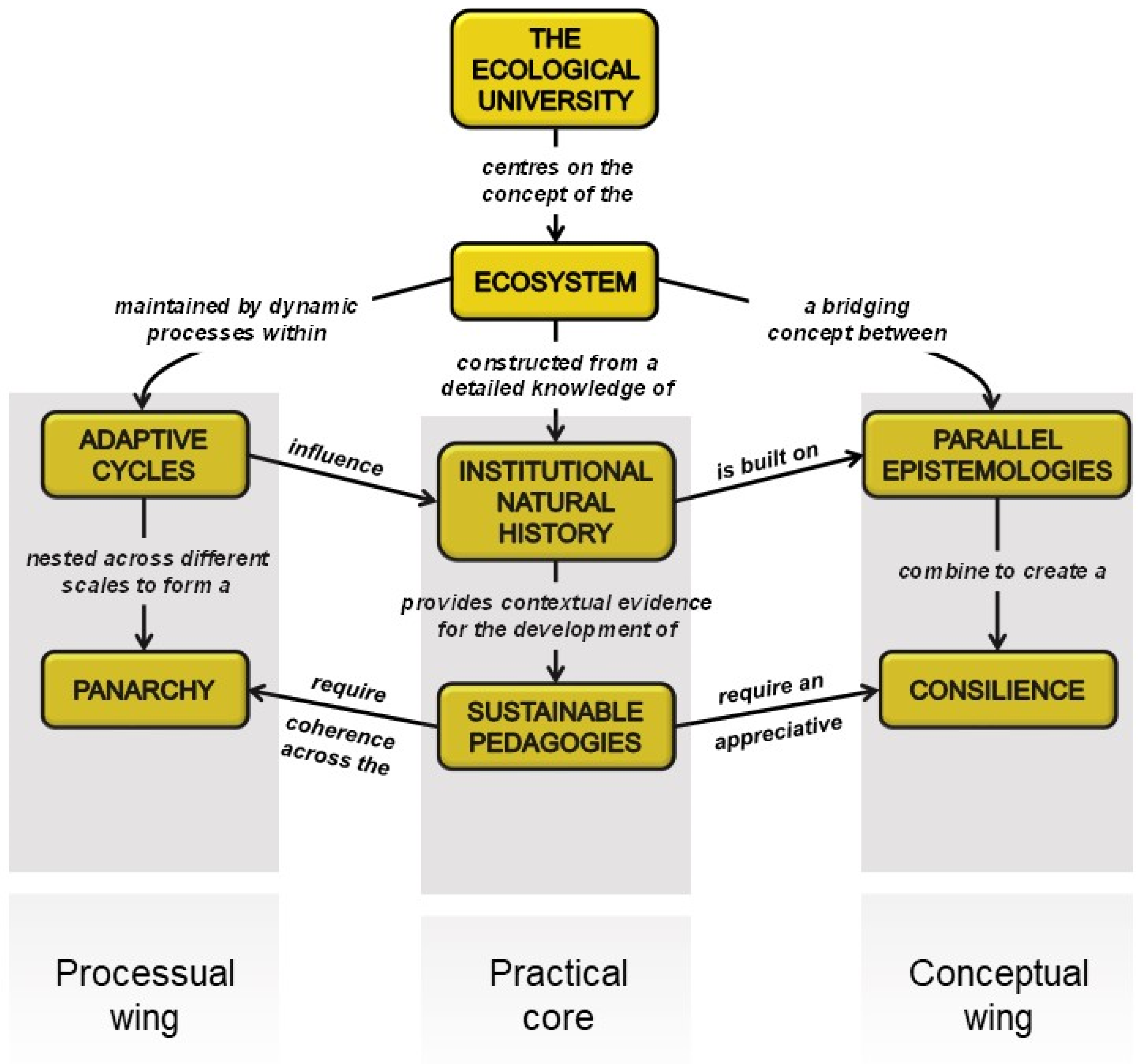

3. The Ecological University Model

Ecological thinking is not simply thinking about ecology or about “the environment”, although these figure as catalysts among its issues. It is a revisioned mode of engagement with knowledge, subjectivity, politics, ethics, science, citizenship, and agency that pervades and reconfigures theory and practice. It does not reduce to a set of rules or methods; it may play out differently from location to location; but it is sufficiently coherent to be interpreted and enacted across widely diverse situations.

In contrast to a biological system, an educational ecosystem needs human actors, and it is dependent upon conscious human behaviour. For an educational ecosystem to be sustainable, its participants must intentionally share joint aims and take action to ensure interconnectedness, interdependence, and open and transparent mutual communication between all partners. In complex and moving systems, many of the components undergo their own change processes, and this information needs to be analysed, updated and shared when working towards common goals.

The use of ecology as a root metaphor foregrounds the relational and interdependent nature of our existence as cultural and biological beings [it] foregrounds relationships, continuities, non-linear patterns of change, and a basic design principle of Nature that favors diversity.(p. 29)

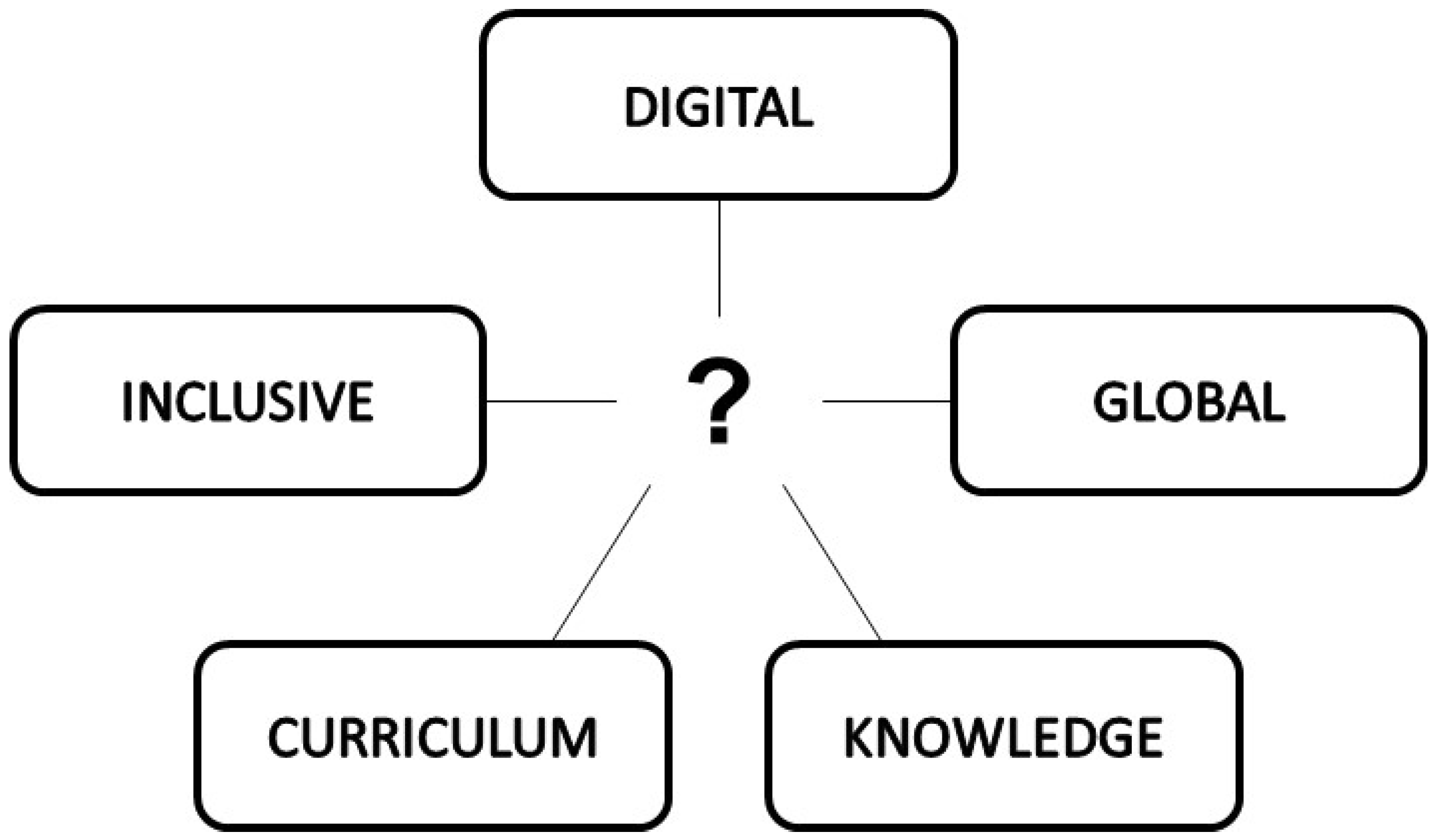

4. Institutional Education Strategies

5. Method

6. Observations

6.1. Teaching and Pedagogy

6.2. Knowledge

what is generally understood as knowledge in the universities of our world represents a very small proportion of the global treasury of knowledge. University knowledge systems in nearly every part of the world are derivations of the Western canon, the knowledge system created some 500 to 550 years ago in Europe by white male scientists. The contemporary university is often characterized as working with colonized knowledge, hence the increasing calls for the decolonization of our universities. The epistemologies of most peoples of the world, whether Indigenous, or excluded on the basis of race, gender or sexuality are missing. However, evidence of other epistemologies and other ways of representing knowledge exist. Without a much deeper analysis of whose knowledge, how that knowledge was gathered and how transformative change is encouraged through deeper attention to knowledge democracy, public engagement in knowledge sharing simply reinforces the existing colonized relations of knowledge power.[41] (p. 7)

By drawing on the wisdom of ecological principles and indigenous worldviews, sustainability teaching and learning can be designed in a way that is focused on learners’ whole selves, empowering learners to become citizens who know how to understand and address problems systemically and intellectually; know how to critically question dominant norms and to listen to a variety of less heard perspectives, engaging their emotions in this process; know how to work with others collaboratively, relationally, and physically in an active process of problem solving; and who know themselves and their places spiritually, who understand their interconnectedness with all life, and who can engage with the living world in a balanced and sustainable way.[43] (p. 272)

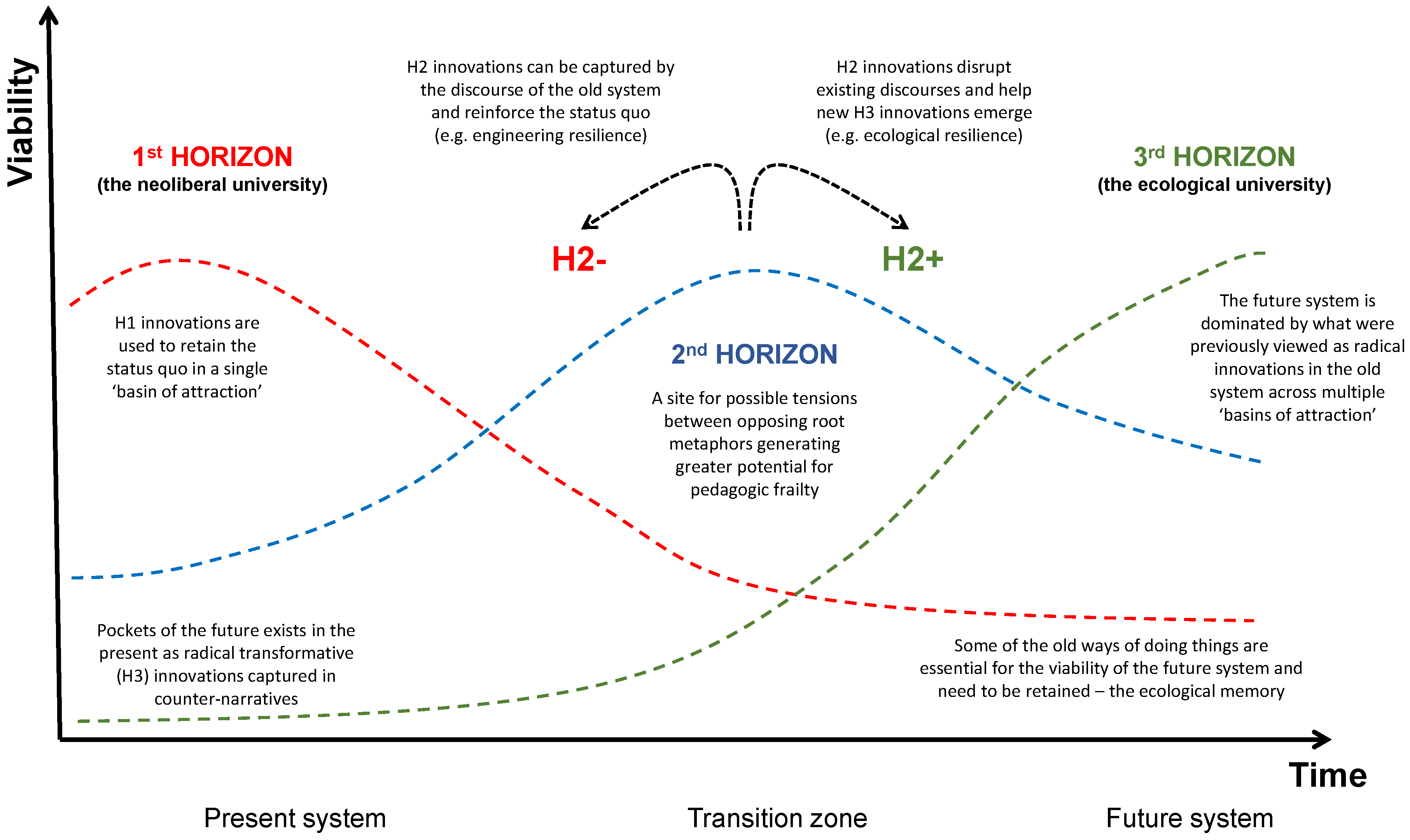

6.3. Technology

furthering adaptability increases the possibility of lock-ins, namely, of cases in which better alternatives exist, but the system is trapped in a basin of attraction. This is due to the fact that adaptability enlarges and deepen the basins. For instance, it has been argued that the lecture has prevailed as the main form of educational delivery due to its capacity to adapt to technological developments while maintaining its overall structure. Thus, teachers have introduced new technological tools—PowerPoint slides, video clips, digital surveys—that were integrated into the lecture, rather than replacing it. While it could be the case that better alternatives exist, the lecture′s adaptability allowed it to prevail. In this case, the introduction of new technologies served to enlarge the basins of attraction, that now encompassed new tools, but the attractors were kept stable. This seems to remain valid even in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and the transition to remote learning.

6.4. Global Excellence

The notion of the “global university” refers to the fact that more and more universities in more and more countries all seem to be playing the same game and therefore increasingly are trying to become the same and to a large extent already have become the same.[61] (p. 37)

7. Conclusions

Truth is always relative to a conceptual system that is defined in large part by metaphor. Most of our metaphors have evolved in our culture over a long period, but many are imposed upon us by people in power. In a culture where the myth of objectivism is very much alive and truth is always absolute truth, the people who get to impose their metaphors on the culture get to define what we consider to be true.[75] (pp. 159–160)

8. Going Forward

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Bessant, J. Dawkins’ Higher Education Reforms and How Metaphors Work in Policy Making. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2002, 24, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botha, E. Why metaphor matters in education. S. Afr. J. Educ. 2009, 29, 431–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourish, D.; Hargie, O. Metaphors of failure and the failures of metaphor: A critical study of root metaphors used by Bankers in Explaining the Banking Crisis. Organ. Stud. 2012, 33, 1045–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giroux, H.A. Neoliberalism’s War on Higher Education; Haymarket Books: Chicago, IL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bowers, C.A. Towards an eco-justice pedagogy. Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, C.; Fidler, B. A new theory of educational change–punctuated equilibrium: The case of the internationalisation of higher education. Br. J. Educ. Stud. 2005, 53, 447–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, C.; Boin, A.; Farjoun, M. Dynamic conservatism: How institutions change to remain the same. In Institutions and Ideals: Philip Selznick’s Legacy for Organizational Studies; Kraatz, M.S., Ed.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2015; pp. 89–119. [Google Scholar]

- Deem, R.; Brehony, K.J. Management as ideology: The case of ‘new managerialism’ in higher education. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 2005, 31, 217–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgins, M.; Mannix-McNamara, P. The neoliberal university in Ireland: Institutional Bullying by Another Name? Societies 2021, 11, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deasy, C.; Mannix-McNamara, P. Challenging performativity in Higher Education: Promoting a Healthier Learning Culture. In Global Voices in Higher Education; Renes, S.L., Ed.; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2017; pp. 59–77. [Google Scholar]

- do Mar Pereira, M. Struggling within and beyond the performative university: Articulating activism and work in an ‘academia without walls’. Womens Stud. Int. Forum 2016, 54, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinchin, I.M. The salutogenic management of pedagogic frailty: A case of educational theory development using concept mapping. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bowers, C.A. How language limits our understandings of environmental education. Environ. Educ. Res. 2001, 7, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, M.L.; Van Kessel, G.; Sanderson, B.; Naumann, F.; Lane, M.; Reubenson, A.; Carter, A. Resilience in higher education students: A scoping review. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2019, 38, 1105–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wals, A.E. Sustainability in higher education in the context of the UN DESD: A review of learning and institutionalization processes. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 62, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prádanos, L.I. The pedagogy of degrowth: Teaching Hispanic studies in the age of social inequality and ecological collapse. Ariz. J. Hisp. Cult. Stud. 2015, 19, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoppek, D.E. How far is degrowth a really revolutionary counter movement to neoliberalism? Environ. Values 2020, 29, 131–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaufman, N.; Sanders, C.; Wortman, J. Building new foundations: The future of education from a degrowth perspective. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 931–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobulescu, R. Wake up. Managers, times have changed! A plea for degrowth pedagogy in business schools. Policy Futur. Educ. 2022, 20, 188–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noddings, N. The caring relation in teaching. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 2012, 38, 771–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duclos, V.; Criado, T.S. Care in trouble: Ecologies of support from below and beyond. Med. Anthr. Q. 2020, 34, 153–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratford, R. What Is the Ecological University and Why Is It a Significant Challenge for Higher Education Policy and Practice? PESA-Philosophy of Education Society of Australasia, ANCU: Melbourne, Australia, 2015; Available online: https://www.academia.edu/19661131 (accessed on 31 July 2022).

- Barnett, R. The Ecological University: A Feasible Utopia; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kinchin, I.M. Exploring dynamic processes within the ecological university: A focus on the adaptive cycle. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 2021, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Code, L. Ecological Thinking: The Politics of Epistemological Location; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Niemi, H. Building Partnerships in an Educational Ecosystem. Cent. Educ. Policy Stud. J. 2016, 6, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, C.; Lowan-Trudeau, G. Global politics of the COVID-19 pandemic, and other current issues of environmental justice. J. Environ. Educ. 2021, 52, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkovich, I. A socio-ecological framework of social justice leadership in education. J. Educ. Adm. 2014, 52, 282–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luckett, K.; Shay, S. Reframing the curriculum: A transformative approach. Crit. Stud. Educ. 2017, 61, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furman, G.C.; Gruenewald, D.A. Expanding the landscape of social justice: A critical ecological analysis. Educ. Adm. Q. 2004, 40, 47–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, G.; Habeshaw, T.; Yorke, M. Institutional learning and teaching strategies in English higher education. High. Educ. 2000, 40, 351–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clegg, S.; Smith, K. Learning, teaching and assessment strategies in higher education: Contradictions of genre and desiring. Res. Pap. Educ. 2010, 25, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, G.A. Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qual. Res. J. 2009, 9, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nicolini, D. Zooming in and zooming out: A package of method and theory to study work practices. In Organizational Ethnography: Studying the Complexities of Everyday Life; Ybema, S., Yanow, D., Wels, H., Kamsteeg, F., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2009; pp. 120–138. [Google Scholar]

- Nordmann, E.; Hutchison, J.; MacKay, J.R. Lecture rapture: The place and case for lectures in the new normal. Teach. High. Educ. 2021, 14, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, S.; Kennedy, G. Reassessing the value of university lectures. Teach. High. Educ. 2017, 22, 639–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerez, O.; Orsini, C.; Ortiz, C.; Hasbun, B. Which conditions facilitate the effectiveness of large-group learning activities? A systematic review of research in higher education. Learn. Res. Pract. 2021, 7, 147–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neilson, D.; Enright, N.F. From dead information to a living knowledge ecology. In Bioinformational Philosophy and Postdigital Knowledge Ecologies; Peters, M.A., Jandrić, P., Hayes, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 183–202. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, M.A. Digital socialism or knowledge capitalism? Educ. Philos. Theory 2020, 52, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- de Santos, B.S. Epistemologies of the South: Justice against Epistemicide; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, B.L.; Tandon, R. Decolonization of knowledge, epistemicide, participatory research and higher education. Res. All 2017, 1, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clegg, S. The necessity and possibility of powerful ‘regional’ knowledge: Curriculum change and renewal. Teach. High. Educ. 2016, 21, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, H.L. Transformative sustainability pedagogy: Learning from ecological systems and indigenous wisdom. J. Transform. Educ. 2015, 13, 259–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Manathunga, C.; Singh, M.; Bunda, T. ‘Histories of knowledges’ for research education. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2022, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosetti, L.; Walker, K. Perspectives of UK Vice-Chancellors on leading universities in a knowledge-based economy. High. Educ. Q. 2010, 64, 4–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olssen, M.; Peters, M.A. Neoliberalism, higher education and the knowledge economy: From the free market to knowledge capitalism. J. Educ. Policy 2005, 20, 313–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairchild, J.; Meiners, E.B.; Violette, J. “I Tolerate Technology-I Don’t Embrace It”: Instructor Surprise and Sensemaking in a Technology-Rich Learning Environment. J. Sch. Teach. Learn. 2016, 16, 92–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Josefsson, I.; Blomberg, A. Turning to the dark side: Challenging the hegemonic positivity of the creativity discourse. Scand. J. Manag. 2020, 36, 101088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, J.P.N. On the curation of negentropic forms of knowledge. Educ. Philos. Theory 2022, 54, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jandrić, P.; Knox, J.; Besley, T.; Ryberg, T.; Suoranta, J.; Hayes, S. Postdigital science and education. Educ. Philos. Theory 2018, 50, 893–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.; Bennett, R. Reaching beyond an online/offline divide: Invoking the rhizome in higher education course design. Technol. Pedagog. Educ. 2017, 26, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawns, T. An Entangled Pedagogy: Looking Beyond the Pedagogy—Technology Dichotomy. Postdigital Sci. Educ. 2022, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jandrić, P.; Hayes, S. Postdigital We-learn. Stud. Philos. Educ. 2020, 39, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gourlay, L. There is no ‘virtual learning’: The materiality of digital education. J. New Approaches Educ. Res. 2021, 10, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsui, A.B.M.; Tavares, N.J. The technology cart and the pedagogy horse in online teaching. Engl. Teach. Learn. 2021, 45, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinchin, I.M. Avoiding technology-enhanced non-learning. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2012, 43, E43–E48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilead, T.; Dishon, G. Rethinking future uncertainty in the shadow of COVID 19: Education, change, complexity and adaptability. Educ. Philos. Theory 2022, 54, 822–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketschau, T.J. Social justice as a link between sustainability and educational sciences. Sustainability 2015, 7, 15754–15771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clegg, S. The Demotic Turn–Excellence by Fiat. In International Perspectives on Teaching Excellence in Higher Education: Improving Knowledge and Practice; Skelton, A., Ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2007; pp. 91–102. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, T. Rethinking teaching excellence in Australian Higher Education. Int. J. Comp. Educ. Dev. 2019, 21, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesta, G. How useful should the university be? On the rise of the Global University and the crisis in Higher Education. Qui Parle 2011, 20, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C.; Carpenter, S.; Elmqvist, T.; Gunderson, L.; Walker, B. Resilience: Now more than ever. Ambio 2021, 50, 1774–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biesta, G.; Wainwright, E.; Aldridge, D. A case for diversity in educational research and educational practice. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2022, 48, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinchin, I.M.; Cabot, L.B. Reconsidering the dimensions of expertise: From linear stages towards dual processing. Lond. Rev. Educ. 2010, 8, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, I.B. Itinerant curriculum theory against epistemicides: A dialogue between the thinking of Santos and Paraskeva. J. Am. Assoc. Adv. Curric. Stud. 2017, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Paraskeva, J.M. ‘Did COVID-19 exist before the scientists?’ Towards curriculum theory now. Educ. Philos. Theory 2021, 54, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paraskeva, J.M. The generation of the utopia: Itinerant curriculum theory towards a ‘futurable future’. Discourse Stud. Cult. Politi-Educ. 2022, 43, 347–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winks, L.; Green, N.; Dyer, S. Nurturing innovation and creativity in educational practice: Principles for supporting faculty peer learning through campus design. High. Educ. 2020, 80, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ecton, W.G.; Dziesinski, A.B. Using punctuated equilibrium to understand patterns of institutional budget change in higher education. J. High. Educ. 2021, 93, 424–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, K.-L.D. Vectors of change in higher education curricula. J. Curr. Stud. 2022, 54, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, S.; Walker, B.; Anderies, J.M.; Abel, N. From metaphor to measurement: Resilience of what to what? Ecosystems 2001, 4, 765–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateson, G. Steps to an Ecology of Mind: Collected Essays in Anthropology, Psychiatry, Evolution, and Epistemology; Chandler Pub. Co.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Dakos, V.; Kéfi, S. Ecological resilience: What to measure and how. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 043003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinchin, I.M.; Winstone, N.E. (Eds.) Pedagogic Frailty and Resilience in the University; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoff, G.; Johnson, M. Metaphors We Live By; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gilstrap, D.L. Strange attractors and human interaction: Leading complex organizations through the use of metaphors. Complicity Int. J. Complex. Educ. 2005, 1, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sharpe, B.; Hodgson, A.; Leicester, G.; Lyon, A.; Fazey, I. Three horizons: A pathways practice for transformation. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Raudsepp-Hearne, C.; Peterson, G.D.; Bennett, E.M.; Biggs, R.; Norström, A.V.; Pereira, L.; Aceituno, A.J. Seeds of good anthropocenes: Developing sustainability scenarios for Northern Europe. Sustain. Sci. 2020, 15, 605–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Curry, A.; Hodgson, A. Seeing in multiple horizons: Connecting futures to strategy. J. Futur. Stud. 2008, 13, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Fazey, I.; Schäpke, N.; Caniglia, G.; Hodgson, A.; Kendrick, I.; Lyon, C.; Saha, P. Transforming knowledge systems for life on Earth: Visions of future systems and how to get there. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 70, 101724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brew, A.; Boud, D.; Lucas, L.; Crawford, K. Academic artisans in the research university. High. Educ. 2018, 76, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinchin, I.M.; Lygo-Baker, S.; Hay, D.B. Universities as centres of non-learning. Stud. High. Educ. 2008, 33, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misiaszek, G.W. Countering post-truths through ecopedagogical literacies: Teaching to critically read ‘development’ and ‘sustainable development’. Educ. Philos. Theory 2020, 52, 747–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misiaszek, G.W. Ecopedagogy: Teaching critical literacies of ‘development’, ‘sustainability’, and ‘sustainable development’. Teach. High. Educ. 2020, 25, 615–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hametner, M. Economics without ecology: How the SDGs fail to align socioeconomic development with environmental sustainability. Ecol. Econ. 2022, 199, 107490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickel, J. The contradiction of the sustainable development goals: Growth versus ecology on a finite planet. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 27, 873–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampietro, M.; Mayumi, K. Unraveling the complexity of the Javons Paradox: The link between innovation, efficiency, and sustainability. Front. Energy Res. 2018, 6, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nyborg, K.; Anderies, J.M.; Dannenberg, A.; Lindahl, T.; Schill, C.; Schlüter, M.; De Zeeuw, A. Social norms as solutions. Science 2016, 354, 42–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Institution | Title | Range | Page Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aston | Education strategy | 2021–2025 | 2 |

| Bath Spa | Education strategy | to 2030 | 1 |

| Bristol | Education strategy | 2017–23 | 9 |

| Cardiff | Education and students | 2018–2023 | 5 |

| Durham | University strategy | 2017–2027 | 32 |

| Edinburgh | Learning and teaching strategy | to 2030 | 7 |

| Essex | Education strategy | 2019–25 | 11 |

| Exeter | Education strategy | 2019–2025 | 16 |

| Glasgow | Learning and teaching strategy | 2021–2025 | 9 |

| Huddersfield | Teaching and learning strategy | 2018–2025 | 2 |

| Imperial | Learning and teaching strategy | Undated document | 42 |

| KCL | Education strategy | 2017–2022 | 30 |

| Lancaster | Education strategy | from 2020 | 7 |

| Manchester Metropolitan | Education strategy | to 2030 | 39 |

| Nottingham | Strategic delivery plan for education and student experience | 2021 onwards | 12 |

| Oxford Brooks | University strategy | 2020–2035 | 38 |

| Plymouth | Education and student experience strategy | 2018–2023 | 5 |

| Queen’s | Strategy | to 2030 | 11 |

| St. Andrews | Education strategy | 2020–2025 | 3 |

| Westminster | Education strategy | 2021–23 | 8 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kinchin, I.M. The Ecological Root Metaphor for Higher Education: Searching for Evidence of Conceptual Emergence within University Education Strategies. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 528. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12080528

Kinchin IM. The Ecological Root Metaphor for Higher Education: Searching for Evidence of Conceptual Emergence within University Education Strategies. Education Sciences. 2022; 12(8):528. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12080528

Chicago/Turabian StyleKinchin, Ian M. 2022. "The Ecological Root Metaphor for Higher Education: Searching for Evidence of Conceptual Emergence within University Education Strategies" Education Sciences 12, no. 8: 528. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12080528

APA StyleKinchin, I. M. (2022). The Ecological Root Metaphor for Higher Education: Searching for Evidence of Conceptual Emergence within University Education Strategies. Education Sciences, 12(8), 528. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12080528