Abstract

COVID-19 forced universities to shift to online learning (emergency remote teaching (ERT)). This study aimed at identifying the nontechnological challenges that faced Sultan Qaboos University medical and biomedical sciences students during the pandemic. This was a survey-based, cross-sectional study aimed at identifying nontechnological challenges using Likert scale, multiple-choice, and open-ended questions. Students participated voluntarily and gave their consent; anonymity was maintained and all data were encrypted. The response rate was 17.95% (n = 131) with no statistically significant difference based on gender or majors (p-value > 0.05). Of the sample, 102 (77.9%) were stressed by exam location uncertainty, 96 (73.3%) felt easily distracted, 98 (74.8%) suffered physical health issues, and 89 (67.9%) struggled with time management. The main barriers were lack of motivation (92 (70.2%)), instruction/information overload (78 (59.5%)), and poor communication with teachers (74 (56.5%)). Furthermore, 57 (43.5%) said their prayer time was affected, and 65 (49.6%) had difficulties studying during Ramadan. The most important qualitative findings were poor communication and lack of motivation, which were reflected in student comments. While ERT had positive aspects, it precipitated many nontechnological challenges that highlight the inapplicability of ERT as a method of online learning for long-term e-learning initiatives. Challenges must be considered by the faculty to provide the best learning experience for students in the future.

1. Introduction

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19), caused by the coronavirus known as SARS-CoV-2 [1], affected health professions education (HPE) around the world [2]. Most of the world’s universities and educational institutions were forced to change their methods of teaching: they stopped face-to-face teaching, and they depended upon remote or online teaching for students to continue learning and reduce academic disruption [3]. Although e-learning in general (including in medical education) is practiced around the world [4], the upheaval was caused by the sudden move to methods of teaching that were new to many people, including administrators, teachers, and students [5]. Unlike well-established e-learning practices that have been followed in the past [4], the online learning activities were best described as emergency remote teaching (ERT) [6], which focused on getting educational material to students and attempting to replicate face-to-face teaching and learning activities in an online world [7,8].

The literature indicates that adopting ERT as a method to teach medical students has many challenges, especially technological challenges, including poor internet connection and unavailable technology [8,9].

1.1. Nontechnological Challenges

In addition to technological challenges, however, nontechnological challenges were also faced by students during the pandemic; the most commonly highlighted have generally been classified as social [9], methodological [10], behavioral [9,10], and financial [11].

More specifically, the challenges included a lack of physical space conducive to studying [12,13], mental health issues [2,12,14], physical health issues [3,11,12], poor communication [2,12], time management [2,10], and maintaining motivation [15,16,17]. As this study deals exclusively with preclinical students, we have not included challenges involving patient interactions, which are discussed elsewhere [18].

In Oman, a study conducted at the International Maritime College in Oman indicated that some of the challenges that students faced in online teaching during the pandemic were inappropriate homework environments, lack of time management, and lack of online teaching and learning experience, as well as depression caused by the pandemic [19].

A search of the literature showed that, to date, no similar study about nontechnological challenges faced by medical and biomedical science students in Oman has been published.

1.2. Setting

The College of Medicine and Health Science (CoMHS) at Sultan Qaboos University (SQU) is one of two medical schools in Oman. Because of the pandemic, CoMHS adopted ERT starting on 14 March 2020 following the Supreme Committee’s regulations [20].

At SQU’s CoMHS, students have two possible degree paths: a medical doctor (MD) program that requires a minimum of six years (three preclinical (Phases I and II) and three clinical (Phase III) years) and a biomedical sciences (BMS) program that requires four years [21]. In order to facilitate the students’ use of electronic services during ERT, the CoMHS mostly used freely available software; where this was not possible, the CoMHS purchased home licenses for students.

1.3. Aim

The main aim of this study was to identify and evaluate the nontechnological barriers faced by preclinical MD and BMS students in their education during the COVID-19 pandemic.

1.4. Rationale

To date, no such study has been conducted at the SQU College of Medicine and Health Sciences (CoMHS). Our study will help to identify the nontechnological challenges encountered by CoMHS students. The results will contribute to finding appropriate methods for conducting future online learning at the university, and generalizable results will contribute to a global understanding of these issues.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Settings and Participants

This was a cross-sectional study based on a survey that was distributed to preclinical medical and BMS students enrolled at the CoMHS. Based on the enrolment figures at the time of the study, the total population was 730 students (605 preclinical medical students and 125 BMS students).

2.2. Study Instrument and Procedure

Apart from standard demographic data, the survey form (see Appendix A) was created by examining similar survey instruments researching challenges faced by students during COVID-19, as described in the literature [2,3,11,12,14,15,16]. Additional questions were added to reflect local circumstances. In particular, as Oman is a Muslim-majority country and students have specific religious duties, especially during the holy month of Ramadan, questions pertaining to these were added.

The study survey was reviewed and validated through face-validation by an expert, and it was reviewed by the research team before it was distributed to the students. The final form contained 26 questions divided into four categories: demographics, personal, teachers/administration, home/social, and assessment as Likert scale (1–5) and multiple-choice questions, as well as open-ended (free-text) boxes asking for further comments and explanations about how identified barriers affected the students’ education so that we might gain deeper insight into the students’ experiences through qualitative data.

Ethical approval was obtained from (blinded for review). All the data obtained from the survey were encrypted using VeraCrypt (IDRIX) (Ver. 1.24). The survey notification and link were distributed to the students via their university email, Facebook, and student WhatsApp groups. The study survey was conducted electronically using Google Forms from August 2021 until December 2021. All the participants gave consent to be part of the study, completing a consent form that appeared to each participant before completing the survey. Participants who did not consent were thanked and moved to the end of the survey.

2.3. Data Analysis

The quantitative data obtained from the study were captured and analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) from the International Business Machines Corporation (IBM) (Ver. 23) and Microsoft Excel (Microsoft 365), and they were displayed in tables. Qualitative data were themed following inductive thematic analysis [22] and thematic networking [23] through QDAMiner Lite (Ver. 2.0.6). Theming was performed by one author (XX), and then independently verified by the other (YY). Discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Data

Out of 730 students, a total of 131 (17.95%) responded to the survey. Of these, 118 (90.1%) were MD students and the remaining 13 (9.9%) were BMS students. There were 69 (52.7%) females and 60 (45.8%) males; the remaining preferred not to state a gender. Table 1 shows the demographics of the respondents.

Table 1.

Demographic details of the respondents (n = 131).

For quantitative data analysis, a Chi-square test was used to check for any significance based on major or gender, where a p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All p-values were higher than 0.05, so no statistically significant differences were found. After adjusting for positively and negatively phrased questions, the Cronbach’s alpha value for the survey was α = 0.76.

Table 2 shows the student responses to questions. For ease of reporting, Likert scale items 1 and 2 (Strongly Disagree and Disagree) and 4 and 5 (Agree and Strongly Agree) have been combined.

Table 2.

Number of responses put to students with a Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Neutral, 4 = Agree, 5 = Strongly Agree) (N = 131).

In Table 2, a number of items stand out from the others, notably distractions, health-related challenges, and examination stress because of uncertainty. In addition, although the amount of time appeared sufficient, managing it proved difficult.

In addition, when asked whether they had financial issues during the pandemic, 99 (75.6%) students answered “No”, and 32 (24.4%) answered “Yes”.

Finally, the specific barriers identified by the students are given in Table 3 (numbers total more than 100% because more than one option could be chosen).

Table 3.

Specific barriers identified by the students (n = 131).

From Table 3, it can be seen that motivation coupled with poor communication and instruction/information overload appeared to be the prime barriers.

3.2. Qualitative Data

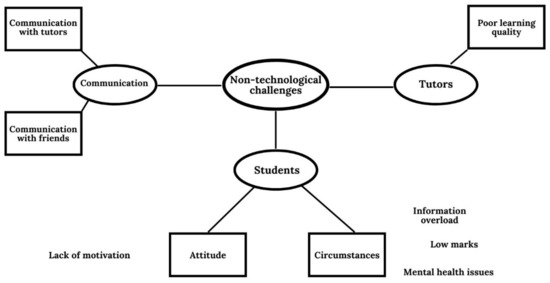

The quantitative data were supported by the qualitative data. The qualitative data were divided into three main themes: communication, tutors, and students, each with their main subthemes.

All comments below are reproduced verbatim, with some contextual information supplied (identifying label, geographical location, phase, gender).

3.2.1. Theme: Communication

The most important challenge that faced students was communication with tutors.

Some tutors were not replying to our emails (or at least not as soon as possible, but after more than 3 days) which makes us less encouraged to ask about anything because we might not get an answer.(S108, Rustaq, MD Phase One, Female)

As we are far from tutors, poor communication affected me because I couldn’t ask the tutors directly and some tutors did not respond at all to my emails.[S122, Bid Bid, MD Phase Two, Male]

The communcation with the instructors was a suffer with some and even cost me to lose marks and a drop in the GPA.(S42, Ibri, MD Phase One, Male)

Another communication challenge that was reported by students was communication with friends.

losing opportunity to contact face to face and make discussions with some friends about some info related to the lectures or something like that(S8, Bid Bid, MD Phase Two, Male)

The poor communication with the tutors and friends made it difficult to not be distracted and lost.(S33, Barka, MD Phase Two, Female)

3.2.2. Theme: Tutors

Students reported that poor learning quality was a challenge they faced during online learning.

Not to mention the awful quality of some lectures and the poor teaching methodology that was followed for the tutorials and practicals.(S47, Muscat, MD Phase Two, Female)

Learning online was quite difficult firstly because of the method of teaching, it was basically about opening a powerpoint and reading it out loud for students (not all Doctors obviously but the majority) and thus we didn’t really learn the information or grasp it the way we are supposed to, causing a strong lack of motivation I felt like I didn’t learn compared to the real lectures that were in the MLT.(S82, Muscat Al Seeb, MD Phase Two, Female)

3.2.3. Theme: Students

This theme was divided into two major subthemes: attitude and circumstances.

For attitude, lack of motivation was the most frequently reported obstacle.

Lack of motivation because you suffer alone, you don’t see your colleagues and share information and ideas with them and motivate each other.(S35, Ibra, MD Phase Two, Female)

Most of the time, I lost interest and motivation to continue studying due to the repetitive nature of online education, the long ppt lectures and the countless times I had to wake up early for an online live session and how monotonous the sessions are usually held.(S111, Salalah, MD Phase Two, Male)

Being away from the eductional institutions have effected my motivational levels because of feeling alone during the process of learing with no physcial interactions with the environment (like the ones that found in the college campus).(S42, Ibri, MD Phase One, Male)

Regarding circumstances, information overload, low marks, and mental health issues were common challenges that students reported.

There were too many instructions and information which need more time and more effort(S41, Sur, BMS year Two, Female)

The amount of information given was huge instructors might give a lot of whole new information in every time we have tutorials or even sessions for questions along with the informations from the books and honestly that is too much.(S108, Rustaq, MD Phase One, Female)

in addition to the overload of information everything was overwhelming(S80, Muscat, MD Phase Two, Female)

Students also reported that online learning affected them by getting low marks.

and in the end we lost a lot of marks and the GPA went down.(S99, Al-Mussanah, MD Phase Two, Female)

My GPA went down(S81, Muscat, MD Phase Two, Female)

In bad way…my mark down and no time to take breath(S18, Alsharqia, MD Phase One, Female)

Mental health issues were also a major challenge that students thought to be a consequence of online learning.

It puts us under a lot of pressure especially since we can’t switch between questions and it always makes us nervous and worried about enough time and sudden network outages(S99, Al-Mussanah, MD Phase Two, Female)

Due to having to stay for a long time at home and not being able to meet part of my family and friends this really messed up my psychological part and my motivation(S80, Muscat, MD Phase Two, Female)

All of the above let us feel depressed and useless(S118, Mahdha, MD Phase Two, Male)

Figure 1, following thematic networking [23], summarizes the qualitative data themes and subthemes mentioned.

Figure 1.

A summary of the main qualitative data themes, following thematic networking [23].

The qualitative data supplied a useful context for the quantitative data. In particular, they demonstrated the impact of poor communication and teaching materials on student motivation.

4. Discussion

This study identified the nontechnological challenges that SQU’s CoMHS students encountered during the COVID-19 pandemic, with both quantitative and qualitative data from a survey that was distributed to the students.

Although ERT allowed medical education to continue, and international studies have indicated benefits to students [3,10,12,24], the focus of this study was to identify the nontechnological challenges faced by students learning through ERT during the COVID-19 pandemic. In summary, the most important challenges can be classified as: distractions, physical and mental health-related challenges, time-related challenges, communication, quality of teaching materials, assessment, motivation, and two new local challenges related to prayer time and studying during Ramadan.

Similar to the findings of Kohan et al. [25] and Sawarkar et al. [3], more than two-thirds (mean: 4.02; SD: ±1.23; med: 4) of these students felt easily distracted during ERT. This might be explained by the students studying at home with other family members, which might create noise and disturbance, the perceived boring nature of ERT, and students not having a suitable environment for studying.

This study showed that headaches and eye strain were some of the physical health issues affecting students (mean: 4.04; SD: ±1.09; med: 4); this might be related to the students spending long hours in front of their devices while studying and attending lectures, which has also been reported by other researchers [3,11,12,13], who reported a lower percentage of students with physical health issues.

Mental health issues were also prevalent: SQU students reported, through open-ended questions, that issues like feeling anxious, stressed, pressured, depressed, or useless impacted their well-being. A possible explanation for these feelings is students not being able to meet with their colleagues and friends, as well as the continuous bad news about the impact of COVID-19 being shared everywhere, which has also been found in several other studies [2,12,14].

Although the online learning experience was new for SQU students, they appeared to have no problems with preparation time, as the majority said that online learning needed an acceptable amount of preparation time (mean: 3.82; SD: ±1.12; med: 4), similar to what was found in [15]. That said, however, because of the change in the teaching method and the environment in which students studied, the students’ main problem was managing their time (mean: 3.95; SD: ±1.27; med: 4). Although other studies have also found this [2,10], the 68% found in our study is appreciably higher than reported elsewhere (e.g., Rajab et al. [2] reported that 35% of students had issues with time management).

In addition to changes in teaching methods, assessment (especially proctored examination) methods also changed during ERT. SQU CoMHS students were stressed because of examination location uncertainty and felt that the examination process during ERT did not provide fair assessment (mean: 2.37; SD: ±1.20; med: 2); similar challenges were reported by Rajab et al. [2] and Farooq et al. [17].

Prayer time was one of the important local aspects studied in this article, and almost half of the respondents reported that ERT affected their prayer time (Mean: 3.05; SD: ±1.41; Med: 3). Because the students were studying from home, there would be tension between on-campus rules (such as the inability to have prayer breaks during the lecture) and expectations in the home environment.

Similarly, another local challenge encountered by students was studying during the month of Ramadan (mean: 3.40; SD: ±1.36; med: 3). Being at home during Ramadan, students may have more family commitments than they would have on campus, and so this change in routine led to extra difficulties in learning during Ramadan.

In contrast with a study by Alsoufi et al. [11], which found that 40.5% of the students suffered from financial problems and as many as 78% had trouble accessing their e-learning because of financial problems, only 24% of the students in this study reported financial problems. Part of this large difference may be, however, because the Alsoufi et al. study was conducted in Libya, and their students had been affected by conflicts, whereas Oman is relatively politically stable. In addition, medical students at SQU already had and used electronic devices required for online learning prior to the pandemic [26] and did not need to acquire new devices. Finally, the CoMHS provided the students with the software needed for online teaching without having students purchase it.

As Tuma et al. mentioned in their study [15], 67% of the students lost interest and felt tired during online learning, which is almost the same percentage reported by CoMHS students during ERT. Means et al. [13] also mention that motivation was a challenge for 42% of the students. A study by Shawaqfeh et al. [16] also showed that student motivation was negatively affected during online learning. Our qualitative data shed light on this issue, with students complaining about being unable to meet colleagues, the repetitive nature of online education, and long lectures.

In addition to poor motivation, the two greatest areas of concern were poor communication with tutors and instruction/information overload, faced by 55–60% of CoMHS students, a situation also found in other studies [9,12,24,25]. From the students’ qualitative comments, poor communication emerged because of tutors not replying to emails or replying late, which made it difficult to communicate (as compared to face-to-face learning where there is usually more direct contact and interaction with tutors). The qualitative comments in the results show also that the poor quality of teaching materials was frequently noted by students, and this contributed to the instruction/information overload.

Unfortunately, this was to be expected. For more than 40 years, especially in the work of John M Keller, instructional designers have been aware of the impact of poorly crafted materials on student motivation [27], and Keller’s ARCS Model [28] has been applied and verified innumerable times in medical education (e.g., [29]). Similarly, quality interaction with tutors also has a direct impact on student motivation [30]. Given the nature of ERT and its focus on getting teaching material to the students [6], the worldwide impact of ERT was an attempt at replicating face-to-face interactions but with very little reference to online learning theory or best practices [8]. The nature of ERT demands very little support and planning for teachers, and this was reflected in the problems facing the students. While unfortunate, the literature shows that the stresses suffered by the teaching staff are not unique to SQU [31,32], but, for the most part, ERT is considered a better choice than the alternative of stopping education entirely.

4.1. Implications for Online Education

Like other institutions around the world, SQU had previously identified e-learning as a strategic area of development [33]. Although e-learning initiatives were ongoing, the pandemic galvanized the processes, allowing students and staff to experience aspects of e-learning. As is clear from the literature [4,6,7,8], however, ERT is not standard e-learning, and the problems identified in this study were frequently a result of the emergency, which serve as a valuable reminder that good-quality online learning does require thorough planning and long-term strategies.

4.2. Limitations

It was noted in this study that most of the responses were from MD students, with a low response rate from BMS students. Among the MD students, more responses from “Phase II” students were noted than from “Phase I” students. In addition, this study was conducted at one college at one institution; given the similarities between the student experiences described in the literature, however, we feel that the results are of value to other institutions.

5. Conclusions

Although ERT permitted education to continue and, thus, benefitted students, this study aimed to identify the nontechnological challenges that faced SQU CoMHS students during the COVID-19 pandemic. The sudden shift from face-to-face learning due to ERT precipitated many challenges, the most important of which were being distracted, physical and mental health-related challenges, time-related challenges, assessment, prayer time being affected, difficulty studying during Ramadan, maintaining motivation, and communication. By identifying these problems, this study adds to the body of knowledge, providing valuable data for institutions that are planning to move their courses into the online environment. There is, no doubt, a need for further investigation, recommendations, and solutions so that students can achieve better results from online teaching and learning in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K.A. and K.M.; methodology, A.K.A. and K.M.; validation, K.M.; formal analysis, A.K.A. and K.M.; investigation, A.K.A.; resources, A.K.A. and K.M.; data curation, A.K.A. and K.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.K.A.; writing—review and editing, K.M.; visualization, A.K.A. and K.M.; supervision, K.M.; project administration, K.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Sultan Qaboos University College of Medicine and Health Sciences Medical Research Ethics Committee (MREC #2527, 25 July 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available because the participants did not agree for their data to be shared publicly.

Acknowledgments

Our gratitude to CoMHS Administration Staff, for supplying details about student numbers registered students’ representatives for help in distributing the survey, and to the students who participated in the survey.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

The Questionnaire.

Table A1.

The Questionnaire.

| Question NO. | Question |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| 1 | What is your gender? (Male, Female, Prefer not to say, Other) |

| 2 | What is your major (MD or BMS)? (MCQ) |

| 3 | In what were you in SPRING 2021? (Foundation year, MD Phase one, MD Phase two, Intercalated Year, BMS year one, BMS year two, BMS year three, BMS year four, other) |

| 4 | In which Wilayat or City you live? (Free text box) |

| Personal | |

| 5 | I have suffered from financial problems related to the pandemic. (Y/N) |

| 6 | Using online teaching technology needed an acceptable amount of preparation time and effort. (SDA/DA/N/A/SA) |

| 7 | I felt tired and I lost interest from doing all the teaching online (SDA/DA/N/A/SA) |

| 8 | I had more difficulties in learning through online than face to face traditional learning (SDA/DA/N/A/SA) |

| 9 | I felt easily distracted during online learning. (SDA/DA/N/A/SA) |

| 10 | The time spent in front of my devices caused me headaches and eye strain. (SDA/DA/N/A/SA) |

| 11 | Time management was a challenge. (SDA/DA/N/A/SA) |

| 12 | The following were real barriers to my e-learning process: (SA/A/N/DA/SDA) Lack of past experience on using online tools. Lack of motivation. Lack of instructions. Living away from educational institutions. Poor communication with teachers. Instruction/Information overload Other Nontechnical challenges: Please give details (text box) |

| 13 | Please explain how these barriers affected your education (Free text box) |

| Teachers/Administration | |

| 14 | On the whole, the instructions given by the teaching staff were clear (SDA/DA/N/A/SA) |

| 15 | The expectations and objectives of the teaching activities were achieved (SDA/DA/N/A/SA) |

| Home/social | |

| 16 | Overall, my current living arrangements are conducive to remote learning. (SDA/DA/N/A/SA) |

| 17 | I have sufficient access to quiet study space to meet the demands of remote learning. (SDA/DA/N/A/SA) |

| 18 | During online learning, I had more chores and family commitments. (SDA/DA/N/A/SA) |

| 19 | Online learning affected my prayer time. (SDA/DA/N/A/SA) |

| 20 | I found it difficult to study during Ramadan time. (SDA/DA/N/A/SA) |

| 21 | I still feel connected to my classmates. (SDA/DA/N/A/SA) |

| Assessments | |

| 22 | I feel that the examination process provides a fair assessment. (SDA/DA/N/A/SA) |

| 23 | I felt stressed for no knowing how I am going to be examined (Whether online or on campus). (SDA/DA/N/A/SA) |

| 24 | It was hard to find a place to stay in during the time of final exams. (SDA/DA/N/A/SA) |

| 25 | Studying at home is harder because of the noises or interruptions. (SDA/DA/N/A/SA) |

| 26 | Any comments on the topic? (Free text book) |

Note: Designed by authors Abdulmalik Khalid Alshamsi and Ken Masters, using 5 point likert scale: Strongly Disagree, Disagree, Neutral, Agree, Strongly Agree.

References

- WHO. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19). 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/coronavirus-disease-covid-19 (accessed on 23 March 2021).

- Rajab, M.H.; Gazal, A.M.; Alkattan, K. Challenges to Online Medical Education during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Cureus 2020, 12, e8966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawarkar, G.; Sawarkar, P.; Kuchewar, V. Ayurveda students’ perception toward online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2020, 9, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellaway, R.; Masters, K. AMEE Guide 32: E-Learning in medical education Part 1: Learning, teaching and assessment. Med. Teach. 2008, 30, 455–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, S.; Gatto, R.; Fabiani, L. Effects of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on medical education in Italy: Considerations and tips. EuroMediterr. Biomed. J. 2020, 15, 100–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, C.; Moore, S.; Lockee, B.; Trust, T.; Bond, A. The Difference Between Emergency Remote Teaching and Online Learning. 2020. Available online: https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-difference-between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-online-learning (accessed on 28 January 2021).

- Daniel, M.; Gordon, M.; Patricio, M.; Hider, A.; Pawlik, C.; Bhagdev, R.; Ahmad, S.; Alston, S.; Park, S.; Pawlikowska, T.; et al. An update on developments in medical education in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: A BEME scoping review: BEME Guide No. 64. Med. Teach. 2021, 43, 253–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojan, J.; Haas, M.; Thammasitboon, S.; Lander, L.; Evans, S.; Pawlik, C.; Pawilkowska, T.; Lew, M.; Khamees, D.; Peterson, W.; et al. Online learning developments in undergraduate medical education in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: A BEME systematic review: BEME Guide No. 69. Med. Teach. 2021, 44, 109–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboagye, E.; Yawson, J.A.; Appiah, K.N. COVID-19 and E-Learning: The Challenges of Students in Tertiary Institutions. Soc. Educ. Res. 2021, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, R.; Mansour, A.E.; Fadda, W.A.; Almisnid, K.; Aldamegh, M.; Al-Nafeesah, A.; Alkhalifah, A.; Al-Wutayd, O. The sudden transition to synchronized online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia: A qualitative study exploring medical students’ perspectives. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsoufi, A.; Alsuyihili, A.; Msherghi, A.; Elhadi, A.; Atiyah, H.; Ashini, A.; Ashwieb, A.; Ghula, M.; Hasan, H.B.; Abudabuos, S.; et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical education: Medical students’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding electronic learning. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0242905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baticulon, R.E.; Alberto, N.R.R.; Baron, M.B.C.; Mabulay, R.E.E.; Rizada, L.G.G.; Sy, J.J.; Tiu, C.J.S.; Clarion, C.A.; Reyes, J.C.B. Barriers to online learning in the time of COVID-19: A national survey of medical students in the Philippines. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Means, B.; Neisler, J.; Associates, L.R. Suddenly Online: A National Survey of Undergraduates During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Digit. Promise 2020. Available online: https://digitalpromise.dspacedirect.org/handle/20.500.12265/98 (accessed on 23 March 2021).

- Shahrvini, B.; Baxter, S.L.; Coffey, C.S.; MacDonald, B.V.; Lander, L. Pre-clinical remote undergraduate medical education during the COVID-19 pandemic: A survey study. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuma, F.; Nassar, A.K.; Kamel, M.K.; Knowlton, L.M.; Jawad, N.K. Students and faculty perception of distance medical education outcomes in resource-constrained system during COVID-19 pandemic. A cross-sectional study. Ann. Med. Surg. 2021, 62, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shawaqfeh, M.S.; Al Bekairy, A.M.; Al-Azayzih, A.; Alkatheri, A.A.; Qandil, A.M.; Obaidat, A.A.; Al Harbi, S.; Muflih, S.M. Pharmacy Students Perceptions of Their Distance Online Learning Experience During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Survey Study. J. Med. Educ. Curric. Dev. 2020, 7, 2382120520963039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, F.; Rathore, F.A.; Mansoor, S.N. Challenges of Online Medical Education in Pakistan During COVID-19 Pandemic. J Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. JCPSP 2020, 30, 67–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, S. Medical Student Education in the Time of COVID-19. JAMA 2020, 323, 2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slimi, Z. Online learning and teaching during COVID-19: A case study from Oman. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Lang. Stud. IJITLS 2020, 4, 44–56. [Google Scholar]

- Times Of Oman. Oman Takes tough Measures to Tackle Coronavirus. Times of Oman. 2020. Available online: https://timesofoman.com/article/2909323/oman/oman-takes-tough-measures-to-tackle-coronavirus (accessed on 18 March 2021).

- SQU. College of Medicine and Health Sciences > Programs > Undergraduate. 2021. Available online: https://www.squ.edu.om/medicine/-Programs/Undergraduate (accessed on 18 March 2021).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attride-Stirling, J. Thematic networks: An analytic tool for qualitative research. Qual. Res. 2001, 1, 385–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Balas, M.; Al-Balas, H.I.; Jaber, H.M.; Obeidat, K.; Al-Balas, H.; Aborajooh, E.A.; Al-Taher, R.; Al-Balas, B. Distance learning in clinical medical education amid COVID-19 pandemic in Jordan: Current situation, challenges, and perspectives. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohan, N.; Soltani Arabshahi, K.; Mojtahedzadeh, R.; Abbaszadeh, A.; Rakhshani, T.; Emami, A. Self-directed learning barriers in a virtual environment: A qualitative study. J. Adv. Med. Educ. Prof. 2017, 5, 116–123. [Google Scholar]

- Masters, K.; Al-Rawahi, Z. The use of mobile learning by 6th-year medical students in a minimally-supported environment. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2012, 3, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Keller, J.M. Motivation and Instructional Design: A Theoretical Perspective. J. Instr. Dev. 1979, 2, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, J.M. Development and use of the ARCS model of instructional design. J. Instr. Dev. 1987, 10, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, D.A.; Beckman, T.J.; Thomas, K.G.; Thompson, W.G. Measuring Motivational Characteristics of Courses: Applying Keller’s Instructional Materials Motivation Survey to a Web-Based Course. Acad. Med. 2009, 84, 1505–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Song, H.-D.; Hong, A. Exploring Factors, and Indicators for Measuring Students’ Sustainable Engagement in e-Learning. Sustainability 2019, 11, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, A.; Durning, S.J.; Larsen, K.L. Transition to online teaching with self-compassion. Clin. Teach. 2020, 17, 538–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masters, K. They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? A warning to medical schools about medical teacher burnout during COVID-19. MedEdPublish 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SQU. SQU Strategic Plan, 2016–2040; Sultan Qaboos University: Al-Khoud, Oman, 2015. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).