Abstract

The advance and influence of neoliberalisation processes has changed the way of understanding and managing the educational system under a New Public Management (NPM) of education that integrates the values of the free market, competitiveness, accountability, external evaluation, etc. The objective of this work is to analyse Andalusian headteachers’ perceptions of their professional practices from within the context of neoliberal and neo-conservative processes. The methodology used is based on a qualitative research approach, where we analyse the implications of neoliberal processes and NPM in the school principalship in Andalusia (Spain). The sample of participants was consolidated into 15 principals belonging to public high schools. For data collection, in-depth interview was used. Information analysis applies content analysis and its assembly with the grounded theory. The results are expressed in four categories that refer to the implications of neoliberal processes and NGP in the school principalship. There is a tendency to redefine the role of the headteacher as a manager. The discussion and conclusions point out how the neoliberal processes and the NPM are reconfiguring the school principalship towards a “manager-administrator” profile, a management instrument with administrative functions and an agent for assessment in the school. In this context, there are also processes of confrontation and discomfort with these transformations in the principal’s role.

1. Introduction

The main objective of this work is to analyse Andalusian headteachers’ perceptions of their professional practices from within the context of neoliberal and neo-conservative processes. Taking this objective as a reference point, this paper is structured in a series of interconnected sections. In the first section, neoliberalisation processes are explored from a global perspective, and their impact on state educational systems, in addition to the construction of neoliberal subjectivities, is analysed. In the second section, the keys to the “good governance” of schools from the perspective of New Public Management (NPM) are analysed from comparative and global perspectives. In the third section, the focus is on the neo-conservative character of state educational policies, introduced in recent years in Spain by the Popular Party (PP).

Starting from this conceptual and analytical framework, the following sections aim to make a contribution from a critical and constructivist theory of reality, which is very different from the research, which focused on the competences and technical skills of school leaders [1]. In addition, the interpretation of the perceptions, valuations and beliefs which support these abilities (technical, personal, professional, etc.) are analysed. In terms of this approach, context matters. This is because the profession of headteaching reflects the influence of the historical, cultural and political environment [2]. This explains and supports the use of the interpretive approach, which allows it to connect with the professional practice, as the narrative is a resource which reproduces experiences and gives coherence (meaning) to the testimonies collected in the field work [3].

This study combines the interpretive approach with a narrative dimension, evidencing not only the link with practice but also creating spaces for questioning and problematisation (resistance). The task of relating the empirical content (emic) to the theoretical foundation (etic) has enabled us to observe, with more clarity, the power relations and flows which exist within neoliberal governance mechanisms.

1.1. Processes of Neoliberalisation and Construction of Subjectivities

Using this framework, the analysis of neoliberal processes and their implications for the field of education policy are approached, specifically relating to the impact of the “new governance” (New Public Management) on those who manage schools subsidised by state funds. In this line, this study is linked to an approach to “neoliberalism” which places it as a multifactorial and multidimensional phenomenon with its own rationality [4], one which transcends the margins of the economic and market fields. The construction of neoliberal subjectivity makes life look from the lens of business logic. Public resources are analysed under this lens, so the “good governance” of the school is measured in terms of efficiency, effectiveness and economy. This means assuming neoliberalism as a form of school management in which some principals assume the characteristic values of accountability and business corporate responsibility (the school has to be managed as if it were another business company), among others, developing resistance practices.

Much of the academic work which has been carried out during the last few decades has centred on the analysis of neoliberal processes. Researchers, such as those in [5], argue that we are facing a multiform phenomenon which strongly conditions our way of being and seeing the world. For Brown, neoliberalism, as an intellectual project, is something more complex than a simple interest in and way of accumulating global capital. Although it relies on a rationality which strengthens the power of the capitalist class, it is a (political) rationality which goes beyond the economic concept of “market”. This project redefines global governance, giving new meaning to the relationships which exist between the state, economy, society, and citizens [6]. From the approach of New Public Management (NPM), individuals are seen in terms of human capital (i.e., as a potential form of productivity). In this way, “market values” are being accepted, integrated and subjectivated [7]. Thus, democracy, as a space for equality, sovereignty and community interest, is vulnerable to those forms of neoliberal appropriation that recast its meaning and value [8].

According to the author of [5], one of the key tenets of neoliberalism which is not usually taken into account is “its powerful erosion of liberal democratic institutions and practices”. Eventually, democracy is hijacked by neoliberalism by giving it a new identity and a powerful rationality, which subjects come to see as something normal and natural. It shapes their worldviews and “legitimises” social inequality, seeing it as something “fair and necessary”. In other words, the neoliberal rationality fundamentally perceives social imbalances as a product of “free competition” and the survival of the fittest. Therefore, it is the subject herself or himself who is blamed for her or his failure (or incompetence). In this way, the social differences existing at the start, as well as the structural violence of the system which contributed to his or her failure, remain imperceptible and hidden in the shadows (name deleted to maintain the integrity of the review process, 2017).

The author of [8], referring to this discourse on education, suggests that “In recent decades, neoliberal policies have placed emphasis on competition between schools and NPM strategies as mechanisms which aim to improve state school performance and accountability in many countries.” Therefore, one of the central arguments put forward by NPM relates to the improvement of educational performance, which requires not only “competent” and “well-disciplined” teachers, but also efficient managers (the headteachers) who are accountable to the school administration as well as to society in general. In the words of [9], “the NPM has replaced bureaucratic modes of governance with the values of the private sector, in which the control of output, performance and efficiency is afforded much greater significance than either inputs or processes”. From this perspective, private providers offer different educational services to state schools. These include data management and programmes aimed at the professional development of teachers together with diagnostic tests, such as PISA. PISA has now become an increasingly common and socially legitimate mechanism for accountability within the state educational system.

Through NPM, the processes of privatisation and externalisation, as well as trade liberalisation and individual freedom, have been implemented under the banner of “encouraging human welfare” [10]. The authors of [7] hold that countries such as Chile, Spain, France, Italy, Norway and the United Kingdom have been implementing NPM reforms for a number of years. Under the OECD guidelines, these countries are now implementing school autonomy, together with accountability measures in line with the educational policy of NPM.

From a Foucaultian perspective, nation states play an active role in the configuration of this rationality, producing and reproducing the processes of NPM and constructing their own particular identity, in addition to guiding and making sense of public institutions like schools. This is in line with the “values” of business, competition and efficiency. The powers of the state also create this neoliberal reality. It is not only imposed by international institutions.

From within this context the NPM is redefining the role which different school actors, including headteachers, are expected to play. Culture is integrated and the methods and values of private interest have now infiltrated the heart of the public sector [11].

Neoliberal logic “makes us”, and it influences our thinking patterns in addition to our daily practices and tasks, which imitate the control mechanisms of private companies. In other words, it is the individual who “self-disciplines” herself or himself. This has been referred to as the keys to a “government at a distance” in [12] and by others, and it means that individuals control themselves without the need for direct control from outside, or at least visible control. This idea resonates with what was identified in [13] as one of the keys to the new government: “action at a distance”. It is a novel form of rationality which perceives governance in education through indirect forms of control under a mantra which sees economic market values as a way of improving performance. The neoliberal identity of the “entrepreneurial self” or the “entrepreneur of oneself” shapes a way of life. This is characterised by the need for permanent conquest, a strong utilitarian vision of nature and people, together with strong personal discipline. In another work (name deleted to maintain the integrity of the review process, (2016)), it is held that individuals construct a subjectivity which makes them see life as a “business”, operating in a similar way to the management of a company. As a result, individuals become “entrepreneurs of the self”. They conduct their lives in a competitive way and make endless demands on themselves, reviewing and reconstructing their own human capital.

1.2. The Keys to the “Good Governance” of Schools and New Public Management (NPM)

In the state education systems of Western countries such as Spain, discourses on “good governance” form part of the logic of performance control. Here, the professional performance of teachers and headteachers is analysed in terms of accountability and assessment [14]. There now exists a system which seeks to impose discipline in schools, with a particular focus on controlling the actions and performance of headteachers. This is a way of understanding educational governance which adopts business strategies for the control of both the financial performance and educational efficiency of the school [15].

It is argued in [16] that school headteachers have been given various tools in order to discipline their teaching staff. This is a control mechanism promoted by the aforementioned NPM. However, this form of control is concealed by the increase in an apparent (or theoretical) form of “school autonomy” in addition to a debate about the proper management of school governance. Different practices and programmes can be found under the umbrella of school autonomy. These range from managerial approaches (“school-based management”), whereby the headteacher assumes and exercises the functions of a business manager—hiring or firing teaching staff, raising funds for the school and managing its resources—to a more pedagogical and educational approach, whereby teachers are given more freedom to decide on important issues such as setting up school projects or devising curricular contents. Thus, teachers are perceived as autonomous professionals who make decisions according to their social context.

Neoliberal governance, which promotes this discourse, defends its position by holding that, if the training of school headteachers is improved in terms of management (under the heading “professionalism”), the performance of schools could be even better assessed [16].

This “updated” form of public-c sector management has been described by authors, such as Ball [11], as “neoliberal governance”. Ball argues that there has been a step from government to governance. In other words, there has been a redistribution of authority and the control and management of state schools. However, the analysis is not limited to school governance. The broader term of education governance and its relationship with NPM and neoliberalism in general are also highlighted.

According to [17], education governance is a broad and multifaceted concept. Unlike school governance, education governance is configured as a polyvalent phenomenon. Moreover, it can be conceived as a political-economic project or strategy, a form of intervention, a problematisation, empowerment or a persuasive technique.

In line with this, the authors of [18] perceive governance as “the new way to govern individuals and their behaviours, basically through three elements: the de-statalisation, ‘remote government’ and freedom-responsibility.” First, in the educational field, this approach to governance indicates that from the 1990s to the present, European states have no longer been the only ones responsible for state education. States favour the introduction of private providers, companies, foundations and think tanks, which now have the capacity to design programmes, transmit knowledge and manage educational centres.

Due to this, and within a framework of educational reform, education governance facilitates institutional dynamics and practices which dismantle intermediate structures, activities and government agents and transfer more alleged “power” or “autonomy” to schools [11]. This decentralisation or “disintermediation” [19] intensifies the responsibilities of other agents, such as school inspectors and headteachers, while increasing the government’s concern about the suitability of schools. They are now expected to undertake duties and responsibilities related to assessment, control and accountability. From another perspective, education governance modifies traditional political structures and processes, making way for new agents which intervene with and benefit from public policies.

“Remote government” is another important element relating to this issue. This mode of governance combines more direct, personal, autonomous and horizontal methods of control behaviour with the traditional ones by means of direct, bureaucratic and hierarchical measures, similar to the quasi-market policy [20]. The assessment of educational results is a clear example of remote government. This is because the need to obtain positive educational results significantly conditions what both teachers and headteachers do or fail to do (meaning the impact of PISA reports, the pressure of rankings, etc.).

In line with this idea of remote government, education governance is seen as a technology based on distrust [13]. Its objective is to exert (remote) control on educational professionals and their teaching practices. An increase in school inspections, managerial deference, external monitoring and accountability can account for this [21]. As the authors of [21] hold, these processes “attract” people (through mediation and intermediation relationships) to participate in education governance and integrate methods of self-government and remote management.

Finally, the issue of freedom-responsibility feeds into this debate. This neatly connects with the vision of neoliberal rationality in [11], in which it is held that neoliberalism “makes us”. This also connects with the concept of “decentred governance” in [7], where this form of governance starts with an analysis of the behaviour patterns of the subjects and how they interpret the facts of everyday life, rather than analysing external structures or causes. In other words, individuals are expected to govern themselves. For example, in the educational field, the concept of school autonomy is penetrating. With regard to this discourse on school autonomy, the message is that headteachers have the “freedom” to manage their school in ways they deem appropriate. This includes appointing and contracting teachers, liaising with families and hiring external services. School institutions have the need to defend and bet on quality public education [22]. However, at the same time, they are held responsible for the decisions that they have carried out in a supposedly “autonomous” way. The subjects learn to govern and manage themselves without needing a strong external government to control them. Headteachers and teachers control themselves by following the norms of NPM such as effectiveness, efficiency and competence [18].

From within this context, education governance is perceived as a technique and technology of government which impacts the daily practices and management of schools. In this way, dynamics, functions, responsibilities, priorities and practices are redefined in terms of choice, competence, provision and “success”, which are all linked to performance indicators and the standardisation of results [17].

Oscillating between Neoliberalism and Neo-Conservatism in Education: The Case of the Spanish School Management Model

Public educational policies in Spain, mainly implemented by the conservative party (Partido Popular, known by its acronym (PP)), together with a historical-cultural legacy, which has its roots in the dictatorship of General Franco, highlight the idiosyncratic and distinct aspects of the Spanish state education system. This differentiates it from other countries in the West. In Spain, it is differentiated between neoliberal and neo-conservative principles. They cannot be understood as two sides of the same coin.

From this perspective, Spanish educational conservatism, which has a denominational base, rejects everything related to a common education, expressing an outright rejection of the educational practices carried out in comprehensive and inclusive schools [23].

The situation has worsened with the enactment of [24]. This law blocked attempts made by previous laws, such as [25,26], to democratise school governance and state-funded schools [15]. The language in [24] consolidated the neoconservative model in Spain in those years.

On the one hand, by imitating the rules of the market, neoliberalism highlights the free choice of schools and autonomy. On the other hand, neo-conservatism prioritises external regulation, exhaustive control and accountability together with other monitoring and surveillance mechanisms. All these are highly regulated and standardised in Spain.

At the same time, the contradictions existing between neoliberal and conservative approaches in Spain are further highlighted by the model of leadership and management of teaching centres (name deleted to maintain the integrity of the review process, 2016). With the introduction of [24], school management has moved close to the accepted model of business management, at least theoretically. The management of resources (including teaching resources) is perceived as being part of a quasi-educational market in which results and assessment (accountability) are of equal importance. It focuses on the “prestige” and the “image” of the centre, taking into account the demands of families (name deleted to maintain the integrity of the review process, 2016). In this sense, ref. [24] downplays collegiate participatory aspects while reinforcing those which are hierarchical and administrative. The macropolitical strategies that affect the micropolitics of educational centres have been analysed [27]. A commission, formed for the most part by representatives of the administration, is now in charge of appointing headteachers. In terms of appointing and naming these school headteachers, political interference by a conservative administration (the Popular Party) is obvious [14]. With this legislative change, the administration has the power to articulate commissions based on criteria relating to interests of ideology and patronage. The functions of the educational administration are specified in the LOMLOE [28].

All this makes the Spanish context a special case in which there exists strict control of educational centres by external agents (name deleted to maintain the integrity of the review process, 2017). This limits or even prevents a school from being autonomous. Neoliberal theoretical assumptions combine neo-conservative principles with the idea of controlling, allocating responsibilities, auditing practices and promoting an “entrepreneurial” ideology in educational management.

2. Materials and Methods

This study is framed within the interpretive paradigm [29]. The research design is based on a qualitative approach through semi-structured interviews [30]. Drawing on the testimonial sources of the data, it was considered appropriate to apply a qualitative research methodology [31]. The value of “the word”, as the core of a narrative-empirical construct, lies in its “meanings”. In other words, it lies in those experiences which have immediate certainty rather than being verifiable through traditional scientific methods [32]. The intention was to capture the subjectivities of human reality by means of a rigorous and systematic analysis of the verbal labelling. This method defends the re-elaboration carried out by the researcher, as it not only records the testimonies of headteachers but also attempts to “interpret” the experiences and perceptions within a social context [3]. Thus, the aim of this paper is to interpret and understand the patterns of social relationships (constructions and interactions), contextualizing the object under study [33].

The following issues were decisive in the adoption of a set of methodological decisions which were made prior to the field work:

- (1)

- Consideration of the weight of the discourse as a source of information;

- (2)

- Consideration of the chronological and historical perspective of the subjects’ perceptions and opinions;

- (3)

- Application of content analysis as a technique of the methodological process [34];

- (4)

- Application of the grounded theory as the basis for the construction of an emerging knowledge [32].

Thus, using content analysis as a basis for the reduction and structuring of information is corroborated [31]. From within this context, the study design highlighted the following methodological objectives:

- (1)

- To gather, analyse and organise the information emerging from the testimonies collected in the field work (level 1: content analysis);

- (2)

- To objectify beliefs, perceptions, valuations and unobservable elements of behaviour (level 2: content analysis);

- (3)

- To deepen the understanding of meaning of the subjects’ (inter)actions (level 3: content analysis (grounded theory));

- (4)

- To understand the emerging subjectivities arising from the investigation of the implications in Spain of the privatisation processes affecting education and school management (level 4: grounded theory).

The content analysis was, in the main section, translated into an inferential inductive approach using verbal, symbolic and communicative data (qualitative data). Being almost 100% present in the process of categorisation of information, this allowed us, during the comprehensive and interpretive phase, to establish a continuum with the successive deepening of the grounded theory [3]. On the one hand, the qualitative component of the study is highlighted, and an attempt is made to explain the social phenomenon (i.e., what is happening and why). On the other hand, there is the contribution of the grounded theory. This presents a set of arguments in order to explain the phenomenon under investigation. Using this process, and through the induction and comparison of the data emerging from the analysis, the concepts and relationships produced were examined. As a result, a type of “meaning” was generated, a meaning that “emerged” and made sense of the information [32].

2.1. Criteria for the Selection and Distribution of Key Informants

Taking into account the approach of this study, it was considered relevant to select a sample of 15 headteachers, chosen according to a specific profile. In this way, the sampling is labelled “intentional, homogenous, and restricted” [35]. This is because the aim was to reach specific groups starting from similar characteristics. This increases the degree of homogeneity within the sample. Thus, an attempt was made to obtain a high degree of representativeness of the population by means of a set of precise criteria, which defined the informants as follows:

- (1)

- Experience in the field of school management, which ensures a minimum number of experiences and practices in school leadership. Therefore, it was considered relevant for the subject to have held the post of headteacher for a minimum of 4 years (one term).

- (2)

- A demonstration of intention and presence in the processes of improving the educational results of the school by signing up for and participating in quality improvement programmes promoted by the educational administration.

- (3)

- Professional experience in terms of innovation.

The profiles of the subjects helped define the groups of secondary schools. In this regard, a broad and ecological perspective of the school context was adopted in order to gain an understanding of the situational characteristics of the interviewees during the period in which they were acting as headteachers. More specifically, it was decided that 15 Andalusian state high schools should be selected based on the following criteria:

- (1)

- Geographical location: The distribution of the student population in the schools was carefully examined (in Spain, this relates to home-school proximity). Consequently, the direct influence of the socio-educational context of the school emerged. This facilitated the selection of schools. Five schools were in the city centre, five were in neighbourhoods surrounding the city centre, and a further five were located in suburban areas and regions.

- (2)

- Socioeconomic and cultural index (SECI) of the schools (Education Council of the Junta de Andalucía of the Andalusian Agency of Educational Assessment): the SECI is pro-formed from the family context questionnaires, which includes variables such as resources in the home, educational level and parents’ occupation. Thus, it included five schools with high SECIs, five with medium SECIs and five with low SECIs.

- (3)

- The educational provision: this included school plans and syllabuses integrated into the educational project of the school. The inclusion of diversity programmes, initiatives for educational support, compensation and initial professional qualification programmes is evident in those contexts with greater socio-educational challenges. They are different, in this respect, from those which offer programmes focussed on the achievement of positive academic results.

Finally, the sample of schools was consolidated under the following nomenclature and codification:

Schools 1–5 (S1–S5): city centre, high SECI (0.9098–0.1806): innovation programmes, academic development and, to a lesser extent, attention to diversity programmes.

Schools 6–10 (S6–S10): macro city centre, medium SECI (0.0142 to −0.262): distribution between innovation-academic development programmes and attention to diversity programmes.

Schools 11–15 (C11–C15): peripheral and regional areas, low SECI (−0.374 to −1.536): mainly attention to diversity programmes and advanced professional training.

2.2. Data Collection Techniques

For the methodological design, an in-depth biographical interview outline was established in order to examine the practice of leadership in school management. Likewise, a series of questions was devised and integrated into the interviews. The questions focused on (1) school management, (2) incentive systems, (3) accountability, (4) efficiency, quality and performance, (5) control and (6) the role of the teaching staff.

These themes sought to encompass the reality and daily practice of the headteachers interviewed. In general, the interviews were designed to describe and highlight the experiences, perceptions and valuations of each of the subjects interviewed. In particular, a structure, based on a temporal diachronic axis (personal-professional career) and a synchronic axis (action and exercise of headteaching context), was proposed. From a narrative approach, the aim was to show how headteachers give meaning to their experiences, learning and actions [33]. In line with [3], the potential of this approach lies in going beyond the personal and idiosyncratic, reconstructing history while identifying problems and articulating singular narratives and testimonies within their general contextual framework.

2.3. Analytic Procedure of the Data

Following the field work, the next step in the project was to reduce and categorise the data through the implementation of content analysis.

In the first phase, it was important to establish a coding nomenclature, as well as a transcription procedure which would respect the channel and sources of information [30]. Once the analysis process had started, the constant dialectic exchange between the theoretical base and the data collected enabled it to progressively identify the registration units (RUs) in the text.

The second phase was determined by the “1st dumping” of RUs. Extracted from the sources of information, the RUs were organised into a series of pre-categories based on similarities, associations and representations supported by the study of the topics which were under investigation. At this stage, the RUs changed their name to units of analysis (UAs) or indicators (Is).

Given the low level of specification with regard to the emerging pre-categories, the third phase was carried out in order to expand the level of the structuring of the pre-categories. Thus, a “2nd dumping” was applied to the UA-I, which ended with a reorganisation of the emerging categories.

The fourth and final phase was characterised by assigning a categorical frequency index (CFI) to each category. The CFI was defined by the count of the indicators (Is). From an interpretive perspective, the CFI did not have a statistical nature. It was more of an approximation, as it represented the “weight” of the information contained in the emerging categories.

2.4. The Emerging Categories and the Criteria for Selecting Testimonies

The testimonies presented in this study are the result of the process of reduction-categorisation of the data (content analysis). Based on the work in [29], the intention was to combine the perspectives of the native (emic) and the researcher (etic). In practice, the narratives of the informants and the analysis of the researcher blend in a process similar to the joint construction of a shared story. This had the objective of understanding the social reality and the meanings found in the narrations. In this regard, the identification and selection of content (testimonies) is justified, as is evident from the confluence of three fundamental criteria:

- (1)

- The CFI of each emerging category (degree of significance of the narrative weight);

- (2)

- The criteria of the information analysis supported by the theoretical foundation of the study (etic, top-down);

- (3)

- The knowledge emerging from the sources of information (emic, bottom-up).

From the confluence of these criteria, the emerging categories were consolidated, as well as the key aspects in the selection of the most pertinent testimonies. The following classification represents, in general terms, the results of the entire process: representative of the administration, school planning and organisation, administrative function, autonomy and pedagogical authority, professionalisation and control mechanisms and accountability.

3. Results

Implications of the Privatisation Processes in Education within State School Management in Spain

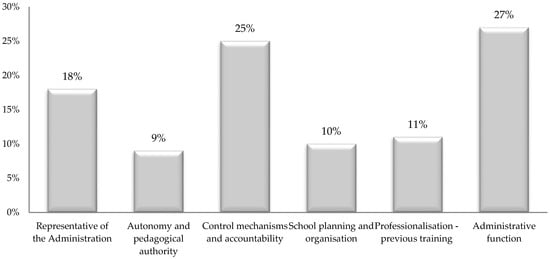

The results of this study present a descriptive view of the distribution of information found in the emerging categories. With regard to this, we present the trends evident in the weight of the information reduced to the CFI (in percentages), shown in Figure 1. In the same way, the most referenced categories for total quotations are administrative function (27% CFI) and control mechanisms and accountability (25% CFI). At an intermediate level, there is representative of the administration (18% CFI) and finally, with a low frequency although no less important, professionalisation (11% CFI), school planning and organisation (10% CFI) and autonomy and pedagogical authority (9% CFI). Among other issues, the importance and interest in the role of educational administration in these processes can be seen. This was, without a doubt, the most referenced factor.

Figure 1.

Distribution of CFIs (in percentages) by emerging categories. Source: the authors.

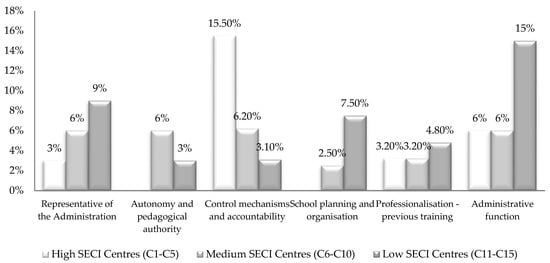

As can be seen in Figure 2, it is possible to observe the crossing of the dimensions in which the impact of neoliberalisation processes is expressed in school management with the type of centre. There are certain “regularities” worth taking into account. In light of this, it is probably not fortuitous that (1) the headteachers from the low-SECI centres referred the most to the administrative function category (15% CFI), and (2) those who managed the high-SECI centres put more emphasis on control mechanisms and accountability (15.5% CFI). In the same vein, this may be a response to how the demands of the administration are mediated by the situational characteristics (and educational results) of the centres. Hence, the headteachers of the high-SECI centres made no mention of their autonomy and pedagogical authority nor their ability to plan and organise the school. In other words, they appear to be firmly focused on responding to the demands of the educational administration. On the other hand, it is not by chance that the headteachers of the low-SECI centres appear repeatedly in the categories representative of the administration (9% CFI), school planning and organisation (7.5% CFI) and, at the same time, administrative function (15.5% CFI). It seems that the weight of the bureaucratisation of managerial duties is more critical in these contexts. Finally, it can be seen that the category which refers to the professionalisation processes for the managerial position is an issue which, to a greater or lesser extent, concerned all three types of centres.

Figure 2.

Distribution of CFIs (in percentages) by emerging categories, depending of the type of centre (SECI). Source: the authors.

Grounded Theory: Headteachers’ Perceptions and Evaluations

This section combines the interpretive approach with the narrative dimension of the study [26]. In this sense, it presents the testimonies of the interviewees and reveals the different ways in which headteachers relate to their practice. The way in which spaces have opened up for questioning and dealing with problematic issues can be observed. Professional ethics could be the key factor in supporting headteachers when investigating the possibilities of transgression and resistance, in addition to exploring new ways of working [36]. Criticisms, intolerance, discomfort and wishes are expressed in this way. As a result, ideas about a change of model are expressed. This in turn leads to a conversion of oneself, which moves away from the established reality [36].

The narrative thread of the grounded theory opens with the category (headteacher as) representative of the administration. During the 1980s, school headteaching in Spain tried to break with a centralist conception in schools. This was a particularly heroic attitude at that time. The aim was to achieve a participatory and democratic model which perceived the headteacher as a representative of the school community and, at the same time, as an agent responsible for coordinating the centre’s activity [15]. With the advance of neoliberal policies in the 1990s (and beyond), the parameters of a “new governance” started to come under observation. This included the concept of the headteacher as an agent of the educational administration (i.e., a kind of supervisor required to respond to the guidelines of the high authority) [37]. Thus, the senior management team of a school has been reformed, resulting in the adoption of a pyramidal structure. This structure leads to an intermediate situation, which results in a “field of tension” between the interests of their fellow teachers and the demands of the educational administration (name deleted to maintain the integrity of the review process, 2016). Although this category has been referenced more in the contexts of low SECI, it is an issue which relates to all the three types of centres:

...I’m a representative of the public administration which is devoted to solving problems with families, problems of coexistence, conflicts [...] I have no time to reflect on pedagogical issues (C9) (The nomenclature of educational centres responds to the following coding: C1–C5 (High SECI); C6–C10 (Medium SECI); C11–C15 (Low SECI)). […] I have to take sides with the administration or with the teaching staff, it is very complicated! [...] (C2) [...] and sometimes you feel very lonely [...] because in the face of any problem, at the end of the day, you are alone [...] I have called the administration looking for advice on certain things and... no [...] sometimes I even end up quarrelling on the phone, and I’ve felt very lonely... now... if something happens, you are the only responsible to the administration (C15) [...] the delegate of the administration should ask me for less papers, I’m not her secretary! (C5) [...] we are in no man’s land, mediating between the administration and the teaching staff [...] and, before the teachers, you are defending the indefensible of the administration; things that you do not believe much either [...]. It seems that the administration sent me to the educational centre to comply with and enforce the law [...]. I am caught in the middle!(C13)

This radiography shows what was described in [38] as “steering at a distance” and referred to in [12] as “government at a distance”, which from a managerialist perspective relegates school headteaching to a secondary role in accordance with the guidelines set by the educational administration. In line with this, the testimonies of the headteachers allowed us to observe how neoliberal processes affect both schools and individuals. We refer here to “rule”. This is the behaviour of individuals through regulation and self-regulation techniques [8]. From the “outside”, headteachers are held responsible for fulfilling those functions which are subordinated and subjugated to the demands of the higher levels of the administration (economic dimension). On the other hand, from the “inside”, headteachers feel “responsible” for acting in accordance with those demands [39]. This is what was called “performativity practices” in [38], or the way in which the behaviour of individuals and groups can be (self-)directed in an isolated and individual way. Within this framework, the state of “responsibility” (or irresponsibility) and feeling of “isolation”, as expressed by the interviewees, accounts for a performative technology, which atomises the subjects (dividing, identifying, etc.) while assessing their success or blaming them for their failures [40]. It is not surprising that the administrative function of school headteaching emerges with force in these processes. This is a form of techno-bureaucratic regulation which tries to (indirectly) control and assess, through the school headteachers, issues such as the school curriculum and teaching processes. The students’ educational results are, undoubtedly, affected by these factors [14]:

Here, the senior management team is responsible for more than 85% of the management and administrative work [...] this absorbs all of your time, even outside of school hours, weekends, evenings... (C6) [...] I have so much administrative work that I forget that I’m in school, in an educational institution; this often seems like an administrative office, and this is a shame (C14) [...] I understand that a person is necessary to coordinate, and I try hard for it; but there is a significant distance from there to not doing any of the pedagogical tasks [...] it is necessary to leave the management for the administrative people! (C15) [...] Let’s see... if the headteacher is going to take on a managerial role, I understand that the director of studies should help him, so as not to leave the more educational, pedagogical matters, etc. (C3) [...] Now, if we are in the situation in which both the secretary, the headteacher, etc. are teaching, the problem is that we cannot cover all the work, it is impossible! You do not get to meet the demands for all completion of all the tasks which the administration asks!(C3)

These statements indicate the impact of the ways of “being” in schools. As can clearly be seen, the interviewees felt isolated, absorbed by a tireless routine of writing reports and keeping records, tasks which dominate their daily practice. They have to respond to a feedback structure and performance indicators which fail to facilitate their pedagogical work and social relationships [11]. In this way, the subject is assessed solely in terms of productivity [8]. Personal values are eradicated, and results take priority over processes, numbers over experiences, procedures over ideas and productivity over creativity [39]. Moreover, the issues which arise have already emerged in other investigations within the Spanish context [41]. Under this topic, and in the case of schoolteachers in Castile and the Basque Country, it was evident that these processes increased the volume of administrative and bureaucratic activity. They have rarely presented didactic improvements or improvements which at least could have had an impact on classroom practice and the educational development of students. All this relates to the need for constant information about what takes place in educational centres on a daily basis. With regard to the category control mechanisms and accountability, one of the goals of the NPM is to control “school autonomy” [7], thereby “regulating from outside what is happening inside”. According to [42], “this is Taylorism applied to the school.” This is how it was expressed by the headteachers who were interviewed:

The administration controls us more and more... we have to fill in the documents through online portal, and the administration bombards you with additional documents to fill in and return in time [...] then, they assess us from there (C14) [...] for the senior management team, this thing of fulfilling what Séneca asks of you is all a matter [...] it is a totally stressful situation because they ask you for a lot of information, you have little time to upload it and, above all, from there they assess the whole school [...] and from there depends, to a large extent, the resources which they allocate to you (C13) [...] there is a lot of paper-work to give to the inspector, a lot of reports to introduce through Séneca, a lot of assessment, and that weighs heavily on my back; at times, I cannot do more [...] teachers pass by and say ‘take, here you have my things’, and they get out of that; that is the reason why I’m snowed under with paper-work and administrative tasks.(C10)

To the detriment of having a foundation or reason for headteaching practice (i.e., to find the true meaning of the headteacher’s task), the focus is firmly on the production of results and the optimisation of measurable achievements. This is in pursuit of “what works” [39]. Furthermore, this is the way in which knowledge circulates. It is what Foucault (1982) calls the relation to power within the framework of neoliberal processes. Furthermore, it is a relationship which produces subjects who are measurable and who can be categorised and dominated by an arbitrary authority which restricts their freedom. Consequently, it is not surprising that discouragement, stress and frustration are commonplace. This is what was identified in [36] as a “processes of confrontation.” However, these are not necessarily conscious conditions, which implies a resistance to practices and shows a distancing from what the subject does not want to become, thus defining his or her role and stance.

The headteachers of the high-SECI centres saw this from another perspective:

I understand that, in one way or another, all activity must be assessed in order to get a better performance [...] I do not think negatively about a certain amount of control by the administration relating to what happens in the centres, although I prefer self-control [...] the point is how the accountability is done, the design; in this way, we are not going anywhere (C1) [...] the administration sometimes works with rigour first and misuses its resources [...] and I understand that we have to be accountable because, from this perspective, the public sector can be losing more and more competitiveness, although it is not done in this way. There is so much paperwork, so much control and assessment of aspects which have nothing to do with the pedagogical issue.(C3)

These excerpts show the formula for managing the improvement in learning outcomes by the educational administration (close to the business field) rather than granting institutional autonomy. In addition, it increases the levels of pressure and stress experienced by the teaching staff and the headteacher [16]. Therefore, these headteachers perceive their performance (and themselves) as part of a process of external assessment and control, which includes accountability and competitiveness. Furthermore, they accept that they are developing their daily practices through language and decisions which are promulgated by neoliberalism and its technologies [43]. According to Dean [44], it is possible to see how the subject is “governed by others” while, at the same time, “governing him/herself” and “understands him/herself” in direct agreement with those forms which govern him or her.

From this perspective, the category autonomy and pedagogical authority (of the headteacher) presents evidence which relates in particular to the development and articulation of the concept of resistance [39]. This is part of what was called “taking care of oneself” (i.e., “to be concerned with oneself” or “being true to oneself”) in [45]. This is an important rule for social and personal behaviour in the “art of life”, and it implies notions relating to the configuration of the identity of the subjects. Within this framework of identity and construction of subjectivities, the concept of resistance emerges from the tensions existing between the processes of domination of the subject and his or her freedom [38]. Thus, resistance is focused on the possibility of transgressing the dominant discourse and the promotion of neoliberalism and its technologies. Its main objective is to attack its techniques, its forms of power and the relationships which emanate from it [38]. From this standpoint, resistance takes the form of an ethical reflection on our personal history and ourselves [39]. Resisting one’s own practices through criticism, confronting discontent, questioning the “common sense” of things and exposing power relations are all forms of resistance and “taking care of oneself” in the search for creating spaces of freedom which allow us to think differently [46]. According to the interviewees:

The inspector is important, but maybe I should have a little more power here [...] I dedicate myself to everything except the pedagogical; there are a thousand things which take up my time (C14) [...] we do not have pedagogical authority and, since they are talking about the autonomy of the centres, all of this is absolutely ridiculous (C11) [...] we do not have authority, real authority... we have to call the Delegation for everything, asking for a permit, an insurance, the inventoried material... [...] well, we cannot work in this way, we are accountants for the administration! (C13) [...] here, the one that should pedagogically assess the teaching staff is the headteacher, not the administration... in fact, the administration asked me for an assessment through a Quality Improvement Plan. Can you imagine what a massive responsibility they gave me, in not having authority by myself... I had many problems with the teaching staff... it is very hard.(C7)

Through their discourse, these headteachers “do resistance” by highlighting and making an issue of their own practice and deconstructing and examining their situation in a critical and reflective way [47]. They are able to analyse and identify the structural limitations of the system (including autonomy, authority, power and assessment) as well as recognise themselves as subjects of audit and management (administrative) practices. This is what was perceived in [38] as the development of an “aesthetics of the self”, a technology in which the individual recognises herself or himself by “who she or he is” and by “who she or he might become”. What is not taken into account, despite the headteachers’ aspirations, is their re-articulation as pedagogical subjects, or their active role in self-definition as a “headteacher with pedagogical capacity.” As a result, this leads to the possibility of this experience changing in the future [39].

This foundation is extendable to the category of school planning and organisation. Being caught between the demands of the administration and the resistance of the teaching staff, the headteacher is “besieged” or “captive” (name deleted to maintain the integrity of the review process, 2016), with no room for action other than in administrative tasks and in activities related to school planning and organisation, which take place in the “periphery of the classroom”. They do not have the power to intervene (or advise) on basic pedagogical issues. According to the subjects:

My power in the centre is limited [...] I have no choice but to take care of the annual and monthly schedules [...] I try to generate strategies, meetings, projects, but I cannot move forward from the task of the merely coordinating (C6) [...] I am the one who plans and organises the centre, in order to maintain an adequate working climate [...] I dedicate myself to assistance, conflicts, presenting and preparing documents for the Ministry [...] there is no time to do anything else, I do not even have time to go into the classroom, although the inspector asks me to do so. That is unthinkable given the reluctance of teachers to hear about how they should do their work in the classroom (C8) [...] Just for the planning of the extracurricular activities I have worked for months [...] I have had to change everything three to five times [...] the management team cannot assume the organisation of all activities! We cannot cope! (C4) [...] While the administration is focused on school results, I’m thinking about creating a coexistence climate [...] that is paramount; if not, nothing is achieved [...] in addition to all the bureaucratic work which I have to do, I have had to reorganise the whole centre from scratch [...] and it is very difficult when, on the one hand, they ask for results and supervise the teaching staff and, on the other, they act defensively [...]. I am constantly caught between two fronts and am very restricted.(C3)

From these testimonies, the discomfort and rejection (resistance) felt by the headteachers in relation to their situation is clearly revealed. They are aware of how various power relations limit them in an immediate sense both spatially and temporally [39]. At this level, they are able, in a critical way, to see how instances of power exert a negative influence on their professional status and development [38]. On the one hand, those at the higher levels of administration demand a way of headteaching which is in line with the logic of competition and focused on the headteacher as an administrator who is assessed but who is also the one who assesses others. This is the homo aeconomicus or “entrepreneur of himself” [43]. On the other hand, the headteachers exhibit a “defensive” attitude, which leads them to question their situation even more. Such a field of tension enables them to highlight the power relations which interweave and merge with their daily tasks. In addition, their projection and self-definition as “managers capable of developing their pedagogical dimension” is revealed [14]. In short, this vision connects with the management approach in [7], which is referred to above. From this perspective, autonomy is seen from the perspective of NPM logic, in which the school headteacher performs the functions of a business manager.

The category professionalisation: previous training (of the headteachers) closes the narrative construct. Here, the situation is complex. The dilemma relating to what sort of training should be assigned to the profile of each headteacher comes under discussion. Within this context, headteachers [48] demand professionalisation which is less centred on the administrative management of the educational centres. On the other hand, as is argued in [49], the skills of the “new manager” involve a distancing from “educational problems” as she or he disregards the practices of classroom teaching. The aim is to resolve the ambivalence between increasing the competence of teachers in management tasks (technical competences) and establishing school headteaching as a function which is distinct from classroom teaching with the development of a (participatory and democratic) pedagogical dimension. While this dilemma is still under debate, the reality facing headteachers in these educational centres is worth taking into account:

(Regarding lack of training) I know many who have assumed the role of headteaching without training [...] I took over the post with a little morning course, one Wednesday a month. But look, we are talking about a person leading a centre. Let’s be serious: if here there had to be someone, please, let it be someone who is prepared, someone who knows (C7) [...] I have barely had any training for this position, and I did not feel qualified for at least the first year (C2) [...] What is unforgivable is our lack of training [...] we do not have a lot of professional training, and then it is a job which is done with a lot of good intentions, but with a lack of competence. (C14) [Type of training] I don’t find any direction [...] I lack management skills [...] we lack training (C3) [...] the teacher training which we received from the public examinations was not enough (C1) [...] the pedagogical direction is very complex and even more so if you do not have specific training (C8) [...] when you start your job you are unprepared [...] when you arrive, you are overwhelmed by the volume of administrative duties. This is due to a lack of specific training (C9) [...] Headteaching should be a professional career, different from the teaching staff, where one learns to manage a centre.(C10)

From these excerpts, the complexity involved in the construction of a professional identity for headteachers in Spain can be seen, in addition to its implications in terms of professionalisation. From an identity perspective [2], the headteachers’ struggle and their uncertainties are defined by their difficulty in finding points of convergence between the projection of the “identity for oneself” (a “pedagogical leader” in the school with specific training related to that) and their “assigned identity”, which is designated by the higher levels of authority. In other words, they are productive subjects weighed down by the logic of competition. This issue permeates the professional duties and experience of headteaching. Furthermore, it lies in finding an ontological basis for a headteacher’s professional practice. In this sense, the interviewees are aware of themselves in addition to the importance of their performance. The value they give to their (specific) training accounts for this. However, not all of them relate their duties and professionalisation to the development of pedagogical headteaching. Given this, it appears that they have integrated the headteaching model with that of an administrator [7] (i.e., the person who produces measurable and “improved” results and prioritises “what works”) [39].

4. Discussion

This paper offers an analysis of neoliberalisation processes from the perspective of NPM. Additionally, it explores the principles which govern educational “good governance.” Neoliberalism has been analysed and described as a complex phenomenon which transcends a mere interest in global capitalism with its constant mantra of accumulating profit [5]. The NPM redefines world governance and, in so doing, produces novel relationships between different social actors, such as the state and capital [6]. It has been seen how individuals construct a worldview based on competition [43] and from the context of neoliberal rationality. In the world of education, the NPM focuses on strategies which aim to discipline both teachers and management teams, using accountability mechanisms and assessment [8]. Thus, within the education system, NPM is introducing modes of bureaucratic governance which possess the values and principles of the private sector [9]. As a result, they are transforming the role of the headteacher into that of a representative of the educational administration with a predominantly managerial function, rather than a school headteacher with pedagogical skills and responsibilities [7].

The focus of this paper was on the construction of a neoliberal subjectivity, such as how the logic of “good governmentality” constructs us [10] and “makes us” see the reality of current educational practises and the functions of school headteaching, through entrepreneurial lenses. In other words, it perceives headteachers as “entrepreneurs of themselves”. It is hoped that it the fact that NPM guides the principles of the “good governance” as a form of governance which assesses the work of school headteachers in terms of profitability and performance control has been clarified. In countries like Chile, Spain, Norway and the United Kingdom, educational reforms centred on NPM perceive governance in terms of the school’s autonomy and freedom of choice (e.g., when a family is selecting an educational centre or school), in addition to professional accountability and management based on results [7].

In the Spanish context, NPM seeks to discipline the school headteacher and control the autonomy of the school [14]. A reflexive view of the educational policy of recent decades points to the tendency of public administrations to seek a headteaching model which is increasingly “professionalised” with a marked managerial character. In Spain, a clear change of orientation can be seen, not only in the way headteachers are appointed but also in the professional profile of headteachers, in addition to the functions which they are expected to perform. Since the end of the General Franco’s dictatorship with [50] and later with the laws during the democratic periods of [51] and [26], participation in educational centres has gradually been encouraged. Both teachers and families took part in the election of the headteacher, as well as in the government and management of the centre through school boards. However, with [52] and [24], both promoted by the ultra-conservative party (PP), this participation was severely restricted, thus considerably diminishing school democracy. According to [15], these laws “end up giving the coup de grace to participation, opting for a management model which responds to neoliberal and neoconservative references.”

In this way, [52] modified substantial aspects of previous laws with the intention of redefining the functions of the headteacher and her or his election. It incorporates, as a key requirement, new competences for the headteacher so he or she has more power, at least on the theoretical and normative levels. However, at the same time, this limits the flexibility and options of the school board. The headteacher’s role is “professionalised” and assumes more power to manage and control the centre. Thus, the educational administration is committed to a more pyramidal model which lands on NPM’s own accountability. The neoliberal and neoconservative vision was deepened by [24], facilitating conditions which favour the market managerial model [15].

In summary, the changes in educational policies can be seen, especially under [24], as moving towards a new profile of headteachers, namely one which is more managerialist. The different issues which have been studied in this research, fundamentally marked by contextual factors (for example, more impoverished and vulnerable environments), demonstrate how neoliberalism is normalising the tendency to redefine the role of the headteacher as a manager. Moreover, it shows how the headteacher is someone who is under the control of the administration and required to follow its guidelines. Ultimately, this paper refers to a “professional” who is responsible for “disciplining” teachers in addition to being required to produce positive academic results. As a result, headteachers are caught between two realities. On the one hand, they are subject to the control and accountability required by the administration. On the other hand, they face resistance and challenges from their teaching staff on a daily basis. This is what is meant today by “educational business”.

This is particularly relevant if we take into account the fact that in Andalusia, the number of candidates applying for the position of headteacher has declined dramatically. The Andalusian Regional Government’s opposition to [24] and its rejection of the measures for its adaptation have forced them to appoint headteachers (or extend the duration of their tenure) on a provisional basis. This action is being taken by this administration regardless of the standard procedures. Paradoxically, this means applying [24] anyway because headteachers are directly appointed to their posts by the regional administration rather than by the educational community [14].

5. Conclusions

Throughout this study, the goal was to maintain consistency with the introductory proposals. In this way, the link to a critical and constructivist approach of reality has called for careful consideration, taking into account the impact of context (social, historical, cultural, etc.) as a determining element in the configuration of those regularities (perceptions, valuations and beliefs). This was then exposed to a (methodological) procedure of analysis and interpretation.

Overall, this research has managed to gather data relating to the advance of neoliberalisation processes in state education in Andalusia (extendable to the rest of Spain). It focuses in particular on how school headteaching in state secondary schools is influenced by neoliberal processes.

In the theoretical framework, it was necessary to establish an approach capable of establishing a foundation for the concepts, phenomena and facts which are evident in the results of this study. Thus, reference is made to a state of affairs which vertically covers the neoliberal phenomenon, its structural implications (systemic governance from the outside) and action dynamics (personal governance from within).

The results of this study highlight the particularities of the Spanish context. Together with the emerging categories, the dimensions of the impact of neoliberal advances are described. A transversal view implies that educational administration is a determining factor. The interest in its interference and its reiteration are undoubtedly mediated by socio-economic and cultural characteristics (SECIs) in addition to the educational results of the schools investigated. When examining these variables (and as the analysis moves closer to disadvantaged social contexts), there is evidence of a greater presence and resistance from headteachers in terms of their relationship with the administrative hierarchy. Whether due to the lack of a “context view” on the part of the administration towards the centres or the problems linked to the “situational reality”, it is evident that in these contexts, the demands of the administration are unwelcome. These issues are reflected in the narrative construct found in the categories administrative function (bureaucratisation of functions), representative of the administration and school planning and organisation.

Following this, the narrative construct relates to the regularities of the emerging categories which deserve to be taken into account. There is little doubt that one of the effects of “good governance” has influenced the change in identity of the headteachers (name deleted to maintain the integrity of the review process, 2016). The perception of “themselves” as representatives of the administration accounts for this. It is a (socio-professional and intermediate) positioning which exists between the demands of the administration and the interests of teachers and which transcends the structural aspects of the management model, such as the system of choice and strategies for promotion. In this context, the role of an agent-manager, who devotes a huge amount of time to administrative tasks, is reconfigured. These terms refer to a type of techno-bureaucratic form of regulation which shows, as evidence, a concern for the superior levels of control (and accountability). Furthermore, it belies the existence of a “real autonomy” within educational centres with regard to pedagogical, organisational and other aspects. Added to this, and as an aggravating factor, is the lack of professionalisation (training) of school headteachers. This is a key issue, particularly if we consider that today, the demands of the administration and teachers on the management functions of schools primarily require management and conflict resolution skills.

In short, there exists a binding analysis of these categories which exposes the many processes of neoliberal domination and governance currently existing within the Spanish educational system. According to Meens [8], it relates to a form of governance which holds headteachers accountable for the success of the school (top-down, “governed by others”) but, at the same time, makes them feel responsible for the results of their work (bottom-up, “governing of oneself”). In this way, regulation and self-regulation techniques create a framework for the power relations which control the “school’s autonomy”, as well as other aspects. In this double game, NPM’s logic of competition prioritises measurable actions in order to standardise and produce results. Consequently, it sees the headteacher as a business manager (with administrative functions and as an instrument for assessment within the school); that is, he or she the one who is assessed but also the one who assesses others, in addition to assessing those processes involved in the management of the school. This takes place within a culture of productivity which destroys and underestimates headteachers in their personal dimension. There are, of course, headteachers who are sympathetic to this approach and to “the forms which govern them” and who are willing to (re)produce the neoliberal regime of truth (and its technologies). Others, as can be observed, are capable of creating spaces of resistance based on an ethical reflection of their experiences. In this regard, they recognise themselves not only in terms of “who they are” but also in terms of “who they might become” (a “headteacher with pedagogical capacity”). This is their “space of freedom and transgression”. Where appropriate, those expressions of disappointment, stress, frustration and so on are configured as “confrontation processes” which reveal criticism, discomfort and questioning or, in short, their resistance to “what they do not want to become”. This is the way in which they define their role and stance. From a Foucauldian perspective, these headteachers expose and highlight, in a critical way, the impact of power relations on their professional role [33]. As a result, their autonomy, authority, power, assessment, collegiality, etc. are at stake. This results from a stance which projects and defines them.

In short, successive educational reforms have been unsuccessful in influencing the worrying deficit in pedagogical headteaching in Spanish schools. Given that this is the current situation, much-needed professionalisation has nothing to do with an administrative-bureaucratic solution. School headteaching must have the capacity to offer a better form of education to students on a daily basis. In addition, a critical point relates to what the headteacher is doing or what he or she can do in order to improve the work of staff teachers in their classrooms and, consequently, enhance learning among their students. According to Fullan [53], this would mean “repositioning the role of the headteacher as a general pedagogical leader in a way that maximises the learning of all teachers and, in turn, of all students”. This would represent the culmination of those forms of resistance to neoliberal logic which, to a certain extent, has been expressed in this work.

In conclusion, questions still arise about the capacity to develop headteaching, teaching beliefs and those practices which transcend the neoliberal “regimes of truth”. However, as discussed, there exists the possibility of transgression and resistance and, therefore, the potential to assume an active role in self-definition. In other words, we believe in a critical and reflective subject who can instigate challenge and change in the face of the many problems which beset headteachers in Spain.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.R.-R. and F.M.R.-M.; methodology, D.G.-R.; software, M.R.-R.; validation, F.J.J.-R., M.R.-R. and F.M.R.-M.; formal analysis, D.G.-R.; investigation, M.R.-R.; resources, F.M.R.-M.; data curation, F.J.J.-R.; writing—original draft preparation, F.M.R.-M.; writing—review and editing, D.G.-R.; visualization, M.R.-R.; supervision, D.G.-R.; project administration, M.R.-R.; funding acquisition, M.R.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness. General Directorate of Scientific and Technical Research, R&D Project: Identity of school management: leadership, training and professionalization (Code: EDU2016-78191-P).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

This study is derived from the R&D Project: Identity of school management: leadership, training and professionalization (Code: EDU2016-78191-P).

Acknowledgments

Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness. General Directorate of Scientific and Technical Research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Young, M.; Crow, G. Handbook of Research on the Education of School Leaders; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Day, C.; Gu, Q. Educadores Resilientes, Escuelas Resilientes (Resilient Teachers, Resilient Schools); Narcea: Madrid, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sugrue, C. Unmasking School Leadership: A Longitudinal Life History of School Leaders; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, A.E.C. Ignasi Brunet Icart y Rafael Böcker Zavaro, 2013. “Capitalismo global: Aspectos sociológicos”. Madrid, Grupo 5. Cuad. Relac. Labor. 2018, 36, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brown, W. Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution; ZoneBooks: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, M.; Raymond, D. Power in International Politics. Int. Organ. 2005, 59, 39–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Verger, A.; Curran, M. New Public Management as a Global Education Policy: Its Adoption and Re-contextualization in a Southern European Setting. Crit. Stud. Educ. 2014, 55, 253–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meens, D. Democratic education versus smith an efficiency: Prospects for a Dewey an ideal in the ‘neoliberal age’. Educ. Theory 2016, 66, 211–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leys, C. Market-Driven Politics; Verso: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, S. The Neo-liberal Revolution. Cult. Stud. 2011, 25, 705–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, S. Neoliberal governance and pathological democracy. In La Gobernanza Escolar Democrática; Collet, J., Tort, A., Eds.; Morata: Madrid, Spain, 2016; pp. 23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Piattoeva, N. Elastic numbers: National examinations data as a technology of government. J. Educ. Policy 2015, 30, 316–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, N. Powers of Freedom: Reframing Political Thought; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bolívar, A. Meaning of a Spanish Framework for Good Headteaching in the current problems of school headteaching. Organ. Gestión Educ. 2018, 26, 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Bernal, J. Educational Centres Organisation: LOMCE and Neoliberal Policies; Mira: Zaragoza, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins, A. School governance and rationality of the neoliberal policy: What has to do democracy with that? In La Gobernanza Escolar Democrática; Collet, J., Tort, A., Eds.; Morata: Madrid, Spain, 2016; pp. 84–100. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins, A.; Olmedo, A. Education Governance and Social Theory: Interdisciplinary Approaches to Research; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Collet, J.; Tort, A. Hacia la Construcción Colectiva, y Desde la Raíz, de Una Nueva Gobernanza Escolar. In La Gobernanza Escolar Democrática; Collet, J., Tort, A., Eds.; Morata: Madrid, Spain, 2016; pp. 127–137. [Google Scholar]

- Lubienski, C. Re-making the middle: Dis-intermediation in international context. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2014, 42, 423–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Puelles, M. La influencia de la Nueva Derecha inglesa en la política educativa española (1996–2004). Hist. Educ. 2005, 24, 229–253. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, J.; Ozga, J. Working Paper 4. Inspection as Governing. 2012. Available online: http://jozga.co.uk/GBI/tag/working-paper/ (accessed on 28 June 2018).

- Torres, J. Políticas Educativas y Construcción de Personalidades Neoliberales y Neocolonialistas; Morata: Madrid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Olmedo, A.; Santa Cruz, E. Middle class families and school choice: The instrumental order as a necessary but not sufficient condition. Profesorado 2008, 12, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ley Orgánica para la Mejora de la Calidad Educativa (LOMCE) (Ley Orgánica 8/2013, 9 de Diciembre), BOE, no. 295. 10 December 2013.

- Ley Orgánica Reguladora del Derecho a la Educación (LODE) (Ley Orgánica 8/1985, 3 de Julio), BOE, no. 159. 4 July 1985.

- Ley Orgánica de la Participación, la Evaluación y el Gobierno de los Centros Docentes (LOPEG) (Ley Orgánica 9/1995, 20 de Noviembre), BOE, no. 278. 21 November 1995.

- Viñao, A. El Modelo Neoconservador de Gobernanza Escolar: Principios Estrategias y Consecuencias en España. Más Allá de los Modelos Neoliberales y Neoconservador. In La Gobernanza Escolar Democrática; Collet, J., Tort, A., Eds.; Morata: Madrid, Spain, 2016; pp. 41–64. [Google Scholar]

- Ley Orgánica 3/2020, de 29 de Diciembre, por la que se Modifica la Ley Orgánica 2/2006, de 3 de mayo, de Educación (LOMLOE).

- Popkewitz, T. Paradigm and Ideology in Educational Research; Routledge: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bruner, J. Acts of Meaning: Beyond the Cognitive Revolution; Alianza: Madrid, Spain, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ávila, J. Por uma Analise de Conteudo Mais Fiavel. Rev. Port. Pedagog. 2013, 47, 7–29. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. Grounded theory: Objectivist and constructivist methods. In Contemporary Field Research; Emerson, R., Ed.; Little, Brown and Company: Boston, MA, USA, 2004; pp. 109–126. [Google Scholar]

- Goodson, I. Investigating the Teacher’s Life and Work; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wertz, F.J.; Charmaz, K.; McMullen, L.M. Five Ways of Doing Qualitative Analysis: Phenomenological Psychology, Grounded Theory, Discourse Analysis, Narrative Research, and Intuitive Inquiry; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Clairin, R.; Brion, P. Manual de Muestreo; La Muralla: Madrid, Spain, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gunter, H. Leaders and Leadership in Education; Chapman: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Merchán, F.J. The introduction in Spain of the educational policy based on the business management of the school: The case of Andalusia. Educ. Policy Anal. Arch. 2012, 20, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. The subject and power. In Michel Foucault: Beyond Structuralism and Hermeneutics; Dreyfus, H., Rabinow, P., Eds.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1982; pp. 208–226. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, S.; Olmedo, A. Care of the self, resistance and subjectivity under neoliberal governmentalities. Crit. Stud. Educ. 2013, 54, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, P.; Rose, N. Governing the Presente; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ayerbe, P.; Etxagüe, X.; Lukas, J.F. Assessment of centres in the Basque Country. Bordón 2007, 59, 5–29. [Google Scholar]

- Rezai, B.; Martino, W.; Rezai-Rashti, G. Testing regimes, accountabilities and education policy. J. Educ. Policy 2013, 28, 539–556. [Google Scholar]

- Ong, A. Neoliberalism as a mobile technology; Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2007, 32, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, M. Governmentality: Power and Rule in Modern Society; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]