1. Introduction

This study is framed within the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) set by the UN [

1]. Concretely, the 4th goal, Quality Education, pledges to ensure “inclusive and equitable quality education and promote life-long learning opportunities for all”. By 2030, this goal is set to guarantee equal access to higher education for all individuals, including the elimination of inequalities marked by gender, ethnicity, or other vulnerabilities. Specifically, this research contributes to addressing the objective of gaining equal access to higher studies for ethnic minority students.

Creating conditions to improve the educational attainment of the population constitutes a unique opportunity to promote social inclusion, reduce poverty and consolidate a more sustainable growth model [

2,

3,

4]. Consequently, this proposal seeks to provide an effective response to the educational exclusion suffered by one of the most vulnerable groups in Spain and Europe—the Roma community.

Despite the difficulties in collecting ethnic data in Spain, available surveys demonstrate the low educational level of the Roma population in Spain. A survey of Roma households conducted by the Centre for Sociological Research (CIS) concluded that 96.9% of panel participants had only completed primary education or less [

5]. Furthermore, a more recent study found that only 2% of the Roma population in Spain had completed higher education, without observing significant increases in the younger generations [

6].

Recently, the National Strategy for the Social Inclusion of the Roma Population in Spain, 2012–2020, [

7] has been working to create synergies with other policies and actions, such as the Framework for European Cooperation in Education and Training, 2020, or the Comprehensive Strategy against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia, and Other Related Forms of Intolerance [

8]. These initiatives underline education as the key to social inclusion and establish the need to increase the share of the Roma population that completes post-compulsory studies. Additionally, the need to improve the intercultural training of teachers is highlighted.

Strategic actions include measures that promote university access for the Roma population and scholarship programs [

7]. However, references to higher education remain scarce and vague. The need to increase post-compulsory graduation rates among the Roma population is recognised, but specific actions aimed at achieving this objective are not sufficiently developed.

With the aim of filling this gap, the present study focused on identifying the profiles of Roma students who are currently studying at Spanish universities, examining the barriers they face and formulating recommendations to support these students.

2. Literature Review

Despite the existence of an important research field addressing the situation of the Roma population in compulsory education, few studies have focused on higher education. However, the low share of Roma people graduating from university raises the need to develop studies to identify the profiles and needs of Roma university students in Spain. Actions implemented at lower levels of the education system to ensure that more Roma people access higher education will not translate into an increase in graduation rates if they are not accompanied by initiatives aimed at supporting these students once they reach university.

The Roma population is one of the most socially excluded communities [

9]. Specifically, the history of the Roma is marked by discriminatory episodes including imprisonment, spatial segregation, attempts at cultural assimilation and lack of recognition. These circumstances have led to a situation of social exclusion that is sustained by school dropout rates and low educational levels [

10]. In 2010, the European year to combat poverty and social exclusion, the Roma people were recognised as one of the groups with a higher risk of poverty in Europe. Therefore, this reality has consistently jeopardised their access to the labour market, housing, education, and political participation [

11].

International organisations have documented the existence of a considerable proportion of the Roma population of working age that lacks the necessary academic credentials to qualify for quality employment [

12,

13,

14]. Labour inclusion is closely related to educational attainment, and various indicators pointing to this link have become even stronger over the years. For example, the European Council predicted that by 2020, 16 million non-core jobs would require high qualifications, while the demand for low-qualification jobs would decrease by 12 million [

15].

The European Commission [

16] states that the profile of students entering and completing higher education must reflect social diversity. This requires the intervention of governments, educational centres and higher education institutions in adopting actions to increase the presence of underrepresented students. Increasing the inclusiveness of higher education systems requires the creation of the necessary conditions for the success of students from different social backgrounds. However, universities still need to make profound changes to become inclusive and egalitarian institutions [

17]. Indeed, beyond the issue of financial support for disadvantaged groups, actions need to be taken to guarantee that campuses are free from discrimination, develop mechanisms aimed at the early detection of problems, promote flexible study alternatives, and recognise previous experience, among other measures (European Commission, 2017). Accordingly, Friedman and Garaz [

18] emphasised the importance of promoting scholarships and support programs for Roma students to encourage their social inclusion and reduce the inequalities faced by these communities, especially those from families with lower income levels and lower levels of education.

Increasing the university graduation rates of Roma students constitutes a powerful mechanism to fight the social exclusion of the Roma population given its multiplier effect on other areas. Since higher education is a vehicle to achieve highly qualified occupations, it can contribute to the social inclusion of this community and improvement of the social perception of Roma, favouring their access to areas of responsibility and decision-making. In fact, this is one of the main points that the Roma themselves argue when they refer to the importance of achieving university [

19].

The educational field has widely documented the key role of social referents in the educational expectations of children and, consequently, in their academic achievements [

20]. Therefore, the presence of Roma graduates in the community has the potential of a multiplier effect, as they become role models for their social group and raise the expectations of the Roma youth. Accordingly, the first individuals to complete higher education in communities with little academic tradition become references for all citizens and, especially, for their own community and its youth [

21]. Consequently, support to promote the effective graduation of Roma students who reach university can have an impact on the educational aspirations of Roma children and their inclusion in priority areas such as work, health and housing, and participation in society.

Research on the reality of Roma students in higher education remains scarce in Spain. Nevertheless, studies focused on the experience of university students belonging to ethnic minorities and/or first-generation students conducted in other countries indicate that these students face more obstacles than their peers [

22,

23,

24], including greater difficulties in navigating the university environment and understanding academic expectations and bureaucratic procedures [

22]. Additionally, there is a higher proportion of Roma individuals who are older on average, are part-time students, have family responsibilities and experience more financial difficulties in comparison to other students. These circumstances affect their experience within the university and prospects to complete their studies and often translate into significantly lower retention and graduation rates [

25].

The field work conducted by the Higher Education Internalisation and Mobility project (HEIM) [

26] analysed the trajectories of Roma university students and discussed some of the difficulties they faced. According to Padilla et al. [

27], the analysis of successful trajectories in a sample of Spanish students revealed a series of factors that can favour their university access (e.g., residence in a non-segregated urban context, high family educational aspirations, family support, and the presence of social referents who had reached university within their own family). The authors emphasised the need to develop more research on Roma university students and promote their visibility to counteract the traditional homogenised and simplified perception of the Roma population.

Initiatives to guarantee equitable access to education highlight the importance of scholarship programs for the Roma community. However, beyond some isolated scholarship programs, there is a lack of truly effective initiatives aimed at guaranteeing Roma students access to higher education in Spain and in most EU countries: “the EU Roma Framework and its corresponding national strategies should have aimed for clear indicators and systematic measures to diminish discrimination and increase the participation of Romani youth in higher education” [

28,

29].

Other studies on university students from ethnic minorities show the psychological stress that these students experience during their time at university, as a result of the barriers to access higher education, the discrimination faced at university, the perceived pressure due to the need to prove their worth and the desire to fulfil the high expectations that their communities have placed on them [

30].

In addition to the difficulties of belonging to an ethnic minority in a hierarchical society, Roma students often come from backgrounds which are unfamiliar with academia. Therefore, the barriers of belonging to an ethnic minority coexist with those faced by first-generation university students. Furthermore, because they often come from contexts of economic and social exclusion, they face greater economic difficulties, relying on scholarships or paid work more often than other university students.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Objectives

The project “Roma in the Spanish university: Difficulties and actions to overcome them” (UNIROMA) was developed between 2019 and 2022. Its main purpose was to analyse the situation of Roma students in Spanish universities, a topic that has been scarcely studied even though the Roma people are the most important minority ethnic group in the country and in the European Union.

The project aimed to identify the profiles of Roma students at Spanish universities, study the difficulties they faced and formulate recommendations to support these students in graduating from university. This article presents the results of the first phase of the project, which had the main objectives of identifying the profiles of present Roma university students in Spain and exploring their university experience.

Concretely, the objectives of this phase of the research project were as follows:

- (1)

Identify the profiles of Roma students currently enrolled in Spanish universities.

- (2)

Study the university experience of the Roma students in the sample:

Examine their university attachment.

Capture experiences of discrimination faced at university.

Explore their academic expectations and future aspirations.

This study is aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the UN (especially goals 4 and 10), and the goals of the European Strategy for 2030, because the educational exclusion of the Roma population is a major problem with important social and employment consequences.

3.2. Methodology

The study followed the communicative methodology, which seeks to analyse reality and contribute to its transformation through the engagement of the different social agents involved in all stages of the research: from the design of the data collection tools, the analysis of the results and the formulation of policy recommendations [

31]. To this end, an Advisory Council was set up at the very beginning of the research, made up of Roma university students, professionals with experience in university management and representatives of Roma associations (CampusRom Network of Catalonia and National Federation of Roma Associations “Kamira”).

The project was based on a mixed-methods approach that combined quantitative and qualitative techniques, including online questionnaires, interviews and focus groups. This article presents the results of the questionnaire administered to Roma university students enrolled in Spanish universities at the time of the study.

3.3. Design and Instruments

The data collection was conducted by means of an online questionnaire based on previous surveys conducted with university students in general and with ethnic minority students in particular [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. These models were discussed in focus groups held with Roma university students and with the Advisory Board to design a first draft of the questionnaire. After its elaboration, it was validated by piloting to ensure its feasibility, reliability and validity, as well as to adjust the time required to complete it.

The questionnaire, which took respondents an average of 15 min to complete, contained 73 questions divided into the following sections:

- ▪

Introductory: 4 multiple-choice questions

- ▪

Academic aspects: 26 questions (9 open-ended, 17 multiple-choice)

- ▪

Interactions and inclusion: 14 questions (3 open-ended, 11 multiple-choice)

- ▪

Future expectations and aspirations: 4 questions (1 open-ended, 3 multiple-choice)

- ▪

Barriers: 2 questions (1 open-ended, 1 multiple-choice)

- ▪

Sociodemographic: 23 questions (7 open-ended, 16 multiple-choice).

The questionnaire was administered electronically through LimeSurvey from May to July 2020. The COVID-19 lockdown did not modify the initial design. Because the initial plan was to conduct an online survey, it was not affected by mobility and gathering restrictions. However, given the requirements that online education posed, we introduced questions about the availability of resources at home, such as computers, internet connections and study space. Univariate descriptive analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS statistics version 25.

The research assumed the ethical criteria of scientific research by applying the ethical codes of the International Sociological Association and the European Sociological Association.

3.4. Sampling

The electronic questionnaire was administered among Roma individuals enrolled in formal studies at a Spanish university at the time of data collection, and 98 valid responses were obtained (n = 98; 95% CI; standard error 9.58%). Because no ethnic data are collected in Spain, it was not possible to perform probability sampling. Thus, following the recommendations of research with hard-to-reach populations [

37,

38,

39], we used snowball sampling.

We highlight the great difficulties encountered in accessing the sample, given the small size and dispersion of the target population. The main means to reach respondents were Roma associations and support groups and social media.

3.5. Description of the Sample

Data were obtained from students at 33 universities in 12 regions, with Catalonia, Andalusia and Valencian standing out. These three regions happen to be the three with the largest Roma population according to estimations [

40].

Regarding age and gender distribution, the sample was made up of 51% men and 49% women, with a mean age of 26.7 ± 0.75 years (SD 7.3 years), and no significant differences by sex (26.28 ± 1.12 years for women and 27.06 ± 1.03 for men).

The socioeconomic data of the participants offer a picture of the general Roma population in Spain: large family units with low economic capital and levels of education.

Participants lived in large family units, with an average of 4.26 ± 18 (SD 1.73) members per household. Most lived with their parents and/or siblings (50%) or with extended family (9%). However, 37% were emancipated and lived with a partner (26% with children and 5% without children) or alone (6%).

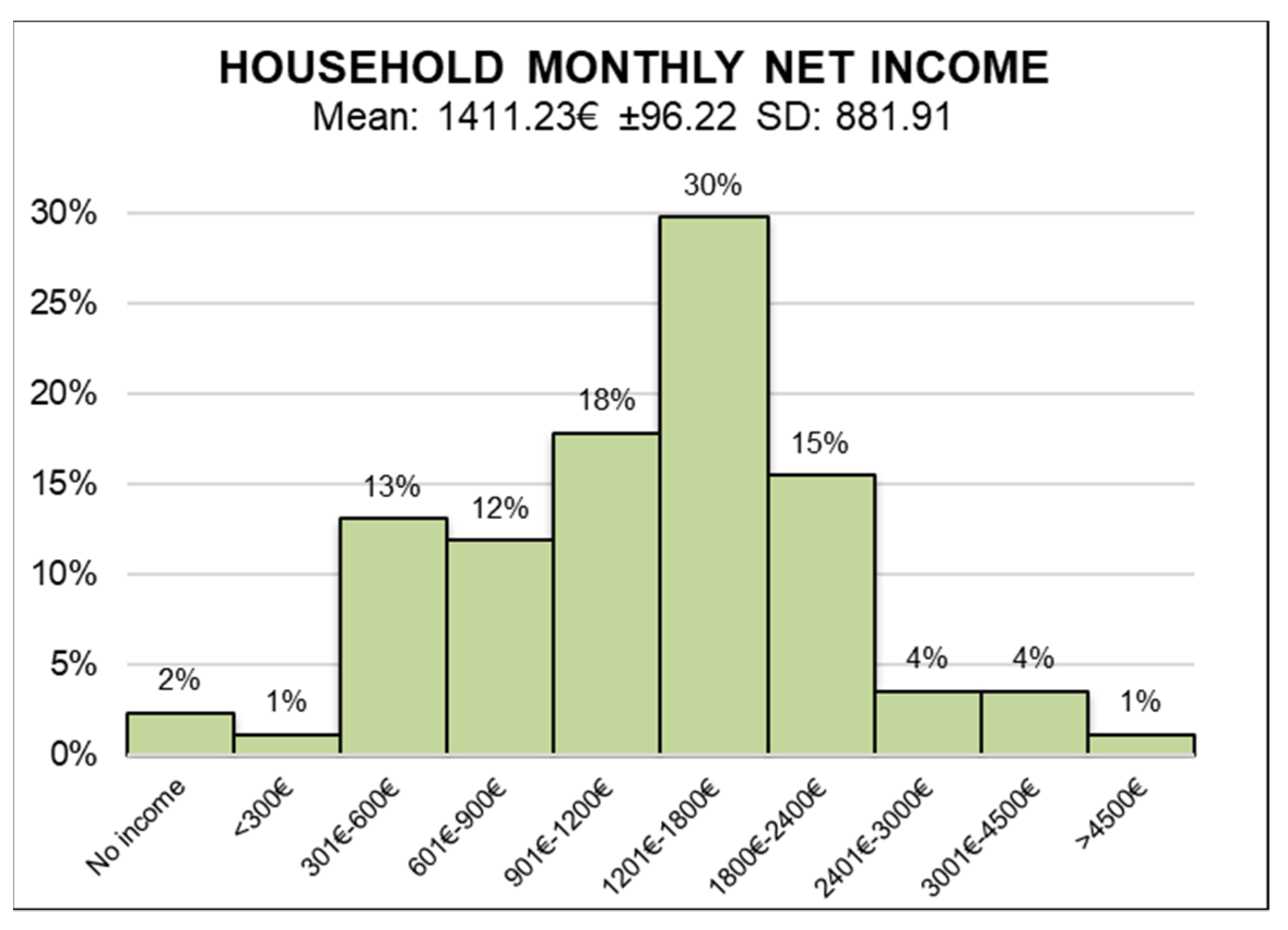

According to the data about income, the average monthly net income of the sample was EUR 1411.23€ ± 96.22 (see more in

Figure 1), reflecting a situation of vulnerability in terms of economic resources. In line with this economic situation, 69% were beneficiaries of scholarships and/or academic financial support from the government or other public and private sources.

This economic situation translated into a lack of available resources for academic purposes, as shown in

Figure 2. This aspect has been of special relevance in recent years due to university closures and attendance restrictions derived from the COVID-19 pandemic. Hence, we observed that 55% of the respondents lacked a quiet space to study, 9% did not have a broadband internet connection and 36% did not have a computer for their exclusive use.

Participants in our study were mostly first-generation university students and came from families with low levels of education. Sixty-seven percent had parents with primary education or less, 26% had parents who had secondary studies, and only 4% had parents with a university background. See

Figure 3 for details.

4. Results

The survey aimed to identify the profiles of Roma students currently enrolled in Spanish universities and their experience in university, with a special focus on the experiences of discrimination faced at university.

4.1. Students’ Profiles: Traditional vs. Non-Traditional Students

The literature on higher education distinguishes between traditional and non-traditional students. Traditional students are those who arrive at the university immediately after finishing high school and whose main activity is studying. In addition, they do not have family responsibilities and do not work or they work part-time. Non-traditional students are those who have different ages or life situations in comparison with most university students. Specifically, the National Centre for Education Statistics [

41] defines non-traditional students as those who meet any of the following conditions: (a) late entry; (b) attend college part-time; (c) combine studies with a full-time job; (d) are financially independent; (e) have dependents or (f) do not have a high school diploma.

Figure 4 shows the criteria followed to assign participants to each of the profiles. Traditional students included those who accessed university from age 17 to 24 by the mainstream Spanish educational system routes (high school, baccalaureate, vocational training) and for whom studying was the main occupation; they do not have family responsibilities and do not work, or they just work part-time. These constitute 42% of the participants in the survey. The remaining 58% of the sample were non-traditional students, although they belong to two very differentiated categories in terms of university experience and needs. On the one hand, we identified mature students who had accessed university when they were over 24 years of age (51% of the sample). On the other hand, we found young students who started university at the ages of 17 to 24 by the mainstream access routes but for whom studying was not their main occupation because they had family responsibilities and/or worked full-time (7% of the sample).

The main route of access to university in our sample, in line with the university population in general, was the baccalaureate program. However, the access routes were diverse, as a high proportion had accessed university through rutes aimed at mature students. According to data from the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (2019), in Spain the main access routes to university are those of baccalaureate and vocational training, which together represent 91% of admissions. These percentages are significantly lower in our sample, representing 71% (49% high school and 22% vocational training). The remaining 29% had taken alternative routes, among which access for people over 25 years of age stood out, with 26% (in general statistics this route only represents 1.3%). In line with these results, it is remarkable that almost 30% of our respondents had only completed compulsory education by the time they started university.

4.2. Academic Information

Regarding their current studies, 93% of students were pursuing a degree, while 5% were master’s students and 2% were doctoral students. The distribution by areas of knowledge showed that most were enrolled in social and legal sciences (71%), followed at a great distance by health sciences (13%), arts and humanities (9%), natural and experimental sciences (4%) and engineering and architecture (2%). These results are consistent with other studies, such as the one conducted by Garaz and Torotcoi (2017) with Roma university students in Eastern European countries.

Among the main motivations for studying, the desire to improve job prospects stood out, having been mentioned as one of the main reasons by 84% of the participants. Next, more than half of the students mentioned the desire to improve the life of the community and the desire to learn, with 53% each. With lower percentages we found: “to improve my economic situation” (44%); “to feel fulfilled” (41%); “to show that I am capable of studying” (34%); “to feel useful” (25%) and “to help my children” (24%).

For the people who had encouraged the participants to study, parents stood out (63%), as well as other family members (35%). Next, as agents also relevant in the decision to go to university, other acquaintances (27%), teachers (26%) and members of associations (22%) were mentioned.

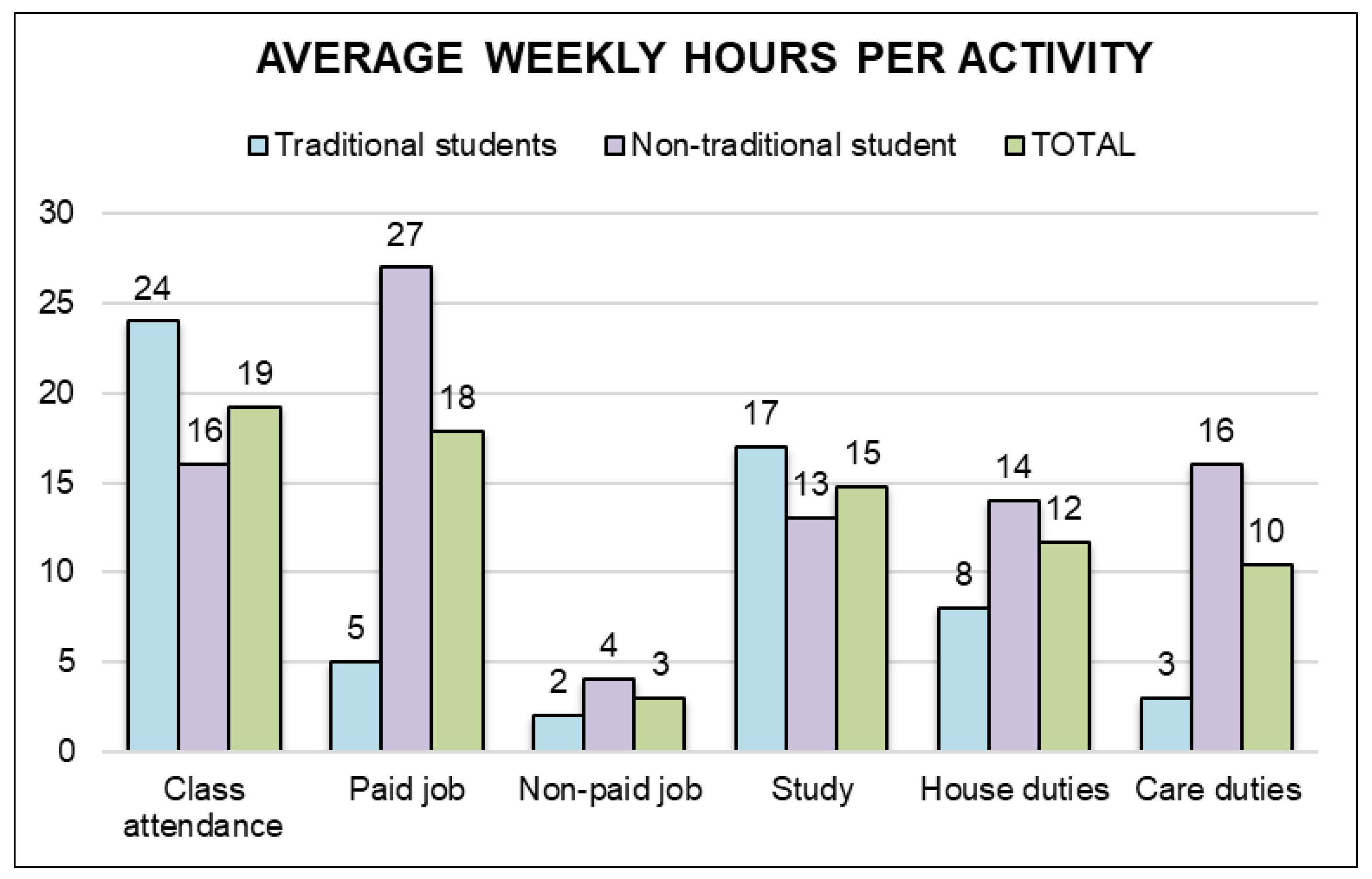

As is frequent among ethnic minority and first-generation students, the academic dedication of Roma students is marked by the need to combine their studies with other obligations, especially work and/or family duties. The analysis of the uses of time in our sample reflected this situation, especially among non-traditional students. Thus, we found that they attended classes an average of 19 ± 1.26 h per week, with significant differences according to profile (24 ± 1.54 h for traditional students and 16 ± 1.76 h for non-traditional students). The same happened with the hours dedicated to studying and performing autonomous class tasks, where the general average was 15 ± 1.07 h per week, with a difference of 4 h (17 ± 1.67 h for traditional students vs. 13 ± 1.37 h for non-traditional students). Regarding the differences by gender, although we found differences in the number of hours of class attendance (21 ± 1.99 h for women and 17 ± 1.56 h for men), they were not observed in the hours of autonomous study, which were 15 h on average in both cases.

Participants showed great dedication both to paid work (18 ± 1.68 h per week) as well as to household chores (12 ± 1.34 h) and care (10 ± 1.55 h). In this case, there were significant differences between traditional and non-traditional students, with averages of 5 ± 1, 8 ± 1.52 and 3 ± 0.99 for the former compared to 27 ± 2.04, 14 ± 1.98 and 16 ± 2.31 for the latter. Regarding the distribution by gender, men reported a higher dedication on average to paid work—21 ± 2.45 h for men versus 15 ± 2.24 for women—while the trend was reversed in relation to housework and care—6 ± 0.69 h and 9 ± 1.85, respectively, for men, compared to 18 ± 2.34 h and 12 ± 2.5 for women—(details can be seen in

Figure 5).

4.3. University Attachment

The data obtained enabled the identification of dimensions related to the attachment participants have with their universities: academic engagement, interactions, satisfaction, self-efficacy, identification and participation.

Figure 6 details the operational model followed, which was based on previous studies about university students’ attachment [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36].

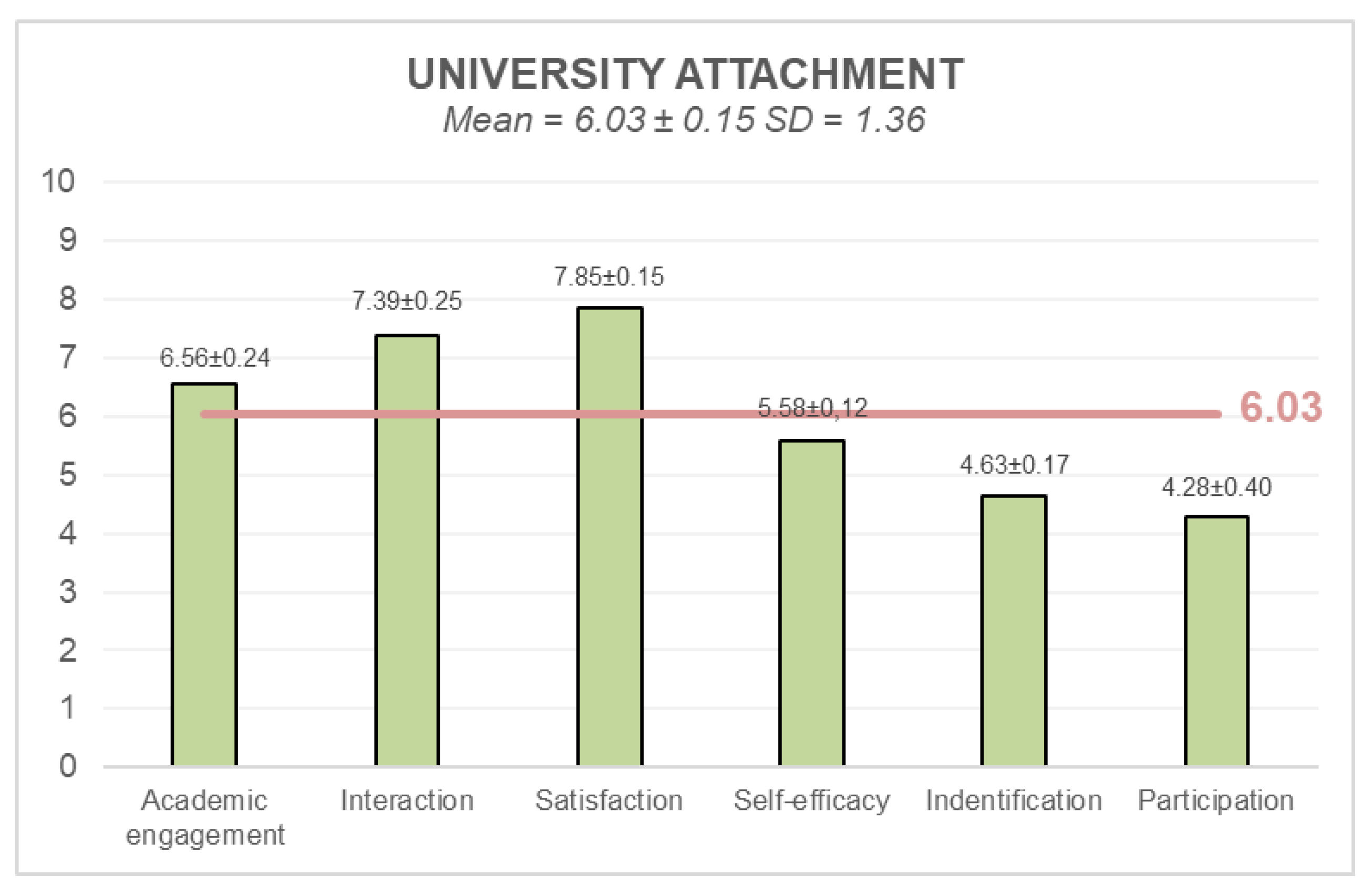

On a scale of 1 to 10, the mean university attachment of participants in this study was 6.03 ± 0.15. The dimensions that stood out were satisfaction (7.85 ± 0.15) and social interactions (7.39 ± 0.25). In contrast, the dimensions identified as detrimental for university attachment were participation (4.28 ± 0.4) and identification (4.63 ± 0.17). Roma students participating in this study reported a lack of cultural identification with an institution where Roma culture is not present at all.

Figure 7 shows the average for each dimension.

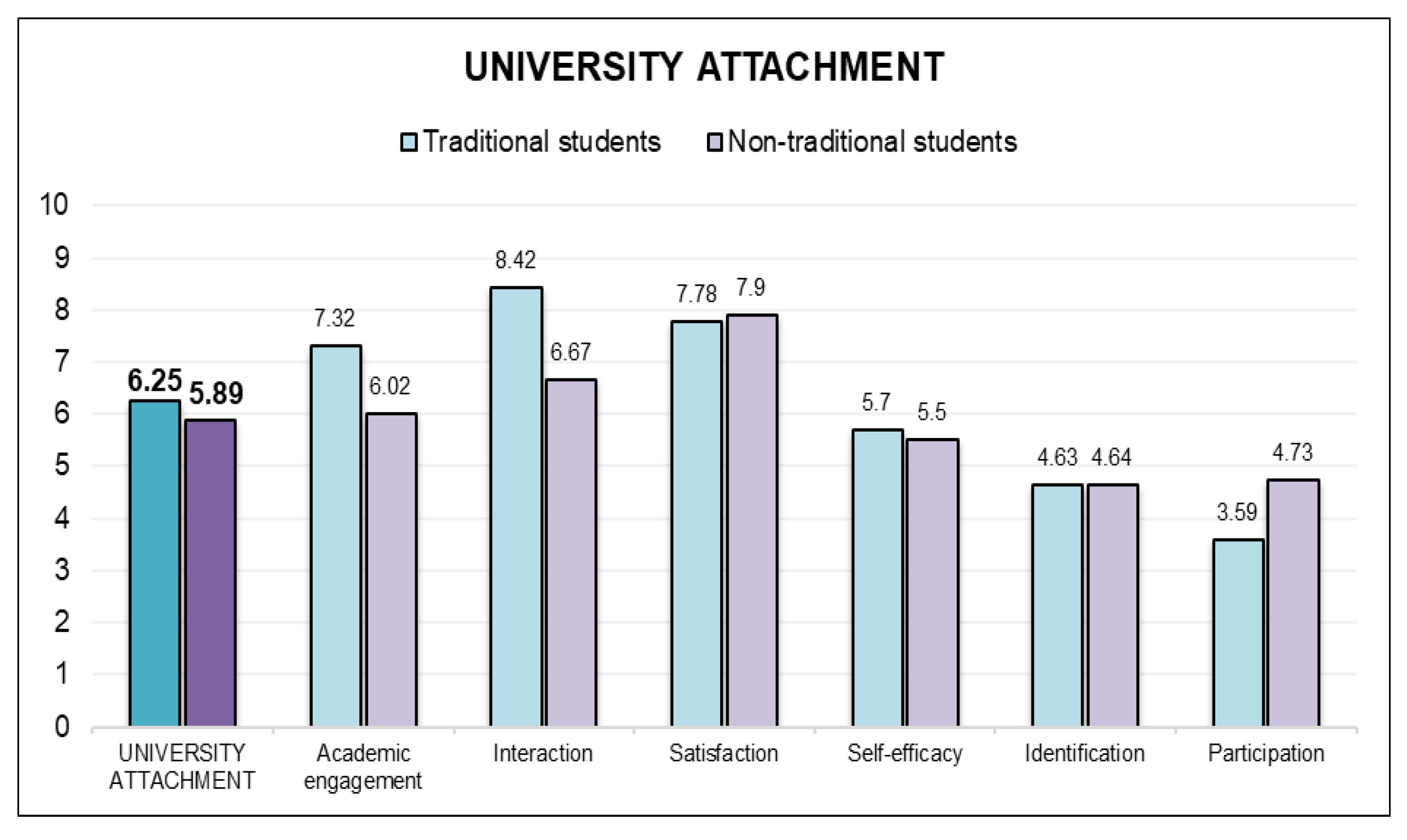

When analysed by gender, the results show that men presented a stronger attachment than women (6.18 ± 0.2 for men and 5.87 ± 0.22 for women). However, in certain dimensions, such as academic engagement, interaction and identification, women scored slightly higher, whereas men scored higher in self-efficacy and participation. In fact, the dimension with a larger difference is the latter, where women scored 3.64 ± 0.57 and men scored 4.88 ± 0.56, a difference that points to the traditional underrepresentation of women in the sphere of public participation.

Regarding student profiles, traditional students showed a stronger attachment (6.25 ± 0.22) than non-traditional students (5.89 ± 0.20). As mentioned in the previous section, non-traditional students have other responsibilities such as jobs and family, resulting in less dedication to university than traditional students. This affects not only academic engagement but also social interactions, which were the two aspects in which non-traditional students in the sample scored lower (6.02 ± 0.34 and 6.67 ± 0.3, respectively) than traditional students (7.31 ± 0.31 and 8.42 ± 0.32, respectively). Non-traditional students obtained remarkably higher scores in participation (4.73 ± 0.50 compared to the 3.59 ± 0.66 of traditional students). Nevertheless, the dimensions of satisfaction, self-efficacy and identification were similar in both profiles (7.78 ± 0.26; 5.7 ± 0.18 and 4.63 ± 0.23, respectively, for traditional students versus 7.9 ± 0.19; 5.5 ± 0.17 and 4.64 ± 0.24, respectively, for non-traditional students). Details can be seen in

Figure 8.

4.4. Discrimination at University

At the institutional level, the students interviewed rated the institution’s capacity to incorporate cultural diversity in general and the Roma culture in particular as unsatisfactory. On a scale of 1—“strongly disagree” to 5—“strongly agree”, we obtained an average of 3.71 ± 0.1 for the statement “people like me are welcomed at this university” and 3.18 ± 0.13 for the perception of the degree to which the university reflects the cultural diversity of society. The lowest rated aspects were those directly related to the presence of Roma individuals and culture, both at the university in general and in the content, with averages of 1.72 ± 0.11 and 1.56 ± 0.11, respectively. Specifically, in relation to the presence of Roma culture in the academic content, 83% of the participants rated it as 1 or 2, while only 6% rated it as 4 or 5.

Although, as pointed out above, in general terms the participants show a fairly high degree of inclusion, a significant percentage reported having felt excluded in certain situations, for example, when having to form work groups. Specifically, 41% reported having felt discriminated against, either occasionally (37%) or frequently (4%). Regarding the forms of discrimination, 24% reported having experienced verbal violence, 1% physical violence and 26% other forms of discrimination. The qualitative fieldwork will further elaborate on what these other forms are. In any case, in the open question for those who marked “other forms,” most of them stated that they had felt discriminated against by comments, both from students and teachers, reproducing stereotypes about the Roma community, with phrases such as “Gypsies are...” or using the word Roma as a synonym for thief. By profile, the perception of discrimination was similar, although slightly higher among traditional students. Likewise, men reported having felt discriminated against more frequently than women.

According to the responses obtained, ethnic origin was the main factor of discrimination. Thus, 40% said they had felt discriminated against because of their ethnic group. Other sources of discrimination were age (7%), socioeconomic level (4%), sex or gender (2%) and other reasons (1%).

Table 1 summarises the responses of participants in this matter.

Significant differences were found in the reasons for which they felt discriminated against according to sex. Thus, men reported having felt discriminated against more than women for being Roma and because of their age, while women had felt more discriminated against because of their sex/gender. In terms of profile, traditional students perceived more ethnic and gender discrimination than non-traditional students, while the latter felt more discriminated against because of their age. Regardless, the main reason given for discrimination was, by far, ethnicity.

The perception of discrimination suffered by the Roma community in society and in academic circles is perhaps what leads some to sometimes hide the fact that they are Roma. Specifically, 12% of the students who responded to the survey affirmed that they had intentionally concealed it at some time. All of them pointed to fear of rejection or being discriminated against as the reason for hiding their ethnicity.

4.5. Expectations and Academic Aspirations

Data showed that participants held high academic expectations, with confidence that they would finish the degree they were pursuing at the time of the study: 85% affirmed they believed they would probably finish the current degree, 14% did not know and only 1% believed that they would probably not finish. These high academic expectations were also appreciated in relation to the intention to continue studying after graduation, as reflected by the fact that 92% intended to continue studying, whether a master’s or doctoral degree (62%), a second degree (9%) or other type of studies (8%).

Although the differences with respect to future academic expectations by gender and profile were small, there were somewhat higher expectations among women and among non-traditional students, both in relation to the completion of current studies and to subsequent continuation.

5. Discussion

Although there is a wide array of scientific literature on the difficulties Roma face in the educational field, there is a lack of knowledge about those students who succeed in getting into Spanish university. According to the data obtained, Roma university students participating in this research were, in general terms, older, had more family and work responsibilities and came from families with lower educational levels and more limited economic resources than average university students. These data are consistent both with studies about the Roma population in Spain [

7] and with the international literature on university students from ethnic minorities and/or first-generation students [

25].

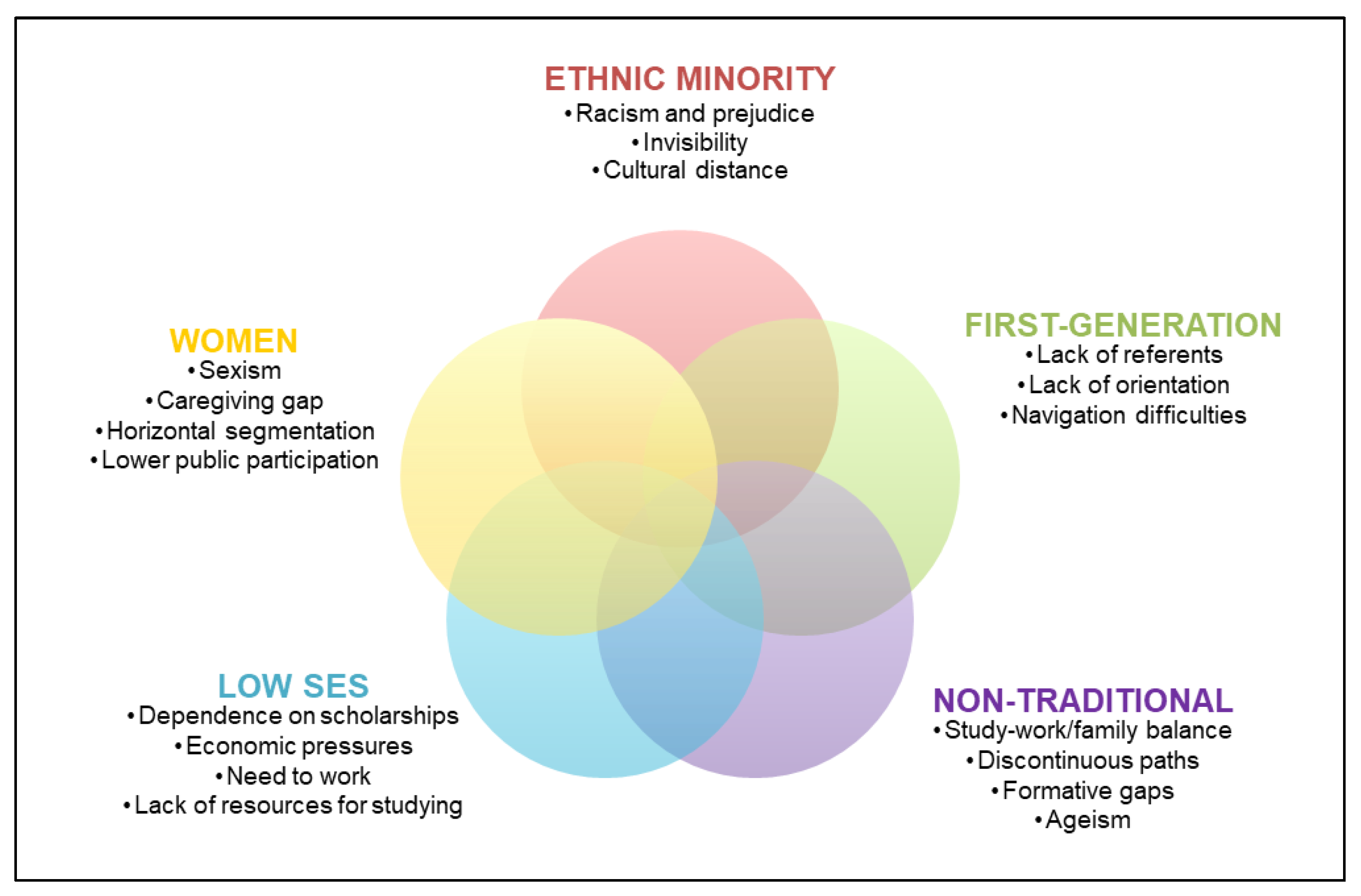

These findings show that Roma university students experience the intersectionality of multiple discrimination factors, namely belonging to an ethnic minority, being first-generation students, having limited economic and material resources and having had, more frequently than the average, discontinuous academic paths. Each of these circumstances adds specific barriers that hinder university graduation. In addition, in the case of women, barriers related to sex discrimination add specific difficulties. A summary of these factors can be seen in

Figure 9.

Data in Spain show how most Roma students do not make it into university (Fundación Secretariado Gitano, 2013) due to the multiple stereotypes and low educational expectations they have faced since young ages [

20,

42]. However, those who enter university also encounter bigger challenges because of being Roma. These barriers include feeling that they are in unreceptive institutions [

43], hiding their ethnicity under stress because of the fear of discrimination [

44] and not feeling like they belong due to anti-Roma comments and attitudes [

45], among others. Thus, ensuring a safe climate where these students’ well-being is guaranteed is important for increasing the share of underrepresented communities’ students [

46], as well as including their voices in educational institutions from an early age [

47].

Second, they are more frequently non-traditional students, having the need to combine studies with occupations in the labour market and/or family commitments. Thus, conciliation with their other duties may hinder their academic performance [

48], and they are more likely to drop out of university [

49] (Hottinger and Rose, 2006). In addition, a high proportion of the participants reported discontinuous educational trajectories, which translates into gaps in areas such as knowledge of foreign languages and technologic skills. Being older may also pose a difficulty, as ageism is present in higher education to the detriment of older students [

50]. Universities tend to be conceived and designed for traditional students, who are not emancipated and for whom studying is their main activity. The rigidity of Spanish university structures hinders the university careers of other students, increasing educational inequality by favouring those who have sufficient means, generally provided by families, to be able to dedicate themselves exclusively to studies [

51]. This is of special relevance for the Roma community because it is a group with significant economic needs and they rarely receive from their families the necessary economic support to dedicate their time exclusively to university.

Third, most respondents (as well as most individuals from ethnic minorities) were first-generation students. Scientific literature has shown that first-generation students tend to have lower academic engagement and retention [

52] due to increased difficulties in navigating the university environment and understanding academic expectations and bureaucratic procedures, and a lack of referents and acquaintances to seek orientation, among others. A mismatch between first-generation students’ culture and the university culture, based on independence, is linked to poorer academic performance; first-generation students do not have a close figure to guide them through the institution [

53]. In this vein, the case of Roma referents is especially relevant [

27]; many of them do not even dream of entering university because of the lack of social referents in their communities [

54]. Nevertheless, the multiplying effect Roma university students have in their contexts has also been evidenced, encouraging others to do the same by showing them it is possible [

55,

56].

Finally, participants in the study reported a vulnerable economic situation. It has been widely studied how low-SES students have fewer opportunities for academic success in higher education [

57,

58]. These data are consistent with the socioeconomic position of the Roma population in Spain, which represents a barrier to pursuing post-compulsory studies. In addition, the dependence on scholarships usually represents an added pressure for university students, given the strict academic criteria imposed to maintain them, which, in the case of Spain, are difficult to meet, especially for those students who must combine their studies with work and/or family obligations. Moreover, the growing importance of virtual academic activity that we have experienced in recent years, which has been particularly evident due to COVID-19 precautionary measures, that shifted much of university education to virtual or hybrid formats, has resulted in a greater reliance on technological resources and appropriate study space. Actions taken in this regard should always consider the effects on particularly vulnerable populations to avoid increasing the educational gap.

In addition to these factors, women also face sexism that creates specific barriers. As our data revealed, the caregiving gap results in a significant increase in time devoted to household chores and care duties, reducing the available time for academic activities. Another element to be considered is horizontal segmentation, which results in different proportions of men and women depending on the type of studies. This difference, which has been identified in our survey, hinders future gender equality because, as research points out, women are underrepresented in the degrees that maximise future returns [

59]. Finally, we have also identified a lower degree of participation of women in student associations and the university governing bodies, also agreeing with the traditional underrepresentation of women in leadership positions. There is still a long way to go to achieve equality between Roma and non-Roma populations’ educational levels. Many stigmas, such as depictions of the Roma population as having no interest in education, persist. However, supporting those Roma who reach university is of major importance in terms of educational equity. The intersectionality of discriminatory factors they face translates into a multiplicity of barriers that hinder their opportunities to succeed. Reversing this situation is important, not only for these students but also for younger generations of Roma, because they can become referents within their community. Moreover, higher education is the means through which they can become qualified professionals and, therefore, enhance the participation of Roma in decision-making processes and contribute to overcoming the stigmatized view that mainstream society has of them.

The study presented here provides valuable insights to be considered by Spanish educational administrations when implementing policies to promote equity in higher education. The underrepresentation in universities of the largest ethnic minority in Europe requires the adoption of specific actions to address the situation. Given the barriers identified in this survey, these initiatives need to include measures to provide economic and academic support—through orientation or mentoring programmes and scholarships and loans, as well as actions to increase the cultural sensitiveness of universities, such as sensibility campaigns or professionals’ training programmes. Combating prejudice and racism and increasing the presence of the Roma culture is necessary to promote inclusiveness within universities.

7. Conclusions

This study identified the different profiles of Roma university students in Spain through an online questionnaire. Despite the limitations noted, the data obtained allowed us to respond to the objective of identifying the profiles of Roma students enrolled in Spanish universities, which will be the basis of the purposeful sampling for the qualitative phase. Additionally, it has allowed us to study their experiences at university, main barriers, experiences of discrimination and aspirations. The data obtained provide evidence of the existence of specific barriers that hinder the educational opportunities of Roma university students and, consequently, demonstrate the need to implement actions to support them. To be effective, the actions adopted must start from the knowledge of who these students are, and what their needs are, acknowledging the intersectionality of the barriers they face, not only due to their belonging to an ethnic minority but also because they are more frequently non-traditional, first-generation, and low-SES students. Women also face barriers due to the persistence of sexism. All these barriers will be further explored through semi-structured in-depth interviews during the qualitative phase.

The research presented here tackles a population that has never been studied in Spain. Therefore, it constitutes an exploratory work that needs to be complemented with further research on the topic. Future studies based on qualitative methods need to be conducted with the objective of defining in more depth the type of policies that address the needs of Roma students and are feasible in the Spanish context.