A Structural Model to Explain Influences of Organisational Communication on the Organisational Commitment of Primary School Staff

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Organisational Commitment

2.2. Organisational Communication

2.3. Organisational Communication and Organisational Commitment

3. Materials and Methods

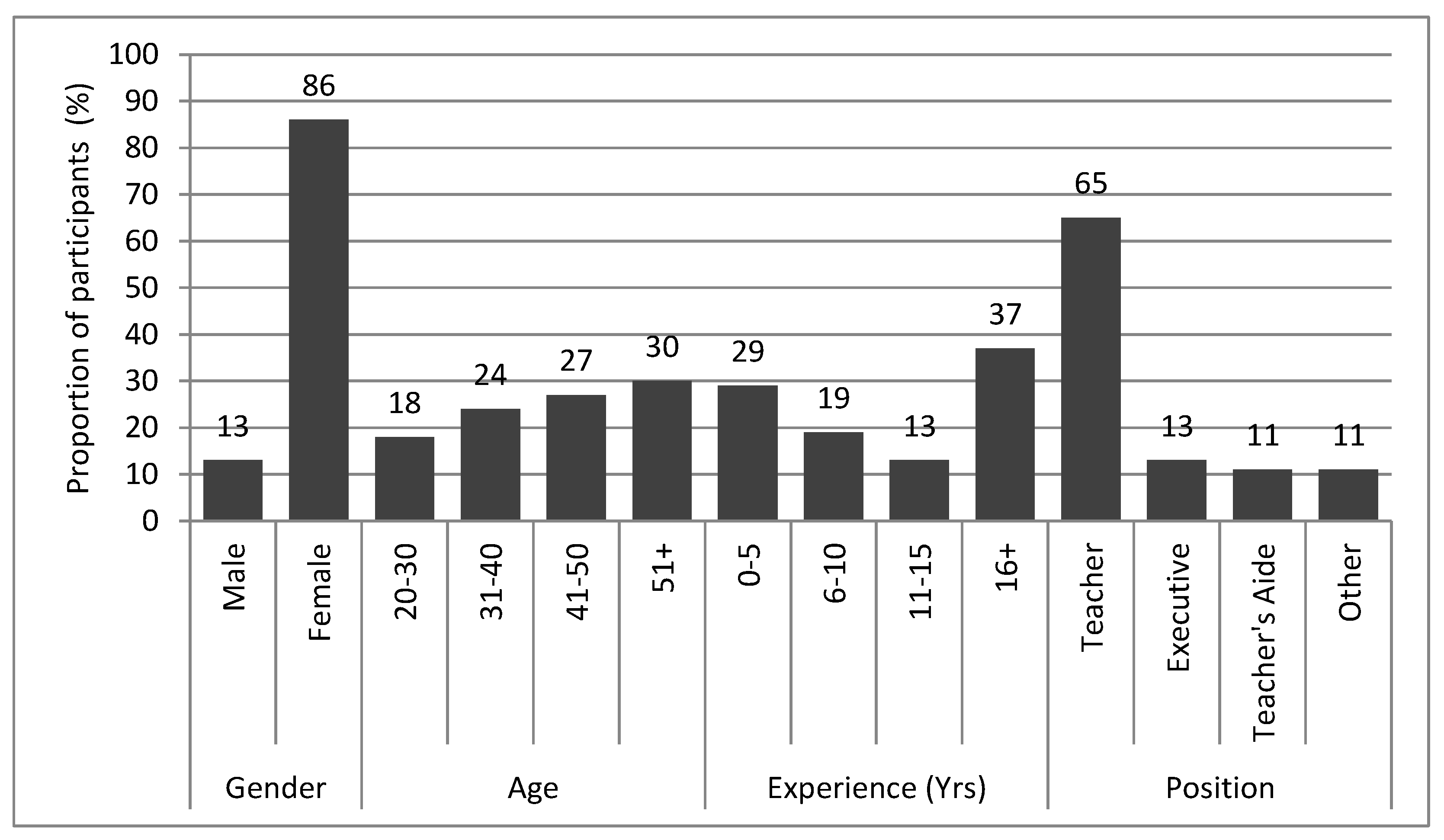

3.1. Sample

3.2. Instruments

3.3. Analyses

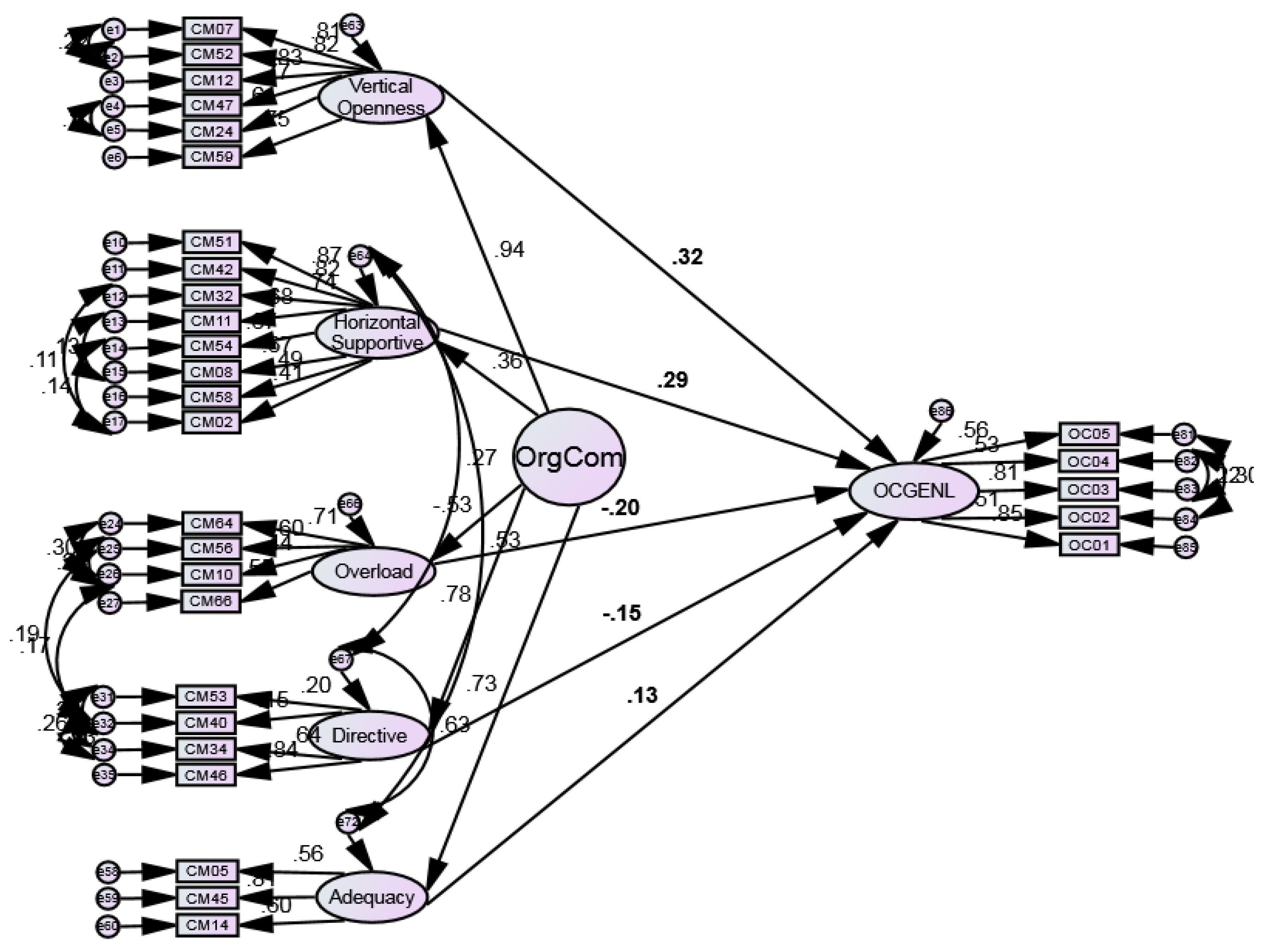

4. Results

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Collie, R.J.; Shapka, J.D.; Perry, N.E.; Martin, A.J. Teachers’ psychological functioning in the workplace: Exploring the roles of contextual beliefs, need satisfaction, and personal characteristics. J. Educ. Psychol. 2016, 108, 788–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerrim, J.; Sims, S. When is high workload bad for teacher wellbeing? Accounting for the non-linear contribution of specific teaching tasks. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2021, 105, 103395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roffey, S. Pupil wellbeing—Teacher wellbeing: Two sides of the same coin? Educ. Child Psychol. 2012, 29, 8–17. [Google Scholar]

- Shine, K. Reporting the ‘exodus’: News coverage of teacher shortage in Australian newspapers. Issues Educ. Res. 2015, 25, 501–516. [Google Scholar]

- Arnup, J.; Bowles, T. Should I stay or should I go? Resilience as a protective factor for teachers’ intention to leave the teaching profession. Aust. J. Educ. 2016, 60, 229–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, J.; Prescott, A.; Schuck, S.; Aubusson, P.; Burke, P.; Louviere, J. Teacher retention and attrition: Views of early career teachers. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 2013, 38, 112–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, R.; Greer, L.; Akbar, D.; Dawson, M.; Lyons, T.; Purnell, K.; Tabert, S. Attracting and Retaining Specialist Teachers and Non-Teaching Professionals in Queensland Secondary Schools: A Report to the Queensland Department of Education and Training; Queensland Department of Education and Training: Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 2009.

- Aspland, T. We Can’t Afford to Ignore the Teacher Exodus. ABC News, 4 February 2016. Available online: http://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-02-04/aspland-we-cant-afford-to-ignore-the-teacher-exodus/7139130 (accessed on 1 June 2017).

- Carey, A. ‘Rewarding’, but Four in Five Teachers Consider Quitting in Pandemic. The Age. 29 October 2021. Available online: https://www.theage.com.au/national/victoria/Rewarding-but-four-in-five-teachers-consider-quitting-in-pandemic-20211028-p5940j.html (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Stroud, G. Why do Teachers Leave? ABC News. 4 February 2017. Available online: http://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-02-04/why-do-teachers-leave/8234054 (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Mason, S.; Matas, C.P. Teacher attrition and retention research in Australia: Towards a new theoretical framework. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 2015, 40, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weldon, P.; Ingvarson, L. School Staff Workload Study: Final Report to the Australian Education Union—Victorian Branch; The Australian Council for Educational Research Ltd.,: Camberwell, VIC, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerial Advisory Council on the Quality of Teaching (MACQT). Raising the Standard of Teachers and Teaching; MACQT: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Polesel, J.; Rice, S.; Dulfer, N. The impact of high-stakes testing on curriculum and pedagogy: A teacher perspective from Australia. J. Educ. Policy 2014, 29, 640–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinson, T. Inquiry into the Provision of Public Education in NSW: First Report; Pluto Press and New South Wales Teacher Federation: Darlinghurst, NSW, Australia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL). What do we Know About Early Career Teacher Attrition in Australia? 2016. Available online: https://www.aitsl.edu.au/docs/default-source/aitsl-research/spotlights/spotlight-on-attrition-august-2016.pdf?sfvrsn=6 (accessed on 1 June 2017).

- Heffernan, A.; Longmiur, F.; Bright, D.; Kim, M. Perceptions of Teachers and Teaching in Australia; Monash University: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Obeng, A.F.; Zhu, Y.; Quansah, P.E.; Ntarmah, A.H.; Cobbinah, E. High-performance work practices and turnover intention: Investigating the mediating role of employee morale and the moderating role of psychological capital. SAGE Open 2021, 11, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K.; Hur, H. Bureaucratic structures and organizational commitment: Findings from a comparative study of 20 European countries. Public Manag. Rev. 2020, 22, 877–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daft, R.L.; Noe, R.A. Organizational Behavior; South Western Publishing: Mason, OH, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, L. Teacher Morale, Job Satisfaction and Motivation; Paul Chapman Publishing: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Luthans, F. Organizational Behavior, 12th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Morrow, P.C. Managing organizational commitment: Insights from longitudinal research. J. Vocat. Behav. 2011, 79, 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McShane, S.; Olekalns, M.; Travaglione, T. Organisational Behaviour, 4th ed.; McGraw-Hill: North Ryde, NSW, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J. A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 1991, 1, 61–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noe, R.; Hollenbeck, J.; Gerhart, B.; Wright, P. Human Resource Management: Gaining a Competitive Advantage, 12th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Roe, R.A.; Solinger, O.; Olffen, W.V. Shaping organizational commitment. In The Sage Handbook of Organizational Behavior Volume 2: Macro Approaches; Clegg, S.R., Cooper, C.L., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 130–149. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, S.A.; Poole, R.; Zibarras, L.D. Employee absence and organizational commitment. J. Pers. Psychol. 2012, 11, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weldon, P. Early career teacher attrition in Australia: Evidence, definition, classification and measurement. Aust. J. Educ. 2018, 62, 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morris, J.E.; Lummis, G.W.; Lock, G.; Ferguson, C.; Hill, S.; Nykiel, A. The role of leadership in establishing a positive staff culture in a secondary school. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2020, 48, 802–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lok, P.; Crawford, J. The effect of organisational culture and leadership style on job satisfaction and organisational commitment: A cross-national comparison. J. Manag. Dev. 2004, 23, 321–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bogler, R.; Nir, A.E. The contribution of perceived fit between job demands and abilities to teachers’ commitment and job satisfaction. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2015, 43, 541–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, P.C.; Wirth, R.E. Work commitment among salaried professionals. J. Vocat. Behav. 1989, 34, 40–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, M.B. Organisational and professional commitments: The influence in nurses’ organisational citizenship behaviours. Tekhne 2015, 13, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercurio, Z.A. Affective commitment as a core essence of organizational commitment: An integrative literature review. Hum. Res. Dev. Rev. 2015, 14, 389–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, N.; Youngs, P.; Frank, K. The role of school-based colleagues in shaping the commitment of novice special and general education teachers. Except. Child. 2013, 79, 365–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thien, L.M.; Razak, N.A.; Ramayah, T. Validating Teacher Commitment Scale using a Malaysian sample. SAGE Open 2014, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mowday, R.T.; Steers, R.M.; Porter, L.W. The measurement of organizational commitment. J. Vocat. Behav. 1979, 14, 224–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muchinsky, P.M.; Howes, S.S. Psychology Applied to Work, 12th ed.; Hypergraphic Press: Summerfield, FL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J.P.; Becker, T.E.; Vandenberghe, C. Employee commitment and motivation: A conceptual analysis and integrative model. J. Appl. Psychol. 2004, 89, 991–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Solinger, O.N.; Olffen, W.V.; Roe, R.A. Beyond the three-component model of organizational commitment. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yahaya, R.; Ebrahim, F. Leadership styles and organizational commitment: Literature review. J. Manag. Dev. 2016, 35, 190–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maia, L.G.; Bastos, A.V.B.; Solinger, O.N. Which factors make the difference for explaining growth in newcomer organizational commitment? A latent growth modeling approach. J. Organ. Behav. 2016, 37, 537–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marsh, C. Becoming a Teacher, 5th ed.; Pearson Education Australia: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, K.; Hudson, P.; Willis, J. How can principals enhance teacher job satisfaction and work commitment? In Proceedings of the Australian Association for Research in Education Conference: Speaking Back through Research, Brisbane, Australia, 30 November–4 December 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hulpia, H.; Devos, G.; Rosseel, Y.; Vlerick, P. Dimensions of distributed leadership and the impact on teachers’ organizational commitment: A study in secondary education. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 42, 1745–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somech, A.; Bogler, R. Antecedents and consequences of teacher organizational and professional commitment. Educ. Adm. Q. 2002, 38, 555–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, M.; Lovett, S. Sustaining the commitment and realising the potential of highly promising teachers. Teach. Teach. Theory Pract. 2015, 21, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P.E. Industrial and Organizational Psychology: Research and Practice, 6th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Thien, L.M.; Razak, N.A. Teacher commitment: A comparative study of Malaysian ethnic groups in three types of primary schools. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2014, 17, 307–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherkowski, S. Teacher commitment in sustainable learning communities: A new “ancient” story of educational leadership. Can. J. Educ. 2012, 31, 56–68. [Google Scholar]

- Yildirim, I. The correlation between organizational commitment and occupational burnout among physical education teachers: The mediating role of self-efficacy. Int. J. Progress. Educ. 2015, 11, 119–130. [Google Scholar]

- Jepson, E.; Forrest, S. Individual contributory factors in teacher stress: The role of achievement striving and occupational commitment. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2006, 76, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devos, G.; Tuytens, M.; Hulpia, H. Teachers’ organizational commitment: Examining the mediating effects of distributed leadership. Am. J. Educ. 2014, 120, 205–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boxall, P.; Purcell, J. Strategy and Human Resource Management, 3rd ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Crowther, F. From School Improvement to Sustained Capacity; Corwin: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Papa, M.J.; Daniels, T.D.; Spiker, B.K. Organizational Communication: Perspectives and Trends; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, E.M.; Goodall, H.L.; Trethewey, A. Organizational Communication: Balancing Creativity and Constraint, 5th ed.; St. Martin’s Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pincus, J.D.; Wood, S.C. The CEO-leader as relationship builder. In The IABC Handbook of Organizational Communication: A Guide to Internal Communication, Public Relations, Marketing and Leadership; Gillis, T.L., Ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2006; pp. 296–309. [Google Scholar]

- Shockley-Zalabak, P.S. Fundamentals of Organizational Communication: Knowledge, Sensitivity, Skills, Values, 8th ed.; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, J. The Business Communication Handbook, 8th ed.; Pearson: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, K. Organizational Communication: Approaches and Processes, 7th ed.; Cengage Learning: Stamford, CT, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Grunig, J.E.; Grunig, L.A. Characteristics of excellent communication. In The IABC Handbook of Organizational Communication: A Guide to Internal Communication, Public Relations, Marketing and Leadership; Gillis, T.L., Ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2006; pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- De Nobile, J. The 10C model of organisational communication: Exploring the interactions of school leaders. In Proceedings of the NZARE Annual Conference: ‘The Politics of Learning’/‘Noku Ano Te Takapau Wharanui’, Wellington, New Zealand, 20–23 November 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, C.E.; Weaver, W. The Mathematical Theory of Communication; University of Illinois Press: Urbana, IL, USA, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- De Nobile, J. Upward supportive communication for school principals. Lead. Manag. 2013, 19, 34–53. [Google Scholar]

- Jo, S.H. Teacher commitment: Exploring associations with relationships and emotions. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2014, 43, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nobile, J. The directive communication of Australian primary school principals. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2015, 18, 239–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlestig, H. Principals’ communication inside schools: A contribution to school improvement? Educ. Forum 2007, 71, 262–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somech, A. Directive versus participative leadership: Two complementary approaches to managing school effectiveness. Educ. Adm. Q. 2005, 41, 777–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikka, J.; Pitkäniemi, H.; Kettukangas, T.; Hyttinen, T. Distributed pedagogical leadership and teacher leadership in early childhood education contexts. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2021, 24, 333–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ibrahim, M.S.; Ghavifekr, S.; Ling, S.; Siraj, S.; Azeez, M.I.K. Can transformational leadership influence on teachers’ commitment towards organization, teaching profession and students learning? A quantitative analysis. Asia Pacif. Educ. Rev. 2014, 15, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadach, M.; Schechter, C.; Da’as, R. Instructional leadership and teachers’ intent to leave: The mediating role of collective teacher efficacy and shared vision. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2020, 48, 617–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nobile, J. Organisational communication and its relationships with job satisfaction and organisational commitment of primary school staff in Western Australia. Educ. Psychol. 2017, 37, 380–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dee, J.R.; Henkin, A.B.; Singleton, C.A. Organizational commitment of teachers in urban schools: Examining the effects of team structures. Urban Educ. 2006, 41, 603–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoy, W.K.; Miskel, C.G. Educational Administration: Theory, Research, and Practice, 9th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, M.; Huang, Y.; Qalati, .S.A.; Shah, S.M.M.; Ostic, D.; Pu, Z. Effects of information overload, communication overload, and inequality on digital distrust: A cyber-violence behavior mechanism. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 643981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atouba, Y. How does participation impact IT workers’ organizational commitment? Examining the mediating roles of internal communication adequacy, burnout and job satisfaction. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2021, 42, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trombetta, J.J.; Rogers, D.P. Communication climate, job satisfaction and organizational commitment: The effects of information adequacy, communication openness and decision participation. Manag. Commun. Q. 1988, 1, 494–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susskind, A.M. Downsizing survivors’ communication networks and reactions: A longitudinal examination of information flow and turnover intentions. Commun. Res. 2007, 34, 156–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cho, J.; Ramgolam, D.I.; Schaefer, K.M.; Sandlin, A.N. The rate and delay in overload: An investigation of communication overload and channel synchronicity on identification and job satisfaction. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 2011, 39, 38–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettit, J.D.; Goris, J.R.; Vaught, B.C. An examination of organizational communication as a moderator of the relationship between job performance and job satisfaction. J. Bus. Commun. 1997, 34, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). Schools: Data on Students, Staff, Schools, Rates and Ratios for Government and Non-Government Schools, for All Australian States and Territories: Reference Period 2020. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/education/schools/2020 (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Hoy, W.K.; Sweetland, S.R. Designing better schools: The meaning and measure of enabling school structures. Educ. Adm. Q. 2001, 37, 296–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nobile, J.; McCormick, J. Organisational communication and iob satisfaction in Australian Catholic primary schools. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2008, 36, 101–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nobile, J. The development of an instrument to measure organisational communication in primary schools. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 3–7 April 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gay, L.R.; Mills, G.E.; Airasian, P. Educational Research: Competencies for Analysis and Applications, 9th ed.; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- De Nobile, J. Development and confirmatory factor analysis of the Organisational Communication in Primary Schools Questionnaire. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modelling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications and Programming, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, R.O.; Hancock, G.R. Best practices in structural equation modelling. In Best Practices in Quantitative Methods; Osborne, J.W., Ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 488–508. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage: Andover, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hutcheson, G.D.; Sofroniou, N. The Multivariate Social Scientist: Introductory Statistics Using Generalized Linear Models; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper, D.; Coughlan, J.; Mullen, M. Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electron. J. Bus. Res. Methods 2008, 6, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indices in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. SEM A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bligh, M.C.; Kohles, J.C.; Pearce, C.L.; Justin, J.E.; Stovall, J.F. When the romance is over: Follower perspectives on aversive leadership. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 2007, 56, 528–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Factor Name (Sample Item) | Number of Items | Eigenvalue | Reliability (Alpha) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vertical openness The principal communicates honestly to staff | 9 | 32.83 | 0.92 |

| Horizontal supportive Staff members at this school support one another | 9 | 8.08 | 0.86 |

| Access There are adequate times to talk to the principal about work issues | 5 | 3.71 | 0.82 |

| Overload I am overloaded with information | 7 | 3.22 | 0.78 |

| Directive The principal tells staff how things are to be done | 5 | 2.46 | 0.73 |

| Downward supportive The principal is encouraging | 4 | 2.32 | 0.87 |

| Upward supportive Staff give moral support to the principal | 3 | 2.20 | 0.76 |

| Democratic The principal asks for input from staff on policy issues | 7 | 2.00 | 0.89 |

| Cultural Staff members show new staff ‘the ropes’ | 6 | 1.75 | 0.79 |

| Adequacy All efforts are made to ensure staff know what is happening | 7 | 1.62 | 0.82 |

| M | SD | SS | MS | df | F | η2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (N = 1547) | |||||||

| Male | 3.97 | 0.70 | 1.621 | 1.621 | 1 | 3.322 | 0.02 |

| Female | 4.06 | 0.70 | |||||

| Age (N = 1549) | |||||||

| 20–30 | 3.94 | 0.71 | 7.857 | 2.619 | 3 | 5.406 ** | 0.01 |

| 31–40 | 4.00 | 0.69 | |||||

| 41–50 | 4.08 | 0.66 | |||||

| 51+ | 4.13 | 0.72 | |||||

| Experience (N = 1548) | |||||||

| 0–5 years | 4.14 | 0.69 | 6.103 | 2.034 | 3 | 4.188 * | 0.01 |

| 6–10 years | 4.02 | 0.68 | |||||

| 11–15 years | 3.96 | 0.70 | |||||

| 16+ years | 4.02 | 0.71 | |||||

| Position (N = 1550) | |||||||

| Teachers | 3.96 | 0.70 | 24.362 | 8.121 | 3 | 17.152 ** | 0.03 |

| Executives | 4.12 | 0.72 | |||||

| Teacher Aides | 4.27 | 0.64 | |||||

| Other | 4.26 | 0.62 |

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. VTOPEN | 3.93 | 0.70 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 2. HZSUPP | 4.01 | 0.52 | 0.34 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 3. ACCESS | 3.85 | 0.74 | 0.75 | 0.31 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 4. OLOAD | 2.25 | 0.64 | −0.58 | −0.26 | −0.51 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 5. DIRCOM | 3.74 | 0.58 | 0.52 | 0.35 | 0.50 | −0.25 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 6. DNSUPP | 3.87 | 0.77 | 0.79 | 0.34 | 0.70 | −0.52 | 0.50 | 1.00 | |||||

| 7. UPSUPP | 3.65 | 0.71 | 0.62 | 0.38 | 0.56 | −0.40 | 0.42 | 0.55 | 1.00 | ||||

| 8. DEMCOM | 3.84 | 0.67 | 0.80 | 0.36 | 0.66 | −0.52 | 0.46 | 0.74 | 0.57 | 1.00 | |||

| 9. CULCOM | 3.67 | 0.63 | 0.43 | 0.57 | 0.44 | −0.30 | 0.48 | 0.44 | 0.43 | 0.41 | 1.00 | ||

| 10. ADEQ | 3.77 | 0.64 | 0.62 | 0.56 | 0.61 | −0.50 | 0.53 | 0.58 | 0.47 | 0.57 | 0.60 | 1.00 | |

| 11. OCGEN | 4.05 | 0.70 | 0.45 | 0.35 | 0.42 | −0.44 | 0.27 | 0.42 | 0.36 | 0.39 | 0.32 | 0.42 | 1.00 |

| Model | χ2/df | p | GFI | CFI | SRMR | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organisational communication | ||||||

| Initial | 4.43 | p < 0.001 | 0.802 | 0.857 | 0.066 | 0.053 |

| Final | 2.68 | p < 0.001 | 0.922 | 0.953 | 0.030 | 0.037 |

| Organisational commitment | ||||||

| Initial | 31.27 | p < 0.001 | 0.949 | 0.925 | 0.087 | 0.158 |

| Final | 1.05 | p < 0.375 | 0.999 | 1.000 | 0.007 | 0.006 |

| Model | χ2/df | p | GFI | AGFI | TLI | CFI | SRMR | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | 2.51 | p < 0.001 | 0.918 | 0.906 | 0.944 | 0.950 | 0.033 | 0.035 |

| Final | 2.69 | p < 0.001 | 0.948 | 0.935 | 0.953 | 0.960 | 0.034 | 0.037 |

| Variables | β | B | S.E. | C.R. | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial model: | |||||||

| OCGENL | ← | Vertical Openness | 0.28 | 0.27 | 0.102 | 2.682 | 0.007 |

| OCGENL | ← | Horizontal Supportive | 0.34 | 0.89 | 0.149 | 5.978 | 0.001 |

| OCGENL | ← | Access | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.034 | 1.460 | 0.144 |

| OCGENL | ← | Overload | −0.19 | −0.32 | 0.070 | −4.588 | 0.001 |

| OCGENL | ← | Directive | −0.16 | −0.17 | 0.106 | −1.596 | 0.111 |

| OCGENL | ← | Downward Supportive | 0.13 | 0.17 | 0.090 | 1.851 | 0.064 |

| OCGENL | ← | Upward Supportive | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.044 | 0.051 | 0.960 |

| OCGENL | ← | Democratic | −0.12 | −0.16 | 0.108 | −1.507 | 0.132 |

| OCGENL | ← | Cultural | −0.09 | −0.16 | 0.097 | −1.650 | 0.099 |

| OCGENL | ← | Adequacy | 0.15 | 0.30 | 0.196 | 1.530 | 0.126 |

| Final model: | |||||||

| OCGENL | ← | Vertical Openness | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.057 | 5.633 | 0.001 |

| OCGENL | ← | Horizontal Supportive | 0.29 | 0.77 | 0.129 | 5.961 | 0.001 |

| OCGENL | ← | Overload | −0.20 | −0.33 | 0.070 | −4.744 | 0.001 |

| OCGENL | ← | Directive | −0.15 | −0.16 | 0.100 | −1.594 | 0.111 |

| OCGENL | ← | Adequacy | 0.13 | 0.19 | 0.142 | 1.313 | 0.189 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

De Nobile, J.; Bilgin, A.A. A Structural Model to Explain Influences of Organisational Communication on the Organisational Commitment of Primary School Staff. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 395. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12060395

De Nobile J, Bilgin AA. A Structural Model to Explain Influences of Organisational Communication on the Organisational Commitment of Primary School Staff. Education Sciences. 2022; 12(6):395. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12060395

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe Nobile, John, and Ayse Aysin Bilgin. 2022. "A Structural Model to Explain Influences of Organisational Communication on the Organisational Commitment of Primary School Staff" Education Sciences 12, no. 6: 395. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12060395

APA StyleDe Nobile, J., & Bilgin, A. A. (2022). A Structural Model to Explain Influences of Organisational Communication on the Organisational Commitment of Primary School Staff. Education Sciences, 12(6), 395. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12060395