Abstract

Faced with the continuous changes that today’s society presents, educational policies place entrepreneurial education and, therefore, the promotion of the entrepreneurial spirit, as the axis on which to articulate effective responses for the current socio-educational context. The need to train students in key aspects that will enable them to face the main difficulties that future labor and social future bring is the focus of attention of the educational environment. In this sense, we set out to find out how entrepreneurial education affects the identity formation of pre-university students in the Spanish context through the pedagogical and environmental factors present in an entrepreneurial education programme. The methodology used is based on qualitative research, which under an interpretative approach, has been assisted by quantitative and evaluative research on educational programmes, in order to try to respond to research objectives. The findings of this research lead us to consider entrepreneurial education in the pre-university environment as effective for the configuration of entrepreneurial identity in students, which facilitates an encouraging future for university students participating in these programmes, who will present an improved entrepreneurial identity that enables them to face forthcoming social, economic and labor reconfigurations.

1. Introduction

At present, and for years, we have been witnessing a capitalist and financial crisis whose figures and data lead us to pessimistic and unflattering conclusions about the future of society. The origin and casuistry surrounding this crisis lead us to the excessive economic rationality that homo economicus has been developing, which has caused an unparalleled social and economic “ailment” [1].

In this new scenario, in which there are no conclusive recipes or ready-made solutions, citizens must act proactively, autonomously, ethically and responsibly [2]. The training and education of future generations require the acquisition of the necessary skills to undertake their own life projects and face the challenges that may undermine personal wellbeing [3].

Since the Lisbon European Council in 2000, we have witnessed a growing interest in promoting entrepreneurial culture and education. The OECD and especially the European Union have recommended that its member states take measures in this area [4]. Thus, in the Spanish context, numerous publications and educational laws have expressed their interest in promoting entrepreneurship as a guarantor of a new economic and social model [5,6,7].

In Spain, the Educational System emerges as an encouraging environment for the promotion of entrepreneurship. With the firm purpose of developing the entrepreneurial spirit, all educational levels have been the target of legislative attention. The LOE [8] (Spanish acronym for Organic Law of Education) was the first Spanish Educational Law that introduced entrepreneurship as a fundamental competence, framed within the Competence in Autonomy and Personal Initiative. Years later, the LOMCE [9] (Spanish acronym for Organic Law for the Improvement in the Quality of Education), with its core competency Sense of Initiative and Entrepreneurship, made it possible for entrepreneurial education to take root in various autonomous communities, and for them to devise proposals of different kinds to strengthen the entrepreneurial spirit among students.

The LOMCE has tried to homogenize proposals and successfully combine the cultivation of personal skills and business orientation. One of the main commitments that this Educational Law has tried to promote is providing a cross-cutting nature to entrepreneurial education within the school curriculum. The current LOMLOE (Spanish acronym for Organic Law for the Modification of the LOE) [10] has achieved the effect in its Article 19 by demanding education professionals to work on entrepreneurship from all areas of knowledge as a pedagogical principle.

On the horizon, there is a latent concern for the promotion of entrepreneurship, and the need to promote and consolidate a new economic model associated with the creation of a business web, an increase in self-employment, and a reduction in youth unemployment [11].

Accordingly, as promulgated by the European Network for Entrepreneurship Education [12], our goal must go beyond the mere promotion of entrepreneurship education. The need to evaluate its impact becomes increasingly necessary [13,14].

1.1. Entrepreneurial Competence

Entrepreneurship and personal initiative are preeminent concepts in today’s society. Entrepreneurship, traditionally oriented towards an economic understanding, is linked to self-employment, entrepreneurship or the creation and development of enterprises.

Although the origins of entrepreneurship are confined to the business and economic sphere, entrepreneurship is a concept that is becoming dynamic, plural and open, gradually allowing it to transcend the boundaries of the economic context and open up a new and valuable range of possibilities linked to it. Increasingly, citizens can act in political, economic, social or cultural spaces with a clear entrepreneurial connotation [15].

When we relate education and entrepreneurship, there is a direct allusion to entrepreneurship education. Entrepreneurship could and should have a place in education, not as business education, but rather as autonomy and a personal initiative [8]. The competence in autonomy and personal initiative, reformulated with the LOMCE [9] in “Sense of initiative and entrepreneurship”, advocates contemplating the business and the personal dimension of students.

In educational practice, education in the competence “Sense of initiative and entrepreneurship” involves attitudinal development and a new mentality that advocates the promotion of entrepreneurship through personal indicators (creativity, leadership and autonomy, and personal initiative), and business knowledge and skills. Thus, with the LOMLOE [10], it is advocated to work on social and business entrepreneurship in all subjects, although in Vocational Training studies, the emphasis is on developing innovation and entrepreneurship skills that favor the professional growth of students. At this educational stage, students should have the necessary skills to create companies and perform entrepreneurial activities and initiatives. It should be noted that Vocational Training in Spain is a post-compulsory level of education, which, like the Baccalaureate, is the prelude to higher education.

1.2. Educational Entrepreneurship and Entrepreneurial Identity

Regarding our research focus, we consider it relevant to approach the construction of the subject’s identity within the framework of the entrepreneurial education that concerns us. It assumes crucial importance in building the subject’s identity, making possible the recognition and use of critical incidences that can be incorporated in their identity baggage after reflection, analysis and debate, which would considerably impact their entrepreneurial identity.

In the economic framework to which this type of education has traditionally moved, the construction of identity appeared decisively linked to business processes. At present, and given that we are facing new social needs, entrepreneurial education must go beyond the traditional acquisition of knowledge and skills linked to the strictly business environment that has developed an entrepreneurial identity in the subject. Therefore, we need to focus on promoting an entrepreneurial culture that leads to the conception of the subject’s identity from a holistic, integrative and global perspective, where the person unites his identity and his business identity into just one entrepreneurial identity [16].

In this regard, there has been a notable increase in policies and plans aimed at promoting entrepreneurship as a fundamental means of fostering social, economic and professional growth [17,18]. Hence, various programs have emerged, whose main purpose is linked to this, although this is not an obstacle to achieving the desired impact on identity. Such programs have different approaches that do not always favorably affect the promotion of entrepreneurship. Thus, we highlight the approaches of education about, in, for and through entrepreneurship as predominant optics in the sector.

Therefore, an entrepreneurial teaching approach that places the student as the main agent and produces an effective connection between entrepreneurial knowledge and behavior [19] is needed. This educational perspective on entrepreneurship facilitates students’ interactive learning, reflection and critical thinking about their own and others’ actions, logical and consistent decision-making, development of agency, and the prioritization and hierarchical organization of actions [20,21]. Certainly, entrepreneurial identity is much more than just knowledge and skills that facilitate entrepreneurial tasks; it requires students to acquire, strengthen and develop a set of personal, organizational and social skills that will give their identity a true entrepreneurial character. That is where “learning to be an entrepreneur” and the educational programs and practices designed for this purpose come into play.

Accordingly, “learning to be an entrepreneur” leads us to the construction of an identity that promotes a “who I want to be” identity in a temporal axis that contains the present, past and future intertwined. In the words of Rae [22] (p. 51), “knowledge, action and meaning are interconnected”, which alludes to an entrepreneurial identity with an integral character structured around the subject’s professional competencies and social and personal skills.

The constitution of the entrepreneurial identity is, undoubtedly, an essential part of the construction of entrepreneurs. Around it, motivational, attitudinal and reflective processes take place, marking the course of entrepreneurial actions exercised by the subject. Despite this, neither the existing literature on the various theories related to entrepreneurship nor the current entrepreneurial education practised have addressed, with sufficient significance, the process of the construction of the entrepreneurial identity in the educational environment or its link with the development and integration of individual skills and knowledge.

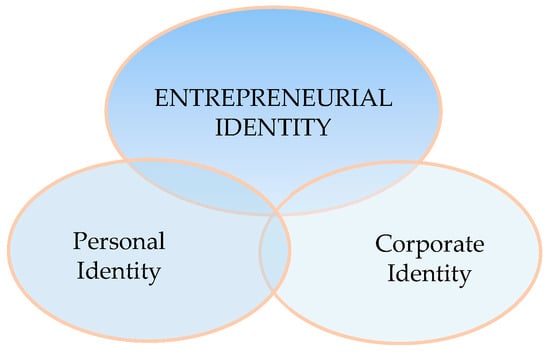

Therefore, we can see that the constitution of the entrepreneurial identity occurs over time, with the historical aspect acquiring a relevant role where the past, present and future assume their identity incidence [23]. Likewise, the entrepreneur identity finds its raison d’être in the interaction and belonging to multiple social groups, where the subject must seek an effective balance between his needs and the cultural and normative designs that circumscribe the aforementioned social groups. At the same time, the forging of identity points to the commitment and influence of others. That vertebrates the collective identity of the group, which would exert a notorious influence on the identity of the entrepreneur, internalizing the processes of negotiation, legitimization and socialization characteristic of the referred collective identity, through the exchange of diverse experiences that find in communication their principal vehicle (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Configuration of the Entrepreneurial Identity. Source: Compiled by authors.

For its part, entrepreneurial education also aims at shaping the subject’s identity. Undoubtedly, the education we are concerned with is based on actions through which students acquire the ability to discern and associate elements that add to their experiential background and, therefore, their identity configuration. In this task, the perceived feedback from the group or groups to which the subject belongs acquires importance since the adoption of reference models constitutes a central point in the forging of the entrepreneur’s identity [24].

Likewise, the evolutionary capacity of the students targeted by entrepreneurial education is the result of the interaction with the context and of the challenges and intentional actions that they take, and that became part of their identity scaffolding. Assuredly, the contextual factor is elemental, as we noticed, in the forging of the subject’s identity. In the educational environment, students begin their journey with an identity that they shape as they acquire personal, professional or psychological competencies resulting from social interaction, and the internal dialogue that the student builds according to his expectations, demands and perceived incidences [25].

The constitution of the entrepreneurial identity is an essential part of the development of entrepreneurial competence, skills and knowledge. This is why an educational approach that considers entrepreneurship from a holistic and integral point of view is needed, leaving behind the traditionalist approach with a more limited scope. Promoting values inherent to the entrepreneurial culture, such as creativity, innovation, responsibility and entrepreneurship at all educational levels, is one of the maxims that current educational policies pursue [26].

In this way, entrepreneurial education programs, which are under an active and participatory education methodology and a reality-oriented approach, impact the construction of the students’ personal and entrepreneurial identities, taking on a leading role.

Therefore arises the necessity to work on contents that can be linked to entrepreneurial identity with education as a facilitating element for the transition of students towards their professional future. Providing society with the necessary dynamism to face the constant changes that are taking place must be one of the essential premises of entrepreneurial culture in all its educational fields [27].

Likewise, it is essential to provide entrepreneurial education with a curricular space that allows reflection and assimilation of its contents and practices, and has a positive impact on the identity configuration of the subject, which will lead to a permanent improvement in the educational model. Students and teachers will join forces to increase the presence of values, initiatives and capabilities of the entrepreneurial culture in society as a whole [28]. To this end, “the curricula of Primary School, Compulsory Secondary Education, Baccalaureate and Professional Training will incorporate objectives, skills, contents and assessment criteria focused on the development and strengthening of entrepreneurship. Also, on the acquisition of skills for the creation and development of diverse business models and the promotion of equal opportunities and respect for the entrepreneur and the businessperson, as well as business ethics” [29] (art. 4). Public administrations, in this case, have an obligation to promote measures for students to participate in activities that allow them to strengthen their entrepreneurial spirit and business initiative, thus fostering attitudes such as creativity, initiative, teamwork, self-confidence and critical sense.

In sum, we can conclude that entrepreneurial identity is the practical compendium between skills and competencies linked to entrepreneurship, the experiences acquired by the subject, the characteristic attitudes of the entrepreneurial potential: creativity, leadership, autonomy, personal initiative and entrepreneurial skills.

1.3. Definition of the Problem and Delimitation of the Research Objectives

Research and education related to entrepreneurship have repeatedly set their objectives at the university level [30,31,32], leaving aside entrepreneurial education, research and training at a younger age despite its relevance as a guarantor of a more promising social future and a prelude to the university stage [33].

The scarcity and topicality of research focused on pre-university entrepreneurship point to the need to delve deeper into its programs (without focusing only on the objectives, competencies, contents or evaluation criteria, but also the methodologies or activities proposed in the classroom), as well as the impact they have on the learner and his identity forging [34,35]. To improve the transversal competencies associated with the employability of budding university students, forging an entrepreneurial identity is considered essential. The more work carried out at pre-university ages on concepts of entrepreneurship, business economic training, business idea and business planning, among others, the better will be the results future university students obtain in terms of employability and entrepreneurship.

In this sense, our research tries to combine both aspects. The purpose is to learn to what extent the pedagogical and environmental factors of an entrepreneurial education program, namely the Arteso Project, affect the configuration of the entrepreneurial identity of adolescents. Therefore, the intention is to understand the meaning and scope that the mentioned program has regarding the entrepreneurial potential of teenagers, framed within the Entrepreneurial Competence.

Noticeably, the Arteso Project (whose name refers to the educational levels in which it is implemented and the field where it is developed: “Art” and “E.S.O”) is an entrepreneurial education program based on the artistic and cultural field. Arteso enhances the personal and professional skills of adolescents through entrepreneurship training in a cross-cutting manner within the curriculum of Compulsory Secondary Education. Such a program enables a practical connection between education and the labor world. This project has been in development since the academic year 2016–2017 at Las Artes School, located in Seville (Spain), as the subject of research for a doctoral thesis [36].

In line with the proposed purpose, we have tried to assess the impact that the Arteso Project has on the essential descriptors of entrepreneurial education: creativity, leadership, autonomy, personal initiative and business skills.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

The research was carried out from the qualitative paradigm, which under an interpretative approach, was assisted by quantitative and evaluative research to respond to the objectives.

Thus, the research method has been mixed and exploratory [37]. Regarding its sequence and priority [38], the qualitative system has been at the core of our research, with quantitative being secondary. The combination strategy achieved the effective integration of both techniques [39].

Considering the complexity of integrating methods of a different nature (quantitative and qualitative) [40], our research model revolves around three evaluative phases (three-phase and multiphase), preceded and succeeded by two informational phases that facilitate the entry and exit of the research field, and whose methodical sequence is governed by the following protocol: qt (quantitative) → QL (qualitative) → qt (quantitative). The validity of the research is carried out through a time triangulation [41] that analyzes the changes produced at the two moments of measurement, pre and post, and an inter-method triangulation combining quantitative and qualitative methods [42].

2.2. Participants

The population of our research corresponds to students in Compulsory Secondary Education, a high percentage of whom will become university students in the future. Participants constituted 61 students from the 2nd and 3rd years of E.S.O (Compulsory Secondary Education). While 49% belonged to the 2nd year, 51% belonged to the 3rd year of E.S.O. Likewise, there was a total balance (50% and 50%) in gender. Regarding age, 48% were 15, 34% were 14, and 18% were 16.

These participants were selected deliberately and intentionally [43], following criteria of accessibility to the field of study and previous knowledge of the informants [44]. In total, they made up 52.14% of the total participating population, comprising a total of 117 pupils.

2.3. Instruments

Quantitative information was collected using the Basic Entrepreneurship Orientation Scale (EOBE acronym in Spanish for Escala de Orientación Básica al Emprendimiento) and the Basic Knowledge and Skills for Entrepreneurship Orientation Scale (ECHEBOE acronym in Spanish for Escala de Conocimientos y Habilidades Básicas para la Orientación al Emprendimiento). The EOBE scale, composed of 23 items and 3 factors (leadership, creativity, and autonomy), aims to determine the self-positioning of students concerning the backbone and fundamental elements of entrepreneurial identity [45]. For its part, the ECHEBOE scale, composed of 25 items and 2 factors (entrepreneurial knowledge and skills), aims to determine the extent to which the program devised within the framework of the research (Arteso Project) has favored the acquisition and consolidation of entrepreneurial knowledge and skills [46]. Both scales have a one to five Likert type of response.

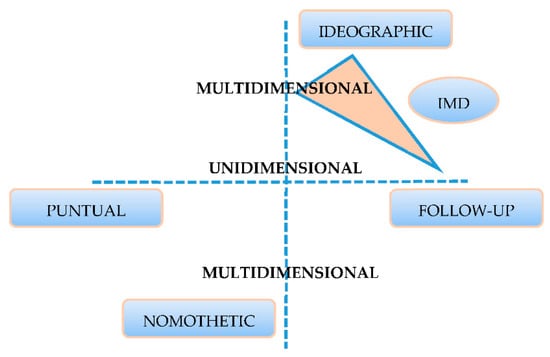

Qualitatively, the techniques of Participant Observation and Structured Interview were used. On the other hand, Participant Observation was materialized in a Field Diary that allowed us to observe the impact that the Arteso Project has on the configuration of the entrepreneurial identity of participating adolescents. In this sense, the observational study design was a follow-up, ideographic and multidimensional (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Ideographic and multidimensional follow-up design. Source: Compiled by authors [47,48].

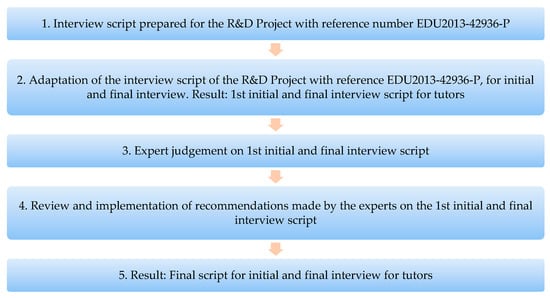

The Structured Interview used was open-ended, non-directed, and carried out with the teachers who were tutors in the courses involved in the program. It was carried out in two moments with four tutors, at the beginning of the program and after its completion, with 42 and 43 questions. The main areas on which the questions were based were entrepreneurial education, teaching and learning processes, and the artistic and cultural entrepreneurship programme. Figure 3 shows the process of elaboration of the interview.

Figure 3.

Process of elaboration of the initial and final interview to tutors. Source: Compiled by authors.

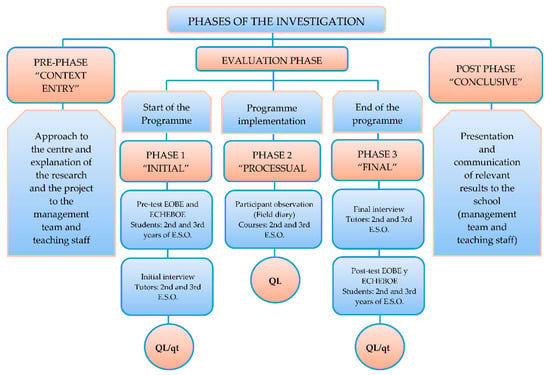

2.4. Procedure

The collection of information was carried out in three phases (Figure 4). The first, called the “initial phase”, corresponded with the start of the program and was aimed at assessing the students’ initial situation with respect to entrepreneurial identity using the EOBE and ECHEBOE scales, as well as the tutors’ perception of entrepreneurial education. The second, “process phase”, referred directly to the implementation and development of the program with the groups under study, assessing its impact on the students as well as the repercussion of different environmental factors. The third and “final phase” took place once the program had been completed. It had the aim of assessing its impact on a set of backbone elements of the entrepreneurial identity (creativity, leadership, autonomy and business skills) by means of self-assessment carried out by students on the EOBE and ECHEBOE scales, as well as the assessment made by the tutors on the program as a whole.

Figure 4.

Table summarizing the phases followed in the investigation. Source: Compiled by authors.

3. Results

The training experience related to the Arteso Project has made diverse and varied contributions to the configuration of the entrepreneurial identity of adolescents. The entrepreneurial identity is constituted by a series of fundamental indicators of entrepreneurial competence. Thus, we can distinguish between personal indicators (leadership, creativity, autonomy, and initiative) and entrepreneurial indicators (entrepreneurial knowledge and skills).

Concerning both indicators, it has been possible to observe a clear impact on the identity configuration of the students targeted by the program, fostering a true entrepreneurial spirit.

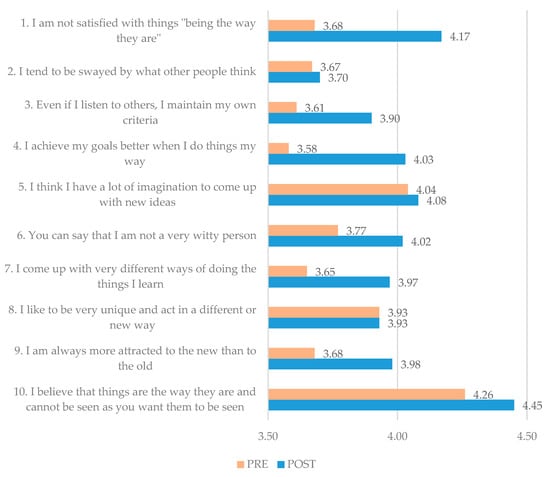

Creativity, a fundamental “tool” for all entrepreneurs, obtained very positive scores on the EOBE scale in Factor 3, which deals with creativity issues. Ideation, inventiveness or innovation have been some elements registering a significant increase among adolescents (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Mean pre (orange) and post (blue) scores of all items that make up Factor 3 (Creativity) of the EOBE scale. Source: Compiled by authors.

Likewise, the analyzed testimonies, both from interviews with tutors and from the field diary prepared by the researcher, show this positive impact on creativity:

Researcher: “Very creative ideas have emerged… this work has encouraged initiative and creativity. Their capacity for ideation has been reflected in the final production.”

The ability to create or design with originality in a novel and unique way is one of the essential pillars that every entrepreneur seeks when producing goods and services [49,50]. With the results obtained on creativity within the framework of our research, we consider that the impact of the Arteso Project has been very positive in the development of attitudes linked to the creative capacity of students.

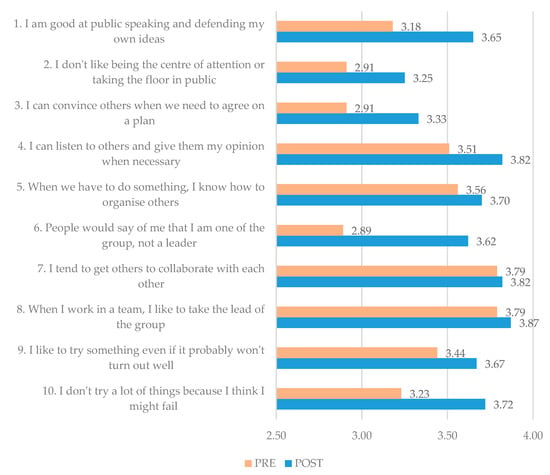

Leadership, for its part, emerges as one of the fundamental pillars of any current educational policy with the overt intention of promoting human and economic development in all spheres [51,52]. Likewise, in the framework of entrepreneurial identity and, therefore, of entrepreneurial competence, leadership assumes a central role that is difficult to replace. For this reason, the Arteso Project has focused on strengthening it and creating situations conducive to its promotion. The results of the EOBE scale, Factor 2 (Leadership), show the positive achievement of this aim (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Mean pre (orange) and post (blue) scores for all items that make up Factor 2 (Leadership) of the EOBE scale. Source: Compiled by authors.

The items related to planning, communication, negotiation, teamwork, decision making or motivation are some of the indicators with a high incidence as a consequence of the implementation of the Arteso Project. Likewise, the tutors, through their testimonies, allude to the important repercussion that the project has had on the students as a whole:

Tutor 1: “All the students have shown a pleasant predisposition to work collaboratively, generating friendships forged in organization, communication and the need to make decisions among all.”

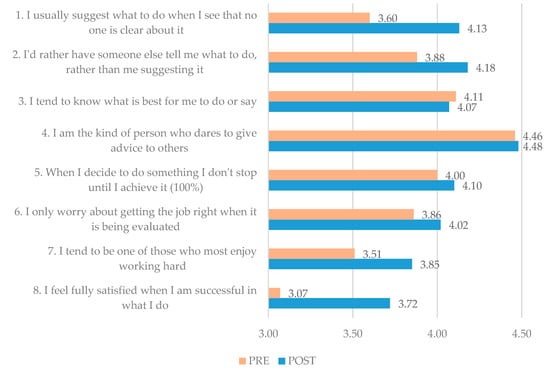

Regarding personal autonomy and initiative, the Education Laws preceded its relevance in the framework of the entrepreneurial identity [8,9], which pointed directly to it as an element consubstantial to the promotion of the entrepreneurial spirit. The new educational essence emerging on the so-called knowledge-based economies, and whose backbone revolved around the link between labor and education, was the focus of attention of all education programs and initiatives aimed at promoting entrepreneurial competence [53].

Within the framework of the Arteso Project, very positive results have been obtained on issues linked to proactivity, risk-taking, initiative, conflict management, etc. (Figure 7). These results point to effective development and impulse on the agential and intentionality of the subject, and the processes of self-regulation and self-evaluation needed for effective promotion of the entrepreneurial identity [54,55].

Figure 7.

Mean pre (orange) and post (blue) scores for all items comprising Factor 1 (Autonomy) of the EOBE scale. Source: Compiled by authors.

Testimonies of the tutors evidenced these beneficial scores for the adolescents:

Tutor 2: “The proactive attitude of all the students, their willingness to resolve issues and embark on a project that we did not know how it would turn out, their willpower and talent have made it possible for Arteso to be so successful.”

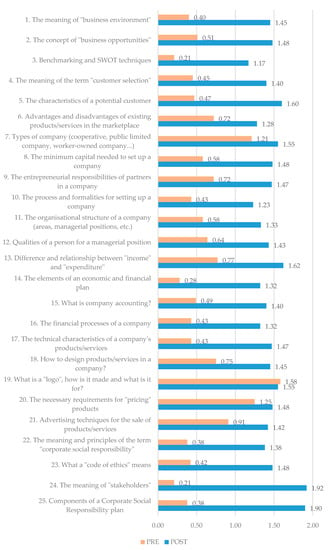

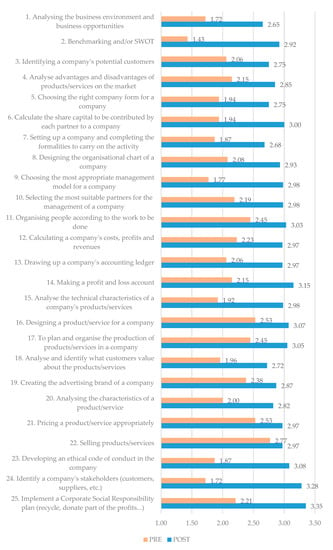

As for the more entrepreneurial side, providing students with appropriate business knowledge and skills to carry out personal and professional projects and goals has been another focus of attention. Recognition of opportunities, critical thinking, sense of responsibility, acquisition of relevant concepts, and practices in the business environment, are some of the main issues in which the Arteso Project has shown high indexes. They have consequently had an impact on students’ identity, as we can see in the results obtained in Factors 1 (Knowledge) and 2 (Skills) of the ECHEBOE scale (Figure 8 and Figure 9, respectively).

Figure 8.

Mean pre (orange) and post (blue) scores of all the items that make up Factor 1 (Knowledge) of the ECHEBOE scale. Source: Compiled by authors.

Figure 9.

Mean pre (orange) and post (blue) scores for all items comprising Factor 2 (Skills) of the ECHEBOE scale. Source: Compiled by authors.

Specifically, in Factor 1 (Knowledge), it is observed that all the items reveal high scores after the implementation of the Project, which determines that it has a positive impact on the acquisition of basic elements, concepts and resources of the business environment. However, item 19 is the only one that already in the pre-test shows a significantly higher score than the rest of the items, meaning that the concept referred to is present in the daily life of the pupils.

In relation to Factor 2 (Skills), it is observed that in all the items there was a notable increment in the acquisition of skills in the business environment after the pupils participated in the project. It was much more significant in items referring to the application of more complex and specific skills with which, a priori, the pupils were not familiar in their application.

Accordingly, we can affirm that the approach of the Arteso Project, its activities, contents, timing, evaluation, etc., has shown its suitability to generate a true entrepreneurial spirit in students.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Today’s society demands the preparation of future generations from a holistic point of view, contemplating the personal and business dimensions together, which will have a decisive impact on the current productive and economic sphere.

The entrepreneurial education programs designed to date focus their attention on business aspects and leave aside the personal viewpoint, which would explain the limited impact they have on the promotion of the entrepreneurial spirit among students. The excess of content focused on business management and the scarce presence of meaningful entrepreneurial skills have been the basis for treating entrepreneurial education programs hastily and from an evaluative point of view.

In response to this, the Arteso Project has tried to focus its objectives on indicators of a personal nature (leadership, creativity, autonomy and initiative) and indicators of a business nature (entrepreneurial knowledge and skills) that have a significant impact on the construction of the adolescent’s entrepreneurial identity. Training in and for entrepreneurship requires the effective integration of both indicators. To achieve the key competency, the sense of initiative, and entrepreneurial spirit, students must acquire knowledge, skills and attitudes that will enable them to act with initiative and creativity in the future, while managing risk and uncertainty in different areas, such as personal, school, social and professional [7]. Through practical and innovative problem solving, as well as the assumption of principles linked to ideation for decision-making, the student will be able to act with initiative and creativity.

The application of Arteso to our participants shows how suitable the program is to develop both indicators, as evidenced by the irrefutable results obtained in the framework of the research.

Despite this, we must ask ourselves how entrepreneurial education programs are made and their objectives. The entrepreneurial culture, its promotion and implementation are still far from desired levels, hence the need to continue working in this area.

Achieving the development of the subject at an intra and interpersonal level, and making possible the opening of new currents of knowledge with the maximum deepening of the personal, social and labor possibilities of subjects must be one of the main objectives of the current entrepreneurial education. In this sense, we are moving decisively towards an entrepreneurial education understood as a humanizing education project whose bastion lies in Entrepreneurial Competence and, consequently, in its linkage around personal goals and plans. This personalization of entrepreneurship would justify its introduction in educational contexts to favor an identity construction in students that stands up to challenges posed by the future.

Delving into diverse research on entrepreneurship can help us achieve long-awaited social and economic change. Likewise, focusing our research on the acquisition and development of transversal competencies linked to entrepreneurship will favor the future employability of students, who will be more qualified in terms of finding employment and dealing with entrepreneurship.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.D.-G., I.P.-N. and L.P.-F.; methodology, M.D.-G. and I.P.-N.; software, L.P.-F.; validation, M.D.-G., I.P.-N. and L.P.-F.; formal analysis, I.P.-N.; investigation, M.D.-G. and I.P.-N.; resources, M.D.-G. and I.P.-N.; data curation, L.P.-F.; writing—original draft preparation, M.D.-G., I.P.-N. and L.P.-F.; writing—review and editing, M.D.-G. and I.P.-N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was reviewed and approved by the Nebrija University Ethics Committee, fulfilling to the regulations agreed upon in the Declaration of Helsinki, granting it the code of approval MDG15022019.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study, through the online platform used to provide the questionnaire.

Data Availability Statement

Information and queries on the data used can be obtained from the authors of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Fayolle, A.; Kyrö, P.; Linan, F. Developing, Shaping and Growing Entrepreneurship, 1st ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd.: Cheltenham, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sproule, J.; Martindale, R.; Wang, J.; Allison, P.; Nash, C.; Gray, S. Investigating the experience of outdoor and adventurous project work in an educational setting using a self-determination framework. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2013, 19, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlile, P.R.; Davidson, S.H.; Freeman, K.W.; Thomas, H.; Venkatraman, N. Reimagining Business Education: Insights and Actions from the Business Education Jam, 1st ed.; Emerald Group Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- González-Tejerina, S.; Vieira, M.-J. La Formación en Emprendimiento en Educación Primaria y Secundaria: Una Revisión Sistemática. Rev. Complut. Educ. 2021, 32, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemany, L.; Álvarez, C.; Planellas, M.; Urbano, D. Libro Blanco de la Iniciativa Emprendedora en España, 1st ed.; Fundación Príncipe de Girona ESADE: Barcelona, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Vega, L.E.S.; González-Morales, O.; García, L.F. Entrepreneurship and adolescents. J. New Approaches Educ. Res. 2016, 5, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ferreyra, H.A. El aprender a emprender como uno de los pilares de la educación del futuro en el marco de la construcción de la calidad educativa. Prax. Pedagógica 2020, 19, 75–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ley Orgánica 2/2006; de 3 de Mayo, de Educación, BOE Núm. 106. Agencia Estatal Boletín Oficial del Estado: Madrid, Spain, 2006.

- Ley Orgánica 8/2013; de 9 de Diciembre, para la Mejora de la Calidad Educativa, BOE Núm. 295. Agencia Estatal Boletín Oficial del Estado: Madrid, Spain, 2013.

- Ley Orgánica 3/2020; de 29 de Diciembre, por la Que se Modifica la Ley Orgánica 2/2006, de 3 de mayo, de Educación, BOE Núm. 340. Agencia Estatal Boletín Oficial del Estado: Madrid, Spain, 2020.

- European Parliament Resolution of 8 September 2015 on Promoting Youth Entrepreneurship through Education and Training; 2015/2006 INI; European Parliament: Brussels, Belgium, 2006.

- Policy Recommendations. Moving Entrepreneurship Education Forward in Europe. Available online: http://ee-hub.eu/component/attachments/?task=download&id=492:EE-HUB-Policy-Recommendations-web (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Moberg, K.; Vestergaard, L.; Fayolle, A.; Redford, D.; Cooney, T.; Singer, S.; Sailer, K.; Filip, D. How to Assess and Evaluate the Influence of Entrepreneurship Education; The Danish Foundation for Entrepreneurship—Young Enterprise: Odence, Denmark, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pizarro, S.C.A. Influencia de la educación emprendedora sobre la intención de emprender del alumnado universitario. Rev. Educ. 2021, 45, 560–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, I.; Guerrero, M.; González-Pernía, J.L. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. Informe GEM España, 1st ed.; Editorial de la Universidad de Cantabria: Santander, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Matlay, H. Entrepreneurship Education: New Perspective on Entrepreneurship Education. Educ. Train. 2018, 60, 923–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollila, S.; Middleton, K.W. The venture creation approach: Integrating entrepreneurial education and incubation at the university. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. Manag. 2011, 13, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berglund, K.; Verduijn, K. Revitalizing Entrepreneurship Education, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gibb, A.A. Entrepreneurship and Small Business Management: Can We Afford to Neglect Them in the Twenty-first Century Business School? Br. J. Manag. 1996, 7, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinonen, J. An entrepreneurial-directed approach to teaching corporate entrepreneurship at university level. Educ. Train. 2007, 49, 310–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnellon, A.; Ollila, S.; Middleton, K.W. Constructing entrepreneurial identity in entrepreneurship education. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2014, 12, 490–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rae, D. Understanding entrepreneurial learning: A question of how? Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2000, 6, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falck, O.; Heblich, S.; Luedemann, E. Identity and entrepreneurship: Do school peers shape entrepreneurial intentions? Small Bus. Econ. 2010, 39, 39–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurczewska, A.; Kyrö, P.; Lagus, K.; Kohonen, O.; Lindh-Knuutila, T. The interplay between cognitive, conative, and affective constructs along the entrepreneurial learning process. Educ. Train. 2018, 60, 891–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amofah, K.; Saladrigues, R. Impact of attitude towards entrepreneurship education and role models on entrepreneurial intention. J. Innov. Entrep. 2022, 11, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loi, M.; Fayolle, A.; van Gelderen, M.; Verzat, C.; Cavarretta, F. Entrepreneurship Education at the Crossroads: Challenging Taken-for-Granted Assumptions and Opening New Perspectives. J. Manag. Inq. 2022, 31, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astiana, M.; Malinda, M.; Nurbasari, A.; Margaretha, M. Entrepreneurship Education Increases Entrepreneurial Intention Among Undergraduate Students. Eur. J. Educ. Res. 2022, 11, 995–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decreto 219/2011; de 28 de Junio, por el que se Aprueba el Plan para el Fomento de la Cultura Emprendedora en el Sistema Educativo Público de Andalucía, BOJA Núm. 137. Junta de Andalucía: Seville, Spain, 2011; pp. 114–216.

- Ley 14/2013; de 27 de Septiembre, de Apoyo a los Emprendedores y su Internacionalización, BOE Núm. 233. Agencia Estatal Boletín Oficial del Estado: Madrid, Spain, 2013.

- Taatila, V.; Down, S. Measuring entrepreneurial orientation of university students. Educ. Train. 2012, 54, 744–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rae, D.; Woodier-Harris, N. International entrepreneurship education. Educ. Train. 2012, 54, 639–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Colombelli, A.; Loccisano, S.; Panelli, A.; Pennisi, O.A.M.; Serraino, F. Entrepreneurship Education: The Effects of Challenge-Based Learning on the Entrepreneurial Mindset of University Students. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Education and Culture Executive Agency; Eurydice; Bourgeois, A.; Zagordo, M.; Antoine, A.; Riiheläinen, J.; Balcon, M.; Noorani, S. Entrepreneurship Education at School in Europe; Eurydice Report; EU Publications Office: Brussels, Belgium, 2018; Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2797/875134 (accessed on 14 November 2021).

- Draycott, M.C.; Rae, D.; Vause, K. The assessment of enterprise education in the secondary education sector. A new approach? Educ. Train. 2011, 53, 673–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guerrero, A.B.; Gutiérrez, A.R.C. Evaluación del potencial emprendedor en escolares. Una investigación longitudinal. Educ. XXI 2017, 20, 73–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Donoso, M. Evaluación de la Educación Emprendedora en la Adolescencia: Incidencia del Programa ÍCARO en la Identidad Emprendedora. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Sevilla, Sevilla, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Heyvaert, M.; Hannes, K.; Maes, B.; Onghena, P. Critical Appraisal of Mixed Methods Studies. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2013, 7, 302–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, D.L. Practical Strategies for Combining Qualitative and Quantitative Methods: Applications to Health Research. Qual. Health Res. 1998, 8, 362–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bericat, E. La Integración de los Métodos Cuantitativos y Cualitativos en la Investigación Social. Significado y Medida, 1st ed.; Ariel Sociología: Barcelona, Spain, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Mayoh, J.; Onwuegbuzie, A.J. Toward a Conceptualization of Mixed Methods Phenomenological Research. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2015, 9, 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Serrano, G.P. Investigación Cualitativa. Retos, Interrogantes y Métodos, 1st ed.; La Muralla: Madrid, Spain, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N.K. The Research Act. A Theoretical Introduction to Sociological Methods, 1st ed.; Aldine: Chicago, IL, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, J.I. Metodología de la Investigación Cualitativa, 5th ed.; Universidad de Deusto: Bilbao, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bernal, A.; Pérez, R.; Rebollo, M.A. Escala de Orientación Básica hacia el Emprendimiento; Proyecto de Investigación EDU2013-42936-P: Educar para Emprender: Evaluando Programas para la Formación de la Identidad Emprendedora en la Educación Obligatoria; Agencia Estatal Boletín Oficial del Estado: Madrid, Spain, 2017; Available online: https://investigacion.us.es/sisius/sis_proyecto.php?idproy=24452 (accessed on 14 November 2021).

- Cárdenas, A.; Donoso, M.; Montoro, E. Escala de Conocimientos y Habilidades Empresariales Básicas para la Orientación Emprendedora; Proyecto de Investigación EDU2013-42936-P: Educar para Emprender: Evaluando Programas para la Formación de la Identidad Emprendedora en la Educación Obligatoria; Agencia Estatal Boletín Oficial del Estado: Madrid, Spain, 2017; Available online: https://investigacion.us.es/sisius/sis_proyecto.php?idproy=24452 (accessed on 14 November 2021).

- Anguera, M.T.; Blanco, A.; Hernández, A.; Losada, J.L. Diseños observacionales: Ajustes y aplicación en psicología del deporte. Cuad. Psicol. Deporte 2011, 11, 63–76. [Google Scholar]

- Ato, M.; López-García, J.J.; Benavente, A. A classification system for research designs in psychology. Ann. Psychol. 2013, 29, 1038–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ferreira, J.L.; Fernandes, C.I.; Matten, V. Entrepreneurship, innovation and competitiveness: What is the connection? Int. J. Bus. Glob. 2017, 18, 73–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parida, V.; Pesämaa, O.; Wincent, J.; Westerberg, M. Network capability, innovativeness, and performance. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2017, 29, 94–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bolivar, A. El liderazgo educativo y su papel en la mejora: Una revisión actual de sus posibilidades y limitaciones. Psicoperspectivas 2010, 9, 9–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sans-Martín, A.; Guàrdia, J.; Triadó-Ivern, X.M. Educational leadership in Europe: A transcultural approach. Rev. Educ. 2016, 371, 78–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, A. The entrepreneurship competence and personal identity. An exploratory research with high school students. Rev. Educ. 2014, 363, 384–411. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Human agency in social cognitive theory. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 1175–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titma, M.; Tuma, N.B.; Roots, A. Adolescent agency and adult economic success in a transitional society. Int. J. Psychol. 2007, 42, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).