Abstract

Soft skills are a crucial component for success in today’s workplace as employers increasingly value work that is collaborative and encompasses diverse perspectives. Despite this, most engineering programs fail to explicitly teach students transferable skills, including the best practices of group work. This research sought to explore how undergraduate experiences of group work change over time. This research also investigated what reflecting on cooperative education (co-op) experiences tells us about teaching group work in academic settings. Despite frequently noting the influence of group work in developing their communication skills and brainstorming ideas over time, students become somewhat more frustrated over time with their experiences of group work, mainly due to conflicting personalities and ideas among team members and/or a “slacker” student. However, our findings also show that students become more confident working in teams over time, as upper-year students were more likely to assume a leadership role and self-reported higher past performance as a group member. This study offers insights into the changing group work experiences of undergraduate engineering students as they progress through coursework and engage in experiential learning and work-integrated learning opportunities, such as co-op placements. The findings of this study can inform educators on how to best incorporate methods for teaching transferable soft skills.

1. Introduction

Emerging literature shows that now, more than ever before, employers value team work, communication, and other ‘soft skills’ over academic ability (i.e., grades) [1,2,3]. Wats and Wats (2009) identified the most essential soft skills as communication, problem-solving, leadership, teamwork, IT skills, and learning to learn skills [4]. In recent practice, post-secondary engineering educators have paid increasing attention to developing students’ soft (social) skills with the explicit purpose of readying future graduates for professional practice [5]. Despite this attention, contemporary research suggests that a soft skills gap continues to exist and that post-secondary education is not yet providing students the soft skills needed to succeed in the workplace [6,7,8]. What then is causing this mismatch of expectations and skill development?

Although the undergraduate engineering curriculum most certainly includes soft skill development, soft skills are often taught as an ‘after thought’ or as less important than technical skill development [9]. This lack of attention does not bode well when the “literature suggests that hard skills contribute to only 15% of one’s success while the remaining 85% is made by soft skills” [4]. Therefore, a question remains as to how engineering instructors can best teach the kinds of soft skills in a manner that could be applied in temporary cooperative education (co-op) settings or for future workplace experiences.

According to Canadian employers, work-integrated learning such as a co-op placement was recognized as one of the best ways for students to learn the hands-on, collaborative practice necessary for the workplace [2]. Yet, the benefits of such learning experiences often depend on the workplace context (including interpersonal relationships) and expectations around the level of accountability and responsibility of a student’s tasks [10]. The study by Crebert et al. (2004) is one of the few that investigates first-hand experiences of soft skill development (what they call ‘generic skills’) from the perspective of employers and recent graduates who participated in a co-op program [11]. Overall, the researchers found that undergraduate curricula had the ability to foster workplace-ready communication skills, problem-solving, and teamwork skills if: (1) undergraduate students were aware of the importance of such skills and abilities at the time of instruction, and (2) if students were given sufficient time and opportunity to practice such skills throughout their degree and in ‘authentic workplace settings’ [11]. The importance of practicing soft skill development throughout an undergraduate career and developing opportunities for ‘authentic workplace’ learning are important lessons for instructors interested in developing undergraduates’ soft and transferrable skills (see also [10]). The authentic workplace learning could occur either through co-op placements or in-class ‘real world’ experiential learning activities (understood critical thinking and problem-solving activities related to actual workplace practices). Nilsson (2010) has also argued that soft skill development should engender the pursuit of lifelong learning and adaptability in a constantly evolving industry, thus answering the call for ‘nimble’ and adaptive graduates [3].

While there are many soft skills identified as beneficial for employee success, Canadian employers have identified “collaboration, teamwork, interpersonal, and relationship-building skills” as the most important ‘soft skills’ for entry-level hires, such as recent university graduates [2]. Research has found that recent graduates felt apprehensive about the lack of attention paid to the best practices of teamwork in their undergraduate education and, consequently, did not feel prepared to work in teams as they entered the workforce [11].

Although collaborative learning, team-based learning, and group work are all different forms of teamwork in pedagogical practice, they require the same set of skills when it comes to teamwork, that is, the ability to effectively communicate, complete tasks with others, and navigate conflict over time. Engineering educators have put quite a lot of time and effort into understanding what kind of setup is required to facilitate effective group work among students. This setup includes, but is not limited to how to form groups, the number of members in a group, the type of assessments associated with tasks and outcomes, the mechanisms to provide peer evaluation and/or feedback, task roles, group norms, team charters, and skills to promote task and team progress [12,13,14,15,16,17].

In order to better understand the student experience of learning about important soft skills such as team and group work, this study explores: (1) how do the undergraduate experiences of group work change over time, before and after co-op experiences, and (2) where do undergraduates learn about group work best practices? This article will shed further light on undergraduates’ perceptions of soft skill development, particularly around group work, which will allow educators to best incorporate methods for explicitly teaching transferable skills, such as group work, and will provide more insight into the opportunities for collaboration among faculty and workplace practitioners. In what follows, the authors provide a brief overview of the literature on the mutual benefit of collaborative work for both students and employers, and an exploration of pedagogical approaches to teaching transferrable skills. Of importance is a recognition of the ways in which undergraduates manage their group work experiences to benefit their task-at-hand, as well as a greater understanding of how these lessons learned might influence their application of team-based skills in the workplace.

2. Teaching Employability—Teaching Group Work?

Regardless of the label they carry—whether it’s ‘employability’, ‘soft’, ‘transferrable’, or ‘human’—soft skills are seen to be lacking in co-op students and recent graduates [8,18,19]. Educators have heard the calls of employers and taken note of the skills surveys calling attention to this gap. Many studies in engineering education literature argue for the inclusion of soft or transferrable skills in undergraduate curricula across all fields of engineering education [20,21,22,23,24]. Yet, it is not just a matter of teaching such skills; recent studies have identified issues facilitating student motivation to learn such skills in practice. Tymon (2013), for example, found that first- and second-year students lacked the motivation to learn so-called employability skills—which would include best practices of team work—while other stakeholders such as final-year students and employers identified their importance [25]. Further, researchers have argued that the lack of success around recent graduates’ preparedness as new hires, that is, their lack of employability, can be attributed to competing learning objectives between co-op employers and educators [10,11], or due to a lack of standardization around how to assess employability (personal) attributes in various contexts [25]. How then must engineering educators teach employability skills in a manner that motivates and facilitates deep-level learning?

Researchers have demonstrated how collaborative learning in classroom settings has several benefits for students. It has been well documented, for example, that when students participate in collaborative learning, they learn the content better through interaction with their peers [26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. Sweeney and Weaven (2005) found that collaborative learning not only facilitates deeper learning, but also develops transferrable social skills that can be used in related contexts such as those skills required for effective teamwork [33]. In a similar outcome, Betta (2016) studied the effectiveness of team-based learning in generic skill development among undergraduates with varied academic backgrounds and found that the majority of students felt that team-based learning: (1) encouraged sharing of different ideas and knowledge, (2) developed new communication skills, (3) generally engaged students, and (4) fostered mutual respect and shared leadership [34]. Furthermore, Chiriac (2014) found that group work also facilitated student knowledge around the underlying dynamics of group behaviour, as well as members’ motivations and group interactions [35]. Chiriac’s research also demonstrated the role of collaborative and group learning to develop group belonging, which in turn—through the development of study groups—facilitated positive academic behaviours such as increased motivation to study. In line with this latter finding, more research is pointing to the role of team-based and collaborative learning to develop undergraduates’ ability to effectively work in groups with diverse team members (see, for example, [36]). The research by Sweeney and Weaven (2005) on group work, for example, demonstrated a greater appreciation for team members of different cultural backgrounds [33].

In this study, the authors conducted research with undergraduate engineering students in various stages of their degree and with various co-op experiences. This research was designed to better understand how undergraduates experience group work, training around transferrable skill development, and perceptions of how their skills ’net out’ in workplace practices. As a result, this study will add to the literature on undergraduate experiences of learning about transferrable skills, such as communication skills and skills related to efficient group work. In what follows, the authors provide an overview of a pilot research study and the implications of their findings for engineering educators.

3. Research Context

The W. Booth School of Engineering Practice and Technology (SEPT) in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, provides a unique degree—a Bachelor of Technology—in which its graduates receive a university degree, a college advanced diploma, and a college business certificate, all within four-and-a-half years. As a practice-oriented engineering program, a quarter of SEPT’s curriculum includes management courses (such as communications courses, finance and accounting courses, operations management, and quality assurance), and a graduation requirement includes the completion of 12 months of co-op placements. The School has also developed feedback mechanisms for employers of recent graduates, a process that has identified the importance of teaching our students the best practices of group work and communication.

In response to this call, first-year Bachelor of Technology (BTech) students participated in nine hours of group work training that featured both didactic and experiential process methods of learning about group work (see [37,38]) over a three-week period. This ‘bolt-on approach’—separate from regular course content (see [21])—functioned with an explicit learning objective to overtly teach students about best practices of group work, was structured in a way that incorporated the hands-on learning of the concepts that students learned within their courses (see [39] for a similar approach). Major topics covered in these workshops included self-reflection exercises around collaborative attitudes and leadership approaches, decision-making tools, the importance of organization (through project planning, such as assigning tasks or roles), and establishing norms around collaboration. Another focus of these workshops included conflict management tools that taught students how to deal with non-contributing teammates or missed deadlines. As further described below, these two issues are typical of teamwork both within the academic environment and in the workplace.

4. Methods

4.1. Study Setting and Participants

For this project, an online questionnaire was administered through LimeSurvey in October 2018 to students in the Bachelor of Technology program at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada (McMaster University Research Ethics Board, MREB-2016-228). The questionnaire was designed by the authors based on the literature regarding group work preferences in engineering pedagogy [35,40]. Participants used a Likert scale to respond to questions such as: participation in the group work workshops affected my ability to ‘de-escalate conflict situations among team members’ and ‘appraise my strengths as a group member’. Participants were also asked: how likely it was that they would implement promising group work strategies in future group work, to assess their perceptions on the usefulness of different tools, and questions that asked respondents to rate past and present performance as group work members. This four-year program is comprised of three streams: Biotechnology, Automation Engineering Technology, and Automotive and Vehicle Engineering Technology. The online survey tool was aimed at students in the second and third years of the program. Due to the relatively large retainment of students from first to second year, it is assumed that the majority of second-year participants in this survey received formal training on the best practices of teamwork through the aforementioned workshops within their first year in the program. Most had yet to complete any formal co-op placement.

Due to recent nature of these group work workshops for first years, the majority of the third-year participants did participate in the group work workshops; however, they had completed some amount of co-op (typically up to four months). In what follows, we categorize data from the online survey into second- and third-year student responses to account for their different experiences around learning about best group work at school or in the workplace (through co-op).

4.2. Data Collection and Analysis

The questionnaires consisted of three parts: Demographic Information, In-Class Group Work Experiences, and Co-op and Workplace Experiences. The questionnaires were available online and remained open for four weeks, during which time participation was advertised to students through announcements made during class and email reminders. The chance to be entered in a draw for one of three $50 gift cards to the campus bookstore was offered as an incentive (the fund was provided by the MacPherson Institute at McMaster University in the form of Leadership in Teaching and Learning Fellowship to ARR and JL). A total of 45 questionnaires were completed by students (45 out of a total of approximately 300 students volunteered to participate in this study). Data was collected through open- and closed-ended survey questions and responses were anonymized and analyzed using open and axial coding techniques that are standard methods for analyzing qualitative research where the goal is to identify major (significant) categories that retain context and meaning for the participants [41]. Responses were anonymized by research assistants and analyzed using grounded theory as a form of inductive coding [42]. Grounded theory is “an analytical method whereby a theory is generated from studying the data using a series of inductive examinations” for the purpose of pulling out/coding new ideas and themes (using open coding methods). Open coding is a method that “assigns codes to every part of the data that seems significant, without yet looking for specific themes or frameworks to apply the data” [43]. The research team then performed axial coding in which the authors looked for “relationships between the codes that were identified during initial coding” [44].

5. Results

Of the 45 completed responses, approximately 56% were completed by second-year students and 44% were completed by third-year students. Response rates were similar across the three specialities: 29% were Automation Engineering Technology students, 38% were in Automotive and Vehicle Engineering Technology, and 33% were Biotechnology students.

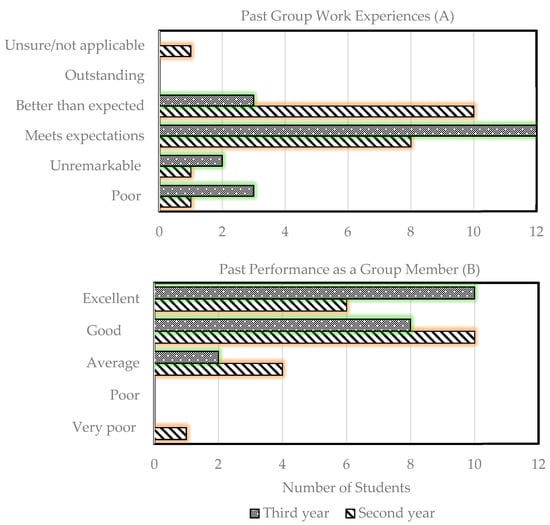

Using a Likert scale question, students were asked to rate their past group work experiences, as well as their past performance as group members. A Likert scale allowed us to assess students’ attitudes and their levels of agreement towards a subject, which could provide more useful information compared to a simple agree/disagree or yes/no question. As depicted in Figure 1, most second-year students felt that their group work experiences were better than expected, while only 15% of third-year students felt the same (Figure 1A). For the majority of third-year students, their experiences only met their expectations. Students were also asked about their past performance as a contributing group member in group work assignments, and over 75% and 90% of second- and third-year students, respectively, felt they performed good and excellent as a group member (Figure 1B), regardless of how they felt about their group work experiences.

Figure 1.

Past experiences of group work (A) and past performance as a group member (B).

The underlying reasons for these discrepancies may be better understood through the qualitative responses. Firstly, when asked to describe the greatest benefit of working in a group, some common themes emerged across the two groups. The most frequently mentioned theme was the sharing of new and different ideas among one another. One third-year student comprised this by stating, “Being able to take in everyone’s ideas because some people will come up with a different or better solution than you would have” (Participant 39). Another common theme was the development of communication and group work skills, which was more frequently reported by second-year students, including one who stated, “Working with a variety of people has broadened my view for a variety of tasks including how to work with people, communicate effectively and reach communal decisions without compromise” (Participant 7). Finally, a shared workload that resulted in time saved was another recurrent theme that was more frequently reported by third-year students.

While only 8% of second-year students described their past group work experiences as poor or unremarkable, a quarter of the third-year students negatively attributed their past experiences with group work. When asked to describe the greatest drawback to collaborating with peers for group work, the most common theme cited by second-year students was the conflict between group members due to different personalities, ideas, or work methods. A second-year student wrote, “In many groups, there will be the leader, the followers and the slacker. Sometimes it can be difficult to work as a group if these three group types cannot come to a conclusion and solution” (Participant 7). Similar sentiments were echoed by third-year students, as shared within one response: “Work habits vary from one person to another so much that, it is easiest to just assume group members are ‘bad’ instead of thinking about school from their unique perspective. The hardest part of group work is maturing as a student and gaining a reality on how people actually work” (Participant 28). However, a more frequent theme that emerged from the third-year students revolved around having a “slacker” (non-contributing) group member, a concept that was also frequently mentioned by the second-year students. By examining the themes that have surfaced from the qualitative responses, it appears that by the time students reach their third year, many of them become frustrated with the uneven roles played by individuals in a group and the accompanying scheduling issues in a demanding program.

When comparing self-reported past performance as a group member of second- and third-year students, the latter group generally rated their performance higher. This is likely due to students becoming more confident/comfortable with their role in a team and the skillsets they have acquired through past group work in their varied co-op experiences and coursework over time (see [45]).

In this study, students were also asked to comment on their overall experience and preference to work with the same group members over a number of projects, courses, or semesters. For the most part, both sets of students stated that they preferred to work with the same group members over the course of a semester (Table 1). This finding was further explored through qualitative responses, which revealed commonalities among the two groups. The greatest factor to explain the ongoing affiliation was familiarity with other students’ work ethic and knowing their strengths and weaknesses. For many students, this leads to a sense of trust and allows them to work well together to achieve a common goal. This was especially emphasized by third-year students, with one stating that “I try to work with the same group of people whenever I have the chance because I trust them. We all excel in different aspects of the program and work well with each other and off each other” (Participant 27). Many second-year students also stressed working with the same group of people due to the social compatibility factor. Getting along well with a set of students means that conflicts are less likely to arise, and when they do, they are easier to resolve. A harmonious group of students are also more compelled to study together, as described by [35] as the study–social function.

Table 1.

Student responses to working with the same group members.

Research has shown that teams made of diverse individuals promote innovation, creativity, and cognitive performance [46]. In this study, some students also touched on the significance of having diverse teams to integrate different backgrounds, experiences, and skills. One third-year student summed this up by saying, “Peers tend to come from different perspectives in life, whether socially or academically, and often bring plenty of unique ideas to the table. You never know what to expect while working with peers, and that is both a blessing and a curse. At least it keeps things entertaining” (Participant 28).

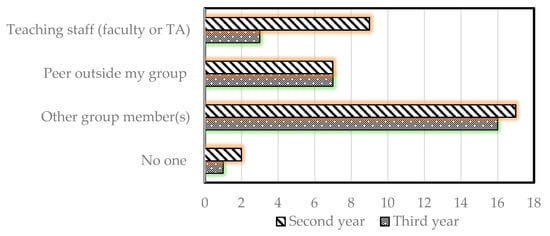

From Figure 2, it is evident that when faced with a challenge in their group work, the majority of students preferred to ask their peers for help, whether these are students inside or outside of their group. This is especially true for third-year students, of which few reported going to a faculty member or teaching assistant for help. Second-year students were much more likely to approach teaching staff to resolve a problem. This difference may be attributed to students’ ability to resolve conflicts independently over time as a result of greater experiences with group work [47]. The same authors also found evidence that this difference may be attributed to the development of other interpersonal skills, such as emotional intelligence, with more group work experiences [47].

Figure 2.

Support resources during team conflict.

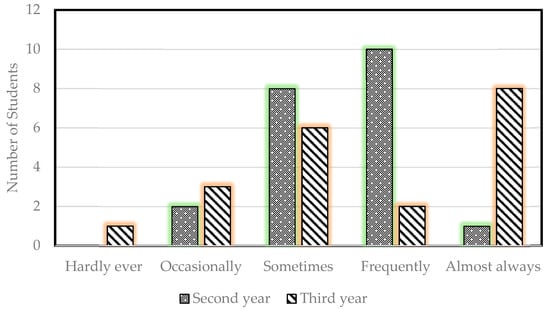

When comparing how often second- and third-year students took the lead on group work assignments, the results were fairly similar (Figure 3). Third-year students were more likely to “almost always” be the leader of the group, while the majority of second-year students reported taking on the role of the leader “sometimes” or “frequently”. Research shows that students who have a great deal of past experiences working in teams will be more likely to undertake a leadership role [48]. Consequently, it follows that upper-year students with greater group work experiences acquired through coursework, co-op placements, part-time jobs, and/or extracurriculars will continue to develop and practice their leadership skills.

Figure 3.

How often students take leadership positions in group work.

According to our survey, 52% of second-year respondents reported having some co-op or workplace experiences compared to all the third-year students, who answered yes. Of those with co-op experience, 75% of third-year students said they would apply their learnings about group work in the workplace to the academic setting.

The students who responded affirmatively to having co-op and/or workplace experiences were also asked to provide examples of good and bad group work experiences. One of the major themes that corresponded to the positive experiences of group work was brainstorming ideas and solutions. For instance, one third-year student shared: “team members would discuss troubles together in group meeting[s] and try to troubleshoot it, together. If you needed more knowledge on a process, team members were willing to share any information they had” (Participant 16). Another theme that was equally prevalent was solving problems as a team, whether this was for customers or other employees. A third-year respondent highlighted the latter, stating, “I had a job as an IT assistant. I had to work along with co-workers to fix their issues on their computers” (Participant 18). Though less common, third-year students also brought up the topic of task division as a worthy experience, particularly when allocating tasks based on differing degrees of skill: “co-worker and I were in charge of making chemical blends. We always agreed upon splitting up the work evenly. He was much more experienced, so sometimes he did a couple of the more difficult blends and I did more of the simpler ones” (Participant 25).

As seen in Table 2, all second-year students felt either competent or highly competent about working in teams within the workplace. While third-year students responded similarly for the most part, a few felt only somewhat competent, perhaps due to a mix of positive and negative group work experiences.

Table 2.

Students’ experiences of co-op and the workplace (n = 33).

Several distinct themes materialized through the responses regarding negative experiences of group work. The most frequently mentioned theme was inferior communication among members of the team, with one second-year student commenting “poor communication between management and other members caused delays, as well confusion between all parties involved” (Participant 2). Two other prominent themes were mentioned equally: slacker group member(s) and working with difficult personalities. A group member who did not carry their weight often led to conflict, as stressed by one second-year student who stated, “sometimes my co-workers did not work, and this led to conflict or me doing their jobs” (Participant 34). The latter was best captured by a third-year respondent who described their experience as “one of the other co-op students got stressed out very easily and would panic about minor projects which made it difficult to work with them” (Participant 20). Interestingly, contrary to task division as a positive experience, uneven task division was also brought up by some third-year students. One wrote, “it made people feel uneasy and disrespected when encountering individuals who cared more about the project being under the individual’s control than the team’s effort to collectively meet a project goal” (Participant 43).

Finally, students also shared their greatest takeaways from group work experiences. Three themes emerged from the responses. Firstly, good communication was the most important lesson learned, particularly among third-year students. One student said, “open communication promotes good and new ideas” (Participant 16), while another stressed that “up front communication and clear goals at the beginning are key” (Participant 29). The second most prevalent theme involved working with diverse personalities and utilizing individuals’ skill sets. This was best exemplified through the following response by a second-year student: “the most valuable lesson for me was learning each other’s strengths and weaknesses. Knowing one another’s personalities is also a huge thing when deciding who works on what with who” (Participant 7). Lastly, a few third-year students also felt that acting in their best interests was more important than group work, with one commenting “Help the team overall but keep the focus on my own tasks and contributions” (Participant 20).

6. Discussion

From our research findings, it becomes apparent that undergraduate students who participated in our survey become somewhat more frustrated over time with their experiences of group work in the academic context. We see this result in the greatest shift down of students’ experiences of past group work performances from ‘better than expected’ to ‘meets expectations’ in one year. This frustration was described by one participant as their experience of ‘maturing’ toward group work: “the hardest part of group work is maturing as a student and gaining a reality on how people actually work” (Participant 28). From our findings, it became apparent that our participants changed how they interacted with group members over time, whether this be through who they chose to turn to in times of difficulty or their level of comfort in taking on leadership roles. As will be further discussed in detail below, quality communication skills are an important investment for engineering educators to make in order to support undergraduates and recent graduates in their teamwork experiences in-class or in the workplace.

When asked about the positive and negative benefits of taking part in group work, student participants positively identified the role of brainstorming and fruitful communication in their experiences. Participants also mentioned issues around their ability to deal with conflict. As discussed by Felder and Brent (2001) [14] and Oakley et al. (2004) [12], teaching undergraduate students specific skills on how to deal with conflict will help them address the most often reported issue in academic group work—‘the slacker’ or ‘social loafer’. Conflict resolution is an important skill to have throughout their education and within the workplace.

As a degree, BTech undergraduates must complete two disciplinary-specific courses around technical and professional communication practices and communication within teams is addressed throughout the group work workshops in students’ first year communications course. The goal of these group work workshops was to teach students team survival skills to be used throughout their undergraduate career and later in the workplace. Scheduling these workshops as a separate training exercise disconnected from any assessment structure was a choice made that aligned with best practices for teaching teamwork for undergraduate engineering students. As argued by Finnegan (2017) [49], group work skills take time to learn. Researchers have argued for various methods to teach group work, including teaching undergraduates about teamwork through either (1) integrated methods, that is, developing students’ teamwork skills in parallel to content knowledge; or (2) bolted-on methods, that is, developing teamwork skills independently to core content [21]. The approach used in this context was to allow BTech students to learn about teamwork by participating in group work workshops in their first semester and by practicing these methods and skills during a semester-long project in the second semester.

The objective of these workshops was to provide students with several tools to use throughout group projects and to give them an opportunity to practice these skills before using them in applied contexts. For example, students were taught how to craft dialogue around the behaviour (of the other member), the consequences (of their actions), and how these made the individual member feel so that students had time to practice this skill in a low-stakes environment. The importance of conflict resolution in students’ group experiences was also apparent from our research findings and can be seen in their willingness to continue working with the same group members, wherever possible, over time due to their cumulative knowledge about their colleagues’ work habits.

This attention to developing best communication practices aligns with our research findings about the importance of communication skills in teamwork. Our finding aligns with Chris Lam’s study as to reasons for social loafing, or ‘the slacker’ effect, described above as a non-contributing group member [17]. The author found that communication skills and task cohesion, which the author defined as “the extent to which a team is united and committed to achieving a particular work task”, influence the presence of social loafing. The author describes five facets of communication: the quality of group discussion (the effectiveness of discussion toward group tasks and goals), the appropriateness (the ability to stay on task during discussions), richness (the attention paid to details during discussions), openness (the receptivity to ideas during discussions), and accuracy (whether discussions were correct and understood). The author argues that communication issues in teams occur when individuals cannot see the value in their individual contributions or in the task at hand, that is, the quality of group discussion, where openness and accurate communication would work to mitigate instances of non-contribution among team members (the slackers or social loafers). Lam argues that instructors should teach high-quality communication skills to mitigate these risks. Due to the significance of communication in this research, the existing literature, and from the perspective of employers for new hires, the role of communication in group work contexts—as described according to Lam’s nuanced understanding—the authors suggest that engineering faculty could incorporate high-quality communication skill instruction into the engineering curricula.

Another source of conflict stems from heterogeneous team members. According to Finnegan (2017) [49] and Summers and Volet (2008) [36], collaborative learning provides opportunities to build undergraduates’ tolerance for diversity among team members. Such lessons would help future Canadian graduates who will be entering an increasingly diverse workforce. While Summers and Volet’s work [36] shows that homogeneous student groups outperform culturally mixed group in the short-term, in the long run, culturally mixed groups performed better and produced more creative and innovative products. This finding aligns with Betta (2016) [34], who found that team-based learning encouraged the sharing of different ideas and knowledge and that this team-based learning developed respect over time; however, and as described by both Finnegan (2017) [49] and Summers and Volet (2008) [36], developing an appreciation for heterogeneous (diverse) group members takes time.

Our findings showed that students sought to work with the same group or team members across projects if possible, and this phenomenon became more evident from second to third year. However, from the qualitative data, it became apparent that students chose familiar group members due to perceptions of social compatibility. From our findings, participants identified ‘knowing how someone works’ as appearing to decrease some of the issues typically experienced when working in groups. This aligns with Jackson’s (2015) [10] findings about the importance of learning how to navigate conflict and manage the expectations of co-workers and managers in work placements. This supports the efforts of BTech’s group work workshops that aimed to overtly teach students various conflict resolution techniques and project management best practices (such as realistic goal setting, role identification, and task and deadline management). It became apparent that more attention should be paid in the engineering curriculum to providing such lessons around teamwork and having students practice these skills during in-class scenarios that reflect ‘real-world’ workplace scenarios (see [21,24]). There appears to be ample opportunity to integrate lessons about the positive outcomes related to heterogeneous group member and innovative, creative group products that would also provide a more ‘real-world’ skill that will be tested in the diverse Canadian workplace.

Despite there being significant attention brought to bolted-on strategies for learning group work in undergraduates’ first year of the program, few respondents identified the group work workshops as a source of learning about group work. Of those who could provide experiences of group work, their responses included topics covered in these sessions; however, it is unclear if these workshops or past work experiences afforded students these insights. To answer the question of how students learn group work skills, the authors will need to conduct further research with participants of their group work workshops.

7. Limitations

As a pilot study to explore undergraduate experiences of group work, this study provides a benchmark understanding of perceptions around team building as a necessary soft skill for current students and recent graduates. Some limitations recognized by the researchers include the small sample sizes used for the survey, where a total of 45 questionnaires were completed by students. Future studies will integrate a longitudinal approach to this work, disseminating questionnaires to the next group of second-year students and following this set of students into their third and fourth years. Future questionnaires will incorporate specific questions around group work workshops from first-year management courses to understand the longevity of the lessons learned through bolted-on teaching strategies. Future studies could also explore how students’ misconceptions and, in some cases, exaggerations about their experiences of group work could lead to a wrong conclusion about group work best practices.

8. Conclusions

This paper explored the pedagogical approaches to teaching transferrable skills and, more specifically, investigated student experiences of group work in co-op and educational contexts. Although the majority of students described their past group work experiences as ‘better than expected’ or ‘meets expectations’, 8% and 25% of second- and third-year students, respectively, reported unsatisfactory group work experiences. The most common drawback when collaborating with peers in scholarly environments was the conflict between group members due to different personalities, ideas, or work methods. It was also found that by the time students reached third year, many of them had already become frustrated with the uneven workload distribution for group projects. Students were also asked about their past performance as a group member where third-year students rated their performance higher than second-year students. Responses from students pointed to students’ increasing levels of confidence and comfort with their role in a group and the skillsets acquired through past group work experiences in academic and co-op settings. Students also unanimously identified that they preferred to work with the same group members over a number of projects and courses because they become familiar with other students’ work ethics, strengths, and weaknesses. This nod to social compatibilities most likely led to an increased sense of trust between group members and mitigated the potential for conflicts to arise. The sense of trust between group members also contributed to the preference of the majority of students to ask their peers for help when faced with a challenge in their group work. Important lessons for future teaching strategies included the development of more workplace scenarios to prepare students for issues of communication and conflict. These scenarios will use diverse workplaces as their context to better prepare the graduates for their next employment experience. The authors also identified that further research is required to understand where and how students learn the best practices of group work, allowing the educators to best incorporate strategies to explicitly teach group work.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L. and A.R.R.; methodology, J.L. and A.R.R.; writing—original draft preparation, J.L., G.S. and A.R.R.; writing—review and editing, M.Z.; funding acquisition, A.R.R. and J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by MacPherson Institute at McMaster University in the form of Leadership in Teaching and Learning Fellowship to A.R.R. and J.L.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Donald, J.; Lachapelle, S.; Sasso, T.; Gonzales-Morales, G.; Augusto, K.; McIsaac, J. On the place of the humanities and social sciences in the engineering curriculum: A Canadian perspective. Glob. J. Eng. Educ. 2017, 19, 6–18. [Google Scholar]

- Business Council of Canada and Morneau Shepell. Navigating Change: 2018 business council skills survey. Bus. Counc. Can. Morneau Shepell 2018. Available online: https://thebusinesscouncil.ca/report/navigating-change-2018-business-council-skills-survey/ (accessed on 8 March 2022).

- Nilsson, S. Enhancing individual employability: The perspective of engineering graduates. Educ. Train. 2010, 52, 540–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wats, R.K.; Wats, M. Developing soft skills in students. Int. J. Learn. Annu. Rev. 2009, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendo-Lázaro, S.; del Barco, B.L.; Felipe-Castaño, E.; Polo-Del-Río, M.-I.; Gallego, D.I. Cooperative team learning and the development of social skills in higher education: The variables involved. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, E.; Strong, D.S. Is engineering education delivering what industry requires. In Proceedings of the Canadian Engineering Education Association (CEEA), St. John’s, NL, Canada, 6–8 June 2011; Queen’s University Library: Kingston, ON, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ferens, K.; Kinsner, W. Industry focus group forum approach for assessing undergraduate engineering program outcomes. In Proceedings of the Canadian Engineering Education Association (CEEA); Queen’s University Library: Kingston, ON, Canada, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Cukier, W.; Hodson, J.; Omar, A. “Soft” Skills Are Hard; A Review of the Literature, Ryerson University. 2015. Available online: https://www.ryerson.ca/diversity/reports/soft-skills-are-hard-a-review-of-the-literature/ (accessed on 8 March 2022).

- Piczak, M.; Heidebrecht, A. Teaching wisdom and other soft skills within engineering curricula. In Proceedings of the Canadian Engineering Education Association (CEEA), Hamilton, ON, Canada, 31 May–3 June 2015; Queen’s University Library: Kingston, ON, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, D. Employability skill development in work-integrated learning: Barriers and best practice. Stud. High. Educ. 2015, 40, 350–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, M.; Bell, B.; Patrick, C.; Cragnolini, V. Developing generic skills at university, during work placement and in employment: Graduates’ perceptions. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2004, 23, 147–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakley, B.; Felder, R.; Brent, R.; Elhajj, I. Turning student groups into effective teams. J. Stud. Cent. Learn. 2004, 2, 9–34. [Google Scholar]

- Oakley, B.A.; Hanna, D.M.; Kuzmyn, Z.; Felder, R.M. Best practices involving teamwork in the classroom: Results from a survey of 6435 engineering student respondents. IEEE Trans. Educ. 2007, 50, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaith, G.; Yaghi, H. Relationships among experience, teacher efficacy, and attitudes toward the implementation of instructional innovation. Teach. Teach. Educ. 1997, 13, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.A.; Sheppard, S.D.; Johnson, D.W.; Johnson, R.T. Pedagogies of engagement: Classroom-Based practices. J. Eng. Educ. 2005, 94, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finelli, C.J.; Bergom, I.; Mesa, V. Student Teams in the Engineering Classroom and Beyond: Setting up Students for Success. CRLT Occasional Paper No. 29. Res. Learn. Teach. 2011. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED573963.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2022).

- Lam, C. The role of communication and cohesion in reducing social loafing in group projects. Bus. Prof. Commun. Q. 2015, 78, 454–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Business Council of Canada. Developing Canada’s Future Workforce: A Survey of Large Private-Sector Employers. 2016. Available online: https://www.bher.ca/sites/default/files/documents/2020-08/Developing-Canadas-Future-Workforce.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2022).

- Simon, B. Skills development in Canada: So much noise, so little action. Can. Counc. Chief Exec. 2013, 6. Available online: https://thebusinesscouncil.ca/ (accessed on 8 March 2022).

- Johnston, S.; McGregor, H. Recognizing and supporting a scholarship of practice: Soft skills are hard! Asia—Pacific J. Coop. Educ. 2005, 6, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Chadha, D.; Nicholls, G. Teaching transferable skills to undergraduate engineering students: Recognising the value of embedded and bolt-on approaches. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2006, 22, 116. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, M.; Tovar, E.; Soto, O. Embedding a core competence curriculum in computing engineering. In Proceedings of the 2008 38th Annual Frontiers in Education Conference, Saratoga Springs, NY, USA, 22–25 October 2008; p. S2E-15. [Google Scholar]

- Capretz, L. Bringing the human factor to software engineering. IEEE Softw. 2014, 31, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, A.; Merle, D.; Jackson, C.; Lannin, J.; Nair, S.S. Professional skills in the engineering curriculum. IEEE Trans. Educ. 2009, 53, 562–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tymon, A. The student perspective on employability. Stud. High. Educ. 2013, 38, 841–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, L. Sharing cognition to construct scientific knowledge in school context: The role of oral and written discourse. Instr. Sci. 1998, 26, 359–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stump, G.S.; Hilpert, J.C.; Husman, J.; Chung, W.-T.; Kim, W. Collaborative learning in engineering students: Gender and achievement. J. Eng. Educ. 2011, 100, 475–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogoslowski, S.; Geng, F.; Gao, Z.; Rajabzadeh, A.R.; Srinivasan, S. Integrated Thinking-A Cross-Disciplinary Project-Based Engineering Education. In Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 1314, pp. 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, S.; Rajabzadeh, A.R.; Centea, D. A project-centric learning strategy in biotechnology. In Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 1134, pp. 830–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabzadeh, A.R.; Mehrtash, M.; Srinivasan, S. Multidisciplinary Problem-Based Learning (MPBL) approach in undergraduate programs. In New Realities, Mobile Systems and Applications. IMCL 2021. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Auer, M.E., Tsiatsos, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 411, pp. 454–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, F.; Srinivasan, S.; Gao, Z.; Bogoslowski, S.; Rajabzadeh, A.R. An Online Approach to Project-Based Learning in Engineering and Technology for Post-secondary Students. In New Realities, Mobile Systems and Applications. IMCL 2021. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Auer, M.E., Tsiatsos, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 411, pp. 627–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabzadeh, A.R.; Long, J.; Couper, R.G.; Cardoso, A.G. Using engineering design software to motivate student learning for math-based material in biotechnology courses. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2020, 36, 878–888. [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney, A.; Weaven, S. Group Learning in Marketing: An Exploratory Qualitative Study of Its Usefulness. In Proceedings of the Australian and New Zealand Marketing Academy Conference, Perth, Australia, 5–7 December 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Betta, M. Self and others in team-based learning: Acquiring teamwork skills for business. J. Educ. Bus. 2016, 91, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiriac, E.H. Group Work as an Incentive for Learning–Students’ Experiences of Group Work. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Summers, M.; Volet, S. Students’ attitudes towards culturally mixed groups on international campuses: Impact of participation in diverse and non-diverse groups. Stud. High. Educ. 2008, 33, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.; Rajabzadeh, A.R.; MacKenzie, A. Teaching teamwork to engineering technology students: The importance of self-reflection and acknowledging diversity in teams. In Proceedings of the Canadian Engineering Education Association (CEEA), Toronto, ON, Canada, 4–7 June 2017; Queen’s University Library: Kingston, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, R. A comparative analysis of different methods of teaching group work. Soc. Work Groups 1996, 19, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, A.; Jobidon, E.; Prier, A.; Khaniyev, T.; Rennick, C.; Al-Hammoud, R.; Hulls, C.; Grove, J.A.; Mohamed, S.; Johnson, S.; et al. Towards a multidisciplinary teamwork training series for undergraduate engineering students: Development and assessment of two first-year workshops. In Proceedings of the ASEE Annual Conference and Exposition, Conference Proceedings, New Orleans, LA, USA, 26 June 2016; Volume 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.; Bristow, M.; Wong, J.C. Emotional intelligence and teamwork skills among undergraduate engineering and nursing students: A pilot study. J. Res. Interprofessional Pract. Educ. 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Given, L. Empowerment Evaluation: The SAGE encyclopedia of qualitative research methods. In The Sage Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods; Sage publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kirner, K.; Mills, J. Writing field notes. In Doing Ethnographic Research: Activities and Exercises; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2020; pp. 105–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargent, S.; Samanta, J.; Yelden, K. A Grounded Theory Analysis of a Focus Group Study. SAGE Res. Methods Cases Health 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, D.R.; Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Mod. Lang. J. 1993, 77, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, J.W. Motivational determinants of risk-taking behavior. Psychol. Rev. 1957, 64, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluut, H.; Curşeu, P.L. The role of diversity of life experiences in fostering collaborative creativity in demographically diverse student groups. Think. Ski. Creat. 2013, 9, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, S.; Faghiharam, B.; Ghasempour, K. Relationship Between Group Learning and Interpersonal Skills With Emphasis on the Role of Mediating Emotional Intelligence Among High School Students. SAGE Open 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colbeck, C.L.; Campbell, S.E.; Bjorklund, S.A. Grouping in the dark: What college students learn from group projects. J. High. Educ. 2000, 71, 60–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnegan, M. Helping Diverse Learners Navigate Group Work (Essay); 2017; Available online: https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2017/08/01/helping-diverse-learners-navigate-group-work-essay (accessed on 8 March 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).