Abstract

(1) Background: Programmatic assessment optimizes the coaching, learning, and decision-making functions of assessment. It utilizes multiple data points, fit for purpose, which on their own guide learning, but taken together form the basis of holistic decision making. While they are agreed on principles, implementation varies according to context. (2) Context: The University of Toronto MD program implemented programmatic assessment as part of a major curriculum renewal. (3) Design and implementation: This paper, structured around best practices in programmatic assessment, describes the implementation of the University of Toronto MD program, one of Canada’s largest. The case study illustrates the components of the programmatic assessment framework, tracking and making sense of data, how academic decisions are made, and how data guide coaching and tailored support and learning plans for learners. (4) Lessons learned: Key implementation lessons are discussed, including the role of context, resources, alignment with curriculum renewal, and the role of faculty development and program evaluation. (5) Conclusions: Large-scale programmatic assessment implementation is resource intensive and requires commitment both initially and on a sustained basis, requiring ongoing improvement and steadfast championing of the cause of optimally leveraging the learning function of assessment.

1. Introduction

Programmatic assessment is an approach to assessment that optimizes both the learning and decision-making functions of assessment. Originally introduced by Van der Vleuten and Schuwirth [1,2], and subsequently described in several papers, summarized elsewhere [3], programmatic assessment utilizes frequent, low-stakes, fit-for-purpose assessments to provide feedback to guide coaching and ongoing learning. Over time, multiple data points, taken together, form a picture of student performance that forms the basis of high-stakes academic decisions, when viewed holistically.

Currently, programmatic assessment is implemented in an increasing number of programs, and research evidence is accumulating around the effects of implementations on teachers, learners, and policies [4]. An Ottawa 2020 consensus panel recently used insights from practice and research to define agreement on the principles for programmatic assessment, which are presented in Table 1 [3].

Table 1.

Ottawa 2020 consensus statement principles of programmatic assessment.

Given programmatic assessment is an approach, not a rigid method, the implementation will necessarily be informed by local context and by the curricular structure, principles, and resources of the program. Understanding diverse implementations affords the opportunity to learn from those experiences, including factors that enable and constrain implementation as well as the varied enactments of the data, decision making, and coaching functions of the model. To that end, this paper will describe the design and implementation of programmatic assessment in the MD program at the University of Toronto.

2. Context

The University of Toronto MD program is a four-year program, one of the oldest and largest in north America. Students enter with a minimum of a bachelor’s degree, with many having completed a master’s or PhD or other professional degree. With approximately 1057 students spread over four years, the program is distributed over 2 campuses and 4 academies, each hosted by 13 affiliated hospitals/networks; there are approximately 3700 teachers in our program. In 2016, the program launched its most substantively renewed curriculum since 1992. This scale of renewal presented the unique opportunity to renew our assessment framework in an aligned fashion, using the programmatic assessment approach. Our previous 72-week preclinical program focused heavily on lecture-based learning and some small group learning to teach basic, clinical, and social sciences as preparation for clinical experiences. Educational activity was centered on courses, which covered basic science knowledge and a longitudinal skills component. Assessments took the form of high-stakes mid- and end-of-course written tests, with skills being assessed using high-stakes objective standardized clinical examinations (OSCEs).

In response to an increasing recognition that traditional medical education models do not fully align with the skills and knowledge required to serve patients and families in today’s societies [5], we undertook a renewal, initially in the pre-clinical curriculum, with a guiding maxim being the purposeful alignment of the curriculum with the requirements of future physicians and society [6]. Our goal, in this newly formed “Foundations curriculum”, is to train medical students who will be: adaptive in response to patients’ needs; able to act in the face of novelty, ambiguity, and complexity; committed to life-long learning; resilient and mindful of their wellness and that of colleagues; and committed to improvement at the individual, team, and system level. We undertook a renewal, which aligned with best evidence and the needs of learners, faculty, and society. The principles of the program renewal included active learning, cognitive integration, and curricular integration; the details of our curriculum renewal are described elsewhere [7]. Our renewal occurred within the broader Canadian context of the widespread movement of competency-based medical education, which, while begun in postgraduate or residency education, set the stage for the need for a similar approach across the continuum.

Concurrent with our instructional changes, our assessment framework was aligned to reinforce the aims of the Foundations curriculum. We adopted programmatic assessment to shift the emphasis from primarily high-stakes decision making, to the function of guiding and informing ongoing learning [8]. Our overall assessment strategy aimed to (a) purposefully align and support the objectives of the curriculum through formative assessment [9], (b) generate meaningful feedback to prepare students for future learning and encourage lifelong learning [10], and (c) provide a more holistic and competency-based picture of student performance.

3. Design and Implementation

Our renewal leadership team was composed of senior program leaders in the domains of curriculum, assessment, faculty development, and program evaluation. From design to implementation, these lenses were employed to ensure we attended to our overarching goals. Education scientists from our local health professions education research center, the Wilson Centre, were embedded in our program leadership, with funded positions, to ensure an evidence-based and aligned approach. Curriculum and assessment decisions were not made in silos, but rather alongside each other. This allowed, from the outset, the design of governance structures and policies that explicitly attended to not only curricular, but programmatic assessment goals, and initiated the blurring of traditional line between the two. Significant resources were invested in project management, from the conceptualization phase, through implementation, and indeed in the maintenance phase. Our program elected to first fully renew our pre-clinical curriculum, newly named Foundations. We since then have implemented many aspects of programmatic assessment in our clinical curriculum, our clerkship, and this work continues now with the substantive renewal of workplace-based assessment.

Overall, the implementation was guided by an emerging and evolving understanding of the principles of programmatic assessment. This understanding was informed by the existing literature, as well as with consultation with experts, such as at Maastricht University and schools that were on the journey of implementing programmatic assessment in similar contexts, such as the University of British Columbia. Our implementation model was to acknowledge firm principles but also to afford flexibility in the practices. We also acknowledged that the curriculum would continue to evolve and iterate and prioritized acceptable and timely options in line with our principles over “perfect” solutions, which would take far longer to implement, if the definition of “perfect” were even known. We recognized that the impetus for a wide-scale curriculum change could lead to misalignment and drift from the central vision for curriculum and assessment. As such, a steering committee and executive leadership team met frequently to review the work of the entire change process. Within this team, we had to negotiate an understanding of the core principles and values of programmatic assessment and to draft a project management charter, which would embody the vision as well as the scope of the work. This proved very useful, as key decision points could be analyzed through the lens of the charter and vision statement. Individuals with expertise such as our education scientists and leaders were called on as needed to help interpret the evidence where the charter and vision statement provided insufficient guidance.

This paper focusses primarily on the implementation within our Foundations curriculum. Below is a description of our implementation, organized under these categories: assessment methods and data; making sense of the data and coaching; decision making and acting on the data; tailored support. For each, the relevant principles from the Ottawa consensus statement for programmatic assessment, outlined in Table 1, are cross-referenced [3].

(A) Assessment methods and data (Table 1; Items 1–6).

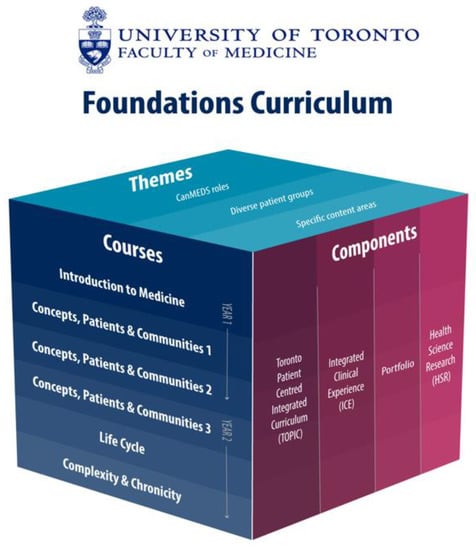

Our curriculum structure, which considered the ability for programmatic assessment to be enacted, is based on a series of consecutive courses. As a spiral and integrated curriculum, each course is the home for basic, clinical, and social sciences related to medicine, scaffolded to build on each other. A curriculum map and competency framework provide a comprehensive picture of how assessments relate to the achievement of the competencies for undergraduate training [11]. Each course is structured around four key components: the Toronto patient-centered integrated curriculum with various modalities, including case-based learning; Integrated Clinical Experience, focusing on clinical skills; Portfolio course, focused on professional development and on guided self-assessment, a key context for our coaching; Health Sciences Research, involving participation in and application of research. Finally, longitudinal competency-related themes, such as professional, leader, and collaborator, as well as diverse patient populations, are integrated across courses. Our curricular structure is illustrated in Figure 1. Because courses are structured consecutively across time, the end of each course of several months provides a juncture for high-stakes decision making. To be successful in a course, one must be judged to be successful in a holistic review of all aspects that occur within that chunk of time. In keeping with programmatic assessment principles, unsatisfactory performance in an individual assessment is used primarily for early flagging of students for attention and support from course leaders (see section C for greater detail). Final high stakes are attached only when considering all of the assessment data points across time within a whole course.

Figure 1.

University of Toronto MD Program Foundations Curriculum.

Our assessment methods were chosen to be fit for purpose, aligned with the curricular goals and objectives, and designed according to best practice. As with most pre-clinical programs, written assessments in the form of multiple-choice questions played a significant role. This renewal was an opportunity to employ computerized testing, which allowed us to apply several tags to all of our questions, according to our own program objectives, Bloom’s taxonomy [12], and blueprint of the Medical Council of Canada, our national licensing body. Other advantages of an online bank related to security, test planning, and ongoing quality improvement. In keeping with best practices, our assessment model also embedded test-enhanced learning (9) in the form of optional weekly formative feedback quizzes. These quizzes helped reinforce taught content by stimulating retrieval practice while allowing learners to gauge knowledge acquisition from week to week. While not mandatory, predictive analytics confirm that students who elect to skip the weekly quizzes are much less likely to meet the end-of-course standards as determined by mastery exercises. These tests implement the repeated longitudinal testing principle and provide a longitudinal picture of competency attainment. This approach promoted knowledge retention and transfer. As such, mastery exercises are delivered every 1–3 weeks, providing feedback to learners on their acquisition of core content and to the program on student progress over the course. Taken together, all mastery exercises within a course are considered in aggregate to assess if the standard is met in the knowledge acquisition and application domain. We implemented a Progress Test, administered four times yearly in the same format and blueprint as the Medical Council Canada Part 1 examination in order to prepare for this ultimate high-stake licensing assessment. Our progress test is currently used in a low-stakes way, being mandatory but used for formative feedback and coaching. That said, our examination of our first four-year cohort revealed that it predicts students in academic difficulty and the Medical Council of Canada exam score. Students are able to track their growth of knowledge as well as self-monitoring and self-regulation necessary to be successful in the licensing exam. Other modalities include written assignments, objective structured clinical examinations, reflections, participation, and professionalism assessments, all of which are low stakes in the feedback moment. Our professionalism assessments are operationalized on the principle that, like all competencies, students are learning and progressing toward becoming medical professionals. This differs from our previous model, which was a “deficit” or lapse-based model of assessment primarily focused on identifying unprofessional students.

All of the aforementioned assessments, in individual instances, are low stakes. However, they are all considered together at the high-stakes decision-making point, which comes at the end of course. Even then, failing to meet a standard, numerical or otherwise, does not in and of itself translate to failing a course, but rather, in the vast majority of cases informs further focused learning and reassessment. Only in instances where the holistic review identifies extensive deficits in multiple areas, and when they are so large as to not credibly be thought to be addressed alongside learning the next part of the curriculum, is a decision made to fail the student and require a full re-take of the course the following year. Further details follow in Section C.

(B) Making sense of the data and coaching (Table 1; Items 2, 10, 11, 12)

We considered it essential that learners, coaches, and decision makers have an electronic portfolio wherein to review longitudinal progress. After examining several existing best practice electronic portfolios from other centers, and on realizing the constraints inherent in having several systems that might not all align with an existing electronic portfolio, we developed our own system known as the University of Toronto MD Program Learner Chart. A user-centric design process was taken to optimize the functions it would serve for various users. After the first year of version one, a formal usability study was employed, leading to various changes for the second version. Our Learner Chart chronicles learner progression through the program, visualizing all assessment data across time and competency, and also includes the contents of progress reviews with coaches and personal learning plans. The coaching role in our program was adopted by an existing tutor role in our Portfolio course, a professional and personal development course with an emphasis on guided reflection. Tutors working with small groups of students had already set a precedent for the development of relationships and trust when reflecting on sensitive content. Thus, the Portfolio course became a natural home for facilitated feedback and dialog on assessment data. As we crafted the new coaching role, we were required to strike a balance with faculty members’ time and availability as a scarce resource. As such, we adopted a model that prompted structured coaching engagement twice yearly with potential for more informal engagement available to students and faculty. Faculty coaches engage in thorough review of all of the data in the Learner Charter followed by a meeting with their students. The meeting is structured to promote a facilitated feedback dialog, and students are expected to document the reflections in a progress review document and personal learning plan. The plan is reviewed and approved by the faculty coach. Organic meetings and mentorship relationships between faculty and students are encouraged and occur on a frequent basis. Given our large number of faculty and students, and a desire to provide a consistent experience, we collaborated with another team to build our faculty development around the R2C2 facilitated feedback framework [13,14]. R2C2 stands for the key components of the framework: build relationship; explore reactions, determine content, coach for change. To our knowledge, this was the first undergraduate MD program to do so. The R2C2 model promotes feedback use and learner agency for development and performance improvement. It uses coaching as a strategy to develop learner engagement, collaborative dialog, and generation of data-driven action plans. Documentation of progress review reflections and personal learning plans, living in the learner chart, provides a focus for ongoing developmental reflection and also serves as humanistic data to triangulate with objective assessment data when holistic, high-stakes decision making occurs.

(C) Decision making and acting on the data (Table 1; Items 7–10)

As our courses progress, we utilize low-stakes mandatory, individual data points, or aggregates of data points within a small time horizon to “flag” students who are at risk of academic difficulty, even if they have not yet formally failed any academic standard. The most notable example is that our written mastery exercises have a standard set for the aggregate of performance across all written assessments in a whole course (e.g., 74% in the first course). The flagging system is used for early identification, such that even if a student is below the aggregate standard on a single mastery exercise at the beginning of a course, there will be an early low-stakes “check-in”. This is an opportunity to dialog about whether there are academic, learning, or intervening personal or health circumstances that would benefit from extra support. We do not wait until the high-stakes decision moment at the end of each course to check-in, coach, and support. The onboarding of students to programmatic assessment emphasizes that these check-ins are intended to support them. The vast majority of students will have at least one check-in over the course of their first year. Students are able to use check-ins as opportunities to access a variety of support relevant to learning difficulties, wellness, and mentorship.

High-stakes decision making, related to status within a course and a year, is the responsibility of our Student Progress Committee (SPC). Prior to our renewal, curriculum directors would present students in difficulty directly to our Board of Examiners, who hold final responsibility for decisions regarding academic outcomes and remediation plans. Our SPC is an intermediary body that was purposefully designed to allow credible, transparent, holistic decision making. Our committee is designed of non-voting members and voting members. Non-voting members include course and curriculum directors, among others; they act as key informants who present data and context on students in difficulty but do not directly vote on the decision. While these were people who traditionally taught, supported, and also made decisions about students, this design helps to separate the feedback and coaching from the decision making. Voting members, many of whom are arm’s length, or even further removed from the MD program, were chosen based on previous experience with high-stakes decision making, and importantly, possess qualitative expertise, including, for example, PhD education researchers. Committee members carefully review the Learner Charts of students in difficulty, and data are then visualized in the meeting in a way that aids holistic review and decision making. Committee members also review students’ personal learning plans and their reflections on their academic difficulties. Outcomes at the end of a course include: satisfactory progress; partial progress (requires a focused learning plan to address unsatisfactory progress in a circumscribed area); unsatisfactory progress (several areas of deficit and unlikely able to address alongside the next course, thus requires repeat the following year). The SPC recommends to the Board of Examiners who has a final holistic review, including consideration of any new data or student perspective on intervening factors for the student in difficulty that may not have been tabled. The Board holds responsibility for the final decision but in the vast majority of cases upholds the recommendation of SPC.

(D) Tailoring of Learning Plans and Support (Table 1; Items 2, 11, 12)

All students are expected to implement their personal learning plans that are approved by their faculty coaches. However, for students who have not met standards, the SPC recommends focused learning plans and reassessments that are tailored to the difficulties, as opposed to a purely numerical approach that would allow reassessment in an area that would tip one of the standards into a pass. The curriculum directors and course directors design and implement the plan and report back to SPC at the following meeting regarding outcomes.

The holistic review of performance at high-stakes junctures by SPC, along with flags earlier in the learner trajectory, provide an opportunity for course directors and the office of health professions student affairs to check-in whether other learning or wellness support would be helpful. There are several such options and those have been augmented over the years since our renewal with our increased emphasis on coaching. After a diagnostic, support can relate to study skills, test taking, content expertise, and, where relevant, formal accommodations for learning difficulties or other issues. After a couple of years of our new program, we began to leverage predictive analytics, based on assessment data, to flag students likely to end up in serious academic difficulty. Based on such patterns, we set parameters for curriculum directors to “check-in” early, much in advance of an academic standard not being met.

4. Lessons Learned

While implementation is context dependent, the following are some key lessons learned from our implementation. Collaboration with other colleagues, both in Canada and abroad, during design and implementation was invaluable for learning and sharing lessons learned along the way.

Timing and planning are everything. Our timing for implementing programmatic assessment coincided with the beginning of a national shift and at the same time as a local commitment to a full renewal of our MD program curriculum, with an early commitment to alignment of curriculum and assessment, with each informing and being built along-side the other. While this was an opportunity, it was also an immense task requiring new skill sets and resources that are not always available to faculty. We were fortunate in that there was a clear mandate from our medical school leadership and commitment of substantial people, financial, and technological resources. We utilized a project management approach to our implementation, an approach that uses timelines and schedules to ensure on-time delivery, while also taking a systematic approach to stakeholder engagement, communications, and anticipation and mitigation of risks to the project. This was an ingredient that was so instrumental to our success that we, after launch, have maintained several staff with formal project management expertise. The scale of our implementation required significant monetary and people resources, not just initially, but on a sustainable basis.

Structural change is necessary for programmatic assessment. Traditional university structures are not always aligned with competency-based decision making or with programmatic assessment principles. For example, making “pass or fail” decisions on the basis of meeting a competency across a series of learning experiences, as opposed to the traditional assessment model based on clinical disciplines, was a relatively new concept for our larger university. We were able to creatively meet administrative requirements by imagining new structures and governance, as we had the opportunity to start fresh from our new Foundations curriculum. New governance, curricular structures, and policies were created to ensure they would enable both not just curricular but programmatic assessment functions. Along with structural change, faculty development was embedded early in the renewal process using a learning-centered faculty development alignment framework [15]. Faculty development leaders were embedded in all design and implementation committees, allowing systematic gathering of data on each anticipated faculty role or task. This informed not only the development of faculty development strategies and resources, but also often informed improvement of curriculum or assessment delivery early on.

Rapid cycle program evaluation is key to understanding whether the impact of our curriculum and assessment changes achieved the intended outcomes. Our renewal provided an opportunity to review and adapt our evaluation and quality improvement processes to ensure rapid and timely changes, where warranted. For example, within written assessments, we developed a process for post hoc review of psychometric properties and student feedback. This process was made consistent so that it was followed by all course directors who are supported with faculty development and just-in-time assessment expertise on item design and quality improvement. The end result was steady improvement in the measurement properties of written assessments and a greater ability to identify areas requiring faculty development or assessment support for courses. This also increased the validity evidence for our assessment program. Overall, our program evaluation evolved to become proactive and quality improvement focused as opposed to retroactive and focused on terminal outcomes. The result was an increased focus of our leadership on the content, process, tools, and outcomes of our assessment framework. We are still evaluating our program against external benchmarks, such as the national licensing exam, for which we were only recently able to get data. The learning processes and impact of programmatic assessment is part of a larger ongoing developmental evaluation of the curriculum reform in our program.

Cultures take time and energy to shift. We intended to implement all of the key aspects of programmatic assessment and did so in a way that could begin shifting culture but still meet broader requirements of our university environment and educational culture in Canada. Most students in our contexts enter medical school with high grade point averages and little experience of low-stakes assessment or of assessments in which they are expected to struggle; there is no doubt an adaptation period is required, as many still see all assessment as high stakes. It has been crucial to dialog with students. In a program with a very active student government, inclusion of students in our committees and communications is essential. When students inquire about or challenge aspects, for example test-taking policies or the role of coaching or why they cannot see the actual questions they got wrong, or how we set standards, we create opportunities to communicate evidence and rationale, and to engage them about how to reach their peers, whether it be in online documents or live town halls. This is important for fostering self-regulated learning and improving buy in.

One key benefit of programmatic assessment is early identification of difficulty, which is sometimes about needing support in adopting new strategies. Students have become very accustomed to the idea that most will be in difficulty in one or more assessments and that “check-ins” by the curriculum directors are meant to be an opportunity for support. As one example of shifting attitudes toward the purpose of assessment, we were surprised when we completed a usability study of our Learner Chart that students wanted the option to toggle the class average on/off, several saying they wanted to use the Learner Chart for its main purpose, tracking and reflecting on their own performance, as opposed to comparing to peers. At the same time, they advocated that the opening page of the Learner Chart should not be scaffolded around competencies but rather that they would rather have a dashboard of assessment activities and the option to drill down to related competencies. This example signaled to us that perhaps they were not being socialized early enough in medical school to the competency framework and shows the importance of examining whether intended changes are experienced by learners as we anticipate.

On the faculty side, our changes occurred concurrently with the competency-based medical education movement in postgraduate education. This is a lot of change that imposes limits on time, both for training and actioning the philosophy. Many faculty were educated in more traditional programs. Regular communication with faculty and an ongoing menu of faculty development options was important. Our faculty development was delivered in various modalities and from just-in-time to ongoing support depending on the need and type of activity.

Less can sometimes be more in curriculum and assessment renewal. Our program committed initially to a full renewal of our pre-clerkship (Foundations) curriculum. We, thus, fully implemented programmatic assessment within that context. Once launched, we initiated a more gradual implementation in the clerkship context, which continues now with a more substantive renewal of workplace-based assessment with a mandate in Canada for all schools to utilize entrustable professional activities (EPAs) as a key assessment unit [16]. EPAs in our context will be yet another source of data in the programmatic assessment framework. We are able to build on strengths and experience from the pre-clerkship for future change. While the introduction of programmatic assessment within Foundations was part of a radical overall curriculum change, the more gradual change in clerkship, not attached to a substantive curriculum renewal, means more of a mix of “old” and “new”, in the short term, which can be difficult for shifting mindsets. That said, fully renewing an entire program at once is a major resource and change challenge that should be undertaken with caution.

Curriculum change is always iterative. As an approach, and one that was meant to shift culture around assessment and feedback in the long term, we had to be willing in the first one to two years to adapt and iterate, showing tangible action based on user feedback. It is crucial to say what you mean and do what you say with regard to change. As an example, our awards committee undertook to review academic awards to ensure criteria and definitions of awards aligned with our assessment philosophy. The traditional definition of the “highest standing” student needed to be revised to ensure it considered not only the highest mark in written assessments but factored in components and themes that are an important part of the holistic judgement of being satisfactory in the program.

Ensuring curriculum and assessment structures were aligned required design and implementation of leadership and committees that attended to both. Communication and change management were key, informed by regular input from all relevant stakeholders as the curriculum was renewed. The embedding of PhD education scientists in curriculum, assessment, and program evaluation ensures we take an evidence-informed and scholarly approach. Continued alignment of curriculum, assessment, faculty development, and program evaluation is not easy to achieve and requires ongoing maintenance [7].

5. Conclusions

Programmatic assessment implementation in our MD program benefited from timing, local and national context, and augmentation of resources in the area of student assessment. Our implementation addressed the recommendations of best practice and the core principles from the Consensus statement [3]. While a radical change undertaken as part of a full curriculum renewal, it is not one and done. Rather, it requires a sustained commitment to the principles and an openness to adapt and evolve practices according to research and program evaluation data, and importantly, the voices of our students and teachers. While we continue to hone this approach within undergraduate medical education, our colleagues in postgraduate education do the same, with different constraints. Culture is shifting across the continuum in our context, where skeptics gradually are coming on board, seeing the undeniable benefits of leveraging assessment for learning. Namely, our program utilizes data day to day for feedback and tailored coaching, and over time for forming a rich, holistic picture of each learner on which decisions can be made and supports put in place. It helps that our faculty are being asked to engage in similar tasks across the learner continuum. As several years of learners are now progressing through the learning continuum locally and beyond, they will become the teachers and continue to employ this approach. We are already seeing the benefits of this approach in that more students are receiving coaching and support; we are able to better track student progress and to implement high-quality assessment practices that better prepare students for future learning. We hope this translates in the long term to health care providers who see feedback as crucial to ongoing improvement and that this impacts the patients and systems we serve. Much scholarship must be conducted to answer these questions on broader societal and health system impacts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.R.T. and K.M.K.; Methodology, G.R.T. and K.M.K.; Project administration, G.R.T.; Writing—original draft, G.R.T.; Writing—review and editing, K.M.K. and G.R.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The innovations described were funded by the University of Toronto Temerty Faculty of Medicine as part of a curriculum renewal.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The implementation described in this paper is the result of the work of too many people to name. Katina Tzanetos led the development and assessment of written assessment approaches. Jana Lazor led the Faculty Development team. Richard Pittini collaborated on the visioning and implementation. David Rojas has been crucial in his leading the program evaluation processes. Nirit Bernhard’s leadership of the Portfolio course was essential to the enactment of coaching. Several team members in our Office of Student Assessment and Program Evaluation have been invaluable to the initial and maintenance phases. Cees van der Vleuten was generous with his expertise along our trajectory of implementation. The implementation would not have been possible without the collaboration of Marcus Law who led the curricular renewal and was committed to alignment with assessment. Patricia Houston’s leadership and steadfast commitment to creating the best program possible for our learners and society was pivotal to our success.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Van Der Vleuten, C.; Schuwirth, L.; Driessen, E.; Dijkstra, J.; Tigelaar, D.; Baartman, L.; Van Tartwijk, J. A model for programmatic assessment fit for purpose. Med. Teach. 2012, 34, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Vleuten, C.; Schuwirth, L. Assessing professional competence: From methods to programmes. Med. Educ. 2005, 39, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heeneman, S.; de Jong, L.H.; Dawson, L.J.; Wilkinson, T.J.; Ryan, A.; Tait, G.R.; Rice, N.; Torre, D.; Freeman, A.; van der Vleuten, C.P. Ottawa 2020 consensus statement for programmatic assessment-1. Agreement on the principles. Med. Teach. 2021, 43, 1139–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schut, S.; Maggio, L.; Heeneman, S.; Van Tartwijk, J.; van der Vleuten, C.; Driessen, E. Where the rubber meets the road—An integrative review of programmatic assessment in health care professions education. Perspect. Med. Educ. 2021, 10, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asch, D.A.; Weinstein, D.F. Innovation in medical education. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 794–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucey, C.R. Medical education: Part of the problem and part of the solution. JAMA Intern. Med. 2013, 173, 1639–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulasegaram, K.; Mylopoulos, M.; Tonin, P.; Bernstein, S.; Bryden, P.; Law, M.; Lazor, J.; Pittini, R.; Sockalingam, S.; Tait, G.R.; et al. The alignment imperative in curriculum renewal. Med. Teach. 2018, 40, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuwirth, L.; van der Vleuten, C. Programmatic assessment: From assessment of learning to assessment for learning. Med. Teach. 2011, 33, 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulasegaram, K.; Rangachari, P.K. Beyond “formative”: Assessments to enrich student learning. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 2018, 42, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Heeneman, S.; Oudkerk Pool, A.; Schuwirth, L.W.T.; van der Vleuten, C.P.M.; Driessen, E.W. The impact of programmatic assessment on student learning: Theory versus practice. Med. Educ. 2015, 49, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MD Program Education Goals and Competency Framework. Available online: https://md.utoronto.ca/education-goals-and-competency-framework (accessed on 25 January 2022).

- Bloom, B.S. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, Handbook I: The Cognitive Domain; David McKay Co. Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Sargeant, J.; Lockyer, J.; Mann, K.; Holmboe, E.; Silver, S.; Armson, H.; Driessen, E.R.; MacLeod, T.; Yen, W.; Ross, K.; et al. Facilitated reflective performance feedback: Developing an evidence- and theory-based model that builds relationship, explores reactions and content, and coaches for performance change (R2C2). Acad. Med. 2015, 90, 1698–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Armson, H.; Lockyer, J.M.; Zetkulic, M.G.; Könings, K.D.; Sargeant, J. Identifying coaching skills to improve feedback use in postgraduate medical education. Med. Educ. 2019, 53, 477–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bajcar (Lazor), J.; Boyd, C. Creating a new pedagody for Faculty Development in Medical Education. In Eposter Proceedings; Association for Medical Education in Europe: Milan, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ten Cate, O. Nuts and bolt of entrustable professional activities. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2013, 5, 157–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).