Abstract

The objective of this study was to analyse nursing students’ motivation to choose the midwifery career. This is a cross-sectional study with a qualitatively driven mixed-methods approach. The settings are three higher education institutions located in Portugal. The study was conducted between September 2019 and November 2021, with the participation of 74 midwifery master’s students, through convenience sampling. The data were collected through the LimeSurvey software and were subsequently analysed in the SPSS and IRaMuTeQ software programs. The emerging thematic areas were as follows: (1) building a professional identity and (2) knowledge construction. From these two thematic areas, six classes emerged that revealed commitment to the profession. It is in Class 6 that the ancestral essence of the profession lies, revealing the meanings of competence and care perpetuation linked to gender. Midwifery is a first-line profession, and the career choice reflects a commitment to support the mother/newborn dyad in view of the inevitability of human care for the preservation of the species. Midwives with a Socratic inspiration are the model for the profession. Given the development of professional identity, it can be interesting to have an educational curriculum where human values are reinforced. A woman-centred birth environment and birth territory are elementary for midwifery education.

1. Introduction

A profession, or an area of professional specialization, conveys stereotypes which generate performance expectations for those who choose the career. Choosing a profession, foreseeing devotion to a given knowledge area, requires personal resolution. It constitutes a relevant phase, as it anticipates the activity that will fill a large part of person’s life. Career choice initiates the design of the professional self-concept, as well as the idealization and construction of the proficiency traits, perhaps influenced by culture, personal characteristics, previous experiences, or models [1,2].

Motivation consists in persuasion and enthusiasm to achieve a given objective [3,4], generating deliberate and goal-directed thoughts and behaviours [5]. Whether the difficulties are known or surprising, if motivation is strong, there will be perseverance in the face of obstacles. Equipped with their own beliefs, with high persistence, the individuals will orient themselves in the direction that they determined, namely in the choice of the profession [6]. The preferences for choosing a career in health often refer to prestige, but also to the altruism of serving/assisting/supporting others [3,7,8].

Motivation for the midwifery profession requires personal and emotional investment in a path towards self-definition of the professional profile or identity [3,9]. In the training of midwives, the learning process has concrete evidence, as the international standards determine it, both for the roles of the students and of the institution that trains them [10,11]. Even in countries or societies with high health needs and low economic compensation, being a midwife is a source of pride and provides a strong professional conscience. For these midwives, offering women the best care possible in the pregnancy-puerperal cycle is a personal and professional gain [12]. The professionals’ awareness regarding their role and performance in periods of significant human vulnerability contains benefits for professional self-image [13], perhaps motivating for the career. Midwives take pride in their profession in the different performance contexts [3,14], and their relevant role in health is widely recognized [15,16]. Midwives’ activity preserves the continuation of the human species through essential care. It is on this essence that the students’ training is based, although the current modalities present different paths to achieve training.

The principles of Bologna in professional midwifery education have been realised throughout Europe. The pillars of training were identified through Directive 2005/36/EC and the Munich Declaration. The standard for Europe was defined and the qualifications to be achieved by potential professionals were identified, that is, by students who wish to become midwives. However, in the European Union(EU), although the vocational/professional model is giving way to a graduate/academic teaching model [16,17], there are differences such as the proportion of theoretical versus practical hours [18] or in more conflicting aspects such as the academic undergraduate level versus graduate or master’s studies [19]. There are also differences even in terms of duration and access, as we can see in the United Kingdom or Malta, where midwives’ education lasts three years, or in Croatia, where access to the course is possible after finishing high school (8 years of basic schooling) [20]. In fact, as an example, although some studies indicate a master’s academic level in Portugal and Spain [21], this is not absolutely true. On the other hand, although European countries are governed by the same Community Directive on midwife training (Directive 2005/36/EC), professional activities do not exactly coincide. In France, Sages-Femmes are recognized as competent to prescribe certain medications (haemostatics, local anaesthetics) and auxiliary diagnostic tests (radiography, ultrasound) [22]. In Portugal and Spain it is necessary to have completed initial training in nursing to be a midwife, while in others, this has a pejorative implication, as the absence of legal emancipation between nursing and obstetrics is questionable [20].

Given that Portuguese nursing schools currently receive national students and that most of the foreign students are from Spain, we will focus our attention mainly on an Iberian vision of motivation for the profession of midwifery. Perhaps this study, considering the intrinsic process of motivation and the context of educational development, can provide a contribution to the literature, offering a portrait of why Portuguese and Spanish students choose to be midwives.

The study of motivation for the profession is interesting, from a perspective of care quality, that is, of the relationship that the care providers (midwives) have with their area of expertise. In fact, midwives deal with the woman’s and the couple’s emotionally significant moments every day. Moments of happiness, but also of stress. The current research can bring about contributions to the critical reflection of training in order to implement adjustments in the curricula. In fact, although there is a regulatory body for education, the perspective of students, as recipients of the syllabus and course requirements, may reflect unidentified gaps in the curricula and thus identifying these gaps may help improve the teaching paradigm.

Therefore, the research question for the current study is as follows: What are the underlying reasons for choosing the midwifery course in nursing students? The objective of this study was to analyse nursing students’ motivation to choose the midwifery career.

1.1. Midwives’ Education in Portugal and Spain

In Portugal, access to training that enables midwifery education is reached after an 18-year training path. In other words, in sequence, 12 years of basic schooling are necessary [23], as well as four years of 1st cycle nursing training. In addition, for the Portuguese candidates, the Ordem dos Enfermeiros (OE) requires effective clinical practice as a general care nurse for a minimum of two years. After this path, the interested person can apply, on their own initiative, to a university or higher education institution (HEI), submitting his/her curriculum. In these universities or HEIs, the candidate’s curriculum is evaluated and scored, determining admission or denial of admission according to the number of vacancies defined by the academic institution. Successful completion of the two-year training program grants the candidate an academic degree, a master’s degree, that is, the academic qualification of the second cycle.

In Spain, access to training in the area designated as obstetrics-gynaecology nursing (midwifery) begins with a 12-year course of basic education and a “degree” in nursing [23]. Application then requires the nursing graduate to sit for a state exam, which takes place annually in each autonomous community, for admission to the specialization. The call for the exam calendar is published in the Boletín Oficial del Estado (BOE). With the entry into force of Law 44/2003 on November 21st, each Midwife Teaching Unit from each autonomous region defines the number of vacancies for general nurses who wish to carry out the obstetric-gynaecological nursing specialization; that is, each hospital that is accredited to receive obstetric specialty students annually defines the number of vacancies [24]. In this way, the nurses who sit for the state exam are admitted to the training program only if the teaching unit of the hospital institution opens vacancies. It is not possible to apply directly to the teaching unit, as is the case with applications for master’s degrees in universities. With success, the nurse enters a training model, called “Resident Internal Nurse” (Enfermeiro Interno Residente, EIR), through a written contract (Royal Decree 1146/2006). Signature of the contract on an annual basis between the student and the teaching unit requires that the student be healthy and able to show proof of a previous medical examination. In this contract, the mentor or preceptor who assists the student’s entire development is designated. During the specialty training period, a salary is given to the student, which is the base salary in amount. They are not allowed to work and study at the same time.

To demonstrate the similarities in the training between the Iberian countries, Table 1 presents a summary of the training topics in Portugal and Spain.

Table 1.

Training topics in Portugal and Spain.

1.2. Midwives’ Professional Practice in Portugal and Spain

Midwives’ Legis Artis brings together a set of rules and principles whose fundamental purpose is to help in the perpetuation of the species. Keeping in mind the principle of “obligate midwifery” imposed by bipedalism [25,26], midwives are responsible for and carry out concrete care for women in clinical practice, applying the knowledge that the state of science allows.

In Portugal, the professional practice is regulated by the Ordem dos Enfermeiros (OE), a professional organization governed by public law (Law No. 156/2015 of 16 September), recognized by the Portuguese Constitution and regulated by laws common to all professional associations (Law No. 2/2013, of 10 January). It is an autonomous and independent body that regulates the profession, with no possibility of being mistaken for a union organization. The functions of the OE include defence of the citizens’ rights to good quality assistance and safeguarding human interests. Simultaneously, the OE has technical authority over the knowledge area, with the function of defining professional competencies and professionally accrediting the nurses who work in the country (Article 3(2)). In other words, the OE defines the competencies that nurses specializing in maternal health nursing must acquire in training.

In Spain, the midwife profession is regulated by European law according to competencies. Midwives are understood as autonomous professionals who work within the scope of primary care and differentiated care. The field of coverage includes reproductive health, sexuality, and climacteric health. The Spanish regulations recognize that the scope of practice extends to assistance, management, teaching, and research. Midwives contribute to research and publish new knowledge in midwifery care [27], which is constantly evolving as an evidence-based practice [28]. Completion of the EIR is a way to access the PhD degree. Table 2 presents some characteristics of professional midwifery practice in Portugal and Spain.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the professional midwifery practice in Portugal and Spain.

In summary, although they have the same community orientation as their starting point, the EESMO and midwife training courses follow different paths [29]. In Portugal, training has a more academic and theoretical focus. In both countries, although with different numbers, the clinical experiences focus on the reproductive cycle, sexuality, pre- and post-reproductive gynaecology, and the pre-conception and climacteric phases.

As far as it was possible to discover, in Portugal there are no studies that have reported on the motivation to become a midwife. Looking toward hard statistics, it is a country where 1567 midwives work in hospitals, with a ratio of 24.49/100,000 inhabitants (Statistics National Institute, Portugal in 2020), a figure that is lower than the European mean of 39.99/100,000 inhabitants [30]. It is also a country where the main obstacles to professional development are as follows: medicalized care models, lack of financial resources in institutions, and a care culture without clarification of the professional roles [31].

2. Materials and Methods

This is an exploratory and cross-sectional study with a qualitatively driven mixed-methods research approach based on content analysis of written narratives. The study has a descriptive methodology, centred on the perspective of Portuguese midwifery students.

2.1. Setting and Participants

A convenience sample was used consisting of 74 student nurses attending the Midwifery Master’s Program (MMP) in state higher education institutions, located in Territorial Unit II, Alentejo, Portugal. The sample includes conditions for a variety of experiences related to the phenomenon of interest [32]. The following inclusion criteria were defined: (a) originating from Iberian or Portuguese-speaking countries (Países de Língua Oficial Portuguesa, PALOP); (b) written expression in Portuguese or Spanish; (c) professional title of nurse; (d) attending the MMP for the first time; and (e) being a student at the institution. The exclusion criteria were: (a) participating in a national or international inter-university exchange program; (b) having a 2nd cycle qualification in the same area, in a Portuguese or foreign university; and (c) previous failure in the course.

2.2. Data Collection

Data collection took place in three consecutive academic years (2019–2020, 2020–2021, and 2021–2022). The instrument, incorporated in the LimeSurvey software, was emailed to the student nurses who attended the MMP. In the data collection instrument elaborated by two of the authors (M.S.-S., H.D.) with the approval of the others, the first section introduced sociodemographic variables (nationality, age, gender, marital status, and number of children). The second section asked for aspects related to nationality and place of origin. In the third section, a written answer to the following prompt was asked for: In a deep reflection and in a mature analysis, talk about the reasons that led you to want to attend the course that gives you the certifications to become a midwife. In a note, the participants were asked to answer the questionnaire without interruption and in a quiet place.

The instrument was always sent by the only author who had access to the participants’ identification data (M.S.-S.) at the beginning of each academic year. Thus, in September 2019, 2020, and 2021, a total of 95 potential participants received the instrument through email messages. The mean time for filling it out was 20 min, confirmed by observing the start and end times in the LimeSurvey software. Choice of the place to answer the instrument was at each participant’s discretion, as access by email allowed them to manage the place and opportunity to respond. Seventy-five student nurses submitted their answers, forwarding them to the professor who directed them to the link for the LimeSurvey software (M.S.-S.). One questionnaire was rejected because nearly half of the questions were not answered. The unanswered questions referred to the socio-family and academic variables (gender, age, place of origin, and academic institution); the question that asked for their reflection on the choice of the course had also been left unanswered. All the data were collected at the end of November each year. The return rate was 77.9%. Given the questions’ simple nature, no pilot test was performed.

2.3. Ethical Considerations

Permission to begin the research was obtained from the hierarchical representatives to approach the students in the three academic institutions. The study was publicized in the classroom and the students had been previously invited to participate by one of the professors from each academic institution (M.S.-S., A.S. and H.D.). Subsequently, contact was made via email, where the formal invitation to participate was presented. The message stated the study’s objective, informed the students about the method, and guaranteed confidentiality and anonymity of the answers. The data collection instrument included the following sentence in the first field: I am responsible for my actions and for the full use of my faculties, and I confirm that I will answer this questionnaire of my own free will and allow the use of my data by marking “yes”. Progress was only allowed after the participant marked “yes”. In-person signature collection was not conducted for this research; it was considered that answering the questionnaire meant tacit consent to participate [33]. Access to the answers in the LimeSurvey software was allowed only to one of the authors (M.S.-S.), who anonymized them before the analysis.

2.4. Data Analysis and Use of the SPSS and IRaMuTeQ Software Programs

The quantitative data were analysed using the IBM SPSS® (Statistical Product and Service Solutions) software, version 24. The narratives underwent lexicometric analysis using the IRaMuTeQ (Interface de R pour les Analyses Multidimensionnelles de Textes et de Questionnaires) software, version 0.7 alpha 2.

The data were exported from the LimeSurvey file to the SPSS matrix. The matrix was reviewed and recoding was performed in categories of some variables (age vs. age groups) and for the workplace (for dichotomous variables: hospital/community). The quantitative variables were subjected to descriptive statistical analysis. The text of the narratives, collected in LimeSurvey, was subjected to spelling correction. Three authors with previous experience performed this analysis (M.S.-S., A.S. and H.D.).

The qualitative data were subjected to several stages. Phase 1: full reading of each participant’s narrative. No case was rejected, as all the answers suggested that they were experiences with potential for analysis. Phase 2: repeated reading of the narratives and constitution of the analysis corpus. Phase 3: corpus organization, according to the analysis protocol of the IRaMuTeQ software, for lexicographic analysis, correspondence factor analysis, classification, similarity, and word cloud. Revelation of the words in the dendrogram assumed the following criteria: (a) frequency of the reduced forms equal to or greater than 4, and (b) greatest value of the chi-square test of the association of the reduced forms and of the elementary context units (ECUs) with each of the classes. The researchers respected the division of the corpus into text segments and in the respective thematic areas and classes. The interview coding procedures were performed by two authors with previous experience (O.Z., M.S.-S.).

The analysed corpus had 74 initial context units (ICUs), each participant being considered an ICU. Each ICU started with a command line, identifying the participant (part) and characteristics (variables) that were important for the research design, for example, the variables of age attribute (id), marital status (estcivil), school attended (escola), and nationality (nacional):

**** *part_01 *id_3 *estcivil_1 *escola_1 *nacional_1

To streamline the analysis process of the results, the six authors discussed the procedures.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Family and Academic Characterization

Sample consisting of 74 female master’s degree students aged 24–46 years (M = 32.05 ± 5.39). The socio-family and academic characterization is summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Socio-family and academic characterization.

3.2. Qualitative Data by IRaMuTeQ

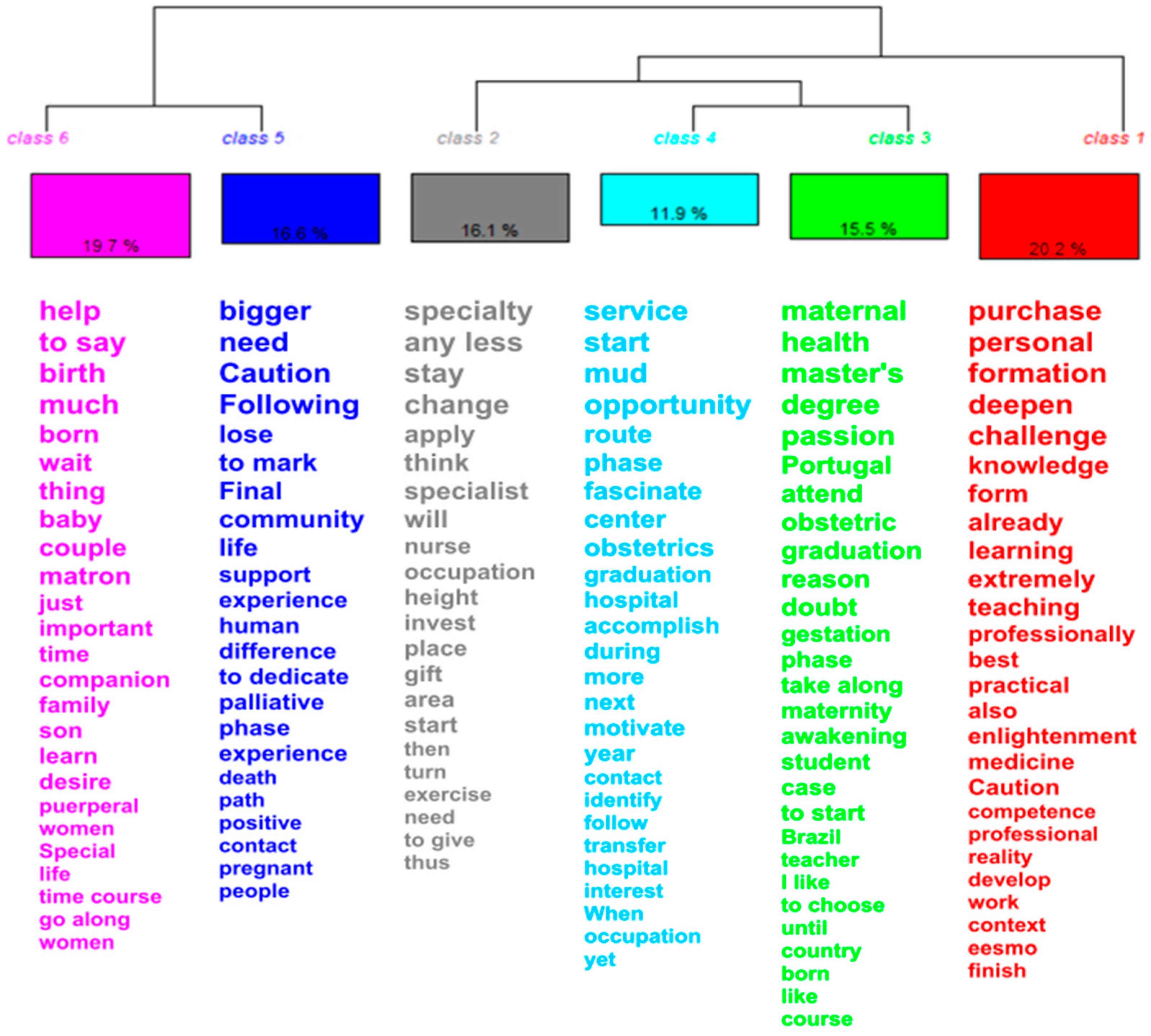

The following was observed in the qualitative analysis. The interviews constituted 220 ECUs. Of these, the software classified 193 text segments (TSs). Vocabulary richness was leveraged at 87.73%, from which six classes emerged through descending hierarchical classification (DHC).

The definition of classes by theme and hierarchical structure occurred as follows. In the first division, the corpus supported two thematic areas. Six classes emerged, recording the percentage of TSs categorizing each class. In the first division, Classes 5 and 6 were organized in one thematic area and Classes 1, 2, 3, and 4 in another. In the second thematic area, Class 1 was formed and, subsequently, the division of Class 2 and Classes 4 and 3 emerged. According to the representativeness of the content and the most frequently evoked words, the themes and classes were given names. In the appendix, Supplementary Table S1 exemplifies specific TSs by class and by the most significant word according to the DHC, as well as the name attributed to the six classes and themes.

Themes and Classes

According to the representativeness of the content and the most frequently evoked words, the following names were assigned to the themes and classes:

- Thematic area 1—Building a professional identity;

- Class 5—Motivation for technical competence;

- Class 6—Humanistic motivation for the care inherent to the species;

- Thematic area 2—Knowledge construction;

- Class 1—Motivation for the fascination of the profession;

- Class 2—Motivation to overcome adversity;

- Class 3—Motivation for the concrete knowledge area;

- Class 4—Motivation to attain a higher training level.

The intersection of Classes 1, 2, 3, and 4 is representative of the interest in acquiring knowledge in the field of MMP. It conveys the idea of “what I want to know how to do”, in the sense of cognitive-instrumental acquisition. Although proximity to Classes 6 and 5 is fainter, it reports on professional and personal experiences. The opportunities are combined in the sense of availability for care, safeguarding and help, which, in a humanistic way, preserve life. It conveys the idea of “what I want to be”, how I define myself.

Regarding the percentages obtained for each of the classes, it was verified that Class 1 covers 39/193 ECUs with a percentage of 20.21%, and thus that it is the most representative class of the corpus; Class 2 is made up of 31/193 ECUs, representing 16.06%; Class 3 has 30/193 ECUs, representing 15.54%; Class 4 includes 23/193 ECUs, representing 11.92%; Class 5 has 32/193 ECUs, representing 16.58%; and, finally, Class 6 has 38/193 ECUs, representing 19.58% of the total of ECUs (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Dendrogram of the descending hierarchical classification.

We also observed that, in the formation of Class 1, the Portuguese participants had more weight. In the formation of Class 2, we were able to verify that a married marital status and an age group from 25 to 29 years had more weight. Regarding Class 3, it was verified that the Brazilian and Cape Verdean nationalities had more weight, as well as being divorced, being aged 20–24 years, and belonging to the Évora school. In Class 4, the participants in stable unions and aged 25–29 years old contributed more. Class 5 was formed from the contributions of the participants who were from the Lisbon school, single, and aged 35–39 and 40–44 years. Finally, Class 6 had a greater contribution from the Spanish participants and those aged 45–49 years. Classes 1, 5, and 6 were peripheral, with faint paired interconnections between Classes 1 and 5 and between Classes 5 and 6. It is verified that Classes 2, 3, and 4 were the closest to one another, managing to maintain an interconnection with Classes 1, 5, and 6. Finally, it is noticeable that Class 2 had a central representation in the participants’ discourse (Supplementary Figure S1).

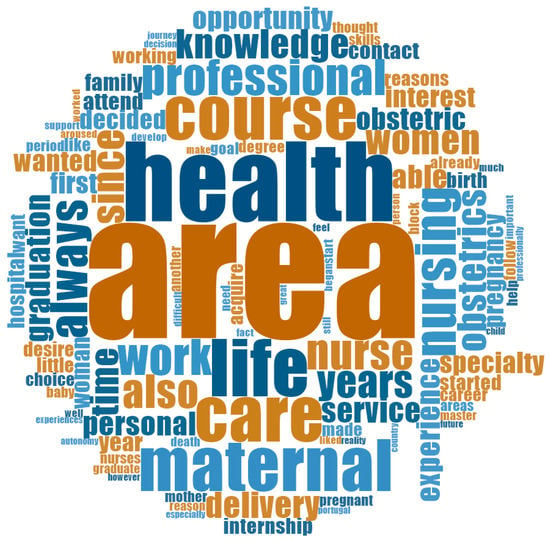

In the word cloud (Figure 2), it is verified that the central term of the discourse was area, that is, area of interest, knowledge area, most captivating area in nursing, and area of personal fulfilment in the nursing profession.

Figure 2.

Word cloud.

4. Discussion

The response rate of 78.9% is satisfactory, given the online application of the instrument. The understanding of the limits or recommendations for this rate is controversial, with the minimums varying accordingly between 10% and 20% [34]. For the sample size, the return rate is satisfactory [35]. The sample composition, mostly female, may have contributed to a high number of answers, leading to similar results [23]. The representation of women in the sample (94.6%) is in accordance with previous studies, where an approximate percentage representation for the profession is identified, with a social image linked to gender [36,37]. There is a certain conflict between believing that gender diversity is legitimate for the midwifery profession and simultaneously recognizing greater comfort in accepting that the caregiver is a female figure. The greater understanding that the female professional can offer, through life experience, can perhaps legitimize the career choice [37,38]. Such arguments were noticeable in the participants when they invoked their personal motherhood experiences as reasons for choosing the profession, conveying the idea of empathy through gender.

Class 1: Motivation for the fascination of the profession. The choice of the midwifery profession expresses idealization, through a social image, initiated in childhood and associated with gender. The evolutive or developmental theories of the 1950s (e.g., those of Eli Ginzberg, 1951) explain the phenomenon. In fact, professional choice can be a process that lasts for years, starting as a fantasy phase in childhood. This is evident in some participants’ statements.

(…) The interest and pleasure that I’ve always had in this area since I was a child; since I was a little girl, I remember that all my favourite dolls would either be pregnant or already had babies, that I used to make a maternity ward in my “baby house”. In the innocence of age, I said that I wanted to be a helper for mothers and babies.(N13)

Always, I always wanted to be a matron… to devote my whole life to helping more babies to be born…. this has been my main objective.(N33)

The participants invoke moments from their childhood in which desire and playful imagination are close. They refer to their childhood days when, not understanding what is necessary to achieve a career, they mimicked adults in displaying the profession. The trial phase will have appeared when they were aged between 12 and 16 years and had choices based on interests, abilities, and values. The realistic phase will have followed when they sought to reach a balance between desire and reality, as in the example of the following statement:

(…) I have a maternal instinct, despite not being a mother, and I chose the course because I like taking care of people.(N43)

My personal likes and the need to deepen my knowledge as a professional and personally drove me to want to attend the course.(N51)

Since the basic course studies (undergraduate degree in nursing) I’ve liked maternal health.(N60)

The participants will have already gone through the crystallization phase as they realized the option. They are currently in the specification phase, in other words, and are on their way to attaining the objective [39]. This is conveyed in their words:

(…) the search for challenges and change was the reason that brought me here to Portugal. I consider that what I learned has already been largely accomplished and, for that reason, I intend to acquire new knowledge that will allow for my personal and professional fulfilment.(N42)

An idealized view of midwifery is sometimes instilled through films and television series. The profession is romanticized in the media and midwives are often presented as heroines. This is common in health professions, perhaps most impactful in the youngest children who have no clear picture of the profession [40].

Class 2: Motivation to overcome adversity. In the motivation process, there is a moment that precipitates the future [3]. This moment occurs during deliberate and conscious decision-making about choice of the profession. This is evident in the participants’ statements:

(…) at that time, I knew exactly what I wanted to do, which direction I wanted to take in my career, and I decided to apply for the specialty of maternal and obstetric health.(N27)

Motivation is instilled in such a way that some statements reveal in fantasy the preview of professional quality and competence, before attaining it:

(…) despite the daily difficulties, after attending the course (undergraduate) I chose to stay in maternal health because I love the idea of becoming a specialist in such a specific and singular area… It will allow me to be an excellent nurse.(N8)

Anticipating the gratifying consequences seems to act as motivational reinforcement. However, the strength to continue to be motivated and to overcome difficulties is recognized, as stated by the following participant:

(…) I practised in parallel for 1 year and a half in another area knowing that what I was doing was in the area of maternal and obstetric health… After this period I changed institutions for family reasons, and it wasn’t possible for me to remain in the maternal health area… but now was the time to do it.(N13)

The results compete with those from studies in which barriers to the continuation of professional training are identified, such as lack of support from the employer or impossibility to reconcile family life with work and studies [41]. These results reflect those form other studies in which self-determination was one of the most relevant meanings [42].

Class 3: Motivation for the concrete knowledge area. These participants have been nurses for at least two years, and some have had previous contacts with maternal health care, which will have contributed to the modelling of their motivation:

(…) after my years as a student and as a professional (undergraduate) I’ve come to see that maternal and obstetric health is undoubtedly the area in which I feel most fulfilled and happy.(N56)

The preference for specific knowledge areas or domains is explained by the classic theories of motivation (Bandura’s social learning theory in 1977 and Ajzen’s theory of planned behaviour in 1991), having as a central element the person’s intention to put certain behaviours into practice [42]. In the area of maternal health, the beneficiaries of care are particularly different from those in other nursing specializations. Women and newborns, or the expanding family, are the focus of care. The motivation for the area can be so strong that there is perseverance to wait until the goal is achieved, as illustrated by the following participant’s speech:

(…) but I have waited for some time for the transfer request to the delivery room or obstetrics service in which I intend to develop my career, the master’s degree in maternal and obstetric health nursing; it was and would always be my first and only option for this new life project of mine.(N44)

Midwifery as a lifetime career pathway is identified in some qualitative studies as a personal calling to care for others. This strong personal identification with the work is shown in the pride in and passion for caring for women during family planning and pregnancy [3]. Despite the enthusiasm for the profession, midwives are scarce in both developed and in developing countries, even if access is easy. Perhaps, the stress associated with health professions is the largest obstacle [43], which becomes even greater when economic burdens increase, such as when studying away from home or abroad.

Even moving to another country, entering into another social or work culture, and pursuing one’s objectives can provide motivation:

(…) I’m motivated to have an experience abroad on obstetric care and obtain a master’s degree in maternal and obstetric health and I would like… who knows after the master’s degree to validate the diploma and practice nursing in Portugal or perhaps in another country.(N58)

Candidates who study midwifery in Portugal are subject to international guidelines (European Union Standards) according to articles 40–42, both in theory and in clinical practice, including in the quantification of experiences. The training curriculum with a total of 120 ECTS is divided into theory and practice and consists of the programmatic contents defined in the Declaration of Munich [44] and subsequently adopted in Portugal. Current education is the result of progress over the years since, in succession, regulation of training passed through Decree-Law No. 353/99 of 3 September (which instituted post-bachelor’s degrees), Decree-Law No. 74/2006 of 24 March, and Decree-Law No. 115/2013 of 7 August (which consolidated the teaching of master’s programs). In May 2019, the OE issued a guideline (SAI-OE/2019/4617) which, in addition to validating the course evaluation requirements, established that from 2020/2021 all higher education institutions must adopt training for an academic master’s degree. Thus, in Portugal, training in the maternal health area is at the second-cycle level. However, although it can occur in schools integrated into universities, it is not university education, as is the case in most European countries, the USA, and Brazil. In Spain, midwifery training is carried out via a “residency” format, with a two-year connection to the health institution where the training takes place. The regulation was implemented in 1992 and published in the Official State Bulletin (BOE, 2 June 1992). Spain opted for training accredited with the official title of specialist; that is, a graduate degree, and not an academic degree.

Class 4: Motivation to attain a higher training level. Statements such as the following suggest that the desire for higher education, with greater professional accreditation, was a source of motivation for the participants:

(…) in May I was transferred to the obstetrics service at the hospital centre, which motivated me even more to start this whole journey.(N18)

Such a statement suggests that, through contact with a more demanding care environment, the professional feels encouraged to attain a higher level. Other statements convey the idea of reinforcing motivation:

(…) I started investing in other areas, but then an opportunity arose in October to choose the possible maternal health area where I would like to start working.(N70)

As the social cognitive theory establishes, self-efficacy is developed through successful experiences [45]. It is surrounded by confidence and by perseverance toward objectives, as can be seen in the following statement:

(…) nearly 1 year and 1 month ago the transfer to the obstetrics service of my hospital was authorized and I felt the need to acquire more knowledge and skills, which is why I decided that this year was the right year to start the course.(N39)

The participant’s speech suggests that the vicarious reinforcement of the need to know more motivates more knowledge and strengthens responses, in view of the observation of behavioural results:

(…) waiting for a place defined by my hospital (Spain) will be too much for me… and I like the Portuguese model…. It is more…. There are other opportunities like Erasmus.(N18)

The Spanish training content is based on Directive 2005/36/EC of 7 September of the European Parliament, transposed into Royal Decree 1837/2008 of 8 November, and ratified in 2009 by the National Council of Specialties in Health Science (Order SAS/1349/2009 of 6 May). Based on the international guidelines, a training model privileging reflective teaching (which emphasizes rationality over practice) was established [24]. The students complete the training program in accredited health units in a period of two years, full-time, for 11 months of the year. They carry out a total of 3600 h in theoretical and clinical activities, with 26% (936 h) devoted to the acquisition of theoretical knowledge and 2664 to practice. Of the practical hours, 60–70% (from 1598 to 1864) are performed in a hospital environment and between 799 and 1065 are performed in primary care. Regarding the clinical experiences, the number of births students are required to attend is approximately twice the number required in the European Directive (BOE: assist a minimum of 80 normal births versus 40 births in the European Union Standards for Nursing and Midwifery) [44]. As midwifery training does not lead to an academic degree, Erasmus mobility is not possible. Given that the hospitals’ teaching units are not academic bodies, there is no possibility of foreigners carrying out internships there through Erasmus mobility, as it is not known or recognized as a higher education practice.

Class 5: Motivation for technical competence. In the last thematic area, the view of the midwifery profession, when focusing on the birth period, the woman, and the foetus/new-born, is in agreement with the humanistic and practical/clinical philosophical meanings [46]. The participants are sensitive to the clinical aspects and underline specific competences on the execution of the technique. The know-how-to-do, the correct actions, are valid for the specific field:

(…) during the reproductive cycle, midwives are considered as reference professionals for the provision of care to the woman in her family and community.(N29)

The participants recognize the need for technical and specialized knowledge, as recommended by the WHO [10,11,47]. In fact, even in the most remote places in the world, where formal/conventional health care does not exist or takes days to arrive, the specificity of midwife care is verified [48]. The participants underline the motivation for the profession through the profession’s unique skills in statements such as:

(…) I believe that in the future I can make a difference in the provision of autonomous and interdependent specialized care for those who need it most in the care process throughout the life cycle of women in our community.(N29)

The technical facet of the profession is indivisible from the humanistic one. There is a double focus in the interpersonal context that arises between the beneficiary/woman and the caregiver/midwife [46]. This is visible in the participants’ statements, when affective and emotional reasons emerge, expressed in the term “devotion”:

(…) in the course of my professional life I have had a lot of contact with the maternal health area and that is where I feel the most devotion.(N61)

Pride in the profession and the possibility of offering good-quality assistance is a personal and professional achievement [12]. Alternatively, as some authors claim, midwives love what they do [3,14].

Class 6: Humanistic motivation for the care inherent to the species. The results suggest that, in the participants, the motivation for the profession reflects the midwife described by Socrates in the maieutic approach. Personified in the woman-mother, the midwife teaches by age and experience. She is the one that brings virtue to light, the honest figure, with technical knowledge, practical skills, and, above all, patience [49].

(…) I have four children, all born through normal birth, but the last two were born in home births without interventions. All pregnancies were risk-free but in the first two births that were hospitalized, there were many interventions that made the experience not so positive, and I want to do it differently, do it well.(N37)

It is also to be considered that the Socratic method is grounded in critical thinking, widely applied in undergraduate education [50,51]. This can sustain an eventual legacy in the motivation for specialization in the current participants. On the other hand, in the socio-cultural environment, the Judeo-Christian tradition dominates, where the image of the midwife is present, helping all of them [52].

(…) and taking care of women at such an important time in their lives, during the birth of their baby, I was very enchanted during the undergraduate period (…) so I decided to learn more about maternal and obstetric health.(N47)

The statements suggest that the profession has a strong gender identity reinforcement [36]. On the other hand, motivation is anchored in supportive and attentive practice, assuming personal responsibility towards life before the community, offering trust and security [53]. This view is consistent with recommendations that the WHO has been making for some time: to focus care on the beneficiary/woman and to maintain a naturalistic view of the birth process [54]. A paradigm that other models underline and recognize is the core of the midwifery profession and the objective of training: being with the woman, as the word midwife implies [43].

(…) for me it is exciting and rewarding to be able to help care for and develop skills in this area from the time the pregnant woman enters until the baby is born and monitor her hospitalization and the new-born’s first days of life.(N44)

In the current study, the motivation for the profession is directed towards appropriation of the concept of a good midwife [55]. In Class 6, the participants idealize their professional image through attributes that agree with those from other studies [55,56], where theoretical knowledge, professional skills, personal qualities, communication skills, and ethical/moral values are fundamental requirements and reasons. The generosity of the caregiver, in face of the species’ altriciality and the fragility of the mother–newborn dyad, suggests that it is the dominant image of the midwifery profession, that is, the guidance for becoming a good midwife. The meaning of birth territory will have emerged in the participants [57].

5. Conclusions

The motivation for knowledge and the acquisition of a professional identity are the categories that dominate the narratives. The path of motivation for the profession is rooted in the fascination of childhood, fuelled by the proximity to the gender roles that were prominent in undergraduate training. The determination to make the decision to specialize as a midwife was deliberate, overcoming work and family obstacles. This brought feelings of personal fulfilment, through training experiences, which was projected for future gratification. Vicarious learning, or that of the professional learning environment, stimulated knowledge, modelling the image of the midwife as a valuable professional. The construction of the emerging image valued the knowledge and humanity of the interaction with mothers and newborns. In the sense of personal appreciation, professional autonomy, and technical competences/skills, professional identity is in the process of integration. The good midwife model is on the students’ professional horizon.

The narratives reveal a caring symbolism strongly rooted in the motivation to be a midwife. This study is to be considered a tribute to the ancestral role of midwives, joining voices with the Nursing/Midwifery Now movement.

Considering the results, we believe that the Directive’s guidelines provide for the regulation of the educational experiences. This facilitates the development of professional identity and the professional appropriation of the “birth territory”. However, the results suggest that the students long for humanist models in addition to these concrete guidelines. The Positive Childbirth movement launched by the WHO in 2018 is an example of this type of international model. The students’ emphasis on the diversity of caregiving experiences for women in the reproductive cycle suggests the need for flexible study plans that also meet the needs of women of diverse cultures. The high level of mobility in contemporary society, along with migratory movement and other acculturation processes, pose challenges for midwives, both due to cultural contexts and to the need to preserve the health of women. In fact, motherhood is a developmental crisis and the midwife can be a key element both in processes that take place harmoniously and in those in which uprooted women experience crises that are far from normal.

The results suggest that there will also be enthusiasm for research and a greater need to master knowledge and identify boundaries for gains in professional autonomy. In future studies it may be useful to carry out longitudinal research on expectations when starting the course and reflections on training experiences when finishing the course. This research could provide important insights for the improvement of education and midwifery practice.

6. Strengths and Limitations

The first limitation is the collection of testimonies through narratives, as interviews could have gathered more information. However, it offers opportunities for response time management, as it is not determined by the researcher, allowing for greater concentration without imposed limits. As a second limitation, there was a need to translate some narratives from Spanish to Portuguese. However, one of the authors’ strengths is linguistic proficiency in Spanish and the ability to interpret the language. One other core strength includes the midwifery students’ insights allowing for an in-depth analysis of the narratives and subject matters discussed.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/educsci12040243/s1, Table S1: Examples of specific text segments classified by class; Figure S1: Analysis of the factors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S.-S., A.S. and H.D.; methodology, M.S.-S., O.Z. and A.S.; software, M.S.-S., O.Z. and M.B.; validation, O.Z., A.F. and V.A.; formal analysis, M.S.-S., O.Z. and V.A.; investigation, M.B., A.F. and H.D.; resources, A.F., H.D. and A.S.; data curation, M.S.-S., M.B. and O.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S.-S., M.B. and O.Z.; writing—review and editing, M.S.-S., O.Z., A.F. and V.A.; visualization, H.D., A.F. and V.A.; supervision, M.B., A.S. and V.A.; project administration, M.S.-S., A.S. and H.D.; funding acquisition, not applicable. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board Ethics Committee for Research in the Areas of Human Health and Welfare of the University of Évora, resulting in approval (Registration No. 21006) at 26 January.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This study is dedicated to Midwifery students in Portugal. They are courageously working students, most of them without support from their employers. They return to their institution offering more quality and proficiency in care. They generously even have the time and spirit of collaboration to offer the testimonies that made this study possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Angel, E.; Craven, R.; Denson, N. The nurses’ self-concept instrument (NSCI): A comparison of domestic and international student nurses’ professional self-concepts from a large Australian University. Nurse Educ. Today 2012, 32, 636–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arthur, D.; Pang, S.; Wong, T.; Alexander, M.F.; Drury, J.; Eastwood, H.; Johansson, I.; Jooste, K.; Naude, M.; Noh, C.H.; et al. Caring attributes, professional self concept and technological influences in a sample of Registered Nurses in eleven countries. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 1999, 36, 387–396. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloxsome, D.; Bayes, S.; Ireson, D. I love being a midwife; it’s who I am: A Glaserian Grounded Theory Study of why midwives stay in midwifery. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 208–220. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matlala, M.S.; Lumadi, T.G. Perceptions of midwives on shortage and retention of staff at a public hospital in Tshwane District. Curationis 2019, 42, e1–e10. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, E.H.; Balsam, P.D. The Behavioral Neuroscience of Motivation: An Overview of Concepts, Measures, and Translational Applications. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci. 2016, 27, 1–12. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanfer, R.; Frese, M.; Johnson, R.E. Motivation related to work: A century of progress. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 338–355. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.; Shahzad, F.; Waqar, S.H. Seeking motivation for selecting Medical Profession as a Career Choice. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 36, 941–945. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebditch, M.; Daley, S.; Wright, J.; Sherlock, G.; Scott, J.; Banerjee, S. Preferences of nursing and medical students for working with older adults and people with dementia: A systematic review. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 92. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messineo, L.; Allegra, M.; Seta, L. Self-reported motivation for choosing nursing studies: A self-determination theory perspective. BMC Med. Educ. 2019, 19, 192. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Global Standards for the Initial Education of Professional Nurses and Midwives; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- WHO; WHO Europe Midwifery Curriculum for Qualified Nurses. WHO European Strategy for Continuing Education for Nurses and Midwives; World Health Organization: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bogren, M.; Grahn, M.; Kaboru, B.B.; Berg, M. Midwives’ challenges and factors that motivate them to remain in their workplace in the Democratic Republic of Congo—An interview study. Hum. Resour. Health 2020, 18, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E Homer, C.S.; Friberg, I.K.; Dias, M.A.B.; Hoope-Bender, P.T.; Sandall, J.; Speciale, A.M.; A Bartlett, L. The projected effect of scaling up midwifery. Lancet 2014, 384, 1146–1157. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, A.; Ferraguti, G.; Petrella, C.; Greco, A.; Ralli, M.; Vitali, M.; Malatesta, M.F.D.; Fiore, M.; Ceccanti, M.; Messina, M.P. Challenges for Midwives’ Healthcare Practice in the Next Decade: COVID-19-Global Climate Changes-Aging and Pregnancy-Gestational Alcohol Abuse. Clin. Ter. 2021, 171, e30–e36. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNFPA ICM; WHO. The State of the World’s Midwifery: A Universal Pathway, a Woman’s Right to Health; United Nation Population Fund: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dupin, C.-M.; Pinon, M.; Jaggi, K.; Teixera, C.; Sagne, A.; Delicado, N. Public health nursing education viewed through the lens of superdiversity: A resource for global health. BMC Nurs. 2020, 19, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermansson, E.; Mårtensson, L.B. The evolution of midwifery education at the master’s level: A study of Swedish midwifery education programmes after the implementation of the Bologna process. Nurse Educ. Today 2013, 33, 866–872. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mivšek, P.; Baškova, M.; Wilhelmova, R. Midwifery education in Central-Eastern Europe. Midwifery 2016, 33, 43–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, J.E. Experiences of student midwives learning and working abroad in Europe: The value of an Erasmus undergraduate midwifery education programme. Midwifery 2017, 44, 7–13. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosic, N.; Tomak, T. Professional and normative standards in midwifery in six Southeast European countries: A policy case study. Eur. J. Midwifery 2019, 3, 18. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, J.; Luyben, A.; O’Connell, R.; Gillen, P.; Escuriet, R.; Fleming, V. Failure or progress?: The current state of the professionalisation of midwifery in Europe. Eur. J. Midwifery 2019, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, M. Ajudar a Nascer—Parteiras, Saberes Obstétricos e Modelos de Formação (Seculo XV-1974); Universidade do Porto: Porto, Portugal, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Humar, L.; Sansoni, J. Bologna Process and Basic Nursing Education in 21 European Countries. Ann. Ig. 2017, 29, 561–571. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.; Gómez-Cantarino, S.; Silva, T.; Abéllan, M. Formación de matronas en España desde la segunda mitad del S. XX hasta la actialidad. Rev. Enferm. Ref. IV 2014, 4, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, K.; Trevathan, W. Evolutionary obstetrics. Evol. Med. Public Health 2014, 1, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Walrath, D. Rethinking Pelvic Typologies and the Human Birth Mechanism. Curr. Anthropol. 2003, 44, 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anna, M.-A.; Olga, C.-V.; Rocío, C.S.; Isabel, S.P.; Xavier, E.-T.; Pablo, R.C.; Montserrat, P.A.; Cristina, G.-B.; Ramon, E. Midwives’ experiences of the factors that facilitate normal birth among low risk women in public hospitals in Catalonia (Spain). Midwifery 2020, 88, 102752. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Salazar, S.; Ramos-Morcillo, A.J.; Leal-Costa, C.; García-González, J.; Hernández-Méndez, S.; Ruzafa-Martínez, M. Evidence-Based Practice competency and associated factors among Primary Care nurses in Spain. Aten. Primaria 2021, 53, 102050. (In Spain) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullerton, J.T.; Thompson, J.B.; Johnson, P. Competency-based education: The essential basis of pre-service education for the professional midwifery workforce. Midwifery 2013, 29, 1129–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Midwives (PP) per 100 000. World Health Organization. Available online: https://gateway.euro.who.int/en/indicators/hfa_520-5350-midwives-pp-per-100-000/ (accessed on 5 August 2020).

- Büscher, A.; Sivertsen, B.; White, J. Nurses and Midwives: A Force for Health; World Health Organization: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Morse, J.; Field, P. Nursing Research. The Application of Qualitative Approaches; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- van Mol, C. Improving web survey efficiency: The impact of an extra reminder and reminder content on web survey response. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2017, 20, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nulty, D.D. The adequacy of response rates to online and paper surveys: What can be done? Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2008, 33, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, H.; Lima, L. Do ser mulher.... ao ser enfermeira: Cuidar na perspetiva de género. Psicol. Teor. Investig. Prática 2003, 2, 205–231. [Google Scholar]

- Bly, K.C.; Ellis, S.A.; Ritter, R.J.; Kantrowitz-Gordon, I. A Survey of Midwives’ Attitudes Toward Men in Midwifery. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 2020, 65, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likis, F.E.; King, T.L. Gender Diversity and Inclusion in Midwifery. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 2020, 65, 193–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millan, L. Vocação Médica: Um Estudo de Género; Casa do Psicólogo: São Paulo, Brazil, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Terry, D.; Peck, B. Television as a Career Motivator and Education Tool: A Final-Year Nursing Student Cohort Study. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2020, 10, 346–357. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, C.; Christine, C.; McGuire, D. The motivation of nurses to participate in continuing professional education in Ireland. J. Eur. Ind. Train. 2006, 30, 365–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, H.; Lautenschläger, A. Career Choice Motivations of University Students. Int. J. Bus. Adm. 2011, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gillen, P. Connecting Status and Professional Learning: An Analysis of Midwives Career Using the Place © Model. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. European Union Standarts for Nursing and Midwifery Information for Accession Countries; World Health Organization: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action; Prentice-Hall, Inc.: Englewood, NJ, USA, 1986; Volume 1986, pp. 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Fontein-Kuipers, Y.; de Groot, R.; van Staa, A. Woman-centered care 2.0: Bringing the concept into focus. Eur. J. Midwifery 2018, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Midwifery Educator Core Competencies: Building Capacities of Midwifery Educators; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, T.; Smith, H. Establishing partnership with traditional birth attendants for improved maternal and newborn health: A review of factors influencing implementation. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017, 17, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnyeat, M.F. Socratic Midwifery, Platonic Inspiration. Bull. Inst. Class. Stud. 1977, 24, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papathanasiou, I.V.; Kleisiaris, C.F.; Fradelos, E.C.; Kakou, K.; Kourkouta, L. Critical thinking: The development of an essential skill for nursing students. Acta Inform. Med. 2014, 22, 283–286. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhene, A. The use of the Socratic inquiry to facilitate critical thinking in nursing education. Health SA Gesondheid 2019, 24, 1224. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaton, H.J. Mapping the literature of nurse-midwifery. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2006, 94 (Suppl. S2), E80–E86. (In English) [Google Scholar]

- Borges, M.; Pinho, D.; Santos, S. As representações sociais das parteiras tradicionais e o seu modo de cuidar. Cad. CEDES 2009, 29, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. WHO Recommendations: Intrapartum Care for a Positive Childbirth Experience: Web Annex; Evidence Base; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Issue CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/260215 (accessed on 28 December 2019).

- Borrelli, S.E. What is a good midwife? Insights from the literature. Midwifery 2014, 30, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odent, M. Do We Need Midwives? Pinter & Martin: Hampshire, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fahy, K.M.; Parratt, J.A. Birth Territory: A theory for midwifery practice. Women Birth 2006, 19, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).