1. Introduction

Baccalaureate school (

Gymnasium) (Information on the denomination and descriptions of the different educational pathways can be found at

https://www.edk.ch/en/education-system/basics, accessed 10 March 2022) at the upper-secondary level is the royal road to universities in Switzerland, although new pathways have been institutionalized in recent decades [

1,

2]. Consequently, in the public, in politics, and in the educational sciences, discussions repeatedly arise as to whether access to baccalaureate school is fair and equal. On the one hand, previous research has well documented, and frequently denounced, inequalities related to individual characteristics, particularly to social origin [

3,

4,

5]. Social origin influences the transition to baccalaureate school and leads to educational inequalities, even when we control for the academic performance of pupils. On the other hand, scholars have problematized the great variation in the proportion of pupils in baccalaureate school between and within cantons, which cannot solely be explained by differences in pupil performance [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10].

Studies that deal with the impact of regional factors on educational transitions have concluded that institutional factors of the cantonal educational system—in particular, the extent of separation at the lower-secondary level [

3,

11,

12] or the infrastructure, namely the provision of places in educational institutions [

13,

14,

15]—can play a decisive role in the opportunity of access to certain educational tracks. Moreover, the socio-spatial factors of a community, such as the level of urbanization, the economic structure, and the social structure of the population [

3,

7,

8,

16,

17,

18,

19], can also play a role.

So far, however, research has paid little attention to the dimensions of educational and socio-spatial structures of cantons and communities that moderate a pupil’s chances of being enrolled in baccalaureate school. An exception is the study by Buchmann, Kriesi, Koomen, Imdorf, and Basler [

13], which investigated the role of the cantonal proportion of baccalaureate degrees as well as of entry exams in regulating admission. At the same time, the degree of social inequality in access between cantons as it relates to the cantonal educational provisioning of places at baccalaureate school—one of the main structural conditions that varies between the cantons—has been neglected in recent research. An important exception for Switzerland is the study by Combet [

7]. She analyzed the impact of three different features of cantonal education systems from the perspective of social inequality, although she remained focused on the transition from primary school to the highest track in lower-secondary level—the pre- or long-term baccalaureate school—and did not take into account the cantonal educational provisioning of places at baccalaureate school. Another exception is the study by Sixt [

20], which, however, concentrates exclusively on Germany.

This paper therefore aims to answer the two following questions: (1) How do educational and socio-spatial structures of cantons and municipalities impact pupils’ access to baccalaureate school? (2) How does inequality vary between pupils from different social origins due to variations in the cantonal educational provisioning of places at baccalaureate school? For our theoretical foundation, we combined concepts of neo-institutionalism with the mechanism of social reproduction in education. Empirically, we analyzed national longitudinal register data to model educational transitions from compulsory school to baccalaureate school at the upper-secondary level by applying logistic regression models.

This article is structured as follows.

Section 2 briefly describes the main structures of the Swiss education system.

Section 3 outlines the state of research on individual and regional factors of access to baccalaureate school.

Section 4 depicts the data and methods used in our empirical analysis. The results on regional variance and its impact on being enrolled in baccalaureate school as well as the consequences of social inequalities in gaining access are presented in

Section 5.

Section 6 summarizes these findings and presents our corresponding conclusions.

2. Transition from Compulsory Schooling to Baccalaureate School: Varying Institutional Conditions in the Swiss Federal Education System

At the transition from lower- to upper-secondary education, 95% of the pupils in Switzerland enter one of the three federally certified pathways within two years after completing their compulsory education. One-fifth enroll in baccalaureate school, 5% choose upper-secondary specialized school, and two-thirds start a vocational education and training program, which is mostly organized in the form of apprenticeships [

16]. Baccalaureate school is the most demanding of these paths in terms of academic performance. Young people who complete this track with a baccalaureate are formally entitled to enroll in all types of higher-education institutions: traditional cantonal and federal universities, universities of applied sciences, and universities of teacher education. However, if they wish to study at a university of applied sciences, they need one year of practical experience in the form of an internship. In contrast, the two other pathways for upper-secondary education have staggered degrees, which means that additional educational achievements and exams are required after the first diploma in order to enroll in universities.

Baccalaureate school is still set up as an elitist route for the social reproduction of the upper class, a sort of royal road to universities, although new pathways to university education have been introduced in the last three decades [

1,

2]. At the transition to higher education, 95% of pupils who graduated with a baccalaureate diploma from baccalaureate school enter a university, with 77% going to a traditional university, which alone has the right to award doctorates. In comparison, when attending upper-secondary specialized school or vocational education and training, the transition rate to university education is much lower [

21], and graduates with a baccalaureate from the specialized school or the vocational education and training program have formal access only to universities of applied sciences.

The Swiss education system of compulsory schooling and general education at the upper-secondary level is characterized by educational federalism that is firmly anchored both in regulations and at the cultural level [

22,

23]. Such federalism is rooted in the cantonalization of educational structures from the 19th century onward [

24]. This federal system provides for the far-reaching autonomy of the 26 Swiss cantons in educational policy. As a consequence, the cantons provide different educational structures and apply different regulations in the governance of educational transitions in terms of educational provision and admission regulations [

8,

25,

26,

27]. Considerable differences, however, also exist at the municipal level. Cantons in German-speaking Switzerland in particular delegate many legislative and administrative tasks to local governments, whereas the French- and Italian-speaking regions rather exercise their educational authority through strong, centralized state bureaucracies [

22].

Common to all cantons, however, are the two transitions from the primary to lower-secondary level and from the lower-secondary to upper-secondary level, which involve selection processes and lead to subsequent performance tracking and unequal opportunities of education at the tertiary level [

11,

13]. The differentiated system in Switzerland leads to an accentuation of social inequalities in the educational pathways [

13]. At a very early stage in their lives, pupils are assigned after primary school to different tracks at the lower-secondary level that group pupils according to their educational performance. Research has shown that the educational pathways at the transition from lower- to upper-secondary school are shaped to a large extent by sorting pupils along social classes into the tracked system at the end of primary school [

10,

11,

13,

28,

29]. Depending on the canton, the number of tracks varies between two and four, and each track can be classified as a level with basic or advanced requirements. Apart from these segregated models where children are assigned according to a fixed requirement level for all subjects, private schools in particular, as well as certain cantons and communities, have more permeable and inclusive models [

30]. In these models, no separation along these lines exists; children continue to be taught together in the same class. Only in selected subjects is ability grouping implemented, whereby children attend classes according to their performance level in the given subject.

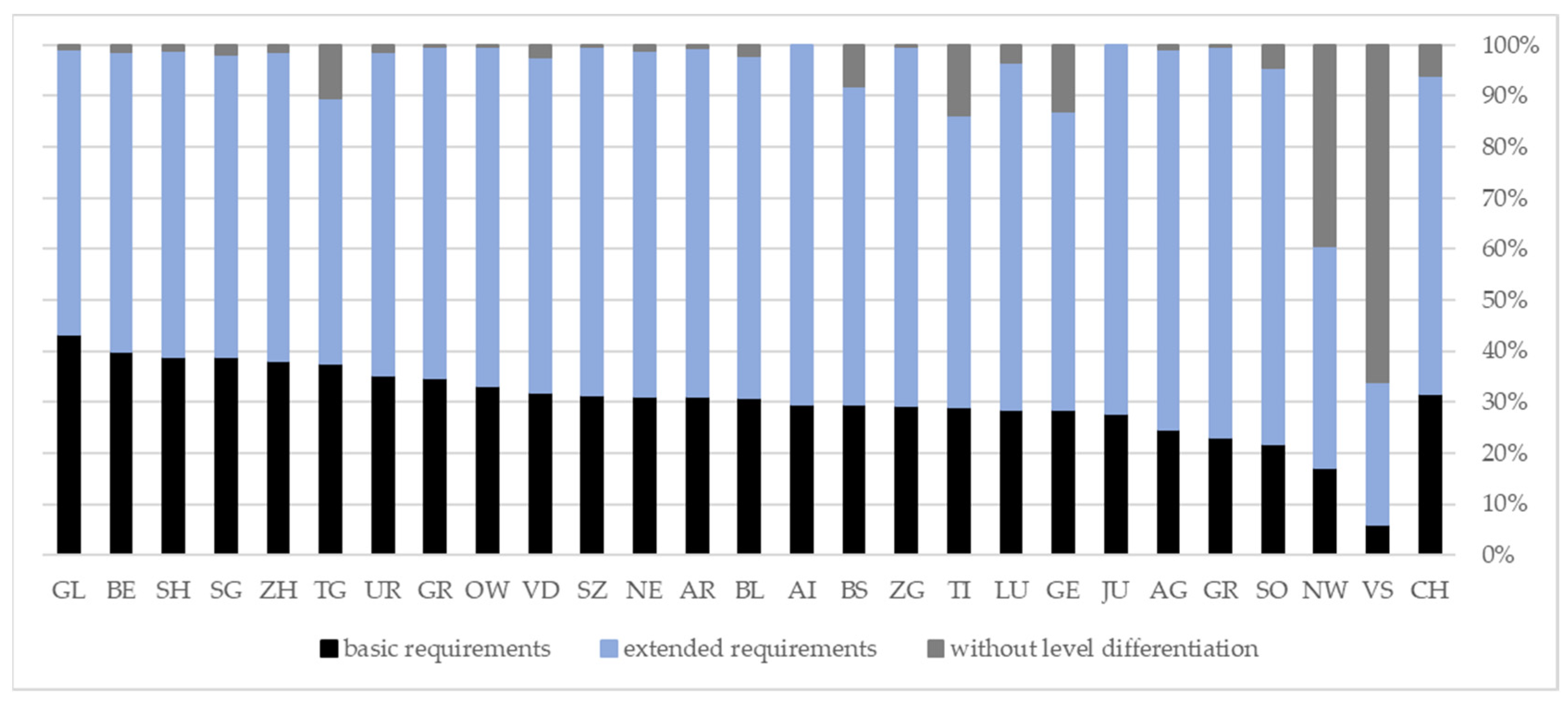

As

Figure 1 shows, the proportion of the two levels is different among the cantons, which implies unequal opportunities among the cantons [

7]. Only a few cantons offer a comprehensive system without level differentiation (an integrated model). Furthermore, in some cantons, children can already enter baccalaureate school at the end of primary schooling (long-term baccalaureate) or after the first or second year of lower-secondary education. (In

Figure 1, this “pre-baccalaureate track” is integrated into the advanced-requirement track). The municipalities of certain cantons have a great deal of leeway in implementing cantonal guidelines. The extent to which pupils are separated into different tracks, the number and permeability of tracks, and the distribution of pupils between the two requirement levels can therefore greatly differ within cantons [

8,

11].

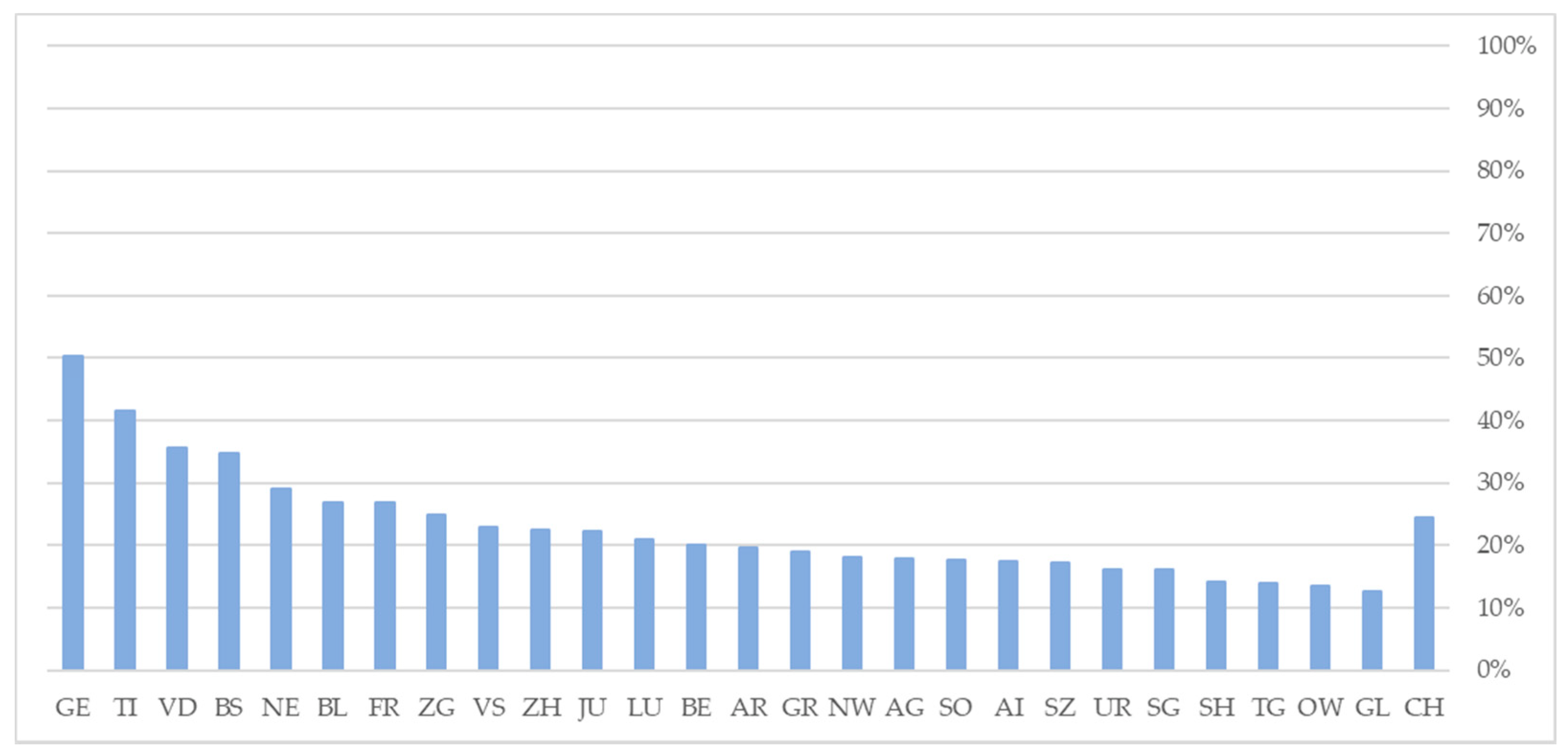

Furthermore, the proportion of pupils who enter baccalaureate school varies greatly by canton. As

Figure 2 demonstrates, this proportion is between 13% and more than 50%. A closer look at the cantons shows that the cantons in French- and Italian-speaking Switzerland (GE, TI, VD, NE, FR, VS, and JU) as well as the city cantons (GE and BS) have a higher proportion of pupils entering baccalaureate school than most of the German-speaking cantons.

4. Data and Methods

4.1. Data and Sample Selection

In our study, we analyzed new and unique longitudinal register data for Switzerland (Longitudinal Analyses in Education (LABB)) provided by the Swiss Federal Statistical Office (FSO). These data were created by linking different educational statistics via the social -security number of the pupils. As a result, we were able to analyze a full survey on the educational trajectories of the entire population of all learners in the Swiss education system since 2011 [

16] (p. 7). We focused on the cohort of 15- to 18-year-old pupils who graduated from lower-secondary school in 2013 and examined their initial transition to baccalaureate school over five years, leading up to 2018. Excluded were those pupils who had either not initially been part of the permanent resident population of Switzerland in 2013 (The permanent resident population includes all Swiss nationals with their main place of residence in Switzerland, as well as foreign nationals who have held a residence or permanent residence permit for at least 12 months (

https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/en/home/statistics/population/effectif-change/population.html, accessed on 10 March 2022), who had attended a program that was not part of compulsory education, or who had left Switzerland without entering certifying upper-secondary education [

16] (p. 11).

For the construction of the social origin variable, we used information on the parents’ highest level of educational attainment. In the LABB dataset, this is only available for 11% of the pupils of our cohort, as this information comes from the Swiss Structural Survey (unweighted n = 9501), which is a 10% sample of the permanent resident population aged 15 years and over in private households.

4.2. Method

We applied logistic regressions on this sample to explain entry into baccalaureate school. This is the appropriate method since the small number of 26 cantonal units in Switzerland and the sample size did not allow us to carry out multilevel logistic analysis (MLA). (MLA could take into account that individuals are nested within municipalities and cantons and that the probability of school entry varies among those structural units.)

We calculated blockwise regression models to test whether communal and cantonal variables could make an additional explanatory contribution compared to the model with individual variables (see

Table A4 and

Table A5 in

Appendix A). Since the information on social origin in the LABB data comes from the stratified sample of the structural survey, the cases were weighted accordingly in the regression models.

4.3. Dependent Variable: Entry into Baccalaureate School after Compulsory Education

As a dependent variable, we examined whether pupils enter baccalaureate school within five years after completing compulsory schooling. Because the register data do not contain subjective information on educational aspirations and decisions, it is not possible to analyze the mechanisms leading to entry (i.e., to distinguish between intention to enter baccalaureate school and a successful transition). Thus, it is not possible to determine to what extent entry into baccalaureate school is a consequence of the interplay of educational aspirations of pupils and their families, of self-selection and investment, of regional educational offerings, and of selection processes by the sending and receiving schools.

4.4. Explanatory Variables: Regional Structures of Cantons and Municipalities

As explanatory variables, we considered municipal and cantonal characteristics in our analysis (see

Table A1 in

Appendix A for the variable overview, including the descriptives). As an important regional variable at the cantonal level, we considered the

cantonal provisioning of places in baccalaureate schools. This was measured by the mean proportion of pupils under 20 years of age attending baccalaureate school in a canton from 2009 to 2013 (as a percentage). It is based on the Statistics of Pupils and Students provided by the FSO. (Due to missing data, the value of the Obwald canton refers to 2012, and the value of the Appenzell Inner-Rhodes canton refers to 2016). In principle, it would be possible for the cantonal offering to be higher than the demand indicated by the pupils. However, this seems rather unlikely in view of the current situation of competition and selection, and it is therefore appropriate to use this indicator, especially since the cantons do not provide any official information on this.

The

municipal urbanization variable distinguishes among urban, intermediate, and rural municipalities. Intermediate means dense peri-urban areas and rural centers. The municipal proportion of pupils in tracks with basic requirements and the proportion of pupils in tracks without level differentiation, which were calculated on the basis of the population of our cohort in the LABB data, are important for investigating differences in the chances to enroll in baccalaureate school between municipalities. The

municipal proportion of pupils in tracks with basic requirements was measured as the proportion of pupils in tracks with basic requirements relative to all pupils in the tracks with basic and advanced requirements to capture the extent of segregation within the tracked school model. As

Figure 1 shows, the integrated school model is anchored differently in the cantons, and the proportion of pupils in tracks without level differentiation varies greatly among municipalities. (For 20 municipalities, mainly in the canton Valais, where all pupils attend tracks without level differentiation, we imputed the cantonal median of the proportion of pupils in tracks with basic requirements.) The

proportion of pupils in tracks without level differentiation was measured as the proportion of pupils in tracks without level differentiation relative to all pupils of the population of our cohort in a municipality. All the variables at the municipal level refer to the pupils’ municipality of residence at the end of compulsory schooling in 2013.

We used the social composition of the entire body of pupils to analyze and control for the

social composition of the population in a municipality. (There are currently no ways to obtain or calculate the composition of the population by educational status at the municipality level. The Swiss Structural Survey contains information on the highest educational status in the household, but it is not representative for all municipalities.) For this purpose, we constructed two variables that measure the

proportion of pupils from western and from southern countries in a municipality, respectively. The former category is an indicator of the proportion of highly qualified immigrants who belong to the migration wave of the last 20 years and who hold academic aspirations for their children, whereas the latter is a proxy for the proportion of less educated immigrants who belong to the migration wave of refugees and low-qualified labor migration from the 1980s onward [

21,

64]. (For further information, see

Appendix A Note A1 and

Table A2 and

Table A3.)

4.5. Control Variables: Completed Track at the Lower-Secondary Level and Sociodemographic Characteristics of Pupils

The LABB data do not contain any information on the pupils’ academic performance. Therefore, individual achievement can only be indirectly and partially controlled for via the completed

track at the lower-secondary level. Nevertheless, we should be aware that there is a considerable overlap in competence across track types [

65].

We used two types of categorizations of the track at the lower-secondary level. For the first, we distinguished between pupils who attended tracks with basic requirements (including tracks with a special curriculum), tracks without level differentiation, and tracks with advanced requirements. For the second, we additionally differentiated the latter category into the pre-baccalaureate track (including all tracks of the various cantonal category systems that contain “Gymnasium” or “MAR” in their name) and the general track with advanced requirements.

With regard to the sociodemographic characteristics, we controlled for gender (dummy), age at the end of compulsory education (ordinal variable of 15 to 18 years), and migration status (i.e., born in Switzerland or abroad). Social origin was measured by the highest educational degree in the household (i.e., achieved by parents), where we distinguished between three categories: academic education (traditional university, university of applied sciences, or university of teacher education), intermediate education (diploma of secondary-level education like vocational education and training or baccalaureate, as well as professional education and training at the tertiary level), and compulsory education (primary or lower-secondary education).

4.6. Reported Effects

To address our research questions, we report predicted margins (PM) and average marginal effects (AME) of entering baccalaureate school. PM are average predicted probabilities based on model estimation using logistic regression. AME in the sense of absolute distance measures are the percentage-point differences of the PM, and the significance test checks whether they are different from zero [

66].

To answer our second research question, our focus is on the interaction effect between pupils’ social origin and the cantonal provisioning of baccalaureate school places. This allows us to capture how social origin affects the transitional probability, depending on cantonal baccalaureate school provision. We visualized the inequality between pupils of different social origin by plotting the PM and AME of the group with the highest and the lowest status of parental education in comparison to the intermediate status of parental education.

5. Results

We present two models. In model 1, the completed track at the lower-secondary level comprises three categories (basic requirements, without level differentiation, and advanced requirements). By contrast, in model 2, we distinguish four categories by differentiating the track with advanced requirements into the pre-baccalaureate track and the general track with advanced requirements. Pupils who attended the pre-baccalaureate track had already entered the baccalaureate school at the lower-secondary level. For them, it is therefore less a question of managing a transition to baccalaureate school than a question of remaining or not being promoted and instead opting out and starting upper-secondary specialized school or applying for an apprenticeship.

In

Section 5.1, we discuss the effect of these different tracks on enrolling in baccalaureate school. In

Section 5.2, we answer the first research question by reporting how the regional structures of cantons and municipalities—such as the fluctuating cantonal offering of baccalaureate school places and the different composition of the pupil body in municipalities—impact access to baccalaureate school. To answer the second research question, we present results on how inequality in access to baccalaureate school varies between pupils of different social origin according to the varying cantonal provision of places at baccalaureate school (

Section 5.3). In answering the two research questions, we compare the results of each of the two models.

5.1. Completed Track at the Lower-Secondary Level

As we can see in

Table 1 (model 1), the track at the lower-secondary level plays a crucial role. While the pupils who attended tracks with advanced requirements have a probability of 36% of advancing to baccalaureate school, the pupils in tracks with basic requirements in fact have hardly any chance (1%) of entering this school type. By contrast, the pupils who attended an integrated model without level differentiation have a higher probability of 10%.

Model 2, however, demonstrates that the pupils who entered the pre-baccalaureate track during their lower-secondary schooling are most likely to attend the baccalaureate school at the upper-secondary level. Their probability is nearly 83%, whereas the probability of the pupils in the general track with advanced requirements drops to the level of those in the integrated model. Several predictors of the explanatory regional variables change as a result of this differentiation of the level with advanced requirements. We will discuss this in more detail in

Section 5.2.

5.2. Cantonal and Municipal Factors in Access to Baccalaureate School

Along with the completed track at the lower-secondary level and sociodemographic factors, regional factors play a substantial role in determining baccalaureate school entrance.

Table A3 and

Table A4 in

Appendix A show that the regression models improve if we add cantonal and municipal factors. McFadden’s Adj R

2 increases from 24% to 28% (model 1a to model 1c) and from 49% to 53% (model 2a to model 2c), and Akaike decreases to an extent that provides very strong support for the augmented models. Although McFadden’s Adj R

2 should be interpreted with caution, we note that it is about twice as high for model 2 than for model 1. This suggests that model 2 with the completed 4-category track at the lower-secondary level fits better than model 1.

Unsurprisingly, our analyses show a positive effect of the

cantonal provisioning of places at baccalaureate schools on the individual transition of lower-secondary school graduates. The greater the supply of baccalaureate school places in a canton, the higher the probability that a pupil will attend. This is consistent with previous research [

13] and with our assumption in Hypothesis H1. This can be explained by the fact that the available supply of places is generally smaller than the number of pupils who aspire toward baccalaureate school. If the number of available places is expanded, more pupils transfer to baccalaureate school.

Let us now turn to the relation between the communal structure of lower-secondary education and attendance of baccalaureate school. The results of both models are consistent with Hypothesis H4 and show that the urbanization of a municipality influences the rate of transition to baccalaureate school. If lower-secondary school graduates live in urban communities, they are more likely to choose baccalaureate school than if they live in an intermediate area (e.g., dense peri-urban areas or rural centers) or in a rural area. This can be explained by the fact that the supply of apprenticeship places as an alternative educational path may be lower, and the supply of well-qualified jobs in the service sector may be higher, which fosters academic aspirations.

The municipal proportion of pupils in tracks with basic requirements shows a significant negative effect at the 10% significance level in model 2 but not in model 1. We can conclude that as soon as the pupils in the pre-baccalaureate track are recorded separately, there are signs of the expected relation as spelled out in Hypothesis H2. In municipalities with a larger proportion of pupils in tracks with basic requirements, vocational education and training is a valid alternative to baccalaureate school. This decreases the probability of a pupil entering baccalaureate school.

By contrast, the probability of a pupil entering baccalaureate school increases with the municipal proportion of pupils in tracks without level differentiation in model 1 but not in model 2. The larger the proportion of pupils within models without established level differentiation in a municipality, the higher the probability of an individual pupil attending such a model, and the higher the probability that the pupil will enter baccalaureate school after compulsory education (Hypothesis H3). We explain this positive influence by the fact that inclusive education leaves more options open for individual pupils and enables greater institutional permeability. However, it seems that this municipal effect is lost when differentiation is implemented. We were unable to find a conclusive explanation for this.

The social composition of the pupil body in the municipalities also plays an important role in model 1 (Hypothesis H5). The higher the proportion of pupils from western countries in a municipality, the more likely school graduates are to enter baccalaureate school. In contrast, as we postulated, the municipal proportion of pupils from southern countries indicates a negative relationship. These effects show that communal differences in the social composition of the pupil body are important for entry into baccalaureate school and that pupils in less well-off communities have fewer opportunities. However, this relationship disappears as soon as the pupils from the pre-baccalaureate school are introduced separately (model 2). We can conclude that in municipalities with a high proportion of academically educated parents, children often attend the pre-baccalaureate school, and as a result, this municipal effect is already absorbed in the fourth category by this earlier transition. Descriptive analyses of the social origin of the pupils in the two tracks with advanced requirements confirm this assumption. In 42% of the cases, the pupils in the pre-baccalaureate track originate from an academically educated family, whereas this percentage is only 19% for pupils in the general track with advanced requirements.

5.3. Sociodemographic Factors in Access to Baccalaureate School

The sociodemographic factors of gender, social origin, and age influence the transition to baccalaureate school which, ceteris paribus, complies with the state of research. Female pupils are more likely to start baccalaureate school than male pupils are. Pupils with at least one academically educated parent are much more likely to transfer to a baccalaureate school, and pupils whose parents completed no more than compulsory schooling are significantly less likely to do so, especially when we compare them with those pupils whose parents achieved an intermediate educational degree. The younger the pupils are, the more likely they are to transfer. Whether a pupil was born in Switzerland or abroad, on the other hand, seems to be altogether irrelevant.

5.4. Inequality Due to Cantonal Structures of Educational Provision

Does inequality between pupils of different social origin vary due to different cantonal educational provisioning of baccalaureate places? On average, pupils with a family background of academic education have a transitional probability of 44% (see

Table 1, model 1); those with a family background of intermediate education have a probability of 22%; and those with a family background of compulsory education have a probability of 15%. These differences are statistically significant. This means that pupils from privileged family backgrounds differ much more in their probability of entering baccalaureate school from the group with an intermediate family educational background than the latter from the group with the lowest family educational background. These differences between the probabilities of the three social groups appear to narrow when the track with advanced requirements is split into the pre-baccalaureate track and the general track with advanced requirements (

Table 1, model 2).

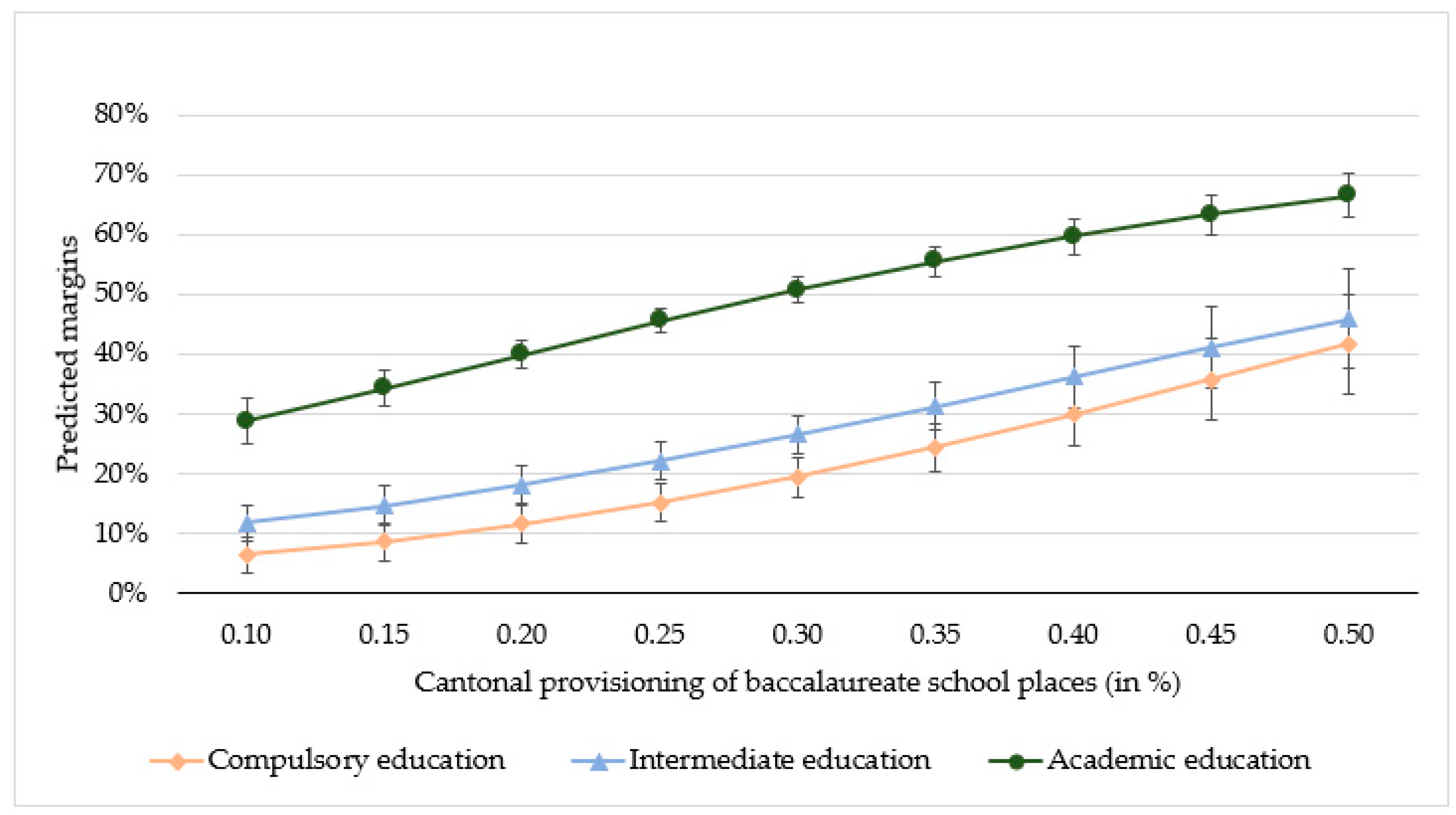

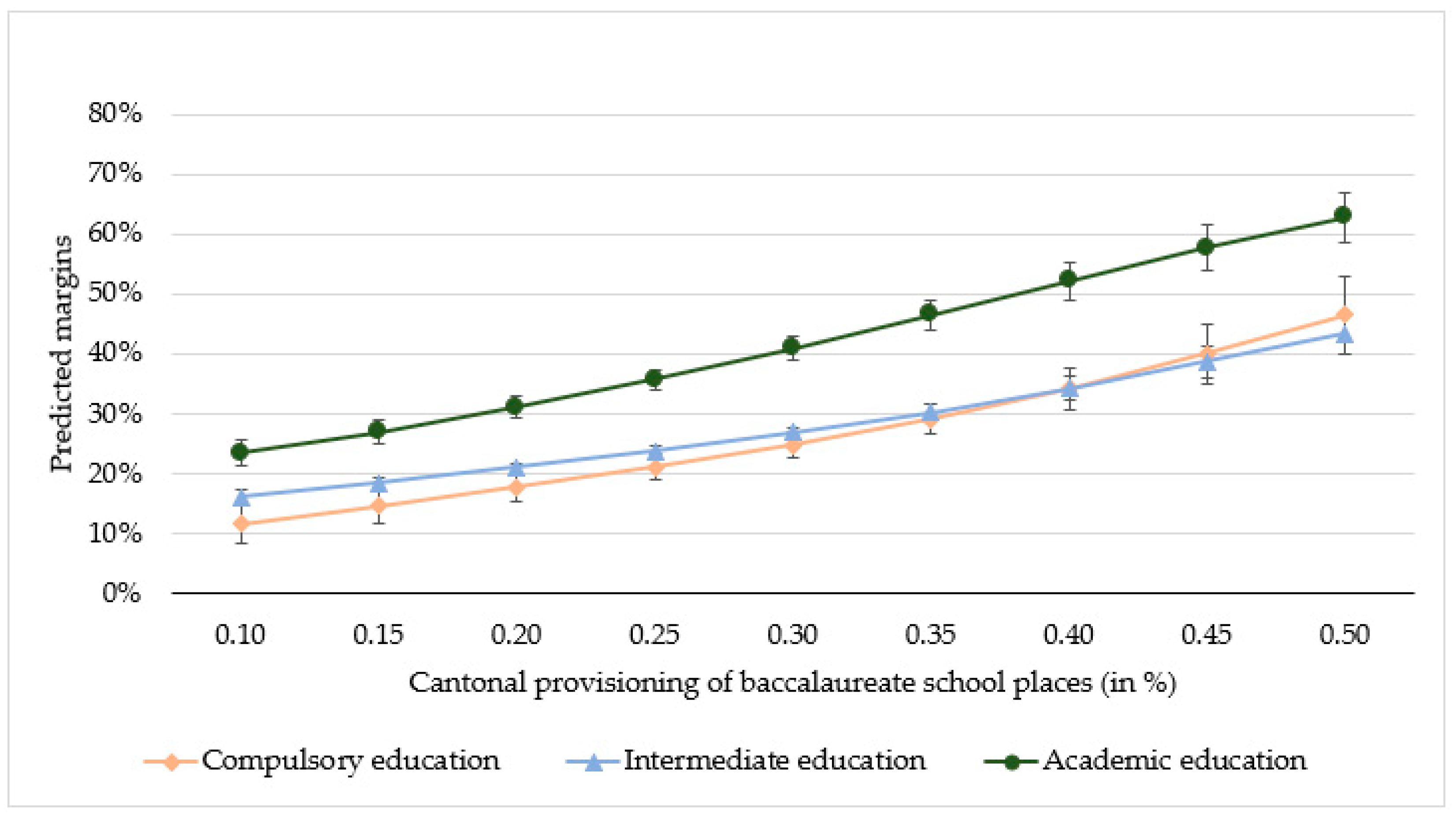

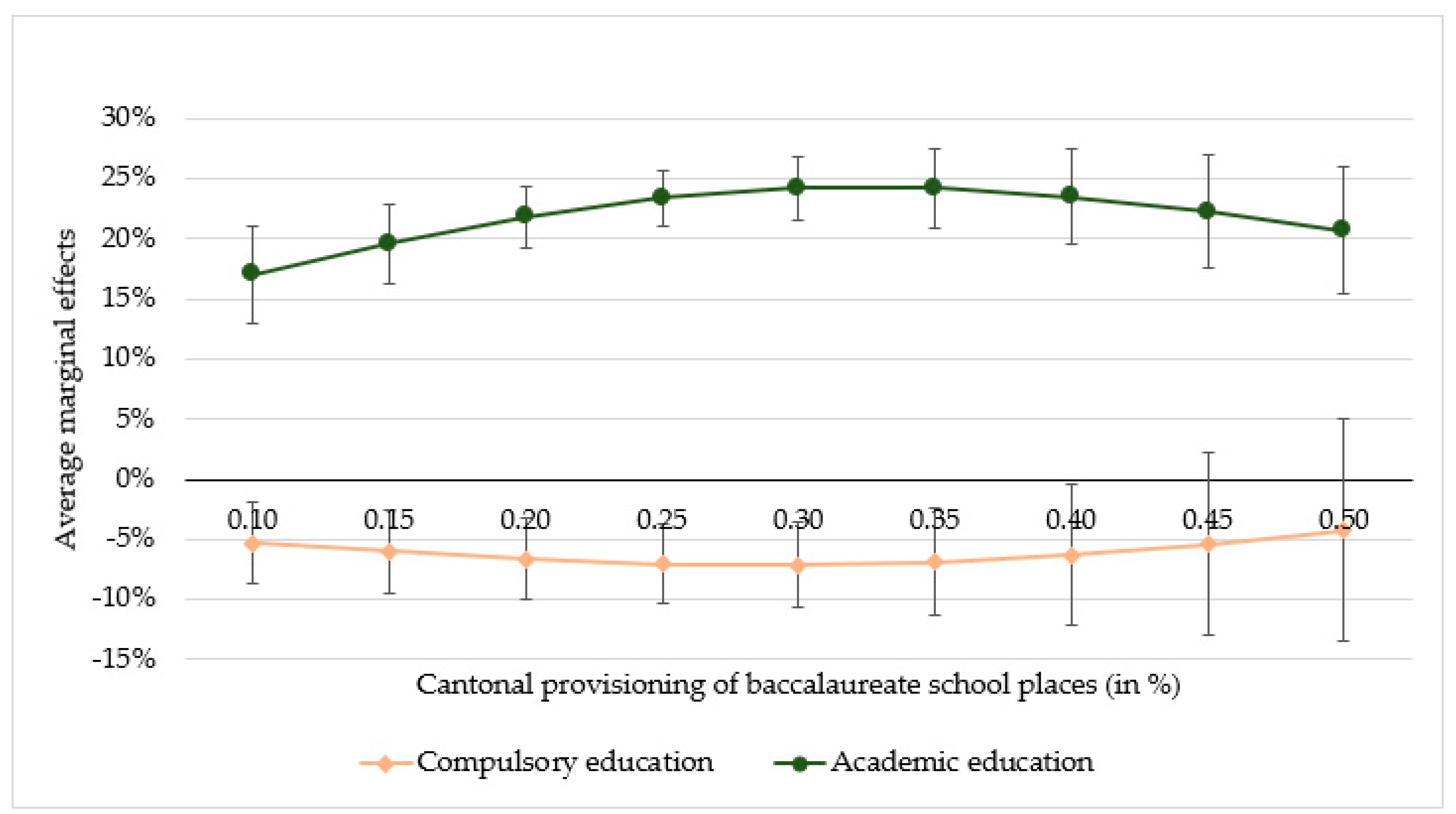

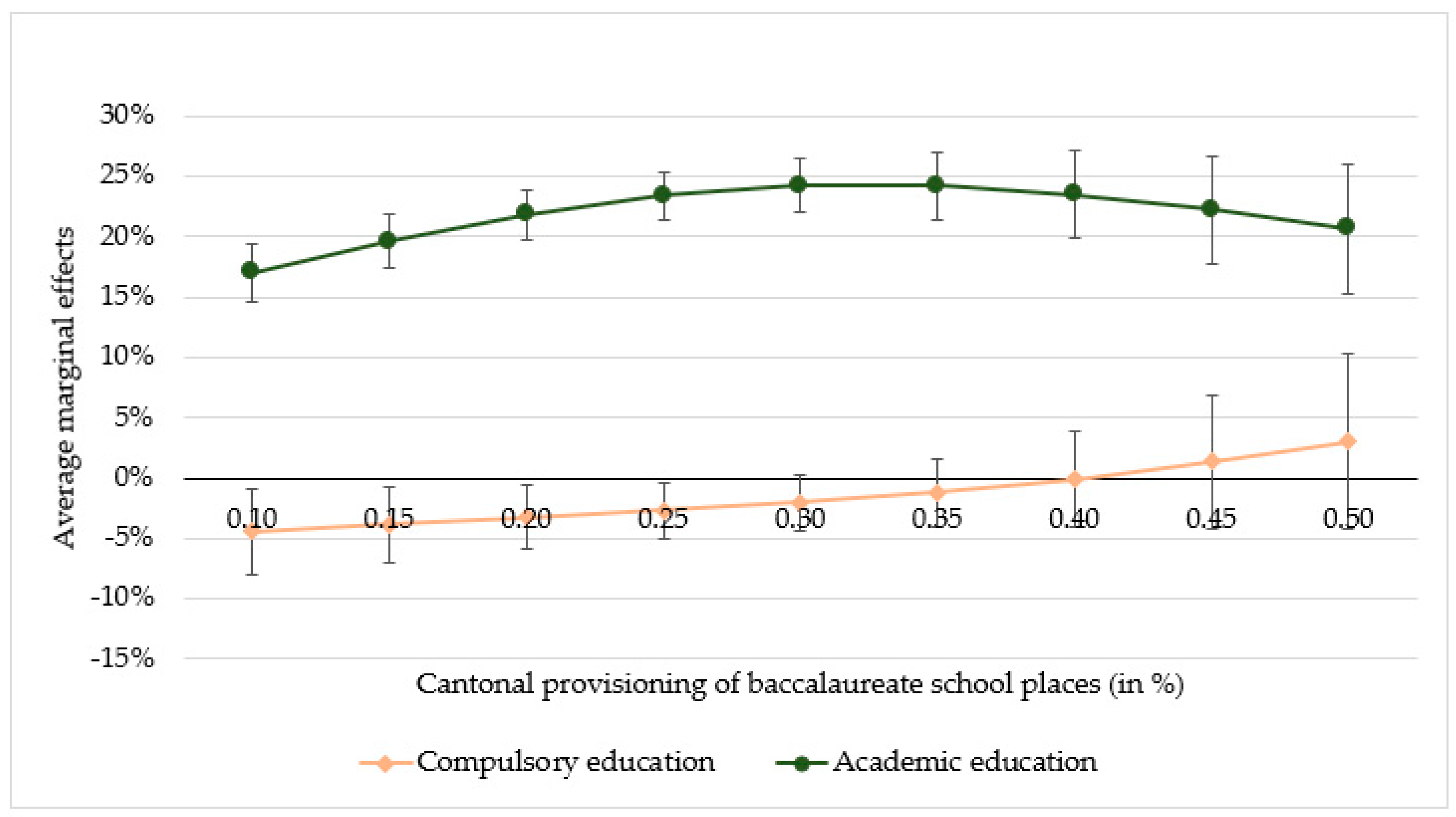

Figure 3 (model 1) and

Figure 4 (model 2) show how the probability of all three groups (academic education = green dots, intermediate education = blue triangle, and compulsory education = orange rhombus) depends on the cantonal provisioning of places. It increases for all groups as the cantonal provisioning of baccalaureate school places increases (Hypothesis H1).

Figure 5 (model 1) and

Figure 6 (model 2) show that the probability does not increase equally for all groups, although the interaction effects in the models are not significant (see

Table A4 and

Table A5). However, with the plots of the PM and AME including confidence intervals, it can be shown at what proportion of the cantonal provisioning of baccalaureate school places significant differences exist between the groups with different familial educational backgrounds.

If we look first at the pupils from academic families, there is some evidence that they benefit more from an expansion of places at baccalaureate school than the two other social groups. The differences between the average marginal effects increase slightly between the socially privileged group of academic offspring (green dots) and the two other social groups as the availability of places increases (i.e., inequality in access is growing). The observed scissors effect decreases when the availability of places is at 30% to 40% and above. And so does inequality of access. At this reversal point, the inequality in model 1 is nearly 20 percentage points and in model 2, it is over 10 percentage points.

The picture is different when comparing pupils with the intermediate (zero-line) to the pupils with the lowest family educational background in model 1 (orange rhombus in

Figure 5). Here, we can see that their probabilities of attending baccalaureate school differ significantly but only slightly to the advantage of the first group, up to an availability of about 40% of places at baccalaureate school. At higher percentages, the confidence intervals overlap (i.e., there is no longer a statistically significant difference between the two groups). In other words, there are no longer inequalities in opportunities of access between the two social groups. Model 2 even shows no significant difference between the two groups for all types of cantonal provisioning of baccalaureate school places (

Figure 6).

We can thus conclude that the probabilities of access between these two social groups differ little or not at all, regardless of the supply of places at baccalaureate school. There is evidence from model 1 that a very high percentage of places, as we find in the cantons Ticino (41%) and Geneva (47%) (see

Table A6 in

Appendix A), eliminates any inequalities.

Contrary to our assumption in Hypothesis H6 that the probability of access for the less privileged pupils improves as the number of places increases, the relationship turns out to be curvilinear. Inequality between the most privileged group—pupils from academically educated parents—and the other two groups first increases as the supply of places rises but then starts to decrease again at around 30% to 40%. However, there is no statistical evidence that inequality would be significantly smaller with a very large supply of places compared to a very small supply. Moreover, the range of the confidence interval (i.e., the uncertainty as to where the true value lies exactly) increases as the number of places increases because there are fewer cantons in the upper range.

Furthermore, an individual’s probability of attending baccalaureate school does not differ substantially between pupils with parents who completed their education with no more than compulsory schooling and pupils with parents who completed an upper-secondary level or tertiary level education.

5.5. Possible Explanations for the Interplay between Social Origin and Cantonal Structures of Educational Provision in Access to Baccalaureate School

How might we explain the slightly convex relationship that we observed between the provision of places at baccalaureate school and the degree of inequality between the three social groups? With three different situations in mind, we could refine our initial hypothesis that the probability of access for lesser privileged pupils improves as the number of places increases. In cantons with very limited numbers of places at baccalaureate school (e.g., Glarus at 14%), strong competition exists [

9,

30]. As a consequence, we assume that only some of the pupils from the most privileged social group succeed in moving on to baccalaureate school. In cantons with a higher availability of baccalaureate school places (e.g., Zug at 25%, Neuchâtel at 29%), we suppose that the pupils from the most privileged social group who previously had no chance of attending baccalaureate school in cantons with limited availability are now succeeding in gaining access. Nevertheless, competition would persist and make it difficult for pupils from lower social classes to enroll. Because a larger proportion of pupils from the most privileged social group would manage to enroll in baccalaureate schools, inequality would increase. This would be in line with the results of Sixt for Germany [

20].

In cases where there is greater availability of baccalaureate school places, such as in the canton of Basle City (36%) or Geneva (47%), we suppose that the demand of the most privileged families for places at baccalaureate school has reached saturation. In this situation, competition would be moderate, and pupils from less privileged families would have better chances to enroll in a baccalaureate school. Inequality would correspondingly decrease. This phenomenon is in line with the theory of maximally maintained inequalities, which holds that “transition rates and odds ratios between social origins and educational transitions remain the same from cohort to cohort unless they are forced to change by increasing enrollments […] If the demand for a given level of education is saturated for the upper classes, […] then the odds-ratios decrease (the association between social origin and education is weakened)” [

67] (p. 56f). The authors of this text are referring to the phenomenon of uneven development of transitions to high school for different social groups among historical cohorts in the context of educational expansion. Applying the theory to our area of research means that we assume that inequality in the probability of entering baccalaureate school among the upper and lower social classes will persist until such demand is saturated among the upper classes. After this saturation point, we can expect inequality between the pupils from academically educated families and the two other groups to decrease. (We would like to thank one of the anonymous reviewers for this helpful advice.)

The fact that there are pronounced differences in access opportunities between the group of pupils with an academic family background and the other two social groups, yet only small differences between the latter, supports the thesis that baccalaureate school serves mainly as a place of social reproduction of the most privileged class.

6. Summary and Discussion

In this paper, we focused on the transition from compulsory education to baccalaureate school in the Swiss federally organized educational system. Baccalaureate school is the most demanding track in terms of academic performance and can be considered the royal road to universities. The pronounced autonomy of the 26 Swiss cantons in educational policy and their delegation of legislative and administrative tasks to municipalities give rise to substantial variance in institutional conditions at the cantonal and municipal levels. When looking at the cantonal transition rates to baccalaureate school, we see an impressive variance, with the lowest proportion being 13% and the highest over 50%. Such large differences cannot be explained solely by cantonal differences in pupils’ academic performance. Instead, we suggest these variances are the result of different educational and socio-spatial structures. In addition to this regional inequality, social inequality also exists in baccalaureate school attendance. Pupils from socially privileged families attend baccalaureate school more often than pupils from socially disadvantaged backgrounds. However, whether this inequality varies between the cantons has not yet been comprehensively investigated.

The aim of this paper was twofold. First, by drawing on national longitudinal register data, we investigated how institutional conditions at the cantonal and municipal levels impact access to baccalaureate school (regional inequalities). Second, we analyzed whether inequality of access between different groups of social origin changes depending on one of these conditions, namely, on the cantonal availability of places at baccalaureate school (social inequalities).

Our results point to three central findings. First, with regard to regional inequalities, while controlling for the individually completed track at the lower-secondary level and the sociodemographic factors of gender, social origin, migration background, and age, we were able to demonstrate that institutional conditions at the cantonal and municipal levels structure the probability of transition. The greater the provision of places at baccalaureate school in a canton, the better the chances for pupils in gaining access. Aspirations for baccalaureate school are usually more widespread than the available places in a canton. As the availability of those places increases, more pupils have the opportunity to transition to baccalaureate school.

On the municipal level, the urbanization of a municipality, the proportion of pupils in the different tracks of varying requirements, and the social composition of the pupil body are relevant factors that impact the pupils’ chances of entering baccalaureate school. Living in an urban community encourages the transition to baccalaureate school, as the supply of apprenticeship places as an alternative educational path is probably lower, and the demand for academic jobs is likely higher. There are indications that a higher municipal proportion of pupils in the track with basic requirements leads to a smaller probability that individual pupils will transition to baccalaureate school because the value placed on the vocational path is greater. In the same vein, a higher proportion of pupils in tracks without differentiation between levels increases their individual probability of entering baccalaureate school, because the likelihood also increases that they will be assigned to this track that allows for a higher educational permeability.

As for the social composition of the body of pupils, our findings substantiate that in communities with many well-educated parents, the probability increases that an individual pupil will enter baccalaureate school. We explain this finding on the grounds of how a neighborhood of this kind might influence the way parents familiarize themselves with academic education and calculate the costs and risks of an academic pathway [

59]. In such a neighborhood, attending baccalaureate school becomes the norm and a reasonable option for the less educated families as well. We can conclude that in municipalities with a high proportion of academically educated parents, children often attend the pre-baccalaureate school, and as a result of this earlier transition, this municipal effect is already absorbed into the fourth category of our variable of the lower-secondary track. Descriptive analyses of the social origin of the pupils in the two tracks with advanced requirements confirm this assumption. In 42% of the cases, pupils in the pre-baccalaureate track originate from an academically educated family, whereas this percentage is only 19% for pupils in the general track with advanced requirements. Our results also suggest that it is precisely in these municipalities that a very large number of pupils with an academic family background access the pre-baccalaureate track at the lower-secondary level. Therefore, they effectively no longer have to succeed in a transition; they have only to be promoted.

Second, with regard to social inequalities, the degree of inequality between the group of pupils with the intermediate and lowest family educational background is very small and often not significant, irrespective of the number of available places at baccalaureate school in a canton. By contrast, inequality between the group of the highest (i.e., academic) family educational background and the two other groups is substantial and significant, which supports the thesis that baccalaureate school serves mainly as a place of social reproduction of the most privileged class.

Third, this inequality between pupils from academically educated families and pupils from less educated families varies in a nonlinear relationship, depending on the supply of places at baccalaureate school. Contrary to the hypothesis that more available places at baccalaureate school reduce inequality as a result of reduced competition between social classes, we found that with an increasing cantonal supply of places, the already socially privileged pupils benefit even more, and inequality between pupils from academically educated families and other social groups widens (the scissors effect). We can explain this by the fact that the academic aspirations of the parents with an academic background are not yet saturated. As they possess more resources to support their children than parents of a lower social origin, the probability increases that their children will be able to enter baccalaureate school. Only when the availability of places is around 35% does the demand of these families become saturated, which is in line with the theory of maximally maintained inequality [

67]. In cantons beyond this reversal point, the probabilities of access among the three social groups converge to some extent. However, there is no statistical evidence that inequality would be significantly smaller with a very large supply of places compared to a very small supply.

In light of the recurrent debate in educational politics and media on the matter of

regional inequalities in access to baccalaureate school, our study shows that institutional conditions at the cantonal and municipal levels, conceptualized as regulative, normative, and cultural–cognitive pillars [

31], frame and structure individual motivations, aspirations, opportunities, decisions, and actions with regard to attending baccalaureate school. These institutional conditions relate directly to the education system (structures, offers, and regulations), to social, housing, and labor-market policies, as well as to strongly rooted cultural values and norms regarding academic education.

In view of political and scientific discussions on

social inequalities and their policy implications, our findings indicate that simply increasing the number of places at baccalaureate school does not simultaneously reduce inequality. Of course, more pupils do gain access, and this does include those from disadvantaged backgrounds. However, in the competition over access, the privileged social classes benefit even more from the increase in available places. However, this should not necessarily lead to the conclusion that the number of places should not be increased. If politicians want more pupils entering university education as a response to a larger skills shortage [

21], this is one possible way, and one that also opens up this pathway to disadvantaged social classes.

However, the methodological limitations of this study must also be considered. The first is the fact that data from 26 of the cantons did not allow for the computation of multilevel statistical analyses (MLA), which would be the more appropriate statistical procedure. It should nevertheless be noted that previous attempts to calculate MLA for model 1 based on an auxiliary construct for social origin for the entire population, which were criticized from a methodological standpoint in an earlier version of this paper, have led to similar results. Both individual and regional factors influence entry into baccalaureate school in similar ways, and a curvilinear relationship between the cantonal provision of baccalaureate school places and social origin has also been demonstrated.

A second limitation arises out of the impossibility of controlling for pupils’ achieved competences in math and language upon their completion of lower-secondary education. Be that as it may, it is not reasonable to expect large differences between cantons in pupils’ academic potential, and furthermore, we controlled for the track of lower-secondary education as well as for social origin. We therefore characterize these two stated limitations as minor.