1. Introduction

Positive psychology is a branch of psychology that studies optimal human functioning from a scientific basis [

1]. This trend, driven by Seligman, promotes research and the fostering of the positive aspects of the human being as the basis for happiness.

Seligman bases his study on three pillars: positive emotions; positive traits, which are personal virtues and strengths; positive institutions, which should facilitate the development of the other two pillars. Furthermore, he proposes two premises as foundations: that cultivating virtues and strengths will make us happy and that a happy life is a pleasant life, but one that must have meaning [

2].

Research on personal strengths within positive psychology materializes in trait theory. Seligman refers to good character as that which is constituted by positive traits, which he calls strengths.

The distinctive qualities that, according to Seligman [

2] and Park and Peterson [

3], this good character should comprise a family of positive traits that are manifested in individual differences and that allow the strengths that people possess to be distinguished. These traits are manifested through thoughts, feelings and actions; can change throughout life; are measurable and are influenced by contextual, proximate and distal factors, so that character and its strengths are educable.

The six universally accepted positive traits, which are also called virtues, are wisdom, courage, humanity, justice, moderation and transcendence. As these virtues are very general and abstract, but are concretized through 24 personal strengths, which are defined as morally valuable styles of thinking, feeling and acting, which contribute to a life in fullness [

4].

Seligman [

2] differentiates three aspects that are present in the concept of happiness: pleasure, commitment and meaning. For people to be happy, they must guide their lives towards the balance of these three aspects, especially the last two [

5,

6]. Subsequently, he added two more aspects to this model of well-being, achievements and interpersonal relationships, to create the PERMA model [

7] of positive emotions, engagement, relationships, meaning and achievements. These aspects give happiness an internal and social nature.

Happiness, in the scientific approach of positive psychology, is considered “subjective well-being”, which includes two components: the emotional and the cognitive [

8].

Happiness or well-being and personal improvement are inseparable processes. Seligman [

2,

7] states that to be happy, we need to develop personal strengths and capacities with which to enjoy things and achieve the necessary balance and satisfaction in life. Fordyce [

9] was the first to develop a project for teaching happiness; based on the scientific literature, he recognized 14 qualities associated with happiness.

We present the counts and definitions of the virtues and character strengths, according to Seligman and Peterson (

Table 1):

Positive psychology encourages education professionals to become better able to help people increase their well-being and flourish. This translates into improving people’s quality of life and subjective well-being and developing their competencies [

10]. According to this author, common elements of positive psychology, such as well-being and the development of strengths, among others, should be integrated into the mandatory academic curriculum.

Different programmes and experiences of positive psychology are applied in education, such as “Bounce Back!” [

11]; the “Celebrating Strengths Programme” [

12]; “Strengths Gym” [

13]; the “Affinities Programme” or “Strong Planet” [

14] and “SMART Strengths” [

15] in the United States and the “Programa de promoción del desarrollo personal y social” [

16,

17], the “VIP Programme” [

18] and the Handbook of Positive Psychology in Schools [

19] in Spain.

We opted to apply the Peterson and Seligman model of happiness to education in our research because it is a global model, with important theoretical and empirical support, and because it can be applied in the educational field. Positive education is born of positive psychology’s study of the optimal functioning of the human being in educational contexts [

20]. It is supported by research on emotions in teaching and learning processes [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26].

Because it is practically impossible to develop all of a student’s strengths, as many characteristics as possible should be improved, as should others that are less innate, when possible. As indicated by Reivich et al. [

27] and Seligman [

2], by improving personal qualities and skills and social contexts through the fostering of resilience and well-being, character strengths are cultivated, and positive emotions and relationships are experienced.

Education in the arts seeks to encourage the student’s autonomy in their learning process and connect them with the world through its affective and cognitive components [

28]. Its affective component makes the arts different from scientific thought and its influence on curricula, thereby adding value to general education. In addition, a work of art in itself can evoke perplexity, mystery or confusion that creates enormous cognitive demand and encourages intellectual research [

29].

There is a body of literature that links the arts in education with positive psychology, demonstrating that it develops fundamental strengths for achieving eudaemonic happiness and subjective well-being [

30,

31]. There are countless antecedents of studies of artistic projects that seek eudaemonic happiness and the well-being of their participants, such as the Sing Up Programme in the United Kingdom [

32] and studies in educational centres in Canada [

33], in youth orchestras in Argentina [

34] and in the Venezuelan system and the projects it has inspired [

35,

36].

We, thus, recognize a confluence of positive education with emotional education in the arts that contributes to the personal and social well-being of the individual and develops students’ integral personalities, enabling them to face daily challenges by working with values [

37]. Additionally, training autonomous individuals who can adapt to the changes and needs of the new labour market has led to concerns about education at the international level. This is how the OECD came to create the DeSeCo project [

38]. In this project, school curricula are reformulated around the concept of competencies. A series of Key Competencies are created that serve as a reference for the educational systems of the member countries and through which the individual is responsible for his or her learning, moving from being a consumer of knowledge to a builder of it, a process that strengthens students’ overall development [

39].

To clarify this relationship, the Key Competencies of the European Union and the character strengths that could be included in and/or developed through them are compared (

Table 2).

Research, such as that of Miller, Dumford and Johnson [

40], provides evidence that the arts are fundamental and foster the acquisition of professional competencies that students will use in their day-to-day lives and that are necessary in social settings.

The connection between emotion and attention is vital, and it seems that art is one of the most reliable and interesting methods for developing competencies, since it has been demonstrated that there is a relationship between attention and the emotional world [

41].

In a previous mapping, we observed that there are already systematic reviews dedicated to three coexisting competencies: social and personal, professional and methodological [

42]. There are also two meta-analyses that cover the areas of social and emotional competencies, but none that relate competencies with all of the strengths in the field of arts education [

43,

44].

At this point, we intend, through this literature review, to demonstrate the relationship between the Key Competencies as catalysts for the development of character strengths in students through art programmes in education.

2. Systematic Review Methodology

A systematic review of the literature was developed for which we used the PRISMA model as a framework [

45], adapting the checklists of the CASP model [

46] in the Web of Science (WOS) and Education Resources Information Center (ERIC) databases.

Before carrying out the systematic review, we verified the validity of these models by performing a search in WOS with the terms Review, PRISMA, CASP and Education for the last 5 years. We obtained articles such as the study by Gow, Mostert, and Dreyer [

47] that legitimize the use of CASP in the PRISMA model for our systematic review using the WOS and ERIC databases.

2.1. Identification. Search Terms

To identify the search terms, we used the PICo criteria [

48] on the basis of their reliability, as determined by keyword searches based on the PICo elements: participants, interventions and comparators.

Participants: Children, youth and adult students in primary, secondary and university education in formal, nonformal and informal education fields and in settings with low, medium and high social involvement.

Intervention:

- ⚬

Arts in education studies linked to character strengths.

- ⚬

Positive education studies related to the arts in education.

- ⚬

Studies of the relationship between the Key Competencies and an operational breakdown of the character strengths of positive education in the context of the arts.

Comparators: In terms of the search, we considered alternative interventions that contextualized the search within positive education in the arts.

To organize our search, we classified the terms in relation to four constructs: positive psychology, education, arts and the Key Competencies.

For each construct, we considered the following search terms: Positive psychology (Character Strengths, Values in Action, Positive Psychology, Eudaemonic Happiness, Happiness, Wellbeing, Well-being, Eudaemonic Wellbeing and Wellness), education (Education and Positive Education), Arts (Arts, Arts-Based Education, Education through Arts, Arts Education, Artistic Education, Arts in Education and Arts-Based Programmes) and the Key Competencies (Competencies, Skills, Key Competencies, Educational Competencies, Emotional Competencies, Social Competencies, Cognitive Competencies and Basic Skills). Each of the search terms included in these constructs was combined with the others.

By combining the nine terms related to positive psychology, the two terms related to education, the seven terms related to the construct of arts in the educational context and the eight search terms related to the Key Competencies, we performed a total of 1,008 searches in each database (WOS and ERIC) using the Boolean operator AND.

The result of these searches was 50 articles in the WOS database and 48 references in ERIC, of which 43 were articles and five were books.

Each article was coded to obtain information on the type of sample. An ID was assigned to each article with the letter W or E, depending on the database where the article was found (WOS or ERIC, respectively).

This screening required a subsequent analysis of the potential synonyms and alternative terms that appeared in the included articles. In the case of the constructs “character Strengths” and “key Competencies”, they are not always studied explicitly, but implicitly.

Although the explicit treatment of the constructs in the articles is preferable to the implicit treatment, the interpretation of the implicit concept lies in the relationship and how it is defined by the reader [

49].

It is interesting to analyse how the terms used in the different articles describe the constructs that are the object of our study, that is, how researchers have referred to the constructs to define them or to specify the relationships among them.

To this end, we present the theory of Murphy and Alexander [

49] regarding the explicit or implicit definitions of the construct through the terms used by the authors of the articles. This multiplicity of terminology used to define the constructs, citing Murphy and Woods [

50], occurs because lexicons are developed as the members of a certain community label and define constructs.

The way that constructs are labelled or named is fundamental for the development of theories, which must be clarified to create a perfect definition of both the constructs and the terms that define them.

In the case of the social sciences, specifically education, as expressed by Dinsmore, Alexander and Loughlin [

51] citing Alexander, Schallert and Hare [

52] and Murphy and Alexander [

49], there is a lack of clarity and linguistic specificity in educational literature, where lexicons can be amorphous and open to interpretations that can lead to a misinterpretation of the construct. This can, as the authors explain, be the result of wanting to use terms with the expectation that their meanings are well known and accepted or without considering the thoughts underlying them or the understandings that have resulted from their imprecise use.

In our research, we observed that, because neither positive psychology nor the Key Competencies have a very extensive trajectory, professionals from different fields of research have contributed to these trends in psychology and education by borrowing terms and findings from their respective fields of research, introducing related terminologies that can lead to ambiguities when defining a construct.

2.2. Screening

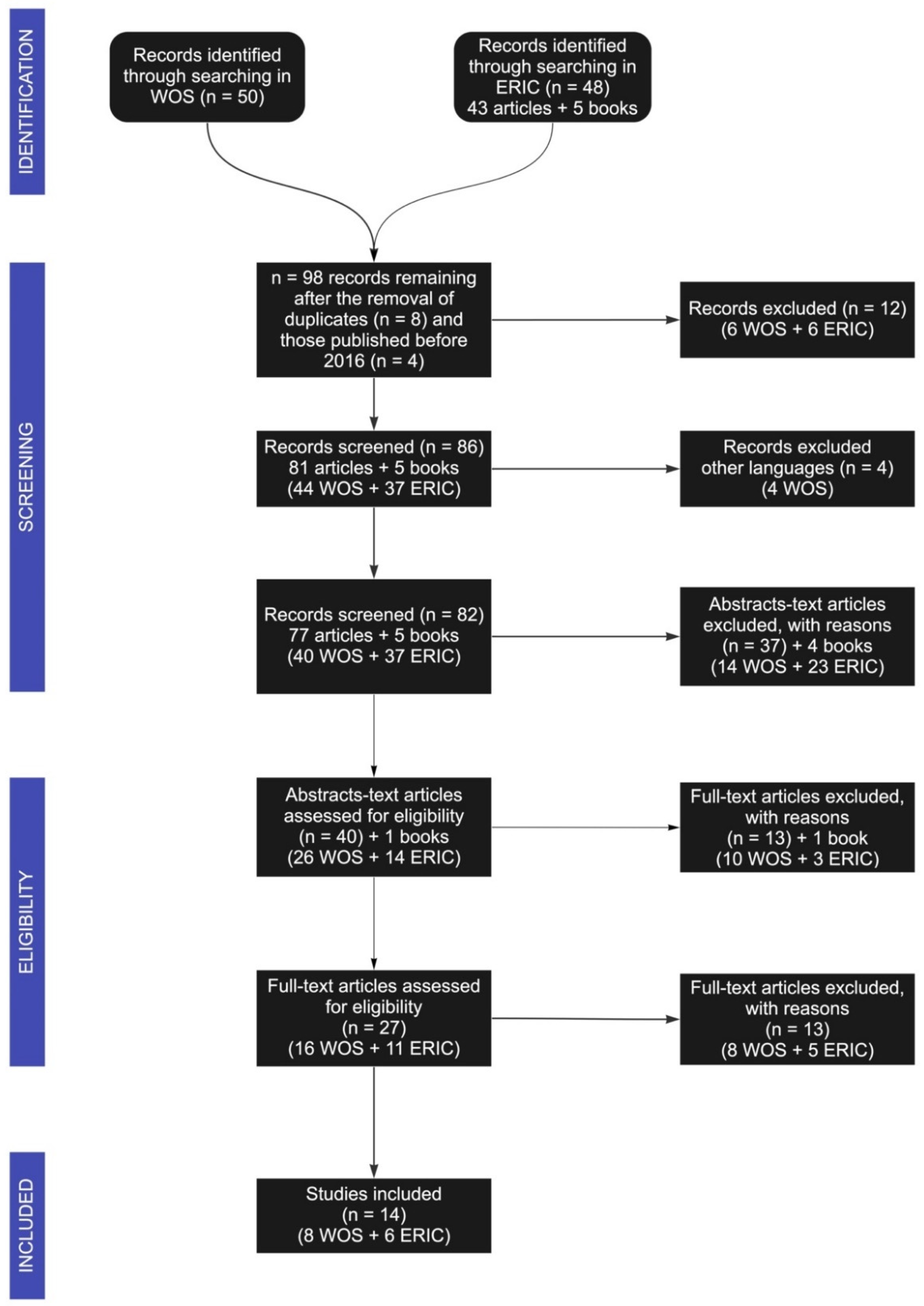

Before the exclusion and inclusion criteria were applied, articles that were duplicates (n = 8) or were written before 2016 (n = 4) were eliminated using Microsoft Excel software. Of the 98 initial references, 86 remained.

2.3. Eligibility

2.3.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria

Pragmatic criteria:

- ⚬

Languages: English and Spanish.

- ⚬

Studies in student population among children, youth and adults.

- ⚬

That the research of the articles be carried out in the formal school environment (Primary and Secondary or in the equivalent of other countries), university, adult training and in non-formal and informal environments.

- ⚬

Publication date: Articles published after 2016.

- ⚬

Publication type: Paper, journal articles, indexed articles, book chapters indexed or not in Scholarly Publishers Indicators (SPI).

Quality criteria:

- ⚬

Reference databases: WOS, ERIC.

- ⚬

Journals from quartile 1 to 4. As well as non-indexed journals of authors of relevant prestige. Book articles and congress communications.

- ⚬

That the objectives of the studies of the selected articles are in line with the objectives of our research.

Exclusion criteria

- ⚬

Duplicate articles.

- ⚬

Population whose educational context is too informal, and its population is the teaching staff.

- ⚬

That the research of the articles has been carried out with a child or very young population.

- ⚬

The population did not include both genders.

- ⚬

Articles published before 2016.

- ⚬

Articles that are indexed in reference databases other than WOS and ERIC.

- ⚬

Bachelor’s theses, Master’s degree and doctoral theses.

- ⚬

That the objectives of the studies of the selected articles were not in line with the objectives of our research.

2.3.2. Review Phases. Traceability

We applied the inclusion and exclusion criteria in four phases:

Studies in languages other than English or Spanish were excluded (n = 4). Of the 86 references, 82 remained; 40 were identified in WOS, and 37 were identified in ERIC, of which 32 were articles, and five were books.

We proceeded to read the abstract. During this process, we screened the studies that were directly related to the four constructs under study. During this step, 37 articles and four books were eliminated. The remaining references continued to the next screening step (26 were from WOS and 14 from ERIC, of which 13 were articles, and one was a book).

We read the full text of the 37 references, of which one was a systematic review that we have included for its investigative value. To ensure the eligibility of the included references, we applied the CASP checklist to each selected article and to the different stages of our systematic review.

Eight articles and one book were eliminated because they did not address the relationship among the four constructs, leaving 27 articles, of which 16 were found in WOS, and 11 were found in ERIC.

In this last phase, which initially included the 27 references that were related to the four study constructs, 14 references obtained conclusions that answered our research question; eight were selected from WOS, and six were selected from ERIC. The remaining 13 articles (eight from WOS and five from ERIC) partially answered our question. Therefore, our study and analysis of the results focused on the first group of 14 articles. We present a summary of the selected articles included in our systematic review with their IDs, title, authors, year of publication, type of document, journal or book, where the study was published, in addition to the age, gender and educational level of the participants, the research methodology and source of data for the paper (

Table 3).

2.4. Included

Below, we outline the different steps of our systematic review (

Figure 1):

3. Results

The results that we present confirm the relationship between the Key Competencies and the development of character strengths in students through art programmes in education.

In global terms, the Key Competencies have been linked to character strengths, although the terminology used by researchers has not always been explicit.

The explicitly clear constructs that appeared in the selected articles were “Art” and “Education”. That is, it was clear that all of the articles were based on artistic projects in the educational setting, whether formal, informal or nonformal.

3.1. The Arts Object of Study

Regarding the types of art on which the studies focused, we found that there were mainly four types. The first (

n = 6) was workshops and generic art programmes and art-based methods; in these cases, the studies covered different contents. The second type was the performing arts (

n = 4), and the third was storytelling (

n = 3). The last (

n = 2) was visual arts. It is noteworthy that W24 focused on both the performing and visual arts (

Table 4).

3.2. The Areas of Education under Study

Regarding the educational settings where the research was carried out,

Table 2 shows that in most cases, the studies were developed in a formal education setting (

n = 9), followed by nonformal (

n = 5) and informal settings (

n = 3). It is noteworthy that W47, E24 and E42 were developed in more than one learning environment (

Table 5).

3.3. Virtues and Character Strengths

The definitions of character strengths and Key Competencies constructs required the most detailed analyses of the different terms that the authors used in their articles.

To ensure that our search terms were not overly restrictive and were not the only terms that the authors used to refer to or define our constructs of interest, we analysed all synonymous terms and those from other social sciences that were used by researchers in the articles included in our systematic review.

For this purpose, we mapped each of the selected articles and a table of each term that the researchers used in the articles. To understand the definitions of the constructs and the links among them from the terms that the authors used in their articles and that were synonymous with our search terms, we defined the relationships among constructs explicitly (E) or implicitly (I), following the guidelines of Dinsmore, Alexander and Loughlin [

51], as described in Murphy and Alexander [

53].

The 24 strengths, as explained in the theoretical framework, are included within the six virtues that Seligman and Peterson developed in their various publications. In the articles of our systematic review, they appear in relation to the different terms used by the authors (

Table 6).

We see that there are virtues that were related to certain terms in an isolated manner and virtues that are in combination with others, in relation to a term that the author used.

This table shows that Virtue 1 (wisdom and knowledge) was described with the highest number of terms, with 48, followed by Virtue 3 (humanity), with 44 terms. It is important to highlight the ability to associate each of the virtues with the terms used by the researchers in the articles in our systematic review.

As Seligman and Peterson state, these virtues are represented by strengths, which are related to the terms used by the authors of the articles (

Table 7):

From

Table 7, we can deduce that there are strengths that were described with a high number of terms in the articles. Strength 12 (social intelligence, personal intelligence, emotional intelligence) was described with the highest number of terms, 36, in the articles, followed by Strength 13 (citizenship, social responsibility, loyalty, teamwork), with 33 terms, and Strength 3 (open-mindedness, judgement, critical thinking), with 26 terms.

Table 7 shows that Strengths 1, 3, 12 and 13 were the most frequently referenced in the selected articles. Ranking second, with more than 10 citations each, are Strengths 2 (love of learning), 4 (creativity, originality, practical intelligence, insight), 5 (perspective), 10 (kindness, generosity, compassion, altruistic love, kindness, care), 20 (appreciation of beauty and excellence) and 24 (hope, optimism, foresight). The other Strengths were also referenced in the studies, but had fewer than 10 mentions.

We must highlight the limited mention of Strengths 6 (courage) and 14 (impartiality and equity) in the articles; each of these strengths were cited using only one term.

Table 8 shows that when the terms used could be related to more than one strength, Strengths 12, 13 and 3 continued to predominate, but Strength 1 (curiosity, openness to experience, interest in the world) acquired a greater presence in regard to the number of terms used.

It is also interesting to observe how the different strengths here combined in the articles through the selected terms.

As the previous table shows, some of the terms that the authors used could refer to a significant number of strengths.

3.4. Key Competencies

Similarly, we analysed the terms used in the selected articles to reference the Key Competencies (

Table 9).

We observe that there are unique competencies associated with some terms in the articles. The competencies for the highest number of terms used were Competency 5 (learning to learn), with eight terms, followed by Competency 6 (social and civic competencies), with four terms.

When terms could relate to more than one competency, Competencies 5 and 6 were still present, but Competency 7 (sense of initiative and entrepreneurial spirit), with 88 terms, and Competency 8 (cultural awareness and expression), with 84, acquired greater strength. We must highlight Competency 2 (communication in a foreign language), which was alluded to 69 times, as a competency that was closely related to the terms used in the articles.

Competencies 2, 5, 6, 7 and 8 were the ones that were the most frequently referenced by the selected articles, while by Competencies 1 (communication in the native language), 3 (mathematical competence and basic competencies in science and technology) and 4 (digital competence) were the least frequently referenced in the articles included in our systematic review.

It is also interesting to observe how the different competencies were combined in the articles through the selected terms. As

Table 10 shows, there were five combinations of Key Competencies that contained more than 10 terms. These combinations also contained all of the competencies in similar proportions.

3.5. Linking Character Strengths and Key Competencies

Regarding the character strengths and competencies, most articles referred to them using implicit rather than explicit terms (

Table 11).

We must highlight the significant number of terms used by the authors that were synonymous with character strengths and the Key Competencies but were not used explicitly in the articles.

To determine how the Key Competencies of the European Union and Seligman and Peterson’s character strengths are linked, and the nature of those links, we created

Table 12, in which the red boxes indicate the only instances in which the Key Competencies and character strengths do not overlap in the terms used by the authors of the articles selected for our systematic review.

From

Table 12, we can see that Strengths 6 (courage), 7 (persistence, industry, perseverance), 9 (vitality, enthusiasm, energy, passion, zest) and 19 (self-control) had the least overlap with the Key Competencies.

The rest of the competencies and strengths, whether explicit or implicit, share the terms used in the article to convey their meaning.

4. Discussion

After the analysis and interpretation of the articles included, we must remember that our main objective was to conduct a systematic review of the existing literature to discover if there was a link, and of what nature, between the character strengths and the Key Competencies of the arts in education.

The results demonstrate this connection, although we emphasize that the investigations carried out to date, in most cases, define and link some of the constructs implicitly through different terms. A more explicit view of the four constructs will be necessary when studying and defining the relationship between these constructs in the future, especially when examining the relationship between the constructs of the character strengths and the Key Competencies.

After the analysis was carried out, we highlighted the abundant terminology and synonyms to define each construct, depending on the field of study of each researcher. This terminology fosters confusion that would need to be corrected to facilitate research, deepening and linking the different areas of knowledge. The arts, education, positive psychology and lifelong learning for key competencies define the same construct with different perspectives and terms that we have had to trace.

We, therefore, consider that our results are valid and reliable; however, only with this global vision can we achieve a totally explicit link and avoid possible interpretations of inter-construct relationships that are left to the discretion of the reader.

Given that, in our previous mapping, we emphasized that there are no other systematic reviews that relate competencies with strengths in the area of arts in education and that allow us to compare our results with those of similar studies, we cannot know whether our results are similar to those of other reviews. The reviews that were found studied and analysed the relationship between some of our constructs, but not the relationship between them and the Key Competencies.

We highlight the general interest of the literature in this field of education, but we must also point out the lack of articles that explicitly link the constructs that are the object of our study. Thus, our research could lead to an interesting field of study and research, focusing on labelling or determining in an explicit and concrete way the character strengths that are part of a given competency.

Our analysis of the components of the Key Competencies, from the perspective of character strengths, could represent an important field of research in the contribution of positive education to competencies and the contributions of the field of education and education competencies towards character strengths.

These future investigations will help teachers to apply and more clearly understand the Key Competencies and create tools to execute them in the classroom, enhancing and developing students’ strengths.

These implicit links, with which we have connected the Key Competencies and the character strengths, in the area of the arts in education, are a first step in seeking more explicit links between the two. Future studies should focus on educational projects in the arts that realize the development of strengths connected to the Key Competencies, as an educational model, based on students’ happiness and well-being that, at the same time, encourages improvement in educational quality and in the academic and competence outcomes of future professionals.

5. Conclusions

In view of the results of our SR, we can conclude that a relationship between Key Competencies and the Character Strengths can be defined, as well as outlining the nature of these relationships.

In the analyzed studies, we have found that certain patterns of combinations of strengths were repeated in the Key Competencies.

We emphasize that we have not found any previously published work in the same direction as our research and with which we can compare our results.

The mechanism by which we have found the link between Character Strengths and Key Competencies is derived from

Table 12, as explained in the results, where we can see that there were two virtues, 1 (wisdom and knowledge) and 3 (humanity), in which all of the competencies developed by the arts in positive education employ all of the strengths that compose these two virtues.

We conclude, therefore, that through all the Key Competencies, the arts in positive education encourage the fundamental curiosity, love for learning, open-mindedness, critical thinking, creativity, originality, perspective, kindness, generosity, love, social intelligence, personal intelligence and emotional intelligence in students, who will be able to transfer them to the changing professional world.

From

Table 12, there are three other Virtues, 4 (Justice), 5 (Temperance) and 6 (Transcendence), in which not all the strengths have been linked to the Key Competencies.

With respect to Virtue 4 (justice), it was not possible to find a clear link between Competency 1 (communication in mother tongue) and Strength 14 (impartiality and equity).

For Virtue 5 (temperance), we highlight that Strength 19 (self-control) was barely linked to the Key Competencies, with the exception of Competencies 5 (learning to learn) and 7 (sense of initiative and entrepreneurial spirit).

For Virtue 6 (transcendence), no links were found between Strength 21 (spirituality, purpose, religiosity) and Competency 4 (digital competence) or between Strength 24 (hope, optimism) and Competency 3 (mathematical competence and basic competence in science and technology).

The weaker presence of the strengths associated with Virtue 2 (courage and temperance) is noteworthy. Specifically, no links were found with Strengths 6 (courage), 7 (persistence, industry) and 9 (vitality, enthusiasm). Thus, we can conclude that the competencies that can be worked on in positive education through the arts would hardly develop these strengths.

Practical and Academic Implications and Recommendations for Future Research

From a practical point of view, the conclusions from our research allow us to make decisions to start a field of research that deepens the relationship of the Arts in education, from the perspective of Positive Education and Key Competencies.

The Arts in Education becomes the tool to link Character Strengths with Key Competencies. This contribution of the Arts develops in the student the Competences and Strengths necessary to face the constant changes that are generated in the current professional panorama.

In addition, we believe that different possibilities are opened for other researchers to delve into this still little explored field, in which we consider the application of validated tools with a greater scientific nature to be very necessary.

It should be added that a significant number of articles in our systematic review point to the lack of studies that apply the scientific method with greater rigour, so that a consistent reference framework can be consolidated. This is an element that we corroborate after the analysis and interpretation of this systematic review.

Based on our study, and after demonstrating the link between Character Strengths and Key Competencies, future research may deepen this link in the educational field of the Arts, as the foundation of sustainable human development. Since the Key Competencies are the pillar that UNESCO uses for Education for Development, this human development can be better evaluated thanks to the measurement of Character Strengths.

From the academic point of view, our SR has also made it possible to integrate the existing literature that, up to now, has attempted to address separately the different constructs that are the object of our research. With our study, we have been able to bring together the four constructs in a single research object.

Even when the articles and studies of our research seem to connect the constructs separately or implicitly, we need a larger corpus of studies that brings together the four constructs to be able to demonstrate our hypothesis more solidly.

Another type of research design would also be necessary. Future studies should apply adequate designs that include both the random assignment of participants and an active control group. Such a design would allow the empirical evaluation of whether these connections are efficient and will endure.

6. Limitations and Recommendations

In our study, we observed two important limitations. The first is that the constructs of this research belong to very diverse areas, such as psychology, education and the arts, and the researchers in each of these areas define the other constructs by importing the terms used in their own fields. This results in a lack of conceptual clarity that affected the search terms used and the criteria used to establish them, since it would have been necessary to use an excessive variety of terms to conduct an exhaustive search. Following the steps of Murphy and Alexander [

53], the choice of our search terms considered the breadth and overlap of constructs to allow for a certain degree of efficiency.

We could define this limitation as a lack of specificity when defining the constructs or, in other words, the excessive number of synonyms that are attributable to a particular construct. As previously indicated by authors, such as Dinsmore, Alexander and Loughlin [

51], this may be due to two reasons:

The first is because the construct is defined by authors who are not familiar with it or who do not regard it as its own entity, or because authors define constructs using terms from their own professional field. In this way, the researcher defines characteristics and qualities inherent to the constructs that we systematized in our systematic review. This excess of terminology, which has resulted from a need for a definition that serves all specialties, led us to broaden the search terms that we used for this systematic review and to consider implicit definitions of those constructs that were studied, with or without the express desire of the researcher.

The second limitation, which is derived from the previous limitation, is the ambiguity that can be generated by the use of a given term to define a strength or a competence. That is, the breadth of interpretations and definitions of one or several strengths or competencies can be covered by a single term. This possibility of relating a concept that appears in an article with one or more strengths and/or competencies can, a priori, generate certain limitations in the search for relationships among strengths and competencies.

We are aware, on the other hand, of other limitations of our research, such as the selected languages (only English and Spanish), the omission of a bibliometric review and not having considered other databases.