1. Introduction

Adolescence is a critical period of growth and mental development. Balanced nutrition intake and dietary behaviors play an important role in healthy growth and prevention of various chronic diseases. However, the incidence of obesity is increasing in recent years [

1], which is mostly due to irregular diet structure, bad eating habits such as not eating breakfast, deficient intake of vegetables and coarse grains, and decreased physical activities [

2].

Adolescence is also a crucial period for cultivating good eating attitudes and behaviors, which depend on mastery of good food knowledge [

3]. However, there is not a special curriculum on food nutrition in primary and middle schools in China, and students can only acquire a little knowledge in science courses [

4]. Primary science curriculum standards specify that students learn the basic concepts of nutrients and energy. Secondary chemistry curriculum standards specify that students learn the function of some nutrition organic compounds (carbohydrates, starch, protein, vitamins, and so on), mineral elements (calcium, iron, zinc, and so on), and poisonous compounds in their third year in middle school. Secondary biology curriculum standards specify that students learn how nutrients are digested and absorbed in the body. The knowledge in primary school is too shallow for students and they start learn deeper content too late. Additionally, although the government has provided some documents such as “guidance outline of health education in primary and secondary schools”, the items are not quite explicit and a number of schools do not take them as key content in normal classes. Some schools, especially those in remote areas, suffer from desperate shortages of professional teachers; instead, nutrition knowledge is taught by teachers of other disciplines [

5]. The above points are all reasons why schools did not provide favorable conditions for students to master good nutrition knowledge.

In recent years, many researchers have used educational games to assist traditional teaching in order to enhance students’ interest in active learning and improve teaching effectiveness [

6]. Chen et al. investigated the time effect of cooperative games such as cards, board games, and riddles on students’ emotions of learning science and found that games helped to maintain students’ positive emotions. Another study [

7] designed a serious game in the area of nutritional knowledge to test its effect on children and discovered it was an adequate educational tool. The researchers in [

8] explored the gamification as a teaching strategy in the pandemic years and concluded that it increased students’ motivation and engagement and improved their attitudes [

9].

Among various education games, the board game has a long history, fewer adverse effects, lower development costs, and better experience. In general, it has following advantages: (1) It can improve students’ learning motivation [

10]; (2) It is easy to combine multiple disciplinary content and improving students’ interdisciplinary ability; (3) When used in multiplayers format, it can enhance students’ language performance and communication ability; (4) The physical attributes of the board game can enhance students’ sense of immersion and leave them a deeper impression of knowledge [

11].

However, although there are many board games in the market, most lack the guidance of teaching theories and are not suitable for class teaching. Some educational games designed by researchers such as chemical pokers [

12] are mainly directed at young children, which gives priority to increasing learning interest with less emphasis on subject education. In some countries such as Turkey, Australia, and New Zealand, board games have been widely developed and used in primary and middle schools with multiple themes, including not only traditional subjects but also human and science topics like planets [

13], first aid [

14], health education [

15], chemistry [

16], creative problem-solving skills [

17], and so on. Evaluation studies have been conducted by many researchers. In contrast, board games are deficient in health and food topics in China and empirical studies are few.

This research attempts to employ game-based learning theory by developing an interesting game situation and interaction mechanism to intrigue students’ intrinsic motivation. Specifically, it tries to integrate STEM elements, particularly the knowledge of chemistry and nutrition, with daily education through a board game with the purpose of helping students to learn food nutrition in a fun environment. Students are expected to have a positive change in attitude and behavior after they finish the board game. The degree of change may vary for students of different gender and weight, as previous literature has suggested that girls are more concerned about body image than boys [

18], and there was a strong relationship observed between body image dissatisfaction and body mass index (BMI) [

19]. It is assumed that students of different gender and weight will exhibit different degrees of eagerness to obtain nutrition knowledge and change dietary habits. Therefore, the research questions are as follows:

What impact will board game have on students’ nutrition knowledge, dietary attitude, and behaviors?

Are there any differences in the effects of a board game on students of different gender and BMI?

2. Materials and Methods

This study intends to integrate a board game with chemistry lectures and thus allow the adoption of a single-group pre- and post-test quasi-experimental design to find whether the students can adapt and what effect the board game will have on them in the cognitive and affective domains.

2.1. Participants

A group of 22 students (8 females and 14 males, aged 12–13, from the same class) in grade 7 of a middle school in Beijing were selected as the participants, whose profiles and body index (BMI) can be found at

Table 1.

2.2. Study Methods

The activities were carried out for 6 weeks, 1–2 times per week and 30 min per time. One day before and after the program, questionnaires were used in pre- and post-test. A month after the program, an additional test was carried out to evaluate students’ attitude and behavior. In addition, six students were randomly selected to join a semi-structured interview at the end of the program.

2.3. Study Instruments

2.3.1. The Introduction of the Board Game

This board game has 90 checks, including food check, sports check, treasure box, supermarket, hospital, testing station, food problems tasks, and so on. Students need to move their pieces along the checks in turns by throwing the dice and collect food cards or drawing task cards in certain checks. The final goal is to acquire more healthy food according to the food pyramid and standards of basic energy metabolism.

The teaching goals are as follows:

Knowledge: understanding and mastering the relationship between seven nutrients and food, nutrient function, nutrient deficiency, food safety, food pyramid, healthy diet structure, unhealthy dietary habits, and food labels;

Attitude: recognizing the importance of healthy diet, increasing self-efficacy, and being more willing to adjust their eating habits;

Behavior: changing eating frequency of different types of food, adjusting dietary structure, and utilizing nutrition reference information such as food labels.

The game set, as

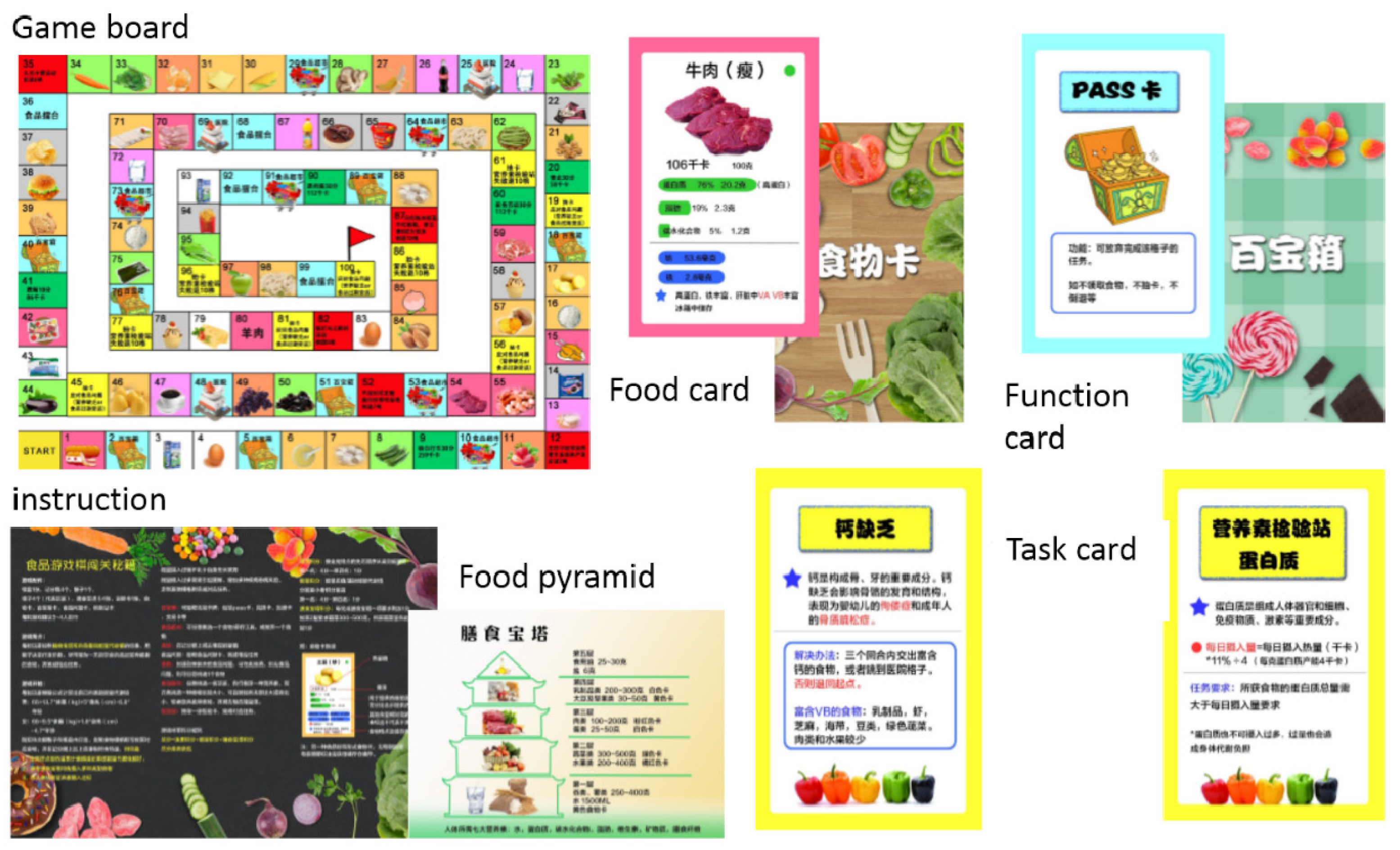

Figure 1 shows, is comprised of following parts:

The game map;

Food pyramid card: it has five floors, listing daily recommended intake of different type of food. It is the reference of food selection and grades accounting;

Food card: 50 kinds of common food, including meat, egg, diary, vegetables, fruits, grains, and puffed food;

Treasure box card: eight kinds of function, including skip, pass, acceleration, cooking, exchange, stealing, transfer, and adding food;

Food problem card: eight kinds of tasks, including calcium deficiency, iodine deficiency, iron deficiency, vitamin A deficiency, vitamin B deficiency, vitamin C deficiency, food deterioration, and food poisoning. Students need to draw out one card and complete tasks on it;

Testing station: six kinds of nutrients, including protein, fat, carbohydrate, fiber, sodium, and high GI (glycemic index) food. Students need to check whether their total amount of a nutrient fit the standard.

Figure 1.

The sketch of the board game set.

Figure 1.

The sketch of the board game set.

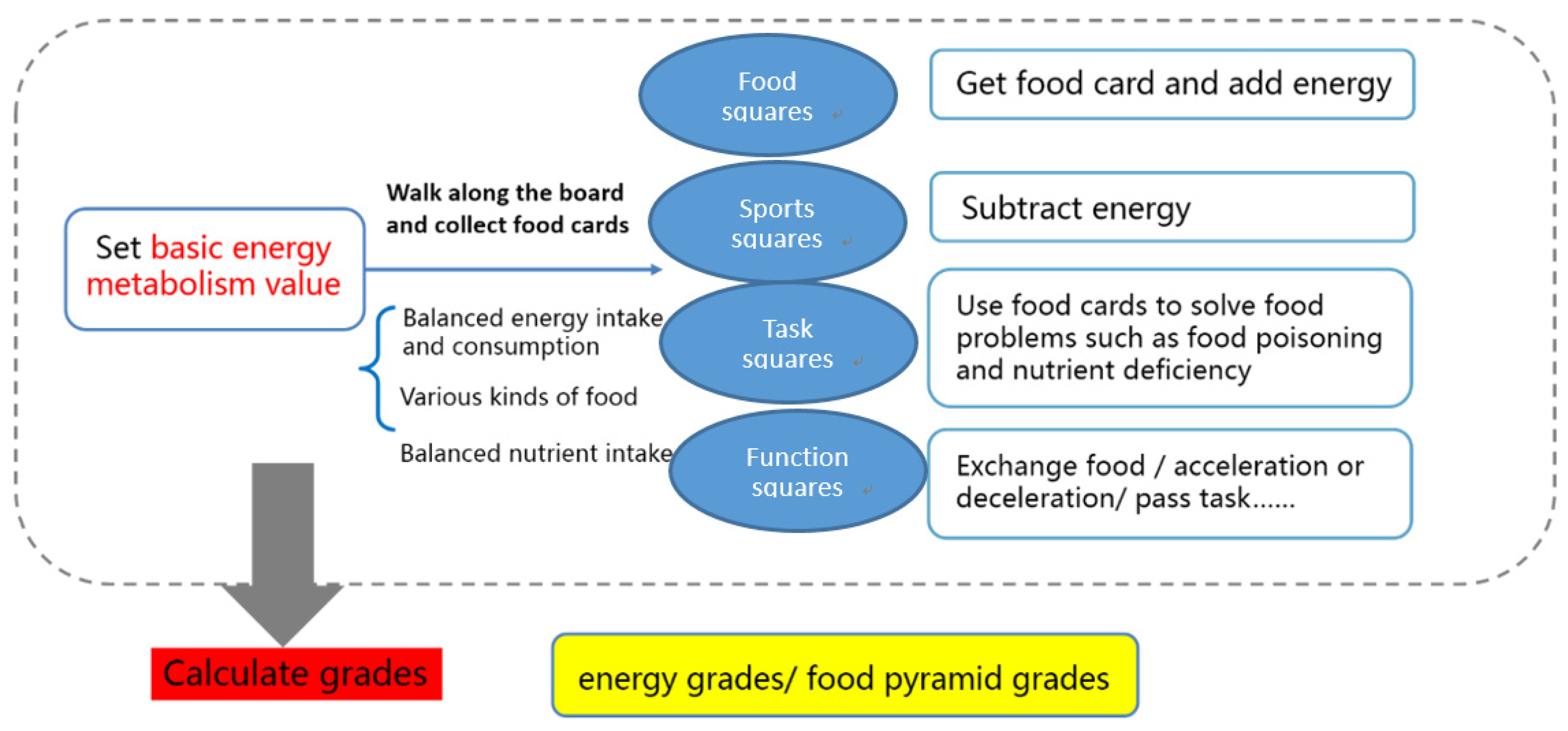

2.3.2. Game Rules

It is suggested that 3–5 students play the game together. Boys set the basic energy metabolism rate as 1400 kilocalories per day and girls set it as 1200 kilocalories per day. They then throw the dice to move their pieces on the board and complete corresponding tasks. The detailed procedures can be seen from

Figure 2, as explained in the following:

2.3.3. Game Designing Principles

First, based on the key points in the literature review, this game involves two elements: quantitative thinking and more operational knowledge. During the process of energy calculation and dietary pyramid calculation, students need to remember the energy and nutrient value of different foods, which helps them to deepen memories; when stepping into task checks, they need to solve problems on the food cards they have collected, which amounts to the utilization of the knowledge, helping them to establish linkages between theories and reality.

Second, according to the food pyramid, it is suggested to eat a higher proportion of vegetables and less meat, but there are more meat and high-fat food checks and fewer vegetable and fruit checks on the board. Therefore, students need to use strategies to acquire more healthy food cards and abandon unhelpful cards.

Third, some food task checks set punishment for going backwards, helping students to strengthen awareness of avoiding some unhealthy dietary habits, such as unreasonable dietary structure and unbalanced intake of nutrients.

Last, the final grades contain multiple dimensions, which requires students to think more and use more strategies and knowledge. “Speed grades” are designed for entertainment. “Energy grades” are intended to test whether students can consider the energy intake in an overall view. “Food pyramid grades” are designed to test whether students mastered the balanced intake of different types of food.

The professional part of the game refers to teaching materials of food nutrition [

19], and the content has been checked by associate professor Chen Yanhui of food science and nutrition engineering college at China Agricultural University, so the game can be guaranteed to be scientific.

2.3.4. Questionnaires

The questionnaires used in pre- and post-test have four parts: basic information, nutrition quiz, dietary attitude scales, and behavior scales.

Basic information includes name, gender, height, and weight (for the calculation of BMI).

Food nutrition knowledge comprises three parts: food and nutrient (nine questions), food pyramid and dietary structure (three questions), and food safety and package (three questions), 15 questions in total. All questions refer to the literature of An [

20], Zhao [

21], and national nutritionist exam questions. The proportion of different parts of knowledge points corresponds to their distribution in the game.

Dietary attitude questions are in the form of Likert scales, nine items in total, which comprise three dimensions: the awareness of the importance of healthy diet, self-efficacy of the command of nutrition knowledge, and the willingness to adjust dietary behaviors. All items are adapted from the research of Turconi [

22]. The Cronbach’s alpha value ranges from 0.773 to 0.8.

Dietary behavior questions contain food intake frequency scales (11 items) and Likert scales (seven items). All items are adapted from the research of Anderson [

23]. The Cronbach’s alpha value ranges from 0.794 to 0.818.

2.4. Implementation Schemes

As can be seen from

Figure 3, students were divided into six groups (3–4 students in one group) to play the game. Each activity lasted about 30 min. In the first five activities, a tutor led students to discuss playing skills based on certain topics in the first 10 min, as can be seen from

Table 2. And the difficulty of the game would be increased step by step, during which the knowledge points were delivered to students in a more interesting way.

2.5. Data Analysis

SPSS 19.0 was used for data analysis. Due to the small sample size, Wilcoxon rank test was used in the analysis of the teaching effect of the board game. The Mann–Whitney rank sum test was used to analyze the differences of learning effects among students with different gender and physical indicators.

3. Results

3.1. Students’ Change in Knowledge, Dietary Attitude, and Behavior

Food nutrition knowledge test contains three parts: food and nutrient, food pyramid and dietary structure, and food safety and package, with grades of 14 points, 4 points and 5 points, 23 points in total. As can be seen from

Table 3, students’ total knowledge grades increased significantly after the 6-week intervention. In specific knowledge points, students had significant increases in two dimensions: food and nutrients and food safety and package. Most students had better command of nutrient deficiency, what food contained high level of nutrients, and food pyramid structure. In contrast, for some questions that needed comparison (e.g., which of the following foods has the highest calorific value?) and questions about GI that had lower prevalence in the game, students showed less improvement.

Dietary attitude scales contained three dimensions: the awareness of the importance of a healthy diet, self-efficacy of the command of nutrition knowledge, and the willingness to adjust dietary behaviors. As can be seen from

Table 4, students significantly increased scores in importance awareness and self-efficacy, but there were no significant changes in willingness to adjust.

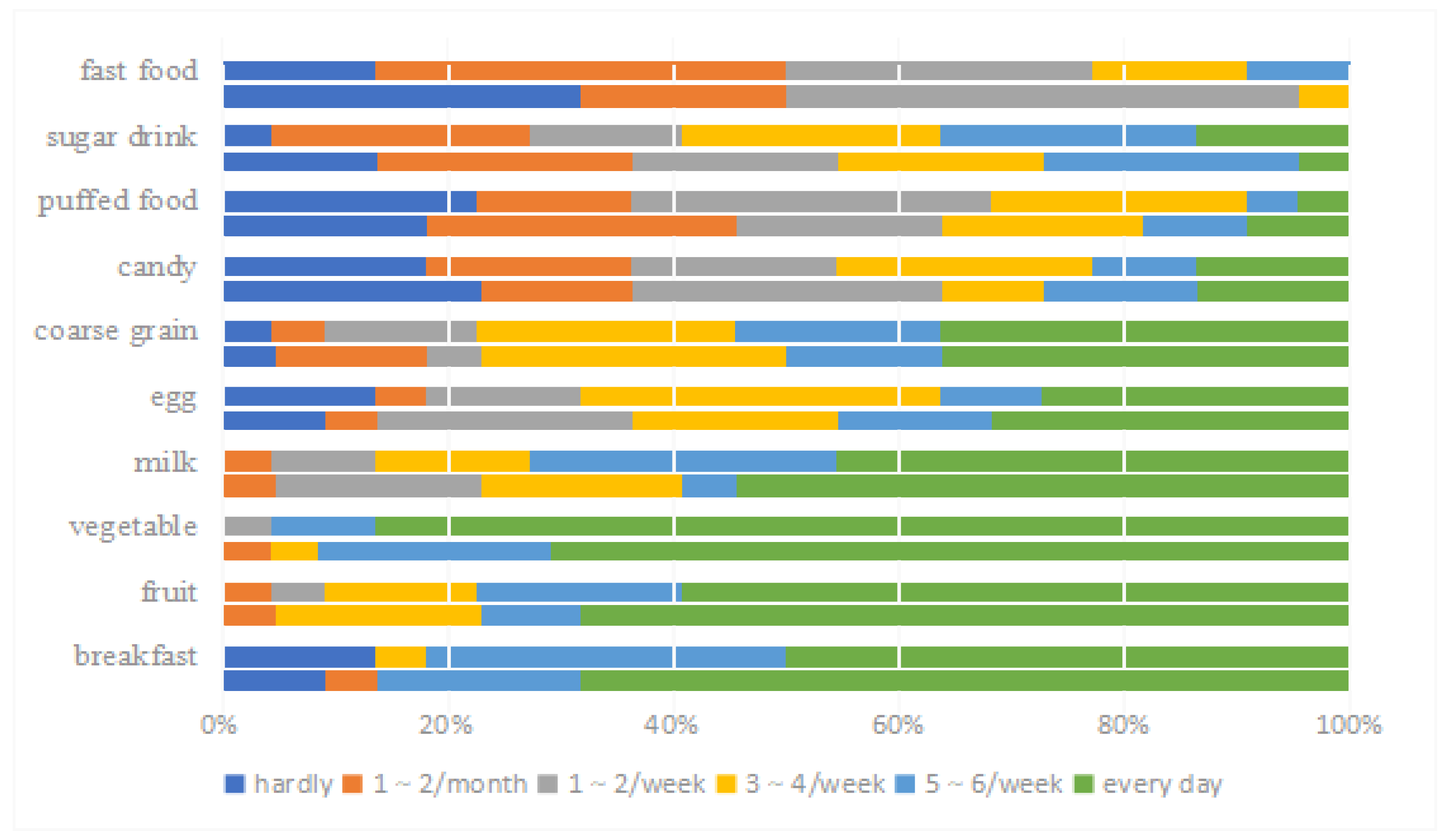

Figure 4 shows students’ intake frequency of different types of food before and after the game activities. Breakfast, fruits, vegetables, milk, eggs, and coarse grains are recommended for higher intake frequency (every day); candy, puffed food, sugary drinks, and fast food, which have little nutritional value, are recommended for lower intake. As can be seen from the

Figure 4, students already had a relatively reasonable dietary structure. Approximately 80% of students had breakfast, fruits, and vegetables more than 5 days per week. Among recommended food, eggs and coarse grains were two kinds of food with relatively low intake frequency. More than 60% of students ate candy, puffed food, and fast food less than 2 days per week. Among not recommended food, sugary drinks had higher intake frequency.

After the 6-week intervention, the number of students who ate breakfast and fruit with higher frequency had increased. For vegetables, the number of students who ate it every day had decreased, but the overall change was not large. For milk, there was a small increase in the number of students who drank it every day or with low intake frequency. The number of students who ate eggs with higher frequency increased. There was little change in the intake of coarse grains. Among food not recommended, the average intake frequency of sugary drinks and fast food had decreased. The intake frequency of puffed food and candy had only a slight fluctuation.

Dietary behavior scales contain three dimensions: balanced intake of nutrients (students make some food paring adjustments between meals to achieve balanced intake of nutrients), food intake frequency (students increase the intake of recommended food such as fruits and vegetables and reduce the intake of not recommended food), and reading food labels (students pay more attention to food labels when buying goods).

As can be seen from

Table 5, students significantly increased their scores in food intake frequency and reading food labels, which corresponded to the result of

Figure 4 to some extent.

3.2. Students’ Change in Delay Test

The delay test was designed to investigate whether students’ attitude and behavior would be further improved over time. In terms of attitude, there were not significant changes in the scores of the delay test compared with the post-test. However, students’ scores of willingness to adjust (4.61 ± 0.64) were significantly higher than those in the pre-test (Z = 2.32, p < 0.05). In terms of behavior, there were not significant changes in scores of balanced intake of nutrients and food intake frequency between the delay test and the post-test. Scores of reading food labels (4.09 ± 0.75) had significant decrease compared with those in the post-test (Z = 2.71, p < 0.01).

3.3. Difference in the Effects of Board Game on Students with Different Gender and BMI

Due to the small sample sizes after the split of all students, there may be some error in the analysis. As can be seen from

Table 6, there was no significant difference in knowledge scores between boys and girls. In terms of willingness to adjust, only girls had significant increasing scores, with little change on the level of all students. In terms of other dimension of attitude and behaviors, boys and girls had different changes. In the dimension of importance awareness and food intake frequency, only girls had significant improvement. In the dimension of self-efficacy, only boys had significant improvement.

According to BMI standards, normal BMI ranges from 18.5 to 24. A BMI of more than 24 means overweight, and a BMI of less than 18.5 means underweight. Students were divided into two groups: normal BMI group (9 students) and abnormal BMI group (13 students). As can be seen from

Table 7, the abnormal BMI group had significant increasing scores in multiple dimensions, including self-efficacy, food intake frequency, and reading food labels, whereas there was little change in the normal BMI group.

In the pre-test, scores of self-efficacy in the abnormal BMI group were significantly lower than that in the normal BMI group (z = 2.31, p < 0.05), and scores of willingness to adjust were significantly higher (z = 1.98, p < 0.05).