1. Introduction

The assessment of learning outcomes is an essential element of curriculum design, but even well-designed assessments are a major source of stress and anxiety in University students [

1]. While the methods and scheduling of assessments have a significant influence on the measured performance of examinees [

2], advanced assessment strategies such as integrated block testing go beyond a mere improvement in measurement, and instead improve the actual learning outcomes of the curriculum [

3,

4]. Particularly in the demanding medical school curricula, with frequent high-stakes examinations, assessment formats and schedules are a major source of student stress [

5], and need to be carefully designed to provide an authentic measure of learning, as well as to favor the understanding of key concepts over the short-term memorization of facts [

6].

While it seems obvious that the scheduling of exams can have a major impact on measured performance and student satisfaction, only a few studies have attempted to quantify scheduling effects on academic performance in isolation of any other curricular changes [

7,

8]. In particular, the influence of time between exams on academic performance has been understudied, and the only available comprehensive data on such scheduling effects are limited to an analysis of the performance of high school students [

2]. In the medical school setting, changes in exam schedule are usually part of a global change in assessment strategy [

9]. Systems-integrated scheduling (SIS) is a well-established curricular approach to foster the integration of subject material through coordinated teaching and assessment across disciplines in a coordinated block format [

10]. While the change from discipline-specific to integrated exams was described as broadly positive [

11], a detailed quantitative analysis showed that exam integration in SIS curricula has a more complex and not entirely positive impact on student academic performance [

12], with students scoring lower overall on integrated exams than on the more traditional separate discipline-specific exams, but showing improved performance on the more complex questions of higher Blooms taxonomic classification. As was concluded at the time of implementation, SIS requires deliberate careful planning to leverage the benefits of content integration for more meaningful learning [

10].

The present study was primarily undertaken to assess the effects of the back-to-back (B2B) scheduling of two basic science course exams on student academic performance in the preclinical curriculum at a large US osteopathic medical school. No intentional effort was given within this study to integrate course content or assessment items. A second, related aim of the present study was to capture student opinions on the B2B testing schedule through a systematic analysis of comments on the annual student satisfaction survey. In its narrow scope to assess scheduling effects in isolation of any other curricular changes, the present study differs significantly from related work on the effects of SIS on learning outcomes. While this difference limits the applicability of the extensive theoretical framework on curricular integration [

13], it highlights the unique value of the study as a unique opportunity to disentangle the effects of exam scheduling from other effects of curricular integration.

In 2019, examinations in Biochemistry/Genetics and Medical Cell & Tissue Biology courses were administered on the same day with a 15 min break, instead of being spaced 7–14 days apart as had been done in prior years. It was reasoned that even in the absence of other curricular changes, the simultaneous testing of related subjects would contribute to a deeper understanding of complex materials by encouraging integrated study, and would help to improve student satisfaction by reducing the number of exam days. Based on this rationale, it was hypothesized that the B2B schedule would lead to an increase in measured learning outcomes, accompanied with an increase in the subjective measure of satisfaction with the curriculum—two measures that are long known to be correlated [

14,

15]. In addition, it was hypothesized that the increased length of the combined assessments would be recognized as beneficial, as it would allow students to build stamina for medical licensing examinations and could give insights into potential effects of exam length on performance in the medical school setting [

16,

17].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design and Intervention

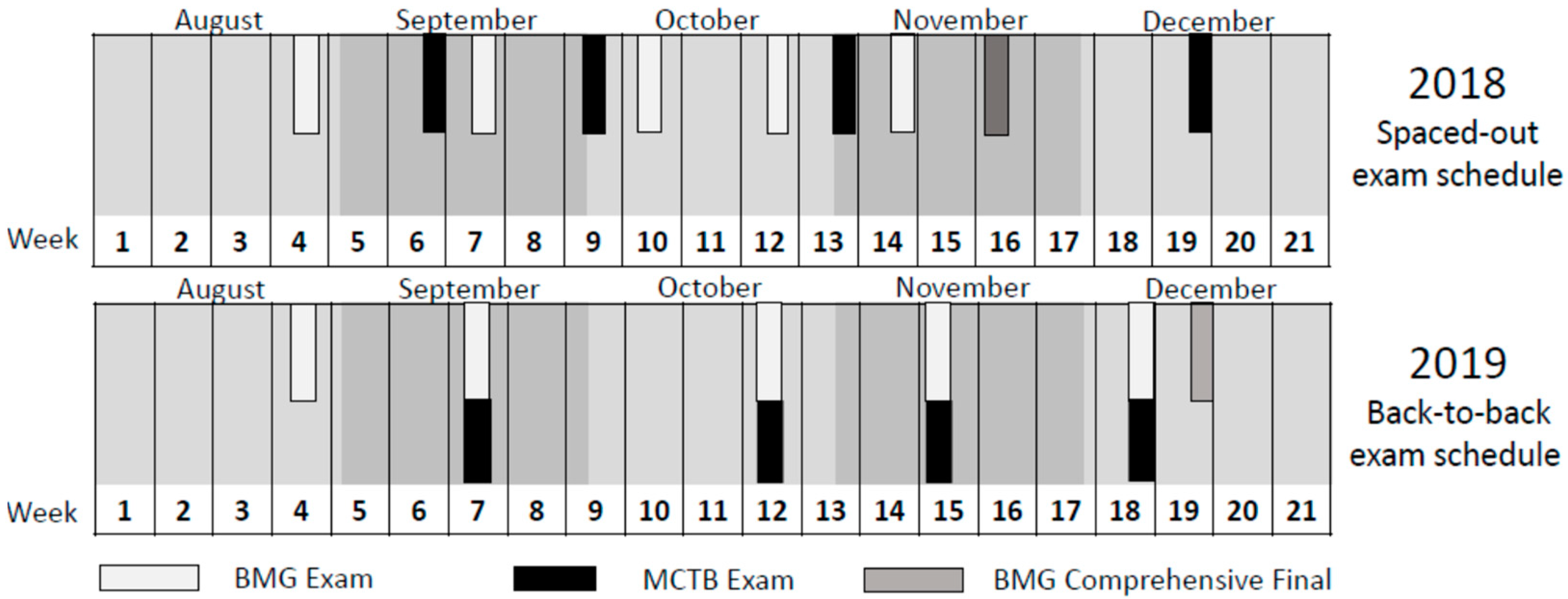

In the fall semester of 2019, the Des Moines University College of Osteopathic Medicine (DMU-COM), a large US Osteopathic Medical School, changed the scheduling of exams in two parallel courses, Biochemistry/Molecular Genetics (BMG, 4 credits) and Medical Cell & Tissue Biology (MCTB, 4 credits). Following an administrative decision with limited faculty and student input, the exam schedule was changed from a spaced-out system (SO) to a back-to-back model (B2B; see

Figure 1). No other curricular changes were made, and no significant changes were made to the exams. In both models, students were given 75–83 min to complete 50–55-question multiple choice examinations. In the 2018 SO model, the exams were 7–14 days apart, while in the 2019 B2B model the MCTB exam was scheduled following the BMG exam after a 15 min break (necessary for technical reasons). Students who submitted the first exam before the end of the allotted time were thus given a longer break between exams.

2.2. Assessment Strategies and Exam Administration

DMU-COM uses a competency-based assessment strategy featuring both formative and summative examinations. Course content and exam questions are linked to the Osteopathic Core Competencies [

18], with competencies II. Medical Knowledge and III. Patient Care being most frequently taught and assessed. For each MCTB and BMG exam, students were given a full-length formative practice quiz, which is not included in the grade. As an additional formative element in both exams and practice quizzes, students are shown the question rationales and linked course objectives after the exam has concluded. Exams were administered on-campus with live proctoring using the Examsoft testing platform (Examsoft, Farmers Branch, TX, USA). Students were given a presentation during orientation to explain the nature of and the rationale behind the scheduling change. Study authors (MS and SW) served as directors for the BMG and MCTB courses, respectively. In addition to these courses, students were also required to take courses in Anatomy (5 credits), and other program-specific offerings such as Clinical Medicine (1.5 credits) and Osteopathic Manual Medicine (2.5 credits). The exams in all other courses followed the SO schedule, and did not coincide with the combined BMG/MCTB tests.

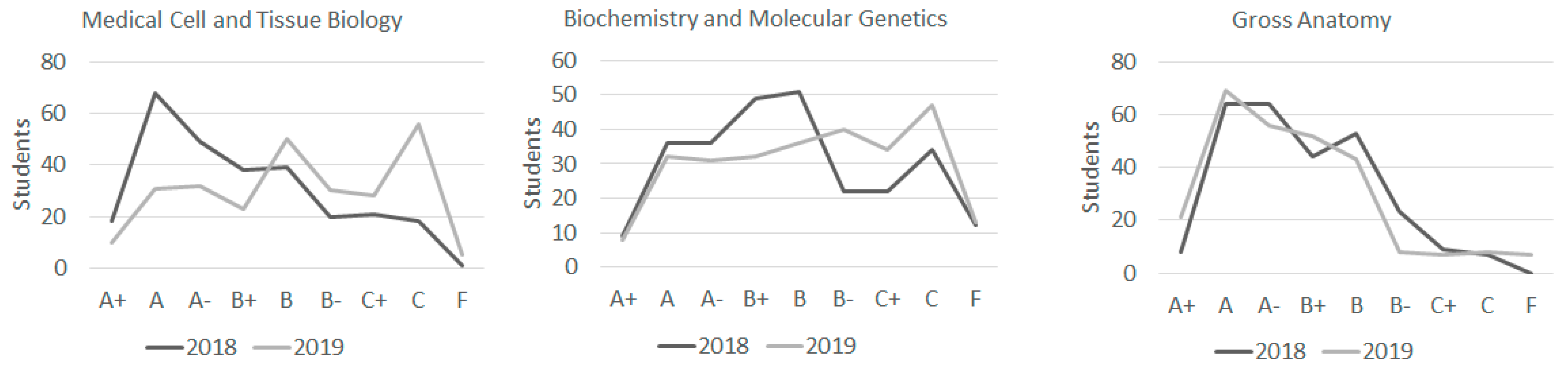

This curricular change set up a natural experiment, which allowed a post-hoc cohort study comparing measures of academic performance and student satisfaction between the 2018 cohorts of 271 first-year osteopathic (DO22) and podiatric medicine (DPM22) students (assessed with SO schedule) and the 270 members of the respective 2019 cohorts (DO23 and DPM23, assessed with B2B schedule).

2.3. Characterization of Study Cohorts

De-identified academic and biographical data of the DO22, DO23, DPM 22 and DPM23 study cohorts were obtained from the University Admissions Department and compared for significance using two-tailed students’ t-test for all values except for male/female ratio, which was analyzed for significance with a Chi Square test (Microsoft Excel, Redmond, WA, USA).

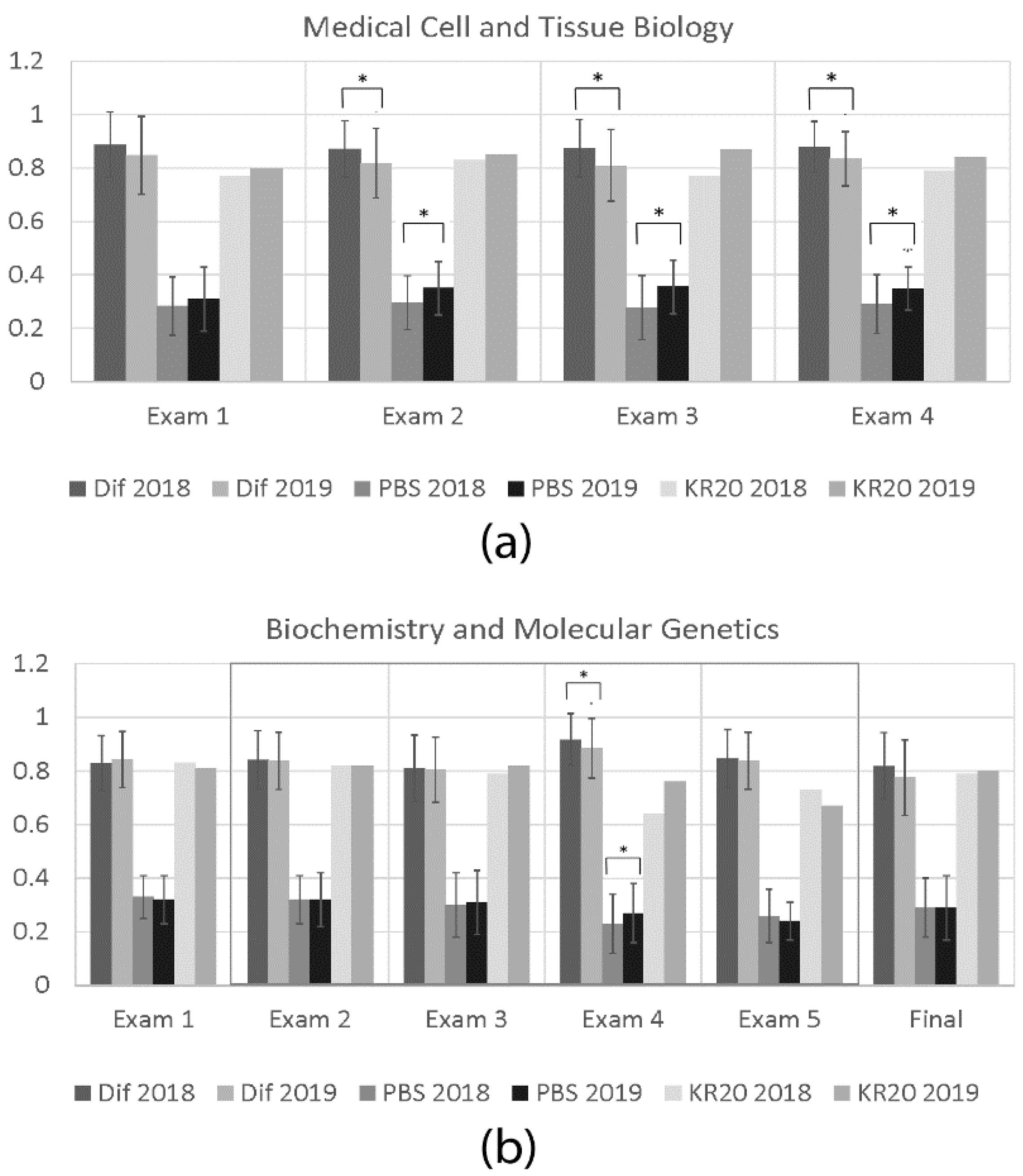

2.4. Measurements of Academic Performance

The influence of the exam schedule on students’ academic performance was determined by analysis of exam item performance (difficulty and point biserial), exam reliability (KR20 values) and course grades using the tools available through the exam administration software. Items that were changed or replaced during the 2018/2019 transition were excluded before further analysis. Exam reliability, average point biserial and the difficulty of 10 BMG/MCTB exams, as well as course grades, were analyzed for significance in differences using non-parametric testing (Mann–Whitney U testing; SPPS, Chicago, IL, USA).

2.5. Measures of Student Satisfaction

Student satisfaction with the curricular scheduling was determined by qualitative analysis of responses to the routine annual spring survey of students of osteopathic medicine. This comprehensive survey is conducted annually by the COM Dean’s office and collects information to support improvements in educational programming and student learning. Survey participation is optional, and the survey contains no forced items. The OMS1/OMS2 survey contains 100 response items, including 3 free-text response items. Survey participation among 2018 and 2019 first- and second-year students was between 61% and 67%. Free-text responses relating to the exam schedule were coded by two investigators (BP, MS) for positive, neutral or negative impressions on the B2B testing schedule, for emerging common themes describing the problem with the B2B schedule, as well as for statements indicating a connection between exam schedule and stress. Inter-rater reliability testing was performed using Cohen’s kappa [

19] (Microsoft Excel, Redmond, WA, USA). Text narratives from survey respondents were selected for presentation.

4. Discussion

The question of the optimal scheduling of exams and other cognitive tasks is of great importance for educators, as simple changes in exam schedule can influence the measured performance of examinees [

2,

8]. Learner performance evaluation is of particular importance in medical education, where a demanding curriculum with frequent high-stakes examinations creates a competitive environment that has long been understood to contribute to the high prevalence of anxiety, stress, depression and burnout among medical students [

21,

22]. Given that long, frequent and challenging examinations are a major driver of medical student stress [

1], curricular reforms at medical schools encompass novel assessment strategies that aim to reduce testing stress and are designed to favor a deep understanding of biomedical concepts over the short-term memorization of facts [

9].

A time-tested approach to improve the learning experience in medical education is the bundling of related assessments in a systems-integrated block schedule model [

3,

10]. In systems-integrated scheduling (SIS), curricular content is coordinated in a systems-based format to allow the integration of topics across related courses and the assessment of learning in fewer, integrated examinations. It was argued that the SIS of exams in a block frees time for uninterrupted study, and that the simultaneous assessment of related subjects would foster knowledge integration, as it requires students to stay current in multiple related courses—particularly when the assessment features integrated questions covering several knowledge domains [

3]. However, since the examination schedule is usually only one element of a broader curriculum reform [

9], it is difficult to separate the effects of scheduling from the effects of other measures to foster content integration. In addition, ethical concerns and logistical problems often preclude the execution of true randomized–control trials for the assessment of curricular interventions, limiting the availability of reliable data [

23]. The present quasi-experimental study is unique and different from related studies on exam scheduling, in that it examines the effects of exam stacking in the absence of other curricular reforms, and thus provides novel insights into the scheduling effects of medical school exams. It was hypothesized that in spite of its fundamental differences, the B2B testing of related subjects would provide benefits similar to the established SIS model, by primarily improving measured learning outcomes and secondarily improving student satisfaction with curricular scheduling.

In this study, we demonstrate that student cohorts experiencing B2B scheduling of exams in Biochemistry/Molecular Genetics (BMG) and Medical Cell & Tissue Biology (MCTB)—two related courses in the first year of the medical programs at Des Moines University—show lower academic performance and lower levels of satisfaction with curricular scheduling than the cohorts tested with the traditional SO model. While these observations could be caused by any number of confounding factors that were not controlled in this natural experiment, it is tempting to speculate that the testing schedule is the major factor behind the negative outcomes of the intervention. A further complication would include both direct and indirect impacts related to the examination schedule. While it is possible that there were some benefits of these changes, these appeared to be outweighed by the negative factors in this study. This result is somewhat unexpected, as a recent related study on exam timing has shown that scheduling effects on exam performance are complex, with warm-up effects balancing fatigue and distraction counteracting the benefits of recuperation [

2]. In this 2020 study, the authors demonstrate that a shortened time between exams can improve measured academic performance, particularly for high-achieving students testing in STEM subjects, but it also was evident that cognitive fatigue negatively affects performance in closely spaced analytic reasoning-intensive tasks [

2,

8].

The thematic coding of osteopathic medicine students’ comments on the annual survey suggests an explanation for the observed negative effects of exam stacking in the study cohort. A full 40% of survey respondents specified that simply stacking exams in related courses is not conducive to learning, and that the benefits of block scheduling can only be realized if courses are fully integrated (sum of comments on “poorly coordinated subjects” and “not properly implemented block schedule”). As Harden pointed out in his groundbreaking work on the integration ladder [

24], curricular integration occurs on several levels. In Harden’s categorization, the DMU-COM BMG and MCTB courses only reached the basic integration levels of mutual awareness and harmonization of content; no attempts towards further content integration were made to accompany the introduction of B2B scheduling. Student comments suggested that for the block scheduling of exams to have a beneficial effect, curricular content should be fully coordinated and presented in a multidisciplinary approach; student and faculty input should be sought and incorporated to ensure the success of integration efforts. This may help explain some of the differences seen in this study as compared to more unified integration efforts presented in other studies [

11]. While we did not set out to explicitly determine measures of student stress, our analysis of survey data regardless suggests that one of the reasons that the B2B schedule is perceived as detrimental to learning is that it produces stress and exhaustion, as students are simultaneously preparing for exams in two challenging courses. In this way, the B2B examination approach may have limited the utility of a student examination preparation strategy that included cramming, without offering the benefits suggested by more integrated approaches.

It is worth noting that the 2019 scheduling change was accompanied by a stronger decrease in academic performance in the MCTB assessments than in the paired BMG exams. For this observation, there are two, not mutually exclusive explanations: exam timing and course policy. First, since the MCTB exams were administered after the BMG assessments, they were more strongly affected by the cognitive fatigue of examinees. The randomization of exam order could have helped to eliminate this confounding variable; however, since the study was performed as a natural experiment, the experimental conditions were not under the control of the investigator. Second, the courses had different policies regarding the remediation of poor exam performance. In contrast to the policies in the BMG course, the MCTB course offered students immediate opportunities for grade improvement through the retesting of a failed exam. Informal communications with students showed that this policy was seen as more forgiving than the BMG course policy of grade replacement, where only one poor score could be substituted with the score of the final comprehensive examination. We conclude that, when faced with an overwhelming amount of material to prepare for two courses, students prioritize efforts in the course with higher stakes related to poor exam performance and lower chances of grade adjustments. This may have allowed students to utilize more familiar examination preparation strategies that provided additional time between the exams by postponing the true assessment of MCTB knowledge to the retest.