Abstract

This systematic review examined the effects of distinct physical activity interventions on the academic achievement of school students based on an analysis of four distinct outcomes: mathematics, language, reading, and composite scores. This study was performed in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines and the QUORUM statement. A literature search was conducted using the PubMed-MEDLINE, Scopus, and Web of Science databases. Peer-reviewed studies published in English, Portuguese, and Spanish were considered. A random-effect meta-analysis was employed to determine the effect of interventions on academic performance. The effects between interventions and control groups were expressed as standardized mean differences. Thirty-one studies were included in the meta-analysis based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The exercise programs were not capable of significantly improving language, reading skills, and composite scores. Conversely, performance in math tests increased significantly after the interventions compared with the control groups. Regarding the overall effect, a significant improvement in academic achievement was detected after physical activity programs compared with controls. In conclusion, the positive effects of school-based physical education on academic performance are not uniform and may be higher for math skills. The implementation of evidence-based exercise programs in school settings emerges as a promising strategy to increase overall academic achievement in school-aged students.

1. Introduction

Over the last few decades, the rate of sedentarism has increased dramatically around the world, currently being considered a “public health issue” [1,2,3,4]. Overall, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), approximately one-third of individuals aged 15 years or older are physically inactive, which potentially results in more than 3 million premature or preventable deaths annually [1,5,6]. In fact, about 5.5% of all deaths worldwide have been attributed to sedentarism, a number that places this growing health concern among the five major risk factors for mortality in adult life [5,7]. Among other things, physical inactivity significantly increases the risk of several chronic diseases, such as different forms of cancer, diabetes, hypertension, dementia, coronary and cerebrovascular events, bone disorders, and obesity [8,9]. Together, these findings highlight the severity of this “global epidemic” and reinforce the need for urgent and effective strategies to increase the levels of physical activity and to reduce sedentary behavior among the general population [3,10,11].

The adverse effects of sedentarism have been consistently recognized to affect distinct age groups, but more recently, a growing body of research has been conducted to evaluate its specific effects on youths [11,12,13]. Indeed, a progressive decline in physical activity participation is commonly observed during the transition from childhood to adolescence, suggesting that many adolescents are at risk of becoming sedentary adults [14,15,16]. It has been shown, for example, that a gradual decrease in physical fitness from childhood to adult life is associated with obesity and insulin resistance in adulthood [17]. From an applied standpoint, this means that the vast majority of children with obesity tend to become obese and “potentially unhealthy” adults [17,18]. In contrast, long-term programs and strategies aimed at maintaining high levels of physical activity during different life stages, from childhood to adulthood, may likely reduce the probability of developing obesity and other chronic diseases (e.g., type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, hypertension, osteoporosis, etc.) throughout adulthood [18,19,20]. As such, there is no doubt that regular exercise, especially when performed uninterruptedly from earlier life stages, has numerous physical and physiological benefits [21,22,23,24].

Lower levels of physical activity in childhood and adolescence are also associated with body image dissatisfaction, obesity, and adult depression [25,26,27]. On the other hand, the involvement in sport activities seems to influence the development of important coping and stress management skills in youths, which emphasizes the role played by physical activity in promoting mental health and in preventing mental illness [24,28,29,30]. Furthermore, there is evidence suggesting that physical activity can also improve cognitive function and learning abilities in both children and adolescents, thus impacting their academic achievement in different areas of knowledge (e.g., mathematics and languages). A recent review addressed this issue in a very comprehensive manner, finding meaningful relationships among physical activity, fitness levels, and academic performance in elementary-aged children (i.e., aged 5–13 years) [31]. Two other reviews have specifically examined the effectiveness of school-based physical activity in academic life, providing encouraging and relevant results [32,33]. Briefly put, the regular practice of physical education in school settings was shown to be capable of improving learning skills through different cognitive processes (e.g., increasing attention and concentration) and was equally efficient in inducing positive changes on a variety of important outcomes, such as quality of life, and social and affective behaviors [32,33].

Although the benefits of physical education are well-established, to date, no review has systematically assessed its effects on different subjects and fields of study in a separate manner (i.e., analyzing its effects on mathematics, language, and reading skills) or in combination (i.e., using “composite scores”). This is essential to provide a deeper and more detailed understanding of the actual effects of physical education on the academic performance of school students. Therefore, the objective of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to evaluate the effects of distinct physical activity interventions on the academic achievement of school students, based on the individual analysis of four distinct outcomes: mathematics, language, reading, and composite scores. We hypothesized that the regular practice of physical education in schools would positively and equally affect academic performance, regardless of the subject being examined.

2. Methods

2.1. Literature Search and Data Resources

This research was completed in accordance with the Preferred Reported Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA) guidelines [34] and the QUORUM statement [35]. The literature search included studies published until 13 December 2021 and was conducted using the following databases: PubMed MEDLINE, Scopus, and Web of Science. Keywords were defined based on previous works [36,37] and according to the study purpose by two authors (I.L. and L.A.P.). The following keywords were used in conjunction with the Boolean operators “AND” and “OR” as part of the search strategy: “students”, “schoolchildren”, “physical activity”, “physical education”, “sport”, “exercise”, “academic performance”, “academic achievement”, and “school grades”. The reference lists from relevant articles were also examined to find any other potentially eligible studies.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Peer-reviewed studies published in English, Spanish, or Portuguese were considered for inclusion, and no sex or time of intervention restrictions were imposed. Studies were included based on the following criteria: (1) original studies; (2) quantitative assessment of “academic performance” pre- and post-intervention; (3) at least one group allocated to a physical activity intervention; and (4) samples composed of kindergarten, elementary, middle, or high-school students. Additionally, in relation to the exclusion criteria, studies were not considered for analysis if (1) they were written in other languages; (2) no comparison group was tested; (3) only acute effects were assessed; (4) they were qualitative studies; or (5) no full text or data regarding the main outcomes were available.

2.3. Study Selection

The initial search was carried out by two researchers (I.L. and L.A.P.). After the removal of duplicates, titles and abstracts were screened and studies not meeting the eligibility criteria were excluded. Subsequently, full texts of the remaining articles were analyzed. Next, in a blind, independent fashion, two reviewers selected the studies for inclusion (I.L. and L.A.P.), following the eligibility criteria. If no agreement was obtained, a third independent and experienced researcher, not involved in the study, was consulted.

2.4. Data Extraction

Mean, standard deviation (SD), and sample size data were extracted from the included manuscripts by two authors (I.L. and L.A.P.). If the descriptive data required were not presented in the articles, authors were contacted via email, and in case of no answer or if the requested data were not available, the study was not considered in the analysis. Any disagreements during the process of data extraction and analysis were resolved by consensus among two authors (I.L. and L.A.P.).

2.5. Data Analysis

The meta-analysis was performed using Review Manager software (RevMan 5.4.1; Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK). A random-effect meta-analysis was conducted to determine the summary effect of the interventions on academic performance. Effects between intervention and control groups are expressed as standardized mean differences (SMD) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI). Standardized mean differences were used because academic performance was obtained through distinct methods. Academic performance data were divided into subgroups, according to distinct assessed subjects (e.g., language, mathematics, reading, and composite scores).

Heterogeneity among studies was assessed using I2 statistics. I values ranged between 0% and 100% and were considered low, modest, or high for <25%, >25–<50%, and >50%, respectively. Heterogeneity may be assumed when the p value of the I test was <0.05 [38]. Statistical significance was considered for p < 0.05.

2.6. Risk of Bias and Quality of the Studies

Methodological quality and risk of bias were assessed through the Cochrane risk of bias tool (RoB 2.0) [39] by two authors independently (I.L. and L.A.P.), with disagreements being resolved by a third independent evaluator (not involved in the study), in accordance with the Cochrane Collaboration Guidelines [40].

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

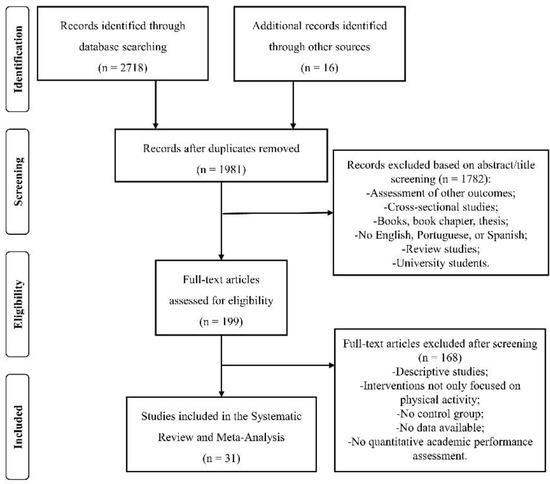

Figure 1 depicts a flow diagram of the process of study selection. A total of 2718 records were identified through database searching, and 16 additional studies were identified through other sources. After title and abstract screening, from the 1981 studies that remained after removal of duplicates, 1782 studies were excluded. As a result, 199 studies were assessed for eligibility and 31 studies were included in the meta-analysis based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. From the articles included, 4 assessed academic performance through language tests [41,42,43,44], 24 used mathematics tests [41,42,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65], 10 reading assessments [44,46,47,49,50,57,59,60,63,64], and 9 evaluated academic achievement using composite scores (e.g., student’s grades or standard tests) [41,44,59,66,67,68,69,70,71].

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the process of study selection.

3.2. Characteristics of the Interventions

The characteristics of the training programs and the overall risk of bias of the included studies are displayed in Table 1. The interventions implemented in the distinct studies comprised increasing the volume of physical education classes [41,68], applying classroom-based activities in the regular school practices [66], promoting “active” breaks between regular classes [54,69], and employing specific programs of “active” lessons [49,51].

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis.

3.3. Main Effects and Sub-Group Analyses

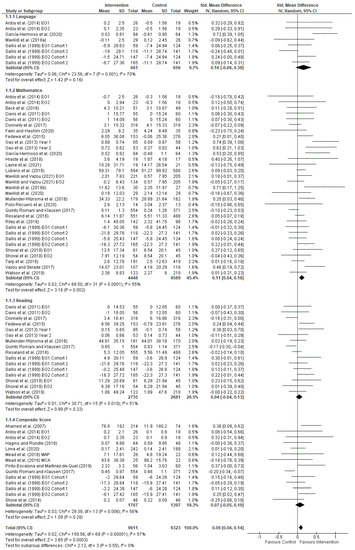

Figure 2 depicts the forest plot for the effects of the physical activity interventions on the academic performance of students from several grades. The sub-group analyses revealed that the interventions were not capable of significantly improving academic achievement in language, reading, and composite scores. In contrast, performance in the mathematics tests significantly improved after the interventions when compared with control groups. In relation to the overall effect, a significant improvement in academic performance was noticed after physical activity interventions when compared with their respective controls. Overall, irrespective of the sub-group analyzed, the studies presented high levels of heterogeneity (I2 > 50%).

Figure 2.

Standardized mean difference (95% confidence intervals, CI) between intervention and control groups. Squares represent the SMD for each trial. Diamonds represent the pooled SMD across trials.

4. Discussion

In this systematic review, we examined the effects of different types of physical activity programs on the academic performance of school students. After analyzing these effects on an individual basis (i.e., via sub-group analyses), it was possible to verify that these interventions did not increase academic achievement in language skills, reading skills, and composite scores. In contrast, performance in mathematics significantly improved, which reveals the important role played by physical education in some specific learning processes and cognitive functions. Moreover, an analysis of the “overall effect” (i.e., through the use of a pooled computation, considering all scores simultaneously) confirmed that physical activity interventions are useful resources for enhancing the academic performance of children and adolescents.

The contrasting results among the different subjects and learning abilities (i.e., mathematics, language, and reading skills, and composite scores) are difficult to interpret and may also be influenced by a variety of external factors (i.e., type and mode of exercise, duration and frequency of training intervention, etc.) [59]. However, some similar results can be found in several studies, thus requiring more detailed discussion. In this regard, Quinto Romani et al. [59] examined the effects of five distinct training programs on the academic performance of 1479 Danish students and reported some interesting findings: (1) on average, all interventions seem to have a “very limited beneficial impact” on academic achievement; (2) this beneficial impact tends to be higher for “high-intensity training programs”. The superior effects of more intensive training sessions on cognition and learning skills were also highlighted in other investigations on this topic [41,44,50,62]. For example, Ardoy et al. [41] analyzed the role played by exercise frequency and intensity on academic success by comparing the effects of three different experimental conditions: (1) standard physical education (“control group”) (i.e., sessions prescribed according to the “National Law of Education”; 2 × 55 min/week); (2) increased exercise volume (“experimental group 1”; “EG1”) (i.e., 4 × 55 min/week); and (3) increased exercise volume and intensity (“EG2”) (i.e., more intensive 55 min sessions; 4 times/week). In general, the EG2 group improved more than the control group and the EG1 group in several cognitive functions and domains (i.e., non-verbal and verbal skills, abstract reasoning, and spatial and numerical skills), which also indicates that the simple increase in frequency of physical education sessions (e.g., from 2 to 4 times/week) is not sufficient to promote positive effects on academic achievement (at least when these increases are not accompanied by concomitant changes in exercise intensity). With that said, teachers and policy makers should be aware that more intensive physical activities are required to achieve greater gains in academic performance.

The positive effects of school-based physical activity programs were larger for mathematics skills, with sub-group analyses revealing no significant effects for language- and reading-related abilities and composite scores (Figure 2). Accordingly, Mavilidi et al. [43] reported no improvements in cognitive function and some specific learning outcomes (i.e., grammar skills) after examining the effects of a 4-week school-based program that integrated physical activity into English lessons in children aged 11–12 years. Likewise, Shore et al. [70] did not find any differences in academic achievement (assessed by composite scores) after comparing the effects of a “school-based pedometer intervention” (i.e., a sample of sixth-grade students who received instructions to achieve 3200 steps during physical education classes and a total of 10,000 daily steps for 6 weeks) with the effects of “standard physical education” (i.e., students who participated in regular physical education classes). Despite the short duration of the abovementioned studies (i.e., ≤6 weeks), their findings contrast with previous investigations with similar time periods and aims, which assessed the effects of physical activity on mathematics skills. For instance, a 6-week study comparing the effects of three different strategies (i.e., “conventional math teaching” versus math teaching combined with “fine” or “gross” motor tasks) showed that participation in the math classes that integrated more vigorous physical activities (i.e., inter-limb movements such as skipping, throwing, and one-legged balancing) could positively influence mathematical achievements in pre-adolescent children [45]. Vazou et al. [62] observed a similar trend in an 8-week intervention that tested the effects of physical activity (combined with math) in fourth- and fifth-grade students. In that study, the increase in math performance was significantly larger in the “integrated physical activity group” (compared with that of the control group, who participated in traditional math classes). From these results, it is possible to infer that (1) improvements in math skills are more expected and consistent than in other skills (e.g., improvements in language or reading abilities) after short- or mid-term (≤8 weeks) physical education programs and (2) the integration of physical activity into regular classes (especially mathematics) could be an effective strategy to enhance learning in school-aged students.

In fact, the benefits of physical education for math learning appear to be more pronounced even in long-term studies. In this sense, Lubans et al. [53] demonstrated the positive (small-to-medium) effects of a 15-month “multicomponent physical activity program” (including physical education classes with moderate-to-vigorous exercises) on mathematics performance in an investigation conducted with hundreds of eighth-grade students. Mullender-Wijnsma et al. [57] confirmed this tendency after analyzing the results of a 2-year intervention that integrated physical activities into math and spelling lessons in almost 500 s- and third-grade students from 12 elementary schools. Curiously, in that study, both spelling and general math skills increased (compared with the control group); nevertheless, the positive effect on mathematics performance (revealed by the “child academic monitoring system test”) was already detected after one year of intervention, whereas spelling ability was only enhanced after two years. Together, these findings suggest that the improvements in mathematics learning obtained through the implementation of systematic physical education programs might be superior, at least when compared with language- and reading-related abilities. This also holds true for analyses integrating a variety of learning scores (i.e., composite scores) and agrees with the main outcome of this systematic review, which highlights the positive influence of physical education programs on mathematics achievement.

5. Conclusions

In general, the positive effects of school-based physical education programs on academic performance are not uniform and seem to be higher for mathematics skills. These effects may be optimized with the integration of multi-component exercise schemes into regular classes of different education levels as an efficient and alternative learning strategy. The concomitant prescription of “gross motor tasks” and more intensive (and appropriate) physical activities is also recommended in an attempt to maximize students’ learning outcomes. In addition to the recognized benefits of systematic exercise on both health and psychological well-being, the implementation of evidence-based physical education programs in distinct school settings emerges as a promising strategy to increase overall academic achievement in school-aged students.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.L., N.P.M., M.B.F., V.B., and L.A.P.; methodology, I.L. and L.A.P.; formal analysis, I.L. and L.A.P.; investigation, I.L. and L.A.P.; data curation, I.L. and L.A.P.; writing—original draft preparation, I.L. and L.A.P.; writing—review and editing, I.L. and L.A.P.; visualization, I.L., N.P.M., M.B.F., V.B., and L.A.P.; supervision, I.L. and L.A.P.; project administration, I.L., N.P.M., M.B.F., V.B., and L.A.P.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Baker, B.; Castelli, D. Physical activity and sedentary behavior influences on executive function in daily living. In Neuroergonomics; Chang, S.N., Ed.; Springer: Champaign, IL, USA, 2020; pp. 161–181. [Google Scholar]

- Bermúdez, V.J.; Rojas, J.J.; Córdova, E.B.; Añez, R.; Toledo, A.; Aguirre, M.A.; Cano, C.; Arraiz, N.; Velasco, M.; López-Miranda, J. International physical activity questionnaire overestimation is ameliorated by individual analysis of the scores. Am. J. Ther. 2013, 20, 448–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Cesare, M.; Sorić, M.; Bovet, P.; Miranda, J.J.; Bhutta, Z.; Stevens, G.A.; Laxmaiah, A.; Kengne, A.P.; Bentham, J. The epidemiological burden of obesity in childhood: A worldwide epidemic requiring urgent action. BMC Med. 2019, 17, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Middelbeek, L.; Breda, J. Obesity and sedentarism: Reviewing the current situation within the who european region. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2013, 2, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathers, C.; Stevens, G.; Mascarenhas, M. Global Health Risks: Mortality and Burden of Disease Attributable to Selected Major Risks; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Normansell, R.A.; Holmes, R.; Victor, C.R.; Cook, D.G.; Kerry, S.; Iliffe, S.; Ussher, M.; Ekelund, U.; Fox-Rushby, J.; Whincup, P. Op23 exploring the reasons for non-participation in physical activity interventions: Pace-up trial qualitative findings. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2014, 68, A14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Oliver, A.J.; Martín García, C.; Gálvez Ruiz, P.; González-Jurado, J.A. Mortality and economic expenses of cardiovascular diseases caused by physical inactivity in spain. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2018, 18, 1420–1426. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, J.A. Physical inactivity: Associated diseases and disorders. Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2012, 42, 320–337. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases 2014; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R.; Pattisapu, A.; Emery, M.S. US physical activity guidelines: Current state, impact and future directions. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 30, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, B.X.; Dang, K.A.; Le, H.T.; Ha, G.H.; Nguyen, L.H.; Nguyen, T.H.; Tran, T.H.; Latkin, C.A.; Ho, C.S.H.; Ho, R.C.M. Global evolution of obesity research in children and youths: Setting priorities for interventions and policies. Obes. Facts 2019, 12, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arancibia, B.A.V.; Silva, F.C.; Dos Santos, P.D.; Gutierres Filho, P.J.B.; Silva, R. Prevalence of physical inactivity among adolescents in brazil: Systematic review of observational studies. Phys. Educ. Sport 2015, 34, 331–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gómez, S.F.; Homs, C.; Wärnberg, J.; Medrano, M.; Gonzalez-Gross, M.; Gusi, N.; Aznar, S.; Cascales, E.M.; González-Valeiro, M.; Serra-Majem, L.; et al. Study protocol of a population-based cohort investigating physical activity, sedentarism, lifestyles and obesity in spanish youth: The pasos study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e036210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Nascimento, A.C.S.; Suano-Souza, F.I.; Sarni, R.O.S. Extracurricular physical activities practiced by children: Relationship with parents’ nutritional status and level of activity. Nutrire 2019, 44, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCaul, K.; Baker, J.; Yardley, J.K. Predicting substance use from physical activity intensity in adolescents. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 2004, 16, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pate, R.R.; Long, B.J.; Heath, G.W. Descriptive epidemiology of physical activity in adolescents. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 1994, 6, 434–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clarke, W.R.; Lauer, R.M. Does childhood obesity track into adulthood? Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 1993, 33, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, T.; Magnussen, C.G.; Schmidt, M.D.; Ukoumunne, O.C.; Ponsonby, A.L.; Raitakari, O.T.; Zimmet, P.Z.; Blair, S.N.; Thomson, R.; Cleland, V.J.; et al. Decline in physical fitness from childhood to adulthood associated with increased obesity and insulin resistance in adults. Diabetes Care 2009, 32, 683–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bouchard, C.; Després, J.P. Physical activity and health: Atherosclerotic, metabolic, and hypertensive diseases. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 1995, 66, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kravitz, L. The 25 most significant health benefits of physical activity and exercise. IDEA Fit. J. 2007, 4, 54–63. [Google Scholar]

- Biddle, S.; Fox, K.R.; Boutcher, S.H. Physical Activity and Psychological Well-Being; Routledge: London, UK, 2000; Volume 552. [Google Scholar]

- Calfas, K.J.; Taylor, W.C. Effects of physical activity on psychological variables in adolescents. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 1994, 6, 406–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkinos, P. Physical activity, health benefits, and mortality risk. ISRN Cardiol. 2012, 2012, 718789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Malina, R.M. Physical activity and fitness: Pathways from childhood to adulthood. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2001, 13, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Floody, P.; Guzmán-Guzmán, I.P.; Caamaño-Navarrete, F.; Jerez-Mayorga, D.; Zulic-Agramunt, C.; Cofré-Lizama, A. Depression is associated with lower levels of physical activity, body image dissatisfaction, and obesity in chilean preadolescents. Psychol. Health Med. 2021, 26, 518–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacka, F.N.; Pasco, J.A.; Williams, L.J.; Leslie, E.R.; Dodd, S.; Nicholson, G.C.; Kotowicz, M.A.; Berk, M. Lower levels of physical activity in childhood associated with adult depression. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2011, 14, 222–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomson, L.M.; Pangrazi, R.P.; Friedman, G.; Hutchison, N. Childhood depressive symptoms, physical activity and health related fitness. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2003, 25, 419–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, S.; Kalak, N.; Gerber, M.; Clough, P.J.; Lemola, S.; Sadeghi Bahmani, D.; Pühse, U.; Holsboer-Trachsler, E. During early to mid adolescence, moderate to vigorous physical activity is associated with restoring sleep, psychological functioning, mental toughness and male gender. J. Sports Sci. 2017, 35, 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doré, I.; Sylvester, B.; Sabiston, C.; Sylvestre, M.P.; O’Loughlin, J.; Brunet, J.; Bélanger, M. Mechanisms underpinning the association between physical activity and mental health in adolescence: A 6-year study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Slater, A.; Tiggemann, M. The contribution of physical activity and media use during childhood and adolescence to adult women’s body image. J. Health Psychol. 2006, 11, 553–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, J.E.; Hillman, C.H.; Castelli, D.; Etnier, J.L.; Lee, S.; Tomporowski, P.; Lambourne, K.; Szabo-Reed, A.N. Physical activity, fitness, cognitive function, and academic achievement in children: A systematic review. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2016, 48, 1223–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, A.; Corrales, F.R.G.; Martins, J.; Catunda, R.; Sarmento, H. Association between physical education, school-based physical activity, and academic performance: A systematic review. New Trends Phys. Educ. Sport Recreat. 2017, 31, 316–320. [Google Scholar]

- Zach, S.; Shoval, E.; Lidor, R. Physical education and academic achievement—Literature review 1997–2015. J. Curric. Stud. 2017, 49, 703–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (prisma-p) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moher, D.; Cook, D.J.; Eastwood, S.; Olkin, I.; Rennie, D.; Stroup, D.F. Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: The quorom statement. Br. J. Surg. 2000, 87, 1448–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Bueno, C.; Pesce, C.; Cavero-Redondo, I.; Sánchez-López, M.; Garrido-Miguel, M.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V. Academic achievement and physical activity: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2017, 140, e20171498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bedard, C.; St John, L.; Bremer, E.; Graham, J.D.; Cairney, J. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the effects of physically active classrooms on educational and enjoyment outcomes in school age children. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0218633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Higgins, J.P.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Higgins, J.P.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Jüni, P.; Moher, D.; Oxman, A.D.; Savovic, J.; Schulz, K.F.; Weeks, L.; Sterne, J.A. The Cochrane collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011, 343, d5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ardoy, D.N.; Fernández-Rodríguez, J.; Jiménez-Pavón, D.; Castillo, R.; Ruiz, J.; Ortega, F. A physical education trial improves adolescents’ cognitive performance and academic achievement: The edufit study. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2014, 24, e52–e61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Hermoso, A.; Hormazábal-Aguayo, I.; Fernández-Vergara, O.; González-Calderón, N.; Russell-Guzmán, J.; Vicencio-Rojas, F.; Chacana-Cañas, C.; Ramírez-Vélez, R. A before-school physical activity intervention to improve cognitive parameters in children: The active-start study. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2020, 30, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavilidi, M.F.; Lubans, D.R.; Eather, N.; Morgan, P.J.; Riley, N. Preliminary efficacy and feasibility of the “thinking while moving in English”: A program with integrated physical activity into the primary school english lessons. Children 2018, 5, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sallis, J.F.; Lewis, M.; McKenzie, T.L.; Kolody, B.; Marshall, S.; Rosengard, P. Effects of health-related physical education on academic achievement: Project spark. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 1999, 70, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, M.M.; Lind, R.R.; Geertsen, S.S.; Ritz, C.; Lundbye-Jensen, J.; Wienecke, J. Motor-enriched learning activities can improve mathematical performance in preadolescent children. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Davis, C.L.; Tomporowski, P.D.; McDowell, J.E.; Austin, B.P.; Miller, P.H.; Yanasak, N.E.; Allison, J.D.; Naglieri, J.A. Exercise improves executive function and achievement and alters brain activation in overweight children: A randomized, controlled trial. Health Psychol. 2011, 30, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Donnelly, J.E.; Hillman, C.H.; Greene, J.L.; Hansen, D.M.; Gibson, C.A.; Sullivan, D.K.; Poggio, J.; Mayo, M.S.; Lambourne, K.; Szabo-Reed, A.N.; et al. Physical activity and academic achievement across the curriculum: Results from a 3-year cluster-randomized trial. Prev. Med. 2017, 99, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fakri, N.F.N.; Hashim, H.A. The effects of integrating physical activity into mathematic lessons on mathematic test performance, body mass index and short term memory among 10 year old children. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2020, 20, 425–429. [Google Scholar]

- Fedewa, A.L.; Ahn, S.; Erwin, H.; Davis, M.C. A randomized controlled design investigating the effects of classroom-based physical activity on children’s fluid intelligence and achievement. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2015, 36, 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Hannan, P.; Xiang, P.; Stodden, D.F.; Valdez, V.E. Video game-based exercise, latino children’s physical health, and academic achievement. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2013, 44, S240–S246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hraste, M.; De Giorgio, A.; Jelaska, P.M.; Padulo, J.; Granić, I. When mathematics meets physical activity in the school-aged child: The effect of an integrated motor and cognitive approach to learning geometry. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Layne, T.; Yli-Piipari, S.; Knox, T. Physical activity break program to improve elementary students’ executive function and mathematics performance. Education 2021, 49, 583–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubans, D.R.; Beauchamp, M.R.; Diallo, T.M.O.; Peralta, L.R.; Bennie, A.; White, R.L.; Owen, K.; Lonsdale, C. School physical activity intervention effect on adolescents’ performance in mathematics. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2018, 50, 2442–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavilidi, M.F.; Drew, R.; Morgan, P.J.; Lubans, D.R.; Schmidt, M.; Riley, N. Effects of different types of classroom physical activity breaks on children’s on-task behaviour, academic achievement and cognition. Acta Paediatr. 2020, 109, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mavilidi, M.F.; Okely, A.; Chandler, P.; Louise Domazet, S.; Paas, F. Immediate and delayed effects of integrating physical activity into preschool children’s learning of numeracy skills. J. Exp. Child. Psychol. 2018, 166, 502–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavilidi, M.F.; Vazou, S. Classroom-based physical activity and math performance: Integrated physical activity or not? Acta Paediatr. 2021, 110, 2149–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullender-Wijnsma, M.J.; Hartman, E.; De Greeff, J.W.; Doolaard, S.; Bosker, R.J.; Visscher, C. Physically active math and language lessons improve academic achievement: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics 2016, 137, e20152743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Polo-Recuero, B.; Moreno-Barrio, A.; Ordonez-Dios, A. Physically active lessons: Strategy to increase scholars’ physical activity during school time. Rev. Int. Cien. Dep. 2020, 16, 342–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinto Romani, A.; Klausen, T.B. Physical activity and school performance: Evidence from a danish randomised school-intervention study. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2017, 61, 479–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoval, E.; Sharir, T.; Arnon, M.; Tenenbaum, G. The effect of integrating movement into the learning environment of kindergarten children on their academic achievements. Early Child. Educ. J. 2018, 46, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarp, J.; Domazet, S.L.; Froberg, K.; Hillman, C.H.; Andersen, L.B.; Bugge, A. Effectiveness of a school-based physical activity intervention on cognitive performance in danish adolescents: Locomotion-learning, cognition and motion—A cluster randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0158087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vazou, S.; Skrade, M.A.B. Intervention integrating physical activity with math: Math performance, perceived competence, and need satisfaction. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2017, 15, 508–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, A.J.L.; Timperio, A.; Brown, H.; Hesketh, K.D. A pilot primary school active break program (acti-break): Effects on academic and physical activity outcomes for students in years 3 and 4. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2019, 22, 438–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resaland, G.K.; Aadland, E.; Moe, V.F.; Aadland, K.N.; Skrede, T.; Stavnsbo, M.; Suominen, L.; Steene-Johannessen, J.; Glosvik, Ø.; Andersen, J.R.; et al. Effects of physical activity on schoolchildren’s academic performance: The active smarter kids (ask) cluster-randomized controlled trial. Prev. Med. 2016, 91, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Riley, N.; Lubans, D.R.; Holmes, K.; Morgan, P.J. Findings from the easy minds cluster randomized controlled trial: Evaluation of a physical activity integration program for mathematics in primary schools. J. Phys. Act. Health 2016, 13, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahamed, Y.; Macdonald, H.; Reed, K.; Naylor, P.J.; Liu-Ambrose, T.; McKay, H. School-based physical activity does not compromise children’s academic performance. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2007, 39, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagins, M.; Rundle, A. Yoga improves academic performance in urban high school students compared to physical education: A randomized controlled trial. Mind Brain Educ. 2016, 10, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, R.A.; Soares, F.C.; Bezerra, J.; de Barros, M.V.G. Effects of a physical education intervention on academic performance: A cluster randomised controlled trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mead, T.; Scibora, L.; Gardner, J.; Dunn, S. The impact of stability balls, activity breaks, and a sedentary classroom on standardized math scores. Phys. Educ. 2016, 73, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shore, S.M.; Sachs, M.L.; DuCette, J.P.; Libonati, J.R. Step-count promotion through a school-based intervention. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2014, 23, 402–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto-Escalona, T.; Martinez-de-Quel, O. Ten minutes of interdisciplinary physical activity improve academic performance. Apunts Educ. Fís. Esports 2019, 138, 82–94. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).