Abstract

This study examined the leadership approach to child health and wellbeing within the early-years sector; it drew upon the evidence from thirty-two practitioners and ten nursery managers. Practitioners evidenced the challenges in recognising the signs and symptoms of low wellbeing and in monitoring progress. A constructivist paradigm enabled qualitative data to be collected from an interactive questionnaire and three focus groups of nursery managers. Analysis was supported by two wellbeing models: the PERMA model (Positive Emotion, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning, and Accomplishment) and the SHANARRI wheel (Safe, Healthy, Achieving, Nurtured, Active, Respected, Responsible, Included). The findings accentuated the lack of confidence of practitioners in identifying the precursors of health and wellbeing, and their ability to monitor the progress to support children. In conclusion, a clear definition of health and wellbeing should be adopted by managers; their leadership is vital to support the training of practitioners sharing their knowledge and experience to less-qualified staff. The main issues to transpire highlighted that clear mandatory guidance should be available for early-years practitioners, and the creation of a bespoke early-years model to measure child health and wellbeing.

1. Introduction

The town of Blackpool is a seaside resort on the coast of Lancashire, England which hosts an estimated transient population of 141,500 [1]. The current data report by Public Health England [2] rates Blackpool as conveying one of the most deprived authorities in England: about 52% (8400) of children live in low-income families. The report states that early-years children living in the local area are severely impacted by the social determinates of the area and the impact of poverty.

The community indicates a high rate of unemployment, child protection cases, and domestic abuses. Contemporary figures further evidence that Blackpool transcends the national averages due to the high rates of drug and alcohol abuse in the town [2]. The National Children Bureau Publication “Great Expectations” evaluates a 50-year major study which explores the experiences of children from disadvantaged and poor backgrounds [3]. Further contemporary views by the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC) state that one in four children are living in poverty, and this has a lasting impact on their wellbeing and emotional development [4].

Current UK statutory guidance within the Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS) [5], advises that practitioners should work to nurture children’s individual well-being and that there are clear correlations between the emotional aspect and child development. Additionally, Seaman and Giles (2019) acknowledge that emotional well-being plays a fundamental part in the relationships that early-years children make and the way that they communicate with the world around them [6].

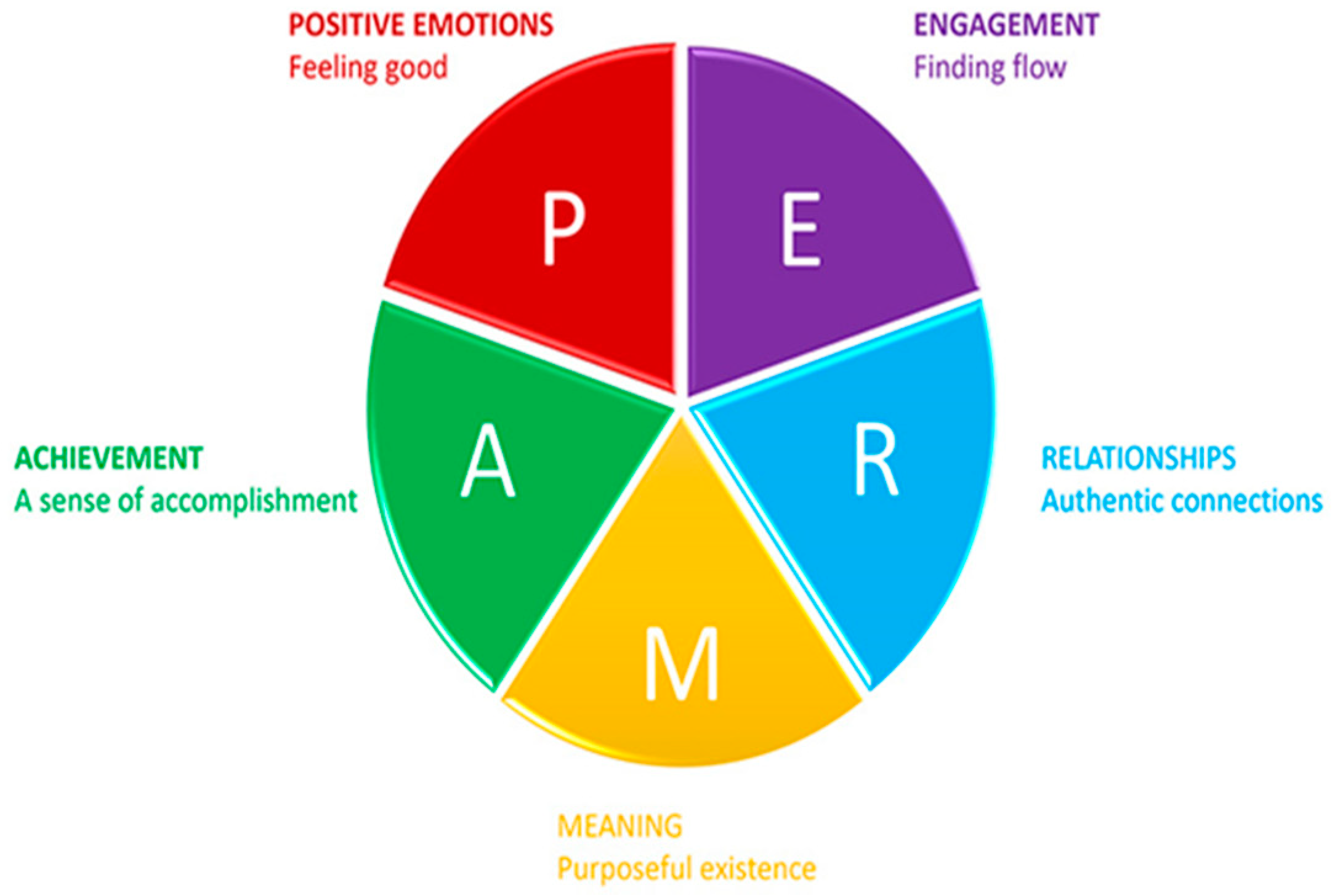

The role of early-years practitioners is vital in supporting children’s emotional wellbeing. The workforce must feel confident and proficient at recognising low health and wellbeing and the impact this has on child development. Staff must feel supported within their provisions by their managers to tackle the challenges faced when supporting child wellbeing. For early intervention to occur, a huge responsibility falls on early-years staff to identify and promote the positive health and wellbeing of children. Practitioners must identify and monitor the child’s wellbeing to ensure that progress and improvement is being made and measure the child’s level with the appropriately selected tool to monitor emotional well-being and involvement. Some settings utilise the Leuven Scale [7] to assess a child’s involvement and wellbeing; it uses a five-point scale to measure the child’s well-being and involvement. The tool allows staff to make judgement using the scale at regular intervals during the year. Each child is scored by the practitioner using the five grades: extremely low, low, moderate, high, and extremely high. Additionally, very few local settings use the SHANARRI wheel [8], which is effectively used in Scottish practice; the tool supports the practitioner by using eight wellbeing indicators which are used to assess the child and ascertain whether there is a need for support. However, from a global perspective, the Australian PERMA wellbeing model [9] used in early-years practice focuses on emotions, relationships, and achievement as well as the five core elements of wellbeing and happiness. The model forges the link between early childhood and positive psychology, recognising play as a vehicle that drives learning and happiness, thus building confidence and curiosity in early childhood.

All these wellbeing models promote the holistic philosophies placing the child at the centre of the observation [10], which replicated the historical ideologies of Froebel (1837) and Montessori (1967) arguing that the child should be at the centre of their overall learning and development [6]. The current UK early-years practice states, in the revised Early Years Framework Stage [5], that this is vital for early-years children to lead happy, healthy lives which will support them to develop their cognitive stages of development. Building strong, supportive relationships assists the child to comprehend how they develop sustainable bonds with others; this further supports them to build their confidence and manage their emotions, thus developing a positive image of themselves.

For the purpose of this research, several wellbeing tools were examined and scrutinized the established Leuvan Scale [7], Stirling Children’s Wellbeing Scale [6], the SHANARRI wheel [8], and PERMA model [9]. The Scottish government’s focus on the Getting It Right for Every Child [8] agenda saw the introduction of the SHANARRI wheel being adopted in mandatory early-years practice. This holistic assessment of the child supports the practitioner to identify key elements that contribute to child wellbeing. Similar principles are visible in the PERMA model, which values the influences of core elements that impact overall child development.

Both the SHANARRI wheel [8] and PERMA model [9] were used to analyse the findings from the interactive questions and the focus groups; the models were used as frameworks to conduct and evaluate the findings to form the discussion. Questions were raised as to whether the tools available are detailed and robust enough, and whether they allow early-years practitioners to make a judgement and measure the wellbeing adequately.

This study critically examined the topic of child health and wellbeing within thirty-two early-years settings which evaluated the role of the practitioner in first to recognise the signs of low child-health and wellbeing, and secondly, to measure the child’s progress. The preliminary findings from the questionnaires formed the themes for the focus groups, where 10 nursery managers discussed the leadership and management of their individual provisions regarding wellbeing. The focus groups with ten experienced early -years leaders/nursery managers explored child health and wellbeing in their settings; the meetings concentrated on their understanding of wellbeing and how they lead and manage staff within early-years provision, focusing on what wellbeing tools they favour and whether staff are confident using the tool. Finally, staff had the opportunity to access training to support them to identify child health and wellbeing.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Definition of Wellbeing

UNICEF [11] defines child wellbeing as an approach that values the happiness and satisfaction of every child, regardless of their socio-economic play. Well-being is related to self-realisation and self-acknowledgment of the present and forthcoming competence set for children. Furthermore, UNICEF’s (2019) international research simply defines wellbeing as how happy, healthy, and satisfied children are [12]. Focus presented by the Scottish government (2006) [8] and UN Convention on the Rights of the Child Bill (2020) [12] places the value on children’s rights and their wellbeing advising the power of joined up decision-making. The UNCRC supports public authorities in a bid to develop the rights of wellbeing for children and young people [11]. Similar views are presented by Seaman and Giles [6], who define child wellbeing as the interplay between children’s rights, healthy development, and their freedom to exercise those rights, also stating that they are influenced by issues at the micro level and are surrounded by the social structures of the wider community. However, in comparison, the United Kingdom government publication discusses child wellbeing simply as the quality of a child’s life, which is potentially measured by an individual’s achievement and fulfilling of social and personal goals [10]. This research report evidences the socio-economic influences that impact on child health and wellbeing, promoting the support of holistic intervention to support the child succeeding.

The current publication from The Children Society [13] outlines wellbeing as an ‘umbrella term’ that should be accompanied by a collection of appropriate indicators that can be used to build up a true picture of the child. Dodge et al. [14] state that there are several opposing approaches to defining wellbeing, and it is extremely problematic to identify between a hedonic belief compared with the view of achieving and flourishing. Sointu [15] disagrees and defines wellbeing as a ‘notion’ in society and a concept that impacts a person’s happiness; they also discuss the development of wellbeing as an evolving notion. There is

“a lack of definition in much health policy and practice typically leaves the term ‘well-being’ as an open-ended, catch-all category”(p. 349) [15]

Furthermore, Morrow and Mayall (2009) discuss there is a lack of clarity surrounding a definition of wellbeing, and there is a significant absence due to society’s portrayal of wellbeing, which is affected by cultural opinions [16]. In agreement, Thompson and Aked (2009, p. 11) define wellbeing as “intangible, difficult to define and even harder to summaries” [17]. Additionally, Danby and Hamilton (2016) argue that the knowledge of wellbeing has developed since 2005, and the change in perception is evolving following research and studies; the views on wellbeing are more educated and more clearly defined [18].

However, Coles et al.’s (2015) research focuses on the challenge of leadership within early-years intervention and the task of improving child health and wellbeing within the sector [19]. The systemic review highlights how adverse early-life experiences and health inequalities, such as poverty, can have lasting effects on a child development. The paper further emphasises the importance of how early-years leaders and managers review and create a framework to focus on

“what works, for whom, in what circumstances and why”(Coles, et al.; 2015; p. 4). [19]

It is apparent there is a challenge in defining wellbeing and the need to generate a clear, comprehensive definition [20,21]. For the purposes of this study, wellbeing will be viewed as a physical, emotional, and social state and will focus on the interaction and successful relationships with others. Furthermore, the contributing external factors that impact on a child’s happiness and contentment will also be analysed. The next section will focus on the challenge of measuring health and wellbeing.

2.2. Measuring Child Health and Wellbeing

Scottish practice favours the existing SHANARRI wheel (Figure 1) to measure wellbeing, which draws on the principles of how to assess child health and wellbeing [8]. The model is used with early-years practice and places the importance of feeling safe, having respect, and love. The eight wellbeing indicators highlighted in the model assist early-years practice to ensure that they value every child as unique and understand that there is no level that a child should achieve in relation to their wellbeing, but each child should be supported to achieve their full potential. The tool allows for consistency across practice, allowing early-years practice to measure child wellbeing at set times. Similar ideologies are highlighted in the UK government’s Getting It Right for Every Child (GIRFEC) approach, which advocates that every child should be supported to reach their full potential, regardless of their socio-economic background [5]. Both UK and Scottish practice highlight the importance of efficient leadership within early-years provision to guide and support early-years workers in measuring wellbeing.

Figure 1.

SHANARRI wellbeing wheel [8].

Currently, within some UK early-years provisions, the Leuven scales [7] are used to measure health and wellbeing. The tool allows the practitioner to grade the child on their wellbeing and involvement through observations. The scales place the child at the centre of their learning and promote the holistic view of development. The scales replicate the historical theory of Froebel (1837) and Montessori (1967), believing that a child should be placed holistically at the centre of their learning and supported though interaction and engagement [7]. Additional theoretical perspectives such and Vygotsky (1978) further endorse the principles that a child’s cognitive development occurs with interaction with the world around them. However, Piaget (1950) disputed these views and believes that a child must pass through set stages of cognition to expand their development but placed no focus on holistic development. Furthermore, the views of Morrow and Mayall (p. 227) state that:

“attempts to measure children’s well-being are problematic because they fail to incorporate an analysis of broader contextual structural and political factors.”[16].

Finally, the views of Seligman (2012) promote the PERMA model of wellbeing (Figure 2); its five core elements measure emotions, relationships, and the achievement of wellbeing and happiness [9]. The model is a multidimensional tool to wellbeing that consist of five positive pillars: emotion, engagement, relationships, meaning, and accomplishment. Parallels can be seen with Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development (1978), where children progress at the psychological stage, advancing their emotional wellbeing and social development [7].

Figure 2.

PERMA model of wellbeing [9].

2.3. Leadership of Wellbeing

Current UK guidance within early-years practice [5] indicates that nursery managers must be equipped to support practitioners within their team with the daily challenges of supporting emotional development and wellbeing. Similar recognition is presented in the views of Dodge et al., recognising that many early-years practitioners have little training or qualifications to support them with wellbeing and rely on management to steer and guide them in the challenges to support child health and wellbeing [14]. The work of Zabeli and Gjelaj discusses the importance of strong, direct leadership within early-years provision and values the importance of clear guidance for practitioners in relation to supporting child wellbeing. The quality of provision is paramount in supporting the nurturing of positive wellbeing within nursery provision; staff need to be trained and supported to recognise and measure the signs of positive wellbeing [22]. The views of Cole et al. acknowledge that nursery leaders and managers must appreciate the need for early-years practitioners to feel confident in their abilities to support child health and wellbeing, further acknowledging the need for practitioners to receive appropriate training to build their capabilities in working with the evolving issues within early-years practice [19].

2.4. International Focus

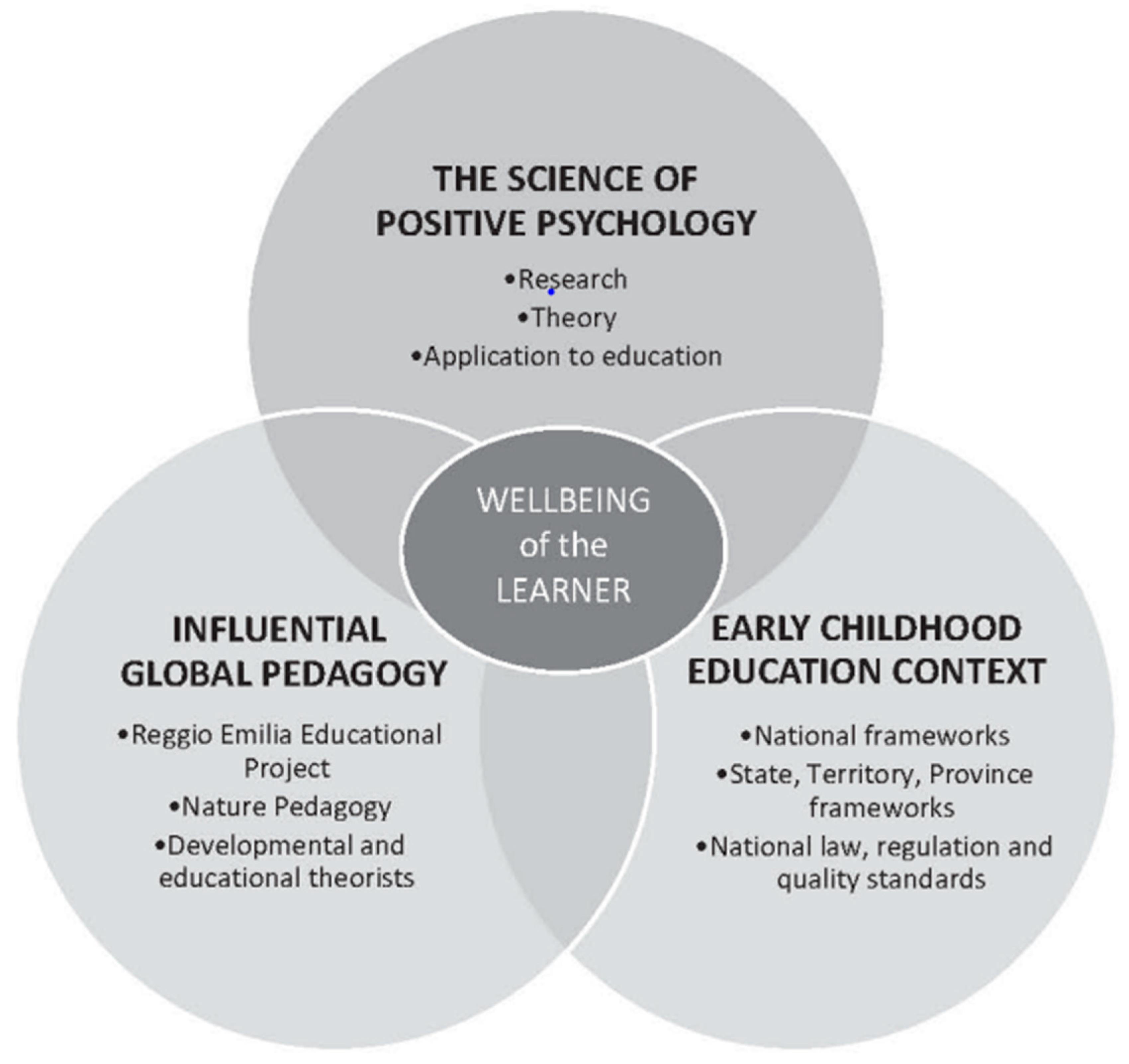

Early-childhood Australian practice supports the work of Baker, Green, and Falecki [23], who portray the link between purposeful pedagogy, education, and positive psychology (Figure 3) and the purpose of early education in shaping early child development. Placing the emphasis on the importance of positive intervention to enhance the synergy between pedagogy and psychology within the early-years sector. The paper forges the links between intervention and creative, engaging teaching that supports the child to build their own resilience and thus develop their emotional intelligence.

Figure 3.

Wellbeing synergies: global pedagogy, positive psychology, and early childhood education [24].

Furthermore, similarities are highlighted within Kosovo’s early-years practice within a current qualitative study conducted by Zabeli and Gjelaj [24], which highlights that all early-years activities within settings should embrace inclusive education, and wellbeing should align with all element of happiness and achievement. Moreover, research in Hong Kong further values the need for happiness and appraises the effects of play [25]. The study utilises a child emotional manifestation scale (1–5 scales) to measure emotions and recognises interaction, facial expression, and vocalization.

Lastly, the Department for Education’s (2018) International Early Learning and Child Well-being Study (IELS) further analyses wellbeing in a global context [10]. The international study allows for comparison to be made relating to child development in England with children in other countries. The study focuses on aspects of child development and deliberates the educational outcomes that broaden a child’s wellbeing. The ongoing findings have recently been presented in the OECD’s 2020 publication, studying five-year-old children living in England (UK), Estonia, and the United States of America [26]. The study presents comparative data on the factors that could delay a child’s early learning. The research directly assessed the social and emotional skills of the children and self-regulation of emotions. The outcomes from the OECD validate that early development and wellbeing are inter-related and equally important. For a child to feel happy and thrive, they must be reinforced by strong, solid foundations from the main carer and family surrounding them. The guidance promotes that children should be educated on their cultural and community environment, and these continuous interactions nurture their identity and wellbeing [26].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Methodological Approach

The current research took place in a further education and higher education college setting throughout 2020. The researcher had access to all three levels of students, who possess level three, four, and five qualifications. The sample for the research was taken from level three and four students studying a foundation degree in Early Childhood Studies and the level five BA Hons in Early Childhood Studies. Many discussions took place relating to child health and wellbeing within weekly sessions. Students at every level recognise the importance of being able to recognise and record child health and wellbeing using different appraisal tools. A constructive paradigm was identified which allowed for knowledge to be created and meaning to be place to the early-years experiences; this will assist practitioners to reflect on their practice and construct their perception of child health and wellbeing and the world around them [27,28].

An interactive Google Forms questionnaire has gathered the findings from thirty-two early-years students studying at levels four, five, and six. Furthermore, the methodology has supported the collecting of early-years managers’ views from themed focus groups that discussed and worked together to improve practice in the local area.

3.2. Interactive Google Form Questionnaire

The students completed an open-ended questionnaire with five questions, with their highest early-years qualification being identified. The qualitative method took the form of a questionnaire/survey allowing the respondents much more freedom and flexibility to provide their responses [29]. A virtual Google Forms questionnaire was created that participants could access easily through Microsoft Teams; the survey was interactive and easy to follow. The questionnaires to students provided a variety of opinions and views about their knowledge regarding child wellbeing and how they recognise and record their findings. The approach allowed for few quantitative analyses of the data and the process of coding themes. Thought was given to the benefits of applying a Likert scale technique, which will allows for the respondents’ views to be numerically coded; Flewitt and Ang [30] advise that the Likert technique is a valuable method for participants to respond simply. However, Gorad [31] disputes this belief, arguing that utilising this method does not give a true measure of the participants due to the fact that the method only gives the limited option of choice for the respondent. After consideration, a decision was made not to adopt this method as narrative comments were more beneficial to the study.

It was imperative to follow ethical principles to respect the participants; furthermore, their integrity should be protected at all times of their involvement. The confidentiality of those being consulted was paramount; no names were used in the study and all participants remained anonymous. Informed voluntary consent was provided from all of the early-years participant discussions that took place, and they were further advised that they had the right to withdraw at any point.

3.3. Research Question

The initial research question for the study critically evaluated: “How do early-years practitioners identify, record, and support child health and wellbeing in the deprived area of Blackpool”?

The study gathered early-years practitioners’ views at different levels of qualification and experiences to try and ascertain what their knowledge was and how confident they felt in the setting. I was able to collect their experiences as to what signs identify low health and wellbeing and how would they support this.

Survey of thirty-two early-years practitioners’ views

Firstly, the overarching enquiry focused on practitioners and their perspectives of child wellbeing. Then, their level of qualifications and how long they had been working in the sector was established.

The sub-questions:

- What do you understand about the term ‘child health wellbeing’?

- In your experience, when working with early-years children, what signs identify low health and wellbeing?

- What tools (if any) do you use to monitor and measure child health and wellbeing?

- Do you feel you are qualified and experienced to support child health and wellbeing in your day-to-day role?

Focus group of ten nursery managers

Secondly, a focus group was conducted with ten nursery leaders all working within a leadership role to gather their views on leadership within their settings. The managers were identified from different areas of the town in an attempt to gather reliable comments and data, ensuring the validity of the research by robustly measuring the methods [28]. The questions discussed in the group were divided into three themed focus meetings addressing the themes identified from the initial responses gathered from 32 early-years practitioners.

Meeting one

What do you understand by the term ‘wellbeing’?

How do you assist and lead staff to support child health and wellbeing in your setting?

Meeting two

What wellbeing tools do you use in your setting?

Do you think the leadership of staff enables them to feel confident in completing the wellbeing tool?

Meeting three

Have staff accessed training about supporting health and wellbeing?

How confident are you in supporting your staff team in supporting child health and wellbeing?

The focus groups concluded with a discussion of how as early-years practitioners we can develop the support we offer for child health and wellbeing within the setting; how we can make changes to our further practice, recognising the social determinates of the local area and the impact this has on child development; and how leaders within the sector can support their team to develop to support wellbeing in their setting.

The research has been collated and analysed using the contributions from an interactive Google Forms questionnaire, asking six questions to thirty-two respondents working within the sector and themed focus groups of ten experienced nursery managers. The findings evidenced clearly that a number of emerging themes have been highlighted from the responses from both methods.

3.4. Thematic Analyses

Thematic analyses allowed for the identifying, analysing, and reporting of themes for both methods used. Braun and Clarke [32] delineate thematic analysis as an approach to recognising, analysing, and presenting patterns within datasets. The process is best described as an umbrella term that is used to analyse qualitative statistics that present recognised themes [33]. The process was used to gain some focus that can be discussed and addressed after the research is complete. The focus group was a catalyst for improving practices within the sector and will be the starting point for managers to recognise the themes and address the issues in their setting (Table 1). The following themes emerged from the study (Table 2): there was no clear definition of wellbeing, and participants lacked clarity in relation to their understanding of wellbeing; no one tool was favoured to measure and monitor child wellbeing; all participants highlighted the need for more training and qualifications to upskill them for the current challenge of supporting child health and wellbeing.

Table 1.

Coding of data to form thematic analyses from early-years practitioners’ questionnaires.

Table 2.

Coding of data from themed focus groups.

4. Analysis and Discussion

The findings from the early-years practitioners clearly evidence that they link child health and wellbeing with happiness, and they need clarification on what wellbeing is with a clear statement or definition. Both managers and practitioners echo the need for training and a reform in the content of qualifications to equip them with the skills they desire to support early-years children. There is a lack of leadership and consistency in the management of wellbeing in different early-years settings. Managers voiced that they felt unsupported and ill-equipped to support the staff and children in tackling the increase in working to child health and wellbeing. Clear mandatory guidance and training should be available for all early-years practitioners. Finally, the challenge of measuring child health and wellbeing and what tool is more effective has been clearly evidenced; practitioners do not favour one tool over others and do not feel confident in using them. It could be suggested that the tools are not fit for purpose according to the response from the study, and a new model is needed to meet the needs of the practitioners.

4.1. Definition and Understanding of Child Health and Wellbeing

Research has clearly evidenced that a number of emerging themes have been highlighted from the thirty-two early-years practitioners and ten managers; it is clear in both the literature review and the research that there is no clear definition of child health and wellbeing [14,18,19]. This is problematic for practitioners as they struggle to recognise, observe, and monitor in their setting and support is needed by managers to assist the development of this. There is a great need for clarity to generate a clear and comprehensive definition that is concise and understandable for practitioners to use [22]. Furthermore, the research data evidenced that half of the participants involved in the survey have a level-three early-years qualification, with a further quarter having a level-four qualification and a further quarter having a level-five qualification as their highest form of qualification.

It was clear that early-years practitioners had different views in relation to what health and wellbeing is, with many of the less-qualified staff simply referring to it as happiness and whether the child appears to be happy. They further stated that child wellbeing is centred on whether the child feels content and happy. The focus on self-actualization is further relevant to elements of the international PERMA model [9], supporting the notion of achieving happiness. Evidence from the literature indicated that research of Seligman [9] and publications from UNICEF [11]), state that wellbeing is an approach that places happiness and satisfaction, regardless of their socio-economic environment, at the centre of holistic development. This echoes the work of the OECD study of five-year-old children [26], which affirms that in order for a child to feel happy and thrive, they must be reinforced by a strong, solid foundation around them. However, Sointu (2005) disputes these views, believing that wellbeing is simply a ‘notion’ in society and a concept that impacts a person’s happiness.

In comparison, more qualified staff viewed wellbeing as emotional development and the child’s ability to control their emotions. Several responses highlighted that health and wellbeing is all about a child’s emotional state, not just their cognition. This reflects the views of Seaman and Giles [6], who accept that emotional well-being plays an essential role in the relationships that early-years children form, and this supports them to interact with others. The focus group discussions also presented that they regarded health and wellbeing as an emotional developmental stage and believe positive wellbeing can lead to confidence and resilience within the child’s learning.

Managers placed more emphasis on the external factors that can impact the child’s wellbeing, highlighting that if the child’s early atmosphere is toxic, this can impact on their early brain development, which can have detrimental effects for the rest of the child’s life. Similar principles are present in Bronfenbrenner’s [34] ecological framework, which stresses that the influences of social and economic factors form the layers of the community that influence a child’s wellbeing. Furthermore, the multi-layer process of Anspaugh, Hamrick, and Rosato [35] supports the holistic dimensions of wellnesses and the recognition of social, emotional, physical, and spiritual factors. All three ideologies endorse the need for positive interactions in early years and value the significance of this in all areas of child development. Both early-years practitioners and nursery managers value the need of adopting a holistic stance when working with health and wellbeing, stressing the importance of strong leadership within early-years provision, with clear guidance for practitioners in management roles [10]. The data evidenced that their understanding recognised the link between wellbeing and emotional and social development. This underlines that it is the quality of the child’s mental and physical health that supports the overall health of the developing child and supports the overall principles that are presented in the SHANARRI wellbeing model [8], which places the child at the centre, ensuring that overall development and emotions are supported to reach their full potential. Equally, the PERMA model of wellbeing [9] focuses on the holistic elements of development; this multidimensional approach places the emphasis on positive psychology and achievement. Anspaugh, Hamrick, and Rosato [35] further evidence the views that the ‘holistic dimensions of wellnesses’ promote the concept that wellbeing is a multi-layer process that includes all areas of development—social, emotional, physical, and spiritual—thus supporting the child’s holistic development.

Finally, there is evidence presented in the findings that illustrates that many early-years practitioners recognise issues with the child’s health and wellbeing with physical signs that they can observe. Many highlighted the child’s behaviour or recognising a dramatic change in behaviour and sometimes a change in the child’s normal mood. Some highlighted that the child may become more introverted or lack social and communication skills and show little engagement. It was encouraging to see that all staff had some understanding of child health and wellbeing; however, there was a stark difference in their understanding of what health and wellbeing is, with different areas of focus being a priority. Some dictated that health and wellbeing were about happiness and achieving, while others viewed it as a stage of cognitive development that must be nurtured in order for to prosper and be able to build resilience. However, there was a multitude of examples trying to define wellbeing, which replicate the views from the literature review clearly evidencing people’s different views of a definition of wellbeing [14,18].

4.2. The Challenge of Measuring Child Health and Wellbeing and What Model Is More Effective

The study has provided clear findings that both the early-years practitioners and managers lack self-assurance in their ability to use the various wellbeing tools accessed in early-years practice. Nursery staff will look for leadership from their more senior leaders; however, these individuals lack confidence in their own abilities and feel they have a lack of training to support child health and wellbeing. The main findings from the survey illustrated that nursery staff and managers do not feel confident using the adopted tools and felt that they had not received sufficient training to complete the scales. They lacked confidence in their own ability, with some of the less experienced members of the team feeling that they had not had enough experience to recognise and identify what good wellbeing looks like. The views of Coles et al [19] highlight the challenge of early-years intervention in relation to child health and wellbeing and explore the challenge of making improvements to the sector to assist early-years children. Similar views are suggested by Susman-Stillman, Meuwissen, and Watson [36] who recognise the pressures within the early-years sector for practitioners in supporting child health and wellbeing. They also highlighted the high rates of staff turnover and the day-to-day stresses encountered by early-childhood professionals when supporting well-being. They value the need for supervision to be used as a tool by leaders to enable them to develop and strengthen their skills to support wellbeing within nursery settings. These points highlight the necessity of reflective supervisions for staff, which supports the work of Robson, Brogaard-Clausen, and Hargreaves [37], who advocate that this will assist and reinforce early-years practitioners’ confidence in supporting child health and wellbeing. Early-years practitioners need a wide variety of skills to understand children’s feelings, and as key workers, they should work to ensure that they are nurturing children to develop positive relationships and empathy towards others [38,39].

Furthermore, the findings clearly evidence the challenges of working in a deficient area, with both practitioners and managers stating the pressures this causes them as they sometimes have their own mental health issues, having grown up in the local community. One manager emphasised the number of safeguarding concerns she has to address working with poverty. The challenge of practitioners measuring child health and wellbeing is clearly illustrated in the findings, which highlights that no wellbeing tool is used more predominately. The evidence suggests that both the managers and early-years practitioners do not feel confident using them, with eight managers voicing that they have never had training or guidance on how to identify, measure, and support wellbeing.

The principles recognised by the UK government [5] support the need to assist early-years practitioners by adopting a robust system for measuring child wellbeing and raise their self-assurance. Furthermore, the power of early intervention in identifying the early signs of child health and wellbeing, thus nurturing positive experiences and holistic child development, has been identified [38]. Early-years practitioners did not favour any of the health and wellbeing tools, and none have been adopted as mandatory practice. Both the Leuvan scale [9] and SHANARRI wheel [8] have been used to measure and monitor wellbeing. However, the fact that nearly a quarter of the early-years-practitioner respondents highlighted that their setting did not use any formal process for monitoring health and wellbeing was alarming; this could suggest that some practitioners do not appreciate the urgency and relevance of supporting health and wellbeing and the detrimental effect it can have on a child’s development and later life.

With a further twenty-eight percent of the study stating that they use some form of feelings, reward, or progress chart to monitor wellbeing, this equates to nearly half of the participants involved in the research of early-years settings stating that they have no official practice adopted in their setting to monitor and measure child health and wellbeing. Evidence on the findings further highlights that some less-experienced staff struggle to measure and recognise what good wellbeing looks like. This recognises the interpretations specified by the global OECD Child Well-Being Data Portal [26], which ranks England as one of the lowest-ranking global countries when supporting positive early-years involvements for children. Furthermore, the Department for Education [10] International Early Learning and Child Well-being Study (IELS) presents comparisons and highlights the ongoing study analysing the factors that implicate child development. The priorities highlighted emphasise the benefits of observing a holistic experience for early-years children to support their overall development.

The SHANARRI wheel [8] offers a holistic tool to access child health and wellbeing and is set out clearly and guides early-years practice to access a child’s overall development. The visual wheel enables practitioners or less-experienced staff to assess the eight indicators of the wheel and directs them to evaluate these core areas of child development. This would assist the early-years staff who voiced that they have some anxieties in filling in the tool correctly as they were not clear what they were looking for. Furthermore, the PERMA model [9] promotes the purpose of a multidimensional tool being applied in measuring emotions, relationships, and the achievement of wellbeing and happiness, supporting the practitioner to access child wellbeing simultaneously alongside the current EYFS curriculum; the recent Early Learning Goals help form the assessment of the child’s ability to self-regulate, managing by their self and building relationships before progressing into full-time education [5]. Nursery managers also stressed the importance of adopting a tool to measure wellbeing that would complement the Early Learning Goals, so they could see relevance and purpose.

4.3. Qualification and Training Needed to Support Early-Years Children

The study highlighted that over half of the early-years practitioners do not feel qualified and felt that more bespoke training is needed. Practitioners stated that they lack knowledge and simply do not know what they are looking for when identifying the signs and symptoms of child health and wellbeing. They highlight the responsibility of monitoring wellbeing and specified that they often felt out of their depth. The managers echo the same views as they further recognise that less-experienced staff struggled to recognise and monitor their abilities when supporting child health and wellbeing. The findings evidenced that better mandatory training should be available to all staff that is tailor-made for early-years professionals. Qualifications should acknowledge the requisite and further focus is needed to support practitioners in scaffolding child health and wellbeing in the early years. This supports the findings of UK governments [40] that identify the importance of all nursery workers being suitably skilled and well-qualified practitioners in every early-years setting, dictating that a high quality of early education can be a significant predictor of good child development and learning. Recognition within the review focused on children living in low-income areas and highlighted the impact on their wellbeing and the need for better outcomes for these at-risk families [41]. In more current research, Archer and Merrick [22] further recognised the importance of a high-quality workforce in recognising the issues with the child’s emotional wellbeing at the earliest point in order to improve a child’s long-term outcomes and increase the chance of better societal progression. Strong leadership figures are essential to guide and support early-years practitioners in recognising the power of early intervention within settings in order to offer effective strategies and services to support individual needs [6]. Similar views are presented by Coles, Cheyne, and Daniel [19], who state that early-years professionals need clarity on child health and wellbeing and a directed framework that monitors and measures wellbeing.

Early-years leaders dictated that they witness less-experienced staff struggling to recognise wellbeing and are not assertive in monitoring and supporting it. The contemporary research paper of Kay, Wood, Nuttall, and Henderson [42] examines the early-years workforce reform in England and scrutinises early childhood education in relation to policies and qualification. The study presents that current qualifications do not fully provide practitioners with the experience necessary to deliver a high standard of childcare. Furthermore, the level of the qualification does not support newly qualified professionals and limits their experience of supporting emotional child development. However, Wild, Silber Feld, and Nightingale [43] disagree that the standard of better quality within early years is achieved by supporting strong leadership with the sector to shape the reform of early-years practice.

The evidence suggests that both the early-years practitioners and managers see the value of training in relation to supporting health and wellbeing, with the majority of practitioners’ responses; in particular, more qualified early-years staff valued the importance of building relationships and getting to know the children, and view this as an important element of supporting child health and wellbeing. This reflects the views of Danby & Hamilton [18], who believes that relationships in the early years play a fundamental part of communication and development, supporting the practitioner to build a rapport with their key children. The importance of successful relationships is focused on within the PERMA model of wellbeing [9], which is the focus of one of the five priorities for happiness and positive wellbeing. As key workers, practitioners need to develop their skill to comprehend children’s emotions and guarantee they are building positive relationships [36]. It has been suggested that early-years practitioners view wellbeing differently, and the findings have illustrated that there is a need for a clear definition of wellbeing to be established as there is confusion among the early-years sector and a need for clarity for professionals [17,18].

The research further illustrated that additional training is needed to support the early-years workforce and combat the rising issues of supporting low child-health and wellbeing [22,42]. These issues further place the attention on current early-years qualifications that shape and develop the early-years workforce to influence the reform of course content and reflect the current rise and issues in health and wellbeing concerns. Furthermore, the importance of the key worker relationship and the need for practitioners to effectively build rapport with children is emphasised [40,44]. The research concurs by focusing on the power of leadership within the early-years sector and the need to shape and develop further early-years practice, qualifications, and training.

5. Conclusions

On reflection, it is apparent that early-years practice has changed immensely over the last twenty-five years, and the challenges that practitioners face in the sector is demanding. The words of one early-years practitioner resonate in my mind: “I do not know what I am looking for, what does good child health and wellbeing look like?”. Recognition must be given to the practitioners working in the daily challenges to support the children in a deprived socio-economic community [22,34]. As early-years educators and leaders, it is our role to ensure we shape and train practitioners to meet the needs of current contemporary practice and arm them with the skills to support their roles. The evidence clearly indicated that improvements need to be made with qualifications within early years, so practitioners need to study child health and wellbeing in more depth and recognise the need to measure the impact and the contributing factors that impact on child development and comprehend the signs and symptoms of low wellbeing and how they can be identified. Nursery managers should be given the power to adopt a wellbeing measuring tool they feel confident using, where they can train the nursery workers in their setting, so a holistic approach is embraced. It is clear how practice has changed over the years with government data highlighting the magnitude of child health and wellbeing concerns; therefore, there is a need for qualification reform to reflect the changing issues within the sector [22,45]. The subject of child health and wellbeing was never discussed years ago, but through education and the constant pressure of society, the evolving issues of health and wellbeing need to be supported efficiently. An inclusive approach is needed within the early-years curriculum, and fundamental changes need to empower early-years leaders so that they support practitioners to gain confidence and skills. The cohesion between the findings clearly advocates the need for a mandatory tool to be adopted by nursery leaders and practitioners, alongside comprehensive training which will arm early-years practitioners with the tools to support children living in the deprived area of Blackpool. The introduction of an effective holistic measuring tool will support leadership in early-years care, giving practitioners the confidence to recognise the signs from five key areas that impact early child development.

SERCCH principles:

- Socio-economic factors

- Emotional intelligence

- Relationships

- Communication

- Contentment

- Happiness

My wellbeing model will reaffirm the principles highlighted from the EYFS [5] and will centre around the holistic development of health and wellbeing, concentrating on happiness and contentment, emotional intelligence, communication and relationships, and external socio-economic influences [6,22,29]. The tool will allow practitioners to make an initial assessment of the child in relation to the external socio-economic factors that can influence child health and wellbeing. The model will further support the key principles identified within the EYFS early-learning goals for personal, social, and emotional development, which highlight self-regulation, managing the self, and building relationships (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

SERCCH model of wellbeing.

Guidance sheet for early-years practitioners

| Socio-economic factors | What contributing factors influence the child’s day-to-day life? |

| Emotional intelligence | Can the child regulate their own emotions? Can the child control their behaviour and with no evidence of emotional outbursts? Can the child follow instructions and simple rules? |

| Relationships | Does the child form relationships peer to peer and with other adults? Can the child be comforted by a key worker or an adult? Does the child show empathy towards others? |

| Communication | Does the child play with other children? Does the child speak with others? |

| Contentment | Is the child content and happy? Does the child show confidence with attempt new challenges? Does the child cope with failure and adversity and show resilience to the situation? |

| Happiness | Does the child become upset easily and show emotional maturity? Does the child laugh and engage positively with others? |

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of University of Aberdeen 15 September 2020.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available because they are presented together with other data that will be the subject of future research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Joint Strategic Needs Assessment Blackpool 2020. Available online: https://www.blackpooljsna.org.uk/Blackpool-Profile/Population.aspx (accessed on 14 August 2020).

- Public Health England Blackpool Child Health Profile. England. 2020. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/2019-child-health-profiles (accessed on 14 December 2020).

- National Children Bureau Publication Great Expectations. Raising Aspirations for Our Children; NCB: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- The National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC). Children Living in Families Facing Adversity; NSPCC: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Education. Statutory Framework for the Early Years Foundation Stage. 2021. Available online: https://www.foundationyears.org.uk/eyfs-statutory-framework/ (accessed on 16 March 2021).

- Seaman, H.; Giles, P. Supporting children’s social and emotional well-being in the early years: An exploration of practitioners’ perceptions. Early Child Dev. Care 2021, 191, 861–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacRae, C.; Jones, L. A philosophical reflection on the “Leuven Scale” and young children’s expressions of involvement. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scottish Government. Getting It Right for Every Child (GIRFEC). 2006. Available online: https://www.gov.scot/policies/girfec/principles-and-values/ (accessed on 12 September 2020).

- Seligman, M. Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being; Free Press: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Education. International Early Learning and Child Well-Being Study (IELS); HMSO: London, UK, 2018.

- UNICEF. A Child’s Guide to the Child Well-Being Report; UNICEF: Paris, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. UN Convention on the Rights of the Child Bill United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UCNRC) 2019. Available online: https://www.unicef.org.uk/what-we-do/un-convention-child-rights/ (accessed on 16 November 2020).

- The Children Society. What Is Child Well-Being? 2020. Available online: https://www.childrenssociety.org.uk/what-is-child-wellbeing (accessed on 19 February 2020).

- Dodge, R.; Daly, A.; Huyton, J.; Sanders, L. The challenge of defining well-being. Int. J. Wellbeing 2015, 2, 222–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sointu, E. The rise of an ideal: Tracing changing discourses of wellbeing. Sociol. Rev. 2005, 53, 255–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, V.; Mayall, B. What is wrong with children’s well-being in the UK? Questions of meaning and measurement. J. Soc. Welf. Fam. Law 2009, 31, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.; Aked, A. A Guide to Measuring Children’s Well-Being; Action for Children & the New Economics Foundation: London, UK, 2009; p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Danby, G.; Hamilton, P. Addressing the ‘elephant in the room’. The role of the primary school practitioner in supporting children’s mental well-being. Pastor. Care Educ. 2016, 34, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, E.; Cheyne, H.; Daniel, E. Early year’s interventions to improve child health and wellbeing: What works, for whom and in what circumstances? Protocol for a realist review. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selwyn, J.; Riley, S. Measuring well-being: A literature review. In Hadley Centre for Adoption and Foster Care Studies; University of Bistol: Bistol, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron EMathers, J.; Parry, J. ‘Health and well-being’: Questioning the use of health concepts in public health policy and practice. Crit. Public Health 2006, 16, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, N.; Merrick, B. Quality or Quantity in Early Year’s Policy: Time to Shift the Balance; Sutton Trust: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, L.; Green, S.; Falecki, D. Positive early childhood education: Expanding the reach of positive psychology into early childhood. Eur. J. Appl. Posit. Psychol. 2017, 1, 2397–7116. [Google Scholar]

- Zabeli, N.; Gjelaj, M. Preschool teacher’s awareness, attitudes and challenges towards inclusive early childhood education: A qualitative study. Cogent Educ. 2020, 7, 156–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.L.T.; Lane, S.; Brown, G.; Leung, C.; Kwok, S.W.H.; Chan, S.W.C. Systematic review of the impact of unstructured play interventions to improve young children’s physical, social, and emotional wellbeing. Nurs. Health Sci. 2020, 22, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Early Learning and Child Well-Being: A Study of Five-year-Olds in England, Estonia, and the United States; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- File, N.; Mueller, J.; Wisneski, D.B.; Stremmerl, A.J. Understanding Research in Early Childhood Education: Quantitative and Qualitative Methods; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rhedding-Jones, J. Who chooses what research methodology? In Early Childhood Qualitative Research; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, L.; Ravenscroft, J. Building Research Design in Education; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Flewitt, R.S.; Ang, L. Research Methods for Early Childhood Education; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gorad, G. Combining Methods in Educational and Social Research; Open University Press: Berkshire, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, C. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual. Res. Psychol. 2020, 18, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, N. Using templates in the thematic analysis of text. In Essential Guide to Qualitative Methods in Organisational Research; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Anspaugh, D.; Hamrick, M.; Rosato, F. Wellness: Concepts and Applications; McGraw Hill: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Susman-Stillman, A.; Meuwissen, A.; Watson, C. Reflective Supervision/Consultation and Early Childhood Professionals’ Well-Being: A Qualitative Analysis of Supervisors’ Perspectives. Early Educ. Dev. 2020, 31, 1151–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, S.; Brogaard-Clausen, S.; Hargreaves, D. Loved or listened to? Parent and practitioner perspectives on young children’s well-being. Early Child Dev. Care 2019, 189, 1147–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, C.; Raver, C. Child development in the context of adversity: Experiential canalization of brain and behaviour. Am. Psychol. 2012, 67, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudry, A.; Wimer, C. Poverty is not just an indicator: The relationship between income, poverty, and child well-being. Acad. Paediatr. 2016, 16, S23–S29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leadsom, A.; Field, F.; Burstow, P.; Lucas, C. The 1001 Critical Days: The Importance of the Conception to Age Two Period: A Cross Party Manifesto. 2013; HMSO: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sylva, K.; Melhuish, E.; Sammons, P.; Siraj, I.; Taggart, B. The Effective Provision of Pre-School Education (EPPE). Project: Findings from the Early Primary Years; DfES Publications: Nottingham, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kay, L.; Wood, E.; Nuttall, J.; Henderson, L. Problematising policies for workforce reform in early childhood education: A rhetorical analysis of England’s Early Years Teacher Status. J. Educ. Policy 2021, 36, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, M.; Silberfeld, C.; Nightingale, B. More? Great? Childcare? A Discourse Analysis of Two Recent Social Policy Documents Relating to the Care and Education of Young Children in England. Int. J. Early Years Educ. 2015, 23, 230–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Baustad, G.; Bjørnestad, E. Everyday interactions between staff and children aged 1–5 in Norwegian ECEC. Int. J. Child Care Educ. Policy 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutbrown, C. Foundations for Quality: The Independent Review of Early Education and Childcare Qualifications: Final Report. 2014. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/nutbrown-review-foundations-for-quality (accessed on 16 January 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).