Preservice Teacher Perceptions of the Online Teaching and Learning Environment during COVID-19 Lockdown in the UAE

Abstract

1. Introduction

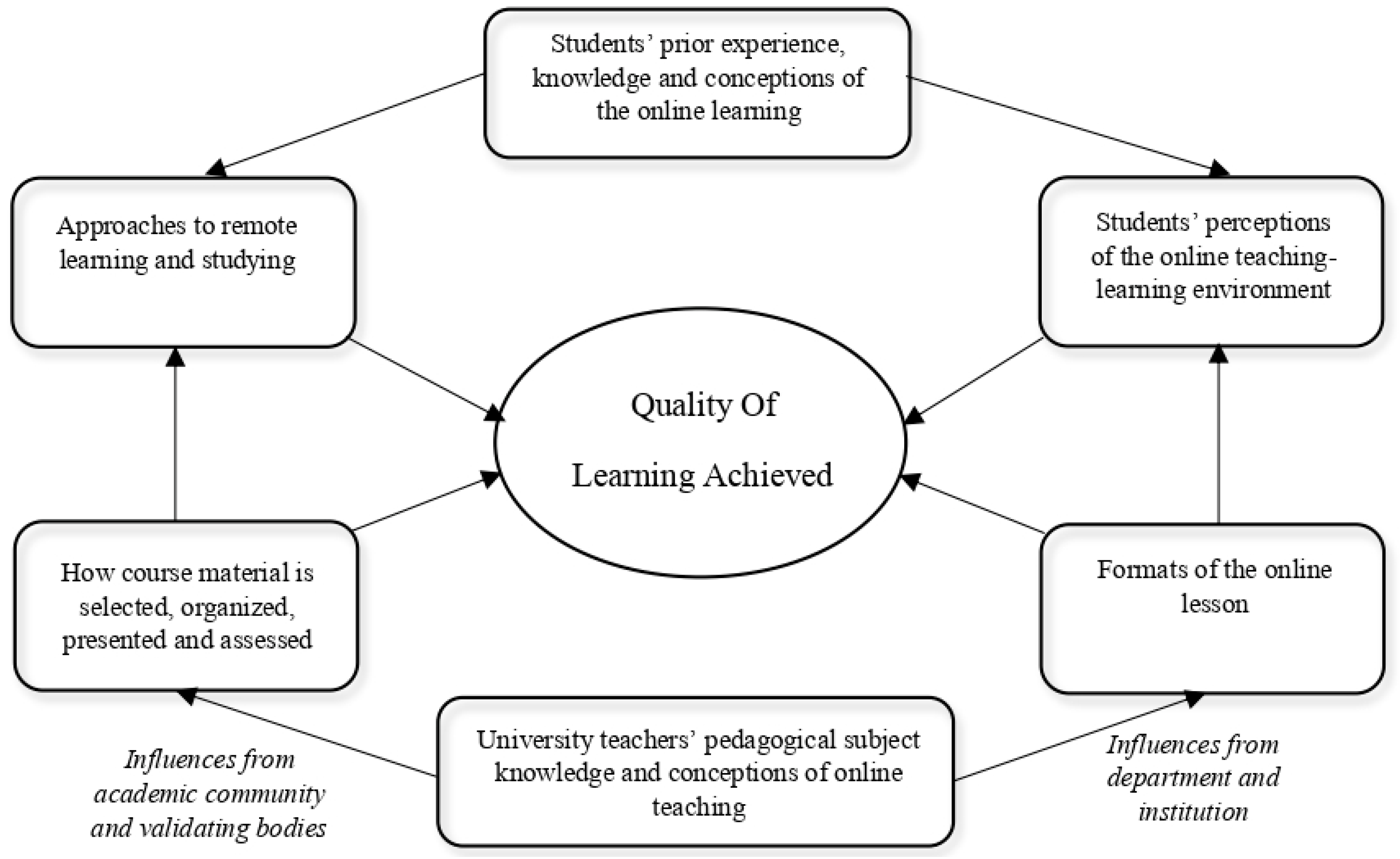

1.1. Promoting High Quality E-Learning

1.2. Student Perceptions and Approaches to Learning

1.3. Student-Teacher Technology Adoption

1.4. The Importance of Community and Belongingness

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Context

2.2. Methodology

2.2.1. Participant Sampling

2.2.2. Study Procedure

2.2.3. Questionnaires

2.2.4. Lesson Delivery

- The online version of what is known as the ‘traditional lecture’ [33] where lesson knowledge is imparted didactically with the assistance of a PowerPoint presentation.

- The ‘flipped lecture’, where learning concepts are recorded in 20 min video concept chunks [34]. They are uploaded to the learning platform and followed up with a seminar discussion session. ‘Task-driven interaction’ [35] was the basis of the seminars. These were either through group interaction or one-to-one tutorial discussions.

- ‘Online presentations’, where, as an alternative to in-person presentations, students were required to present online to peers. This was either formatively, presenting ideas for written assignments, or as part of their summative assessments.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Past Experiences of Online Teaching and Learning Questionnaire

2.3.2. Current Experiences of Online Teaching and Learning Questionnaire

- Lesson Organisation (‘It was clear to me what I was supposed to learn in these lessons’; seven items),

- Student Independence (‘This unit encouraged me to related what I learned to issues in the wider world’; four items),

- Lesson Delivery (‘Teachers helped us to see how you are supposed to think and reach conclusions’; five items),

- Community and Belongingness (‘Talking with other students helped me to develop my understanding’; four items),

- Overall Enjoyment (‘I enjoyed being involved in this period of online learning’; three items).

2.3.3. Focus Group

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. RQ1 Past Experiences with Online Learning

3.1.1. RQ1 A Past Learning Approaches

The traditional way for me was like, I could make notes when we were having our lessons. When I’m doing my assignments, I always go back to my notes and see if I have any doubts or something.(Participant 28)

When we have face-to-face lectures in uni, there’s a sense of routine and discipline that we can follow.(Participant 23)

3.1.2. RQ1 B Expectations for E-Learning

I know for myself in the beginning when I was looking at studying I did look at distance learning because I work full time. It’s nice to know that this could be something in the future that could be implemented.(Participant 7)

It’s really nice to have everyone together regardless of whether we are in one room or not… Virtually being able to talk to each other backward and forward it really makes it easier.(Participant 25)

It’s easy for people to lose their focus when it comes to presentations online. But, if you build your skills in <online> presenting, you’re going to be able to render people’s interest in your topic.(Participant 14)

I feel like when we come to class, we’re all together, we get to share our struggles and our stress. It’s very different to 10 min chats online and then online messages.(Participant 19)

3.2. RQ2 Current Experiences and Influences on these Experiences

3.2.1. RQ2 A Efficacy of E-Learning, Skills Gained and Challenges Faced

It is really surprising that this has actually worked out…The fact that this has worked out very smoothly and has gone really well, I’m really happy about that.(Participant 7)

I personally feel I enjoy the live…classes I feel like when it comes to listening to a recording, I don’t personally go with that I don’t understand that really very well.(Participant 29)

It’s so mentally draining, we’re, so we’re stressed, but not enough to be motivated to do our work just because there’s no structure there is no routine…You lose the discipline and routine if you’re doing online. It’s not the same feel as being in the classroom.(Participant 19)

I found it really difficult to follow the presentation that other colleagues were giving. And when I was giving it myself, I just felt like I felt like I was talking to myself.(Participant 29)

The recorded and the live sessions are really good but I don’t think it [online learning] is a method we prefer, because, obviously, we’ve been taught for so long, in the traditional face to face.(Participant 19)

3.2.2. RQ2 B Changes in Learning Approach and Influences on Learning

For me <Goto Meeting> is an easy app to use. In this time of uncertainty, it’s better to have any sort of a way where we can converse and clear our doubts and arrange for resources or anything that we need, so I think it’s kind of a very helpful tool.(Participant 23)

Using a live Google document was good because the others were able to comment and share their perspectives on your presentation. I liked the Google document and tutorials, because it still gets the same sense and same feeling as seeing you in class.(Participant 22)

3.2.3. RQ2 C Influence of Changes in Pedagogy and Lesson Delivery

I think that the live lectures are good, because it’s a way for us to still interact and to be able to hear and listen to everyone else’s perspectives of things, although it’s not like a classroom, it still gives a vibe of the classroom.(Participant 13)

I also like the live lecture and presentations on Goto Meeting, because, if I’m being honest, it’s the closest thing we have to being back into the classroom, and we’re even allowed to still ask questions via the chat.(Participant 14)

For me the live content is really beneficial because I am right there with you, any doubts I can ask and clear right away.(Participant 22)

We can interrupt the slideshows and ask questions as they go along.(Participant 7)

Maybe we will start to like it, but because it is the beginning is why we’re still saying that we prefer face-to-face, and it’s something new to us, that’s why we want to go back to the old style of seeing you one-to-one.(Participant 22)

4. Discussion of Findings

4.1. Efficacy of E-Learning

4.2. The Influence of Prior Experiences and Expectations

4.3. Pedagogical Impact

4.4. Technology Adoption, Barriers and Challenges

4.5. Communities of Learning and Belongingness

4.6. Limitations

4.7. Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gulf News. All UAE Schools, Colleges to Close for 4 Weeks from Sunday as Coronavirus Precautionary Measure. 3 March 2020. Available online: https://gulfnews.com/uae/all-uae-schools-colleges-to-close-for-4-weeks-from-sunday-as-coronavirus-precautionary-measure-1.1583260164593 (accessed on 21 October 2022).

- National Agenda. First-Rate Education System. From UAE Vision 2021. 2018. Available online: https://www.vision2021.ae/en/national-agenda2021/list/frst-rate-circle (accessed on 8 March 2022).

- Turvey, K. Pedagogical-research designs to capture the symbiotic nature of professional knowledge and learning about e-learning in initial teacher education in the UK. Comput. Educ. 2010, 54, 783–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatnall, A.; Fluck, A. Twenty-five years of the Education and the Information Technologies journal: Past and future. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 1359–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hounsell, D.; Entwistle, N.; Anderson, C.; Bromage, A.; Day, K.; Land, R.; Litjens, J.; McCune, V.; Meyer, E.; Reimann, N.; et al. ELT Project—The Team. 2001. Available online: https://www.etl.tla.ed.ac.uk/biogs.html (accessed on 21 October 2022).

- Entwistle, N.; McCune, V.; Hounsell, J. Occasional Report 1: Approaches to Studying and Perceptions of University Teaching-Learning Environments: Concepts, Measures and Preliminary Findings; The University of Edinburgh: Edinburgh, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entwistle, N.; Ramsden, P. Understanding Student Learning; Croom Helm: Kent, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Hounsell, D.; Hounsell, J. Teaching-learning environments in contemporary mass higher education. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. Monogr. Ser. II 2007, 4, 91–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreber, C. Higher Education Research & Development the Relationship between Students’ Course Perception and their Approaches to Studying in Undergraduate Science Courses: A Canadian experience The Relationship between Students’ Course Perception and their Approaches. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2003, 22, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizzio, A.L.F.; Wilson, K.; Simons, R. University students’ perceptions of the learning environment and academic outcomes: Implications for theory and practice. Stud. High. Educ. 2002, 27, 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parpala, A.; Lindblom-Ylänne, S.; Komulainen, E.; Entwistle, N. Assessing students’ experiences of teaching-learning environments and approaches to learning: Validation of a questionnaire in different countries and varying contexts. Learn. Environ. Res. 2013, 16, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J.T.; Price, L. Approaches to studying and perceptions of academic quality in electronically delivered courses. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2003, 34, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J.T.E. Students’ perceptions of academic quality and approaches to studying in distance education. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2005, 31, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, C.; Flores, M.A. COVID-19 and teacher education: A literature review of online teaching and learning practices. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2020, 43, 466–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoumi, D. Situating ICT in early childhood teacher education. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2020, 26, 3009–3026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, C.; Moore, S.; Lockee, B.; Trust, T.; Bond, A. The Difference between Emergency Remote Teaching and Online Learning. Educause 2020, 1–12. Available online: https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-difference-between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-online-learning (accessed on 21 October 2022).

- Davis, F.D.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Warshaw, P.R. User Acceptance of Computer Technology: A Comparison of Two Theoretical Models. Manag. Sci. 1989, 35, 982–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, M.; Xu, Y.; Yuecheng, Y. An Enhanced Technology Acceptance Model for Web-Based Learning. J. Inf. Syst. Educ. 2004, 15, 365. [Google Scholar]

- Punnoose, A.C. Determinants of intention to use eLearning based on the technology acceptance model. J. Inf. Technol. Educ. Res. 2012, 11, 301–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.K.; Lin, P.C.; Chen, A.N. An empirical study of behavioral intention model: Using learning and teaching styles as individual differences. J. Discret. Math. Sci. Cryptogr. 2017, 20, 19–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, D.C. Social Determinants of Information Systems Use. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 1989, 5, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossberger, K.; Tolbert, C.J.; Stansbury, M. Virtual Inequality: Beyond the Digital Divide; Georgetown University Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sotardi, V.A. On institutional belongingness and academic performance: Mediating effects of social self-efficacy and metacognitive strategies. Stud. High. Educ. 2022, 47, 2444–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitlock, B.; Ebrahimi, N. Beyond the library: Using multiple, mixed measures simultaneously in a college-wide assessment of information literacy. Coll. Res. Libr. 2016, 77, 236–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gregori, P.; Martínez, V.; Moyano-Fernández, J.J. Basic actions to reduce dropout rates in distance learning. Eval. Program Plan. 2018, 66, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, A.B.; Karataş, S. Why do open and distance education students drop out? Views from various stakeholders. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2022, 19, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, N.; Zhang, M.; Qi, D. Effects of different interactions on students’ sense of community in e-learning environment. Comput. Educ. 2017, 115, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpershoek, H.; Canrinus, E.T.; Fokkens-Bruinsma, M.; de Boer, H. The relationships between school and students’ motivational, social-emotional, behavioural, and academic outcomes in secondary education: A meta-analytic review. Res. Pap. Educ. 2020, 35, 641–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S.A.; Ashiq, M.; Rehman, S.U.; Rashid, S.; Tayyab, N. Students’ Perceptions and Experiences of Online Education in Pakistani Universities and Higher Education Institutes during COVID-19. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corry, M.; Chih-Hsuing, T. eLearning_Communities. Q. Rev. Distance Educ. 2002, 3, 207–218. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, L.; Manion, L.; Morrison, K.R.B. Research Methods in Education, 8th ed.; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- British Educational Research Association. Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research; British Educational Research Association: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Akçayır, G.; Akçayır, M. The flipped classroom: A review of its advantages and challenges. Comput. Educ. 2018, 126, 334–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, D.M.; Kaya, T. How Flipping your first-year digital circuits course positively affects student perceptions and learning. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2015, 31, 1126–1138. [Google Scholar]

- Hare, A.P.; Davies, M.F. Social interaction. In Small Group Research: A Handbook; Hare, A.P., Blumberg, H.H., Davies, M.F., Kent, M.V., Eds.; Ablex: Norwood, NJ, USA, 1994; pp. 169–193. [Google Scholar]

- Karagiannopoulou, E.; Milienos, F.S. Testing two path models to explore relationships between students’ experiences of the teaching–learning environment, approaches to learning and academic achievement. Educ. Psychol. 2015, 35, 26–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogashana, D.; Case, J.M.; Marshall, D. What do student learning inventories really measure? A critical analysis of students’ responses to the Approaches to Learning and Studying Inventory. Stud. High. Educ. 2012, 37, 783–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marton, F.; Säljö, R. Approaches to learning. In The Experience of Learning; Marton, F., Hounsell, D., Entwistle, N., Eds.; Scottish Academic Press: Edinburgh, UK, 1984; pp. 36–55. [Google Scholar]

- Tuttas, C.A. Lessons learned using web conference technology for online focus group interviews. Qual. Health Res. 2015, 25, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charbonneau-Gowdy, P. Beyond Stalemate: Seeking Solutions to Challenges in Online and Blended Learning Programs. Electron. J. E-Learn. 2018, 16, 56–66. [Google Scholar]

- Czerkawski, B.C.; Lyman, E.W. An Instructional Design Framework for Fostering Student Engagement in Online Learning Environments. TechTrends 2016, 60, 532–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, N.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M. Interactive Learning Environments Retaining learners by establishing harmonious relationships in e-learning environment Retaining learners by establishing harmonious relationships in e-learning environment. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2019, 27, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oncu, S.; Cakir, H. Research in online learning environments: Priorities and methodologies. Comput. Educ. 2011, 57, 1098–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Ardura, I.; Meseguer-Artola, A. What leads people to keep on e-learning? An empirical analysis of users’ experiences and their effects on continuance intention. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2016, 24, 1030–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, N.S. Is FLIP enough? or should we use the FLIPPED model instead? Comput. Educ. 2014, 79, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Scavarda, A.J.; Waxin, M.F. Key issues and challenges in e-government development: An integrative case study of the number one eCity in the Arab world. Inf. Technol. People 2012, 25, 395–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsell, M.; Ambler, T.; Jacenyik-Trawoger, C. Ethics in higher education research, Studies in Higher Education. Stud. High. Educ. 2014, 39, 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denscombe, M. The Good Research Guide: For Small-Scale Social Research Projects, 6th ed.; Open University Press, McGraw-Hill Education: Berkshire, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cristina Bettez, S. Navigating the complexity of qualitative research in postmodern contexts: Assemblage, critical reflexivity, and communion as guides. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 2015, 28, 932–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Past Surface Approach | Past Strategic Approach | Past Deep Approach | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 3.42 | 2.04 | 1.79 |

| Standard Deviation | 0.71 | 0.48 | 0.41 |

| Skewness | −0.71 | 0.44 | 0.21 |

| Standard Error Of Skewness | 0.46 | 0.46 | 0.46 |

| Kurtosis | 0.82 | 0.71 | −0.96 |

| Standard Error of Kurtosis | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.89 |

| Self & Social Development | Interest & Engagement | Career & Academic | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 1.69 | 2.03 | 1.61 |

| Standard Deviation | 0.53 | 0.41 | 0.51 |

| Skewness | −0.59 | 0.7 | 0.91 |

| Standard Error of Skewness | 0.46 | 0.46 | 0.46 |

| Kurtosis | −0.06 | 0.29 | 0.76 |

| Standard Error of Kurtosis | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.89 |

| Lesson Organisation | Student Independence | Lesson Delivery | Community & Belongingness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 1.37 | 1.63 | 1.5 | 1.41 |

| Standard Deviation | 0.4 | 0.61 | 0.43 | 0.56 |

| Skewness | 1.1 | 1.1 | 0.88 | 1.79 |

| Standard Error of Skewness | 0.43 | 0.43 | 0.43 | 0.43 |

| Kurtosis | 0.35 | 2.9 | 0.4 | 3.2 |

| Standard Error of Kurtosis | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.85 |

| Mean | Standard Deviation | |

|---|---|---|

| What I was expected to know about Online Learning to begin with | 2.1 | 1.29 |

| The ideas and problems I had to deal with | 2 | 1.22 |

| The skills or technical skills I needed | 1.83 | 0.89 |

| Working with other students | 2.55 | 1.12 |

| Organising and being responsible for my own learning | 1.76 | 0.95 |

| Communicating knowledge and ideas effectively | 2.24 | 1.02 |

| Tracking down information for myself | 2.55 | 1.24 |

| Information technology/computing skills | 2.45 | 0.99 |

| Mean | Standard Deviation | |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge and understanding about the topics covered | 2.31 | 1.07 |

| Ability to think about ideas or to solve problems | 1.79 | 0.94 |

| Ability to work with other students | 2.21 | 0.86 |

| Organising and being responsible for my own learning | 2.21 | 0.98 |

| Ability to communicate knowledge and ideas effectively | 2.28 | 1.16 |

| Ability to track down information | 2.59 | 1.21 |

| Information technology/computing skills | 2.1 | 0.77 |

| Current Surface | Current Strategic | Current Deep | Past Surface | Past Strategic | Past Deep | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current Surface | Pearson Correlation | 1 | −0.66 | 0.15 | 0.53 ** | −0.11 | −0.11 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.73 | 0.44 | 0.01 | 0.58 | 0.6 | ||

| Current Strategic | Pearson Correlation | −0.66 | 1 | 0.45 * | −0.34 | 0.56 ** | 0.31 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.73 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.13 | ||

| Current Deep | Pearson Correlation | 0.15 | 0.45 * | 1 | 0.14 | 0.36 | 0.44 * |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.44 | 0.02 | 0.5 | 0.08 | 0.03 | ||

| Past Surface | Pearson Correlation | 0.53 ** | −0.34 | 0.14 | 1 | −0.22 | 0.03 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.5 | 0.28 | 0.87 | ||

| Past Strategic | Pearson Correlation | −0.11 | 0.56 ** | 0.36 | −0.22 | 1 | 0.54 ** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.58 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.28 | 0.01 | ||

| Past Deep | Pearson Correlation | −0.11 | 0.31 | 0.44 * | 0.03 | 0.54 ** | 1 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.6 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 0.87 | 0.01 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Past | Pearson Correlation | 1 | −0.22 | 0.34 | 0.3 | −0.13 | −0.29 | 0.08 | 0.01 |

| Surface | Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.277 | 0.871 | 0.142 | 0.523 | 0.152 | 0.684 | 0.982 | |

| (2) Past | Pearson Correlation | −0.23 | 1 | 0.55 ** | 0.55 ** | 0.62 ** | 0.6 ** | 0.56 ** | 0.64 ** |

| Strategic | Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.277 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.000 | |

| (3) Past | Pearson Correlation | 0.03 | 0.54 ** | 1 | 0.21 | 0.47 * | 0.13 | 0.28 | 0.26 |

| Deep | Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.871 | 0.004 | 0.296 | 0.015 | 0.532 | 0.168 | 0.174 | |

| (4) Lesson | Pearson Correlation | −0.3 | 0.55 ** | 0.21 | 1 | 0.45 * | 0.75 ** | 0.59 ** | 0.44 * |

| Organisation | Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.142 | 0.004 | 0.296 | 0.014 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.016 | |

| (5) Student | Pearson Correlation | 0.13 | 0.62 ** | 0.47 * | 0.45 * | 1 | 0.6 ** | 0.64 ** | 0.79 ** |

| Independence | Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.523 | 0.001 | 0.015 | 0.014 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| (6) Lesson | Pearson Correlation | −0.29 | 0.6 ** | 0.13 | 0.75 ** | 0.6 ** | 1 | 0.7 ** | 0.59 ** |

| Delivery | Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.152 | 0.001 | 0.532 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.001 | |

| (7) Community & | Pearson Correlation | 0.09 | 0.56 ** | 0.28 | 0.59 ** | 0.64 ** | 0.7 ** | 1 | 0.63 ** |

| Belongingness | Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.684 | 0.003 | 0.168 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| (8) Overall | Pearson Correlation | 0.01 | 0.64 ** | 0.28 | 0.44 * | 0.79 * | 0.59 * | 0.63 * | 1 |

| Enjoyment | Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.982 | 0.000 | 0.174 | 0.016 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Anderson, P.J.; England, D.E.; Barber, L.D. Preservice Teacher Perceptions of the Online Teaching and Learning Environment during COVID-19 Lockdown in the UAE. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 911. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12120911

Anderson PJ, England DE, Barber LD. Preservice Teacher Perceptions of the Online Teaching and Learning Environment during COVID-19 Lockdown in the UAE. Education Sciences. 2022; 12(12):911. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12120911

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnderson, Philip John, Dawn Elizabeth England, and Laura Dee Barber. 2022. "Preservice Teacher Perceptions of the Online Teaching and Learning Environment during COVID-19 Lockdown in the UAE" Education Sciences 12, no. 12: 911. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12120911

APA StyleAnderson, P. J., England, D. E., & Barber, L. D. (2022). Preservice Teacher Perceptions of the Online Teaching and Learning Environment during COVID-19 Lockdown in the UAE. Education Sciences, 12(12), 911. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12120911