Education in Cultural Heritage: A Case Study of Redesigning Atayal Weaving Loom

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Atayal Weaving Culture and Multiple Identities

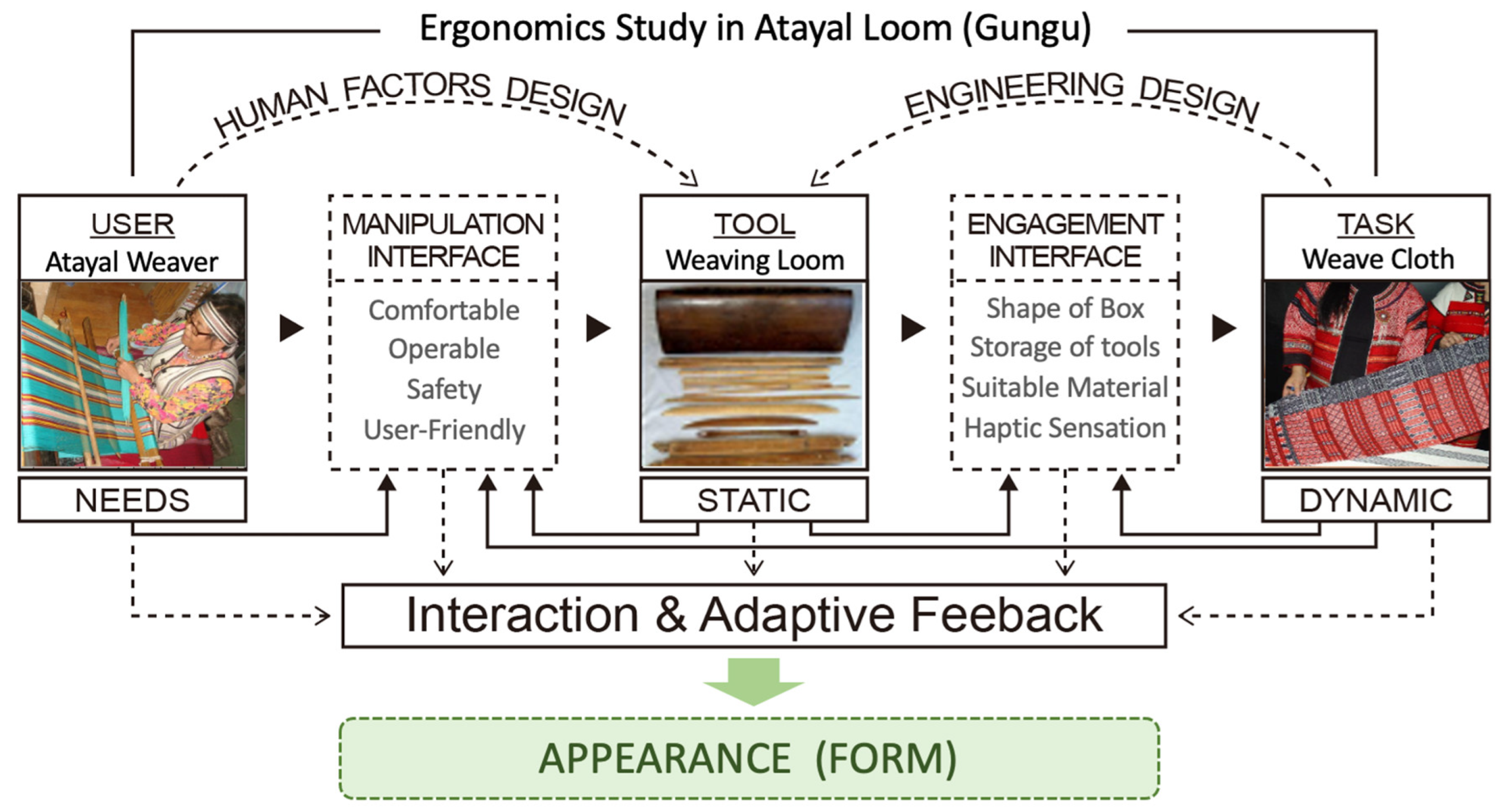

2.2. Cultural Ergonomics in Atayal Loom

2.3. Transformation and Inkle Loom

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. User, Tool, and Task

- User (expert/novice): Yuma Taru is an outstanding weaver and prominent artist from the Atayal tribe in Miaoli County. She is one of the most important spirits who inspired and facilitated this empirical research. With her workfellows, they not only have worked to preserve the Atayal weaving tradition for decades, they have endeavored to extend the Atayal weaving arts to modern audiences. In the past, the Atayal tribe utilized oral transmission without literal writing. Thus, daughters had to learn their weaving knowledge from their mother’s in-person instruction and verbal description, which all relied on excellent memories. Through their efforts, much of the abundant data and special presentations about beautiful aboriginal patterns have been preserved in modern weavers’ notation [17,26,58]. Furthermore, Taru is trying to improve a school for the impoverished village children on the hills above Miaoli, and has established the Lihang workshop as a cultural center to promote Atayal cultural learning and creation [59]. While Taru was teaching the Atayal loom at the Lihang workshop in Miaoli, several children were attracted and wanted to know how to weave. Taru realizes that the classroom situations in rural primary schools need to be greatly improved for effective cultural learning, especially regarding cost, budget, space, and suitable devices. She believes that through such improvement, children and beginners will have a fair opportunity to learn and enjoy a relatively inexpensive and easily-learned introduction to this valuable and enjoyable art and craft. Thus, in this study, kids from the rural primary school are the major participants invited to operate and compare two kinds of new inkle devices.

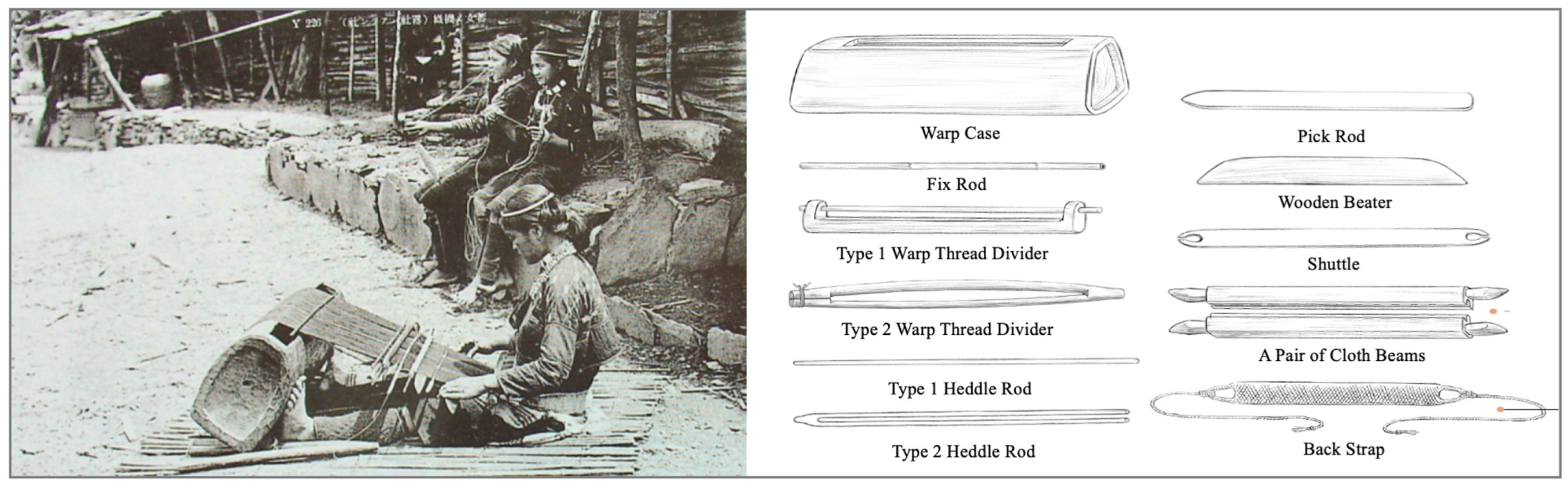

- Tool (object/product): The Atayal traditional weaving box (Figure 1, before), called a weaving loom in the Atayal language, is the subject of this study. In the studies and reviews in Section 2 this study illustrates the relations and interactions in the three cultural levels, as shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3. One of the characteristic appearances of the Atayal traditional loom is its wooden box with storage space, called a warp case. Its primary usability is recognized as a fundamental part of the Atayal horizontal backstrap weaving loom. However, the weaving posture of sitting on the ground usually causes cumulative trauma to the weaver’s back and waist. In brief, the cultural meaning of the weaving loom is its symbolization of multiple identities: gender identity among Atayal females in the past, and the collective ethnic identity of Atayal culture today [18,19,22]. Thus, this research argues that the Atayal loom is a cultural object that could be transformed from a traditional weaving tool into a cultural product.

- Task (weave/experience): In the past, Atayal people had to weave textiles for daily life and specific dress for particular events and ceremonies. In contemporary times, Atayal people have woven for museum displays or tourism markets. In the ancient period, Atayal people wove textiles with tribal patterns. Recently, the Atayal and their fellow tribal people keep trying to retrace their ancestors’ wisdom and revive local communities. Although they are from different generations, most of these weavers are looking forward to accomplishing their life duties or artistic ideals by weaving. In addition to weaving for their livelihood, museums, or markets, other concerns may include seeking alternative ways to pass on their inherited traditions and preserve their culture. Today, the Atayal proudly claim that the weaving culture has been recognized as the collective ethnic identity of the Atayal [18]. As Kreifeldt has mentioned, the artifacts of a culture are its external expression, and our modern products need a connection with a spiritual foundation [60]. Thus, according to the preceding discussions and looking into the future, this study extracts and re-identifies the adaptive meaning of “weaving loom” culture as “weaving for pleasure” conducted with the user experience strategy to meet demands and balance in the new era. This study expects the redesigned modern weaving box to facilitate and propel the improvement in tribal culture learning capably both affordably and sustainably.

3.2. Design Transformation

3.2.1. Sustainable Model of the Cultural Ergonomic Cycle

3.2.2. Transforming the Traditional Atayal Weaving Loom into a Modern Weaving Box

- Identification: This study retrospect and discriminates the significant meaning of the Atayal weaving culture and traditional loom (Figure 6, left). Based on previous research, this study identifies the Atayal weaving culture and cultural object (weaving loom), in terms of both gender identity among Atayal females and the collective ethnic identity of the Atayal.

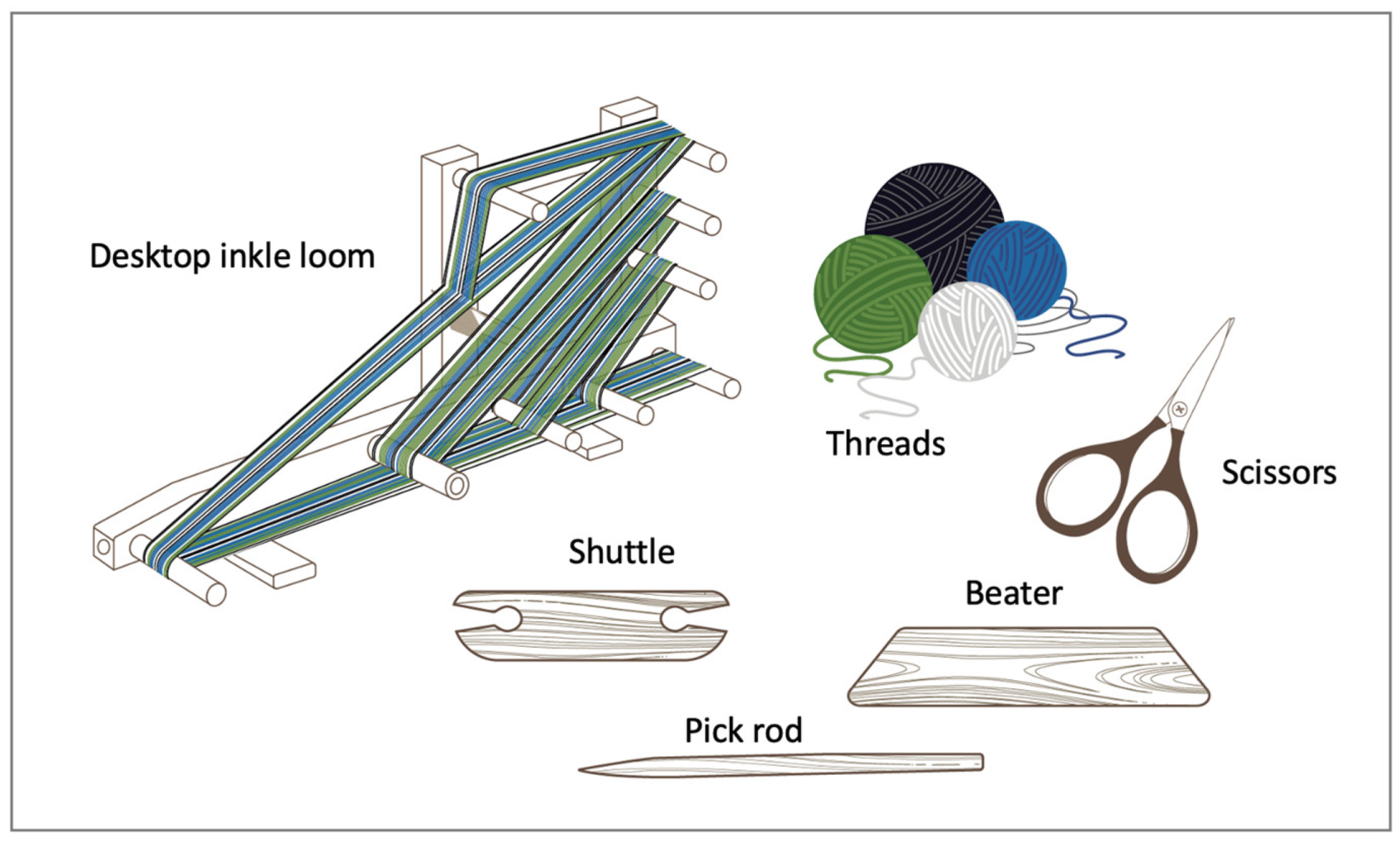

- Translation: Based on the cultural ergonomics approach, this study analyzes the interrelations between the cultural subject (Atayal weaver), cultural object (loom), and cultural activity (weaving) from the three aspects of user, tool, and task. Integrating the historical and contemporary understanding of cultural heritage in Atayal weaving, researchers and designers extract cultural features as design information and translate them into adoptable design elements in the translation step, as shown in Figure 6. Before weaving on a loom, the traditional Atayal preparations (planting the ramie, harvesting, stripping, spinning, poaching, dying, sun curing, sorting, etc.) require laboring and toiling with mind and body, undoubtedly taking much time. As a result, school instructors can only teach students vertical thread sorting and simple weaving procedures on a modern loom. Due to the practical limitations (time, space, budget, etc.), a simple device such as a desktop Inkle loom (Figure 4) is convenient and suitable for teaching weaving in school or a workshop.

- Implementation: Following the cultural ergonomics approach, this study redesigns a cultural product (Figure 6, right). The authors intend to inherit and transfer the box form and function to fulfill the appearance, storage, and portability connections between the original loom (cultural object) and creative box (cross-cultural product). In addition, while the lozenge on the cap of the outer box is used functionally as a grip handle, it additionally suggests the eye of the ancestors, which has great symbolic spiritual meaning. This single diamond shape with red striped patterns and decoration with a red frame carries ritual and religious meaning, and is an essential cultural signification in Atayal tradition. The user can manually assemble and install this re-designed product with the simpler weaving apparatus. This study demonstrates three steps of design transformation from a traditional Atayal warp case to a modern weaving box (Figure 6).

3.3. Evaluation Methods and Processes

- Surveyed schoolchildren: In this study, five aboriginal schoolchildren were invited for the evaluation, and ae coded as A, B, C, D, and E. Schoolchildren A and B were ten-year-old girls; C and D were nine-year-old girls; and E was an eight-year boy. It was the first time for all five schoolchildren to operate the modern weaving box and New Zealand mini-ribbon loom.

- Evaluation samples: This experiment evaluated a modern weaving box and a New Zealand min- ribbon loom. The bodies of both looms are made of wood, while certain parts are metal; the appearance and dimensions are shown in Table 1.

- Focus group: One Atayal teacher with more than twenty years of weaving and teaching experience, one designer with standing industry experience in product design, and five senior experts with academic and empirical backgrounds in cultural education, cultural research, and creative industry design were involved in this consulting committee.

- Evaluation objectives: Based on the records and descriptive documentation, seven experts reviewed the experiment of five schoolchildren’s operation of both looms. They aimed to evaluate the efficiency of the redesigned weaving box and its effectiveness as a teaching aid for cultural education.

4. Results

4.1. Feedback from the Schoolchildren

- Do you think the operation process is complex?

- Do you think it is hard to operate the ribbon loom, and where do you think it is hard to use?

- Which ribbon loom do you think works fine?

- Other feedback: Other responses and feedback to the modern weaving box included comments on the roughness caused by its handcrafted fabrication, defects in mutual conjunction, space between cylinders, length of the banister, stability of the loom, size of sheds, and storage. Selected descriptions are as follows for reference.

- When a ribbon box is expanded for use, and the user feels that the pull-out is not smooth, the reason being that the wooden materials are handcrafted. There are defects in positioning the cylinder used to manage the braids and box hole. Further fine grinding is required according to the tensile strength of the cylinder.

- During weaving, there is incline from heavy stress due to the different bearing capacities of the cylinders used for winding. The space between cylinders needs to be adjusted to enhance the stress level.

- The banister is too short to reach the optimum comfortable, scale and cannot fully satisfy users, especially in length.

- In observing the schoolchildren using the ribbon looms, it was found that the ribbon looms waggle, slide, and even incline; hence, the future design should increase their stability.

- During weaving, sheds must be expanded to make the weft shuttle pass through more easily. During use, it was found that the schoolchildren would turn their heads sideways to find the sheds (Figure 10), causing neck fatigue and discomfort.

- The adjustable bar, support bar, harness bar, and weaving tools can be stored in the redesigned modern weaving box after weaving. However, the semi-finished weaving cannot be stored in the box together, which reduces the originally-designed storage effects.

4.2. Feedback from the Schoolteacher and Experts

- Which loom is easier for schoolchildren to operate and weave?

- Does the redesigned weaving box facilitate the weaving learning of cultural education?

- What will be the schoolteachers’ primary concern, demand, or challenge when executing the weaving learning for cultural education?

5. Discussions

- From Nature to Culture

- From Passion to Expectation

- From Traditional to Creative

- From Living to Pleasing

- From Circle to Cycle

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Development Council. National Strategy for Regional Revitalization. 2022. Available online: https://www.ndc.gov.tw/Content_List.aspx?n=78EEEFC1D5A43877 (accessed on 28 March 2022).

- Yang, C.-H.; Sun, Y.; Lin, P.-H.; Lin, R. Sustainable development in local culture industries: A case study of Taiwan aboriginal communities. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafi, B.; Kloos, M.; Neugebauer, C. Heritage impact assessment, beyond an assessment tool: A comparative analysis of urban development impact on visual integrity in four UNESCO world heritage properties. J. Cult. Herit. 2021, 47, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Lin, C.; Zheng, X. Case study of local revitalization in Indigenous areas of Taiwan: Using the Namasia District as an example. Open J. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.-L.; Hsu, J.-Y. From cultural building, economic revitalization to local partnership? The changing nature of community mobilization in Taiwan. Int. Plan. Stud. 2022, 16, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, J.H.; Lin, S.; Lai, S.; Huang, Y.; Yi-fong, C.; Lee, Y.; Berkes, F. Taiwanese Indigenous Cultural Heritage and Revitalization: Community Practices and Local Development. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillies, C.L.; Crawford, C.; Hancock, B. Restoring Angasi oyster reefs: What is the endpoint ecosystem we are aiming for and how do we get there? Ecol. Manag. Restor. 2017, 18, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, I.; Schmider, J.; Gillies, C. Seven pearls of wisdom: Advice from Traditional Owners to improve engagement of local Indigenous people in shellfish ecosystem restoration. Ecol. Manag. Restor. 2018, 19, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Council of Indigenous Peoples. The Tribes in Taiwan: Atayal. 2021. Available online: https://www.cip.gov.tw/en/tribe/grid-list/A7F31083995F0E60D0636733C6861689/info.html?cumid=5DD9C4959C302B9FD0636733C6861689 (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Wang, W.-C. The Ritual Pageants of Taiwan Indigenous Tribes, 1st ed.; SMC Publishing: Taipei, Taiwan, 2004; pp. 185–192. [Google Scholar]

- Jeannotte, M.S. Caretakers of the earth: Integrating Canadian Aboriginal perspectives on culture and sustainability into local plans. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2017, 23, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Zhu, S.; Li, W. Promoting Sustainable Creativity: An Empirical Study on the Application of Mind Mapping Tools in Graphic Design Education. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.; Akgunduz, A.; Zeng, Y. Design education: Learning design methodology to enrich project experience. In Proceedings of the Canadian Engineering Education Association (CEEA-ACEG) Conference, Toronto, ON, Canada, 18–22 June 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, I.-Y.; Lin, P.-H.; Kreifeldt, J.G.; Lin, R. From Theory to Practice: An Adaptive Development of Design Education. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreifeld, J.G.; Gao, Y.; Yang, G.; Yen, H.; Taru, Y.; Lin, R. A study of cultural ergonomics in Atayal weaving box. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference, CCD 2019, Held as Part of the 21st HCI International Conference, HCII 2019, Orlando, FL, USA, 26–31 July 2019; pp. 170–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.L.; Chen, S.J.; Hsiao, W.H.; Lin, R. Cultural ergonomics in interactional and experiential design: Conceptual framework and case study of the Taiwanese twin cup. Appl. Ergon. 2016, 52, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taru, Y.; Kreifeldt, J.G.; Sun, M.; Lin, R. Thoughts on studying cultural ergonomics for the Atayal loom. In Cross-Cultural Design; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, M. Weaving and Identity of the Atayal in Wulai, Taiwan. Master’s Thesis, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON, Canada, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura, M.; Wall, G. Weaving as an Identity Marker: Atayal Women in Wulai, Taiwan. J. Res. Gend. Stud. 2014, 4, 171–182. [Google Scholar]

- Nettleship, M.A. A unique South-East Asian loom. Man 1970, 5, 686–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, I.-Y.; Lin, R.; Lin, P.-H. Placemaking with creation: A case study in cultural product design. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference, CCD 2021, Held as Part of the 23rd HCI International Conference, HCII 2021, Washington DC, USA, 24–29 July 2021; pp. 244–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-R. Atayal: A tribe famous for the weaving and facial tattoo. In Knowing Indigenous People in Taiwan, 1st ed.; Cultural Industry Development Association of Taiwan Indigenous People: Taipei, Taiwan, 2007; pp. 34–81. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, J.; Wall, G.; Chang, C. Perception of the authenticity of Atayal woven handicrafts in Wulai, Taiwan. J. Hospit. Leis. Mark. 2008, 16, 385–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y.-T. The Society and Culture of Austronesian in Taiwan, 1st ed.; National Museum of Prehistory: Taipei, Taiwan, 2006; pp. 45–56.

- Wang, C.-F.; Tung, H.-C. A discussion of the conflicts of regulation between the nation and tribes and the reaction in the future by the hunting culture of the Indigenous peoples. Taiwan J. Indig. Stud. 2012, 14, 39–72. [Google Scholar]

- Kreifeldt, J.G.; Taru, Y.; Sun, M.; Lin, R. Cultural ergonomics beyond culture—The collector as consumer in cultural product design. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference, CCD 2016, Held as Part of the 18th HCI International Conference, HCII 2016, Toronto, ON, Canada, 17–19 July 2016; pp. 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreifeldt, J.G.; Hill, P.H. The integration of human factors and industrial design for consumer products. Proc. Hum. Factors Soc. Annu. Meet. 1976, 20, 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreifeldt, J.G. Consumer product design projects for human factors classes. Proc. Hum. Factors Soc. Annu. Meet. 1982, 26, 735–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreifeldt, J.G.; Hill, P.H. Toward a theory of man-tool system design applications to the consumer product area. Proc. Hum. Factors Soc. Annu. Meet. 1974, 18, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R. Transforming Taiwan aboriginal cultural features into modern product design: A case study of a cross-cultural product design model. Int. J. Des. 2007, 1, 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, R.; Lin, P.-H.; Shiao, W.; Lin, S. Cultural aspect of interaction design beyond human-computer interaction. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference, IDGD 2009, Held as Part of the 13th HCI International Conference, HCII 2009, San Diego, CA, USA, 9–14 July 2009; pp. 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, T.Y.; Cheng, H.; Lin, R. A study of cultural interface in the Taiwan aboriginal twin-cup. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 22–27 July 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, R.; Kreifeldt, J.G. Ergonomics in wearable computer design. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2001, 27, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-H.; Chang, S.-H.; Lin, R. A Design Strategy for Turning Local Culture into Global Market Products. Int. J. Affect. Eng. 2013, 12, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, S.L. Garments culture of Taiwan aborigines. Hist. Objects 2000, 87, 14–28. [Google Scholar]

- Murovec, N.; Prodan, I. Absorptive capacity, its determinants, and influence on innovation output: Cross-cultural validation of the structural model. Technovation 2009, 29, 859–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, D.A. Emotional Design: Why We Love (or Hate) Everyday Things; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.J.; Chang, W.; Fang, W.; Lin, R. Acculturation in human culture interaction—A case study of culture meaning in cultural product design. Ergon. Int. J. 2018, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piegorsch, K. An ergonomic bench for Indigenous weavers. Ergon. Des. Q. Hum. Factors Appl. 2009, 17, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaman, R.; Aliyari, R.; Sadeghian, F.; Shoaa, J.V.; Masoudi, M.; Zahedi, S.; Bakhshi, M.A. Psychosocial Factors and Musculoskeletal Pain Among Rural Hand-woven Carpet Weavers in Iran. Saf. Health Work 2015, 6, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Durlov, S.; Chakrabarty, S.; Chatterjee, A.; Das, T.; Dev, S.; Gangopadhyay, S.; Sahu, S. Prevalence of low back pain among handloom weavers in West Bengal, India. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Health 2014, 20, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Roth, H.L. Studies in primitive looms. J. R. Anthropol. Inst. Great Br. Irel. 1918, 48, 103–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowfoot, G.M. Of the warp-weighted loom. Annu. Br. Sch. Athens 1937, 37, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faxon, H. A model of an Ancient Greek loom. Metrop. Mus. Art Bull. 1932, 27, 70–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broudy, E. The Book of Looms: A History of the Handloom from Ancient Times to the Present; UPNE: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.H. The Characteristics of Taiyal Weaving as an Art Form. Doctoral Dissertation, Durham University, Durham, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura, M.; Wall, G. The Reconstruction of Atayal identity in Wulai, Taiwan. In Heritage Tourism in Southeast Asia; Hitchcock, M., King, V.T., Parnwell, M., Eds.; NIAS Press: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2010; pp. 49–71. [Google Scholar]

- Hualien Cultural Memory Bank. Mini Inkle Loom. 2019. Available online: https://culture.hccc.gov.tw/zh-tw/archives/detail/artwork-3864 (accessed on 7 April 2022).

- Patrick, J. The Weaver’s Idea Book: Creative Cloth on a Rigid Heddle Loom; Interweave Press (F + W Media): Loveland, CO, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Aitken, I.A. Weaving with Inkle and with cards. Design 1942, 43, 14–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, N. Inkle loom weaving. Design 1975, 77, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koster, J.B. From Spindle to Loom: Weaving in the Southern Argolid. 1976. Available online: https://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/from-spindle-to-loom/ (accessed on 7 April 2022).

- Guttentag, D. The legal protection of indigenous souvenir products. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2009, 34, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varutti, M. Crafting heritage: Artisans and the making of Indigenous heritage in contemporary Taiwan. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2015, 21, 1036–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.; Goulding, A.; Whitehead, C. Contemporary visual art and the construction of identity: Maintenance and revision processes in older adults. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2014, 20, 432–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.-Y.; Pan, Y.-F. A study of Atayal weaving knowledges with the talent development, ethnic conscience and cultural identification. Taiwan Indig. Stud. Rev. 2010, 7, 209–242. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, M. Introduction: Adding a cultural dimension to human factors. In Cultural Ergonomics 4; Kaplan, M., Ed.; Elsevier: Kidlington, UK, 2004; pp. XI–XVII. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, Y.-C. Atayal Weaving Handcrafts Business Model—The Case Study of Lihang Studio. Master’s Thesis, National Tsing Hua University, Hsinchu, Taiwan, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lihang Studio. Atayal Dyeing and Weaving Cultural Park. 2022. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/lihangworkshop (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Lin, R.; Kreifeldt, J.G. Do Not Touch: Dialogues between Dechnology and Humart; National Taiwan University of Arts: New Taipei, Taiwan, 2014; pp. 129–144. [Google Scholar]

| Loom Type | Dimension (cm) (Length × Width × Height) | Appearance |

|---|---|---|

| Redesigned Modern Weaving Box | Outer Box (36.6 × 13 × 5) |  |

| In Use (36.6 × 23 × 14.5) |  | |

| New Zealand Mini Ribbon Loom | In Use (38 × 11 × 17) |  |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, R.; Chiang, I.-Y.; Taru, Y.; Gao, Y.; Kreifeldt, J.G.; Sun, Y.; Wu, J. Education in Cultural Heritage: A Case Study of Redesigning Atayal Weaving Loom. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 872. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12120872

Lin R, Chiang I-Y, Taru Y, Gao Y, Kreifeldt JG, Sun Y, Wu J. Education in Cultural Heritage: A Case Study of Redesigning Atayal Weaving Loom. Education Sciences. 2022; 12(12):872. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12120872

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Rungtai, I-Ying Chiang, Yuma Taru, Yajuan Gao, John G. Kreifeldt, Yikang Sun, and Jun Wu. 2022. "Education in Cultural Heritage: A Case Study of Redesigning Atayal Weaving Loom" Education Sciences 12, no. 12: 872. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12120872

APA StyleLin, R., Chiang, I.-Y., Taru, Y., Gao, Y., Kreifeldt, J. G., Sun, Y., & Wu, J. (2022). Education in Cultural Heritage: A Case Study of Redesigning Atayal Weaving Loom. Education Sciences, 12(12), 872. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12120872