Abstract

This qualitative case study investigates the rationales, dilemmas, and shortcomings of the so-called “inclusion-promoting steering models” in which Danish schools have to pay a price for every student they cannot include in their school. For more than 10 years, the government has promoted such financial steering models and a rising number of municipalities have adopted the system, so that more than one-half of the existing Danish municipalities work with them. According to its advocates, this model supports the inclusion of students in schools in several direct ways. This case study shows that this model is based on some strong rationales, as it offers opportunities to promote the development of inclusive schools. However, the study also reveals that this comes at a price, as the model sometimes poses difficult dilemmas on school leaders and hinders the inclusion of all students.

1. Introduction

Building an inclusive learning environment in school refers to more than just physical access and the provision of support to students with different disabilities. Rather, it concerns a profound change of the school system where schools alter their organisations and practices in ways that will support the active participation of all children [1]. Sometimes, attending to and providing for every child’s needs in a school system requires extra resources such as extra personnel, assistive devices or accommodations. For example, the presence of two teachers in one classroom can be crucial to support the participation of a diverse group of students. This means that the amount of resources and the financial system underlying the provision of school services can be a significant factor in realising a school for all children. In the case of Denmark, the institutional organisation of a financial system allegedly supporting inclusion has played an important role for more than 10 years. Back in 2010, the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Education, and other partners analysed how Danish municipalities organised school funding, including the funding of special educational support [2]. They found that the way the municipalities organised their financial systems in the school area in itself hindered the effective development of an inclusive school. Furthermore, they mentioned that the common financial system of the school area seemed to be an underlying reason why the mainstream school system segregated more and more students into special classes and special schools. To counteract this tendency, the ministries recommended a system called the inclusion-promoting steering model that called for the municipalities to strengthen schools’ incentives to provide services for students in mainstream classrooms ([2], p. 25). Since then, more and more municipalities in Denmark have chosen to change their financial systems to conform to this model. This means that at present, more than one-half of all municipalities in Denmark work with financial systems in which incentives to include students in mainstream classrooms play a key role. Hence, it is interesting to investigate the rationales that the municipal administrative leaders use when making decisions about transitioning to this financial system and the positive consequences they, along with the school leaders, foresee or experience in this respect. However, it is also a basic fact of the system that it puts economic pressure on school leaders if they choose to (or find that they have to) segregate students from mainstream schools to special educational schools or special classes. This may pose significant dilemmas on school leaders if, for instance, the school in question finds it difficult to provide the best support for a student in need and, at the same time, has difficulties finding financial opportunities to pay for the needed support outside school. Hence, the following two research questions of this interview-based case study is:

- What are the rationales of the “inclusion-promoting steering models” from the perspectives of the municipal and school leaders?

- What dilemmas does the model pose to school leaders?

2. Background—Introduction and Growth of the Model

Over the last decade, an increase has been noted in the number of Danish municipalities that have changed the financial system of their school districts [3]. In 2010, a rapidly rising number of students referred from mainstream classes to special classes or schools spurred this change [2,4]. This development was considered troubling in terms of the educational ideals of building an inclusive school system that offers the necessary help and support in mainstream classrooms to a vast majority of children [1]. Furthermore, this development increasingly became troubling in terms of the economy, as the support offered in special schools or classes is several times more expensive than that in mainstream classrooms [5]. In 2010, the Danish Ministry of Finance, the Danish Ministry of Education, and other partners formed a committee and analysed the situation. The committee scrutinised the way Danish municipalities had organised the financial system in the school area. They found that the organisation of the school finances played a key role in increasing segregation from mainstream schools, as the setup was not found to be conductive of the development of inclusive learning environments. At the same time, they concluded that referring students to special schools or classes was free of financial consequences for mainstream schools, as the municipality had separately allocated extra funds for expenditures on such arrangements.

“…schools rarely pay a noteworthy part of the expenditures for the students being referred to segregated special schools and classes. This means, that schools most often do not feel the expenditure-wise consequences for the municipality. The committee finds, that the high degree of segregation [of children from mainstream schools to special support venues] might be due to the fact that it is costly for schools to include students with special needs, and, at the same time, free of charge to seek that these students are transferred to segregated special schools and classes. In other words, the steering- and budget models are a contributing cause…”([2], p. 25).

The 2010 report scrutinised and outlined the organisational details of the financial steering systems in 12 representative municipalities. A conclusion common to all these municipalities was that virtually the entire budget for financing special educational support was centralised at the municipality level. This organisation implied that when a student was shifted from a mainstream classroom to a special school or class, the extra expenditures for this arrangement had to be paid by a pool of finances at the municipality level, and the school would pay nothing or very little. This meant that schools were not encouraged to work toward inclusion at all, for instance, through arranging accommodations for students in the learning environment, as this would increase school’s expenditures in addition to their ordinary school budget.

“The budget models in the 12 municipalities are fairly centralised, and none of the municipalities have fully decentralised the financial responsibility for special educational support to the schools. Because of this, the present models do evidently not encourage schools to include students”(Ibid., p. 18)

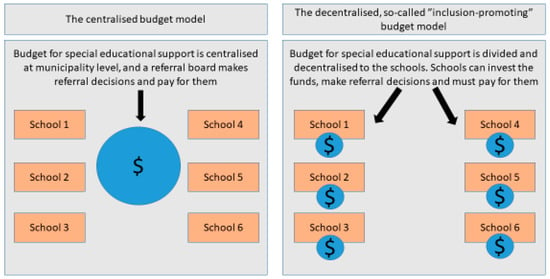

According to the ministerial report, the alternative to this centralised budget model is to let the schools pay a part of or all of the expenditures when a student is referred to special support outside the mainstream school system. As a pre-requisite for this model, the municipality must divide the budget for special educational support and then decentralise these funds to schools across the municipality in advance, for example before the beginning of the school year. On the one hand, this model provides larger funds to schools that can choose to use some of these funds to invest in building an inclusive environment in mainstream schools. For instance, through hiring more teachers or social educators, arranging more lessons with two teachers in one classroom at the same time, arranging special support groups or investing in physical accommodations in the classrooms to meet the needs of all students. On the other hand, this model means that the singular school must also carry the financial burden if it chooses to refer a student to a special school or class. Figure 1 illustrates the differing principles of the aforementioned two budget models.

Figure 1.

The centralised and decentralised budget models at a glance.

Under the heading “Inclusion-promoting steering models”, the ministerial report explains the model and recommends it as follows:

“The committee suggests that (…) the municipalities to a greater extent lets the schools pay a part of the expenditures to the students being referred to segregated support [in special schools or special classes] which is accompanied by a previous increased decentralisation of the budgets”(Ibid., p. 25).

Different budget models and their effects have been investigated and discussed extensively in the international research literature, especially in the American and Canadian contexts. Based on data from Texas school districts, Cullen investigated the connection between school-financial incentives in the form of larger state revenues and the number of students classified as disabled, who enrolled in special education.

“The results indicate that local responses to state incentives play an important role in determining the ultimate size of special education programs, and therefore, in determining the allocation of resources within and across schools. I find that a 10% increase in the supplemental revenue generated by a disabled student leads to approximately a 2% increase in the fraction of students classified as disabled”([6], p. 1559).

Concurrently, Greene argues that schools in several American states have this type of incentive to over-identify students with learning disabilities, as school finances are connected to the number of students with special needs: “[t]he incentive to over-identify is caused by providing schools with additional funds as more students are placed in special education categories…” ([7], p. 703). Based on data from several US states, Greene and Forster (2002) investigated the effect of the funding system on the number of students enrolled in special education programmes. They conclude that there is a strong connection:

“State funding systems are having a dramatic effect on special education enrollment rates. In states where schools had a financial incentive to identify more students as disabled and place them in special education, the percentage of all students enrolled in special education grew significantly more rapidly over the past decade”([8], p. 8).

Wishart and Jahnukainen (2010) found the same linkage in the school funding system in Alberta, Canada. In the Alberta system, schools receive extra funding according to a set of codes for student disabilities, where more severe disabilities lead to higher funding. As the authors write, “[i]t is obvious that the current Alberta special education coding system provides chances for schools to (…) ‘upgrade’ students to a better funded category” ([9], p. 186). Several American states have introduced incentives for schools to attend to students’ special needs in mainstream classes instead of doing so in special educational programmes, and Kwak investigated the effects of such incentives. Based on register-based data from California, the study concluded that referral rates and disability rates seem to be affected by the introduction of incentives in the financial systems of school districts. Kwak notes in the following excerpt:

“… changes in the price of special education have a negative effect on disability rates and a negative effect on total state special education classification. In other words, when the price of special education increases, as it did for all districts in California, the quantity of students classified as disabled falls”([10], p. 64).

Regarding the conclusions and recommendations by the Danish ministries, these studies seem to indicate that there might be a connection between the construction of the financial system and the number of pupils that schools choose or do not choose to include. In the years following the 2010 report from the Danish ministries, many Danish municipalities chose to follow the recommendation to adopt the decentralisation of special educational budgets for schools, thereby strengthening incentives for inclusion. Though none of the twelve representatively chosen municipalities had established this financial setup at the beginning of 2010, more and more municipalities proceeded in this direction and adopted a decentralised system. By 2019, the balance tipped and 51% of all Danish municipalities had adopted the system and decentralised their budget for special educational support to schools, whereas 49% of them still followed the traditional centralised budget model [11]. In 2021, the pattern continued and 57% of all Danish municipalities had adopted decentralised budgets, whereas 43% continued to follow the centralised model [5]. This strong pattern causes it to be imperative to investigate further details of the consequences of the model in practice for the schools working with it and the real-life pros and cons of the increasingly popular model. The research questions of this study stem from the aforementioned aims of the investigation.

3. Data and Methods

This qualitative case study builds on interviews of school leaders and municipal administrative leaders conducted across the years 2019, 2020, and 2021. These were semi-structured interviews [12], in which 11 municipal administrative leaders were interviewed; out of these, 7 were from municipalities working with the decentralised budget model and 4 were from those working with the centralised budget model. In addition, interviews of 16 school leaders were used, out of which 10 worked with decentralised budget models and 6 worked with centralised budget models. All interviews were audio recorded, generating approximately 27 h of recorded material. This material was transcribed in Danish. Transcript symbols can be seen in Appendix A. The resulting transcripts were coded according to the study’s two research questions. This constructed a focused data set, which was later analysed qualitatively, focusing on bringing forward the rationales as well as the dilemmas of the two budget models according to the participating leaders. The author conducted all coding and analysis. The excerpts used in this study have been translated into English.

All the participants were informed of the purpose of the study and accepted to participate and all data were gathered, stored, and analysed in accordance with the European General Data Protection Regulation [13]. To protect the anonymity of participants, information such as names, places, and so forth have been deleted or modified, and all municipalities are anonymised as well.

Regarding the interpretation of the results, it is important to underscore that the study is a qualitative interview-based case study with a limited number of participants. Therefore, generalisation should be done with caution. In addition, it is noteworthy that the purpose of this study was not to represent, for instance, the perspectives of all Danish school leaders or municipal leaders working with different types of budget models, but rather to explore the types of rationales, dilemmas, and the nature of arguments that our participants put forward in the conducted interviews.

4. Results of the Study

In this section, the results of the study are presented in the following two sections. Section 4.1 scrutinises the rationales of the decentralised budget model as accounted by municipal and school leaders, while Section 4.2 analyses the dilemmas and shortcomings of the model as accounted by municipal and school leaders.

4.1. Rationales of the “Inclusion-Promoting” Budget Model as Accounted by the Leaders

Several of the interviewed municipal administrative leaders and the school leaders expressed quite frankly that the decentralised budget model works through the creation of an incentive for school leaders. That is, a central built-in force in the budget model is that it works by putting financial pressure on the individual school leader if the latter chooses to refer a student out of the mainstream school. This mechanism is often expressed as quite straightforward as shown in the excerpt below:

“Every time they cannot make it work in their school, they have to pay this price for it.”(Municipal administrative leader, Municipality 1, 2020, p. 8)

The size of “the price” that the school must pay differs from one municipality to another; however, it typically ranges from double to five or six times the price of having a student in a mainstream class. In Denmark’s context, the typical expenditures that mainstream schools have for a student is about DKR 60.000–70.000 (about USD 8.600) per year, whereas the average expenditures for a student in a special school is about DKR 430.000 (about USD 57.300) per year [5]. The simple logic of the system is that the school leaders pay out of their budgets from double to six times the expenditure for the student, if the student is referred to a special school. However, at the same time, this also means that it is profitable for the school if it is possible to create in-school accommodations to meet the needs of the student for less than this price, which, of course, creates a rather large scope for opportunity to adopt the learning environment to the needs of all students. A school leader elaborates on how the model creates an incentive to create local accommodations and in-house support for all students, as this might prevent the school from paying the expenditures for segregation from a mainstream school to a special school or class:

“It is also a part of the incentives of the model that instead of spending DKR 250.000 [about USD 33.300—the price in this particular municipality] off with a student (…) we might, if we have a few students with similar needs, spend the money more effectively in house. In fact, that is the core of steering logic. We should act in this way. It is a common practice.”(School leader, Municipality 3, 2019, p. 4)

As the school leader explains in the previous excerpt, it has become a common organisational solution in Danish mainstream schools to form a small special support group with a number of students with similar needs, which is supported and promoted by the financial structure. The in-school special support groups can, for instance, target the needs of a number of students who need close support in a number of subjects, but who are a part of their mainstream classes for the rest of the school day. The rationale for this specific setup is that by putting together a number of students with similar needs, the economy bound in working hours for the staff teaching this group produces more hours of support than if the students were supported individually in the individual mainstream classrooms of which they are a part. As a simple and straightforward example, if five students in five different classrooms need specialised support in three hours per week, this would demand five times three working hours if an extra teacher were to go into each different classroom, whereas if the group of five students are gathered in a small group, it only demands three hours in total. Although this simple logic is a widely adopted strategy in Danish schools at present, it can sometimes be challenged in real-life school settings. As several school leaders underscore, the extra finances that are decentralised and added to the ordinary school budget allows for the development of a much wider range of accommodations than the pool of finances for special support still centralised at the municipal level. In a certain sense, the change in the financial steering logic has been a part of, and often a direct pre-requisite for, a change within the Danish school system, where the boundaries between mainstream school and special support within special schools and classes are increasingly blurred. As one school leader expressed, the economy makes way for a kind of hybridisation between ordinary and special schools:

“I think that we are inventing hybrid models [between mainstream school and special school] at the local level (…) and we are actually quite good at changing form and structure all the time, based on the needs of the children”(School leader, Municipality 3, 2019, p. 1).

This school leader also argued that the local development of hybrid models is made possible by the decentralised economy of the schools. This model also suggests that schools make decisions in-house regarding which students should attend what groups or kinds of support and for how many hours. As the school leader says, they are as school leaders better allowed to change the structure all the time based on the needs of the students, instead of having to go through a time-consuming referral system in the centralised model with a referral committee at the municipal level.

In contrast, there are still a number of municipalities working with the centralised budget model. The school leaders and municipal administrative leaders working under this model often mentioned the built-in limitations of this other model. This is, for instance, the case in the following excerpt from an interview with a municipal administrative leader reflecting on the current state of affairs in their municipality:

“… regardless of whether you like it, there are no incentives in the structure at all … it does not cost the schools anything to send in an application to the referral committee. This means that there is nothing—you are basically not animated to say “Could we do something else, that is, make some efforts, some [support in school]” (…) It is free of charge to send a Christian into referral and have him removed [from mainstream school] … the money, that at present is lying here with me [at the municipal level], you know, it should be out, working (…) in mainstream schools”(Municipal administrative leader, Municipality 2, December 2020, p. 3–4).

As the municipal administrative leader frames the matter in the previous excerpt, it is underscored how the pool of finances in the centralised budget for special educational support is a passive resource. The money is “lying here with me” when “it should be out, working” for and be put to use instead in the mainstream schools to build accommodations to meet the needs of all students.

Another municipal administrative leader pointed out how the traditional centralised model seems to create counterproductive incentives in regard to inclusive school development: decisions to shift a student from a mainstream school are financially rewarded (as the municipality pays for these). In addition, decisions to try to create an inclusive environment that would suit the needs of a student with special needs are financially punished (as the school leader has to pay for this out of his or her own budget, which at the outset is smaller because of the centralised special educational budget).

“… our financial incentives are horrible, you know, the only thing that pays off is to send a child into a special school. You do not want to put money on the table yourself. (…) This means that it is totally and completely free for a school leader to segregate a child.”(Municipal administrative leader, Municipality 4, 2019, p. 8)

The interviewed leaders pointed out a consequence of the traditional centralised budget model and the limited budgets that mainstream schools have in this setup. As already mentioned, it is a part of this setup that schools have to send in a request to have a student segregated to a municipal referral committee when they experience that the student’s problems are beyond what they are able to work with in school. However, this procedure often requires some time, as a request requires a pedagogical-psychological evaluation and the student’s problems should be significant enough before deciding on a referral application. Because of this, students’ problems are sometimes left unattended and just grow bigger before the cases are brought up at a referral meeting. As the municipal administrative leader in Municipality 3 pondered, this entails a risk that the institutional setup itself sometimes contributes to a delay in interventions, leading to escalation of the student’s problems, in comparison to the case of the budgets allocated in advance to the schools by decentralisation.

“In those cases, you might say: (…) Are we actually ourselves producing some of the children that are not thriving?”(Ibid., p. 5)

This indicates a core problem associated with the traditional organisation of the special education budget: budgets for support are passive and lie waiting at the municipal level until student’s problems reach a point where the student often has to be moved from the mainstream school. The possibilities of building accommodations to suit the needs of all students within the mainstream are limited to the mainstream school budget.

4.2. Dilemmas of the “Inclusion-Promoting” Budget Model as Accounted by the Leaders

The previous section mentioned a number of important advantages of the decentralised budget model and pointed out how the model avoids some of the shortcomings of the traditional centralised budget model. However, at the core of the model lies a potential problem built into the effective financial incentives. The problem is that if a school ends up segregating more students than they can afford within the decentralised part of the budget for special educational support, they might find themselves forced to cut the budgets of the mainstream school. At the decentralised level of an individual school, there is only one budget for the school leader, meaning that the funds for the mainstream school and the funds for special educational support work as two connected vessels. This means that mainstream classes, the teachers teaching them, and the students attending them might end up paying the price for other students’ support. Several school leaders point to this mechanism as a dilemma between the mainstream part and the special part of the school. In several municipalities represented in this study, one or more schools ended up having troubles because they spent too much of their budget on paying for special educational support. As a municipal administrative leader explained, there is a risk of sliding into what he called “a vicious circle”:

“…some [school leaders] move more children [to special schools or classes] than they can afford. (…) And the problem is that if you get a negative result on the bottom line, or get close to zero, then you are not able to invest in building [inclusive] environments in your school. This turns into a vicious circle because it means that you are going to send even more students to special support premises. (…) If they don’t control that part of the economy, then it is going to have severe consequences for their ordinary classes.”(Municipal administrative leader, Municipality 5, 2019, p. 5)

As the municipal leader explains, if you, as a school, end up segregating too many students (whom the school leader pays for in the decentralised model) for support, you might be forced to cut back the budgets of the mainstream classrooms, which also often means cutting back the capacity to attend to all of the students’ needs. This might mean that, over time, even more students must be sent off to special schools or classes, strengthening the pressure on the school’s budget—and the vicious circle continues.

How does this look from the perspective of one of the school leaders involved in this situation? In the following excerpt, a school leader explained how they had to gradually cut back the resources in terms of two teachers in the same classroom, co-teaching, and division of classes during lessons, as more and more students were being put in special support groups or segregated to special premises outside school.

“… the economy is not enough regarding the needs. This means that co-teaching in the ordinary classes … [pauses]. Early on, we had more lessons with two teachers, but they were pulled out and sent to [the special support groups]. Actually, all resources for co-teaching and division of classes during lessons and so on have gone into [the special support groups]. This means that, as a student in an ordinary class with 26 students, you must be in the large group the whole time. This becomes a problem for some of the students, with the result that we indirectly exclude some over time.”(School leader, Municipality 6, 2019, p. 3)

As the school leader pointed out, the mechanism of the incentive has led to a situation in which they must stop two-teacher lessons and division of classes (also demanding two teachers) during lessons, as the special support groups swallow up more and more resources. As the leader argued, this leads to a situation where all mainstream classroom lessons are taught by only one teacher and this limits the scope and opportunities for attending to every student’s needs. Furthermore, the leader argued that the unattended needs of some students in these classes continue to increase up to a point at which they are also excluded and put in a special support group—the “vicious circle” as mentioned by a municipal administrative leader. Another school leader pointed out that this actually indicates a risk that it is the students in mainstream classes who eventually pay the price that is built into the incentive-driven decentralised budget model.

“In a direct manner, you can say that it might be the children who pay for some of this. The well-functioning children—that is. For in this setup, it is all the children with difficulties who receive the support that they should have—so the money wanders in that direction, you might say.”(School leader, Municipality 18, 2021, p. 5)

The earlier quoted school leader in Municipality 3, who experienced the built-in dilemmas of the model, reflected on the fairness of the model as well as what the consequences in the long run might be as follows:

“It makes me fear for the future of the common school … that the children who are just competent in the school subjects and function well in the social peer groups will not be able to receive enough because all of the resources go to the special area. (…) How are you supposed to stimulate the skilled students when all the time goes to the ones with problems? (…) The [special support groups] swallow up everything …”(School leader, Municipality 18, 2021, p. 7)

As observed, according to municipal administrative leaders in municipalities that have not decentralised funds to schools, there is significant pressure from schools to have students segregated to special educational premises. This clearly makes controlling the economy at the central level difficult in the centralised model, as there is always a risk of spending too many resources on special educational support. According to some of the school leaders, it is also part of the rationale of decentralisation to shift this pressure from the municipality to schools. For instance, a school leader said:

“The intention [with decentralising the budget to the schools] was also that the municipality was not able to control the economy. Now, the pressure that used to lie at the municipal level has been shifted out on the school. Now, WE are caught in the dilemma.”(School leader, Municipality 8, 2019, p. 1).

As the school leader said in the previous excerpt, the choice of decentralising the budgets was selected because the municipality level had a hard time handling this dilemma. In a certain sense, one could say that decentralising does not necessarily solve the dilemma between balancing special support and mainstream schools (which is also a question of balancing the needs of all students). Rather, according to the accounts of our participants, it seems that it sometimes just moves from being a municipal dilemma to being an individual school leaders’ dilemma at the local level.

It is important to put forth one further built-in problem of the model. In the traditional centralised model, decisions to shift a child from mainstream to special educational support are made by a municipal referral board comprising specialists, such as educational psychologists and special educational consultants. However, when the budget is decentralised, such decisions move from the central municipal level to the individual school leader, causing the following question to be vital: do all individual school leaders possess the competencies to evaluate students’ special needs and the ability to make decisions about how to address students’ special needs? This does not seem to be the case. As one school leader briefly stated:

“But I simply have not … I do not have … I am not competent to make this decision on my own”(School leader, Municipality 18, 2021, p. 9).

Another school leader framed it even more directly as follows:

“You know, I do not have the competencies to say what kind of accommodation [the student needs]. So it makes me sit here, like, helpless and, of course, I can make a wild guess—well, then I will place the child here. However, I really need someone who, with stronger competencies within the field, is able to say, ‘This is what we will do’. In this respect, we are challenged by the way we have organised things today, I think”(School leader, Municipality 18, 2021, p. 10).

When decentralising the economy, decisions are made by the individual school leader instead of the referral board. However, this might lead to less precise decisions on how to accommodate the special learning needs of a specific student. This means that there is a risk of imprecise and less professional decisions in regard to how to attend to students’ needs when decisions move from a board of specialised professionals to school leaders, some of whom have limited or no professional knowledge or competence on the matter.

5. Concluding Discussion—Pros and Cons of the Decentralised Model

As the study has revealed, municipal and school leaders emphasise the following rationales and advantages of the decentralised budget model:

- When school leaders pay for support outside of their own budget, they become less inclined to refer students to support outside the school.

- Decentralised funds can be invested in creating inclusive learning environments in mainstream schools instead of the budget lying as a passive resource at the municipal level.

- This model causes it to be possible to accommodate the learning environment to students’ needs earlier on and prevent some of the situations that might mean that a student has to be removed from a mainstream classroom to more specialised support outside the mainstream classroom.

In contrast, the participants of the study also pointed to the following dilemmas and shortcomings pertaining to the model:

- If the school leader moves more students to special support than the decentralised budget can bear, the school might end up in a situation in which they have to cut back the budget of mainstream classes to finance the support group.

- This means that mainstream school students may ultimately pay the price for other students’ support. In addition, it means that the possibilities for attending to students’ different needs within mainstream classes are limited, leading to an increase in some students’ needs to a point where they also need to be removed from the mainstream class.

- As mentioned by the school leaders themselves, not all school leaders have the required competencies to make qualified decisions regarding what accommodations and arrangements will meet the needs of all students. This means that decentralising the budget leads to a risk of less qualified decisions regarding educational support compared to the decisions of the specialised group of professionals typically found on municipal referral boards.

As mentioned in Section 2, it was a central argument from the committee formed by Danish ministries right from the beginning that the decentralisation of budgets would cause school leaders to be less inclined to refer students out of school and increase the amount of resources available to them to build inclusive learning environments [2]. According to our participants, these advantages seem to be obvious consequences of the model when realised in real life.

However, the shortcomings that the present study has unfolded follow as well from the budget model. As some of our participating leaders mentioned, there is a risk that students in mainstream classes may ultimately pay the price of adopting the decentralised model. As observed in the results section, this is already happening in some schools. This clearly makes it necessary to ask (as some of our participants do) whether it is fair to construct such a system with its long-term consequences.

The shortcomings of the model can lead to the conclusion that municipalities should return to the centralised budget model. However, would this really be a solution? As the proponents state in some of the aforementioned quotes, there are, in fact, very strong rationales for the model and it seems to solve some of the problems of the classical centralised model that presumably all municipalities in Denmark had about 12 years back. Re-centralising the budget would draw back resources from the schools to the central municipal board. This would leave fewer resources at the school level and thus decrease the capacity to work for inclusion through, for instance, two teachers teaching the same class, co-teaching, or special support groups at school.

Do the findings of the present case study have direct relevance for school systems outside the Danish context that it investigates? The findings support the types of conclusions put forward by, for instance, Kwak [10], that the introduction of incentives in the budget model leads to a decrease in the fraction of students referred to special educational support. The case study adds to such conclusions by unfolding in further detail how this type of budget model works through the added economic pressure that the school leaders report. In this way, the present study investigates and unfolds some of the mechanisms underlying the aggregated effects that can be studied at the population level. Of course, direct comparisons between school systems that differ in many ways should always be performed with great caution and it is necessary to point out that further studies are needed in order to unfold in precise detail the mechanisms in the context studied by, for instance, Kwak.

The present case study shows that at the core of the effort to channelize extra resources to schools in order to develop an inclusive school system lies a difficult dilemma, seemingly buried in institutional processes and procedures. Furthermore, coming out of this dilemma does not seem easy. Hopefully, more research following school development in Denmark and internationally in the forthcoming years will be able to answer the question that the study opens. Is it possible to ensure that special educational budgets are available to school leaders (so that they can be invested in creating inclusive learning environments in mainstream schools) and, at the same time, avoid the risk of ending up in a situation where some students carry the cost of other student’s accommodations?

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Transcript symbols

| … | Pause |

| (…) | Some talk is left out |

| UPPER CASE | Loud or animated talk |

| [Comment] | Comments, e.g., gestures, short explanations |

References

- Salamanca Statement. The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000098427 (accessed on 7 November 2022).

- Danish Ministry of Finance; Danish Ministry of Education; Danish Association of Municipalities; Deloitte Business Consulting. Specialundervisning I Folkeskolen. Veje Til en Bedre Organisering og Styring [Special Educational Support in the Public School. Roads to Better Organisation and Steering]. 2010. Available online: https://www.ft.dk/samling/20091/almdel/udu/bilag/244/859480.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Tegtmejer, T.; Hjörne, E.; Säljö, R. ‘The ADHD diagnosis has been thrown out’: Exploring the dilemmas of diagnosing children in a school for all. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2019, 25, 671–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langager, S. Children and youth in behavioral and emotional difficulties, skyrocketing diagnosis and inclusion/exclusion processes in school tendencies in Denmark. Emot. Behav. Difficulties 2014, 19, 284–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindeberg, N.H.; Tegtmejer, T.; Iversen KAndreasen, A.G.; Ibsen, J.T.; Rangvid, B.S.; Bjørnholt, B.; Ruge, M.; Ellermann, K.G. Inkluderende Læringsmiljøer og Specialpædagogisk Bistand. Delrapport 2. Styring, Organisering og Faglig Praksis [Inclusive Learning Environments and Special Educational Support. Report No 2. Steering, Organisation and Professional Practice]; VIVE—Det Nationale Forsknings-og Analysecenter for Velfærd: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cullen, J.B. The impact of fiscal incentives on student disability rates. J. Public Econ. 2003, 87, 1557–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, J.P. Fixing special education. Peabody J. Educ. 2007, 82, 703–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, J.P.; Forster, G. Effects of Funding Incentives on Special Education Enrollment; The Manhattan Institute: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wishart, D.; Jahnukainen, M. Difficulties associated with the coding and categorization of students with emotional and behavioural disabilities in Alberta. Emot. Behav. Difficulties 2010, 15, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, S. The impact of intergovernmental incentives on student disability rates. Public Financ. Rev. 2010, 38, 41–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Index100 2020. Kommunernes Styring af Specialundervisningsområdet: Økonomimodeller, Visitation og Udgifter [Municipal Steering of the Area of Special Educational Support. Economic Models, Referral and Expenditures]. Social- og Indenrigsministeriets Benchmarkingenhed: Copenhagen, Denmark. Available online: https://simb.dk/media/37840/kommunernes-styring-af-specialundervisningsomraadet.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Kvale, S.; Brinkmann, S. Interview. Det Kvalitative Forskningsinterview Som Håndværk, 3. udg. [Interview. Qualitative Research Interview as Craftsmanship], 3rd ed.; Hans Reitzels Forlag: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- European General Data Protection Regulation (Regulation 679). Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the Protection of Natural Persons with Regard to the Processing of Personal Data and on the Free Movement of Such Data, and Repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation). 2016. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32016R0679&from=DA (accessed on 10 October 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).