Student Perceptions of Online Education during COVID-19 Lockdowns: Direct and Indirect Effects on Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Procedure

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data Analysis

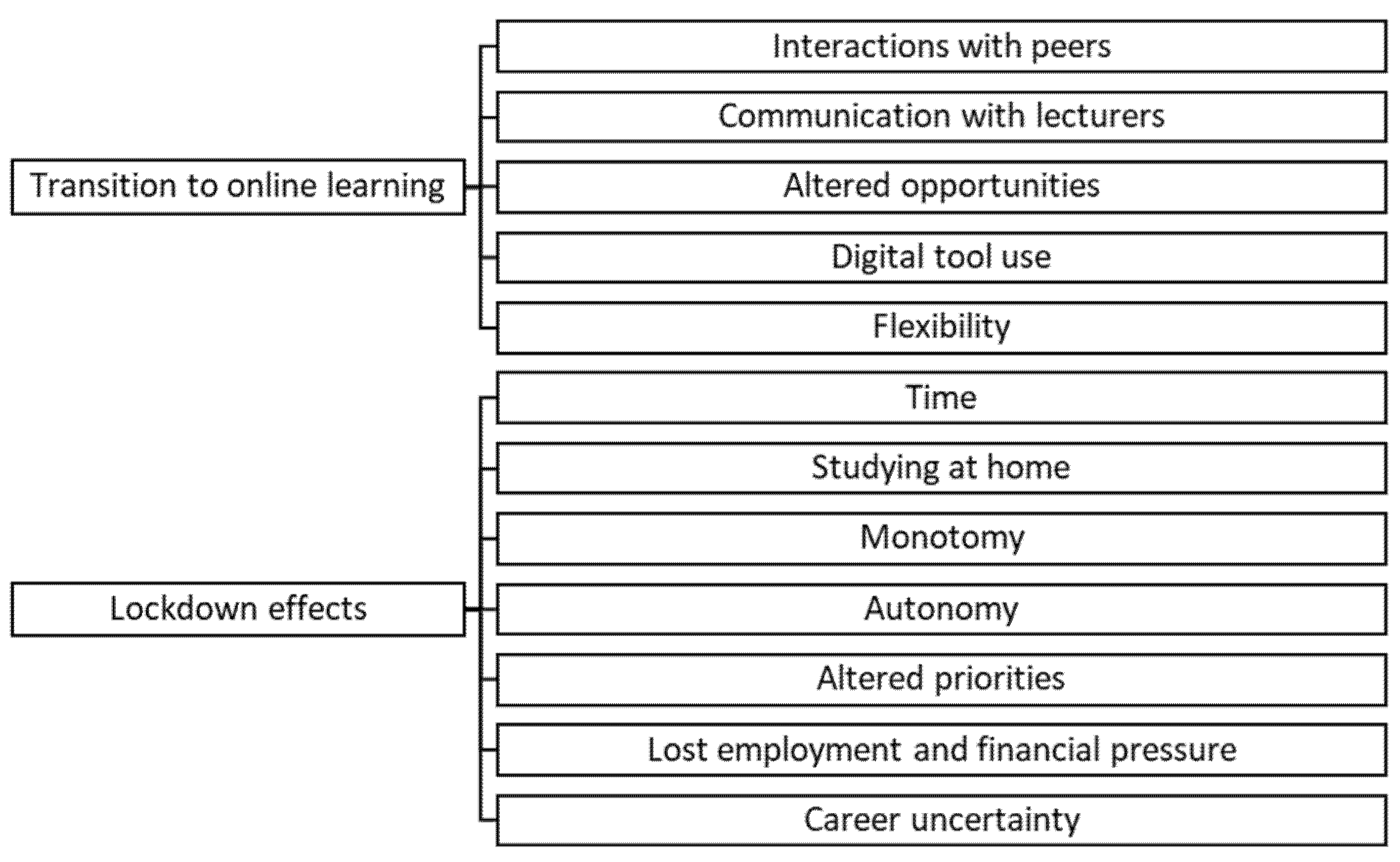

3. Results

3.1. Transition to Online Learning

3.1.1. Interaction with Peers

“Studying for me would usually involve leaving the house and using library facilities with my friends and housemates... When it was like this, I found studying enjoyable and felt that I got a lot done.” [Survey, Female, Undergraduate, Medical and Applied Health Sciences, Home]

“Not being able to [see] people’s reactions and their body language. That was quite difficult because I need the full expressions and the full body movements and language to be able to understand what someone means.” [Interview, Female, Postgraduate Taught, Natural Sciences and Maths, Home]

“The staff were unfamiliar with the format and there were a few technological errors. This meant that less time was spent teaching and more time sorting cams, mics, sharing slides etc.” [Interview, Male, Undergraduate, Social Sciences and Economics, Home]

3.1.2. Communication with Lecturers

“I think asking questions in a virtual environment is a lot easier than asking questions in a crowded lecture room, just in terms of understanding, and volume and things like that.” [Interview, Female, Undergraduate, Natural Sciences and Maths, Home]

“Normally you know when your lecturer’s office hours are, so you could always just pop in without warning whenever you like, but emailing people online, sometimes you’d have to wait a couple days for a response […] it is definitely less convenient than just being able to speak to someone face to face” [Interview, Female, Undergraduate, Arts and Humanities, Home]

3.1.3. Altered Opportunities

“Many of the events I would not normally have the ability to attend due to location are now online so I can call into a zoom hosted at Stanford then being limited to the London area.” [Survey, Female, Taught Postgraduate, Arts and Humanities, International]

“The resources I needed just did not exist online. They were only in libraries… it was kind of a last-minute scramble to like, ‘OK, so now I still need to reach a certain word count. You know, how do I do that with the material that I do have?’ And I think it ended up affecting my mark a bit.” [Interview, Female, Postgraduate Taught, Arts and Humanities, International]

3.1.4. Digital Tool Use

“[The online forum was] more successful because it doesn’t really deviate from past experiences. The less change there is, the easier it is for students to adapt.” [Female, Undergraduate, Medical and Applied Health Sciences, International]

“It saves me carrying a folder around, it’s all on my laptop—now that I’m comfortable with using it […] there’s no point in me kind of having a shelf full of notes, some books that I have that weigh a ton. Now that I forced myself to get used to it, I’m definitely going to keep using it.” [Interview, Male, Undergraduate, Arts and Humanities, Home]

“I think spending a lot of time just sat down in front of the screen is a bit of a disadvantage because, then you can’t switch off, or you know, even when you’re relaxing, you’re still watching TV or looking at some sort of screen.” [Interview, Female, Undergraduate, Natural Sciences and Maths, Home]

3.1.5. Flexibility

“I’ve found transcripts of the lecture and PowerPoints with corresponding audio very helpful. […] Generally having the freedom to complete tasks in our own time, rather than having to be at a lecture at a set time, has been very helpful and allowed me to work around difficulties at home.” [Female, Undergraduate, Arts and Humanities, Home]

“I don’t see the appeal of me going to lectures. That was often, not a waste of time, but it’s an hour to get there, an hour to come back, you know, I would always come early.” [Interview, Female, Postgraduate Taught, Social Sciences and Economics, EU]

3.2. Lockdown Effects

3.2.1. Time

“Everything was so confusing right then, I feel like I lost a lot of time just in stress and planning, and not being certain about the future.” [Interview, Female, Undergraduate, Natural Sciences and Maths, Home]

“[…] for preparation of some online lectures, there is often a reading list of things you should read. Before the lockdown maybe I read 60%. During the lockdown, maybe I read 90%.” [Male, Taught Postgraduate, Medical and Applied Health Sciences, Home]

3.2.2. Studying at Home

“I have to look after my 10-year-old sister that is at home all day. My mother has a fragile mental state and staying locked up at home is not helping at all […]. My dad is trying to continue running his business which has just lots of financial assets. So, it’s a slight turmoil at home at the moment.” [Survey, Female, Undergraduate, Natural Sciences and Maths, Home]

“I’m sharing a room with my younger sister. Her school also stopped, so we had to come up with some rules with studying times […]. I did not have a very comfortable place to study.” [Interview, Female, Undergraduate, Social Sciences and Economics, EU]

“It is more challenging to study in my room because my room was my place to rest, sleep, watch Netflix and relax, but now it’s everything in one.” [Interview, Female, Postgraduate Taught, Natural Sciences and Maths, International]

“I sent an email to the library at one point because […] some of us have been living on campus and don’t have like a common room or just anything. […] I was like “I would literally wear hazmat suit if you could just let me sit at a table somewhere, like it doesn’t have to be inside. Just give me a table.” [Interview, Female, Postgraduate Taught, Arts and Humanities, International]

3.2.3. Monotony

“I think it’s way easier to study all day when you have things to look forward to, […], when you have a life outside of studying.” [Interview, Female, Postgraduate Taught, Social Sciences and Economics, EU]

“[…] if I had access to like gym equipment or something like that whilst I was writing my thesis […], I feel like I could have maybe done even a bit better, or I would have stayed a little bit more sane and mentally stable. The gym was my main outlet.” [Interview, Female, Taught Postgraduate, Natural Sciences and Maths, Home]

“I would say, has just been so hard to make myself function every day and get out of bed. […] at first I was like cooking all kinds of stuff and then the more I’m just like ‘I’ve got to feed myself again. Like here we go’.” [Interview, Female, Postgraduate Taught, Arts and Humanities, International]

3.2.4. Autonomy

“In terms of like time management, everything is just endless […] I didn’t really realize it before, but it’s like I’d go to the library for two hours and then get lunch and things would kind of be broken up […] being at home… it just kind of feels endless, like I should be working on it every minute.” [Interview, Female, Postgraduate Taught, Arts and Humanities, International]

“I am able to manage my time appropriately, allowing me enough time for leisure and to help my family with grocery shopping.” [Survey, Female, Taught Postgraduate, Social Sciences and Economics, EU]

3.2.5. Altered Priorities

“I’m writing about cyberattacks and whatnot, it seems futile, a lot of it seems futile when there are so many deaths […] I think it feels really just like studying doesn’t matter as much.” [Interview, Female, Postgraduate Taught, Social Sciences and Economics, EU]

“My dad lost his job due to COVID-19. He was the sole income earner of our household. Now, I find myself sometimes desperately looking for jobs online during the time that I would have otherwise programmed for studying.” [Survey, Female, Undergraduate, Medical and Applied Health Sciences, EU]

“Since the outbreak my focus has been more family-orientated, spending quality time with them at home, helping out wherever possible and appreciating life. I still carry out all my assignments, lectures and readings, but they are no longer the sole focus of my time.” [Survey, Female, Undergraduate, Medical and Applied Health Sciences, Home]

3.2.6. Lost Employment and Financial Pressures

“Because I had no shifts, I couldn’t pay my rent and so I moved home. The flat I was renting is currently empty, but I still have to pay rent as I am tied into the contract and the management company won’t let me leave. I am having to borrow money to pay the rent.” [Survey, Male, Undergraduate, Medical and Applied Health Sciences, Home]

3.2.7. Career Uncertainty

“I am finished with my MA after I submit my dissertation in late August and many companies have a hiring freeze right now. I am also up against a lot more people looking for work due to the skyrocketing unemployment rate.” [Survey, Female, Taught Postgraduate, Arts and Humanities, International]

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Murphy, M.P. COVID-19 and emergency eLearning: Consequences of the securitization of higher education for post-pandemic pedagogy. Contemp. Secur. Policy 2020, 41, 492–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dommett, E.J.; Gardner, B.; van Tilburg, W. Staff and students perception of lecture capture. Internet High. Educ. 2020, 46, 100732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dommett, E.J. Understanding the use of online tools embedded within a virtual learning environment. Int. J. Virtual Pers. Learn. Environ. 2019, 9, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boelens, R.; Van Laer, S.; De Wever, B.; Elen, J. Blended Learning in Adult Education: Towards a Definition of Blended Learning. Adult Learners Online Project Report. 2015. Available online: https://biblio.ugent.be/publication/6905076/file/6905079 (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Bliuc, A.-M.; Goodyear, P.; Ellis, R.A. Research focus and methodological choices in studies into students’ experiences of blended learning in higher education. Internet High. Educ. 2007, 10, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneckenberg, D. Understanding the real barriers to technology-enhanced innovation in higher education. Educ. Res. 2009, 51, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dua, A.B.; Kilian, A.; Grainger, R.; Fantus, S.A.; Wallace, Z.S.; Buttgereit, F.; Jonas, B.L. Challenges, collaboration, and innovation in rheumatology education during the COVID-19 pandemic: Leveraging new ways to teach. Clin. Rheumatol. 2020, 39, 3535–3541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, L.; Gardner, B.; Dommett, E.J. The Post-Pandemic Lecture: Views from Academic Staff across the UK. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockwell, B.R.; Stockwell, M.S.; Cennamo, M.; Jiang, E. Blended Learning Improves Science Education. Cell 2015, 162, 933–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holley, D.; Dobson, C. Encouraging student engagement in a blended learning environment: The use of contemporary learning spaces. Learn. Media Technol. 2008, 33, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, G. Using blended learning to increase learner support and improve retention. Teach. High. Educ. 2007, 12, 349–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, T.; Bradley, C.; Chalk, P.; Jones, R.; Pickard, P. Using blended learning to improve student success rates in learning to program. J. Educ. Media 2003, 28, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Pérez, M.V.; Pérez-López, M.C.; Rodríguez-Ariza, L. Blended learning in higher education: Students’ perceptions and their relation to outcomes. Comput. Educ. 2011, 56, 818–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, N.; Lau, A.M.S. Blending learning: Widening participation in higher education. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2010, 47, 405–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wivell, J.; Day, S. Blended learning and teaching: Synergy in action. Adv. Soc. Work. Welf. Educ. 2015, 17, 86. [Google Scholar]

- Bowyer, J.; Chambers, L. Evaluating blended learning: Bringing the elements together. Res. Matters A Camb. Assess. Publ. 2017, 23, 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Rovai, A.P. In search of higher persistence rates in distance education online programs. Internet High. Educ. 2003, 6, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.M. Critical success factors for e-learning acceptance: Confirmatory factor models. Comput. Educ. 2007, 49, 396–413. [Google Scholar]

- Song, L.; Singleton, E.S.; Hill, J.R.; Koh, H.M. Improving online learning: Student perceptions of useful and challenging characteristics. Internet High. Educ. 2004, 7, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadad, W. ICT-in-Education Toolkit Reference Handbook; InfoDev: Lystrup, Denmark, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Marriott, N.; Marriott, P.; Selwyn, N. Accounting undergraduates’ changing use of ICT and their views on using the Internet in higher education—Aa research note. Account. Educ. 2004, 13, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielinski, D. The Lie of Online Learning. Training 2000, 37, 38–40. [Google Scholar]

- Willging, P.A.; Scott, J.D. Factors that influence students’ decision to dropout of online courses. J. Asynchronous Learn. Netw. 2009, 13, 115–127. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, F.A.; Nelson, E.; Delfino, K.; Han, H. A blended approach to learning in an obstetrics and gynecology residency program: Proof of concept. J. Med. Educ. Curric. Dev. 2015, 2, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pye, G.; Holt, D.; Salzman, S.; Bellucci, E.; Lombardi, L. Engaging diverse student audiences in contemporary blended learning environments in Australian higher business education: Implications for design and practice. Australas. J. Inf. Syst. 2015, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginns, P.; Ellis, R. Quality in blended learning: Exploring the relationships between on-line and face-to-face teaching and learning. Internet High. Educ. 2007, 10, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, H.-J.; Brush, T.A. Student perceptions of collaborative learning, social presence and satisfaction in a blended learning environment: Relationships and critical factors. Comput. Educ. 2008, 51, 318–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lister, K.; Seale, J.; Douce, C. Mental health in distance learning: A taxonomy of barriers and enablers to student mental wellbeing. Open Learn. J. Open Distance E-Learn. 2021, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Means, B.; Neisler, J. Teaching and learning in the time of COVID: The student perspective. Online Learn. 2021, 25, 8–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Salman, S.; Haider, A.S. Jordanian University Students’ Views on Emergency Online Learning during COVID-19. Online Learn. 2021, 25, 286–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsoufi, A.; Alsuyihili, A.; Msherghi, A.; Elhadi, A.; Atiyah, H.; Ashini, A.; Ashwieb, A.; Ghula, M.; Ben Hasan, H.; Abudabuos, S. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical education: Medical students’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding electronic learning. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0242905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, L.R.; Tanti, I.; Maharani, D.A.; Wimardhani, Y.S.; Julia, V.; Sulijaya, B.; Puspitawati, R. Student perspective of classroom and distance learning during COVID-19 pandemic in the undergraduate dental study program Universitas Indonesia. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conklin, S.; Dikkers, A.G. Instructor social presence and connectedness in a quick shift from face-to-face to online instruction. Online Learn. 2021, 25, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinu, L.M.; Byrom, N.C.; Mehta, K.J.; Everett, S.; Foster, J.L.; Dommett, E.J. Predicting student mental wellbeing and loneliness and the importance of digital skills. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2022, 46, 1040–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dost, S.; Hossain, A.; Shehab, M.; Abdelwahed, A.; Al-Nusair, L. Perceptions of medical students towards online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic: A national cross-sectional survey of 2721 UK medical students. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e042378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motz, B.A.; Quick, J.D.; Wernert, J.A.; Miles, T.A. A pandemic of busywork: Increased online coursework following the transition to remote instruction is associated with reduced academic achievement. Online Learn. 2021, 25, 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, E.; Capps, N.; Ward, N.; McCormack, L.; Staley, J. Maintaining Academic Performance and Student Satisfaction during the Remote Transition of a Nursing Obstetrics Course to Online Instruction. Online Learn. 2021, 25, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlenz, M.A.; Schmidt, A.; Wöstmann, B.; Krämer, N.; Schulz-Weidner, N. Students’ and lecturers’ perspective on the implementation of online learning in dental education due to SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19): A cross-sectional study. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, R.; Mansour, A.E.; Fadda, W.A.; Almisnid, K.; Aldamegh, M.; Al-Nafeesah, A.; Alkhalifah, A.; Al-Wutayd, O. The sudden transition to synchronized online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia: A qualitative study exploring medical students’ perspectives. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpungose, C.B. Emergent transition from face-to-face to online learning in a South African University in the context of the Coronavirus pandemic. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2020, 7, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, T.E.; Lee, S.Y. College students’ experience of emergency remote teaching due to COVID-19. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 119, 105578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, V.; Braun, V. Teaching thematic analysis: Overcoming challenges and developing strategies for effective learning. Psychologist 2013, 26, 120–123. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mays, N.; Pope, C. Rigour and qualitative research. BMJ Br. Med. J. 1995, 311, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bali, S.; Liu, M. Students’ Perceptions toward Online Learning and Face-to-Face Learning Courses. In Proceedings of the Journal of Physics: Conference Series, Surabaya, Indonesia, 21 July 2018; p. 012094. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, D.L. Virtual conferences democratize access to science. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarabipour, S. Research Culture: Virtual conferences raise standards for accessibility and interactions. eLife 2020, 9, e62668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Counsell, C.W.; Elmer, F.; Lang, J.C. Shifting away from the business-as-usual approach to research conferences. Biol. Open 2020, 9, bio056705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margaryan, A.; Littlejohn, A.; Vojt, G. Are digital natives a myth or reality? University students’ use of digital technologies. Comput. Educ. 2011, 56, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartzman, R. Refining the question: How can online instruction maximize opportunities for all students? Commun. Educ. 2007, 56, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ward, M.; Newlands, D. Use of the Web in undergraduate teaching. Comput. Educ. 1998, 31, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, M.R.; Clinton, M.E. A study exploring the impact of lecture capture availability and lecture capture usage on student attendance and attainment. High. Educ. 2019, 77, 403–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Steenbergen, E.F.; Ybema, J.F.; Lapierre, L.M. Boundary management in action: A diary study of students’ school-home conflict. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2018, 25, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Noguera, M.D.; Hervás-Gómez, C.; De la Calle-Cabrera, A.M.; López-Meneses, E. Autonomy, Motivation, and Digital Pedagogy Are Key Factors in the Perceptions of Spanish Higher-Education Students toward Online Learning during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eneau, J.; Develotte, C. Working together online to enhance learner autonomy: Analysis of learners’ perceptions of their online learning experience. ReCALL 2012, 24, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Martin, F.; Budhrani, K.; Ritzhaupt, A. Award-Winning Faculty Online Teaching Practices: Elements of Award-Winning Courses. Online Learn. 2019, 23, 160–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowenthal, P.; Dunlap, J.; Snelson, C. Live synchronous web meetings in asynchronous online courses: Reconceptualizing virtual office hours. Online Learn. J. 2017, 21, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachopoulos, D.; Makri, A. Online communication and interaction in distance higher education: A framework study of good practice. Int. Rev. Educ. 2019, 65, 605–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erten, P.; Ozdemir, O. The Digital Burnout Scale. İnönü Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi Derg. 2020, 21, 668–683. [Google Scholar]

- Bozkurt, A.; Sharma, R.C. Education in normal, new normal, and next normal: Observations from the past, insights from the present and projections for the future. Asian J. Distance Educ. 2020, 15, i-x. [Google Scholar]

- Dommett, E.J. Optimizing the University Experience Through Digital Skills Training: Beyond Digital Nativity. In The Future of Online Education: Advancements in Learning and Instruction; McKenzie, S.P., Arulkadacham, L., Chung, J., Aziz, Z., Eds.; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, R.; Evans, B.; Li, Q.; Cung, B. Does inducing students to schedule lecture watching in online classes improve their academic performance? An experimental analysis of a time management intervention. Res. High. Educ. 2019, 60, 521–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waleska, H.; McNichols, C.; Zachar, S.; Wright, T.; Cauthen, J.; Konu, S.; DeDomenico, M.; Bailey, R. Lost in Space: A Case Study on Optimizing Student Spaces at the University of Virginia. In Proceedings of the 2019 Systems and Information Engineering Design Symposium (SIEDS), Charlottesville, VA, USA, 26–26 April 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Fleischmann, K. Hands-on versus virtual: Reshaping the design classroom with blended learning. Arts Humanit. High. Educ. 2021, 20, 87–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Data | University Population | Survey 1 (n = 417) | Survey 2 (n = 235) | Interviews (n = 14) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female:male | 1.76 | 4.63 | 4.48 | 1.8 |

| White:BAME | 1.25 1 | 1.80 | 1.77 | 1.33 |

| Home:EU | 4.85 | 2.03 | 2.34 | 4.5 |

| Home:international | 2.52 | 2.57 | 2.73 | 3 |

| Aged under 20 | 38% | 34% | 34% | 7% |

| Aged 21–24 | 35% | 49% | 50% | 64% |

| Aged over 25 | 33% | 18% | 16% | 29% |

| Undergraduate:postgraduate | 1.77 | 2.41 | 2.36 | 1 |

| Level of Study | Faculty | Fee Status | Gender | Age | Ethnicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Undergraduate | Arts & Humanities | Home | Female | 21–25 | White British |

| Home | Male | 21–25 | White British | ||

| Home | Male | 21–25 | Indian | ||

| Natural Sciences & Maths | Home | Female | 21–25 | Indian | |

| Home | Female | 21–25 | Mixed ethnicity | ||

| Home | Male | 18–20 | White British | ||

| Social Sciences & Economics | EU | Female | 21–25 | White non-British | |

| Postgraduate taught | Arts & Humanities | Home | Female | Over 40 | Caribbean |

| International | Female | 21–25 | White non-British | ||

| Medical & Applied Health Sciences | Home | Male | Over 40 | White British | |

| International | Female | 26–30 | Other ethnic group | ||

| Natural Sciences & Maths | Home | Female | 21–25 | Indian | |

| Social Sciences & Economics | EU | Female | 21–25 | White non-British | |

| International | Male | Over 40 | White British |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dinu, L.M.; Baykoca, A.; Dommett, E.J.; Mehta, K.J.; Everett, S.; Foster, J.L.H.; Byrom, N.C. Student Perceptions of Online Education during COVID-19 Lockdowns: Direct and Indirect Effects on Learning. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 813. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12110813

Dinu LM, Baykoca A, Dommett EJ, Mehta KJ, Everett S, Foster JLH, Byrom NC. Student Perceptions of Online Education during COVID-19 Lockdowns: Direct and Indirect Effects on Learning. Education Sciences. 2022; 12(11):813. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12110813

Chicago/Turabian StyleDinu, Larisa M., Ardic Baykoca, Eleanor J. Dommett, Kosha J. Mehta, Sally Everett, Juliet L. H. Foster, and Nicola C. Byrom. 2022. "Student Perceptions of Online Education during COVID-19 Lockdowns: Direct and Indirect Effects on Learning" Education Sciences 12, no. 11: 813. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12110813

APA StyleDinu, L. M., Baykoca, A., Dommett, E. J., Mehta, K. J., Everett, S., Foster, J. L. H., & Byrom, N. C. (2022). Student Perceptions of Online Education during COVID-19 Lockdowns: Direct and Indirect Effects on Learning. Education Sciences, 12(11), 813. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12110813