How Do Prospective Teachers Address Pupils’ Ideas during School Practices?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. The Nature of Ideas in Science Education

2.2. The Utilisation of Ideas in the Teaching of Science

2.3. The Change of Pupils’ Ideas for Learning Science

2.4. Consideration of Pupils’ Ideas in Teaching Practices

2.5. Aims of the Study

- What conceptions of pupils’ ideas do prospective teachers have?

- How do prospective teachers integrate pupils’ ideas when they teach science?

- What coherence exists between both?

3. Methods

- The nature of pupils’ ideas, on which the prospective teachers’ planning of the teaching of the scientific content is based.

- The utilisation of pupils’ ideas, as proposed in the sequence of activities.

- The change in ideas, on which the assessment process of the prospective teachers during the T/L process is based.

3.1. Participants

3.2. Data Collection

3.2.1. Questionnaire on Conceptions

3.2.2. School Practices Report

- Planning the educational proposal. In this block, prospective teachers were asked to carry out an analysis of the contents from a didactic point of view, in which the PT identified the most frequent pupils’ ideas, their origin (social, analogical, etc.), and their role in the T/L process. It makes it possible to determine their conceptions of the nature of ideas.

- Design of the sequence of activities and methodology. Here, prospective teachers were asked to specify, for each activity, (1) the teaching and learning objectives; (2) the teaching contents; (3) the material and management; and (4) the tasks of the pupils and the teachers’ role. Thus, it allows us to establish how the ideas are utilised throughout the T/L process.

- Evaluation. In this block, prospective teachers were asked to show the assessment instruments and their reflections on pupils’ learning. It makes it possible to identify what considerations are made about the change in ideas.

3.3. Data Treatment

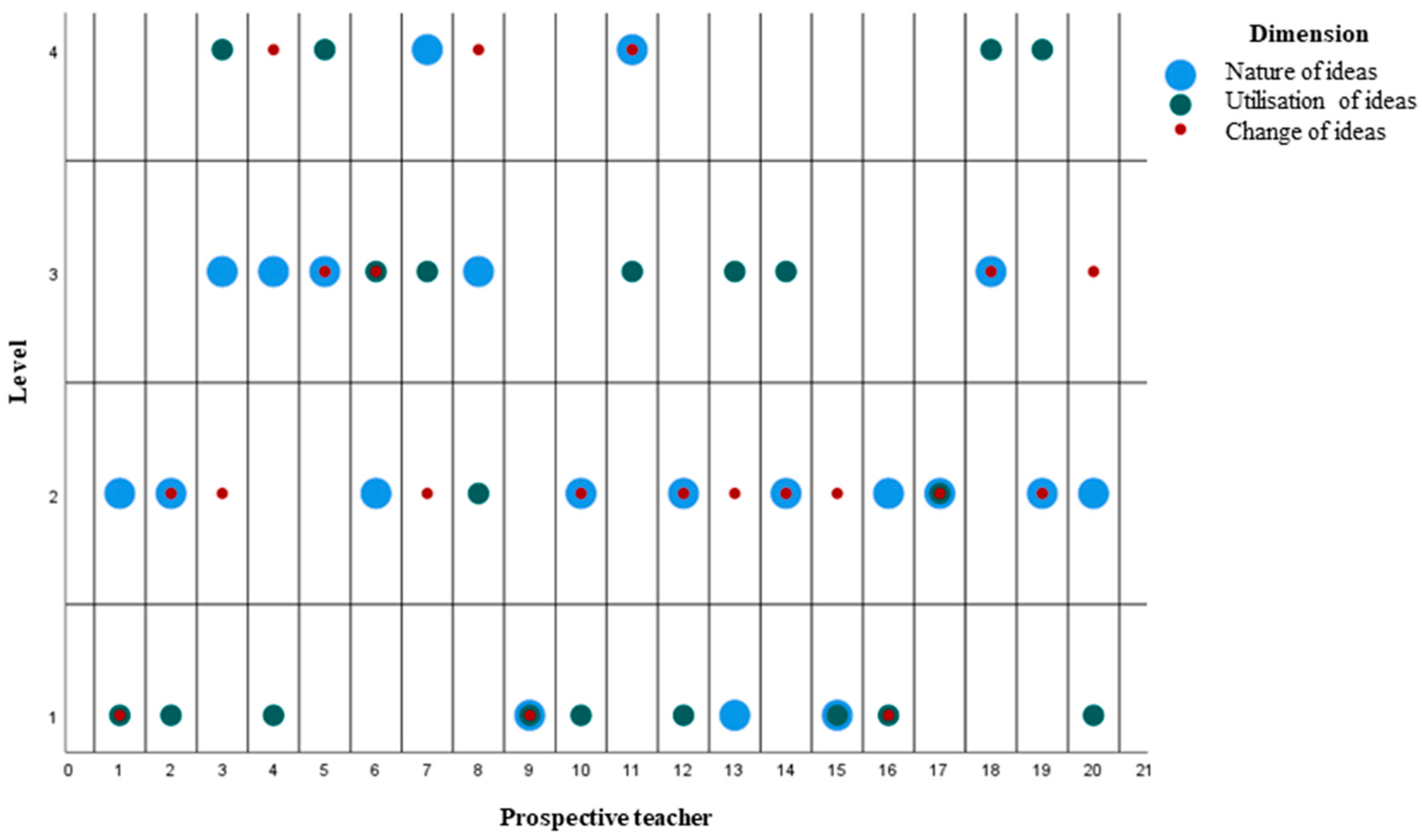

- To establish these levels as definitive, the units of information were reviewed and contrasted in several cycles of analysis, individually by two of the researchers involved, with 72% agreement. In order to resolve discrepancies, the three researchers contrasted them, obtaining 88% agreement in the coding, a value considered acceptable in the qualitative content analysis [66]. Thus, four definitive levels were established, and their frequencies were calculated. A higher level represents a PCK in which pupils’ ideas are considered alternative constructs to scientific knowledge, which must be utilised throughout the T/L process to facilitate change by reconstruction [16,18]. These levels were as follows:

- Level 1 was assigned to the educational proposals with a clearly traditional orientation, which conformed to the transmissive items proposed in the questionnaire. Regarding the nature of the ideas, at this level, PT considered pupils’ ideas as erroneous constructs, the result of bad learning, and not very useful for teaching. The ideas are used by the teacher to determine the initial level of knowledge. In terms of change, emphasis is placed on pupils remembering definitions and scientific terms.

- Level 2 was assigned to the educational proposals in which PT do not meet some of the transmission items, without fulfilling any of the items of the idea construction orientations. Regarding the nature of the ideas, at this level, the ideas are limited to previous academic knowledge, and are recognised as relevant to the T/L process. In addition, the ideas are used at the beginning of the topic to identify the starting level of the students and their interest in the subject. The aim is to replace these ideas with scientifically correct knowledge, which can be applied in new situations.

- Level 3 was assigned to the educational proposals that do not meet some of the transmission items, but they do comply with some of the construction of ideas orientation. At this level, the spontaneous nature of pupils’ ideas is recognised at this level. In relation to utilisation, ideas are used at different moments of intervention, especially at the beginning and end of the topic. Finally, the re-elaboration of ideas is facilitated, providing opportunities for pupils to assess the validity of their initial ideas.

- Level 4 was assigned to the educational proposals that expressly complied with the two items of the construction of ideas orientation in the questionnaire. In terms of nature, at this level, it is recognised that ideas constitute knowledge other than scientific knowledge, as a result of experiences, interests, and social interactions, from which students explain certain scientific phenomena. With regard to utilisation, the teacher pays attention to the use of ideas throughout the sequence, in order to facilitate their re-elaboration and also to detect the need for changes in the initial planning. Finally, the re-elaboration of ideas is encouraged, and the process of T/L is reviewed, assessing the reasons that may have led to learning that was different from what was planned.

4. Results

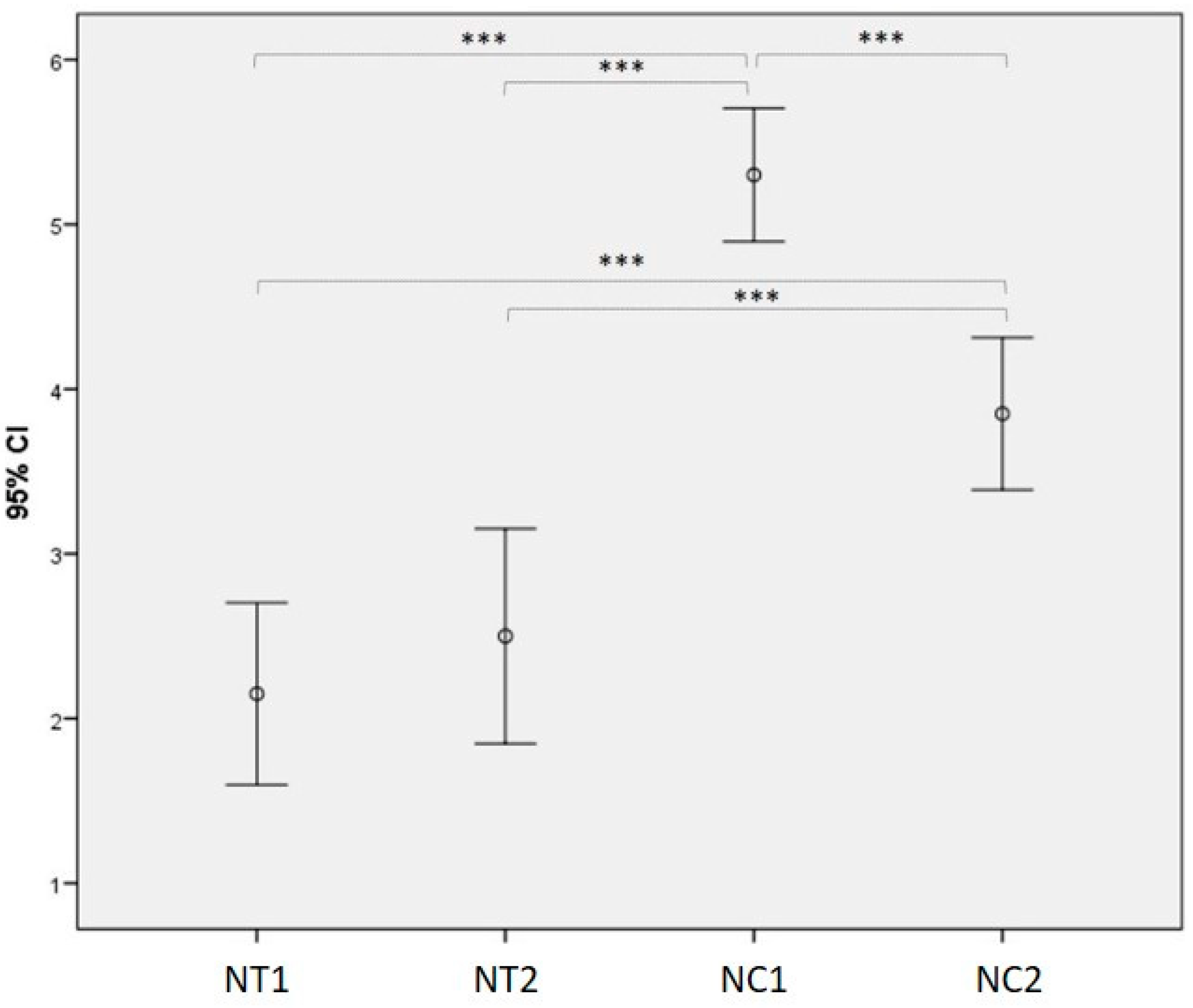

4.1. Prospective Teachers and the Nature of Pupils’ Ideas in Science Education

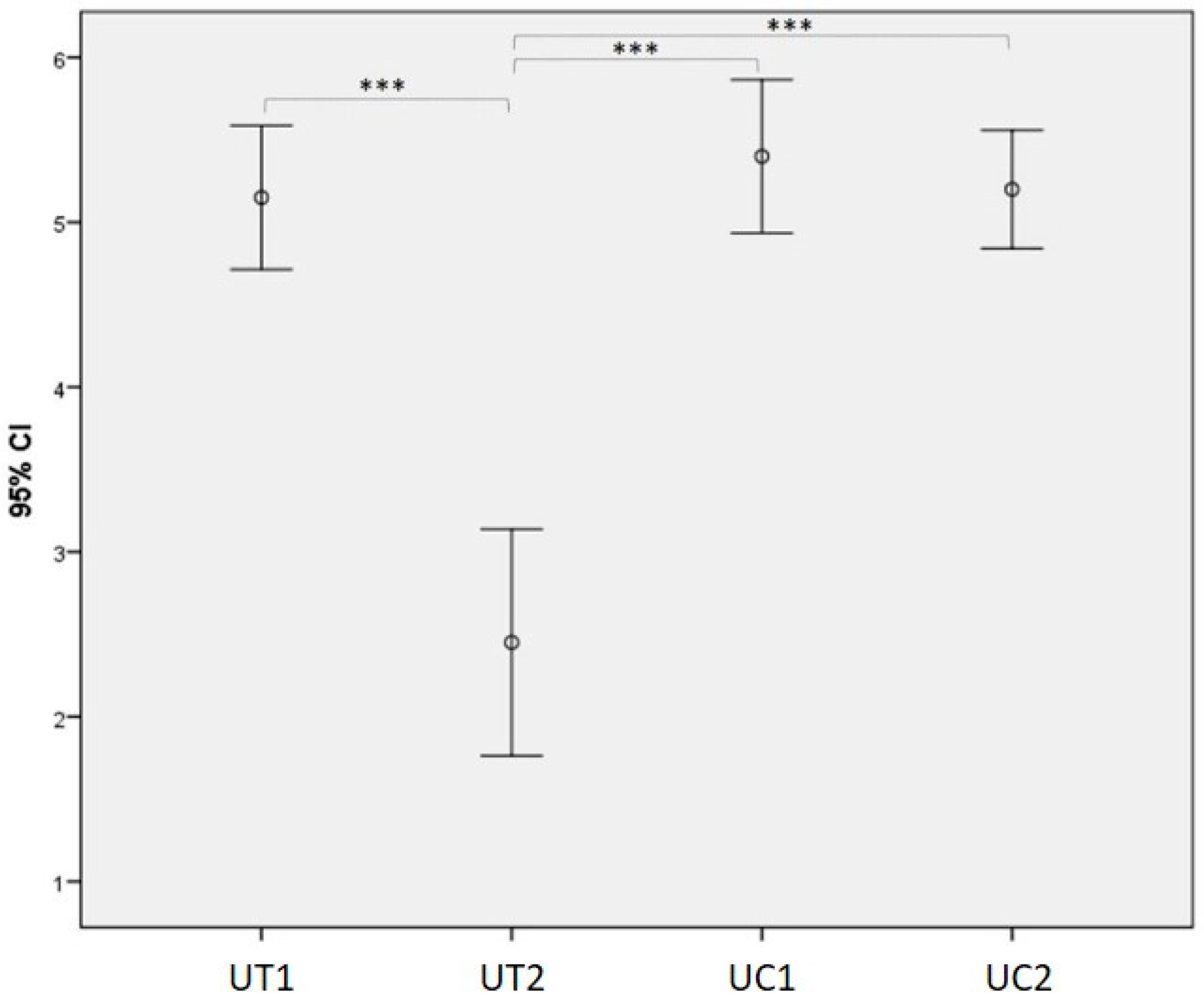

4.2. Prospective Teachers and the Utilisation of Pupils’ Ideas in Science Education

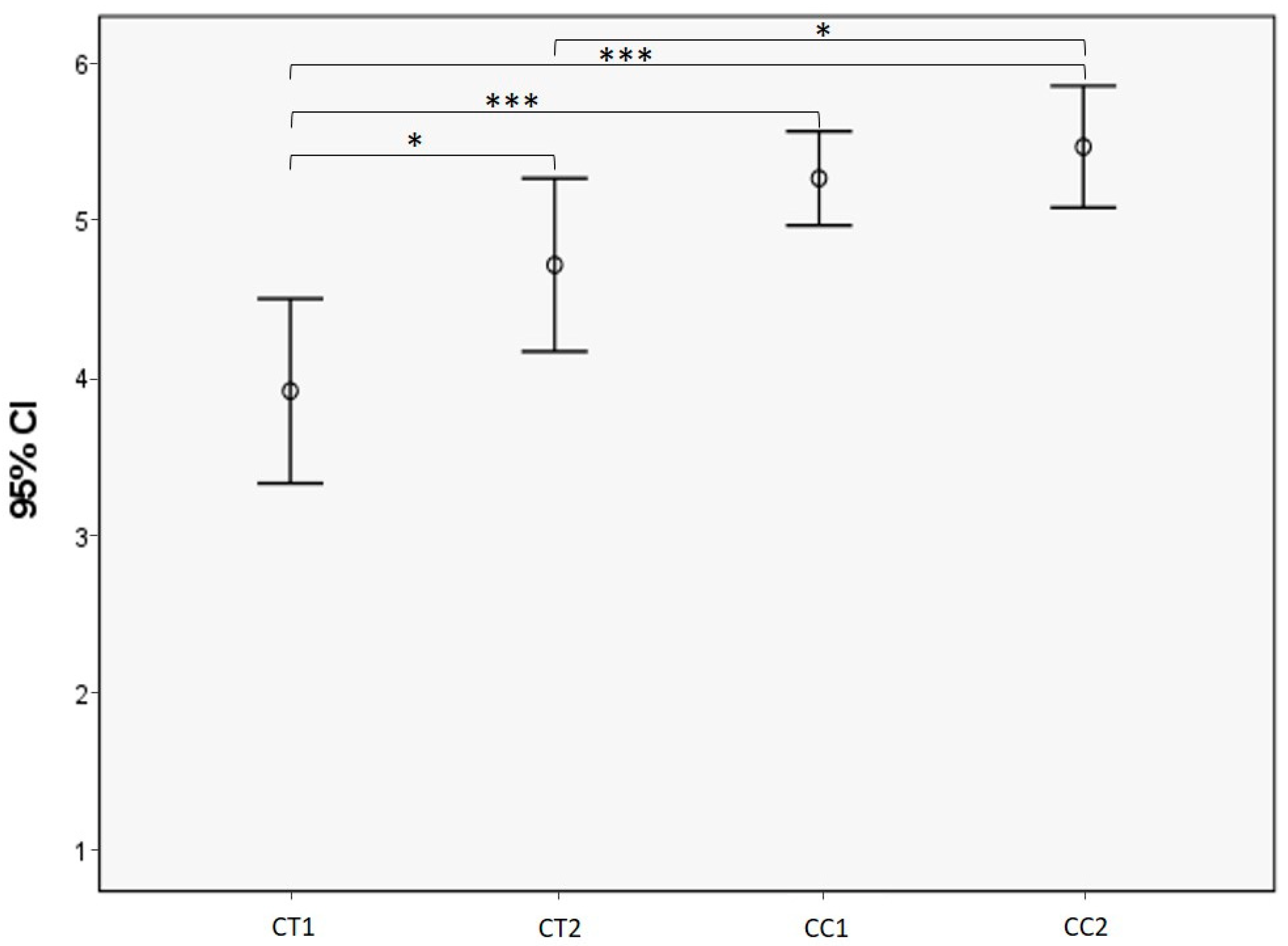

4.3. Prospective Teachers and the Change of Pupils’ Ideas in Science Education

4.4. Correlations Statistics

4.4.1. Correlations within Prospective Teachers’ Conceptions

4.4.2. Correlations When Prospective Teachers Integrate Pupils’ Ideas in Educational Proposals

4.4.3. Correlations between Conceptions and Integration of Students’ Ideas

5. Discussion

5.1. Prospective Teachers’ Conceptions about the Nature, Utilisation, and Change of Pupils’ Ideas in Science Education

5.2. Prospective Teachers’ Orientation When Addressing Pupils’ Ideas during School Practices

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gess-Newsome, J. A Model of Teacher Professional Knowledge and Skill Including PCK: Results of the Thinking from the PCK Summit. In Re-Examining Pedagogical Content Knowledge in Science Education, 1st ed.; Berry, A., Friedrichsen, P., Loughran, J., Eds.; Routledge Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 28–42. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson, P. Teaching for Understanding: The Complex Nature of Pedagogical Content Knowledge in Pre-service Education. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2008, 30, 1281–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamed, S.; Ezquerra, A.; Porlán, R.; Rivero, A. Exploring pre-service primary teachers’ progression towards inquiry-based science learning. Educ. Res. 2020, 62, 357–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnusson, S.; Krajcik, J.; Borko, H. Nature, sources and development of pedagogical content knowledge for science teaching. In Examining Pedagogical Content Knowledge; Gess-Newsome, J., Lederman, N.G., Eds.; Kluwer: Alphen aan den Rijn, The Netherlands, 1999; pp. 95–132. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.; Oliver, J.S. National Board Certification (NBC) as a catalyst for teachers’ learning about teaching: The effects of the NBC process on candidate teachers’ PCK development. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2008, 45, 812–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughran, J.; Mulhall, P.; Berry, A. Exploring Pedagogical Content Knowledge in Science Teacher Education. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2008, 10, 1301–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, R.M.; Plasman, K. Science teacher learning progressions: A review of science teacher’ pedagogical content Knowledge development. Rev. Educ. Res. 2011, 81, 530–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöberg, M.; Nyberg, E. Professional Knowledge for Teaching in Student Teachers’ Conversations about Field Experiences. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 2020, 31, 226–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierno, S.P.; Solbes, J.; Gavidia, V.; Tuzón, P. La formación científica y didáctica en el grado de maestro en Educación Primaria y la presencia de la indagación según el profesorado. Rev. Interuniv. Form. Profr. 2022, 97, 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driver, R. Students’ conceptions and the learning of science. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 1989, 11, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treagust, D.F.; Duit, R. Conceptual change: A discussion of theoretical, methodological and practical challenges for science education. Cult. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2008, 3, 297–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, J.A.; Lederman, N.G. Science teachers’ diagnosis and understanding of students’ preconceptions. Sci. Educ. 2003, 87, 849–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabel, J.L.; Forbes, C.T.; Flynn, L. Elementary teachers’ use of content knowledge to evaluate students’ thinking in the life sciences. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2016, 38, 1077–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solís, E.; Porlán, R.; del Pozo, R.M.; Harres, J. Aprender a detectar las ideas del alumnado de Primaria sobre los contenidos escolares de ciencias [Learn to detect the ideas of primary school students about school science content]. Investig. Esc. 2016, 88, 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haefner, L.A.; Zembal-Saul, C. Learning by doing? Prospective elementary teachers’ developing understandings of scientific inquiry and science teaching and learning. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2004, 26, 1653–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Pozo, R.M.; Rivero, A.; Azcárate, P. Las concepciones de los futuros maestros sobre la naturaleza, cambio y utilización didáctica de las ideas de los alumnos [The conceptions of the future teachers about the nature, change and didactic use of the ideas of the students]. Rev. Eureka Enseñ. Divulg. Cienc. 2014, 11, 348–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windschitl, M.; Thompson, J.; Braaten, M.; Stroupe, D. Proposing a core set of instructional practices and tools for teachers of science. Sci. Educ. 2012, 96, 878–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, D. Misconceptions about “misconceptions”: Preservice secondary science teachers’ views on the value and role of student ideas. Sci. Educ. 2012, 96, 927–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, D. Planning for the Elicitation of Students’ Ideas: A Lesson Study Approach With Preservice Science Teachers. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 2017, 28, 425–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, M. Misconceptions in Primary Science, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: London, UK, 2019; p. 275. [Google Scholar]

- Duit, R. Bibliography: Students’ and Teachers’ Conceptions and Science Education (STCSE). Available online: http://www.ipn.uni-kiel.de/aktuell/stcse/stcse.html (accessed on 5 September 2022).

- Francek, M. A Compilation and Review of over 500 Geoscience Misconceptions. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2013, 35, 31–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, H.O.; Cigdemoglu, C.; Moseley, C. A three-tier diagnostic test to assess pre-service teachers’ misconceptions about global warming, greenhouse effect, ozone layer depletion, and acid rain. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2012, 34, 1667–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Härmälä-Braskén, A.S.; Hemmi, K.; Kurtén, B. Misconceptions in chemistry among Finnish prospective primary school teachers—A long-term study. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2020, 42, 1447–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.R.; Zeichner, K.M. Idea and action: Action research and the development of conceptual change teaching of science. Sci. Educ. 1999, 83, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lijnse, P. Didactical structures as an outcome of research on teaching–learning sequences? Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2004, 26, 537–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, M.J. What Does it Mean to Notice my Students’ Ideas in Science Today?: An Investigation of Elementary Teachers’ Practice of Noticing their Students’ Thinking in Science. Cogn. Instr. 2018, 36, 297–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, D.M.; Hammer, D.; Coffey, J.E. Novice teachers’ attention to student thinking. J. Teach. Educ. 2009, 60, 142–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rönnebeck, S.; Bernholt, S.; Ropohl, M. Searching for a common ground—A literature review of empirical research on scientific inquiry activities. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2016, 52, 161–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LOMLOE. Ley Orgánica 3/2020, de 29 de Diciembre, por La Que se Modifica la Ley Orgánica 2/2006, de 3 de Mayo, de Educación. Available online: https://www.boe.es/diario_boe/txt.php?id=BOE-A-2020-17264 (accessed on 19 October 2022).

- Hamed, S.; Rivero, A. What do prospective teachers know about the sort of activities that are helpful in learning science? A progression of learning during a science methods course. Educ. Stud. 2022, 48, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porlán, R. Didáctica de las ciencias con conciencia [Science education with a conscience]. Enseñ. Cienc. 2018, 36, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnhart, T.; van Es, E. Studying teacher noticing: Examining the relationship among pre-service science teachers’ ability to attend, analyze and respond to student thinking. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2015, 45, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, S. El modelo constructivista con las nuevas tecnologías: Aplicado en el proceso de aprendizaje. Rev. Univ. Soc. Conoc. 2008, 5, 26–35. [Google Scholar]

- Jonassen, D.H. Evaluating Constructivistic Learning. Educ. Technol. 1991, 31, 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Godino, J.D.; Burgos, M. Interweaving Transmission and Inquiry in Mathematics and Sciences Instruction. In Education and Technology in Sciences; Villalba-Condori, K., Aduríz-Bravo, A., Lavonen, J., Wong, L.H., Wang, T.H., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, J.; Wilcox, J.; Easter, J. Learning to Learn: Drawing Students’ Attention to Ideas about Learning. Clgh. J. Educ. Strat. Issues Ideas 2022, 95, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duit, R. Students’ conceptual frameworks consequences for learning science. In The Psychology of Learning Science; Glynn, S., Yeany, R., Britton, B., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1991; pp. 65–85. [Google Scholar]

- Darling-Hammond, L.; Flook, L.; Cook-Harvey, C.; Barron, B.; Osher, D. Implications for educational practice of the science of learning and development. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2020, 24, 97–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wee, B. A Cross-cultural Exploration of Children’s Everyday Ideas: Implications for science teaching and learning. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2012, 34, 609–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, M.B.; Mateos, M.; Vilanova, S.L. Contenido y naturaleza de las concepciones de profesores universitarios de biología sobre el conocimiento científico. Rev. Electron. Enseñ. Cienc. 2011, 10, 23–39. [Google Scholar]

- Escrivá, I.; Rivero, A. Cambio de las concepciones del futuro profesorado de primaria acerca de las ideas de los alumnos [Changing conceptions of prospective elementary school teachers about students’ ideas]. Profr. Rev. Curric. Form. Profr. 2018, 22, 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, C.; Devine, A.; Tavares, J.T. Supporting conceptual change in school science: A possible role for tacit understanding. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2013, 35, 864–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Pozo, R.M.; de Juanas, A. La valoración de los maestros sobre la utilización didáctica de las ideas de los alumnos [Teachers’ assessment of the didactic use of students’ ideas]. Rev. Complut. Educ. 2013, 24, 267–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosebery, A.S.; Warren, B.; Tucker-Raymond, E. Developing interpretive power in science teaching. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2016, 53, 1571–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamayo, L.A. Tendencias de la pedagogía en Colombia [Pedagological trends in Colombia]. Rev. Latinoam. Estud. Educ. 2007, 3, 65–76. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=134112603005 (accessed on 30 July 2022).

- Gómez, A. Las concepciones alternativas, el cambio conceptual y los modelos explicativos del alumnado. In Áreas y Estrategias de Investigación en la Didáctica de las Ciencias Experimentales. Colección Formación en Investigación para Profesores; Merino, C., Gómez, A., Adúriz, A., Eds.; Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Servei de Publicacions: Barcelona, Spain, 2008; Volume 1, pp. 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Buck, G.A.; Trauth-Nare, A.; Kaftan, J. Making formative assessment discernable to preservice teachers of science. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2010, 47, 402–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delord, G.C.C.; Porlán, R. Del discurso tradicional al modelo innovador en enseñanza de las ciencias: Obstáculos para el cambio [From traditional discourse to innovative model in science education: Obstacles to change]. Didact. Cienc. Exp. Soc. 2018, 35, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamed, S.; Rivero, A. Conocimiento de los futuros maestros acerca de la enseñanza y aprendizaje de las ciencias. In Conocimiento Profesional del Profesor de Ciencias de Primaria y Conocimiento Escolar; Martínez, C.A., Valbuena, E.O., Eds.; Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas: Bogotá, Colombia, 2013; pp. 113–141. [Google Scholar]

- Rivero, A.; del Pozo, R.M.; Solís, E.; Azcárate, P.; Porlán, R. Cambio del conocimiento sobre la enseñanza de las ciencias de futuros maestros [Change in science education knowledge of prospective teachers]. Enseñ. Cienc. 2017, 35, 29–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ausubel, D.P.; Novak, J.D.; Hanesian, H. Psicología Educativa: Un Punto de Vista Cognitivo, 2nd ed.; Trillas: Mexico City, México, 1983; p. 626. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, M.; Fumagalli, L. Enseñar Ciencia Naturales. Reflexiones y Propuestas Didácticas, 1st ed.; Paidós Ibérica: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2000; p. 270. [Google Scholar]

- Azcárate, P.; Hamed, S.; del Pozo, R.M. Recurso formativo para aprender a enseñar ciencias por investigación escolar [Formative resource for learning how to teach science through scholarly research]. Investig. Esc. 2013, 80, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, J.; Jung, K.; Robinson, B.; Tretter, T.R. Teacher-developed Multi-Dimensional Science Assessments Supporting Elementary Teacher Learning about the Next Generation Science Standards. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 2022, 33, 55–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, C.; Sabel, J.L.; Zangori, L. Integrating life science content and instructional methods in elementary teacher education. Am. Biol. Teach. 2015, 77, 651–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabel, J.L.; Forbes, C.T.; Zangori, L. Promoting Prospective Elementary Teachers’ Learning to Use Formative Assessment for Life Science Instruction. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 2015, 26, 419–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, J.; Wilcox, J.; Patel, N.; Borzo, S.; Seebach, C.; Henning, J. The Power of Practicum Support: A Quasi-experimental Investigation of Elementary Preservice Teachers’ Science Instruction in A Highly Supported Field Experience. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 2022, 33, 392–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Driel, J.H.; Berry, A. Teacher Professional Development Focusing on Pedagogical Content Knowledge. Educ. Res. 2012, 41, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bueno, A.P.; de Chereguini, C.P.; Doménech, J.C. Cinco Problemas En La formación De Maestros Y Maestras Para enseñar Ciencias En Educación Primaria [Five Problems In The Training Of Teachers To Teach Science In Primary Education]. Rev. Interuniv. Form. Profr. 2022, 97, 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lederman, N.; Gess-Newsome, J. Reconceptualizing secondary science teacher education. In Examining Pedagogical Content Knowledge; Gess-Newsome, J., Lederman, N., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1999; Volume 6, pp. 199–213. [Google Scholar]

- Menon, D.; Azam, S. Preservice Elementary Teachers’ Identity Development in Learning to Teach Science: A Multi-site Case Study. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 2021, 32, 558–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrón, C. Concepciones epistemológicas y práctica docente. Una revisión [Epistemological conceptions and teaching practice. A review]. Rev. Docen. Univers. 2015, 13, 35–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valverde, M.; Esteve, P. Docentes en formación inicial: Concepciones acerca de la enseñanza y aprendizaje de las ciencias en el contexto de las prácticas escolares. In Investigación Educativa ente los Actuales Retos Migratorios; Romero, J.M., Cáceres, M.P., de la Cruz, J.C., Ramos, M., Eds.; Dykinson: Madrid, Spain, 2022; pp. 1289–1301. [Google Scholar]

- Schreier, M. Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2012; p. 272. [Google Scholar]

- Julien, H. Content analysis. In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods; Given, L.M., Ed.; SAGE Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2008; Volume 2, pp. 120–121. [Google Scholar]

- Porlán, R.; del Pozo, R.M.; Rivero, A.; Harres, J.; Azcárate, P.; Pizzato, M. El cambio del profesorado de ciencias: Marco teórico y formativo [Science teacher change: Theoretical and formative framework]. Enseñ. Cienc. 2010, 28, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinidad-Velasco, R.; Garriz, A. Revisión de las concepciones alternativas de los estudiantes de secundaria sobre la estructura de la materia [Review of high school students’ alternative conceptions of subject structure]. Educ. Quím. 2003, 14, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin, K.; Fraser, B.J. What does it mean to be an exemplary science teacher? J. Res. Sci. Teach. 1990, 27, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garriz, A.; Nieto, E.; Padilla, K.; Reyes-Cárdenas, F.M.; Trinidad, R. Conocimiento didáctico del contenido en química. Lo que todo profesor debería poseer [Didactic content knowledge in chemistry. What every teacher should possess]. Campo Abierto 2008, 27, 153–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furtak, E.M. Linking a learning progression for natural selection to teachers’ enactment of formative assessment. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2012, 49, 1181–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porlán, R.; del Pozo, R.M.; Rivero, A.; Harres, J.; Azcárate, P.; Pizzato, M. El cambio del profesorado de ciencias II: Itinerarios de progresión y obstáculos en estudiantes de Magisterio [Science teacher change II: Itineraries of progression and obstacles in prospective teachers]. Enseñ. Cienc. 2011, 29, 413–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennion, A.; Davis, E.A.; Palincsar, A.S. Novice elementary teachers’ knowledge of, beliefs about, and planning for the science practices: A longitudinal study. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2022, 44, 136–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, N. Consistencies and Inconsistencies Between Science Teachers’ Beliefs and Practices. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2013, 35, 1230–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driver, R. Un enfoque constructivista para el desarrollo del currículo en ciencias [A constructivist approach to science curriculum development]. Enseñ. Cienc. 1988, 6, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo, J.I. ¿Por qué los alumnos no aprenden la ciencia que les enseñamos? El caso de las Ciencias de la Tierra [Why don’t students learn the science we teach them? The case of Earth Sciences]. Ens. Cienc. Tierra. 2000, 8, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valverde, M.; Sánchez, G. Futuros maestros: Qué piensan sobre su formación en ciencias y qué hacen en sus prácticas escolares [Prospective teachers: What do they think about their training in science and what do they do in their school practices.]. Investig. Esc. 2020, 102, 122–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| DIMENSIONS | DIDACTIC ORIENTATION | |

|---|---|---|

| Transmission of Ideas (T) Teacher-Based Orientation | Construction of Ideas (C) Pupils-Based Orientation | |

| Nature of Ideas (N) | NT1—Pupils, by themselves, do not have the capacity to spontaneously elaborate ideas about the natural and social world around them. | NC1—Pupils personally interpret the information they perceive from reality. |

| NT2—Pupils’ ideas about scientific concepts are often erroneous and, therefore, not useful for learning such concepts. | NC2—The ideas which pupils often utilise in their daily lives constitute an alternative to scientific knowledge. | |

| Utilisation of Ideas (U) | UT1—Exploration of pupils’ ideas should be done at the beginning of a topic to determine the starting level. | UC1—Discussion of pupils’ ideas and interests throughout the teaching process is essential for learning science. |

| UT2—The results of the initial exploration of pupils’ ideas about a particular topic are of interest only to the teacher. | UC2—The manifestation of students’ ideas and interests throughout the teaching of a topic can lead to changes in the teaching planning. | |

| Change of Ideas (C) | CT1—Pupils learn when they mentally incorporate the scientific content taught; that is, when they are able to remember it. | CC1—Learning involves progressively reworking one’s own ideas through interaction with different sources of information. |

| CT2—Learning occurs when pupils’ conceptual errors are replaced by correct scientific ideas. | CC2—Pupils’ learning may be different from that intended by the teacher, even if the teaching is very well grounded. | |

| Orientation | Item | Mean (SD) | Mean of the Orientation (SD) | Z (T-C) | p (T-C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transmission of Ideas (T) | NT1: No spontaneous ideas | 2.15 (1.18) | 2.32 (1.14) | −6.012 | p < 0.001 |

| NT2: Wrong and unhelpful ideas | 2.50 (1.40) | ||||

| Construction of Ideas (C) | NC1: Ideas as personal interpretations | 5.30 (0.865) | 4.57 (0.69) | ||

| NC2: Ideas as alternative knowledge | 3.85 (0.99) |

| Orientation | Item | Mean (SD) | Mean of the Orientation (SD) | Z (T-C) | p (T-C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transmission of Ideas (T) | UT1: To determine the starting level | 5.15 (0.933) | 3.80 (0.785) | −3.857 | p < 0.001 |

| UT2: Only the teacher’s interest is useful | 2.45 (1.468) | ||||

| Construction of Ideas (C) | UC1: To discuss them throughout the process | 5.40 (0.995) | 5.30 (0.657) | ||

| UC2: To identify changes in planning throughout the process | 5.20 (0.768) |

| Orientation | Item | Mean (SD) | Mean of the Orientation (SD) | Z (T-C) | p (T-C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transmission of Ideas (T) | CT1: Mental incorporation | 3.90 (1.252) | 4.3 (0.923) | −3.997 | p < 0.001 |

| CT2: Substitution | 4.70 (1.174) | ||||

| Construction of Ideas (C) | CC1: Reworking | 5.25 (0.639) | 5.35 (0.360) | ||

| CC2: Learning other than intended | 5.45 (0.826) |

| DIMENSION | TOTAL | Transmission of Ideas | Construction of Ideas |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nature of Ideas | rs = 0.105; p = 0.354 | rs = 0.245; p = 0.127 | rs = 0.094; p = 0.565 |

| Utilisation of Ideas | rs = −0.064; p = 0.572 | rs = −0.168; p = 0.299 | rs = 0.032; p = 0.846 |

| Change of Ideas | rs = −0.070; p = 0.537 | rs = −0.156; p = 0.338 | rs = −0.017; p = 0.915 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Valverde Pérez, M.; Esteve-Guirao, P.; Banos-González, I. How Do Prospective Teachers Address Pupils’ Ideas during School Practices? Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 783. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12110783

Valverde Pérez M, Esteve-Guirao P, Banos-González I. How Do Prospective Teachers Address Pupils’ Ideas during School Practices? Education Sciences. 2022; 12(11):783. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12110783

Chicago/Turabian StyleValverde Pérez, Magdalena, Patricia Esteve-Guirao, and Isabel Banos-González. 2022. "How Do Prospective Teachers Address Pupils’ Ideas during School Practices?" Education Sciences 12, no. 11: 783. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12110783

APA StyleValverde Pérez, M., Esteve-Guirao, P., & Banos-González, I. (2022). How Do Prospective Teachers Address Pupils’ Ideas during School Practices? Education Sciences, 12(11), 783. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12110783