1. Introduction

The OECD PISA (Program for International Student Assessment for the 2018 report (see [

1]) studies in recent years have revealed widespread difficulty for Italian pupils in science and mathematics. These difficulties have serious consequences on the scientific education of students, who will be increasingly required to participate in the public debate on issues involving scientific topics as informed citizens [

2]. Although several measures have been implemented locally over the past years to improve this situation, a coherent framework does not yet seem to emerge that can help in describing, interpreting, and overcoming students’ difficulties on basic topics in mathematics and science, and in physics in particular. In this article, we will focus on how high school students (10th grade) interpret linear functions in the context of linear functions and in one-dimensional (1-d) kinematics (uniform rectilinear motions). In particular, we will analyze the students’ ability to represent a linear function or a motion using different forms of representation: the objects of our research will be graphs, tables, and algebraic formulas.

The choice of kinematics as the area of our study is justified by the massive use in this field of different types of representations (graphs, equations, tables) and by the presence of known misconceptions that influence the understanding of the representations of motions. The choice of linear functions is due to the fact that, although this topic is targeted both in the middle and high school math syllabi, the PISA tests’ data show persistent difficulties of students in obtaining information from written texts and diagrams. Considering the definition of mathematics literacy given by PISA in [

1], namely the “students’ capacity to formulate, employ and interpret mathematics in a variety of contexts, including reasoning mathematically and using mathematical concepts, procedures, facts and tools to describe, explain and predict phenomena”, we chose to focus this research on the ability to obtain information from a specific representation, consequently identifying the same information in a different type of representation.

The didactic context chosen for this research consists entirely of a large audience of students from technical and professional institutes in a large city in the South of Italy. This choice responds to the need to investigate the difficulties encountered in the physical and mathematical field of a sample that national and international surveys indicate to be consistently below the average performance in the age group of 14–15 years. To understand possible reasons for these difficulties, in addition to the ability to solve the proposed exercises on linear functions and 1-d kinematics, we investigated the students’ ability in spatial reasoning, confidence in the answers given, and perceived orientation toward physics in math and physics, to show if and how cognitive and metacognitive variables affect the students’ performance.

In the next section, we will briefly review the results obtained so far in the research in physics education regarding the students’ difficulties in kinematics concepts (e.g., velocity), the related mathematical concepts (e.g., slope), and the typical representations (e.g., graphs). In the second, third, and fourth sections, we present the methods of analysis, the measuring instruments, and the results, respectively. In the concluding section, we will discuss the possible didactic implications of this study.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Instruments

In this study, we used several instruments. They are reported in

Appendix A (in English language, but they were submitted in Italian language), following this subdivision:

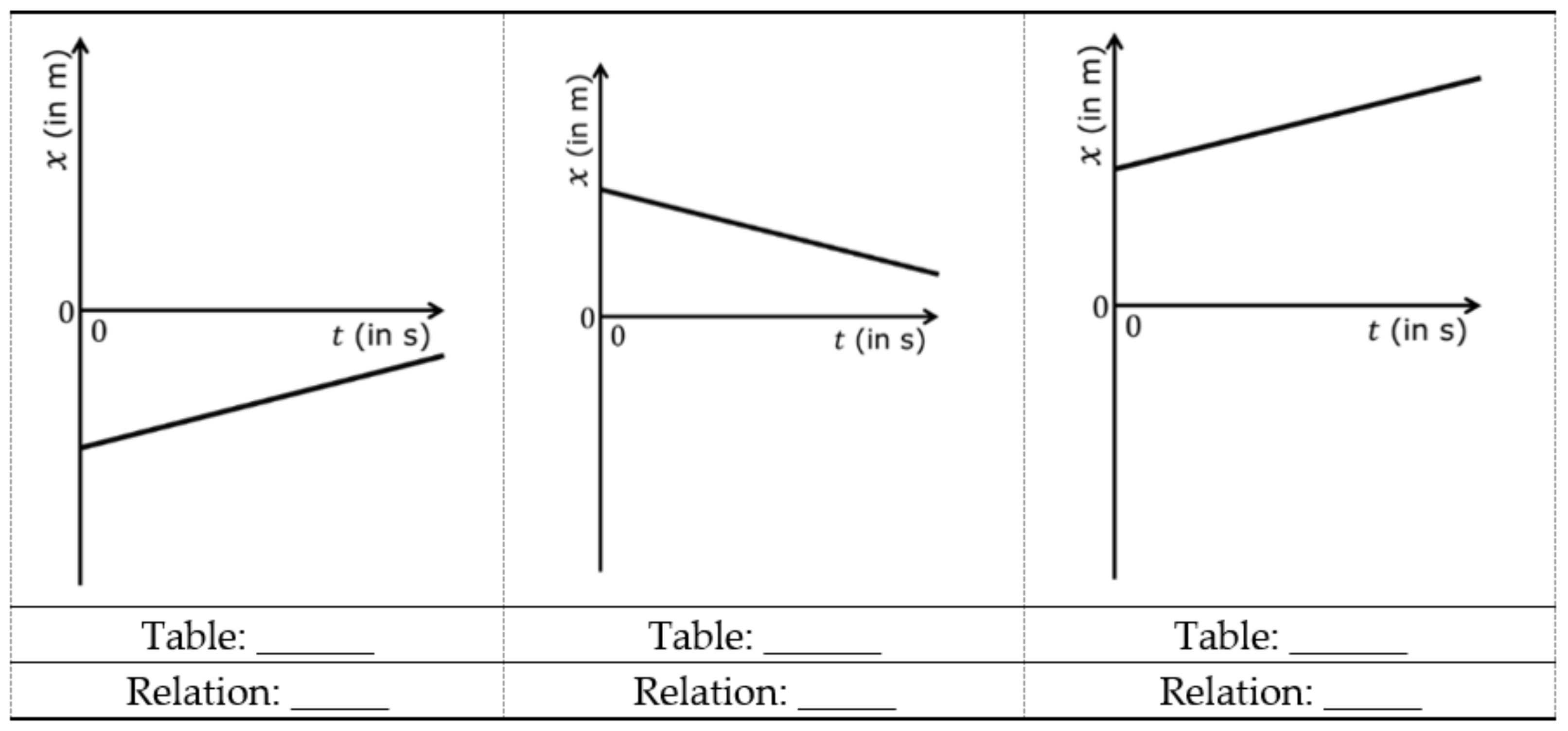

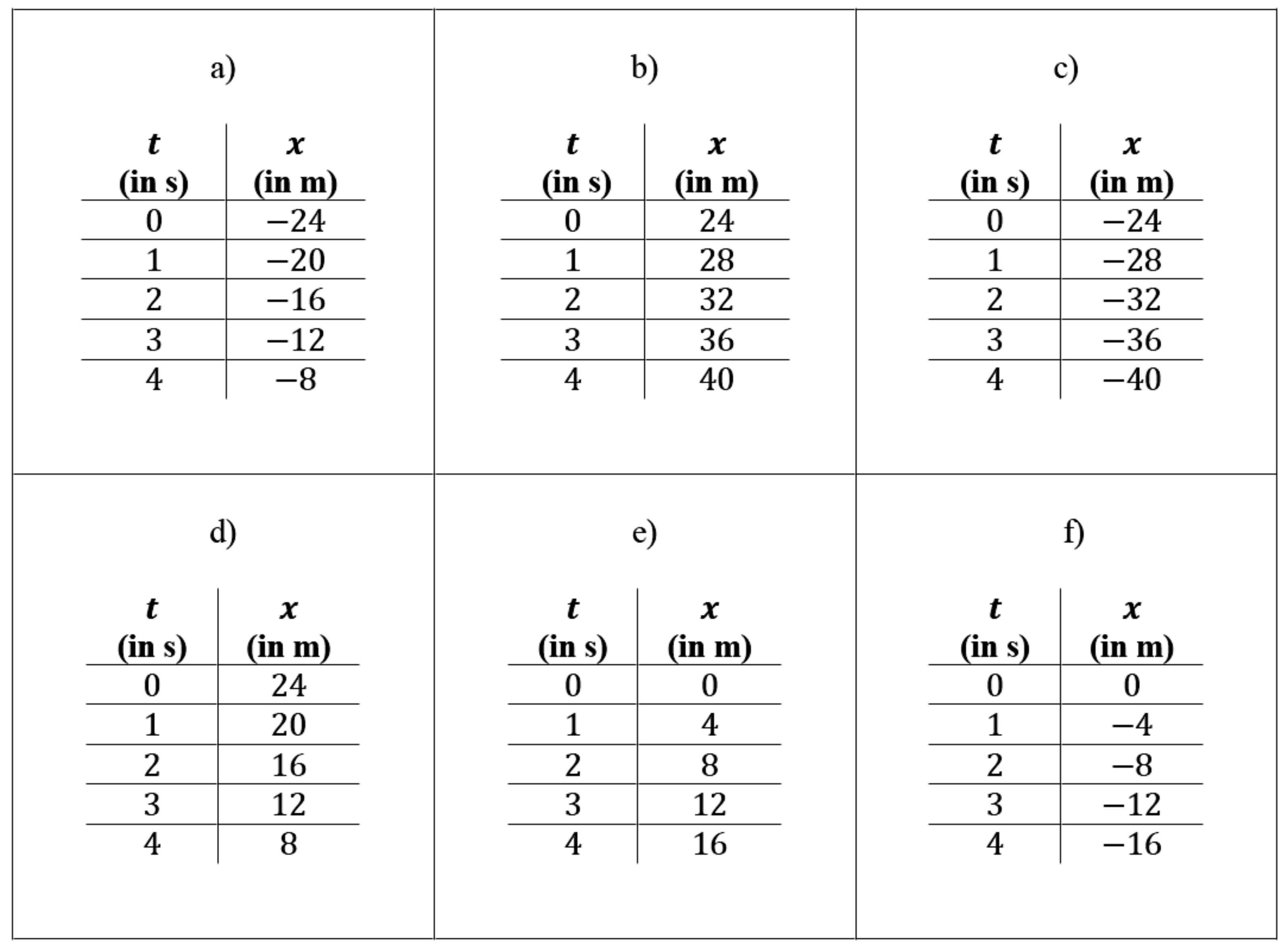

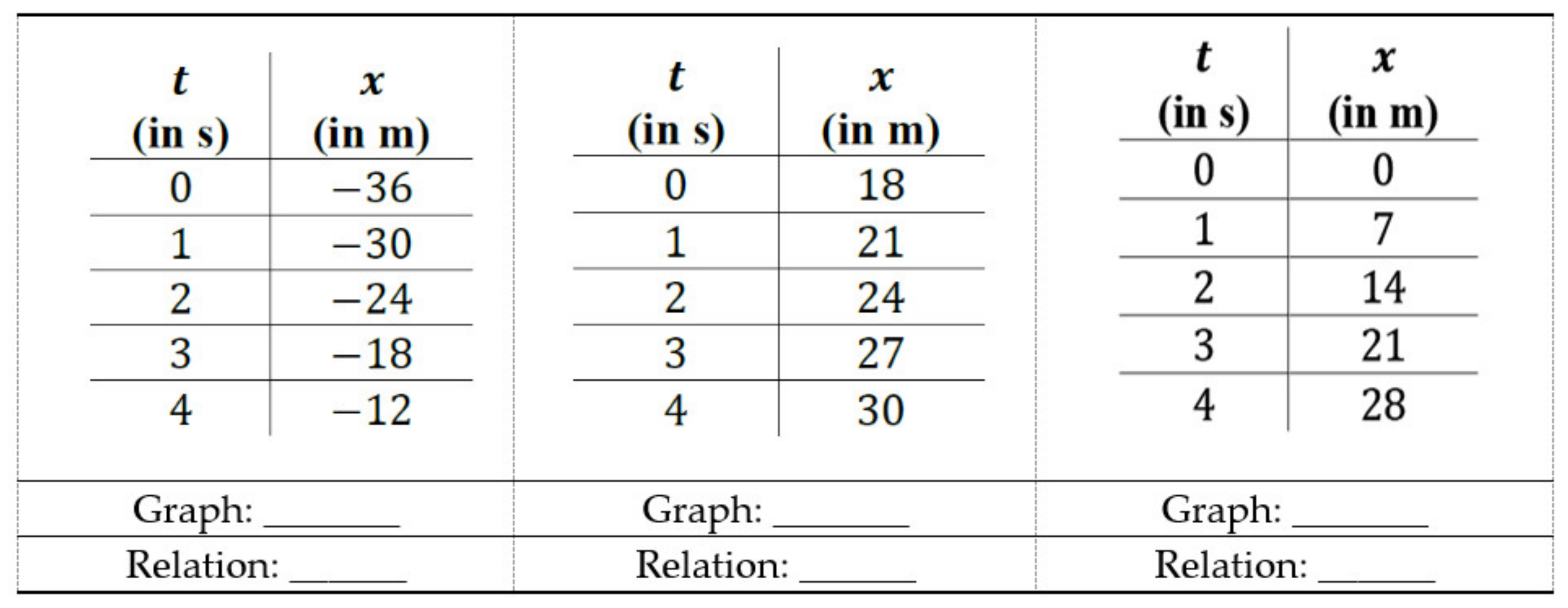

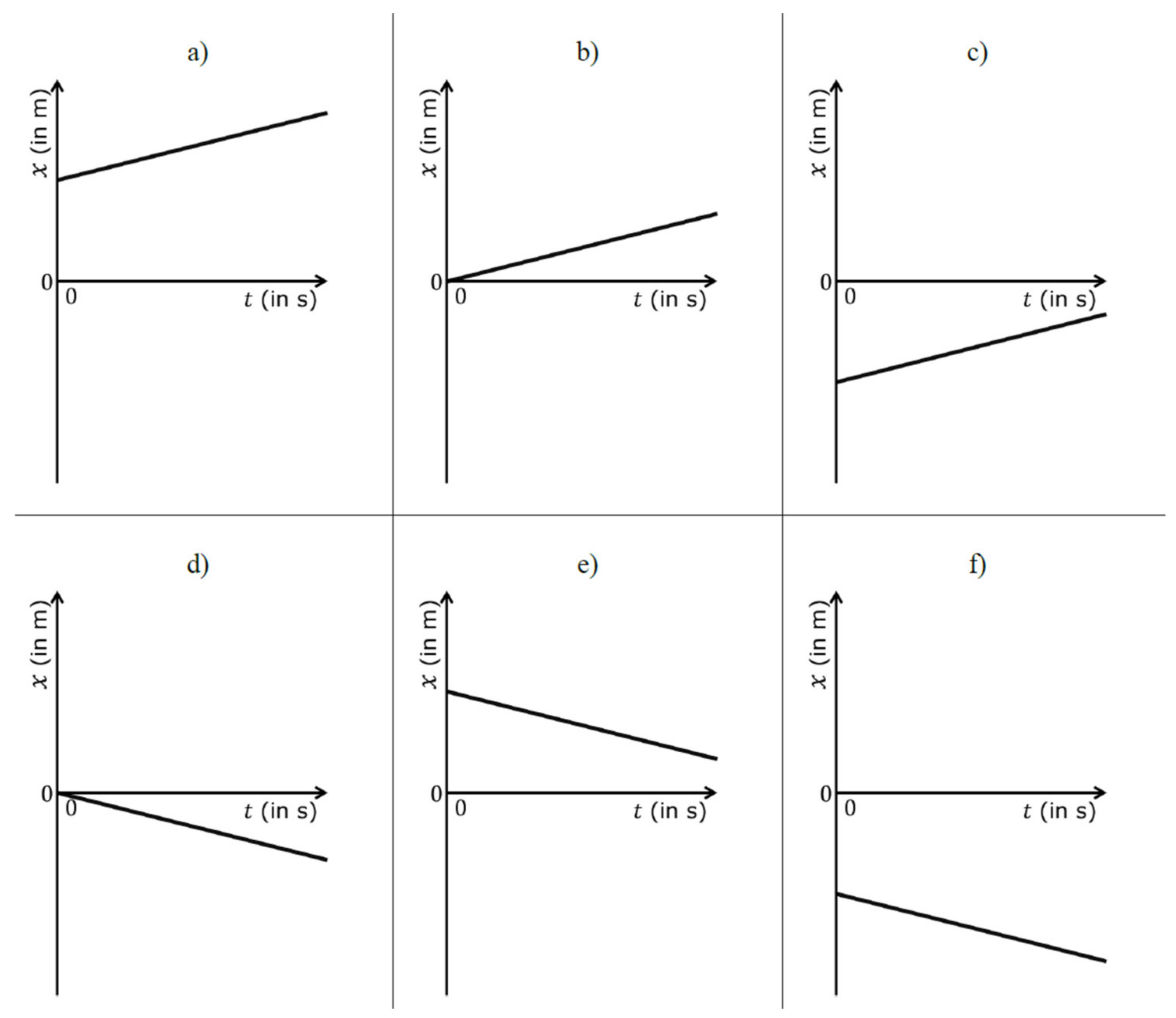

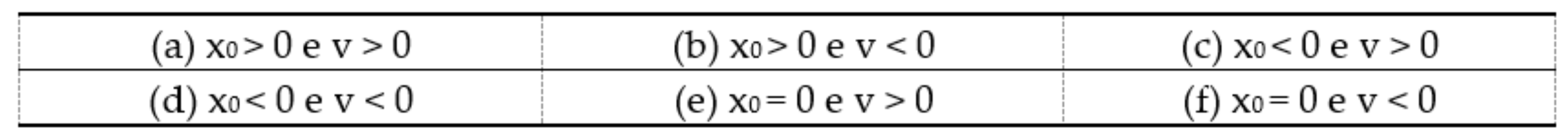

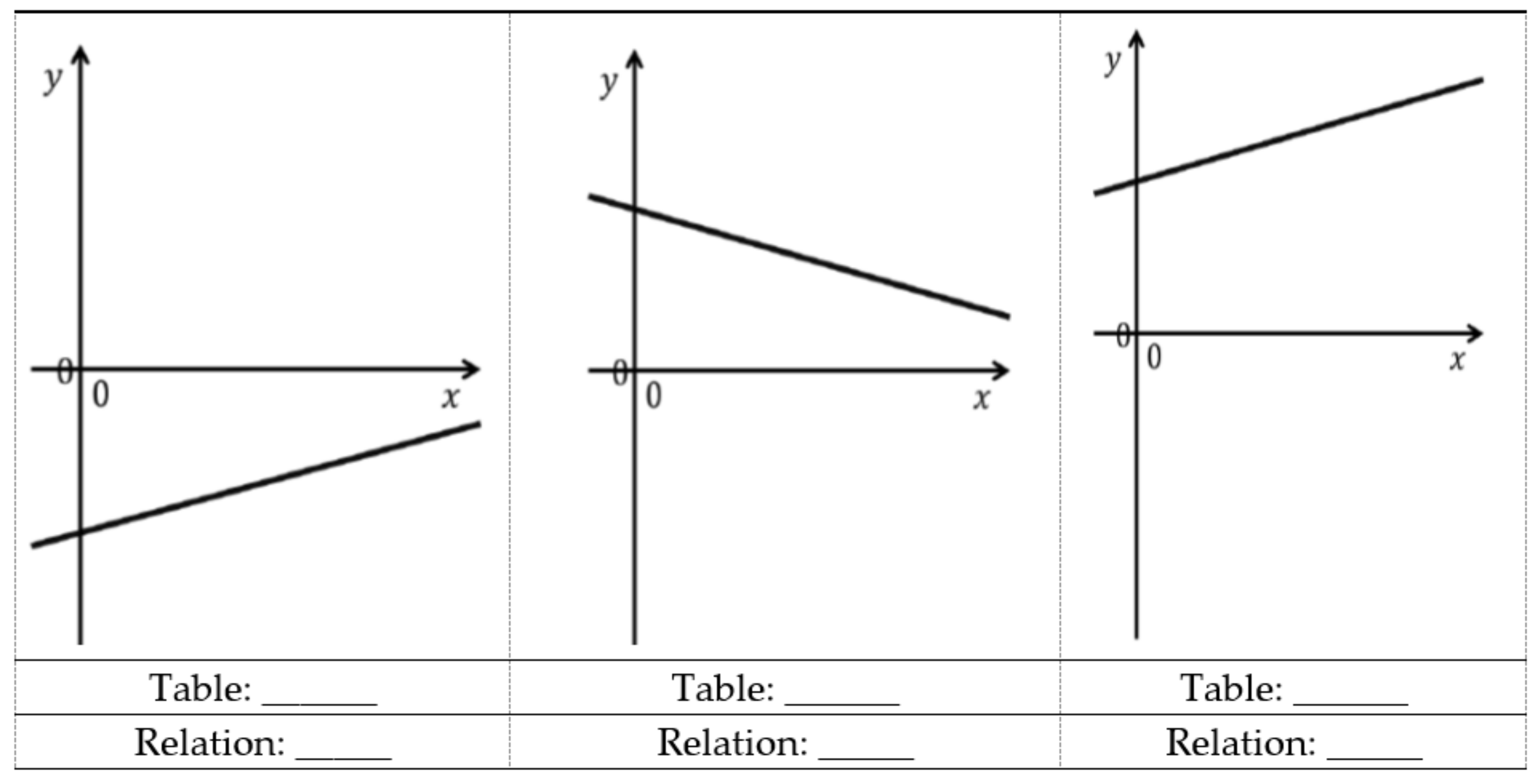

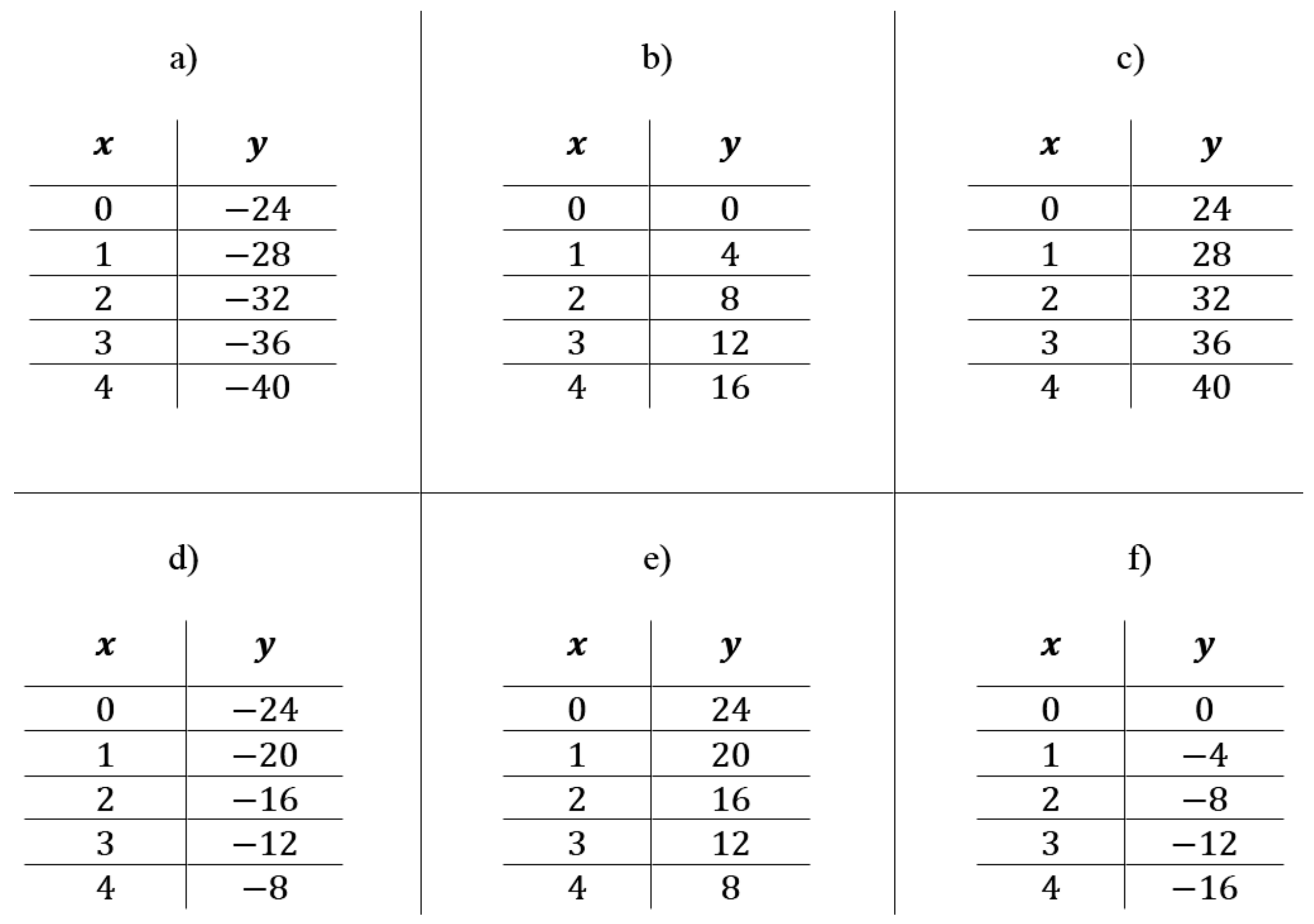

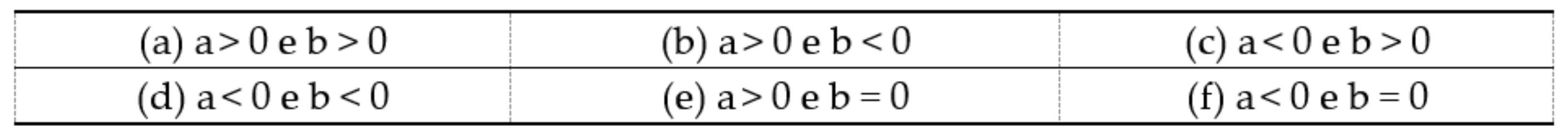

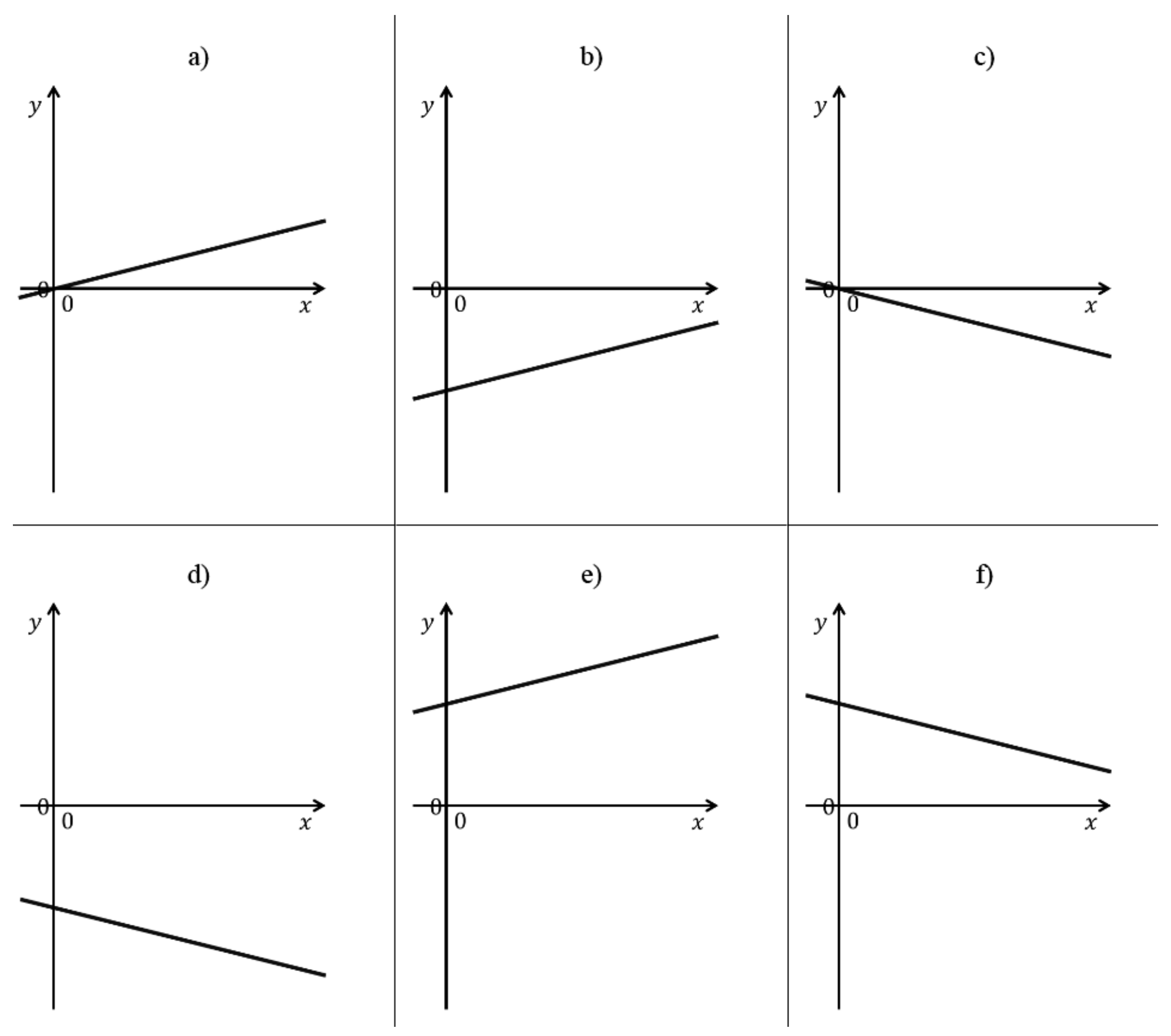

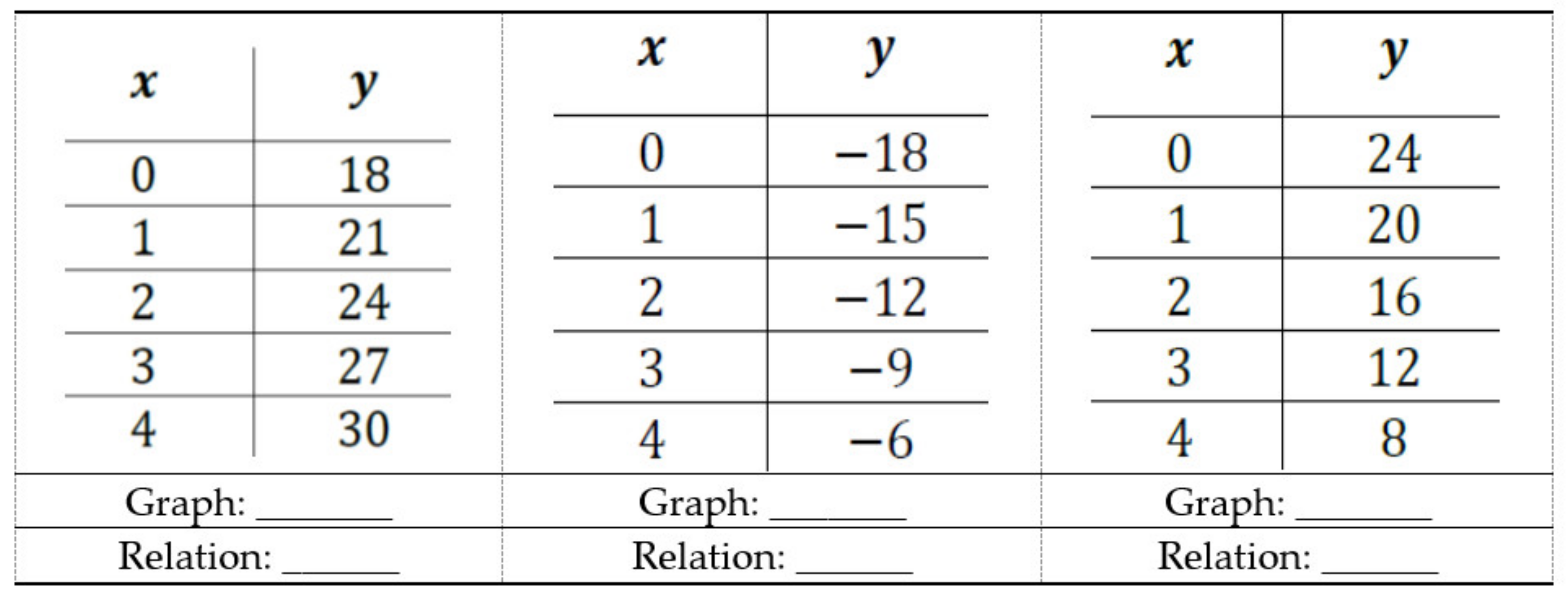

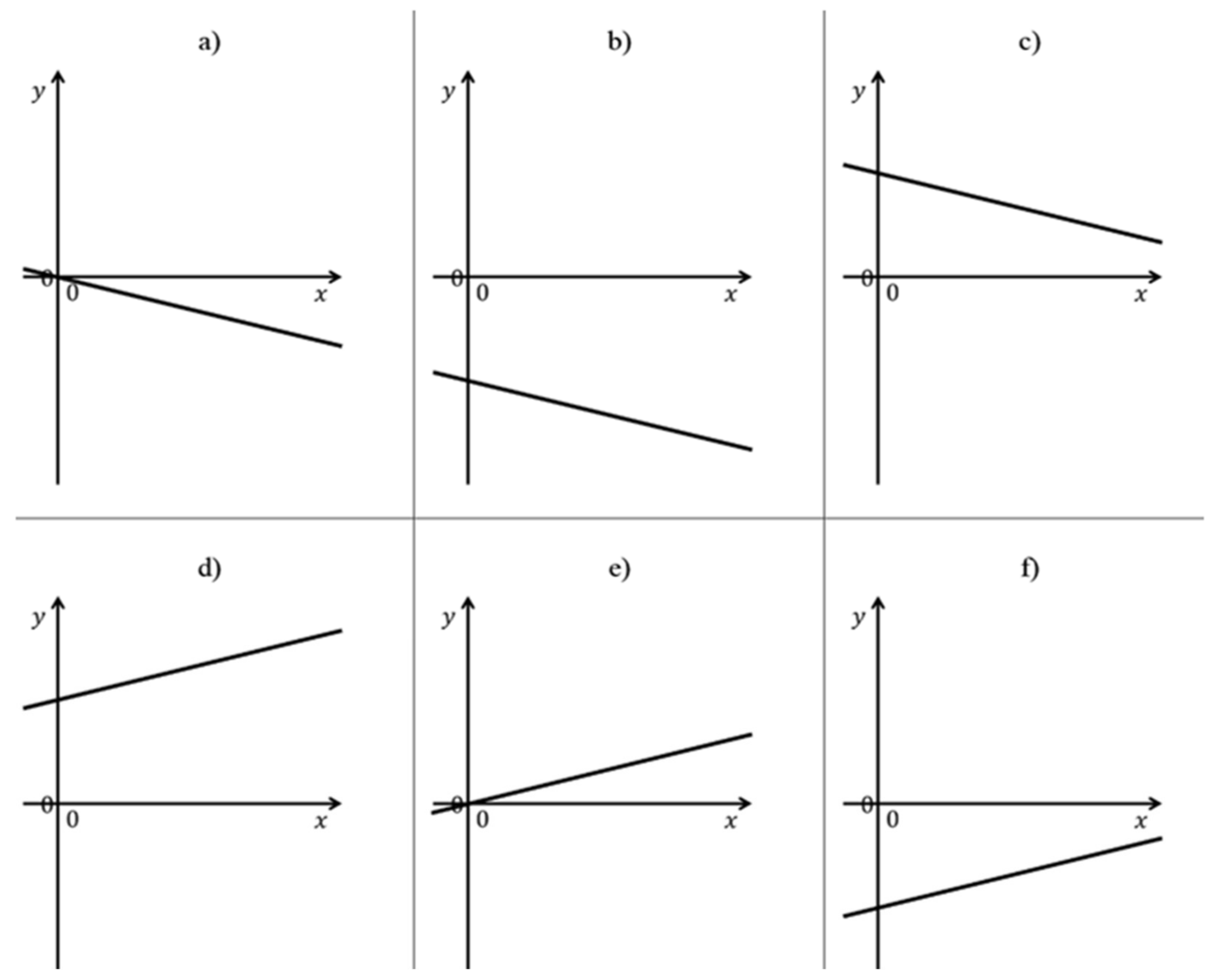

A kinematics test, concerning the laws of uniform rectilinear motions, composed of twenty multiple choice questions divided into three groups (respectively of six, eight, and six questions). The groups are characterized by a specific representation of the law of motion (table, graph, or algebraic relation). It is required to identify the other two corresponding representations, among six possibilities: these correspond to six types of linear functions, which are obtained by combinations of the sign of the angular coefficient and the intercept value at the origin, as described below.

A mathematics test, concerning linear functions, with the same structure as the physics test.

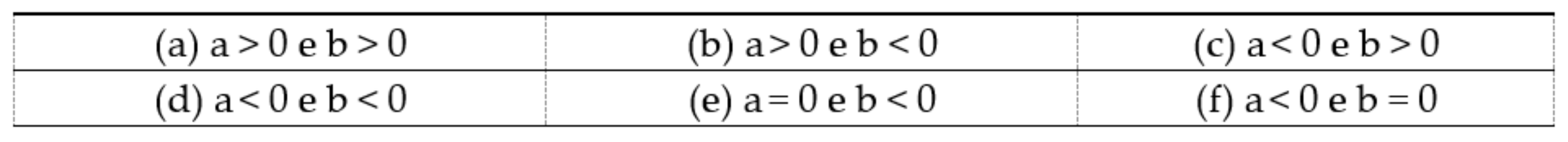

In these two tests, we used three types of representations: R = algebraic relation, G = graph, T = table. Consequently, we have six possible transitions, and they will be indicated in the following ways: GT, GR, RG, RT, TG, TR, where the first letter indicates the initial representation and the second the corresponding one that students are asked to identify. Regarding the classification of linear functions, we will characterize the questions according to the following notation: PP, PZ, PN, NP, NZ, NN, where the first letter indicates the sign of the angular coefficient and the second that of the intercept value at the origin (the letters P, Z, and N represent respectively positive, null, and negative values). The two contexts, mathematics and physics, differ slightly in the number of questions per type of function.

In drafting the two tests, attention was paid to some details in order to facilitate the exercises’ solution. For instance, in the graphs of the laws of motion, only the first and fourth quadrants are shown to make evident the start of motion in the origin of the time axis, while in the mathematics section a small section of the second and third quadrants is reported to show that the domain of the function is given by the whole real axis. In addition, no numerical values other than the origin are shown on the axes, to avoid the use of numbers when not necessary, with any calculation errors. Furthermore, all tables show the same values of the independent variable: 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4. In fact, the use of integer and equidistant numbers facilitates the deduction of the slope, if the student is mnemonically induced to apply the analytical formula for its calculation. In particular, for functions with negative origin intercept, the tables show only negative values of the dependent variable.

The possibility to directly compare the results obtained by students in responding to the kinematics and mathematics items is guaranteed by the fact that both require the same procedures for the resolution: the student should recognize the sign of the two parameters that characterize the line, finding the two corresponding representations consequently. Thus, it is not necessary to know any formula for the explicit calculation of the values of these quantities (which, however, could only be carried out starting from the tables’ values).

A questionnaire about self-confidence in which students are asked to express, for each group of physics and mathematics questions, the level of confidence in the answer given. This is done through a linear measurement scale (Likert scale) ranging from one (“not at all”) to five (“totally”).

A questionnaire about the orientation toward physics, specifically developed for this study on the basis of literature, consisting of 30 statements for which the student must indicate their level of agreement, on a scale from one (“not at all”) to five (“completely”). The questionnaire is reported in the appendix.

The Mental Rotation Test (MRT) (see [

18]). It consists of 20 multiple choice questions in which the respondent is asked to indicate out of four three-dimensional figures proposed, which correspond to a correct rotation of the figure present in the frame. Each question presents two correct and two wrong alternatives; the wrong ones correspond to a reflection of the figure itself and to a rotation of the figure present in another question. Usually, a restrictive evaluative criterion is used, considering only the answers with both correct alternatives as the correct ones.

Students had 45 min to complete the test, divided into three parts of 15 min each.

3.2. Sample

The sample of the research was made up of 643 high school students, whose age was between 14 and 15 years old. The percentage of girls in the sample was about 33% (N = 214). The participants were from seven different schools in a large city in the South of Italy, attending the second year of their high school course. All students attend the same type of study course, mainly focused on technical subjects and little on physics, thus constituting a homogeneous sample.

The classes, through their teachers, have been involved in the study voluntarily, having given their consent to take part in the research.

All the following steps of the data analysis were carried out by means of the SPSS statistics package.

3.3. Reliability

In

Table 1 the values of the McDonald’s Omega index for each of the instruments are reported. All reliability values are satisfactory (McDonald’s Omega > 0.8), so the following results can be considered representative of the population under investigation.

Data imputation techniques were implemented to replace blank answers, in the following way: for the instruments characterized by the dichotomy in correct/wrong answers (physics, mathematics, and MRT) all cases corresponding to no answer given were considered incorrect. For instruments characterized by responses on a Likert scale (self-confidence and orientation toward physics), we used the median value of the group of participants coming from the same school, for the corresponding item.

3.4. Scoring of Tests on Kinematics and Mathematics

The analysis of the tests was carried out by assigning 0 points to the wrong answers and 1 point to the correct ones. Initially, the overall performance of the two tests was assessed through the total score, obtained by adding those of the individual questions. Subsequently, average scores were calculated on the groups of questions sharing the same type of transition or function, separately for the two contexts, kinematics and mathematics. A paired-sample t-test was performed to observe the difference between the scores in physics and mathematics on these groups of questions. Then, exploratory factor analysis was carried out, taking into account both the kinematics and mathematics tests, in order to identify any common latent dimensions relating to the interpretation of representation modalities in mathematics and physics. The “parallel analysis” method was used to choose the number of optimal factors, namely comparing the results obtained with those generated by a random matrix. The McDonald’s Omega was then recalculated for each of the latent factors found, to assess their reliability.

3.5. Confidence Bias

Average confidence scores were first calculated separately for the two contexts for the groups of questions that share the same starting representation (e.g., a table, a graph, a formula). Then we normalized the obtained scores (values between +0.2 and +1) and subtracted the normalized average scores of the corresponding group of knowledge questions (values between 0 and +1), obtaining an estimate of the accuracy of self-evaluation. Note that, in this way, the range of possible values for the accuracy of self-evaluation varies between −0.8 to +1. Due to the normalization of the confidence scale, values of accuracy of self-evaluation between 0 and +0.2 indicate that the student is averagely calibrated. Values between +0.2 and +0.4 indicate moderate overconfidence bias, while values greater than +0.4 indicate significant overconfidence bias. Negative values indicate under-confidence bias. Then, the average accuracy of self-evaluation scores was calculated and a paired-sample t-test was performed to study the differences between the physical and mathematical contexts, as well as the gender differences.

3.6. Factor Analysis of the Orientation toward Physics Questionnaire

Since we used a newly developed instrument, exploratory factor analysis was carried out on the orientation toward physics items, using the criterion of the inflection point in the eigenvalue graph to choose the number of latent dimensions to be considered. Items with loadings lower than 0.4 were not included in the final solution. Then, McDonald’s Omega was recalculated for each factor. Subsequently, the average scores for the obtained factors were calculated, and a paired-sample t-test was performed to evaluate the significance of the difference between these dimensions for the two contexts (kinematics and mathematics). Finally, gender differences for each dimension were assessed.

3.7. Scoring of the Mental Rotation Test

We assigned a score of 0 to wrong answers and 1 to correct ones of the Mental Rotation Test (MRT). For each participant, an average score was calculated, and gender differences were evaluated.

3.8. Linear Regression

Multiple linear regression analysis was carried out to investigate the influence of confidence, orientation toward physics, spatial ability, and gender on the mean scores obtained on the average score in the kinematics and mathematics knowledge questions, respectively, and on each of the latent factors found through exploratory factor analysis. The generic equation of linear regression is:

where: Y

quest is the normalized average score obtained on the kinematics and mathematics tests, and on each of the latent factors; α is a coefficient that estimates the constant effects not due to the independent variables; X

SC is the average normalized self-confidence score in kinematics and mathematics; X

OTP is the average normalized score for each of the factors of the orientation toward physics scale; X

SP is the average normalized score for spatial ability; X

G is the gender variable (coded as 0 for males and 1 for females); ε is the estimate of the regression error; β

i are the estimates of the normalized regression coefficients. The regression was carried out by means of the SPSS statistics package, following the “backward” method.

4. Results

4.1. Tests on Kinematics and Mathematics

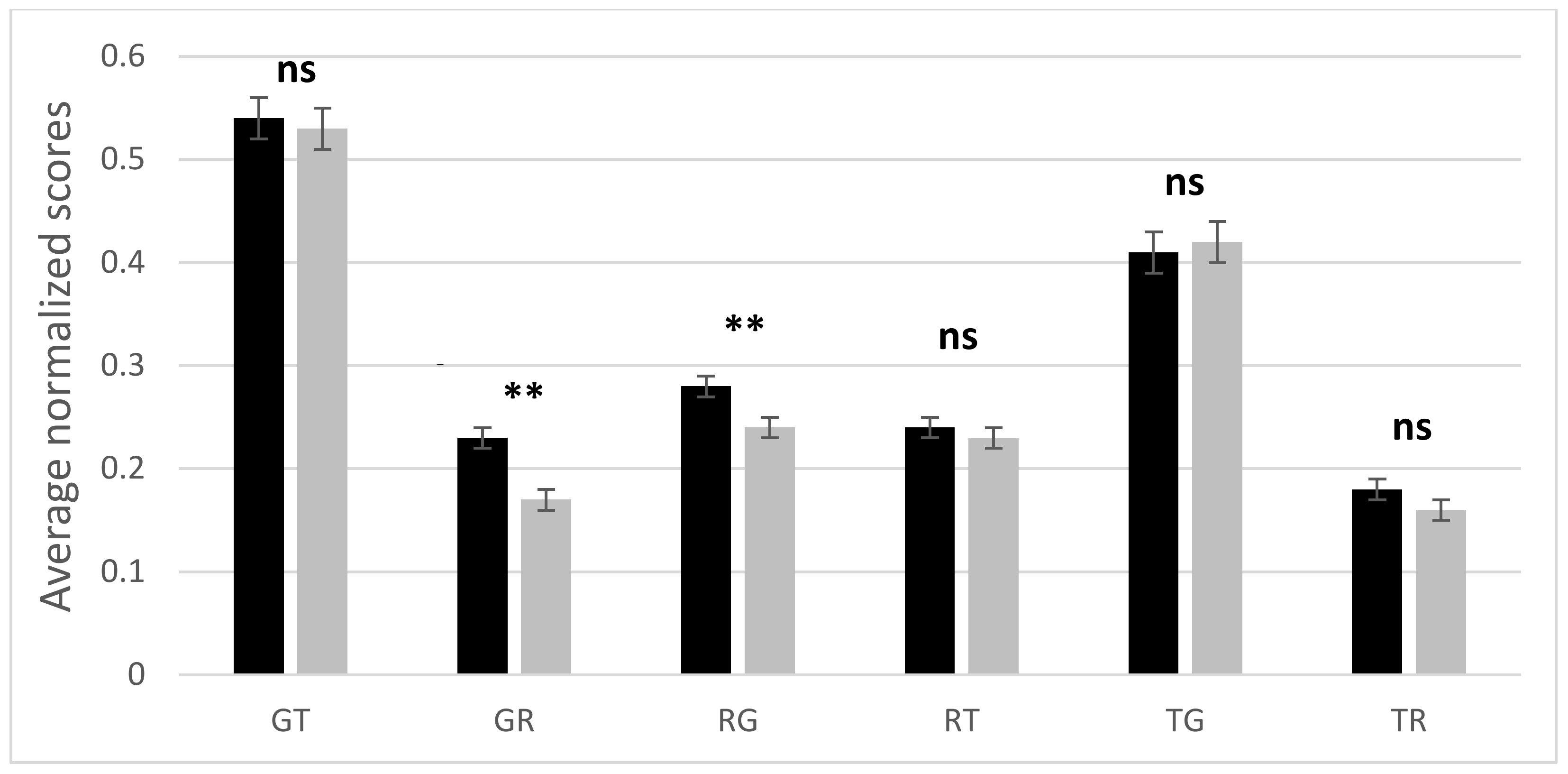

The average scores for the tests of kinematics and mathematics are (6.2 ± 0.2)/20 and (5.7 ± 0.2)/20, respectively. For most questions the frequency of correct answers is less than 50%, thus confirming that the sample involved in the study presents considerable difficulties in interpreting the graphical, tabular, and algebraic representations. In

Figure 1 the normalized average scores, for all groups of transitions in kinematics and mathematics, are reported.

A paired samples

t-test was carried out to compare the results for each transition in kinematics and mathematics. It is observed that the differences between the two contexts are significant only for transitions between graphs and formulas (in both verses). The participants reported better results with transitions that exclude formulas, while for the other transitions the average scores are higher when the formula is the starting representation. The analysis considering the types of function is shown in

Figure 2.

The differences between the scores in kinematics and in mathematics are significant, except for decreasing functions with negative values. In general, the functions of type PP (i.e., increasing with positive values) are the simplest to deal with. There is a highly significant difference in the understanding of transitions for increasing and decreasing functions, both in kinematics (average score for increasing function = 0.32 ± 0.01; average score for decreasing function = 0.29 ± 0.01; t (642) = 4.633, p < 10−3, d = 0.18) and in mathematics (average score for increasing function = 0.30 ± 0.01; average score for decreasing function = 0.27 ± 0.01; t (642) = 5767, p < 10−3, d = 0.14). The average score for the NN group of functions (i.e., decreasing with negative values) in mathematics is the only one higher than the corresponding one in physics, but the differences are not significant. This aspect shows that, in the mathematical context, the parameters of the linear functions are confused with each other more easily than in physics, especially in the case of PN and NP groups of functions. In fact, the question with the lowest percentage of correct answers (9.3%) occurs in mathematics with the TR transition for an increasing function with negative values.

These results suggest the existence of common latent factors in the interpretation of the transitions presented in the tests. Four factors were obtained from the exploratory factor analysis:

Factor 1 = Transitions between graphs and tables, which gathers 12 questions, six from kinematics and six from mathematics, that require a transition between a graph and a table, in both directions. The average score for these items is 0.48 ± 0.01, while the McDonald’s Omega of the scale is 0.92.

Factor 2 = Transitions with formulas in physics, which groups together 14 kinematics questions that present an algebraic relationship as a starting or final representation. The average score is 0.24 ± 0.01, while the McDonald’s omega of the scale is 0.91.

Factor 3 = Transitions from formulas in mathematics, which gathers eight mathematics questions that have an algebraic relationship as starting representation. The average score is 0.23 ± 0.01, while the McDonald’s omega of the scale is 0.87.

Factor 4 = Transitions toward formulas in mathematics, which gathers six mathematics questions that have an algebraic relationship as the final representation. The average score is 0.17 ± 0.01, while the McDonald’s Omega on the scale is 0.52. This value suggests that the last scale is not reliable.

Therefore, we proceeded to re-analyze the eigenvalues of the factor analysis, and we tried to choose only the first three factors, thus combining factor 3 and factor 4: the new factor gathers 14 items that share an algebraic relationship as starting or final representation. The average score is 0.20 ± 0.01, while the McDonald’s Omega is 0.86.

These latent dimensions suggest that solving problems with graphs and tables requires the same cognitive ability, regardless of the physical or mathematical context, while the presence of relationships brings out different reasoning as the context varies (mathematics or kinematics). Furthermore, the type of function does not influence the factorization, therefore the type of transition is the characterizing feature of each question. The average score on the first latent factor differs significantly from each of the other two factors (t (642) > 3.9, p < 10−3, d > 0.20).

4.2. Confidence Scale

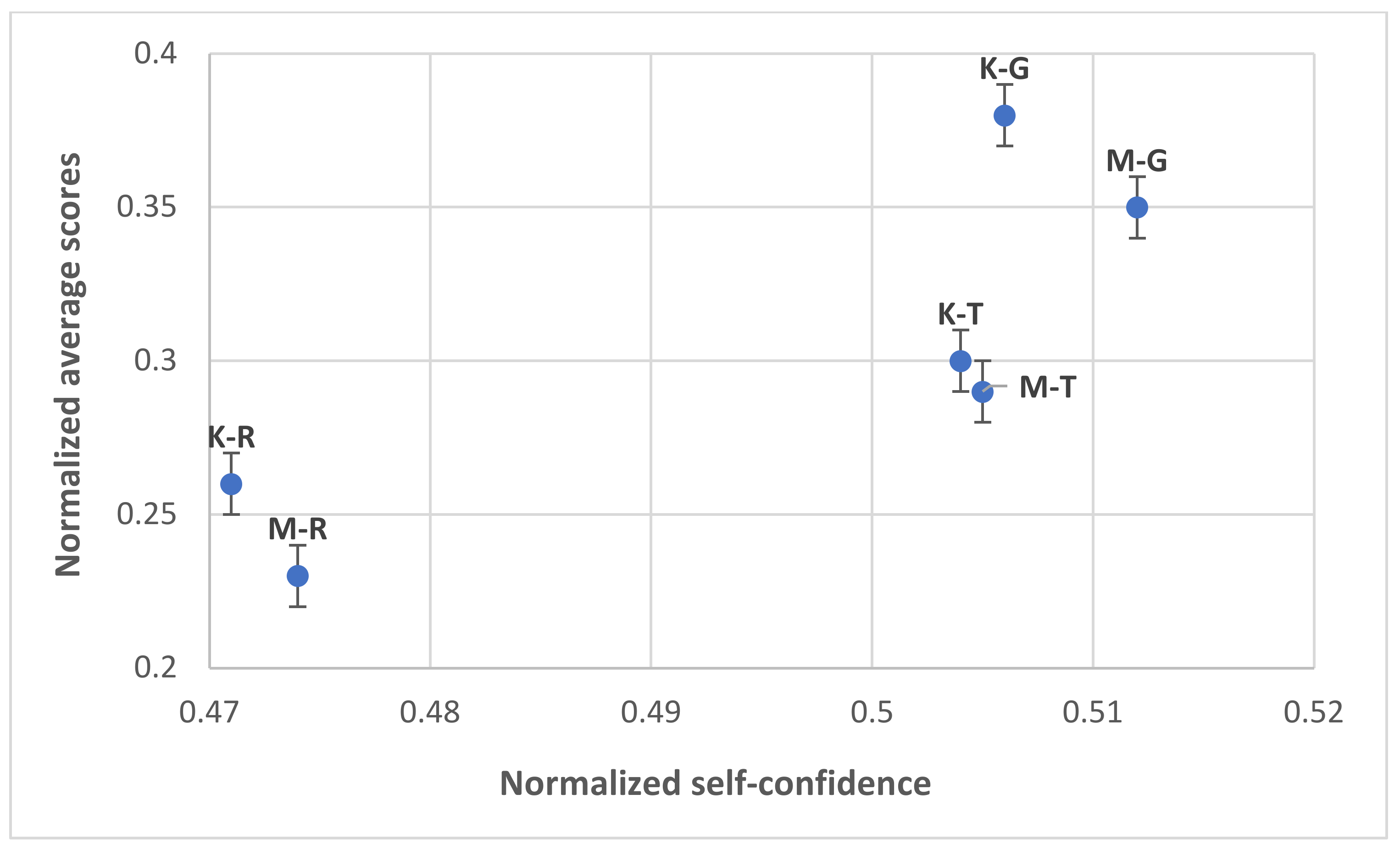

We report in

Figure 3 the normalized average scores for the groups of knowledge questions characterized by the same starting representation, both in kinematics and mathematics, as a function of the corresponding self-confidence (normalized) score. We note that students feel more confident when the starting representation is a graph and less confident when the starting representation is a relationship, especially in kinematics.

The participants are substantially calibrated both in kinematics (average overconfidence = 0.18 ± 0.01) and in mathematics (average overconfidence = 0.19 ± 0.01).

Figure 4 reports the normalized average scores for the accuracy of self-evaluation; paired samples

t-tests show that the differences between mathematics and kinematics are significant, except for the transitions with tables as starting representations. The accuracy of self-evaluation scores is higher in mathematics, probably because of the higher amount of study dedicated to it, compared to physics. Moderately over-confident students are on average (namely considering the average percentage for the six groups of transitions identified) about 30% of the total, while the percentage of significantly over-confident students is about 18%. There are no significant differences in the accuracy of self-evaluation due to gender.

4.3. Questionnaires about the Orientation toward Physics

From the exploratory factor analysis carried out on the orientation toward physics items, two latent factors emerged (see

Appendix B for the loading matrix), which we can interpret as follows:

The average scores for these two dimensions are shown in

Figure 5.

The other dimensions measured by the questionnaire, namely engagement and anxiety management, are excluded from the solution as the factor loadings of the corresponding items are lower than the established threshold.

We observe that the students show greater organization skills than problem-solving abilities: the differences between the two factors are statistically significant (t (642) = 8.213, p < 10−3, d = 0.60). The self-evaluation about problem-solving is significantly different between males and females (males’ average score = 3.09 ± 0.03; females’ average score = 2.89 ± 0.05; t (641) = 3.444; p < 10−3, d = 0.70), while for the first factor the differences are less significant (males’ average score = 3.17 ± 0.03; females’ average score = 3.30 ± 0.04; t (641) = −2.504; p = 0.13, d = 0.58).

4.4. Mental Rotation Test

The average score for the mental rotation test is very low (6.2 ± 0.2 out of 20). Gender differences in favor of the male gender are confirmed (males’ average score = 6.7 ± 0.2; females’ average score = 5.1 ± 0.3; t (641) = 4.371; p <10−3).

4.5. Linear Regression

We report in

Table 2 the standardized regression coefficients obtained from the linear regression analysis, together with the correlation coefficient and the variance explained. We chose gender, self-confidence (both in kinematics and mathematics), the two dimensions of the orientation toward physics, and spatial ability as independent variables (namely their average scores, as described above). The normalized average scores in kinematics and mathematics, as well as those related to the three factors extracted by these tests, were selected as dependent variables. Overall, we have five dependent variables, for which we carried out a different regression analysis. If an independent variable does not affect the dependent one, the regression coefficient is not significant (ns).

It is also observed that, as expected, the score in the Mental Rotation Test is strongly predictive for all the dependent variables considered. Similarly, perceived confidence in kinematics is predictive of the outcome in kinematics and in the transitions with formulas in physics. Conversely, perceived confidence in mathematics is predictive, especially for performance for mathematics items. Gender correlates negatively with performance in mathematics in a slightly significant way, but this does not happen in kinematics. On the other hand, the orientation toward physics has a different impact depending on its factors: the dimension linked to the organization skills and the elaboration of information does not influence the outcomes, while self-efficacy is a strong predictor, especially in mathematics and for transitions that do not include algebraic formulas.

5. Discussion

In this section, we discuss the results obtained, answer the research questions, and present some implications of the study.

5.1. How Does the Representational Fluency Differ between Mathematics and Physics?

From the analysis carried out on the kinematics and mathematics items, most of the difficulties emerge when dealing with representational fluency in mathematics. We observed that the differences between the two contexts (kinematics and mathematics) are significant especially when it is necessary to identify the correlation between graphs and formulas (in both directions). In particular, for graphs, the differences between mathematics and physics also emerge in the case of elementary functions, such as those increasing and with positive values. The literature has shown that it is often difficult to distinguish a graph of the law of motion from the corresponding trajectory, but we would expect that in the mathematical context, where the variables play a more abstract role, it will be easier to interpret a y(x) function on an x-y plane through a system of Cartesian axes. Despite this, our data do not support this hypothesis, confirming the idea that, for instance, a kinematic graph can help students to understand the information reported in a table. About algebraic relations, the existence of two different factors relating to transitions with formulas, one in physics and the other in mathematics, suggests that the reasoning schemes adopted by students are different in the two contexts when they have to solve problems with algebraic relations. Conversely, tables and graphs seem to play the same role in the process of extracting and comparing information.

This interpretation can indirectly justify why students show misconceptions in kinematics that are resistant to traditional teaching, which is mainly focused on a training approach characterized by numerical manipulation of the quantities. Our findings thus suggest that a conceptual understanding of the phenomenon under study is not necessarily associated with the mathematical understanding of related formulas. Our study also shows that transitions involving algebraic relationships in physics are easier to understand for students than the same type of transitions in mathematics, although students’ perception is the opposite: in particular, students feel more confident in transitions with formulas in mathematics, while they give less correct answers in this context. This also happens with graphs and tables. These results also show that a lack of calibration about self-confidence can lead to not using all the cognitive resources necessary to solve this kind of problems.

5.2. How Does the Representational Fluency Differ between the Different Types of Linear Functions?

From the analysis carried out, difficulties mostly concern the interpretation of negative increasing functions and positive decreasing functions. Such evidence suggests a difficulty in understanding the meaning of the slope sign. This evidence also confirms that in these cases students apply reasoning based on plane geometry to interpret trends over time: for example, in the case of an increasing function with negative values, the line can be interpreted as the path of a body that moves away from the origin, but which at the same time approaches the abscissa. Similarly, in the case of a decreasing function with positive values, the line can be interpreted as the path of a body that moves away from the origin, following the hypotenuse of a right-angled triangle formed by the axes and the line. In both cases, the confusion between the law of motion and the trajectory is confirmed.

5.3. What Is the Influence of Self-Confidence, Orientation toward Physics, Spatial Ability, and Gender on Representational Fluency in Mathematics and Physics?

Data analysis confirms the role of spatial ability in the correct interpretation of graphs in both kinematics and mathematics. This is coherent with the results obtained by the authors of [

12], who found correlations very similar to ours (between 0.28 and 0.32) between spatial ability and problem-solving skills which involve the interpretation of graphs, such as those of force and acceleration. As for the other independent variables measured in this study, the predominant role of confidence as a predictor of students’ performance is confirmed. In particular, the confidence in kinematics questions significantly influences not only the total score, but also the latent factor which represents the ability to interpret the transitions between graphs and tables, and the transitions with formulas in kinematics. Self-confidence in mathematics has a significant impact on the total score, while on the latent factors the effect is lower. Paradoxically, although slightly better results have been obtained in physics, the students show higher confidence in mathematics than in kinematics. This evidence confirms the results of international comparative studies (such as [

19]) for which the perception of confidence is an index of how well students evaluate their knowledge, helping them to plan their study and review it critically. In our case, the participants do not show a relevant overconfidence bias, that is, they do not significantly overestimate themselves. The substantial calibration is justified by the fact that students, both in kinematics and in mathematics, show that they generally feel less confident in their own answers—on a scale from 1 to 5, the average score is about 2.5—especially when the starting representation is a formula, despite being a type of representation widely used in school practice. This result confirms that these students need to improve not only the preparation but also their perception of this preparation, as the latter can negatively impact performance and motivation in answering standardized questions correctly.

In our model, gender does not influence students’ performances, as well as the self-regulation and metacognition dimension, while self-efficacy is confirmed as the strongest predictor among the other dimensions of the “orientation toward physics” construct, as was expected looking at the literature [

20].

The results of these linear regressions have to be interpreted within some limitations. First of all, the variance explained by the models is always lower than 30%, which is not a good percentage. Spatial ability was measured by a standardized instrument, as well as the performances in kinematics and mathematics, from which we were able to grasp the particular role played by the algebraic relationships in both contexts. Probably, the tool regarding the orientation toward physics should be improved in terms of several constructs, as the dimension representing engagement in the learning process could play an important role in predicting the students’ outcomes. We could not perceive it because of the distribution of the factor loadings, from which the distinction between the metacognitive activities regarding the information’s elaboration and the self-regulation of the study activities does not emerge, representing another result we did not expect. Furthermore, some of these dimensions could play a role as a mediator of the relationship, but in order to measure these effects we should be sure to deal with reliable variables. This is the way to improve the significance of the results presented, which can represent an exploratory base from which to start, also involving participants coming from different school courses and in an international context.

Finally, we can observe that the physics field in the “orientation toward physics” does not play a specific role, as it can be replaced with a more general study field, given the items’ formulation.

6. Conclusions

The aim of this research was to highlight how different representations of linear phenomena, such as uniform rectilinear motion, stimulate students’ different reasoning and resolution strategies. The results of this study can be exploited in didactic interventions for the first years of high schools, in which different aspects of a phenomenon are modeled using elementary representations such as graphs, tables, and algebraic relationships also for domains other than the ones analyzed here (e.g., economy). Furthermore, our results suggest that students’ difficulties in physics could be addressed through better use of tables and graphs, which present fewer conceptual obstacles than that involving algebraic relationships. Considering these results, it is desirable that more effective and targeted training will make teachers aware of the potential and limits of the different types of representation.