Development of a Framework to Assess Challenges to Virtual Education in an Emergency Remote Teaching Environment: A Developing Country Student Perspective—The Case of Peru

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Virtual Instruction

1.2. Emergency Remote Teaching during Covid-19

- RQ1: What are the most common challenges students face in virtual instruction within the context of a pandemic?

- RQ2: What is the importance of these virtual instruction challenges from the students’ perspective?

- RQ3: Is it possible to assess the extent of challenges faced by online students?

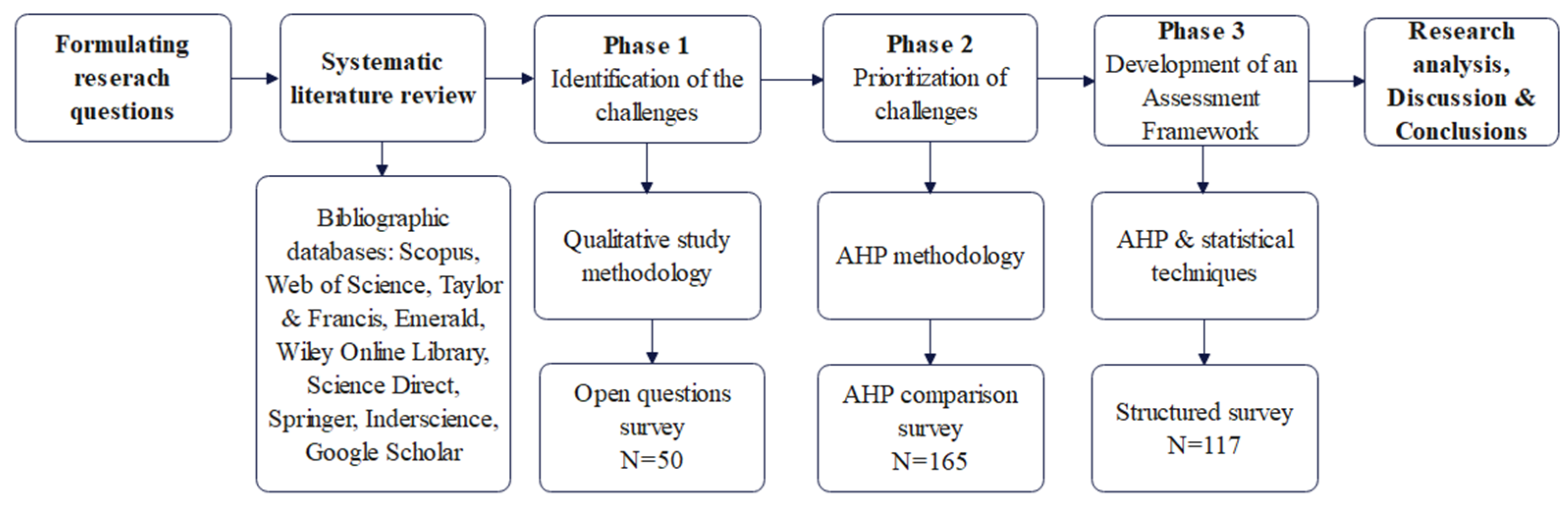

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodology for Phase I: Identification of the Challenges of Distance Learning

- RQ4. What problems do YOU face learning using virtual instruction?

- RQ5. What problems does YOUR INSTITUTION face using virtual instruction?

- RQ6. What problems does YOUR FAMILY face due to virtual instruction?

- RQ7. What INFRASTRUCTURE problems do you face at home using virtual instruction?

2.2. Methodology for Phase II: Prioritization of Challenges

2.3. Methodology for Phase III: Development of an Assessment Framework

3. Results

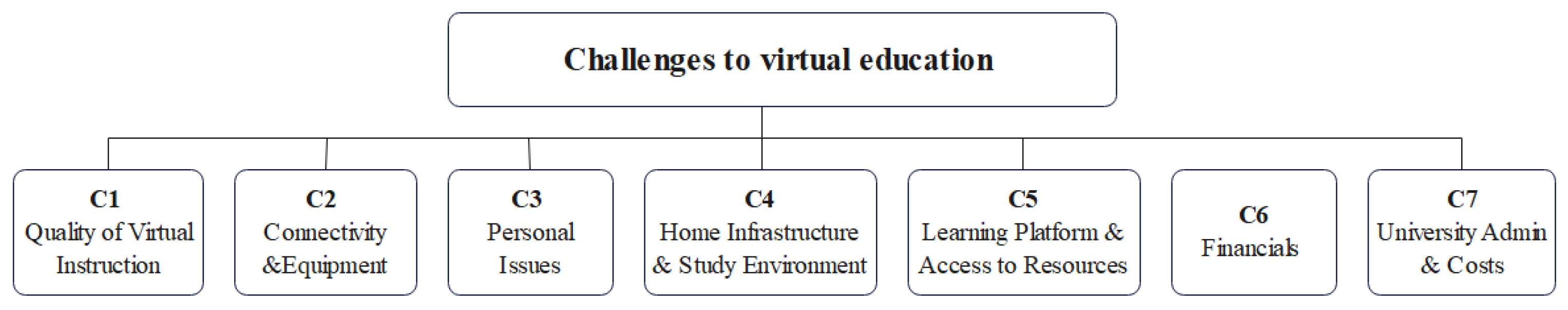

3.1. Phase I Results: Identification of the Challenges of Distance Learning

- C1—The perceived quality of virtual instruction

“Faculty are poorly trained to teach in a virtual environment”[C7P7_1]

“Instruction quality is lower”[C31P6_1]

“Class time is less than in physical sessions”[C13P6_3]

“The most important thing in my career is practice, which is difficult to do…”[C13P6_1] (an architecture student)

“Too many [exam] questions for such a short time”[C41P6_2]

“Class participation is not the same in a virtual environment”[C40P6_1]

- C2—Connectivity and proper equipment

“There are not enough computers [for everybody] at home”[C8P8_1]

“My brothers have to study online, and there are not enough computers for all of us”[C24P8_2]

“Connection problems in peak hours”[C48P6_3]

“Not all of us have the opportunity to have Internet access”[C6P7_1]

“More than 50% of students do not have Internet access”[C50P7_2]

“I think that internet access to both faculty and students is something…that could be improved”[C1P7_1]

“[University] servers cannot cope with the traffic”[C8P7_1]

- C3—Home infrastructure and study environment

“Too much noise and little space to study at home”[C36P8_2]

“I don’t have either a suitable chair or table, so I study in bed”[C26P9_1]

“I don’t have a suitable place to listen to my classes. I ask [my family] to be quiet”[C16P8_1]

“And there are three of us sitting at the same table”[C19P8_3]

- C4—Personal issues

“I do not have spaces for either recreation or sharing with peers”[C8P6_1]

“Get tired of spending so much time in front of a screen”[C39P6_1]

“I pay little attention to the class”[C26P8_2]

“I need to care for the little ones while my parents are at work”[C34P8_2]

“Lockdown gets young people depressed”[C11P6_5]

“[I have a] family, friends who are either sick or have died”[C18P6_1]

“They [university] don’t care about our mental health”[C20P7_4]

- C5—Distance learning resources

“Lack of expertise to use the platform by both teachers and students”[C50P6_6]

“I don’t have access to needed services (e.g., printer…)”[C30P6_7]

“Not having access to library books”[C18P6_1]

- C6—Finances

“I struggle to pay monthly university fees”[C31P6_2]

“[My family’s] economic problems [are] the main problem”[C50P8_1]

“Salary reduction for the only family provider”[C30P8_1]

- C7—University administration and costs

“University tuition has not decreased even though we are not using their facilities anymore”[C02P7_01, C41P7_01, C45P7_01]

“They [universities] have no concern for students economic situation. They ignore our requests to decrease tuition”[C21P7_02]

“University authorities and faculty lack leadership”[C51P7_01]

- Quality of instruction/learning;

- Poor Internet connectivity and lack of proper equipment;

- Personal and psychological issues;

- Lack of appropriate home infrastructure.

- Learning platform and access to resources;

- Financial issues related to students and families;

- General concerns related to the university and others.

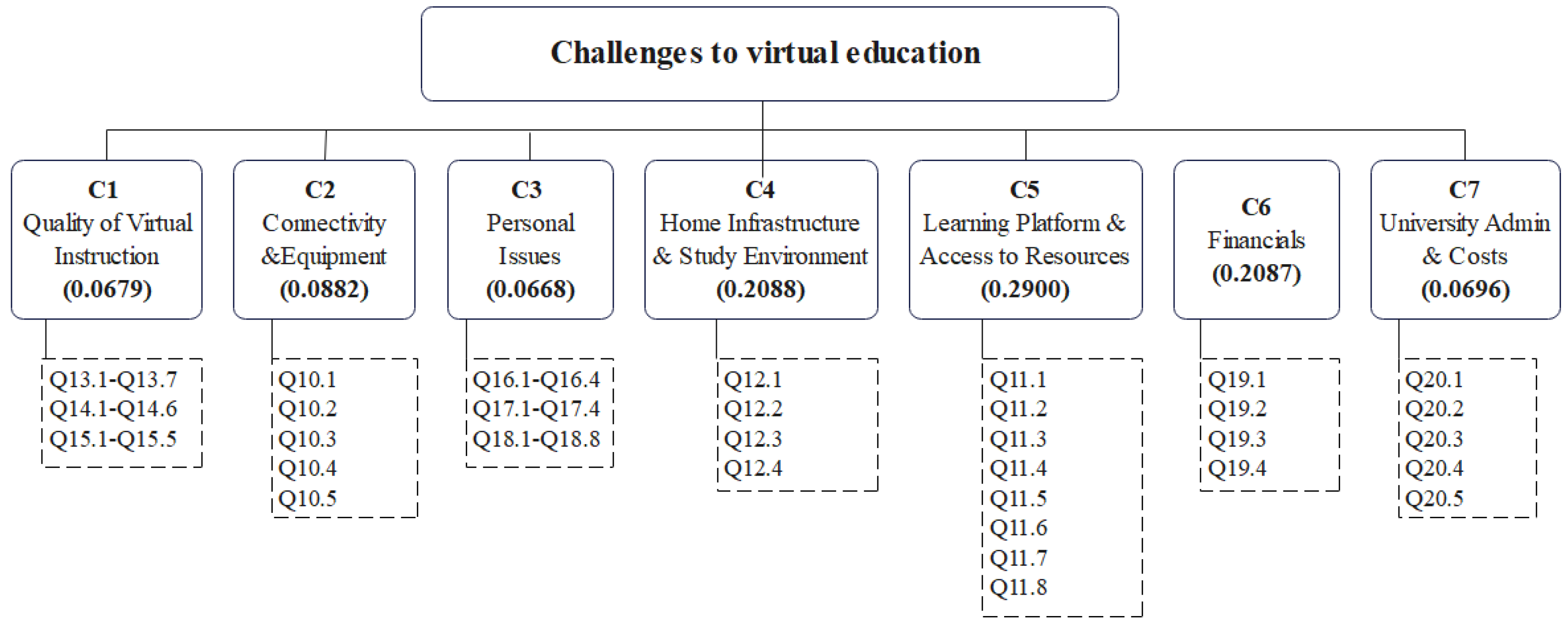

3.2. Phase II Results: Prioritization of Virtual Instruction Challenges

- C4—Lack of proper home infrastructure and study environment (W4 = 0.2088);

- C5—Learning platform and access to resources (W5 = 0.2900);

- C6—Financial issues related to students and families (W6 = 0.2087).

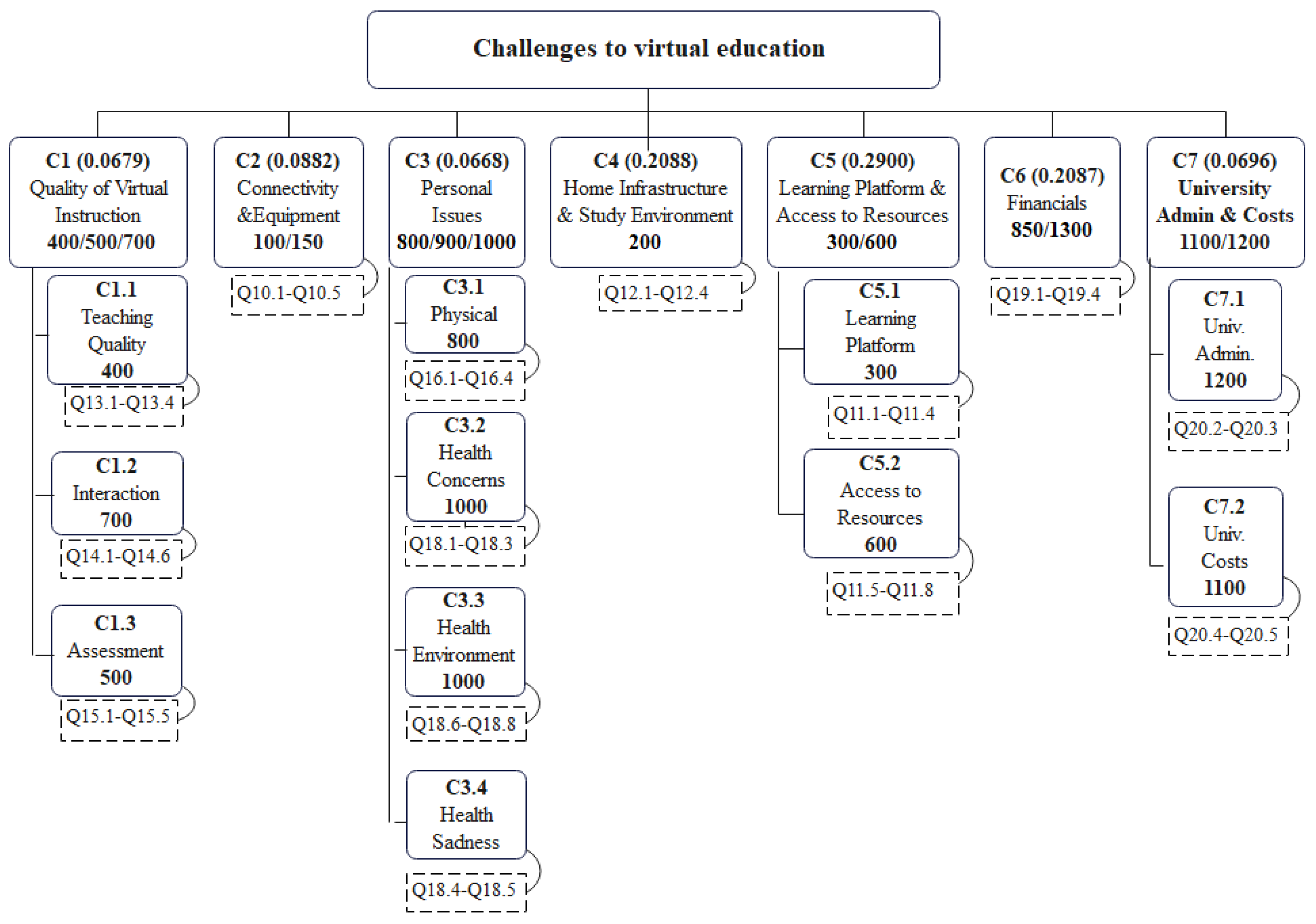

3.3. Phase III Results: Development of a Virtual Instruction Challenge Assessment Framework

3.3.1. Identification and Development of Relevant Indicators/Variables

3.3.2. Standardization of Variables to Allow Comparisons

3.3.3. The Weighting of Assessment Variables

3.3.4. Sensitivity Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- The qualitative research performed using the survey method allowed for the identification of the most frequently reported challenges and difficulties faced by students studying online in ERT environments:

- Perceived quality of virtual instruction (25%);

- Poor Internet connectivity and lack of proper equipment (22%);

- Lack of appropriate home infrastructure to study (17%);

- Personal and psychological issues (9%).

- The application of the Analytic Hierarchy Process helped prioritize the perceived importance of the most critical student challenges related to virtual education from the students’ perspective (three challenges constitute 70.8% of the overall significance):

- Distance Learning Resources: learning platform and access to resources (29%);

- Home Infrastructure: lack of proper home infrastructure (20.88%);

- Finances: financial issues related to students and families (20.87%).

- The use of the AHP and composite indictors have allowed for the development of an assessment framework to evaluate the nature and extent of the challenges faced by specific students or communities of students in ERT environments, making it possible to develop interventions to address those challenges.

- Provide careful instructional design and planning, using a systematic model for design and development [56].

- Consider online learning design options including the following nine dimensions: modality, pacing, student–instructor ratio, pedagogy, instructor role online, student role online, online communication synchrony, the role of online assessments, and source of feedback [51].

- Provide structured and planned educational material (content, methodologies, and shared goals) and more adequate e-learning platforms by using suitable interactive digital learning resources (video, animations, quizzes, and games) to maintain students’ attention [53].

- Survey students about their capacity to engage in remote learning, including areas such as equipment, family responsibilities, home environment, etc. This information is needed to understand how realistic it is for students to adapt to instructors’ plans for delivery and to work with instructors to adjust them according to student capacity to participate in distance learning [57,58].

- Ensure the reliability of the selected technological delivery systems, the provision of and access to learner support systems, support for faculty professional development for online teaching pedagogies and tools, policy and governance issues related to distance program development, and quality assurance [12].

- Implement a blended approach to reinforce a feeling of community belonging. Increasing interaction (student–content, student–student, and student–teacher) increases the learning outcomes when meaningfully integrated. According to experts, students need face-to-face interactions, so face-to-face lessons should complement online classes [53,59].

- Provide the opportunity for teachers to develop blended teaching competencies to prepare them to teach in different formats, settings, and situations and support their ongoing learning and growth related to teaching with technology [33].

- Develop more inclusive tools, platforms, and devices to make digital learning resources accessible to people with disabilities [53].

- Consider dedicated (financial, logistical, and pedagogical) support programs for at-risk students [58].

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. The Case of Peru

Appendix A.2. Digital Divide and Education in Peru

Appendix A.3. Virtual Education during the Pandemic in Peru

Appendix A.4. Virtual Education after the Pandemic in Peru

Appendix B

Appendix B.1. The Analytic Hierarchy Process in the Present Study

| Importance of Virtual Education Challenges |

|---|

| This survey intends to identify the importance of the challenges that college students face to succeed in their virtual learning in the context of the current pandemic. In this last section, we will ask you some questions regarding the relative importance of the above challenges. |

| 21. What is more important to you: “The availability of adequate Internet and computer connectivity” or “An adequate educational platform and access to resources (e.g., library)?” |

| 9. Regarding your answer to the previous question, how much more important is the chosen option? [Usethe intermediate values of the intensity scale if necessary] 1—Equally important 2 3—Moderately more important 4 5—Strongly more important 6 7—Very strongly more important 8 9—Extremely more important |

Appendix B.2. Number of Comparisons

Appendix B.3. Group Consistency

Appendix B.4. Deriving Priorities

Appendix C

Appendix D

Appendix D.1. Using the Challenge Assessment Framework

Appendix D.2. Original Scenario

Appendix D.3. Sensitivity Scenario I

Appendix D.4. Sensitivity Scenario II

| Line | Challenges | Global Weights | HIGHEST Challenged Case #18 Responses | AVERAGE Challenged Case Responses | LEAST Challenged Case #39 Responses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | C.1. Quality of Virtual Instruction | 0.0679 | |||

| 2 | C.1.1. Teaching | 0.0226 | 3.75 | 1.76 | 1.00 |

| 3 | C.1.2. Interaction | 0.0226 | 5.00 | 2.80 | 3.13 |

| 4 | C.1.3. Assessment | 0.0226 | 4.20 | 2.52 | 2.80 |

| 6 | C.2. Connectivity & Equipment | 0.0882 | 3.00 | 1.66 | 1.00 |

| 8 | C.3. Personal Issues | 0.0668 | |||

| 9 | C.3.1. Physical | 0.0167 | 5.00 | 3.13 | 3.50 |

| 10 | C.3.2. Health Concerns | 0.0167 | 4.33 | 3.06 | 3.33 |

| 11 | C.3.3. Health Environment | 0.0167 | 5.00 | 2.75 | 2.00 |

| 12 | C.3.4. Health Sadness | 0.0167 | 4.00 | 3.53 | 2.00 |

| 14 | C.4. Home Infrastructure & Study Environment | 0.2088 | 5.00 | 2.58 | 1.00 |

| 16 | C.5. Learning Platform & Access to Resources | 0.29 | |||

| 17 | C.5.1. Learning Platform | 0.1450 | 3.50 | 1.65 | 1.00 |

| 18 | C.5.2. Access to Resources | 0.1450 | 5.00 | 2.75 | 1.00 |

| 20 | C.6. Financial Problems | 0.2087 | 5.00 | 2.97 | 1.50 |

| 22 | C.7. University Admin. & Costs | 0.0696 | |||

| 23 | C.7.1. University Administration | 0.0348 | 3.50 | 2.40 | 2.50 |

| 24 | C.7.2. University Costs | 0.0348 | 4.00 | 4.06 | 3.50 |

| 26 | Original Scenario Total Scores (Weighted from survey responses) | 4.31 | 2.69 | 2.09 | |

| 27 | Sensitivity Scenario I (All criteria equally weighted) | 4.44 | 2.52 | 1.45 | |

| 28 | Sensitivity Scenario II (Only C4-C6 with equal weights) | 4.75 | 2.58 | 1.17 |

Appendix E

Appendix E.1. Challenges to Virtual Education Assessment10

- C1—Challenges to the Quality of Virtual Instruction

| C1.1. Teaching Quality. | |||

| Index | English Question | Survey | Spanish Question |

| C1.1.1 | Teachers are not trained to teach a virtual class in a didactic way | Q13.1 | Los profesores no están capacitados para dictar una clase virtual en forma didáctica. |

| C1.1.2 | Students do not have knowledge of how to study in a virtual class | Q13.2 | Los alumnos no tienen conocimiento de como estudiar en una clase virtual |

| C1.1.3 | Teachers teach fewer hours than they should | Q13.3 | Los profesores dictan menos horas de las que deberían |

| C1.1.4 | Teachers are not motivated to teach classes online | Q13.4 | Los profesores no están motivados a dictar clases en línea |

| C1.2. Interaction. | |||

| Index | English Question | Survey | Spanish Question |

| C1.2.1 | Interactivity in the class between classmates is very little | Q14.1 | La interactividad en la clase entre compañeros de clase es muy poca |

| C1.2.2 | Interaction in class with the teacher is very little | Q14.2 | La interacción en clase con el profesor es muy poca |

| C1.2.3 | It is very difficult to do group tasks | Q14.3 | Es muy difícil realizar tareas grupales |

| C1.2.4 | No spaces to interact with classmates | Q14.4 | No hay espacios para interactuar con los compañeros de clase |

| C1.2.5 | It is not possible to form study groups | Q14.5 | No es posible formar grupos de estudio |

| C1.2.6 | The interaction in a virtual class is less than in a face-to-face class | Q14.6 | La interacción en una clase virtual es menor que en una clase presencial |

| C.1.3. Assessment. | |||

| Index | English Question | Survey | Spanish Question |

| C1.3.1 | There is an academic overload for students in virtual classes | Q15.1 | Hay una sobrecarga académica para los alumnos en las clases virtuales |

| C1.3.2 | Exams are not suitable for online classes | Q15.2 | Los exámenes no son adecuados para clases en línea |

| C1.3.3 | There is no good feedback on the assignments | Q15.3 | No hay una buena retroalimentación de las tareas |

| C1.3.4 | There is no flexibility of teachers in terms of deadlines | Q15.4 | No hay flexibilidad de los profesores en los plazos de entrega |

| C1.3.5 | The quality of assignments and exams is lower in virtual classes | Q15.5 | La calidad de las tareas y exámenes es inferior en las clases virtuales |

- C2—Connectivity and Equipment

| Index | English Question | Survey | Spanish Question |

| C2.1 | I do not have (or have limited) access to the internet where I live | Q10.1 | No tengo acceso (o es limitado) al internet donde vivo |

| C2.2 | My internet speed is not adequate for my classes | Q10.2 | Mi velocidad de internet no es adecuada para mis clases |

| C2.3 | I do not have access (or it is rather limited) to a computer at home | Q10.3 | No tengo acceso (o es limitado) a un computador en mi vivienda |

| C2.4 | There are many technical problems while accessing classes or study material | Q10.4 | Hay muchos problemas técnicos durante el acceso a clases o material de estudio |

| C2.5 | My educational institution does not have the appropriate computer equipment (e.g., servers) for virtual teaching | Q10.5 | Mi institución educativa no tiene el equipo de cómputo (p. ej. servidores) adecuado para la enseñanza virtual |

- C3—Personal Issues

| C3.1. Physical Issues. | |||

| Index | English Question | Survey | Spanish Question |

| C3.1.1 | It is difficult to concentrate because there are many distractions such as cell phones, noises and interruptions from other people in the house | Q16.1 | Es difícil concentrarse porque hay muchas distracciones tales como celulares, ruidos e interrupciones de otras personas en la casa |

| C3.1.2 | Long hours in front of the computer cause back pain, vision and physical fatigue in general | Q16.2 | Largas horas frente al computador producen dolor de espalda, cansancio de visión y físico en general |

| C3.1.3 | It is difficult to accept the new virtual context | Q16.3 | Es difícil aceptar el nuevo contexto virtual |

| C3.1.4 | It is not easy to stay motivated in virtual classes | Q16.4 | No es fácil mantenerse motivados en las clases virtuales |

| C3.2. Health Concerns. | |||

| Index | English Question | Survey | Spanish Question |

| C3.2.1 | Quarantine is depressing | Q18.1 | La cuarentena es deprimente |

| C3.2.2 | I have not been able to carry out my medical examinations/treatment(s) | Q18.2 | No he podido llevar a cabo mis exámenes/tratamiento médico(s) |

| C3.2.3 | I am concerned about family/friends who have become ill | Q18.3 | Estoy preocupado por familiares/amigos que han enfermado |

| C3.3. Health Environment. | |||

| Index | English Question | Survey | Spanish Question |

| C3.3.1 | The school/university does not care about the mental health of the students | Q18.6 | A la escuela/universidad no les importa la salud mental de los estudiantes |

| C3.3.2 | Virtual classes do not provide recreation spaces | Q18.7 | Las clases virtuales no dan espacios de recreación |

| C3.3.3 | Virtual classes, in general, cause more stress than face-to-face classes | Q18.8 | Las clases virtuales, en general, causan másestrés que las presenciales |

| C3.4. Health Sadness. | |||

| Index | English Question | Survey | Spanish Question |

| C3.4.1 | I am sad for family/friends who have passed away | Q18.4 | Estoy preocupado por familiares/amigos que han enfermado |

| C3.4.2 | The school/university does not care about the mental health of the students | Q18.5 | Estoy triste por familiares/amigos que han fallecido |

- C4—Home Infrastructure and Study Environment.

| Index | English Question | Survey | Spanish Question |

| C4.1 | My home does not have adequate physical space for my virtual classes | Q12.1 | Mi vivienda no tiene espacio físico adecuado para mis clases virtuales |

| C4.2 | Activities of other people at home produce a lot of noise and interruptions | Q12.2 | Actividades de las demás personas en casa produce mucho ruido e interrupciones |

| C4.3 | I do not have adequate furniture at home (eg desk, chair) for my virtual classes | Q12.3 | No tengo el mobiliario adecuado en casa (p. ej. escritorio, silla) para mis clases virtuales |

| C4.4 | The physical infrastructure that one has at home for virtual classes is less than in the educational institution | Q12.4 | La infraestructura física que uno dispone en casa para las clases virtuales es menor que en la institución educativa |

- C5—Learning Platform and Access to Resources

| C5.1. Learning Platform. | |||

| Index | English Question | Survey | Spanish Question |

| C5.1.1 | The educational platform in use is not suitable for virtual instruction | Q11.1 | La plataforma educativa en uso no es adecuada para la instrucción virtual |

| C5.1.2 | Teachers do not know how to use the platform | Q11.2 | Los profesores no saben usar la plataforma |

| C5.1.3 | Students do not know how to use the platform | Q11.3 | Los alumnos no saben usar la plataforma |

| C5.1.4 | There is no information about the use of the platform | Q11.4 | No hay información acerca del uso de la plataforma |

| C5.2. Access to Resources. | |||

| Index | English Question | Survey | Spanish Question |

| C5.2.1 | Lack of access to library books is a severe limitation | Q11.5 | La falta de acceso a los libros de la biblioteca constituye una seria limitación |

| C5.2.2 | Lack of access to laboratories is a problem | Q11.6 | La falta de acceso a los laboratorios constituye un problema |

| C5.2.3 | It is necessary to have access to more study material (e.g., PPTs) in addition to the recordings of the class | Q11.7 | Hace falta tener acceso a más material de estudio (p. ej. PPTs) además de las grabaciones de la clase |

| C5.2.4 | Access to teaching resources is less in virtual instruction | Q11.8 | El acceso a recursos de enseñanza es menor en la instrucción virtual |

- C6—Financial Issues

| C6. Financial Issues. | |||

| Index | English Question | Survey | Spanish Question |

| C6.1 | I am worried about my financial situation | Q19.1 | Estoy preocupado por mi situacióneconómica |

| C6.2 | The economic situation of my family is uncertain | Q19.2 | La situacióneconómica de mi familia es incierta |

| C6.3 | I am not sure I will be able to continue studying, given the economic uncertainty | Q19.3 | No estoy seguro de poder continuar estudiando dada la incertidumbre económica |

| C6.4 | I think the costs associated with school/university are too high | Q19.4 | Pienso que los costos asociados a la escuela/universidad son muy altos |

- C7—University Administration and Costs

| C7.1. University Administration. | |||

| Index | English Question | Survey | Spanish Question |

| C7.1.1 | My university/school does not pay attention to the economic situation of the students | Q20.2 | Mi universidad/escuela no presta atención a la situacióneconómica de los estudiantes |

| C7.1.2 | Authorities and teachers have no leadership for the current transformation | Q20.3 | Autoridades y docentes no tienen liderazgo para la transformación actual |

| C7.2. University Costs. | |||

| Index | English Question | Survey | Spanish Question |

| C7.2.1 | Schools/universities that charge for tuition should lower prices because the facilities are not used | Q20.4 | Escuelas/universidades que cobran por la enseñanza deben bajar precios porque no se usan las instalaciones |

| C7.2.2 | In general, virtual classes require less cost from institutions than face-to-face classes | Q20.5 | En general, las clases virtuales demandan menos costos de las instituciones que las clases presenciales |

| 1 | The “Institute for Public Opinion” (IOP), currently Instituto for Social Analytics and Strategic Intelligence (PULSO), is an organization that polls public opinion as a way of conducting and supporting social research in the country. |

| 2 | The letter/number combination in brackets identifies the location of the quote within the dataset. |

| 3 | The qualitative part of the study was framed to discuss the problems students faced in their virtual instruction; however, for the survey questionnaire, a decision was made to frame the survey questions in terms of challenges or issues to avoid creating a response bias due to the negative connotation of the word “problems.” Therefore, for survey stages II and III, the terms financial issues, personal challenges, and so forth were used. |

| 4 | In this study, the terms category, thematic variable, challenge, construct, or variable are used interchangeably. The reason for using several different terms rather than a single one is an attempt to respect the names used in the different theoretical areas of survey research, composite indicators development, statistics, and MCDA. |

| 5 | A third, more dramatic—although less likely—possibility is that of self-selection; that is, those who were not able to solve their fundamental connectivity and equipment issues were not in the pool of online students who would answer the survey questions a few weeks later. It would be necessary to check the non-returning ratio of students for this purpose. |

| 6 | The data collection for this study was mainly among students from the largest private college in the country. |

| 7 | Values shown are only those above 0.4. |

| 8 | Q13-5 to Q13-7 were originally expected to be part of this group of C1.1 Quality of teaching but they were rather loaded into the group of C1.2 Class Interaction/Activities. However, in spite of being slightly above the lower threshold of 0.4, their impact was far lower than those of Q14.1 to Q14.6, and for this reason they were not included in the final list of C1.2 indicators. |

| 9 | The original score for each of the challenge dimensions/sub-dimension is obtained through an arithmetic averaging of all the response values of the questions corresponding to the specific challenge. For example, the score of C.1.1 Teaching is the average of the responses to the four questions from Q13.1 to Q13.4. |

| 10 | The present study was conducted in Spanish. A preliminary English translation of the questions is provided for your convenience, but the reader is advised to ensure it is adequate for the researcher’s needs. |

| 11 |

References

- Alavi, M.; Leidner, D.E. Research Commentary: Technology-Mediated Learning-Call for Greater Depth and Breadth of Research. Inf. Syst. Res. 2001, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eom, S.; Ashill, N. The Determinants of Students’ Perceived Learning Outcomes and Satisfaction in University Online Education: An Update. Decis. Sci. J. Innov. Educ. 2016, 14, 185–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnett, K.; Bonnici, L.J.; Miksa, S.D.; Kim, J. Frequency, Intensity and Topicality in Online Learning: An Exploration of the Interaction Dimensions That Contribute to Student Satisfaction in Online Learning. J. Educ. Libr. Inf. Sci. 2007, 48, 21–35. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, I. Building a theoretical framework of web-based instruction in the context of distance-education. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2001, 32, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.R. Distance Learning Environments Via World Wide Web, in Web-Based Instruction; Khan, B.H., Ed.; Educational Technology Publications: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, J.G. Assessing Online Learning; National Business Education Association: Reston, VA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Callister, R.R.; Love, M.S. A Comparison of Learning Outcomes in Skills-Based Courses: Online versus Face-to-Face Formats. Decis. Sci. J. Innov. Educ. 2016, 14, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parahoo, S.K.; Santally, M.I.; Rajabalee, Y.; Harvey, H.L. Designing a predictive model of student satisfaction in online learning. J. Mark. High. Educ. 2015, 26, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turoff, M. Alternative Futures for Distance Learning: The Force and the Darkside. In Proceedings of the UNESCO/OPEN UNIVERSITY International Colloquium: Virtual Learning Environments and the Role of the Teacher, Milton Keynes, UK, 27–29 April 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Olcott, D.J.; Wright, S.J. An institutional support framework for increasing faculty participation in postsecondary distance education. Am. J. Distance Educ. 1995, 9, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedró, J. COVID-19 y educación superior en América Latina y el Caribe: Efectos, impactos y recomendaciones políticas. Análisis Carol. 2020, 36, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, C.B.; Moore, S.; Lockee, B.B.; Trust, T.; Bond, M.A. The Difference between Emergency Remote Teaching and OnLine Learning. Educ. Rev. 2020. Available online: https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-difference-between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-online-learning (accessed on 4 August 2021).

- Whittle, C.; Tiwari, S.; Yan, S.; Williams, J. Emergency remote teaching environment: A conceptual framework for responsive online teaching crises. Inf. Learn. Sci. 2020, 121, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinoni, G.; Van’t Land, H.; Jensen, T. The Impact of COVID-19 in Higher Education Around the Worlds. In IAU Global Survey Report; International Association of Universities: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta, S.; Smita, M.K. The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Tertiary Education in Bangladesh: Students’ Perspectives. Open J. Soc. Sci. 2020, 8, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agaton, C.B.; Cueto, L.J. Learning at home: Parents’ lived experiences on distance learning during COVID-19 pandemic in the Philippines. Int. J. Eval. Res. Educ. 2021, 10, 901–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chunyan, Y. Online Teaching Self-Efficacy, Social–Emotional Learning (SEL) Competencies, and Compassion Fatigue Among Educators During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 50, 505–518. [Google Scholar]

- Morse, A.R.; Banfield, M.; Batterham, P.J.; Gulliver, A.; McCallum, S.; Cherbuin, N.; Farrer, L.M.; Calear, A.L. What could we do differently next time? Australian parents’ experiences of the short-term and long-term impacts of home schooling during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzankova, I.; Compare, C.; Marzana, D.; Guarino, A.; Napoli, I.D.; Rochira, A.; Calandri, E.; Barbieri, I.; Procentese, F.; Gatti, F.; et al. Emergency online school learning during COVID-19 lockdown: A qualitative study of adolescents’ experiences in Italy. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rekha, G. COVID-19: The Effects and Implications on Students Mental Health and Wellbeing. In Impact and Role of Digital Technologies in Adolescent Lives; Malik, S., Bansal, R., Tyagi, A.K., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Antonova, E.; Schlosser, K.; Pandey, R.; Kumari, V. Coping With COVID-19: Mindfulness-Based Approaches for Mitigating Mental Health Crisis. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 563417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozkurt, A.; Jung, I.; Xiao, J.; Vladimirschi, V.; Schuwer, R.; Egorov, G.; Lambert, S.; Al-Freih, M.; Pete, J.; Olcott, D., Jr.; et al. A global outlook to the interruption of education due to COVID-19 Pandemic: Navigating in a time of uncertainty and crisis. Asian J. Distance Educ. 2020, 15, 1–126. [Google Scholar]

- Carretero-Gómez, S.; Napierała, J.; Bessios, A.; Magi, E.; Pugacewicz, A.; Ranieri, M.; Triquet, K.; Lombaerts, K.; Bottcher, N.R.; Montanari, M.; et al. What did We Learn from Schooling Practices during the COVID-19 Lockdown; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Farris, D.G.; Kibbey, M.M.; Fedorenko, E.J.; Dibello, A.M. Qualitative Study of COVID-19 Distress in University Students. Emerg. Adulthood 2021, 9, 462–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Salgado, J.; Andrés-Villas, M.; Domínguez-Salas, S.; Díaz-Milanés, D.; Ruiz-Frutos, C. Related Health Factors of Psychological Distress During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Spain. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, A.; Jha, A.K.; Alat, P.; Das, S.S. Understanding coronaphobia. Asian J. Psychiatry 2020, 54, 102384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Morales, V.J.; Garrido-Moreno, A.; Martín-Rojas, R. The Transformation of Higher Education After the COVID Disruption: Emerging Challenges in an Online Learning Scenario. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 616059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, I.; Gupta, T.; Shree, A. Online teaching-learning in higher education during the lockdown period of COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 1, 100012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Govindarajan, V.; Srivastava, A. What the Shift to Virtual Learning Could Mean for the Future of Higher Education. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2020, 31, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Canaza-Choque, F.A. Educación superior en la cuarentena global: Disrupciones y transiciones. Rev. Digit. De Investig. En Docencia Univ. 2020, 14, e1315. Available online: http://www.scielo.org.pe/pdf/ridu/v14n2/2223-2516-ridu-14-02-e1315.pdf (accessed on 4 August 2021). [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.W.; Chen, R.N.; Liu, L.L.; Li, X.G.; Chen, J.B.; Tang, S.Y.; Zhao, J.B. The Impact of COVID-19 epidemic on Guangdong College students: The difference between seeking and not seeking psychological help. Front. Psychol. 2020. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33013582/ (accessed on 4 August 2021).

- Fülop, M.T.; Breaz, T.O.; He, X.; Ionescu, C.A.; Cordoş, G.S.; Stanescu, S.G. The role of universities’ sustainability, teachers’ wellbeing, and attitudes toward e-learning during COVID-19. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 981593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trust, T.; Whalen, J. Should Teachers be Trained in Emergency Remote Teaching? Lessons Learned from the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Technol. Teach. Educ. 2020, 28, 189–199. [Google Scholar]

- Cresswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis; SAGE Publications, Ltd.: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; Sage Publications Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Saaty, T.L. Decision Making for Leaders: The Analytic Hierarchy Process; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, E.; Cooper, O.; Peasley, M. Best Practices in Analytic Network Process Studies. Expert Syst. Appl. 2020, 159, 113536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freundenberg, M. Composite Indicators of Country Performance: A Critical Assessment. In OECD Science, Technology and Industry Working Papers; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD): Paris, France, 2003; Volume 16. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Handbook on Constructing Composite Indicators: Methodology and User Guide; OECD: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, E.; Stern, H. The City of Pittsburgh goes to the cloud: A case study of cloud strategic selection and deployment. J. Inf. Technol. Teach. Cases 2014, 4, 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. Theory and Applications of the Analytic Network Process; RWS Publications: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Leon, Y.L.; Mu, E. Organizational MIndfulness Assessment and Its Impact on Rational Decision Making. Mathematics 2021, 9, 1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L.; Peniwati, K. Group Decision Making: Drawing out and Reconciling Differences; RWS Publications: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, E.; Pereyra-Rojas, M. Practical Decision Making Using Super Decisions v3: An Introduction to the Analytic Hierarchy Process. In Springer Briefs in Operations Research; Springer International Publishing AG: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, R. A Survey of Composite Indices Measuring Country Performance: 2006 Update. 2009. Available online: https://www.eldis.org/document/A43097 (accessed on 4 August 2021).

- Saaty, T.L. Multicriteria Decision Making—The Analytic Hierarchy Process; Extended Edition; AHP Series; RWS Publications: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 1990; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Greco, S.; Ishizaka, A.; Tasiou, M.; Torrisi, G. On the Methodological Framework of Composite Indices: A Review of the Issues of Weighting, Aggregation, and Robustness. Soc. Indic. Res. 2019, 141, 61–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS, 3rd ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, J.P. Applied Multivariate Statistics for the Social Sciences, 4th ed.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Means, B.; Bakia, M.; Murphy, R. Learning Online: What Research Tells Us about Whether, When and How; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Network, S.E. Should Remote Teaching Sessions Be Shorter than Classroom Sessions? Academia Stack Exchange. 2022. Available online: https://academia.stackexchange.com/ (accessed on 4 August 2021).

- Ferri, F.; Grifoni, P.; Guzzo, T. Online Learning and Emergency Remote Teaching: Opportunities and Challenges in Emergency Situations. Societies 2020, 10, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J. Successes and Challenges: Teaching and Learning Chemistry in Higher Education in China in the Time of COVID-19. J. Chem. Educ. 2020, 97, 2810–2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonn, I.K.; Du Plessis, M.; Jansen Van Vuuren, C.D.; Marais, J.; Wagener, E.; Roman, N.V. Achievements and Challenges for Higher Education during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Rapid Review of Media in Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branch, R.M.; Dousay, T.A. Survey of Instructional Design Models, 5th ed.; Association for Educational Communications and Technology (AECT): Bloomington, IN, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Guncaga, J.; Lopuchova, J.; Ferdianova, V.; Zacek, M.; Ashimov, Y. Survey on Online Learning at Universities of Slovakia, Czech Republic and Kazakhstan during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. The COVID-19 Crisis Response: Supporting Tertiary Education for Continuity, Adaptation, and Innovation; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, R.M.; Abrami, P.C.; Borokhovski, E.; Wade, C.A.; Tamim, R.M.; Surkes, M.A.; Bethel, E.C. A Meta-Analysis of Three Types of Interaction Treatments in Distance Education. Rev. Educ. Res. 2009, 79, 243–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baran, E.; Alzoubi, D. Human-Centered Design as a Frame for Transition to Remote Teaching during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Technol. TEacher Educ. 2020, 28, 365–372. [Google Scholar]

- Bouton, B. Empathy research and teacher preparation: Benefits and obstacles. SRATE J. 2016, 25, 16–25. [Google Scholar]

- Portillo, S.; Pierra, L.I.C.; González, Ó.U.R.; Nogales, O.I.G. Enseñanza remota de emergencia ante la pandemia COVID-19 en Educación Media Superior y Educación Superior. Propósitos y Representaciones. Rev. De Psicol. Educ. 2020, 8, e589. [Google Scholar]

- Rosario-Rodríguez, A.; González-Rivera, J.A.; Cruz-Santos, A.; Rodríguez-Ríos, L. Demandas tecnológicas, académicas y psicológicas en estudiantes universitarios durante la pandemia por COVID-19. Rev. Caribeña De Psicol. 2020, 4, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falloon, G. From digital literacy to digital competence: The teacher digital competency (TDC) framework. Educ. Tech. Res. Dev. 2020, 68, 2449–2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quispe-Prieto, S.; Cavalcanti-Bandos, M.F.; Caipa-Ramos, M.; Paucar-Caceres, A.; Rojas-Jiménez, H.H. A Systemic Framework to Evaluate Student Satisfaction in Latin American Universities under the COVID-19 Pandemic. Systems 2021, 9, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, C.B.; Barbour, M.; Ferdig, R.E. A 2025 Vision for Building Access to K-12 Online and Blended Learning in Pre-service Teacher Education. J. Technol. Teach. Educ. 2022, 30, 201–216. [Google Scholar]

- MINEDU. Retorno a clases presenciales será en marzo del 2022 y al 100%. In El Peruano; Ministerio de Educación—MINEDU: Lima, Perú, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- MINEDU. Marco normativo para el retorno Seguro. In Resolución Ministerial N° 048-2022-MINEDU 2022; Ministerio de Educación: Lima, Perú, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- INEI. Informe Técnico: Estadísticas de Las Tecnologías de Información y Comunicación en Los Hogares; Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática: Lima, Perú, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- INEI. El 55.0% de Los Hogares del País Accedieron a Internet en el Tercer Trimestre del 2021; Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática: Lima, Perú, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Huanca-Arohuanca, J.; Supo-Condori, F.; Leon, R.S.; Quispe, L.A.S. El problema social de la educación virtual universitaria en tiempos de pandemia, Perú. Rev. Innov. Educ. 2020, 22, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degollación-Cox, A.P.; Rimac-Ventura, E. Teacher reflection on knowledge management in law teaching in times of COVID-19. Rev. Venez. De Gerenc. 2022, 27, 44–57. [Google Scholar]

- Aquino, O.F.; Zuta, P.M.; Cao, E.R. Remote teaching in professor training: Three Latin American experiences in times of COVID-19 pandemic. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huamán-Romaní, Y.L.; Estrada-Pantía, J.; Olivares-Rivera, O.; Rodas-Guizado, E.; Fuentes-Bernedo, F. Use of Technological Equipment for E-learning in Peruvian University Students in Times of Covid-19. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2021, 16, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovón, M.A.; Cisneros, S.A. Repercusiones de las clases virtuales en los estudiantes universitarios en el contexto de la cuarentena por COVID-19: El caso de la PUCP. Propósitos Y Represent. 2020, 8, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission; European Education and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA); Eurydice. The European Higher Education Area in 2020: Bologna Process Implementation Report; European Commission, European Education and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA), Eurydice, Eds.; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Florek-Pazkowska, A. Wielokryterialne Problemy Decyzyjne W Proekologicznych Działaniach Produktowych Przedsiębiorstw in Działania Ekologiczne W Polityce Produktowej Przedsiębiorstw; Adamczyk, W., Ed.; Akapit: Toruń, Poland, 2013; pp. 121–141. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, E.; Pereyra-Rojas, M. Toma de Decisiones Prácticas: Una Introducción al Proceso Jerárquico Analítico (AHP) Usando SuperDecisions v2 y v3; MPR Trade: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

| Demographics | Characteristics | No | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Less than 20 years old | 15 | 30% |

| 21–24 years old | 25 | 50% | |

| 25–29 years old | 4 | 8% | |

| More/egual 30 years old | 6 | 12% | |

| Gender | Female | 32 | 64% |

| Male | 18 | 36% | |

| Discipline | Administration | 5 | 10% |

| Economy | 3 | 6% | |

| Engineering | 1 | 2% | |

| Others | 41 | 82% |

| Demographics | Characteristics | No | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Less than 20 years old | 1 | 0.63% |

| 25–29 years old | 25 | 15% | |

| 30–34 years old | 45 | 27.5% | |

| Gender | More than 34 years old | 94 | 57% |

| Male | 104 | 64% | |

| Female | 54 | 36% |

| Theme Code | Themes | Count | % Count |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | Internet connectivity and lack of equipment by students Internet connectivity and lack of equipment by Hi-Ed institutions | 99 | 20% |

| 150 | 11 | 2% | |

| 201 | Inadequate physical facilities to study (e.g., study in bed) Inadequate environment to study (e.g., constant interruptions) | 55 | 11% |

| 203 | 29 | 6% | |

| 300 | Learning Platform (e.g., too cumbersome) | 14 | 3% |

| 400 | Quality of Teaching (e.g., teachers untrained for virtual education) Exams (e.g., not enough time) | 96 | 19% |

| 500 | 6 | 1% | |

| 600 | Access to Resources (e.g., library books) | 22 | 4% |

| 700 | Lack of class interaction with students and teachers | 26 | 5% |

| 800 | Personal Problems (e.g., physical exhaustion, lack of focus) | 47 | 9% |

| 850 | Financial problems (student) | 6 | 1% |

| 900 | Personal Organization Problems Mental Health | 23 | 5% |

| 1000 | 28 | 6% | |

| 1100 | University Admin University Costs | 4 | 1% |

| 1200 | 9 | 2% | |

| 1300 | Financial problems (family) | 20 | 4% |

| Grand Total | 495 | 100% | |

| 600 | Access to Resources |

| 601 | Lack of access to libraries |

| 602 | Presentations are needed in addition to videos |

| 603 | Insufficient study material |

| 604 | lack of access to laboratories |

| 605 | Lack of access to class resources due to lack of programs |

| 606 | Lack of access to needed services (e.g., printing) |

| 607 | Lack of access to the specific course material (e.g., design) |

| ID | Theme Codes | Challenge Categories | Count | % Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | 400/500/700 | Quality of Virtual Instruction | 128 | 26% |

| C2 | 100/150 | Connectivity &Equipment | 110 | 22% |

| C3 | 800/900/1000 | Personal Issues | 98 | 20% |

| C4 | 200 | Home Infrastructure & Study Environment | 84 | 17% |

| C5 | 300/600 | Learning Platform & Access to Resources | 36 | 7% |

| C6 | 850/1300 | Financial Problems | 26 | 5% |

| C7 | 1100/1200 | University Admin &Costs | 13 | 3% |

| Grand Total | 495 | 1 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | # | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Items | Alpha | Mean | SD | C1.1 | C1.2 | C1.3 | C2 | C3.1 | C3.2 | C3.3 | C3.4 | C4 | C5.1 | C5.2 | C6 | C7.1 | C7.2 | ||

| 1 | C1.1. | QUALITY | 4 | 0.841 | 1.787 | 0.916 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 2 | C1.2. | INTERACTION | 9 | 0.914 | 2.780 | 1.106 | 0.622 ** | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 3 | C1.3. | ASSESSMENT | 5 | 0.817 | 2.528 | 0.983 | 0.571 ** | 0.714 ** | 1 | |||||||||||

| 4 | C2. | EQUIPMENT | 5 | 0.791 | 1.630 | 0.784 | 0.248 ** | 0.174 | 0.205 * | 1 | ||||||||||

| 5 | C3.1 | PERSONAL | 6 | 0.834 | 3.154 | 1.019 | 0.528 ** | 0.691 ** | 0.619 ** | 0.239 * | 1 | |||||||||

| 6 | C3.2 | MENTAL CONCERNS | 3 | 0.730 | 3.061 | 1.061 | 0.277 ** | 0.404 ** | 0.387 ** | 0.267 ** | 0.339 ** | 1 | ||||||||

| 7 | C3.3 | MENTAL ENVIRONMT | 3 | 0.725 | 2.769 | 1.059 | 0.460 ** | 0.507 ** | 0.635 ** | 0.068 | 0.550 ** | 0.344 * | 1 | |||||||

| 8 | C3.4 | MENTAL SADNESS | 2 | 0.720 | 3.535 | 1.136 | 0.077 | 0.053 | 0.119 | 0.134 | 0.084 | 0.421 ** | 0.091 | 1 | ||||||

| 9 | C4 | HOME INFRASTR. | 4 | 0.845 | 2.577 | 1.201 | 0.555 ** | 0.482 ** | 0.440 ** | 0.358 ** | 0.604 ** | 0.172 | 0.410 ** | 0.057 | 1 | |||||

| 10 | C5.1 | LEARNING PLATFORM | 4 | 0.722 | 1.702 | 0.731 | 0.662 ** | 0.425 ** | 0.373 ** | 0.470 ** | 0.380 ** | 0.346 ** | 0.276 ** | 0.129 | 0.471 ** | 1 | ||||

| 11 | C5.2 | ACCESS TO RESOURCES | 4 | 0.815 | 2.715 | 1.128 | 0.557 ** | 0.590 ** | 0.547 ** | 0.261 ** | 0.505 ** | 0.328 ** | 0.387 ** | 0.072 | 0.466 ** | 0.492 ** | 1 | |||

| 12 | C6 | FINANCIALS | 4 | 0.817 | 2.915 | 1.019 | 0.229 * | 0.379 ** | 0.385 ** | 0.366 ** | 0.306 ** | 0.401 ** | 0.260 ** | 0.223 * | 0.297 ** | 0.214 * | 0.302 ** | 1 | ||

| 13 | C7.1 | UNIVERSITY ADMIN | 2 | 0.717 | 2.398 | 1.067 | 0.536 ** | 0.498 ** | 0.603 ** | 0.13 | 0.388 ** | 0.337 ** | 0.472 ** | 0.147 | 0.317 ** | 0.369 ** | 0.499 ** | 0.365 ** | 1 | |

| 14 | C7.2. | UNIVERSITY COSTS | 2 | 0.819 | 4.040 | 1.091 | 0.181 | 0.289 ** | 0.225 * | 0.062 | 0.311 ** | 0.311 ** | 0.215 * | 0.213 * | 0.14 | 0.266 ** | 0.318 ** | 0.308 ** | 0.269 ** | 1 |

| Challenge ID | Description | Challenge Rank * Phase I | Importance Priority Phase II | Priority Rank ** Phase II |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | Perceived quality of instruction/learning | 1 | 0.0679 | 6 |

| C2 | Poor Internet connectivity and lack of proper equipment | 2 | 0.0882 | 4 |

| C3 | Personal and psychological issues | 3 | 0.0668 | 7 |

| C4 | Lack of appropriate home infrastructure | 4 | 0.2088 | 2 |

| C5 | Learning platform and access to resources | 5 | 0.2900 | 1 |

| C6 | Financial issues related to students and families | 6 | 0.2087 | 3 |

| C7 | General concerns related to the university and others | 7 | 0.0696 | 5 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mu, E.; Florek-Paszkowska, A.; Pereyra-Rojas, M. Development of a Framework to Assess Challenges to Virtual Education in an Emergency Remote Teaching Environment: A Developing Country Student Perspective—The Case of Peru. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 704. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12100704

Mu E, Florek-Paszkowska A, Pereyra-Rojas M. Development of a Framework to Assess Challenges to Virtual Education in an Emergency Remote Teaching Environment: A Developing Country Student Perspective—The Case of Peru. Education Sciences. 2022; 12(10):704. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12100704

Chicago/Turabian StyleMu, Enrique, Anna Florek-Paszkowska, and Milagros Pereyra-Rojas. 2022. "Development of a Framework to Assess Challenges to Virtual Education in an Emergency Remote Teaching Environment: A Developing Country Student Perspective—The Case of Peru" Education Sciences 12, no. 10: 704. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12100704

APA StyleMu, E., Florek-Paszkowska, A., & Pereyra-Rojas, M. (2022). Development of a Framework to Assess Challenges to Virtual Education in an Emergency Remote Teaching Environment: A Developing Country Student Perspective—The Case of Peru. Education Sciences, 12(10), 704. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12100704