Analysis of the Perceptions Shared by Young People about the Relevance and Versatility of Religion in Culturally Diverse Contexts

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- To describe the relevance of the teaching of religion for young people within the educational system and in the immediate peer context.

- To identify the relationships between the versatility of religion and the beliefs or sense of belonging to a religious community for the young population.

- To determine the presence of significant differences in the perception of other people or other religious beliefs or cosmovisions in relation to the “gender” and “years of religion studies” variables.

2.1. Research Design

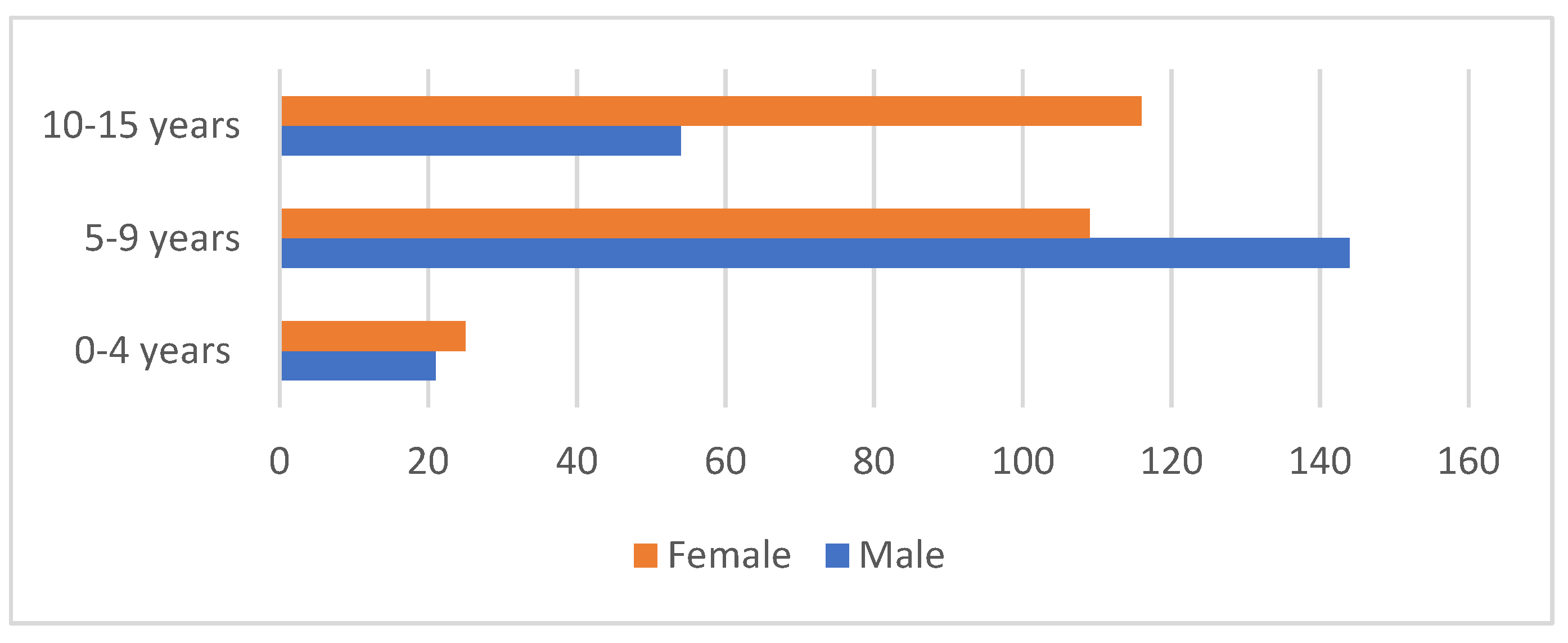

2.2. Participants

3. Results

3.1. How Learning about Religions Helps Young People

3.2. Young People’s Stance towards Religion

- Factor 1: Relevance of religion (RR). This factor groups the highest number of items: a total of four (41, 43, 44 and 45). It includes items that refer to the importance of religion at the internal and personal level, as well as to its historical value.

- Factor 2: Versatility of religion (VR). It groups a total of two items (46 and 47). Both refer to the changing processes of religion, in terms of beliefs and a sense of belonging to a religious community.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Kant argues that the purpose of Nature is harmony and peace, regardless and independently of what human beings think and want. […] Whether by «chance» or by «providence» of a higher cause that directs Humanity, it always resorts to the mechanisms and tricks needed to lead human beings towards coexistence.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nisa Ávila, J. Análisis comparado del principio de libertad religiosa, Islam y educación en la Unión Europea y el ordenamiento jurídico de sus estados miembros. Rev. De Educ. Y Derecho Educ. Law Rev. 2018, 18, 1–23. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6680361 (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- Koukounaras-Liagkis, M. Religion and Religious Diversity within Education in a Social Pedagogical Context in Times of Crisis: Can Religious Education Contribute to Community Cohesion? Int. J. Soc. Pedagog.–Spec. Issue ‘Soc. Pedagog. Times Crisis Greece’ 2015, 4, 85–100. Available online: http://www.internationaljournalofsocialpedagogy.com (accessed on 24 June 2022). [CrossRef]

- Kogan, I.; Fong, E.; Reitz, J. Religion and integration among immigrant and minority youth. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2020, 46, 3543–3558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, J. Diversity and Citizenship Education in Multicultural Nations. Multicult. Educ. Rev. 2009, 1, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedone, C. Las representaciones sociales en torno a la inmigración ecuatoriana a España. Íconos-Rev. De Cienc. Soc. 2002, 14, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, M.; Pueyo, S. El aula, mosaico de culturas. Carabela 2003, 54, 59–70. Available online: https://cvc.cervantes.es/ensenanza/biblioteca_ele/carabela/pdf/54/54_059.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- Álvarez, J.L.; González., H.; Fernández., G. El conflicto cultural y religioso. Aproximación etiológica. In Dioses en las Aulas; Álvarez, J.L., Essomba, M., Eds.; Graó: Barcelona, Spain, 2012; pp. 23–59. [Google Scholar]

- Johannessen, O.; Skeie., G. The relationship between religious education and intercultural education. Intercult. Educ. 2019, 30, 260–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarrete, J.; Vásquez, A.; Monter, E.; Cantero, D. Significant learning in catholic religious education: The case of Temuco. Br. J. Relig. Educ. 2020, 42, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edara, I. Religion: A Subset of Culture and an Expression of Spirituality. Adv. Anthropol. 2017, 7, 273–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, P.E.; Yoo, Y.; Vaughn, J.M.; Tirrell, J.M.; Geldhof, G.J.; Iraheta, G.; Williams, K.; Sim, A.; Stephenson, P.; Dowling, E.; et al. Evaluating the measure of diverse adolescent spirituality in samples of Mexican and Salvadoran youth. Psychol. Relig. Spirit. 2021, 13, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnitker, S.; King, P.; Houltberg, B. Religion, spirituality, and thriving: Transcendent narrative, virtue, and telos. J. Res. Adolesc. 2019, 29, 276–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stronge, S.; Bulbulia, J.; Davis, D.; Sibley, C. Religion and the development of character: Personality changes before and after religious conversion and deconversion. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2020, 12, 801–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, E. Spirituality and the temporal dynamics of transcendental positive emotions. Psychol. Relig. Spirit. 2017, 9, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCamp, W.; Smith, J. Religion, nonreligion, and deviance: Com-paring faiths and family’s relative strength in promoting social conformity. J. Relig. Health 2019, 58, 206–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estrada, C.; Lomboy, M.; Gregorio, E.; Amalia, E.; Leynes, C.; Quizon, R.; Kobayashi, J. Religious education can contribute to adolescent mental health in school settings. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2019, 13, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, C.; Brieant, A.; King-Casas, B.; Kim-Spoon, J. How Is Religiousness Associated with Adolescent Risk-Taking? The Roles of Emotion Regulation and Executive Function. J. Res. Adolesc. 2019, 29, 334–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purwono, U.; French, D.; Eisenberg, N.; Sharon, C. Religiosity and Effortful Control as Predictors of Antisocial Behaviour in Muslim Indonesian Adolescents: Moderation and Mediation Models. Psychol. Relig. Spirit. 2018, 11, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hin, C.; Kennedy, K.; Hung, C.; Ming Tak, M. Religious engagement and attitudes to the role of religion in society: Their effect on civic and social values in an Asian context. Br. J. Relig. Educ. 2018, 40, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepperd, J.; Pogge, G.; Lipsey, N.; Smith, C.; Miller, W. The link between religiousness and prejudice: Testing competing explanations in an adolescent sample. Psychol. Relig. Spirit. 2019, 13, 358–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moberg, M.; Sjö, S.; Kwaku, B.W.; Erdis, H.; Fernández, R.; Castillo Cárdenas, S.; Benyah, F.; Villacrez, M. From socialization to self-socialization? Exploring the role of digital media in the religious lives of young adults in Ghana, Turkey, and Peru. Religion 2019, 49, 240–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durkheim, E. Las Formas Elementales de la Vida Religiosa; Adiciones Akal: Madrid, Spain, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, P. The Many Altars of Modernity: Toward a Paradigm for Religion in a Pluralist Age; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- King, P.; Furrow, J. Religion as a resource for positive youth development: Religion, social capital, and moral outcomes. Psychol. Relig. Spirit. 2008, 58, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breskaya, O.; Botvar, P. Views on religious freedom among young people in Belarus and Norway: Similarities and contrasts. Religions 2019, 10, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmos-Gómez, M.C.; López-Cordero, R.; García-Segura, S.; Ruiz-Garzón, F. Adolescents’ Perception of Religious Education According to Religion and Gender in Spain. Religions 2020, 11, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Segura, S.; Martínez-Carmona, M.J.; Gil del Pino, C. Estudio descriptivo de la educación religiosa de estudiantes de secundaria de la provincia de Córdoba (España). Rev. De Hum. 2020, 40, 178–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Pearce, L. Understanding Why Religious Involvement’s Relationship with Education Varies by Social Class. J. Res. Adolesc. 2019, 29, 369–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, R. Religious Education for Plural Societies: The Selected Works of Robert Jackson; World Library of Educationalists Series; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Matemba, Y.; Addai-Mununkum, R. These religions are no good–they’re nothing but idol worship’: Mis/representation of religion in Religious Education at school in Malawi and Ghana. Br. J. Relig. Educ. 2017, 41, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban Garcés, C. Renovar la didáctica de la religión inspirados en la pedagogía de la interioridad. Educ. Y Futuro Rev. De Investig. Apl. Y Exp. Educ. 2020, 43, 17–47. Available online: https://cesdonbosco.com/documentos/revistaeyf/EYF_43.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2022).

- Bertram-Troost, G.; Schihalejev, O.; Neill, S. Religious diversity in society and school: Pupils’ perspectives on religion, religious tolerance and religious education: An introduction to the REDCo research network. Relig. Educ. J. Aust. 2014, 30, 17–23. Available online: https://search.informit.com.au/documentSummary;dn=249207174213032;res=IELHSS (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Dietz, G.; Rosón Lorente, J.; Ruiz Garzón, F. Homogeneidad confesional en tiempos de pluralismo religioso. Rev. CPU-E Rev. De Investig. Educ. 2011, 13, 1–42. Available online: http://www.uv.mx/cpue/num13/inves/Dietz_homogeneidadcon-fesional.html (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Jackson, R. Religion, Education, Dialogue and Conflict. Perspectives on Religious Education Research; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- GEMRIP. Hacia una Educación Interreligiosa e Intercultural en la Escuela. Documento de trabajo, Grupo de Estudios Multidiciplinarios Sobre Religión e Incidencia Pública. 2019. Available online: https://www.otroscruces.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Documento-FINAL-Hacia-una-edicaci%C3%B3n-religiosa.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Baeza, J.; Aparicio, R. Young People’s Reality. Educational Challenges; Librería Editrice: Vatican, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Schachter, E.; Ben Hur, A. The Varieties of Religious Significance: An Idiographic Approach to Study Religion’s Role in Adolescent Development. J. Res. Adolesc. 2019, 29, 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, S.; Nelson, J.; Moore, J.; King, P. Processes of Religious and Spiritual Influence in Adolescence: A Systematic Review of 30 Years of Research. J. Res. Adolesc. 2019, 29, 241–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, P. Beyond Passive Acceptance: Openness to Transformation by the Other in a Political Philosophy of Pluralism. In Identity and Pluralism: Ethnicity, Religion and Values; Collste, G., Ed.; Centre for Applied Etichs, Liköpings Universitet: Linköpin, Sweden, 2010; pp. 61–78. [Google Scholar]

- Breskaya, O.; Francis, L.; Giordan, G. Perceptions of the Functions of Religion and Attitude toward Religious Freedom: Introducing the New Indices of the Functions of Religion (NIFoR). Religions 2020, 11, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brettschneider, C. A transformative theory of religious freedom: Promoting the reasons for rights. Political Theory 2010, 38, 187–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnitker, S.; Williams, E.; Medenwaldt, J. Personality and Social Psychology Approaches to Religious and Spiritual Development in Adolescents. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2021, 6, 289–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buelvas, J. Relevancia de la religión y la ciencia en la perspectiva de la racionalidad científico-técnica contemporánea. In Ciencia y religión: Horizontes de Relación desde el Contexto Latinoamericano; Bonilla, J., Ed.; Universidad de San Buenaventura: Bogotá, Colombia, 2012; pp. 223–236. [Google Scholar]

- Cifuentes, L. Reflexiones sobre la paz perpetua. Paideia. Rev. De Filos. Y Didáctica Filosófica 2005, 26, 261–273. [Google Scholar]

- Cordero, R.; Ruiz, F.; Medina, L.; Olmos-Gómez, M.C. Religion: Interrelationships and Opinions in Children and Adolescents. Interaction between Age and Beliefs. Religions 2021, 12, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla, J. La teología al encuentro del pensamiento complejo. Perspectivas para el diálogo entre las ciencias y la teología. In Ciencia y Religión: Horizontes de Relación desde el Contexto Latinoamericano; Bonilla, J., Ed.; Universidad de San Buenaventura: Bogotá, Colombia, 2012; pp. 52–68. [Google Scholar]

| How Learning about Religions (LR) at School Helps | M | SD | N |

|---|---|---|---|

| 16. Understanding the others in order for a peaceful coexistence | 2.02 | 1.01 | 385 |

| 17. Understanding history | 2.23 | 1.08 | 385 |

| 18. Gaining a better understanding of reality | 2.38 | 1.09 | 385 |

| 19. Developing my own point of view | 2.12 | 1.04 | 385 |

| 20. Developing moral values | 2.24 | 1.05 | 385 |

| 21. Learning about my own religion | 2.08 | 1.10 | 385 |

| Total | 2.18 | 0.80 | 385 |

| Attitudes If Young People towards Religion | Factors | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | |

| 41. Religion helps me face difficulties | 0.842 | −0.020 |

| 44. Religion determines my whole life | 0.750 | −0.112 |

| 45. Religion is important in the history of our country | 0.690 | 0.201 |

| 43. Religion makes sense | 0.689 | −0.059 |

| 46. You can be a religious person without belonging to any religious community | −0.108 | 0.764 |

| 47. My beliefs about religion can change | 0.090 | 0.753 |

| Explained variance | 37.35 | 20.13 |

| Factor 1: Relevance of Religion (RR) | M | SD | N |

|---|---|---|---|

| Religion helps me face difficulties | 2.87 | 1.13 | 385 |

| I respect believers | 1.62 | 0.96 | 385 |

| Religion makes no sense | 3.63 | 1.13 | 385 |

| Religion determines my whole life | 3.53 | 1.13 | 385 |

| Religion is important in the history of our country | 2.45 | 1.06 | 385 |

| You can be a religious person without belonging to any religious community | 2.23 | 1.05 | 385 |

| My beliefs about religion can change | 2.81 | 1.09 | 385 |

| Total | 2.80 | 0.83 | 385 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

García-Segura, S.; Martínez-Carmona, M.-J.; Gil-Pino, C. Analysis of the Perceptions Shared by Young People about the Relevance and Versatility of Religion in Culturally Diverse Contexts. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 667. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12100667

García-Segura S, Martínez-Carmona M-J, Gil-Pino C. Analysis of the Perceptions Shared by Young People about the Relevance and Versatility of Religion in Culturally Diverse Contexts. Education Sciences. 2022; 12(10):667. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12100667

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía-Segura, Sonia, María-José Martínez-Carmona, and Carmen Gil-Pino. 2022. "Analysis of the Perceptions Shared by Young People about the Relevance and Versatility of Religion in Culturally Diverse Contexts" Education Sciences 12, no. 10: 667. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12100667

APA StyleGarcía-Segura, S., Martínez-Carmona, M.-J., & Gil-Pino, C. (2022). Analysis of the Perceptions Shared by Young People about the Relevance and Versatility of Religion in Culturally Diverse Contexts. Education Sciences, 12(10), 667. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12100667