Abstract

The starting point (1) of our proposal is the observation of the lack of intercultural practices in schools in France, even in the crucial context of teaching French to migrant children (2). Thanks to previous studies, we, therefore, develop theoretical anchors (3) about learning territories, the ways to recycle language, and cultural experiences that can encompass all the context parameters (a pan-language approach) to elaborate an intercultural model for learning and teaching. The aim is to propose, methodological reflections to offer a model which could help change the representations and practices of the educational community regarding multilingualism so that students’ language and cultural experiences could become an asset to achieve academic success (4). It leads to a discussion about leads to the creation of the intercultural language diamond model to teach and learn (through) languages (5). Projects based on the language model give the opportunity to discuss this proposal (5): interests and possible limitations (6). The conclusion (7) pledges the use of the language diamond to counterbalance the ideology which considers diversity as an issue, and therefore adopt a holistic, maximalist point of view: a pan-language and pan-cultural approach to encompass the complexity of education challenges today.

1. Introduction. Teaching Languages and Cultures: Recurrent Practices of Ideological Dominance

A perhaps new idea under the intercultural sun would be to propose an intercultural model of reflection on languages and cultures that allow their teaching and learning to overcome current forms of ideological dominations [1]. Indeed, numerous studies [2,3] show that, counter-intuitively, teaching languages does not always imply an openness to the other, an intercultural approach. On the contrary, this teaching can often convey numerous stereotypes in the discourses of teachers, learners [4], educational policies [5], and the teaching materials themselves [6]. Forms of hierarchy between languages can appear at various levels such as policy makers, schools, classrooms, and even among students’ parents. Pedagogical practices thus often validate the discourses of domination without being challenged. The school, which should be a bastion of interculturality, a place for reflection on the other and oneself, on history, forms of domination, and their possible resolutions, paradoxically becomes the place of social reproduction and inequalities [7]. Indeed, while many projects have emerged, both at the macro-institutional level (e.g., social justice (The United Nations’ 2006 document Social Justice in an Open World: The Role of the United Nations), intercultural encounters in Europe (https://www.coe.int/en/web/autobiography-intercultural-encounters, URL, accessed on 27 April 2023), global competence (https://www.oecd.org/pisa/innovation/global-competence/, URL, accessed on 27 April 2023), decoloniality [8] and in class-based initiatives), the results are very uneven if we simply consider the rise of nationalist political parties [9]. This finding calls into question whether education is ready to support both teachers and students in their quest for including intercultural dimensions in their teaching today. It is therefore in response to these challenges that the intercultural model of the language diamond was conceived, in an attempt to make a difference, humbly, from examples taken from the French context on the teaching-learning of languages and cultures today which includes reflection on the political, ideological, and multilingual levels from an intercultural perspective.

Thus, we will first return to the link between language teaching/learning and interculturality using the iconic example of teaching French to migrant children in France. This situation allows us to point out the intercultural difficulties facing the educational staff. After theoretical considerations regarding the importance to consider each student’s learning territory, linking formal, informal, and non-formal ways of a living language and cultural experiences, recycling these experiences can be an interesting element of the discussion to elaborate an intercultural model to teach and learn (through) languages. As a result, an intercultural model called the “language diamond” which has seven facets is proposed. It aims to recognize the diversity and the ever-changing complexity of each individual, the use of language [10], and cultural experiences in the classroom as a resource for teaching and learning. It focuses on teaching and learning with multilingual and multicultural materials, the implementation of mutual mentoring, and the use of multilingual and multicultural environments outside the classroom. The inclusion of parents and the sensitization of educational staff and teachers of all disciplines to the principles underpinning intercultural approaches are encompassed in the model. Projects in primary, secondary, and kindergarten illustrate and offer a discussion on the sustainability of the model. The conclusion summarizes what we call a pan-language and pan-cultural philosophy, which places at the heart of its reflection the question of recycling language and cultural experiences to teach and learn (through) languages.

2. About the French School Context: Little Interculturality under the Sun

“No content can be separated from its scientific production. This is called epistemology” [11]. That is why it is interesting to start with an anecdote related to personal scientific history.

While I had just finished a thesis (2000, published in a book form in Auger 2007 [6]) on clichés in French as a foreign language textbooks in Europe by adopting an intercultural perspective to analyze stereotyped discourses, a “Centre for the welcoming of newly-arrived and traveling children”, under the authority of the French Ministry of Education, asked me to work on “intercultural problems” generated by these migrant children. Classroom observations seeking potential “intercultural problems” to overcome [12] and interviews with teachers revealed that they had very little intercultural knowledge and categorized pupils and their productions very frequently. Intercultural approaches are hardly integrated with teachers’ training programs except in the FLE (French as a foreign language) degree course, which has made them compulsory since 1984. During the teachers’ interviews, when we asked what practitioners knew or understood by “intercultural pedagogy”, we were told with a smile “you mean couscous pedagogy?”. In response to our astonishment, the trainers explained that intercultural work was often limited to one day based on the cultural traditions (“couscous, mint tea, Berber tent…”) of the migrant children’s families. It is therefore clear that the intercultural approach that advocates a cross-sectional view [13] and genuine interaction merely bears the hallmarks of cultural folklore, which may reinforce stereotypes. Abdallah-Pretceille [14] notes the ambiguities and even the dangers of the distinction between difference and universality: a moralization of the perception of differences, an interpretation of the difference in terms of the deficit, a radicalization of differences, a fossilization through decontextualization (i.e., a sanitization that drifts towards exoticism), an explanatory and justifying value of differences that ratifies positions of rejection, of domination through an apparent rationalization, a hierarchical and unequal perspective: “the hypertrophy of difference hides a form of condescension and a form of social ranking” ([14], p. 9).

Despite this scientific research and European pedagogical recommendations (The Council of Europ Committee of Ministers published a recommendation (CM/Rec 2022) to member States on the importance of plurilingual and intercultural education for a culture of democracy (adopted by the Committee of Ministers on 2 February 2022, at the 1423rd meeting of the Ministers’ Deputies)), teachers in France are not systematically trained about these theoretical and practical issues [15], even though some classes in various neighborhoods are sometimes totally or largely multilingual (in UPE2A, Pedagogical Unit for newly arrived Allophone students (Allophone (instead of plurilingual)) is the term chosen by the Ministry of Education and show the focus on otherness instead of the language biography), but also in ordinary classes). Furthermore, the linguistic ideologies shared in France are still marked by glottophobia [16], envisaging the hexagon as a monolingual country [16] despite the two hundred languages present on its territory (Ministry of culture, 2016), including extra-marine territories. The representation of French as a quality language is a very prevalent ideology [17], especially among teachers. Indeed, the linguistically unifying aspects of school, as well as its repressive aspect [16] towards other languages of France, including regional languages, but also the languages of migration in the history of education in France, have a strong impact on these perceptions of family languages.

Many French studies [18,19] show that migrant pupils are only rarely considered as bilingual or plurilingual (In our view, every pupil is plurilingual sinceother languages are taught in schools, in addition to the many regional, family, and migrant languages). The bilingual student is too often associated with a balanced knowledge of the two languages, both spoken and written, and equated with a native speaker, without interference between the two languages. In reality, bi-plurilingualism is the ability to use different languages in real communication situations, and proficiency is assessed by the ability to make oneself understood, and this can vary. Furthermore, it appears that social actors refer to language and culture learning as a juxtaposition of homogeneous and monolithic languages and cultures. This representation does not reflect the reality of bi-pluri/lingual practices, which includes alternating codes, borrowings, word games, and varied cultural elements.

“Stop speaking Arabic in the courtyard”, “their phone texting makes them make mistakes in writing”, “they should try to speak French at home”, “my good resolution for the new year: not to speak Wolof in class”, “speak correctly”, “what a poor command of French”, “young people speak increasingly poorly, especially in the disadvantaged neighborhoods”, “these languages are aggressive”… For the past 20 years, using discourse analysis to identify language and cultural representations and practices in French schools that could help considering them as resources to teach and learn (for instance Comparing our Languages (https://www.ecml.at/ECML-Programme/Programme2008–2011/Majoritylanguageinmultilingualsettings/Trainingkit/tabid/5452/language/en-GB/Default.aspx, accessed on 27 April 2023), Maledive (https://maledive.ecml.at/ Accessed on 27 April 2023), Romtels (https://research.ncl.ac.uk/romtels/ Accessed on 27 April 2023) projects) we have been recording these ordinary remarks by teachers and pupils, which bear witness to the stereotypes circulating in the school context and, more widely, in the media [16]. However, how can we think otherwise when we are trained in a pedagogical approach to monolingualism and homogeneity, as if languages and the languages of speech were watertight, as if we never changed the elements of our lexicon, syntax, prosody, etc., according to the situations and the people we interact with, whether orally or in writing. The same goes for our social experiences. Indeed languages and cultures are the sums of these variations. This is an exciting game for those who want to play with them. Moving from one variation to another, understanding the challenges of the different contexts in a pedagogy of the gap, of plurilingualism and interculturality is dynamic and matches the reality of our multilingual classrooms with their multiple identities.

Categorizing the other person, his/her language practices, and his/her school performance probably allows us to avoid an understandable emotional overload: how can we get him/her to adopt the school language and culture? This observation leads us to draw on considerations in order to deconstruct these perceptions, by identifying, being aware of the abusive links between perceptions and behaviors, and finding new practices to prevent them from being harmful, which is developed, for instance, in Dervin’s work [5].

Representing family languages and cultures or the skills and experiences of students and their parents as irrelevant resources for classroom activities is ultimately stigmatizing. Such representations and classroom practices that ignore or stigmatize the other are contrary to the perspectives adopted by the work on interculturality [2]. Projects have been carried out in France and abroad to remedy these representations by proposing theoretical and practical content for teachers (SIRIUS https://siriusfrance.jimdofree.com/; https://www.sirius-migrationeducation.org/sirius-project/, accessed on 27 April 2023), LISTIAC (https://listiac.univ-montp3.fr/; https://listiac.org/, accessed on 27 April 2023), I am plurilingual (http://www.iamplurilingual.com/), Conbat+ (https://conbat.ecml.at/Theproject/tabid/246/language/en-GB/Default.aspx, accessed on 27 April 2023), LGIDF (https://lgidf.cnrs.fr/, accessed on 27 April 2023), etc.). These projects aim to work on these representations so that the diverse languages and cultural experiences, in fact, the whole backgrounds of pupils are no longer considered as the symptom of an otherness, which is considered as deficient, useless, or disturbing, particularly for learning.

Other representations of a more political aspect are also involved in the difficulty of welcoming family languages and cultures into the classroom when some relate to a fear of communitarianism and separatism on the part of pupils who are capable of speaking other languages or having different cultural experiences from those of the school. These ‘arguments’ are rooted in the way the French Republic has been constructed promoting discretion about “private matters” regarding religion or languages. This phenomenon is well explained by sociolinguistics [17]. They can be found in our corpus for Romtels, for example, when a secondary school principal asks why ‘these’ Roma pupils should be enrolled in school, when the enrolment of pupils is compulsory and enshrined in French law, regardless of the status of their parents on French soil (even if they are in an illegal situation). This principal said he feared ‘communitarianism’, explaining that Roma children, especially from the same family, gather in the backyard to talk. When asked how many people this ‘communitarianism’ concerns, it was only five pupils out of the 600 pupils of the school.

3. Theoretical Anchors for Teaching Languages in an Intercultural Perspective

For almost 50 years now, many researchers, with Cummins [16] at the forefront, have advocated the use of students’ own languages in the classroom in order to promote transfer to new languages to be learned. Other more recent trends from the USA advocate ‘translanguaging’ [17], i.e., the use of any form of communication in the classroom, even hybridized (mixture of languages) in order to achieve the objectives of the course. In Europe, the notion of “plurilingual and pluricultural competence” [18], subsequently taken up by the CEFR and the companion volume [20,21], also values the use of all languages in the classroom for learning and mediation purposes [21]. We share Liddicoat’s views ([22], p. 12) about intercultural language teaching and learning, and argue that “The intercultural perspective has articulated a view of language learning that goes beyond questions of how language is acquired to consider how language learning is placed in an overall understanding of language learning as education for, and engagement within, linguistic and cultural diversity”. It is therefore important “to be aware of the diverse different forms of learning that are involved and which set up the complex process of language learning and use and the learning needs of language learners”.

The purpose to develop a model for language teaching in an intercultural setting is therefore based on the results of the academic research we have quoted in addition to our own work on these issues.

Teachers’ recurring requests and remarks during these research projects sustain the creation of a theoretical model to answer them: they do not know which languages are spoken by the pupils, nor how to use them as a resource for learning. They have questions about the material to be used, for the class dynamics which could be implemented implement with multilingual pupils, while including the parents, and the other teachers of the educational team. Another recurring remark relates to a feeling of incapacity, as a teacher, to offer enough opportunities in the classroom and more generally at school to develop language skills.

3.1. Taking into Account Teachers’ Redundant Questions

The aim, therefore, consisted of a search for possible solutions to these questions through a review of the existing literature.

Thus, work on representations or even stereotypes is a primordial and powerful lever. Intercultural education as well as the co-construction, with teachers, of multidisciplinary reflections [23] and actions involving fields that have nourished the intercultural approach such as language sciences [24], education [25], sociology [26], and social psychology [27], can allow for renewed perceptions and uses of the resources carried by the other at school, and in particular of the languages and social experiences of his or her repertory, for the greatest benefit of all.

A first idea for the development of the model is therefore to propose the implementation of pedagogical practices based on the link between the language and cultural experiences of students, lived outside school and in school since this is how the student’s repertoire develops. According to our observations [12] as well as those of many researchers [28,29,30,31,32] on the issues described in France [33,34,35], the phenomena of compartmentalization between school and home and between the classes themselves are still very prevalent. For example, classes that take in newly arrived pupils on a half-time basis (according to French law) for tutoring in French have difficulty communicating in terms of progression and programming with the regular classes (in mathematics, art, sport, modern languages, music) which the pupils also attend. In the end, French as a second language teachers are rather marginalized by the teaching teams. Secondly, there is compartmentalization in the classes themselves between family and school, where the home languages are still hardly used, even in French or modern language classes where language is at the heart of the issues; they are even less used in other subjects, even though inclusion in mathematics classes is compulsory from the moment these pupils arrive in France. How can they understand the lesson if they are not allowed to use their languages and educational cultures under the pretext of exacerbating their otherness?

In order to reduce this divide and “make a connection” in the sense of Edgar Morin [36] both between the spaces of the different courses and within the courses themselves, and between school and non-school time (which constitutes the dual movement of “the intercultural”, both rooted in time and in constantly evolving spaces), it is a matter of considering the pupils and their linguistic and cultural experiences as a springboard for the learning of the schooling language and the subjects. The focus is on finding ways to help learners get recognition and use their otherness, in the form of their language(s) and family or other school experiences, to support and enhance their commitment to formal learning, at all levels of schooling, from pre-school to upper secondary.

3.2. The Notion of Learning Territory to Develop an Intercultural Model for Language Teaching

The notion of the learning territory is currently experiencing a strong occurrence in the educational field. If, as Bier [37] points out, the contours of the notion are constantly being redefined, it is undoubtedly because it constitutes a major paradigm shift by placing the learning-subject at the center of his or her training and by acknowledging the territory as a partner in reciprocal collaboration. Since the beginning of the 2000s, Jambes [38] has explored the notion by reminding us that the “local” or the territory remains an inescapable fact of the human experience. In a globalized society, far from constituting a withdrawal into oneself, developing potentialities on the scale of the territory makes it possible to imagine and deploy new modes of action which are more consistent with local characteristics. The closeness between the individual and the place, the social and symbolic link that each person has with his or her environment, reminds us of the stakes of local development of different resources, in order to meet the contemporary challenges of our globalized society. Since the end of the 20th century, with such a mindset, many cities have embarked on local education policies that gather the various players in a complementary manner between the different structures (cultural centers, media libraries, conservatories, sports clubs, and the ministry of education). This establishment of local networks confirms the idea that education is not the monopoly of professionals alone, but a shared mission within a complex local fabric, made up of different informal or non-formal structures. These dynamics of exchange and partnership are becoming a strong axis of European educational policies that commit the states to defending the ambition of Long-Life Learning (LLL).

The actions of each of these educational poles are considered to be complementary to knowledge and skills. Although this paradigm of thought may be controversial (Bier [37], p. 16), it reminds us that recognizing a plurality of knowledge and skills does not mean falling into confusion between information, knowledge, and know-how, nor between knowledge and skills, but calls for them to be considered in their complementarity. Taking them into account and comparing them constitutes personal and collective enrichment, an opening, the chance to open up knowledge, cross-fertilization, and multidisciplinarity, and they thus become elements of social cohesion.

The development of a learning territory that is open to young people and their parents, first of all at the level of neighborhoods and then of a city, seems, in our view, to create opportunities to establish bridges between the different structures in order to create a functional network for families and the different partners or institutions.

Thus, following the example of Morin [39], we consider acknowledging this territory as a “complex” fabric marked by the interdependence of reciprocal knowledge and know-how. Morin reminds us that “the fabric of the complexus (what is woven together) is composed of heterogeneous constituents, inseparably associated (…) which raise the issue of the one and the many” (Morin [39], p. 21). The work of assembling the local “complexus” constitutes our main goal, it aims at making the territory in which young people and their families evolve, understandable and functional.

The model should be anchored in a broad context since a strong principle is to link formal, informal, and non-formal education.

Indeed, if we focus on the different non-formal educational centers attended by young people and their families, we notice the educational dimensions of these centers and the complementary interrelationships they have with each other and/or with the school institution. If we take the example of the development of language and social skills, we can only note the non-exclusive character of the school institution as the place of this teaching-learning.

In this context, these other teaching-learning poles become necessary axes of commitment for educational policies. We have thus identified the need for links between these different educational spaces/times (schools, families, associations, NGOs, sports and artistic activities, libraries, museums, etc.). Our approach aims to strengthen the cohesion between what is learned in different places (schools; homework help by NGOs, sports at school, and in associations or family activities).

A learning territory defends the ambition to federate rather than fragment these times and spaces of daily life. It is an approach of triple dynamics between the formal, the informal, and the non-formal that the model seeks.

3.3. A Model Based on the Recycling of Languages, Norms, and Social Practices

Linking the language skills developed in formal, informal, and non-formal settings prevents evacuating the languages learned and practiced outside formal contexts, and using them as a resource. Thus, the sought model is based on an intercultural approach that is part of an ecological framework: the recycling of languages and cultural experiences (Figure 1),developed in informal and non-formal environments.

Figure 1.

Model for recycling languages, norms and social practices.

Finally, the model should be an intercultural process that is part of an ecological framework, that of recycling languages and cultural experiences [40]. Recycling is a process of treating elements so that some of their materials can be reintroduced in the production of new products. We feel this process should be part of the proposed model. Interactions, potential conflicts, and linguistic or social interferences constitute these valuable moments of the (real) encounter which will allow the taking into account, then the awareness of the elements at stake (the reflection). Then, self-awareness allows the reintroduction of these materials concerning the specificities and universals relating to languages and cultures for learning and will, in turn, generate new inferences constituting the development of “meta” competences, which we could materialize by the following diagram:

The literature on metalinguistic learning in this regard is extensive. Candelier ([41], p. 9) explains that “in terms of metalinguistic learning, there is no need for sophisticated psychological models to show the need for articulation between language teaching practices. It is enough to remember the role played by the “known” in the apprehension of the “new” as postulated by general theories of learning and as illustrated by our daily experience. Further on, he adds: “But metalinguistic work in class is not limited to labeling. It generates and involves a whole range of knowledge, know-how and even know-how to behave” ([41], p. 12). This statement is corroborated by our corpus, which brings into play knowledge (what I know about languages and cultural experiences), know-how (especially on the part of the trained teacher, who stimulates a dynamic of reflection among the pupils), and interpersonal skills (knowing how to take into account the other in his or her singularity, while at the same time being myself). This proposal makes it possible to question the impact in terms of consequences on group dynamics. Our corpus indicates that consciousness and self-awareness are context-dependent. The context involves different speakers and it is through the interactions produced by the speakers that these phenomena appear. It can therefore be said that consciousness and self-consciousness are not only individual phenomena but also the product of a collective. These repertoires create the telescoping, the possible interferences. If we now consider that the momentum is collective and that the class is ultimately a vast collective language repertoire at the service of reflection, various forms of awareness, and then self-awareness, the languages and social experiences of the learners are no longer considered a difficulty (an ideology found in popular doxa), but rather a primary resource. Finally, are we not moving towards forms of collective awareness? These collective awarenesses can also be transformed into collective self-awareness, both on the part of students and teachers. Thus, irenic or agonal interactions, conflicts, and interferences are an opportunity to activate awareness and then self-awareness. However, it is necessary to set aside time for reflection, for pooling of remarks, in order to co-construct a collective awareness together. In this way, self-awareness will of course be individual, but it will also be a kind of collective memory, resulting from the sharing of experiences in the classroom.

3.4. Apprehending Languages and Culture “As a Whole”

An intercultural model for language learning cannot, in our view, only take into account several languages (plurilingualism) or the passage from one language to another (translanguaging), but consider language and cultural experiences as a fruitful whole where each experience can be at the same time the source, target or means of reflection on languages and cultures.

The model must be able to account for the diversity and complexity of each person’s identity and make it possible to envisage a dynamic and (self) reflexive relationship with oneself and with others, avoiding the processes of illusions and facades [42].

The model sought is therefore rooted in a pan-language approach, in order to consider language as a whole and made up of its languages, and cultural experiences.

This pan-language/cultural approach aims to take into account real-life experiences and bring interculturality to life in action.

4. Methodological Reflections on the Choice of the Figure of the Language Diamond

These theoretical reflections led to the development of a model of reflection comprising seven major aspects published in the 2021 Routledge Plurilingual Handbook in Language Education and on the European Commission website (https://www.schooleducationgateway.eu/tr/pub/latest/news/translanguaging-improvedresult.htm, URL, accessed on 27 April 2023): identifying the languages involved, using them as resources, through multilingual material, in classes and outside classes (museums, libraries, associations), with parents and all educational staff, making sure all students can support and be supported according to the various language and cultural experiences to be developed.

The figure of the diamond was chosen because a diamond cut with seven faces which matches the seven points of attention and recurring issues. Moreover, the diamond was chosen because it evokes a precious resource that aims to counterbalance the negative representation of the students’ alterity and skills. When the diamond is cut, it reveals an unparalleled brilliance, which refers to the skills and potential for success of young migrants. It seeks to deconstruct the stereotypes that we have mentioned in our studies. Indeed, interculturality is above all a work of deconstruction of stereotypes, here concerning the other (the migrant, speaking other languages and having different experiences). Proposing a model that can make people think in a renewed way (a diamond) initially helps educational staff to question themselves (Why such a metaphor? What makes it a new way to teach?), which encourages them to decenter themselves.

The cut diamond has seven facets. These faces, which develop an intercultural approach, must be considered as a whole and are not designed to be understood linearly (face four before face six for example). We have, thus, chosen a holographic model [39] where in each facet, the others are present. For Morin [39], a hologram is an image where each point contains almost the whole information about the represented object. The hologrammed principle means that not only is the part in the whole, but the whole is, to a certain extent, embedded in the part. Thus the cell contains the whole genetic information, which in principle allows cloning. Society as a whole, via its culture, is in the mind of every individual. Thus, intercultural perspectives that allow for the other to be taken into account in the construction of the self are always present, regardless of the face (e.g., including pupils, parents, alternative material, other teachers, or educational staff). The whole (the intercultural perspective) is thus embedded in the part (the facet) and the part (a facet) in the whole. The image of a diamond can also be used as a model to highlight the bonds between the atoms of the gem that give it its multiple qualities. In the proposed conceptualization, it is also the link, the synergy between the different reflections and activities proposed for each face that gives coherence to the model. In this way, the plurilingualism and cultural experiences of the student strengthen the diversity and complexity of the identity of each individual and the class, instead of ignoring or stigmatizing such diversity. Diversity is the springboard for interactions and activities with students.

Of course, in the collective imaginary, owning a diamond means being rich! This is an overtly militant way of counterbalancing representations of denial, or even of failures in the language and cultural skills of students, which suggest that they speak a poor language and that they have indigent social and cultural capital [43]. Furthermore, surveys show that education actors automatically associate economic capital with social capital and language skills, but this is not automatic. Even a leading sociologist in France such as Lahire [44] does not seem to be aware of the link between languages and academic achievement.

Despite this state of play, we are aware that it may be awkward to induce a positive mirror representation (brightness/brilliance/wealth) to counterbalance negative stereotypes (poor speaker, poor language). Indeed, imposing and superimposing a counter-stereotype [45] without deconstructing it, is counter-productive [4]. Being aware of this phenomenon, we always present this model with scientific data, recommendations on education (see websites in the bibliography), and pedagogical practices in the form of a booklet (https://research.ncl.ac.uk/romtels/resources/guidancehandbooks/ URL, accessed on 27 April 2023) or films (https://listiac.univ-montp3.fr/clip, URL, accessed on 27 April 2023) which, at the very least, make it possible to reflect and deconstruct negative representations in order to propose a renewed reflection on the plurilingual student. By offering scientific resources (the most decentralized level), resources for decision-makers (macro level), for teachers in schools and classes (meso and micro levels, in the guides, sites, and films), and surveys or testimonies on the impact of these measures on pupils (nano level, in the films for example), the aim is to implement the de-construction of stereotypes at all possible levels, and by as many actors participating in the education system as possible. We therefore assume, with full knowledge of the facts, to enter the Janusian binarity denounced by Dervin [46] in order to present an enhanced image of the other pupil in order- in a rather ideological way we must admit- to propose another representation while accompanying in different ways the deconstruction of clichés and aiming at a conception of plurilingualism and interculturality which reinforces societal cohesion.

After these introductory considerations about the considerations to elaborate the model, we propose to describe the different facets of the diamond as a result and to explain how each of them relates to general or more specific intercultural perspectives.

5. Discussion on the Different Facets of the Language Diamond

The diamond focuses on: 1. identifying the languages spoken by pupils and the cultural experiences they have had; 2. using all the languages and cultural experiences present in the classroom as a resource for teaching and learning; 3. using and creating multilingual and multicultural materials; 4. establishing mutual, reciprocal mentoring within the classroom; 5. Exploring multilingual and multicultural environments outside the classroom; 6. Using the linguistic and cultural resources of parents; 7. sensitizing the educational staff and teachers of all subjects about the plurilingual and intercultural approaches [47].

Note that in the model below (Figure 2), facet seven has been placed as the base, the foundation of the stone, to indicate that it is essential to discuss with colleagues and all co-educators in one’s school if the intercultural perspective is not to be implemented solely in the privacy of one’s classroom. On this condition alone, it can constitute an approach shared by the educational staff, whatever the roles of each staff member (teachers, supervisors, head teachers, etc.) in the school, and offer a coherent vision and practice of activities for the pupils (for example, some teachers should avoid denying diversity while others value it, or even over-value it, in order to mimic an ideology of “ the well-being of living together” that is inadequate as mentioned above).

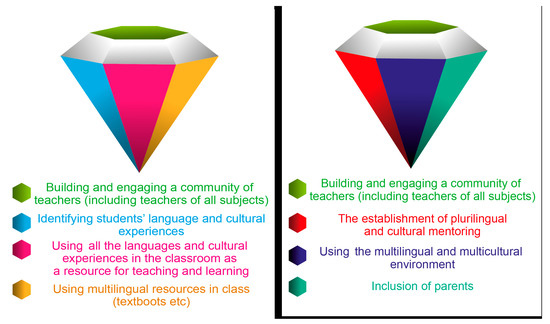

Figure 2.

The Language Diamond. Green: Building and engaging a community of teachers (including teachers of all subjects). Blue: Identifying students’ and cultural experiences. Pink: Using all the languages and cultural experiences in the classroom as a resource for teaching and learning. Yellow: Using multilingual resources in class (textbooks, etc.). Orange: The establishment of plurilingual and cultural mentoring. Violet: Using the multilingual and multicultural environment. Dark green: inclusion of parents.

5.1. Face 1, Identifying Students’ Language and Cultural Experiences: Towards a Recognition of Diversity and the Changing Complexity of Each Individual

Identifying the language and cultural experiences of the class and the school is a way of highlighting the repertoires that are often ignored by teachers who are caught up in a strong injunction to ensure academic success in French, which would imply forgetting all other languages and previous cultural experiences. Teachers, on the other hand, explain that they sometimes have the feeling, when pupils use other languages, that they do so to hide information from the teacher (they talk about something else than the lesson), or are even insulting adults and their fellow pupils [48]. If, on the other hand, we propose to identify and highlight the students’ languages and cultural experiences, we call upon a well-known principle in interculturality, which is the recognition of the other, in his or her complexity, to avoid ignorance or rejection, as is the case here. Recognition (re-con-naissance in French) is etymologically the fact of being born (birth/naissance) in interaction (-con prefix, with the other) in a constantly renewed principle (-re prefix) since, as Dervin [49] points out, interactions allow, in a continuous and perpetual movement, to apprehend, in a mutual attempt, both the other/the others and oneself.

Moreover, identifying diverse languages and cultural experiences present in the classroom, and more broadly in the school, does not stop at the students’ repertoires. It is also important for teachers, and all school staff, to identify these resources, not only for ontological issues of recognition but also to know who can offer mediation, and translation according to the needs of students, teachers, or parents. Duchêne [50] explains that Geneva airport, for financial reasons, when hiring new staff always chooses those who speak so-called ‘rare’ languages to be able to mediate in case of a problem with a traveler. This interest, which is well understood by international companies, is rarely replicated by schools, which live in a multilingual context. It is therefore understandable that acknowledging the linguistic and cultural experiences of all the students makes relations easier (Bauman by Dervin [49]), as each person can be, in turn, a subject, an object, or a mediator himself, depending on the needs, desires, and proposed work activities. For example, if a pupil does not understand an activity, another pupil or an adult can translate, know what is disturbing for the pupil and offer an explanation. The pupil who needed mediation may, at other times, become a translator, mediator, or facilitator. This fluidity of roles from receiver to provider allows for mutual recognition. The value recognized for each person helps to strengthen the learning community and value the linguistic and cultural experiences of all, rather than being ignored, which would be a source of fear and devaluation.

As for speakers, as Escudé and Janin [51] explain, any language can be a source, a bridge, and a target language, alternatively, depending on the needs. For example, students who speak Mandarin but also English can, when learning French as a language of schooling, use English as a bridge language to make inferences with French. This possibility will facilitate learning. English will become the target language in English language classes etc. Language and cultural experiences are therefore constantly multiform, in their roles, according to spatial and temporal situations.

This knowledge of more or less diversity at work in classes or schools also makes it possible to anticipate the domination of certain languages within the class (e.g., French against any other language in France or variations within the languages themselves, e.g., teachers who do not want to acknowledge the Catalan variant of gypsy children in the south of France). Acknowledging linguistic and cultural diversities helps to resolve tensions that may occur in certain situations and lead to hierarchies of languages and norms.

In practice, how can this theoretical principle of recognition be implemented? In order for activities to allow identification of the languages and cultural experiences of the class, avoiding stereotypes, and therefore in a dynamic and not a static way, which is the main issue of interculturality [52], activities can be carried out, such as language biographies (Figure 3, see also the Maledive website (Aalto, Auger, et al.: https://maledive.ecml.at/Studymaterials/Individual/Visualisinglanguagerepertoires/tabid/3611/language/fr-FR/Default.aspx) Majority Language and Diversity, URL, accessed on 27 April 2023). These practices, according to Busch’s [53] assumptions, are intended for students of all ages and levels of language proficiency. Their aim is to recognize the students’ linguistic and cultural repertoire so that, strengthened by their experiences, they (and the teacher, in a principle of reciprocity which is specific to intercultural approaches) develop greater linguistic and cultural security in the situation of learning a new language.

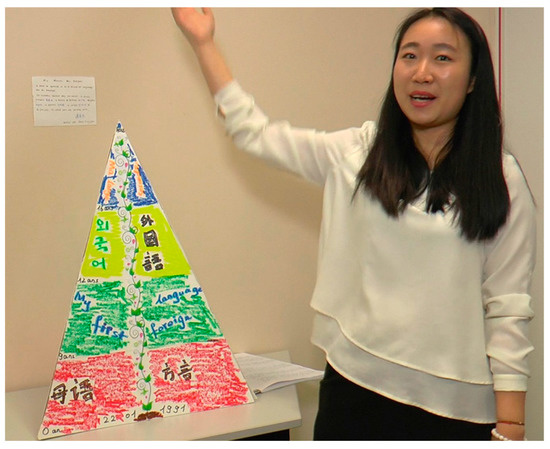

Figure 3.

Example of a language biography (languages, mobilities, and cultural experiences).

Other resources such as “Languages et grammars in ‘Ile-de-France’” (https://lgidf.cnrs.fr, URL, accessed on 27 April 2023) provide information on the linguistic characteristics of the pupils’ different languages. The aim of such a resource is also to be able to communicate with pupils, even in the absence of language mediators (oral and written interactions of everyday life are offered in various languages), or to anticipate possible transfers and difficulties in the language of schooling, depending on the specificities of the languages known by the pupils. The aim is in no case to know their languages in order to ‘correct’ them or teach them. The interest is above all psycho-affective and cognitive: it is important to recognize these experiences in order to reinforce benevolence, particularly linguistic benevolence [47] when teaching a new language, or simply through a language (such as in art classes). Even then, J. Aden and S. Echenauer [54] refer to the fact of being able to translanguage from one modality of action (painting, dancing, speaking), to others, in various languages.

This facet also enhances the identity of students in the classroom, which in turn can lead to increased student [55] and teacher [56] commitment as various studies have shown.

Making language and cultural experiences visible, in order to overcome indifference to differences [57], which is very prevalent in some classes, is a guiding principle of intercultural approaches. Biographical work is a key to defining oneself (see in this respect the use of biography to understand researchers working on multilingualism and education [58]), not in a permanent way, but in a renewed way, because nothing prevents us from proposing these activities throughout the year and noting the movements in the language and cultural experiences of each person. What we know is less scary. Thus “uncertainty, risk, insecurity, precaution, and fear have become redundant themes in the thinking of thinkers of the contemporary social world [59,60,61,62,63,64,65]. Drawing on the work of Riezler [66], who identified the relationship between ‘fear’ and ‘knowledge’ at both individual and collective levels as a fundamental question for social sciences, Jodelet [65] explains how cognitive processes and social representations are intimately involved in fear phenomena, as our previous analyses have also shown.

At this point, it is important to consider that acknowledging the paths of each person is quite different from the term ‘knowing’ which would ‘monolithize’ the representation of the other, offering a perception of finitude in non-coincidence with the complexity and the constant movement of identities. This is what Dervin [5] explains when he describes the cultural as liquid (following Bauman) in opposition to a solid vision. The latter, which is still widely shared in the media, for example, presents cultures as one and indivisible, the subject being pre-determined by the group (national, social) and its actions being predictable. This conception is developed by certain trends in social sciences which hierarchize values (the beautiful, the good), advocating an exhaustive knowledge of the culture and the language of the other by essentializing it through the individual. Fred Dervin’s [5] liquid definition places complexity, subjectivity, and interaction at the heart of the issues at stake and this is the perspective we share in the proposal of the first facet of this attempt at intercultural modeling of the language diamond.

Indeed, it is important to leave the possibility for everyone to (re)define themselves wherever and whenever they wish since time cannot be stopped and movement is perpetual. If students say they speak Gypsy, even if linguistically the language in question is a form of Catalan, they have every right to name the language they speak as their community acknowledges it, in a specific time-space in the south of France. In the same movement, it is also possible to become aware of the variation in Catalan. This awareness allows inferences to be made about French or other Romance languages taught in school in a secured way, playing on the proximity of language and cultural experiences rather than challenging them.

Thus, this first facet shares different intercultural as well as plurilingual dimensions. It aims, in fine, to support the development of skills expected by schools and curricula such as the language of schooling and subject contents.

5.2. Face 2: Using All the Language and Cultural Experiences in the Classroom as a Resource for Teaching and Learning

5.2.1. From Recognition to Action

The recognition of the other, and ultimately of oneself through the other, is a crucial guiding principle of intercultural approaches. This awareness is constantly updated in action and interaction [67]. This is why this new facet of the diamond proposes to use the language and cultural experiences of the classroom as a resource for teaching and learning. If we may regret the consumerist use of languages and cultures that a verb such as “to use” may induce, in the sense that we attribute to it, it is rather a question of being able to “employ” (in the etymological sense of this term which means “to mix with”) these language and cultural experiences, not only to recognize oneself but also so that the specificities of each one’s pathway may become a base, then a springboard for the appropriation of new knowledge. “Using” is therefore a process of mixing these experiences with the funds of knowledge [68] already present and now recognized for the development of new skills in languages for example.

Moreover, the notion of resources is also decried in the sphere of language education or intercultural studies for its consumerist use, as if languages and cultural experiences were marketable goods, both in the world of work and in institutions that teach languages. Sociologists, for example, Bourdieu [43], also evoke the problem of languages and cultures as a social and cultural capital which also becomes a criterion of hierarchy between speakers. Our position is that the terms (“use” and “resources”) have acquired, through dialogism, evolutions of meaning according to the contexts, and it is essential to be aware of this. However, it seems fundamental to us that research should also be able to reclaim the terms that seem important for its reflection, and the notion of resources is one of them (as it is for other researchers such as Cenoz [69]). An etymological reflection on this term led us to choose it for this second facet. Indeed, this word comes from the Latin “to resurrect, to regenerate” and this idea of having recourse to experiences finally recognized in their own right “to overcome difficulties”, according to the dictionary definition, covers exactly the objectives of the proposed diamond model. Finally, already in the 18th century, D’Alembert [70] also evokes the resources of a language, the means it offers the writer to render his thought. Even if the most shared meaning in today’s consumer society is that of marketable goods, it is important to reclaim the meaning of “resources” (We can note the same movement of reclaiming the term in the discourses for the taking into account the environment, for example, F. Blot, 2005, “Discourses and practices around “sustainable development” and “water resources”, a relational approach applied to the Adour-Garonne and Ségura basins”, doctoral thesis, Toulouse 2) to show how much language and cultural resources can serve as prerequisites for learning, shaping and sharing one’s thought, in D’Alembert’s sense.

Using one’s own language and cultural resources also allows learners and teachers to co-construct, each on the basis of their own experience, rather than react to experiences perceived as embarrassing because they are too singular for teachers (rare languages, stereotyped cultures because they are unknown, etc.). Action, after recognition, to counteract potential clichés is an important principle to be a force of proposal in a classroom or an institution where activity is the basis of all learning. Successful completion of academic tasks in the language of schooling, in other modern languages taught in school, and in different subjects, is crucial for pupils. It is the key to their success.

Two main families of activities to act on and/or reflect on are proposed.

To this end, we propose activities through two broad families to use languages as a resource: they can be used to help understand, speak, read, and write. We can also talk about and reflect on languages and cultural experiences. These two families of activities are complementary. They mobilize existing language and cultural resources to facilitate the appropriation of new language and cultural experiences and new subject content.

5.2.2. Acting On

Thus, in the first of these cases, the language and cultural resources of the pupil will serve as a support for learning, particularly in the case of misunderstanding during reading or when receiving an instruction for example. Indeed, rather than thinking in terms of a language barrier, let us consider the resources finally recognized by the pupils as an aid to learning. A learner reads a text that he or she does not understand: he or she can look it up in the mono/bilingual dictionary to make it his or her own, browse automatic translation software, ask a fellow student who shares languages or social experiences or any member of the educational community who may have been identified as a resource for translating or interpreting the text.

These activities may seem self-evident, but it should be noted that this year for the first time in France an allophone pupil (i.e., one who arrived in France less than 18 months ago) was entitled to the use of a bilingual dictionary during assessments (NOR: MENE2203999N, memorandum of 3-2-2022, MENJS—DGESCO A1-1—MPE “As of the 2022 examination session, allophone pupils newly arrived in France (EANA) are authorized to use a bilingual dictionary in the French, history-geography and moral and civic education examinations of middle school and high school certifications”). Furthermore, the Ministry of Education prohibits the use of telephones in classrooms unless “a pupil with a disability or disabling health condition can use connected equipment if his or her health condition so requires” (https://www.service-public.fr/particuliers/vosdroits/F21316, URL, accessed on 27 April 2023). Multilingualism is therefore not included in this framework and is subject to exemptions that are sometimes requested in certain schools which understand the value of using language and cultural experiences that already exist.

Allowing oneself to use all the language and cultural resources at one’s disposal to understand, speak, read, or write is essential. These practices are more effective in fostering the development of skills in a new language and discipline. The very fact of being able to decenter oneself thanks to pathways through another language or experience, is specific to interculturality and further strengthens the appropriation of new knowledge and the development of skills in a place of acknowledged otherness.

This is why a second family of activities is proposed. Through the use of these language and cultural experiences, the aim is to reflect on known practices in the light of the new language and cultural practices at work. Thus, writing, speaking, and reading in different languages in order to better understand the language of schooling and the disciplines also makes it possible to compare languages and, more broadly, lived social experiences. Comparing is an ordinary cognitive activity that fosters both the transfer from one language to another, from one norm to another, from one social practice to another, but also the decentration which shifts the experience set up as a norm into a singular construction even if it may be widely shared by a group.

5.2.3. Reflect On

Contact between languages and cultures is often seen as negative because it can lead to mistakes: “It’s poorly said. It’s a mixture of bad French”. Certain specificities of the languages and experiences of learners can indeed lead to misunderstandings, even disputes, and forms of devaluation (not being able to hear a phoneme that is not in one’s known languages, acting according to known social practices which are not in use in the new space where one is evolving). However, these points of contact that may become conflicts are a wonderful opportunity to reflect on languages and language or social norms [24]. An error is a stage in learning and allows a better understanding of the language and cultural experiences to be assimilated as well as the more general functioning of language and languages.

Explicitly putting into perspective (since cognitively this perspective keeps happening), in the classroom, the different linguistic and more broadly social experiences are not intended to classify idioms or norms but rather to become aware of the singular universals that characterize the functioning of our societies [71]. Thus, with regard to language and social practices, all languages have a syntax, such as the way negation is marked, but each does so differently. All societies offer forms of politeness [72] but each will update it in specific ways (body, gestures, voice intonation, verbal forms, etc.).

Languages and cultures are cognitively co-constructed for both the pupils and the teacher. In this way, each one can understand why some errors emerge (processes of analogy with known systems, for example), and an awareness of the specificities of languages and norms is then created, thanks to decentration, in order to put one’s productions and representations into perspective. In this intercultural approach, each person is an expert in his or her own path (the teacher as well as the pupil), and each one discovers the other’s reference systems (the teacher, without knowing the details of the pupils’ experiences, understands the way they behave) in a relationship of empathy, with the other. It is not always a matter of agreeing, on a soothing conception of interculturality where the (good) togetherness would only need to be evoked to be experienced. Interactional and cognitive conflicts are very interesting and motivating and allow for shifts in postures and forms of self-regulation in relation to one’s own experiences. It is also essential to understand that others, such as me, may have their own difficulties. This understanding allows one to put one’s own conceptions into perspective. Putting things into perspective [73] is also a founding principle of interculturality. Experienced norms are contextualized, they are related to situations. Understanding this constitutive phenomenon of interculturality makes it easier to decentralize. This awareness provokes an indulgence towards oneself, the first step towards a greater movement of humanity towards the other. The consequence of this type of activity is valid for the pupil and for the teacher who is in constant interaction with the pupils, as an expert in French and its learning, but in an intercultural situation of discovery of languages and experiences already lived by the pupils, sometimes in a groping manner, but always with a genuine interest in the pupil’s identity, an attitude that motivates all pupils to assimilate French. Thus, having integrated the Other into oneself means never again looking at others as completely different. It means accepting what they have in common and what is different [74]. The general objective would then be openness to the Other, which is only one particular aspect of open education. It is with his/her own words that the bilingual person builds his/her second language, his/her other self.

5.2.4. Compare

Etymologically, comparing means “putting in pairs”. We are far from the usual representation of hierarchy and domination. The meaning of comparing implies this dual complex phenomenon which can involve the fact of “putting by pair”, dissociating, choosing, devaluing, etc.

The comparison activities (Figure 4) are part of an intercultural approach that claims complexity: accepting that otherness is both the same and the other while avoiding any form of cultural dogmatism that would lead to thinking that the other is a prototype of his or her group. Because in short, the relationship to the other is of primary importance, rather than the cultural relationship as such [75]. The aim is therefore not to focus solely on differences, but to identify points of convergence, since every subject carries his or her social, language, and communication experiences. These common points are rooted in what Galisson [71] calls singular universals, which imply that all human beings have particular relationships to the major fields of life, such as family, food, health, etc. The differences arise from the fact that everyone (at the societal but also subjective level) then understands these domains differently simply because the environment and the sociopolitical and historical contexts are singular. These phenomena exist from a cultural point of view but also from a language point of view. Thus, one can always find different but also common elements at acoustic and articulatory levels, at lexical and grammatical levels (relations between the actants) for example. These phenomena, both linguistic and social, evolve according to each person’s path.

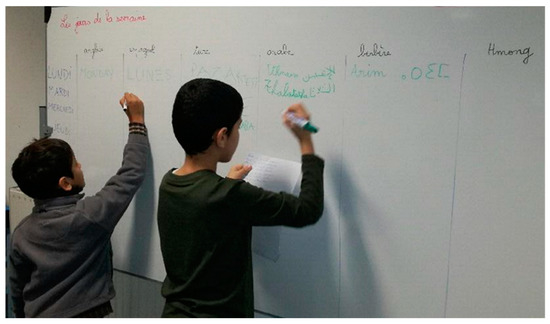

Figure 4.

Pupils write in the languages known by the class in French, the language of schooling, English, Spanish, languages taught at school, Turkish, Arabic, Berber, Hmong, and family languages, and reflect together on the singular universals of languages [40].

This intercultural approach is also a driving force for pupils. It arouses interest because it focuses attention on the pupils, their knowledge and experience of languages and cultures. It, therefore, encourages the desire to express themselves. The classroom situation can then become a framework for exchanges, a phenomenon that diversifies the types of interactions (not only teacher-pupils but also pupils among themselves). The communicative act becomes more natural because of the involvement of participants. Finally, the interest is that the pupils are involved in their learning, they construct it, assuming it as far as possible. The effects of these intercultural principles through the meta-reflection activities implemented have an impact on the motivation of the pupils according to the results of our studies [12].

Other activities such as those developed by Hawkins [76] (language awareness) or Candelier’s [77,78] reflections about an awakening of language (“Eveil aux langues” in French) are close to those we have just proposed. Including this perspective in an intercultural framework is interesting in order to take into account all the language and cultural experiences existing in a classroom.

In the language diamond, starting from oneself, one’s identity, knowledge and thoughts are the basis for learning.

Thus, activities comparing language and social experiences can be carried out in all subjects to develop an awareness of transfers between languages, to gain confidence in one’s language repertoire, and to use it as a springboard for learning. These activities make the use of languages in the classroom more commonplace, and reinforce equity and language security: the pupil has confidence in the fact that the languages and experiences in his or her repertoire will enable him or her to learn the language of schooling better, to better understand the school subjects and the other modern languages taught at school.

In subjects such as geography, repertoires can be used to talk, for example, about borrowings and exchange between languages concerning the world’s oceans (Combat+ project). For pupils who are already fluent in the language of schooling, these activities help them understand their own language better by comparing it with others, and thus to memorize the content of the subject better. In other subjects, languages can be used at any time to understand a history or physics document. The possibilities of working with them are endless.

By reintroducing the other as this Subject, in the interactions, everyone can (re)define himself/herself and learn.

5.3. Face 3: Using Multilingual Resources in the Classroom (Textbooks, Books, etc.)

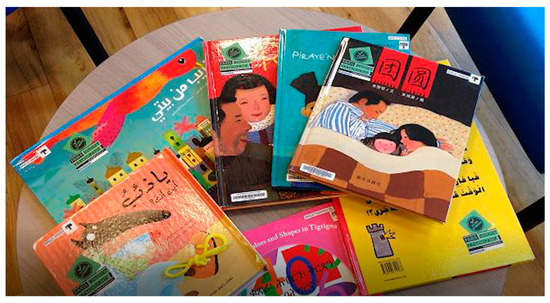

The introduction of linguistically and culturally diverse materials into the classroom is important for the multilingual and multicultural classrooms of the 21st century (Figure 5). The latest UNESCO Global Monitoring Report on Education 2018 (https://fr.unesco.org/gem-report/, URL, accessed on 27 April 2023) highlights the importance of using materials that represent the diversity of the population, the contribution of migrant populations in all countries, and training in the construction/deconstruction of stereotypes. The introduction of multilingual and multicultural materials helps to create links between the students in the class and the teacher. These materials reinforce the recognition of the singularity of each individual while reinforcing the shared, universal character of human experience [79] as experienced by all humans.

Figure 5.

Support “illustrating” cultural and linguistic diversity in a first-year primary school classroom.

The presence of diverse materials allows the co-construction of a shared culture, which is specific to each class, and to each spatial and temporal context.

Beyond the strict intercultural contribution, offering multilingual and multicultural material such as books, manuals, albums for children, videos, audio documents, and documents translated into the pupils’ home languages allows for a better understanding of the subject content. Pupils should not wait until they are fully competent in the language of schooling before continuing to progress in the various school subjects. It is not a question of permanently translating into languages already known, but of allowing, by all possible means (through images, diagrams, verbal and non-verbal actions), to facilitate access to meaning and its construction, while promoting living together in a context of diversity. For example, one should not hesitate to use online documents in family languages or documents translated by the pupils themselves in order to use them as resources for the class or the school. It is about encouraging pupils to bring the material they have in their possession to share with others, as in the example of Anne-Laure Biales’ [80] thesis in which pupils share their reading in various languages with the whole class in literary interpretative debates. Another example is the various story bag initiatives in Geneva (Switzerland) (https://edu.ge.ch/site/archiprod/les-sacs-dhistoires/, URL (accessed on 27 April 2023) or Toulouse (France) (https://pedagogie.ac-toulouse.fr/casnav/les-sacs-histoires-plurilingues-kits-telecharger, URL, accessed on 27 April 2023) where parents were able to help translate stories into various languages, both written and oral.

Pupils can also bring textbooks they used in their previous schools to encourage a connection with the educational cultures they experienced before arriving in France.

While this diversity in the materials is desirable because, in the surveys, the materials do not reflect much of the languages and experiences of the students, great care must be taken. Indeed, as Auger [6] or Dervin and Keihas [81] suggest in relation to textbook analyses, the authors demonstrate how textbooks most often construct a solid identity of the other, for example, the French person whose language is learned despite attempts to diversify this otherness by presenting other French people (French-speaking world, immigrants).

The material is therefore not free of solid explanations to account for reality. Dervin [49] proposes to move towards the analysis of the co-construction of what he calls the various diversities of the subjects involved rather than looking for marks of cultural diversity (at home, we do it this way, etc.). It is particularly important regarding materials used in class, whether they are manufactured or authentic. Discourse analysis, which does not seek the truth but is interested in the sometimes paradoxical, stereotypical, and more or less evolving representations, which constitute the discourses (oral or written), is a very useful tool. Discourses themselves are necessarily driven by various voices (the Bakhtinian dialogism [82]) which should also be taken into account. A novel or album written by an author from the student’s country of origin will probably contain stereotypes. Furthermore, the image of the other most often offers a hollow self-image, which can also be monolithic. It is therefore important to train pupils to identify these stereotypes, which may arise in the form of images and speeches. The same applies to youth books or novels in different languages or from different cultures. It is interesting to use them, as pupils can recognize elements and feel secure. At the same time, one should not be naïve, as these materials can also be used to discuss the representativeness of what is being told or shown (images) and to address the issue of clichés. Once again, the intercultural principles of objectification through perspective, decentration, and relativity must be implemented so that the introduction of this type of material may not be a hollow, or even stereotypical representation of the linguistic and cultural diversity supposedly present in the classroom. Having students, parents or teachers observe, discuss and analyze the generalizing forms of discourse in these materials (e.g., The French are/do…; In France, they…), proposing sociological (statistics), historical, anthropological, historical arguments to reflect on the documents brought by students, parents or teachers are more opportunities to deconstruct the reality proposed as genuine or undeniable. It is a question of questioning the “natural” character at first sight of the reading grids that could be generated by the use of these materials, supposed to inevitably coincide with total representations of otherness.

Again, in the interactions, pupils and teachers will have the opportunity to (re)define themselves by confronting these materials rather than integrating them as representatives of their cultures for example. The discussions will allow everyone to become aware of the variations that exist regarding the norms that may be conveyed by textbooks or youth books.

5.4. Face 4: Establishing Multilingual and Multicultural Mutual Mentoring

The choice of the term “institution” expresses a strong desire to institutionalize mentoring in the classroom as a facet of the diamond. Mentoring is an antonomasia of the Mentor who, in Greek mythology, is the tutor of Telemachus and the friend of Odysseus. The idea on this side of the diamond is, to follow certain intercultural principles, that language and social experiences can be shared by both, in the form of backing up. Furthermore, for this implementation to be relevant, mentoring should be part of a principle of reciprocity. In this way, each person can experience a complex and shifting identity where one can be both a knower and a learner, illustrating a founding theory of anthropology [83] on the gift and counter-gift. For Godbout [84], giving is not, first of all, giving something, it is giving myself in what I give. Giving/counter-giving makes it possible to create and maintain social links between individuals, not only in the sphere of close relations but in any social activity: to live in a society it is important to be able to ask, to give, to receive, and to know how to give back (in various forms) what one has received.

In language education, we are mostly familiar with the linguistic tandem (https://tandem-linguistique.org/?lang=en, URL accessed on 27 April 2023) which is a form of mutual mentoring that allows a student who wants to learn a language (for example, a child who has recently arrived in France) to exchange French lessons “for” lessons in his or her language. This activity creates symmetrical relationships, based on sharing and recognizing each other’s expertise. However, in the multilingual classrooms of our study fields, French-speaking pupils are not always willing to learn the languages of other children (e.g., oral, African languages). Reciprocal mentoring is therefore sometimes difficult to implement. Consequently, it is important to ensure that pupils always have experiences to share, even beyond languages (Figure 6). A pupil can thus exchange help in French for help in music, arts, sport, or other modern languages taught at school. In this way, the relationship can remain symmetrical to avoid any negative feeling of superiority/inferiority, which would hinder the virtuous circle of “giving-receiving-giving back”. If the pupil is always in a mentor position, he or she may develop an attitude of contempt, exclusion, or feel subservient to the other children with a relatively lower level of competence and whom he or she must teach.

Figure 6.

Establishing mutual mentoring: here Mourad helps Amid by translating into Arabic (Amid needs to develop his French skills). Amid, on the other hand, helps Mourad with mathematics because, as he comes from Syria, he has explored certain mathematical concepts in greater depth than those presented in the French curriculum. Furthermore, Amid and Mourad both love working on computers and prefer to use this tool to exchange their skills and knowledge.

On the other hand, the student who is regularly supervised may perceive himself as incompetent and no longer dare to take initiative. It is, therefore, necessary for the teacher to encourage, depending on the curriculum objectives, the creation of mentorships that mitigate this potential dynamic, ensuring that opportunities for reciprocity arise in order to initiate sustainable mutual mentorships where each contributes to the others while, at the same time, being nourished by them. Mutual mentoring aims to reduce the determinism, binarity, and stereotyping of the various identities at school: I am a migrant (that’s all I am), I do not understand French well yet (and I am incompetent), I come from another country (I am a foreigner). Mutual mentoring allows for a complexification of identities in favor of a multi-faceted approach to identity where it is possible to say and act as follows: I have just arrived in France, I am learning French, I am more advanced than my classmates in the maths and English curriculum, I enjoy drawing and football, I play video games, etc. So, having knowledge in various sectors will be useful at any time to exchange with others: to give, receive and give back.

5.5. Face 5: Using Multilingual and Multicultural Environments (Outside the Classroom, School) as a Resource

At this stage, it is important to question the notions of formal, informal, and non-formal education in order to establish lasting relationships between these different forms of education. The language diamond is not only experienced in the school domain but in all contexts experienced by learners.

It should be remembered that although the school is the sole holder of learning regulations, it shares its mission with other field players, particularly through associations: literacy, homework tutoring, academic support, and cultural and sports associations. Indeed, the range of activities that promote learning but are not part of the school is vast, covering numerous initiatives carried out by structures, often organized into movements, such as federations of new or people’s education, campaigning for the right to education for all, by all and throughout life. Many of the associations for people’s and new education were initiated by teachers and researchers wishing to respond in a different and complementary way to the needs of social transformation, for example through inter-generational education or experimental educational approaches. In a more indirect but no less essential way, cultural actions, which make territories more dynamic, such as the development of media libraries or activities carried out in the public space (cultural festivals, street libraries, etc.) help to invite families and individuals, whether they are migrants or not, to take part in community life. These other (non-formal) education centers complement each other in their missions of inclusion, welcoming, and the teaching/learning of languages and cultures, thus encouraging, through this continuum, the reassurance of learners through various language and social experiences. These different learning spheres are above all spheres of socialization. Thus, these places of linguistic and intercultural exchange allow the numerous ramifications of diversity to be taken into account by promoting the social co-construction of young people. At the community level, we have observed that the existence of these different resource centers is sometimes unknown or poorly known to young people and their families, as well as to the school actors who often work nearby.

Depending on the area, and more specifically in the local social fabric on which we based our research, we found that there is often a large supply of training in the non-formal school sphere. These different resources: family support associations (tutoring, literacy training for young people and their parents, parenthood support, sports clubs, etc.) operate too often side by side with other training areas, particularly in the education sector, without any real work on linking the knowledge built up for/by young people. These different teaching-learning spaces, far from collaborating with each other, often ignore each other and/or offer more cumulative than collaborative resources. Based on this observation, we seek to place the training of young people in a social learning space where the various actors, and stakeholders in education (teachers, researchers, pupils, parents, associations, or other partners, etc.) exchange their views through interaction dynamics for a better educational continuum. Each place of learning, whether institutional or not, can be seen as a resource center whose common objective is the social and educational inclusion of migrants (Figure 7). Thus, school is just the tip of the educational iceberg [85]. A school-centered vision of learning poses limits to inclusion, all the more so for young migrants. On the other hand, thinking about the interactions between these different poles, a continuum dynamics, makes it possible to go beyond exclusive categorizations that do not take into account the complexity of the educational fabric or the needs and resources of young people. Each of these places of formal and non-formal action, hybridize if they interact and place young people at the center of a co-construction space of their own training and of their language and social skills development. This is why this aspect of the diamond consists in exploring these eminently multilingual and often little-explored contexts. These non-formal or informal places of socialization in the public space can be as simple to approach and include in learning as signs in shops. Indeed, shopkeepers who are themselves multilingual, sell a variety of products, signaling (as on the photo below in French and Occitan, near Montpellier) such as street names (https://www.languagescompany.com/projects/lucide/, URL, accessed on 27 April 2023).

Figure 7.

Example of a street in French and Occitan in the Occitanie region, France.