Abstract

In this paper, we examine how universities can evaluate the level of support they provide to help their students with affective, behavioral, and cognitive engagement in their online and blended learning experiences. Additionally, it identifies what types of supports help students engage academically and what barriers hinder their online engagement. Using a survey instrument sent to university students (n = 1295), we conducted a mixed-methods analysis to understand better how students feel the institution supports their online engagement and what barriers they experience. To accomplish this, we addressed the following research questions: (1) How do students feel the institution supports their academic engagement for online and blended learning (including affective, behavioral, and cognitive dimensions)? and (2) What are the barriers to student academic engagement for online and blended learning at the institutional level? We used the Academic Communities of Engagement (ACE) framework as a lens for understanding the types of support institutions should provide in online and blended learning programs. While our descriptive statistics revealed that students might not distinguish the types of support they receive, the qualitative findings suggested they need more behavioral support. Our results also showed that 31% of students reported they experienced three or more barriers to their learning, which should be addressed when considering institutional support elements.

1. Introduction

Many researchers focus on student engagement, yet the field has not agreed on precisely what student engagement is. A standard definition that many agree on is that student engagement constitutes three dimensions: affective (emotional), behavioral (physical), and cognitive (mental) [1,2,3]. Student engagement has also correlated strongly with academic success [4,5], thus requiring that learning environments support student engagement [6,7]. Several studies suggest that interaction, community, and relationships in a learning environment may support and even increase student engagement [8,9,10]. Because of these findings, many educational programs have tried to implement support structures to aid student engagement [6,7,11,12].

There is usually a wide range of interventions and supports available to help students engage in the learning process and succeed in school in traditional in-person classrooms [13]. Instructors often employ several strategies to increase student interaction with each other, including smaller class sizes, peer tutors, and frequent small group activities [14]. There are also strategies like increasing time on task, fostering positive relationships between teachers and students, reinforcing positive behaviors, giving students more control and autonomy, and ensuring content is appropriate for their abilities [14,15]. The research has demonstrated that these strategies and methods are effective in a traditional classroom. However, research on providing student engagement support in online and blended learning settings is sparse, even though blended learning is increasingly being promoted for its engagement-enhancing capabilities [7,13,16,17].

The COVID-19 pandemic revealed the necessity of many institutions to adopt an institutional plan to improve their online and blended learning programs and support student engagement in these environments [16,18,19]. The Academic Communities of Engagement (ACE) model [18] provides a framework for supporting student engagement in online and blended learning environments. ACE suggests that providing students with support from their course and personal communities can increase their ability to engage in online and blended classrooms. Each community consists of actors (supportive persons) with varying levels of expertise, experience, and skills to support students’ engagement in different modalities. Through the ACE model, institutions can evaluate students’ cognitive, behavioral, and affective engagement to uncover what additional supports a student might need to succeed academically and how a student’s personal and course communities can provide that support [18]. If both communities provide active support, students are more likely to achieve academic success.

The purpose of this study is twofold: (1) to examine how a university can evaluate the level of support it is providing to help students with affective, behavioral, and cognitive engagement in online and blended courses and (2) to understand what types of things enable students to engage academically and what barriers there are that prevent students from engaging academically. This study also provides a case example of a university assessing institutional support for academic engagement to inform institutional decisions related to reducing barriers to engagement and increasing support for engagement in online and blended coursework.

Research Questions

This study will address the following research questions:

- How do students feel the institution supports their academic engagement for online and blended learning (including affective, behavioral, and cognitive dimensions)?

- What are the barriers to student academic engagement for online and blended learning at the institutional level?

2. Literature Review

In this literature review, we first provide context and a summary of student engagement in light of the Academic Communities of Engagement (ACE) framework [18] and justify its use as a model for this study. We also explore existing literature that addresses models for institutional adoption of support to aid students’ ability to engage in online and blended learning environments.

2.1. Academic Communities of Engagement (ACE) Framework

Student engagement is a vague term in educational literature with numerous interpretations and definitions [2,7,13]. Despite its nuanced definition, we understand that supporting student engagement is central in online and blended courses, as these environments more easily lend themselves to issues of isolation [20], barriers to technology [21], and the need for greater self-regulation [16,22]. A focus on academic engagement in online and blended learning settings is central to the ACE framework, which intends to clarify many issues associated with defining and measuring student engagement. It also clearly describes the three dimensions of engagement—affective, behavioral, and cognitive—and points out that each type of engagement may also exist independently despite often being associated. The following are definitions of each type of engagement as defined in the ACE (2020) model:

- Affective Engagement: “The emotional energy associated with involvement in course learning activities” [18] (p. 813).

- Behavioral Engagement: “The physical behaviors (energy) associated with the completing course learning activity requirements” [18] (p. 813).

- Cognitive Engagement: “The mental energy exerted towards productive involvement with course learning activities” [18] (p. 813).

A student’s ability to engage affectively, behaviorally, and cognitively is determined by facilitators (influences) of engagement [12,13]. A learner may possess several facilitators that can contribute to their success, including intrinsic motivation, an interest in the subject matter, or the ability to self-regulate [18]. Additionally, a student’s ability to engage may stem from their course environment where teachers use pedagogical strategies to directly or indirectly affect their ability to engage and their personal community, including family members, friends, and other associates [17,18,23,24]. The ACE framework identifies how students engage and where they receive or lack adequate support from facilitators to cultivate the engagement necessary to achieve academic success.

Communities of Support

The two types of communities identified in the ACE framework as sources of support for student engagement are (a) the personal community and (b) the course community. While the personal community consists of families, friends, and other associates outside of the school environment that exists beyond the timeframe of the course [18,23,25], course communities include actors embedded within a course, including teachers, peers, and administrators [17,18,26]. These course community actors are temporary, existing only during the allotted time of the course. Despite their different actors, timeframes, and characteristics, these communities play a unique role in supporting students [18].

Among the critical aspects of these distinctive communities are how communities can support students, or what are known as the support elements. A support element differs from a facilitator because it refers to the methods communities can employ to assist students instead of the specifics of a supportive environment [18]. While it is essential to understand the definition and purpose of facilitators, support elements lead to actionable strategies that support communities can implement to help students succeed academically.

2.2. Engagement Support Elements

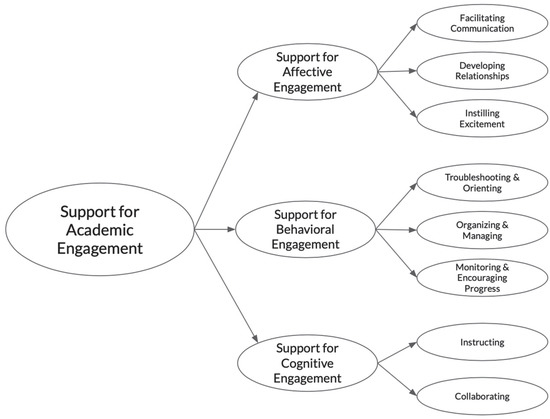

It is important to identify specific support elements appropriate for different types of student engagement so actors in students’ communities can assist their students. The ACE Framework [18] defines support elements that influence engagement differently and provides insight into how these support communities aid their students in engaging in online learning. See Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Support Elements in the ACE Framework.

2.2.1. Affective Support Elements

Affective support aligns with actors’ abilities to develop relationships and facilitate communication [13,17,18]. Additionally, it considers student self-efficacy, or how well a student expects to do in a course, and how they value the course content [27,28]. The necessary level of affective engagement may be challenging to reach if a student does not appreciate the course content or does not expect to succeed in the course [29]. Online communication requires a different skill set than in-person communication and can seem less personal [20,30]. Thus, students who lack the skills or confidence to communicate and build relationships online must have support. For example, some students may need someone else to initiate conversations or be encouraged [30]. The Community of Inquiry (CoI) framework [31] stresses the importance of having both social and teaching presences online; however, these alone do not foster the relationships necessary for adequate affective engagement [18,19,32]. After establishing a social presence, the group members must become invested and cultivate a community [31]. Organizing students into small groups is one of the most effective ways to create this type of community online [33].

2.2.2. Behavioral Support Elements

Behavioral support elements include troubleshooting, coordinating, and monitoring progress [13,18,21,34]. Borup et al. [18] note that these elements do not directly relate to mastering the content but are often necessary to assist students in fully engaging in the learning process. This support element becomes vital with the added complexity of online and blended courses. de la Varre et al. [21] note that one of the primary reasons students drop out of online classes is a lack of familiarity with the course platforms and technologies. Students may also need support to organize their physical learning spaces, learn self-regulation strategies, and minimize distractions. Students often have greater control of their learning in online and blended learning settings, but this can also mean they are more likely to procrastinate, negatively impacting their performance [22]. The flexibility of online and blended courses makes monitoring progress an integral element for keeping students on track [35].

2.2.3. Cognitive Support Elements

In the ACE framework, instruction and collaboration contribute to cognitive engagement. Instruction occurs when people share knowledge that allows students to acquire new skills and understanding [13,18]. Instruction can include presenting material, summarizing content, eliciting feedback, sharing resources, and clarifying misunderstandings [36]. Individuals with knowledge in specific content areas can offer subject-specific instruction, while those without knowledge can still provide general instruction, such as feedback [18].

Students collaborate when they work together “to co-construct knowledge that neither had previously or to develop a product they could not have created individually” [18] (p. 816). Even though many online courses have emphasized flexibility at the expense of teamwork, students’ collaboration is considered a crucial component of good online instruction [33]. While collaboration has been more prevalent in blended or traditional classrooms, many collaboration tools are becoming available and commonplace in online courses, such as social annotation and synchronous and asynchronous video.

2.2.4. Perceptions of Support Elements

According to Conceiço & Lehman, online learners perceive self-care, institutional support, friends, family, peers, and instructors as crucial supports to being engaged affectively, behaviorally, and cognitively [37]. Although students emphasized the need for instructors’ presence, they also felt that having a network of instructors, family, and friends was equally valuable [37]. In another study, students in an online doctoral program considered faculty, mentors, family members, and coworkers as sources of support, but these support groups also occasionally inhibited their engagement [38]. By examining student perceptions of the support that they receive through the ACE framework, we can identify the best methods and strategies institutions can adopt to facilitate these support elements to increase student engagement and achievement in online and blended courses.

2.3. Institutional Adoption for Supporting Student Engagement

After identifying these support elements, programs may need to adopt a specific plan at the institutional level to ensure the critical support elements for engagement are in place and accessible to all students [39,40]. Providing support for student engagement at the institutional level can prove critical for the success of online learning programs. Casanovas has argued that when individual instructors implement online or blended learning strategies separate from the institution, there is often a gap in the growth of a program, even if both the institution and the individual instructor favor an online or blended learning approach [41]. Additionally, Casanovas has pointed out that adoption models of online or blended learning programs usually focus on individual adoption without explaining how to accomplish institutional adoption [42]. However, having a well-defined vision and strategy at the institutional level is crucial to adopting a program initiative [39,43]. Embedding academic support within an institution’s online or blended learning program can help ensure no disparities between courses and that all students have equal access to the support they need to succeed academically.

3. Methods

In this section, we will discuss this research study’s participants and their setting’s context. We will discuss our research design, including data collection methods, analysis, limitations, and ethical considerations.

3.1. Participants and Setting

The participants for this study (n = 1295) were students at a university in South America in 2021. At the beginning of the Fall 2021 semester, enrolled students at the university were asked to take an optional survey to reflect on their experience in their online and blended courses from the previous semester. The 1295 students that responded to the survey came from various degree programs and specialties and represented 14.2% of the university population.

This South American university is a private, not-for-profit higher education institution with High-Quality Accreditation Status awarded by the Ministry of Education of [location masked for blind review]. It serves the people of [location masked for blind review] and has an academic offer of 109 programs at the undergraduate and graduate levels organized into six colleges: Economics, Administrative and Accounting Sciences; Social Sciences; Humanities and Arts; Legal and Political Sciences; Health Sciences; Engineering; and Technical and Technological Studies. Following the principles of autonomy, harmony, knowledge, and citizenship, this university aims to innovate in educational processes, influenced by creativity, digital transformation, and research, aligned with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). Although it delivers most academic programs in person, the university has an enduring tradition of online programs. It seeks to transform its offer toward blended learning in alignment with Decree 1330 of the Ministry of Education [44].

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the university shut down all in-person activity in 2020. Like many other schools and universities across the globe, the university began offering virtual courses. Their goal was to provide learning experiences enhanced by technology and have flexible and adaptable academic environments. By the spring semester of 2021, the university offered courses in various modalities, including blended, live remote delivery and online asynchronous courses. The university became interested in better understanding students’ abilities to engage in multiple online modalities to improve and offer classes in each of these modalities even after the pandemic.

3.2. Data Collection

The data in this study were collected via survey to better understand current student needs and university efforts to support student engagement in online and blended teaching modalities (see Appendix A). In this paper, we focus on barriers students experienced in online/blended courses and their perceptions of the university’s support to support their engagement. The survey was developed, translated into Spanish, piloted with students, and overseen by university administrative stakeholders. The survey items asked students questions relating to academic success, academic engagement, and academic support for engagement as defined in the ACE framework. It also included a section with questions regarding students’ demographic information. It concluded with an open-ended question for students to leave any additional comments they wanted to share on how the university could better support their academic engagement in their online and hybrid courses (See survey items in Appendix A).

To test basic reliability for the overall survey, Cronbach’s Alpha was 0.969, which is very high. The survey data set was too large to analyze and report on with one academic paper. Another paper that is in progress contains details of the psychometric properties of the instrument and model using CFA analysis, but that reporting is beyond the scope and purpose of this article. Table 1 shows the specific data we used from the survey to answer our research questions and address the purposes of this study.

Table 1.

Data collected from the university survey.

3.3. Data Analysis

To analyze the data, we used descriptive statistics to represent the quantitative findings. We also conducted a qualitative thematic analysis of the open-ended question using Attride-Stirling’s approach to organizing findings into thematic networks [45]. See Table 2 for an overview of our data analysis.

Table 2.

Research questions, data collected, and data analysis methods.

3.3.1. Descriptive Statistics

In our quantitative analysis, we report means, standard deviations, and some percentages. This basic analysis helped us understand how well students felt the university supported their academic engagement in three dimensions: affective engagement, behavioral engagement, and cognitive engagement [18]. It also helped us understand which barriers students were facing and the relative influence of individual barriers.

3.3.2. Thematic Analysis of Open-Ended Question

Our qualitative thematic analysis helped us better understand the barriers students faced regarding receiving engagement support from the institution. We initially open-coded each response and grouped common codes into organizing themes. We further grouped these organizing themes into global themes according to the various dimensions of academic engagement (affective, behavioral, and cognitive) and any other significant categories that came out in the responses unrelated to the types of engagement. One researcher coded all the answers first and developed a coding structure. A second researcher then independently coded the responses using the same coding structure the first researcher developed. They found that they had a 97% interrater agreement among the global codes. After both researchers independently coded the data, they discussed and agreed on any discrepancies.

3.4. Ethical Considerations

Partners at the university underwent an ethical review process at their institution. Other researchers received archival data to analyze that had no personally identifiable information.

4. Results

We organized the results according to the two research questions we addressed in this study.

4.1. Question #1: How Do Students Feel the Institution Is Supporting Their Academic Engagement for Online and Blended Learning (Including Affective, Behavioral, and Cognitive Dimensions)?

The survey included 12 statements that asked students to rate their agreement with their perceived level of personal academic engagement in their online and blended courses within each type of indicator for engagement: Affective (4 items), Behavioral (4 items), Cognitive (4 items). Results showed that the average for student engagement was about the same, with affective engagement somewhat lower than behavioral and cognitive engagement (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Average of each type of academic engagement (scale: 1 = strongly disagree (not engaged) to 6 = strongly agree (engaged)) (n = 1295).

The survey then included 24 statements asking students to rate their agreement with the level of institutional support they received to help them engage academically within each type of engagement: Affective (9 items), Behavioral (9 items), Cognitive (6 items). The results were consistent with students’ perceived engagement levels (See Table 4).

Table 4.

Averages of each type of support for academic engagement (scale: 1 = strongly disagree (does not support engagement) to 6 = strongly agree (supports engagement)) (n = 1295).

Students rated their agreement with the level of specific support they received in subcategories within each primary category (affective, behavioral, cognitive). In each subcategory, the mean was about the same (4.3–4.5), possibly indicating that students generally feel well supported across engagement types or do not differentiate between different types of support (see Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7). Within the affective engagement indicator, students rated their agreement with the level of support they received regarding facilitating communication (3 items), developing relationships (3 items), and instilling excitement for learning (2 items) (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Descriptive statistics of affective support elements (scale: 1 = strongly disagree (does not support engagement) to 6 = strongly agree (supports engagement)) (n = 1295).

Table 6.

Descriptive statistics of behavioral support elements (scale: 1 = strongly disagree (does not support engagement) to 6 = strongly agree (supports engagement)) (n = 1295).

Table 7.

Descriptive statistics of cognitive support elements (scale: 1 = strongly disagree (does not support engagement) to 6 = strongly agree (supports engagement)) (n = 1295).

For behavioral engagement, students rated their agreement with the level of support they received for troubleshooting and orienting (3 items), organizing and managing their coursework (3 items), and monitoring and encouraging progress (3 items) (see Table 6).

For cognitive engagement, students rated their agreement with the level of support they received in instruction (3 items) and collaborating (3 items) (see Table 7).

In Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7 (above), very few students were extremely unhappy with the support they received in the areas of affective, behavioral, and cognitive support, but about one-quarter of the students scored a three or lower. This number is still too large for university stakeholders to be content with, which provides evidence that we must dig deeper into the barriers students are facing to better understand what causes dissatisfaction among some students.

4.2. Question #2: What Are the Barriers to Student Academic Engagement for Online and Blended Learning at the Institutional Level?

4.2.1. Descriptive Statistics

The survey also asked students to report on the external barriers that they experience as university students in online and blended courses that prevent them from fully engaging academically. Their reported barriers included transportation, Internet access, computer access, affordable housing, technical support, family environment, and work schedule. The primary purpose for asking students about these barriers was to understand how the university can better support students to engage academically in their online and blended courses. Table 8 shows how many students rated each type of barrier and the level of barrier it was for them. Transportation appeared to be the greatest barrier, with 442 (34%) participants rating it between 4–6 on the scale (see Table 8).

Table 8.

Descriptive statistics of barriers (scale: 1 = not a barrier to 6 = high barrier) (n = 1295).

Overall, the mean for each barrier is fairly low, which may indicate that for the majority of students, these barriers do not inhibit their ability to engage in their learning. However, 66% of all participants experienced at least one barrier as a student. In comparison, almost half (46%) of participants indicated they experienced more than one barrier as a student, and 31% experienced three or more barriers (See Table 9).

Table 9.

Students with multiple barriers (n = 1295).

4.2.2. Qualitative Findings

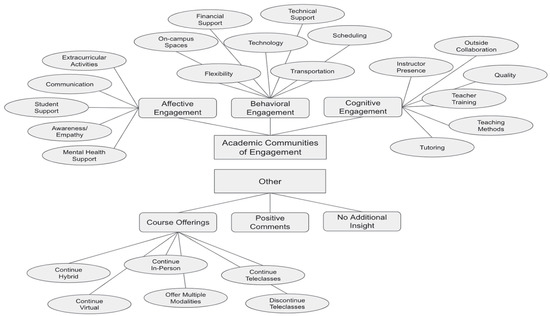

The thematic network that we developed through qualitative analysis is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Thematic network.

The findings from the qualitative thematic analysis are presented in Table 10. Participant responses to the open-ended question: “Please share any comments or ideas you have about how the university can better support your academic engagement in online/blended environments” were coded into organizing themes and then grouped into global codes based on the type of support they needed. The global codes included affective engagement, behavioral engagement, cognitive engagement, course offerings, positive comments, and “other.” 291 (22.4%) of the comments indicated a need for greater support for behavioral engagement, and 241 (18.6%) requested greater support for cognitive engagement, while only 161 (12.4%) of codes indicated a need for support for affective engagement (see Table 10).

Table 10.

Number and example of each type of global support code.

Within the category of affective engagement, 74 (46%) of the comments regarded the need for more awareness and empathy for individual student circumstances, and 41 (25%) discussed the need for more general student support that is easily accessible to students. 20 (13%) of respondents also indicated the need for better mental health support in the university community (see Table 11).

Table 11.

Organizing themes for affective engagement (n = 161).

The most prominent codes in the behavioral engagement category were technology and flexibility, with 69 (24%) of comments addressing the need for improved technology on campus, and 65 (22%) comments regarding the need for greater flexibility with assignments and due dates in online and blended courses (see Table 12).

Table 12.

Organizing themes for behavioral engagement (n = 291).

Over half of the responses within the cognitive engagement category (66%) addressed the need for different teaching methods in the online and blended course environments. In addition, 41 (17%) of respondents wished they had better-trained teachers to teach in the online and blended settings (See Table 13).

Table 13.

Organizing themes for cognitive engagement (n = 241).

Concerning course offerings, participants had varying opinions regarding which type of course modalities should be offered. However, 101 (60%) of respondents suggested that most courses fully return to the in-person modality (See Table 14).

Table 14.

Organizing themes for course offerings (n = 169).

Both the barrier data and the open-ended responses indicate that the students focused mainly on the need for improvement in support of behavioral engagement. Finding ways to further eliminate each type of barrier and provide increased support within each domain (affective, behavioral, cognitive) should also be considered.

5. Discussion

The central purpose of this study was to better understand how institutions support university students’ academic engagement in online and blended courses, identify barriers that exist for university students in online and blended courses, and what institutional support can be provided to mitigate these barriers for students. The study results reveal that most students experience barriers, and many experience more than one barrier. Following the guidelines provided by the ACE framework, institutions can potentially alleviate many of these barriers by implementing specific support systems for their students in online and blended courses. Significant takeaways from the findings of this study include:

- Transportation and Internet access were the most common barriers that students experience. Universities with similar barriers may want to first focus on behavioral engagement support and ensure all students have the access they need to have the ability to engage academically in online and blended courses.

- The greatest need for affective support is more empathy and understanding from instructors and faculty.

- Proper teaching methods for online and blended learning settings are vital to helping students be able to engage cognitively in online and blended learning courses.

One observation from these findings is that while this study focused on the university as a whole, it may be essential for universities and learning programs to look at different types of learners within a student population to develop adequate learning support. For example, while there was no significant difference between the students’ perceptions of the different types of support (affective, behavioral, cognitive) they receive from the institution, the standard deviations in each area seem large. This result could indicate that there is a wide variance in what students are experiencing at the university. Rather than focus on the entire student population, it may be more beneficial to understand specific types of students or learning contexts that are less academically engaged than the university as a whole. The findings also revealed that many students experience multiple barriers to fully engaging in online and blended learning courses. A large portion of students experience multiple barriers, while others experience only one or no barrier to their learning. Understanding the specific situations of students experiencing these different levels of barriers is crucial. It may be one way practitioners can work towards providing institutional support that fits the needs of the different groups, rather than aiming for a “one-size fits all” approach.

Institutions may consider looking at the average scores of students experiencing two or more barriers to understand their situation better. Understanding this information would help a university or learning program know how to focus their energy on improving the institutional support for academic engagement for more specific demographics rather than focusing everywhere at once [39,40,43,46]. Understanding these barriers through the lens of the ACE framework can also help practitioners determine concrete solutions to eliminate many of these barriers and enable students to become more fully engaged in the online and blended course modalities [18].

A second observation from these findings is that behavioral engagement support seems to be the most needed type of support to help students overcome the most prevalent barriers of this study. The need for behavioral engagement support was the most extensive global code in our thematic network—many student responses corresponded with the types of barriers they experienced. Student responses indicated a need for greater financial support, greater flexibility in scheduling, technical assistance, and transportation assistance. These suggestions from students align with many of the barriers they were experiencing, such as difficulty finding affordable housing, difficulty getting transportation to school, challenges with the Internet, and lack of technology and resources. Students need to be behaviorally engaged before they can engage cognitively and affectively. Behavioral engagement gives students the skills to access an online course and know how to navigate it [18,21]. As such, an institution’s top priority for providing academic engagement support to students could first be to ensure that all students are behaviorally engaged. The ACE framework gives practical suggestions for supporting this type of engagement, including troubleshooting, monitoring progress, organizing physical learning spaces, learning self-regulation strategies, and minimizing distractions [18,22,47,48].

An additional observation the thematic analysis revealed is that students not only lack support for behavioral engagement, but cognitive and affective engagement as well. As noted in the findings, 74% of the responses regarding affective support indicated a greater need for more awareness and empathy regarding student circumstances. Research on affective engagement shows that this is a critical component of fully engaging academically [18,27,28,29]. Universities can primarily support this by facilitating effective online communication [18], which often requires a different skill set than in-person communication [20,30]. Additionally, students indicated a need for easier access to general student support services and mental health resources. As Garrison et al. note, cultivating a community online is key to providing this affective support [31].

Regarding cognitive engagement, participants’ most prominent need was teaching methods specific to online and blended learning, as well as instructors who are better trained in online and blended learning modalities to teach these classes. We know from online and blended learning research that proper teaching methods and techniques are critical for the success of this type of learning. Improving the quality of online and blended courses and ensuring instructors are properly trained to teach these types of classes could significantly influence the ability of students to engage cognitively with the material [33,49]. Last, participants’ suggestion for courses to return face-to-face most likely supports the previous findings that there is not currently adequate support for these types of classes. While there may be specific courses better suited for the traditional face-to-face teaching model, implementing the proper support at the institutional level for online and blended courses could mitigate many of the issues and barriers students are experiencing in these classes.

Limitations

This study includes some limitations. First, because the survey instrument was voluntary, we only received responses from a portion of the university’s student population. The results may not be fully representative of the entire study body. Likewise, the results may also not be representative of other universities. Because each university has unique needs, it may be difficult to generalize these specific results and suggestions and apply them to different settings. For example, the barriers students reported on are particular to the needs of students in this region and may not directly apply to all other areas of the world. Instead, this study can serve as a model for other universities to follow to find the unique needs of their students. An additional limitation may be the lack of in-depth qualitative data. Because this study focused on covering breadth instead of depth, we may need more qualitative data to understand better the barriers students face in their online and blended courses and how institutions can provide adequate support.

6. Conclusions

The main objective of this study was to understand how institutions support university students’ academic engagement in online and blended courses (RQ1) and identify the barriers that may exist for university students in online and blended courses (RQ2) in order to better understand how institutional support may alleviate these barriers. Our findings revealed that students generally feel adequately supported by their institution; however, there are still several students that lack the necessary support they need to succeed academically in their online and blended courses. To understand how to support these students, we must first understand the barriers they are experiencing that inhibit them from fully engaging academically. Our data have shown that students are experiencing barriers to their learning, with many experiencing more than one obstacle. There is insufficient institutional support for many to overcome these barriers and engage fully in online and blended learning.

6.1. Implications for Practitioners

Following the guidelines provided by the ACE framework [18] institutions can alleviate many of these barriers by implementing specific support systems for their students’ online and blended courses. While the findings may not apply directly to other universities whose students experience different barriers, this study can serve as a model for administrators and institutions to use to learn how to better support students in online and blended courses at the institutional level.

6.2. Implications for Future Research

To better understand how institutions can support students in online and blended learning environments, future research should look more in-depth at learners with specific barriers. This could help institutions know exactly what causes certain barriers in different types of learners and uncover more specific solutions for mitigating those barriers for particular populations. Other groups of students that researchers may want to investigate include students’ areas of study, school level, gender, age, and social class. Understanding each of these different groups and how they experience barriers may also reveal insights that could help institutions know how to support all types of learners. Additional qualitative studies would also be beneficial to better understand students’ experiences and specific needs of different types of students with varying levels of barriers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.T., C.R.G., D.M.P.C. and A.M.M.A.; methodology, S.T., C.R.G., D.M.P.C. and A.M.M.A.; data collection, A.M.M.A. and D.M.P.C.; data coding, S.T., D.M.P.C. and A.M.M.A.; writing—original draft preparation, S.T.; writing—review and editing, S.T., C.R.G., D.M.P.C. and A.M.M.A.; visualization, S.T.; supervision, C.R.G.; project administration, C.R.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

We hereby certify that the study entitled Institutional ACE Survey 1.0: University Support for Academic Engagement, developed during the second semester of 2021 was conducted under institutional guidelines of data protection and confidentiality, reviewed by the General Secretary Office at UNAB and duly considered in the MOU signed by UNAB and BYU on 10 August 2021 and registered with the code 150826 at Alfanet, the university’s information system, on 7 September 2021. Please note that UNAB encourages institutional studies for strategic purposes that will benefit our student services. As such, this study was conducted by the Direction of Academic Affairs, a unit supervised by the Academic Vice president, with the approval of the President’s Office. These institutional studies have a different process than the ones implemented by faculty and researchers affiliated to the Direction of Research. Therefore, the review of ethical use of information and anonymity of the students who responded to the survey, was carefully taken into consideration and approved by the Academic Vice president, General Secretary and Director of Academic Affairs. If you need further information, you can contact us at viceacademic@unab.edu.co. BYU researchers worked with UNAB to help analyze the anonymized existing data set.

Informed Consent Statement

In compliance with the provisions on Personal Data Protection, the Autonomous University of Bucaramanga NIT 890.200.499-9 requires your free, prior, express, unequivocal, and duly informed authorization to carry out the collection, registration, storage, storage, use, circulation, deletion, processing, compilation, exchange, updating, and in general the treatment of all the data that will be requested in this survey. The purposes of the survey are (i) to measure the experience of the students under the concept of Academic Communities of Engagement in hybrid/virtual environments, (ii) its use for the creation of reports and statistical reports within the institution, and (iii) circulation of anonymous reports to allied institutions; as well as the use for presentation to national and international entities, private and public on the issues that are related to this survey. Some of the data requested here correspond to sensitive data, such as gender and socioeconomic status. You are not obliged to provide such information. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Archival data for the research was provided by Universidad Autónoma de Bucaramanga (UNAB) and are not publicly available.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Survey Instrument

Questions about Support Community at the University (e.g., Instructors, Advisors, Classmates)

STEM: I have a support community at the university (e.g., instructors, advisors, classmates) that can help me to… (1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree).

| Affective Support Elements | Survey Items |

|---|---|

| Facilitating Communication |

|

| Developing Relationships |

|

| Instilling Excitement for Learning |

|

STEM: Rate your agreement with the following statements about your online learning experience this past academic year (1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree).

| Behavioral Support Elements | Survey Items |

|---|---|

| Troubleshooting & Orienting |

|

| Organizing & Managing |

|

| Monitoring & Encouraging Progress |

|

STEM: Rate your agreement with the following statements about your online learning experience this past academic year (1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree).

| Cognitive Support Elements | Survey Items |

|---|---|

| Instructing |

|

| Collaborating |

|

Appendix A.2. Barriers Data

STEM: Identify how much of a barrier each of the following are to your participation in your online learning. (Scale: 0 = no barrier to 6 = very large barrier)

- Transportation difficulties (cost, access, travel time, etc.)

- Internet access/speed in my home

- Access to a good computer

- Access to affordable housing in the metropolitan area

- Access to technical support

- Family environment (childcare, care for parents, etc.)

- Work schedule complications

References

- Fredricks, J.A.; Blumenfeld, P.C.; Paris, A.H. School Engagement: Potential of the Concept, State of the Evidence. Rev. Educ. Res. 2004, 74, 59–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrie, C.R.; Halverson, L.R.; Graham, C.R. Measuring Student Engagement in Technology-Mediated Learning: A Review. Comput. Educ. 2015, 90, 36–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reschly, A.L.; Christenson, S.L. Jingle, Jangle, and Conceptual Haziness: Evolution and Future Directions of the Engagement Construct. In Handbook of Research on Student Engagement; Christenson, S.L., Reschly, A.L., Wylie, C., Eds.; Springer US: Boston, MA, USA, 2012; pp. 3–19. ISBN 978-1-4614-2017-0. [Google Scholar]

- Macfarlane, B.; Tomlinson, M. Critical and Alternative Perspectives on Student Engagement. High Educ. Policy 2017, 30, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, E.A.; Pitzer, J.R. Developmental Dynamics of Student Engagement, Coping, and Everyday Resilience. In Handbook of Research on Student Engagement; Christenson, S.L., Reschly, A.L., Wylie, C., Eds.; Springer US: Boston, MA, USA, 2012; pp. 21–44. ISBN 978-1-4614-2017-0. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Eliyahu, A.; Moore, D.; Dorph, R.; Schunn, C.D. Investigating the Multidimensionality of Engagement: Affective, Behavioral, and Cognitive Engagement across Science Activities and Contexts. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2018, 53, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halverson, L.R.; Graham, C.R. Learner Engagement in Blended Learning Environments: A Conceptual Framework. Online Learn. 2019, 23, 145–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, D.R.; Arbaugh, J.B. Researching the Community of Inquiry Framework: Review, Issues, and Future Directions. Internet High. Educ. 2007, 10, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pianta, R.C.; Hamre, B.K.; Allen, J.P. Teacher-Student Relationships and Engagement: Conceptualizing, Measuring, and Improving the Capacity of Classroom Interactions. In Handbook of Research on Student Engagement; Christenson, S.L., Reschly, A.L., Wylie, C., Eds.; Springer US: Boston, MA, USA, 2012; pp. 365–386. ISBN 978-1-4614-2017-0. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, C.-M.; Kuh, G.D. Adding Value: Learning Communities and Student Engagement. Res. High. Educ. 2004, 45, 115–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.; Cui, Y.; Zhou, W. Relationships between Student Engagement and Academic Achievement: A Meta-Analysis. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2018, 46, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, E.; Furrer, C.; Marchand, G.; Kindermann, T. Engagement and Disaffection in the Classroom: Part of a Larger Motivational Dynamic? J. Educ. Psychol. 2008, 100, 765–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, F.; Borup, J. Online Learner Engagement: Conceptual Definitions, Research Themes, and Supportive Practices. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 57, 162–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reschly, A.L. Interventions to Enhance Academic Engagement. In Student Engagement; Reschly, A.L., Pohl, A.J., Christenson, S.L., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 91–108. ISBN 978-3-030-37284-2. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman-Perrott, L.; Burke, M.D.; Zhang, N.; Zaini, S. Direct and Collateral Effects of Peer Tutoring on Social and Behavioral Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis of Single-Case Research. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 2014, 43, 260–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhow, C.; Graham, C.R.; Koehler, M.J. Foundations of Online Learning: Challenges and Opportunities. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 57, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archambault, L.; Leary, H.; Rice, K. Pillars of Online Pedagogy: A Framework for Teaching in Online Learning Environments. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 57, 178–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borup, J.; Graham, C.R.; West, R.E.; Archambault, L.; Spring, K.J. Academic Communities of Engagement: An Expansive Lens for Examining Support Structures in Blended and Online Learning. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2020, 68, 807–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shea, P.; Richardson, J.; Swan, K. Building Bridges to Advance the Community of Inquiry Framework for Online Learning. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 57, 148–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInnerney, J.M.; Roberts, T.S. Online Learning: Social Interaction and the Creation of a Sense of Community. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2004, 7, 73–81. [Google Scholar]

- de la Varre, C.; Irvin, M.J.; Jordan, A.W.; Hannum, W.H.; Farmer, T.W. Reasons for Student Dropout in an Online Course in a Rural K–12 Setting. Distance Educ. 2014, 35, 324–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michinov, N.; Brunot, S.; Le Bohec, O.; Juhel, J.; Delaval, M. Procrastination, Participation, and Performance in Online Learning Environments. Comput. Educ. 2011, 56, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviatt, D.R.; Graham, C.R.; Davies, R.S.; Borup, J. Online Student Use of a Proximate Community of Engagement in an Independent Study Program. Online Learn. 2018, 22, 223–251. [Google Scholar]

- Roksa, J.; Kinsley, P. The Role of Family Support in Facilitating Academic Success of Low-Income Students. Res. High Educ. 2019, 60, 415–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrami, P.C.; Bernard, R.M.; Bures, E.M.; Borokhovski, E.; Tamim, R.M. Interaction in Distance Education and Online Learning: Using Evidence and Theory to Improve Practice. J. Comput. High Educ. 2011, 23, 82–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harms, C.M.; Niederhauser, D.S.; Davis, N.E.; Roblyer, M.D.; Gilbert, S.B. Educating Educators for Virtual Schooling: Communicating Roles and Responsibilities. J. Commun. 2006, 16, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice-Hall series in social learning theory; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986; ISBN 978-0-13-815614-5. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wigfield, A.; Eccles, J.S. Expectancy–Value Theory of Achievement Motivation. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borup, J.; Stimson, R.J. Responsibilities of Online Teachers and On-Site Facilitators in Online High School Courses. Am. J. Distance Educ. 2019, 33, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, D.R.; Anderson, T.; Archer, W. Critical Inquiry in a Text-Based Environment: Computer Conferencing in Higher Education. Internet High. Educ. 1999, 2, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, W. Beyond Online Discussions: Extending the Community of Inquiry Framework to Entire Courses. Internet High Educ. 2010, 13, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, C.R.; Borup, J.; Short, C.; Archambault, L. K-12 Blended Teaching: A Guide to Personalized Learning and Online Integration; Independently Published; EdTechBooks.org: Provo, UT, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hillman, D.C.A.; Willis, D.J.; Gunawardena, C.N. Learner-interface Interaction in Distance Education: An Extension of Contemporary Models and Strategies for Practitioners. Am. J. Distance Educ. 1994, 8, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borup, J.; Stevens, M.A.; Waters, L.H. Parent and Student Perceptions of Parent Engagement at a Cyber Charter High School. Online Learn. 2015, 19, 69–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T.; Liam, R.; Garrison, D.R.; Archer, W. Assessing Teaching Presence in a Computer Conferencing Context. J. Asynchronous Learn. Netw. 2001, 5, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conceição, S.C.O.; Lehman, R.M. Students’ Perceptions about Online Support Services: Institutional, Instructional, and Self-Care Implications. Int. J. e-Learn. 2016, 15, 433–443. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, C.G. The Persistence and Attrition of Online Learners. Sch. Leadersh. Rev. 2017, 12, 47–58. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, C.R.; Woodfield, W.; Harrison, J.B. A Framework for Institutional Adoption and Implementation of Blended Learning in Higher Education. Internet High. Educ. 2013, 18, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, W.W.; Graham, C.R.; Spring, K.A.; Welch, K.R. Blended Learning in Higher Education: Institutional Adoption and Implementation. Comput. Educ. 2014, 75, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanovas, I. The Impact of Communicating Institutional Strategies in Teacher Attitude about Adopting Online Education. In Proceedings of the International Conference on e-Learning, Kelowna, BC, Canada, 27–28 June 2011; pp. 62–71. [Google Scholar]

- Casanovas, I. Exploring the Current Theoretical Background About Adoption Until Institutionalization of Online Education in Universities: Needs for Further Research. Electron. J. E-Learn. 2010, 8, 73–84. [Google Scholar]

- Garrison, D.R.; Kanuka, H. Blended Learning: Uncovering Its Transformative Potential in Higher Education. Internet High. Educ. 2004, 7, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decreto 1330 de Julio 25 de 2019. Available online: https://www.mineducacion.gov.co/portal/normativa/Decretos/387348:Decreto-1330-de-julio-25-de-2019 (accessed on 11 August 2022).

- Attride-Stirling, J. Thematic Networks: An Analytic Tool for Qualitative Research. Qual. Res. 2001, 1, 385–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, T.; Warschauer, M. Equity in Online Learning. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 57, 192–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrix, N.; Degner, K. Supporting Online AP Students: The Rural Facilitator and Considerations for Training. Am. J. Distance Educ. 2016, 30, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repetto, J.; Cavanaugh, C.; Wayer, N.; Liu, F. Virtual High Schools: Improving Outcomes for Students with Disabilities. Q. Rev. Distance Educ. 2010, 11, 91–104. [Google Scholar]

- Lalonde, C. Facilitation in Digital Learning Environments; EdTech Books: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).