Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic made the experience of being a first-year freshman college student unique. This study aims to analyze the hopes and fears of these students concerning their current life and future goals. Participating students completed the Hopes & Fears questionnaire. Results showed that students’ hopes and fears were mainly connected with domains of education and the global/collective dimension, followed by personal and family members’ health. Two new categories emerged, self-fulfillment and solidarity, reflecting the importance of the contextual dimension that these students were navigating. The findings of the current study contribute to the research of college students’ hopes and fears towards their future and accounts for the analyses of this topic as we progress to a post-pandemic phase.

1. Introduction

In Portugal, as in other European countries, the expansion of higher education has attracted research that focuses on the importance of successfully integrating students that are enrolled in college for the first time [1]. Because enrolling in college for the first time entails challenges and opportunities for personal development and growth, adaptation to college life may differ, depending on the contexts in which they occur. Thus, making the transition and subsequent adaptation to higher education in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic adds complexity to this process.

The changes made in higher education, resulting from sanitary measures caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, placed students at home, in a digital learning environment, transferring classes, meetings, assessments, and socializing with peers into an online context. Initially portrayed as an equalizing learning environment [2], research rapidly found that the pandemic had the potential to exacerbate inequalities in education. Differences in access to broadband internet connections, in technological assets, in adequate living spaces to attend on-line classes, and in digital literacy skills, among other things, brought additional constrains to an effective experience of on-line learning experience for many students [3]. Moreover, the social crisis related to the COVID-19 pandemic also had impacts on students’ families and social relations.

Some authors claim that the disruption in the educational and personal lives of students, caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, might last and have impacts on both their academic and professional aspirations [4]. Others have a more optimistic approach and call attention to the fact that the so called “COVID-19 generation” might be very diverse and copped differently with the pandemic [5]. This study aims to address this gap in the literature by analyzing the hopes and fears of students who enrolled in higher education for the first time during the COVID-19 pandemic.

1.1. Being a First-Year Freshman College Student

Some authors claim that freshmen are exposed to two major life events that can have effects on their well-being. On one hand, they are facing the transition from adolescence to emerging adulthood [6] and, on the other hand, they have to cope with the adjustment to college [7]. Academic context factors, such as the number and diversity of academic tasks to be performed, accessibility of study materials, and good interaction with professors, together with individual factors, such as the ability to perform tasks and assignments independently, have been identified as key dimensions to successfully adjust to college [8]. Other authors emphasize the importance of social relations with peers and professors [9]. Additionally, research on undergraduate students found that they often face financial, relational, or academic issues that can impact students’ stress levels [10,11].

1.2. Being a First-Year Freshman College Student in the Time of the COVID-19 Pandemic

Enrolling for the first time in higher education in a pandemic year, at a time when the experience of life in confinement and under a state of emergency and calamity has been ongoing for months, can posit some additional challenges for freshmen students. Research carried out with higher education student samples during the COVID-19 pandemic found that students have experienced high levels of psychological distress, such as increased anxiety and depressive symptoms and poor sleep quality [12]. Considering that the educational institution is the focal point of multiple activities and social interactions, the transference of teaching activities to an online setting dramatically changed this context. The isolation of students and unequal conditions for completion of online courses, to which socio-economic and family strain were added, impacted the health and well-being of many students [13]. Gonzalez-Ramirez et al. [14] describe students’ exhaustion and disbelief in education because of the pandemic context. Although most students, due to their age, were not initially considered part of the at-risk population, they suffered significantly from the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, both in their daily lives and in their expectations for the immediate and distant future [15]. Aristovnik et al. [15] found feelings such as boredom, frustration, anxiety, hopelessness, or anger, but also feelings of hope and joy, suggesting that apparently contradictory feelings might have emerged during the pandemic. Equally affected, the network of social relationships has changed with physical distance, although alternative ways have been used to keep regular contacts with family members and friends [15].

However, the global context of the pandemic and the uncertainty in the face of the unknown (new virus, SARS-CoV-2 or COVID-19) also raised concerns regarding the health of family members, with many students facing financial constrains due to family reduced income, with situations of layoff or unemployment of parents, which caused uncertainty and distress regarding their future and the continuity of an academic path [4]. A study by Aristovnik et al. [15] found a concern regarding future professional careers and academic advancement in more than 40% of students surveyed in 62 countries during the pandemic period. Despite these results, Aristovnik et al. [15] suggests that these students might have faced contradictory feelings, which underline the diversity of experiences that the pandemic created. Thus, in line with some authors, it should be considered that college students belong to the so called “Generation Y”, who have fixed ideation of their self-worth, influenced by the self-esteem movement [16] and, according to Twenge [17] present high levels of narcissism, over-confidence, and aversion to negative events. Given this scenario of the transition and adaptation to college during the COVID-19 pandemic and considering the personal characteristics of these life stage [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17], investigating the hopes and fears of first-year freshman college students towards their future life takes on greater relevance.

1.3. Future Orientation and “Hopes and Fears” of College Students

Seginer and Lens [18] stated that hopes for the future and goal-setting guide behaviors motivate people to engage in efforts towards the achievement of these goals. Other authors, such as Zaleski and Przepiórka [19], also endorse this assumption, reinforcing the idea that the more important the goal, the more persistent is the motivation to achieve it. Thus, understanding and addressing the hopes of first-year students in higher education could play a central role in ensuring that students have a future orientation regarding their future life [20]. As Zimbardo and Boyd [21] claim, thinking about the future offers ground for young adults to explore options and establish personal goals and to make plans for the future and commit to them. Therefore, future orientation drives young adult behavior in many life domains related school, jobs, family, and personal relations. Research using this framework showed that future-oriented students are more intrinsically motivated to engage in academic activities [22], while studies focused on employment found a link between thinking about the future and future employability [23]. Thus, thinking about the future and goal setting motivates behaviors that are oriented to give support to these aspirations and hopes. While hopes include aspirations and the goals to be achieved, fears comprise situations or things that need to be avoided, and both hopes and fears guide the behavior towards goal achievement [24].

This study adds to existing knowledge regarding the hopes and fears of emerging adults by investigating first-year student’ hopes and fears concerning their future. The purpose of this exploratory study was to analyze the self-reported representations that students develop regarding their future (i.e., which hopes/fears individuals have concerning their future) in a sample of freshman college students enrolled in higher education for the first time during the pandemic COVID-19.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample and Procedure

A total of 54 freshmen college students, enrolled in a Communication Sciences bachelor program, participated in this cross-sectional descriptive qualitative study. As a criteria to participate in the study, students had to be enrolled in higher education for the first time. Participants’ mean age was 19.28 years (SD = 1.92), and they were mainly female (83%). Potential participants were informed of the study through an e-mail as part of voluntary extra coursework. The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki for voluntary participation and confidentiality of the data. A weblink for the online survey version of the questionnaire was sent to the students in November 2020, and voluntary participation was requested. Participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Privacy and confidentiality of data were assured. Eligible participants were pursuing a full-time undergraduate program and were enrolled in that program and institution for the first time. A de-identified database was part of the data analysis.

2.2. Measure

Participants responded to the Hopes & Fears Questionnaire (HFQ) by Fonseca et al. [25], which is an open-ended measure that assesses thematic content (i.e., which hopes/fears individuals have concerning their future). After filling out a short sociodemographic questionnaire, students were asked to indicate which hopes and fears they had for their future (a maximum of 10 each). The answers’ content was classified into specific categories or life domains [25].

2.3. Data Analysis

Adopting a thematic approach [26], the self-reported participants’ hopes and fears regarding their future were classified into specific categories or life domains, in line with Fonseca et al. [25]. The analysis involved an inductive approach using qualitative content. All hopes and fears were copied by the researchers to create two separate files. Both researchers independently clarified the overall data and identified the main themes and classified the information according to the original categories of the Hopes & Fears Questionnaire. Information for each category was then compared and discussed by the two researchers in order to arrive at common grounded categories for hopes and fears.

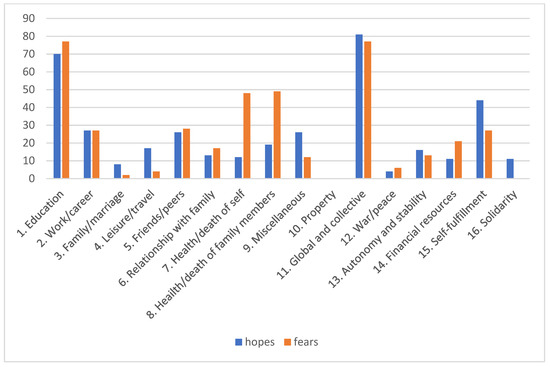

After determining the salience of each life domain, relative frequency scores (the number of hopes/fears per category) were indicated for the fourteen categories (1. Education, 2. Work/career, 3. Family/marriage, 4. Leisure/travel, 5. Friends and peers, 6. Relationships with family, 7. Health/death of self, 8. Health/death of family members, 9. Miscellaneous, 10. Property, 11. Global and collective, 12. War/peace, 13. Autonomy and stability, and 14. Financial resources). Because some participants reported hopes and fears that could not fit the original categories, two new categories were created related to self-fulfillment and hopes related to solidarity. The original category “property” received no answers in the present study.

3. Results

A total of 409 hopes and 396 fears were reported. As presented in Figure 1, the most frequently mentioned hopes and fears were related to global/collective (e.g., hopes (n = 81): “The world will go back to normal”; fears (n = 77; e.g., “We may never get back to the old normal”), followed by education (e.g., hopes (n = 70; e.g., “Achieve positive results at university”; fears (n = 77; e.g., “That I can’t complete my academic goals, not being successful”). After, regarding hopes, the categories most mentioned were self-fulfillment (n = 44; e.g., “Being able to make sense again and define a life project, personal and professional”), work/career (n = 27; e.g., “To work on what I like”), friends/peers (n = 26; e.g., “Get along with my colleagues and friends in a ‘normal’ way”), miscellaneous (n = 26; e.g., “Getting a job that not only allows me to be financially independent, but also makes me feel fulfilled and happy”), health/death of family members (n = 19; e.g., “May my family and friends always be safe and not lack for anything, most importantly, health”), leisure/travel (n = 17; e.g., “Get to know the world and learn from different cultures”), autonomy and stability (n = 16; e.g., “Educate me better about politics so I can vote responsibly”), relationship with family (n = 13; e.g., “Being able to reunite the whole family, without worries”), health/death of self (n= 12; e.g., “Keep me healthy physically and psychologically”), financial resources (n = 11; e.g., “Organize my financial life to become independent”), solidarity (n = 11; e.g., “Getting help and helping others, volunteering”), family/marriage (n = 8; e.g., “Building a family, more specifically, having children”) and war/peace (n = 4; e.g., “To experience freedom again”).

Figure 1.

Descriptive data on hopes and fears per category.

Concerning fears, the most mentioned categories were health/death of family members (n = 49; e.g., “The new virus may kill or damage to someone close to me”), health/death of self (n = 48; e.g., “Not being able to control my anxiety and let it take hold of me”), friends/peers (n = 28; e.g., “Not being able to develop friendships in this new stage due to the current situation.”), work/career (n = 27; e.g., “That this situation affects my entry into the labor market”), self-fulfillment (n = 27; e.g., “I’m afraid of not being able to be happy”), financial resources (n = 21; e.g., “Not being able to earn my own income for my independence”), relationship with family (n = 17; e.g., “Having to be separated from my family due to COVID”), autonomy and stability (n = 13; e.g., “Not being able to be financially independent when I graduate and having to continue to depend on and burden my parents”), miscellaneous (n = 12; e.g., “Fear of life ending before my dreams come true”), war/peace (n = 6; e.g., “The freedom we knew, before the virus, may not be lived again so quickly”), leisure/travel (n = 4; e.g., “Not having Erasmus experience”) and family/marriage (n = 2; e.g., “Not being able to have children”).

4. Discussion

This study aimed to analyze the hopes and fears of freshmen students as they adapt to college during these unprecedent times of the COVID-19 pandemic. As such, global/collective was the most salient domain, for both hopes and fears, but with more hopes than fears. Concerning the category global/collective, a possible explanation for the high results in this category could be linked with the timeframe in which this research took place: November 2020. In fact, at the time data collection was carried out, not only was the SARS-CoV2 virus spreading around the globe, with cases raising at the country level, but also the scenario for having an effective vaccine was still uncertain. We believe this could have accounted for the high results in this category. Another possible explanation could be linked with the fact that Portugal shares a collectivist cultural feature [27], with a cultural orientation towards the group (towards the “we”, to the detriment of “I”) and an assumption of responsibility for the collective. This cultural feature, together with a political communication strategy at the country level that emphasized the impact of individual behavior on collectivism in the fight against the new virus [28], could have accounted for the high presence of reports for this category. However, further studies are needed to have a more complete understanding of the importance of cultural values in shaping hopes and fears about the future of higher education students.

The second most rated category was education. This is not a surprising result, with students presenting more fears than hopes. In fact, transition and adaption to college is, under normal circumstances, a life period where critical personal and relational adjustments are made, with this adjustment being stressful for many students, but it also brings positive expectations towards academic life and meeting new friends [1]. As such, positive expectations can coexist with some stressful events concerning academic adjustment in higher education. Considering the challenges related to the transition and adaptation to higher education during the pandemic, both hopes and fears related to the education category were expected. Also expected were that fears would surpass hopes because the reduced interaction with peers and professors, together with the changes in the learning environment mediated by technologies, brought additional challenges to all students and, in particular, to first-year college students.

Supporting the view that contextual factors play a role in the rise of hopes and fears [29], the following categories that received more reports were, in the case of fears, health/death of family members and health/death of self and friends/peers. This seems to illustrate the importance of the pandemic context and the health concerns around family, friends, and the self. This is an expected result in line with research that showed that concerns regarding health and safety were raised among young people at unprecedented levels [15]. Moreover, individuals with a strong collectivist orientation have a greater perception of other’s physical and psychological vulnerability [30]. Therefore, students with a high sense of belonging to their groups (family and peers) might present a high level of concern with the risks of COVID-19, not only for themselves but also for the health of others. The category self-fulfillment, a category that emerged in the present study, received more hopes than fears, reflecting that, despite all the adversity and life constrains caused by the pandemic that these students were facing, they sill show some optimism and have high hopes concerning their future life goals. This result is in line with previous research by Twenge [17] and Arnett [6] with samples in the same age groups. Another result, which refers to the work/career category, received few hopes and fears. These results can be analyzed in light of the contextual and age-related factors of the sample. In fact, they are first-year students that were just starting their academic path in higher education, and they were young emerging adults (i.e., mean age 19.28). Previous studies showed that, while young emerging adults tend to be more engaged in educational and friendship goals, as they progress from emerging to young adulthood, they engage in more work-related goals [31]. The results of the present study follow this line as more educational and friend/peer-related hopes and fears were reported, when compared to the hopes and fears reported for the work/career category.

Autonomy and stability also had few reports, with more hopes than fears. Previous studies carried out with samples of Portuguese emerging adults showed that autonomy was reported as an important marker to be socially considered as an adult [32]. Moreover, studies also showed that college educated Portuguese emerging adults expect to reach autonomy around theirs 30s, some years after the transition from school to the labor market [32]. In fact, stability has been reported as a problematic feature for Portuguese emerging adults due to the economic and work constrains that they face during their first years in the labor market [33]. This situation can explain why the students in this study do not often report hopes or fears related to this category. Concerning the category financial resources, it was interesting to note that, as expected, more fears than hopes were reported, but few fears were mentioned. While previous studies by Ranta, Dietrich, and Salmela-Aro [34] found that financial concerns were especially prominent in studies done with emerging adults during economic crises, it is important to note that, despite the fact that this is a different type of crise—a sanitary crisis—it can also lead to some social problems related to unemployment, and financial constrains due to layoff periods. In this study, this category is not frequently mentioned, probably because these students rely on their parents’ financial support and felt confident that the financial dimension was not a problem, despite the fact they also report very few hopes concerning this theme. Concerning the leisure/travel category, more hopes than fears were reported. This result can be explained by the fact that, due to the pandemic situation, travel restrictions were implemented, thus, travelling became more of a wish for the future. However, some fears were still reported that, in most of the cases, were related to travelling in the city or to visit family and relatives because, during the time this study was carried out, the virus was spreading at the country level. The category war/peace also received few reports, for both hopes and fears. Despite the fact that, as mentioned by Serido [35], the COVID-19 pandemic has major unpredictable economic, social, and political consequences, the students in this study did not seem concerned about this theme. The category solidarity received only statements concerning hopes. This is a category that emerged in the present study. In fact, it was clear that these students believed that it is important to develop forms of solidarity, especially when facing a global pandemic. Once again, the contextual factors might have played an important role in the arising of statements regarding the importance of the different forms of solidarity in order to better cope with the adversity linked to the pandemic situation. This result follows the assumption by Stok, Bal, Yerkes, and de Wit [36] that underlines the idea that the context of the pandemic allowed questioning regarding different forms of solidarities: intergenerational, between nations, and between population groups. It is also important to note that the family and marriage category received, regarding both hopes and fears, few reports. In fact, previous studies with Portuguese samples of young adults that invoked the importance of marriage and family (i.e., having their own family) found that marriage is not seen as an important standpoint for reaching adulthood, and being a parent is a role they foresee around their 30s, and only after being in work or having career stability [32,33]. The results of the present study seem to follow this trend, which could be exacerbated by the contextual factors of these young adults, being freshman college students, where raising a family and marriage can be perceived as life goals to be achieved later in life. The miscellaneous category comprised more hopes than fears and involved different areas related do general life goals, personal goals, and achievements, evoking some levels of optimism towards adulthood markers [32]. While in the study of Fonseca et al. [25] the property category had very few statements, in the present study they were completely absent. Contextual factors can also account for the explanation of why the property category was never mentioned. This seems to reflect that, in times of uncertainty, having property is seen by the students as less important or even not important at all in times of a health crisis.

Regardless of the importance of the results to have a better understanding of the hopes and fears of these students, this research is not without limitations. The small and convenient sample, the unbalanced gender representation in the sample, and the fact the students belonged to one single higher education institution and had enrolled in one single program make in necessary to recommend caution when interpreting the results. Additionally, some sociodemographic variables, such as the financial, residential, and health situation of the student and their families, could also have impacted their hopes and fears; thus, future studies should analyze the potential contribution of these dimensions. Another important limitation that should be stated is that we cannot assume that the hopes and fears of these students would be different if the assessment was made under a normal situation (e.g., without the COVID-19 pandemic); thus, interpretation of the current results should be carried out cautiously.

Despite its limitations, this study contributes to the deeper perspective of how the students that enrolled in higher education for the first time during the pandemic navigate through their days with hopes and fears regarding their current situation and future life. A better understanding of this target group could be beneficial for the improvement of integration and support efforts within the academic context, improving their sense of security for their personal goals in the post-pandemic life.

5. Conclusions

As research by Seginer and Lens [18] showed, thinking about the future accounts for the presence of motivational goals and projects in young adults. Furthermore, future orientation has been found to have positive effects on students’ academic goals [18]. While previous studies consistently found that first-time college enrolment entails challenges and opportunities for personal development and growth, the COVID-19 pandemic added complexity to this process, with some studies claiming that the disruption in the educational and personal lives of students, caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, might last and have an impact on the aspirations of the students [4]. This exploratory study aimed to analyze the hopes and fears of college freshman students who enrolled in college for the first time during the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite its exploratory nature, this study complements previous research on the hopes and fears of college students and on the expectations of college students during the COVID-19 pandemic by highlighting how first-year students express their hopes and fears regarding their future, during their first year in college during a pandemic. The results revealed that the categories global/collective and education were the most frequently mentioned by the students, indicating their expected concerns but also their positive expectations towards their academic life and collective well-being in the face of a pandemic. Furthermore, two new categories emerged. One more personal-centered, related to self-fulfillment, and the other focusing more on the relational dimension, the solidarity category. Overall, this study, in general, encountered the categories that were found in the study of Fonseca et al. [25], with the exception of the property category. It is also important to note that the categories found presented different configurations regarding the categories that received more statements, both for hopes and fears, and added two new categories, reflecting the specificity of the sample and the context of the study.

Despite the exploratory nature of this study, this is the first research, to our knowledge, that specifically asked freshmen students about their hopes and fears regarding the future as they were adapting to college life. Analyzing these expectations could provide insights into their thoughts about the future and more broadly as they navigate their years in college under a global health crisis. The hopes and fears of these students were collected in their second month of college enrollment during the pandemic, at the peak of uncertainty, and not only tell a story of prevalent fears, but also underline some optimism in their hopes. However, because their college experience will continue as the pandemic persists, the results found could, for higher education institutions, play a role in mitigating some of the possible negative effects of the pandemic on the aspirations of these students. Thus, higher education institutions could strengthen their programs to cater for students’ needs, taking into consideration their hopes and fears, in order to promote not only a better adjustment to college life but also provide skills to help them overcome some of the barriers that COVID-19 brought that might have particularly impacted the learning and socializing opportunities of the freshmen students.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.A.; methodology, C.A. and J.L.F.; formal analysis, C.A. and J.L.F.; writing—original draft preparation, C.A. and J.L.F.; writing—review and editing, C.A. and J.L.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Research data are not shared.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Araújo, A.; Almeida, L. Adaptação ao ensino superior: O papel moderador das expectativas acadêmicas. Educ. Rev. Cient. Educ. 2015, 1, 13–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Asfaw, E.; Guo, E.; Jang, S.; Komarivelli, S.; Lewis, K.; Sandler, C.; Mehdipanah, R. Students’ Perspectives: How Will COVID-19 Shape the Social Determinants of Health and Our Future as Public Health Practitioners? Health Educ. Behav. 2020, 47, 850–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boté-Vericard, J.J. Challenges for the educational system during lockdowns: A possible new framework for teaching and learning for the near future. Educ. Inf. 2021, 37, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aucejo, E.; French, J.; Araya, M.-P.; Zafar, B. The impact of COVID-19 on student experiences and expectations: Evidence from a survey. J. Public Econ. 2020, 191, 104271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolf, C.; Zacher, H. “The COVID-19 Generation”: A Cautionary Note. Work Aging Retire. 2020, 6, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, J.J. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am. Psychol. 2020, 55, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bland, H.W.; Melton, B.F.; Welle, P.; Bigham, L. Stress tolerance: New challenges for millennial college students. Coll. Stud. J. 2012, 46, 362–376. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, A.; Leckey, J. Do expectations meet reality? A survey of changes in first-year student opinion. J. Furth. High. Educ. 1999, 23, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.; Wertlieb, E. Do First-Year College Students’ Expectations Align with their First-Year Experiences? NASPA J. 2005, 42, 153–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, R.; Rideout, C. ‘It’s been a challenge finding new ways to learn’: First-year students’ perceptions of adapting to learning in a university environment. Stud. High. Educ. 2020, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandiran, M.; Dhanapal, S. Academic stress among university students: A quantitative study of generation Y and Z’s perception. Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2018, 26, 2115–2128. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, W.; Hu, T.; Hu, B.; Jin, C.; Wang, G.; Xie, C.; Chen, S.; Xu, J. Prevalence and correlates of PTSD and depressive symptoms one month after the outbreak of the COVID-19 epidemic in a sample of home-quarantined Chinese university students. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 274, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adnan, M.; Anwar, K. Online learning amid the COVID-19 pandemic: Students’ perspectives. J. Pedagog. Sociol. Psychol. 2020, 2, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Ramirez, J.; Mulqueen, K.; Zealand, R.; Silverstein, S.; Reina, C.; BuShell, S.; Ladda, S. Emergency Online Learning: College Students’ Perceptions during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Coll. Stud. J. 2021, 55, 29–46. [Google Scholar]

- Aristovnik, A.; Kerzic, D.; Ravselj, D.; Tomazevic, N.; Umek, L. Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Life of Higher Education Students: A Global Perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C. Carol Dweck revisits the growth mindset. Educ. Week 2015, 35, 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Twenge, J.M. Teaching generation me. Teach. Psychol. 2013, 40, 66–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seginer, R.; Lens, W. The motivational properties of future time perspective future orientation: Different approaches, different cultures. In Time Perspective Theory; Review, Research and Application: Essays in Honor of Philip G. Zimbardo; Stolarski, M., Fieulaine, N., Van Beek, W., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 287–304. [Google Scholar]

- Zaleski, Z.; Przepiórka, A. Goals need time perspective to be achieved. In Time Perspective Theory; Review, Research and Application: Essays in Honor of Philip G. Zimbardo; Stolarski, M., Fieulaine, N., Van Beek, W., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 323–335. [Google Scholar]

- Seginer, R. Defensive pessimism and optimism correlates of adolescent future orientation: A domain specific analysis. J. Adolesc. Res. 2000, 15, 307–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimbardo, P.G.; Boyd, J.N. Putting time in perspective: A valid, reliable individual-differences metric. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 77, 1271–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, J.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Lens, W.; Lacante, M. Placing motivation and future time perspective theory in a temporal perspective. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2004, 16, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, K.; Griffin, M.A.; Parker, S.K. Future work selves: How salient hoped-for identities motivate proactive career behaviors. J. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 97, 580–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmberg, L.E.; Norrgard, S. Adolescents’ ideas of normative life span development and personal future goals. J. Adolesc. 1999, 22, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, G.; Silva, T.; Paixão, P.; Cunha, D.; Relvas, P. Emerging adults thinking about their future: Development of the Portuguese Version of the Hopes and Fears Questionnaire. Emerg. Adulthood 2019, 7, 444–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seginer, R. Future Orientation. Developmental and Ecological Perspectives; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede Insights. Available online: https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison/portugal/ (accessed on 23 September 2021).

- Courtney, E.; Felig, R.; Goldenberg, J. Together we can slow the spread of COVID-19: The interactive effects of priming collectivism and mortality salience on virus-related health behaviour intentions. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2021, 61, 410–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurmi, J.-E. Socialization and self-development: Channeling, selection, adjustment, and reflection. In Handbook of Adolescent Psychology; Lerner, R.M., Steinberg, L., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004; pp. 85–124. [Google Scholar]

- Germani, A.; Buratta, L.; Delvecchio, E.; Mazzeschi, C. Emerging Adults and COVID-19: The Role of Individualism-Collectivism on Perceived Risks and Psychological Maladjustment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmela-Aro, K. Personal goals and well-being during critical life transitions: The four C’s—Channelling, choice, co-agency and compensation. Adv. Life Course Res. 2009, 14, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonça, M.; Andrade, C.; Fontaine, A.M. Transição para a idade adulta e adultez emergente: Adaptação do Questionário de Marcadores da Adultez junto de jovens Portugueses. Psychologica 2009, 51, 147–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, C. Transição para a Idade Adulta: Das Condições Sociais às Implicações Psicológicas. Análise Psicológica 2010, XXVIII, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranta, M.; Dietrich, J.; Salmela-Aro, K. Career and romantic relationship goals and concerns during emerging adulthood. Emerg. Adulthood 2014, 2, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serido, J. Weathering economic shocks and financial uncertainty: Here we go again. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2020, 41, 389–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stok, M.; Bal, M.; Yerkes, M.; de Wit, J. Social Inequality and Solidarity in Times of COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).