Measuring a University’s Image: Is Reputation an Influential Factor?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis

2.1. Concept of Image and Levels of Measurement

2.2. Reputation and Image

2.3. Measurement Scales for University Image

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample

3.2. Instrument

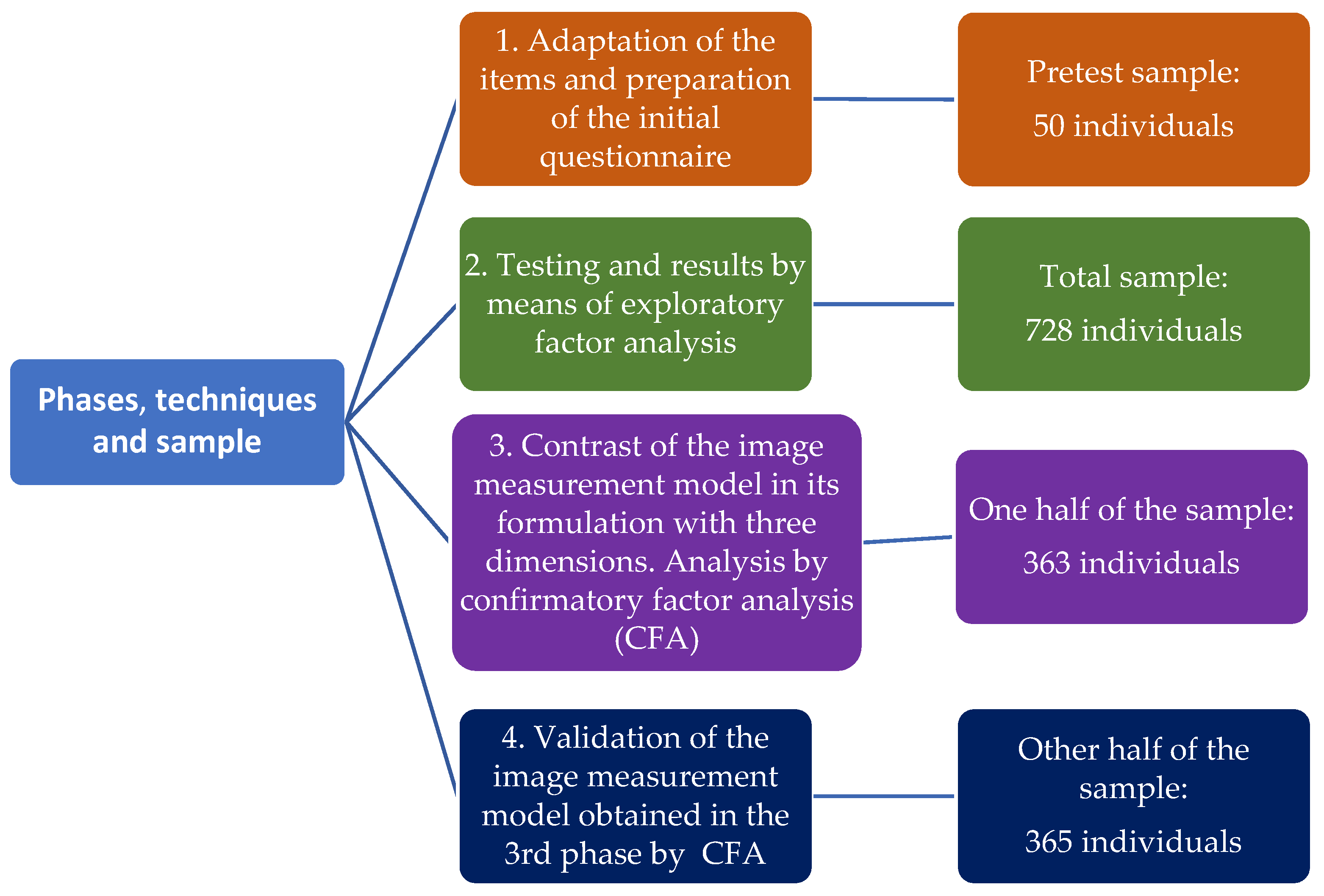

3.3. Data Collection and Analysis Procedure

4. Results

4.1. Phase 1. Pretest of the Questionnaire

4.2. Phase 2. Initial Validation through EFA

4.3. Division of the Sample

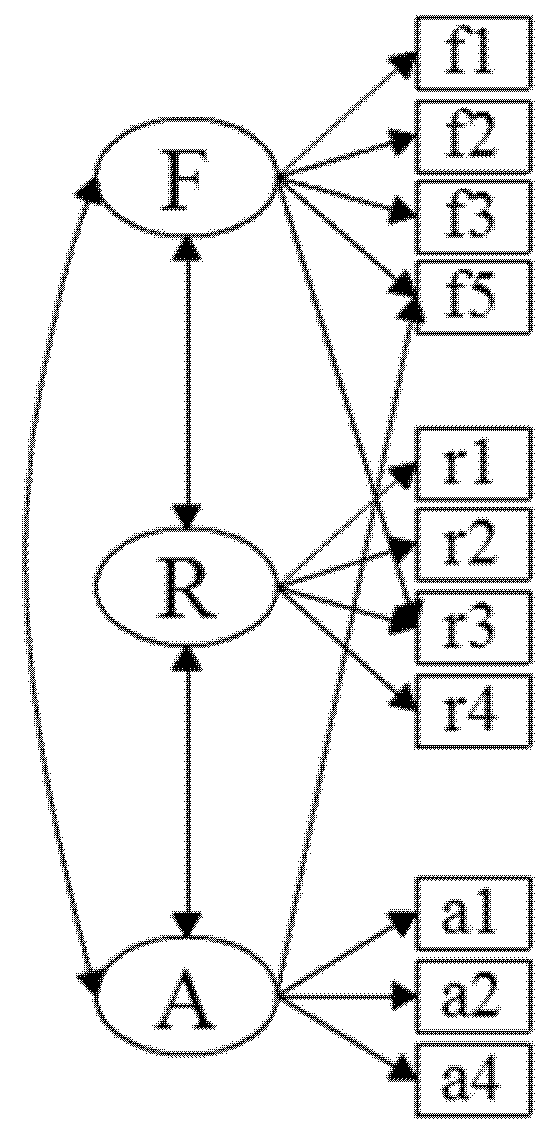

4.4. Phases 3 and 4. Estimation and Validation of the Model through CFA

4.5. Phase 3. Estimation of the Model

4.6. Phase 4. Validation of the Model

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

- the universality of the measurement scale proposed;

- its validation through other work in different sectors;

- considering reputation as a necessary factor in measuring image.

5.2. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, Y.; Green, A.; Pensiero, N. Expansion of Higher Education and Inequality of Opportunities: A Cross-National Analysis. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2016, 38, 242–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshtaria, T.; Datuashvili, D.; Matin, A. The Impact of Brand Equity Dimensions on University Reputation: An Empirical Study of Georgian Higher Education. J. Mark. High. Educ. 2020, 30, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhat, K.; Mokhtar, S.S.M.; Salleh, S.B.M. Role of Brand Experience and Brand Affect in Creating Brand Engagement: A Case of Higher Education Institutions (HEIs). J. Mark. High. Educ. 2021, 31, 107–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, M.; Yang, S.-U. Toward the Model of University Image: The Influence of Brand Personality, External Prestige, and Reputation. J. Public Relat. Res. 2008, 20, 357–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çetin, R. Planning and Implementing Institutional Image and Promoting Academic Programs in Higher Education. J. Mark. High. Educ. 2004, 13, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafuente Ruiz de Sabando, A.; Forcada Sainz, F.J.; Zorrilla Calvo, M.P. The University Image: A Model of Overall Image and Stakeholder Perspectives. Imagen Univ. Modelo Imagen Glob. Perspect. Grupos Interés 2018, 19, 63–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del-Castillo-Feito, C.; Blanco-González, A.; González-Vázquez, E. The Relationship between Image and Reputation in the Spanish Public University. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2019, 25, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, A.; Sulaiman, Z.; Qureshi, M.I. Student’s Perceived University Image Is an Antecedent of University Reputation. Int. J. Psychosoc. Rehabil. 2020, 24, 650–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.J.; Rasli, A.B.M.; Ibn-e-Hassan Rasli, A.B.M. University Branding: A Myth or a Reality. Pak. J. Commer. Soc. Sci. PJCSS 2012, 6, 168–184. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, N.; Leblanc, G. Corporate Image and Corporate Reputation in Customers’ Retention Decisions in Services. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2001, 8, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, C.; Moorhouse, J.; Dunnett, A.; Barry, C. University Choice: Which Attributes Matter When You Are Paying the Full Price? Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2015, 39, 670–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghaz, A.; Hashemi, A.; Sharifi Atashgah, M.S. Factors Contributing to University Image: The Postgraduate Students’ Points of View. J. Mark. High. Educ. 2015, 25, 104–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massoud, H.K.; Ayoubi, R.M. Do Flexible Admission Systems Affect Student Enrollment? Evidence from UK Universities. J. Mark. High. Educ. 2019, 29, 84–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, A.; Bosque, I.R. del. Identidad, imagen y reputación de la empresa: Integración de propuestas teóricas para una gestión exitosa. Cuad. Gest. 2014, 14, 97–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, B.; Zinkhan, G.M.; Jaju, A. Marketing Images: Construct Definition, Measurement Issues, and Theory Development. Mark. Theory 2001, 1, 201–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmer, J.M.T. Corporate Identity, Corporate Branding and Corporate Marketing—Seeing through the Fog. Eur. J. Mark. 2001, 35, 248–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curras Perez, R. Identidad e imagen corporativas: Revisión conceptual e interrelación. Teoría Praxis 2010, 7, 9–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.L.; James, J.D.; Kim, Y.K. A Reconceptualization of Brand Image. Int. J. Bus. Adm. 2014, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, I.; Olmedo, I. Revisión teórica de la reputación en el entorno empresarial. Cuad. Econ. Dir. Empresa 2010, 13, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kazoleas, D.; Kim, Y.; Anne Moffitt, M. Institutional Image: A Case Study. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2001, 6, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barich, H.; Kotler, P. A Framework for Marketing Image Management. MITSloan 1991, 32, 94–104. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, K.L. Conceptualizing, Measuring, and Managing Customer-Based Brand Equity. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervera, A.; Schlesinger, W.; Mesta, M.Á.; Sánchez, R. Medición de la imagen de la universidad y sus efectos sobre la identificación y lealtad del egresado: Una aproximación desde el modelo de beerli y díaz (2003). Rev. Esp. Investig. Mark. ESIC 2012, 16, 7–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, E.M.; Montaner, T.M.; Pina, J.M.P. Propuesta de una metodología. Medición de la imagen de marca. Un estudio explorativo. ESIC Mark. 2004, 35, 199–216. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, E.; Gutiérrez, T.M.; Pérez, J.M.P. Propuesta de medición de la imagen de marca: Un análisis aplicado a las extensiones de marca. RAE Rev. Astur. Econ. 2005, 33, 89–112. [Google Scholar]

- Matínez, E.M.; Montaner, T.M.; Pina, J.M.P. Estrategia de promoción e imagen de marca: Influencia del tipo de promoción, de la notoriedad de la marca y de la congruencia de beneficios. Rev. Esp. Investig. Mark. 2007, 11, 27–52. [Google Scholar]

- Buil, I.B.; Martínez, E.M.; Pina, J.M.P. Un modelo de evaluación de las extensiones de marca de productos y de servicios. Rev. Eur. Dir. Econ. Empresa 2008, 17, 167–186. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, B.B.; Levy, S.J. The Product and the Brand. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1955, 33, 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Martineau, P. Sharper Focus for the Corporate Image. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1958, 36, 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Arpan, L.M.; Raney, A.A.; Zivnuska, S. A Cognitive Approach to Understanding University Image. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2003, 8, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, S.H. Nurturing Corporate Images. Eur. J. Mark. 1977, 11, 119–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.J.; Barrett, J.D. Corporate Philanthropy, Criminal Activity, and Firm Reputation: Is There a Link? J. Bus. Ethics 2000, 26, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fombrun, C.J.; Gardberg, N.A.; Barnett, M.L. Opportunity Platforms and Safety Nets: Corporate Citizenship and Reputational Risk; SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 1088404; Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias, S.; Calvo, A.; López, V.A. Una aproximación empírica al concepto de reputación. In Gestión Científica Empresarial: Temas de Investigación Actuales; Netbiblo: La Coruña, Spain, 2003; pp. 87–104. ISBN 84-9745-051-5. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, B.; Gutierrez-Broncano, S.; Esteban, Á. Desarrollo de Un Concepto de Reputación Corporativa Adaptado a Las Necesidades de La Gestión Empresarial. Strategy Manag. Rev. 2012, 3, 9–31. [Google Scholar]

- Orozco-Toro, J.A.; Ferré-Pavia, C.C. Los índices de reputación corporativa y su aplicación en las empresas de comunicación. In Comunicació i Risc: III Congrés Internacional Associació Espanyola d’Investigació de la Comunicació; Universitat Rovira i Virgili: Tarragona, Spain, 2012; p. 42. ISBN 978-84-615-5678-6. [Google Scholar]

- Chun, R. Corporate Reputation: Meaning and Measurement. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2005, 7, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingenhoff, D.; Fuhrer, T. Positioning and Differentiation by Using Brand Personality Attributes: Do Mission and Vision Statements Contribute to Building a Unique Corporate Identity? Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2010, 15, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beerli Palacio, A.; Díaz Meneses, G.; Pérez Pérez, P.J. The Configuration of the University Image and Its Relationship with the Satisfaction of Students. J. Educ. Adm. 2002, 40, 486–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flavián, C.; Torres, E.; Guinalíu, M. Corporate Image Measurement: A Further Problem for the Tangibilization of Internet Banking Services. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2004, 22, 366–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, M. El Turismo Enológico Desde la Perspectiva de la Oferta; Editorial Universitaria Ramón Areces: Madrid, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, M.G.C.; Coelho, A.M. El impacto de la reputación en el desempeño de la organización en la perspectiva de los miembros de las cooperativas. ESIC Mark. 2015, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luque-Martínez, T.; Barrio-García, S. Modelling University Image: The Teaching Staff Viewpoint. Public Relat. Rev. 2009, 35, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azoury, N.; Daou, L.; Khoury, C.E. University Image and Its Relationship to Student Satisfaction- Case of the Middle Eastern Private Business Schools. Int. Strateg. Manag. Rev. 2014, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patlán, J.; Martínez, E. Evaluación de La Imagen Organizacional Universitaria En Una Institución de Educación Superior. Contad. Adm. 2017, 62, 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safón, V. Inter-Ranking Reputational Effects: An Analysis of the Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU) and the Times Higher Education World University Rankings (THE) Reputational Relationship. Scientometrics 2019, 121, 897–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luque-Martínez, T.; Faraoni, N.; Doña-Toledo, L. Meta-ranking de universidades. Posicionamiento de las universidades españolas. Rev. Esp. Doc. Científica 2018, 41, e198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. An Overview of Psychological Measurement. In Clinical Diagnosis of Mental Disorders: A Handbook; Wolman, B.B., Ed.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1978; pp. 97–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Balbin, B.J.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed.; Pearson Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River NJ, USA, 2006; ISBN 0130329290. [Google Scholar]

- Dancey, C.P.; Reidy, J. Statistics without Maths for Psychology; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2007; ISBN 0273726021. [Google Scholar]

- Lung-Yut-Fong, A.; Lévy-Leduc, C.; Cappé, O. Homogeneity and change-point detection tests for multivariate data using rank statistics. J. Société Fr. Stat. 2015, 156, 133–162. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle, R.H. 16—Confirmatory Factor Analysis. In Handbook of Applied Multivariate Statistics and Mathematical Modeling; Tinsley, H.E.A., Brown, S.D., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 465–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Items Proposed in Each of the Three Dimensions | Significance in Studies | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Martínez et al. (2004) [24] | Martínez et al. (2005) [25] | Martínez et al. (2007) [26] | Buil et al. (2008) [27] | |

| FUNCTIONAL IMAGE | ||||

| F1 The products are high quality. | Signif. | Signif. | Signif. | Signif. |

| F2 The products present characteristics that other brands do not have. | -------- | Signif. | Signif. | -------- |

| F3 The products have better characteristics than the competition. | -------- | -------- | -------- | Signif. |

| F4 Consuming this brand is very unlikely to cause problems or unforeseen events. | -------- | Not Signif. | -------- | -------- |

| F5 The competition’s products are usually cheaper. | -------- | Signif. | -------- | Not Signif. |

| F6 The models are cheap in relation to other brands. | Signif. | -------- | -------- | -------- |

| F7 I like the design of the models. | Signif. | -------- | -------- | -------- |

| AFFECTIVE IMAGE | ||||

| A1 It is a brand that arouses positive feelings. | -------- | Signif. | Signif. | Signif. |

| A2 This brand conveys a personality that differentiates it from rival brands. | -------- | Signif. | Signif. | Signif. |

| A3 Buying this brand says something about the class of person you are. | -------- | Not Signif. | -------- | -------- |

| A4 I have an image of the type of people that buy this brand. | Signif. | Not Signif. | -------- | -------- |

| A5 It is a brand that does not disappoint its customers. | -------- | Signif. | Signif. | Signif. |

| A6 The brand conveys values that differentiate it from other brands in the sector. | Signif. | -------- | -------- | -------- |

| A7 The brand strives to innovate in new models, services and/or technology. | Signif. | -------- | -------- | -------- |

| REPUTATION | ||||

| R1 It is one of the best brands in the sector. | -------- | Signif. | Signif. | Signif. |

| R2 It is a brand that is committed to society. | -------- | |||

| R3 It is a much consolidated brand in the market. | -------- | Signif. | -------- | -------- |

| R4 The brand is highly regarded. | Signif. | |||

| R5 The brand is a professional in its category. | Signif. | Signif. | Signif. | Signif. |

| R6 You can trust this brand. | Signif. | |||

| Functional Image (F) | Affective Image (A) | Reputation (R) |

|---|---|---|

| f1. Education and training in the private university are of high quality. | a1. The private university arouses positive sentiments. | r1. The private university is the best option. |

| f2. The private university’s premises are of high quality. | a2. The private university conveys a personality that differentiates it from the state university. | r2. The private university is committed to society. |

| f3. The research produced in a private universities is of high quality. | a3. Enrolling in a private university says something about the class of person you are. | r3. The private university is much consolidated in the market. |

| f4. Private universities present characteristics that state ones do not have. | a4. The private university does not disappoint its customers. | r4. The private university occupies very high positions in university rankings. |

| f5. The private university gives high value in relation to the price that must be paid for it. | a5. The private university has a differentiated ideological component. |

| Phase 3 | Phase 4 | |

|---|---|---|

| CFI | 0.965 | 0.963 |

| NNFI | 0.950 | 0.947 |

| NFI | 0.952 | 0.951 |

| RMSEA | 0.086 | 0.088 |

| Factor | Variable | Phase 3 | Phase 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| F | f1 | 0.865 ** | 0.883 ** |

| f2 | 0.776 ** | 0.777 ** | |

| f3 | 0.816 ** | 0.838 ** | |

| f5 | 0.286 ** | 0.479 ** | |

| r3 | 0.176 ** | 0.358 ** | |

| R | r1 | 0.852 ** | 0.854 ** |

| r2 | 0.892 ** | 0.903 ** | |

| r3 | 0.835 ** | 0.827 ** | |

| r4 | 0.754 ** | 0.537 ** | |

| A | f5 | 0.53 ** | 0.341 ** |

| a1 | 0.82 ** | 0.785 ** | |

| a2 | 0.755 ** | 0.769 ** | |

| a4 | 0.772 ** | 0.732 ** | |

| Cov(F,R) | 0.631 | 0.708 | |

| Cov(F,A) | 0.766 | 0.822 | |

| Cov(R,A) | 0.901 | 0.926 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gutiérrez-Villar, B.; Alcaide-Pulido, P.; Carbonero-Ruz, M. Measuring a University’s Image: Is Reputation an Influential Factor? Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12010019

Gutiérrez-Villar B, Alcaide-Pulido P, Carbonero-Ruz M. Measuring a University’s Image: Is Reputation an Influential Factor? Education Sciences. 2022; 12(1):19. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12010019

Chicago/Turabian StyleGutiérrez-Villar, Belén, Purificación Alcaide-Pulido, and Mariano Carbonero-Ruz. 2022. "Measuring a University’s Image: Is Reputation an Influential Factor?" Education Sciences 12, no. 1: 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12010019

APA StyleGutiérrez-Villar, B., Alcaide-Pulido, P., & Carbonero-Ruz, M. (2022). Measuring a University’s Image: Is Reputation an Influential Factor? Education Sciences, 12(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12010019