Fashion Design Education and Sustainability: Towards an Equilibrium between Craftsmanship and Artistic and Business Skills?

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Complex Challenges of Sustainability in the Fashion Sector

1.2. The New Roles of Fashion Designers

1.3. The Need for Change in Fashion Design Education

2. The Importance of Sustainability in Fashion Education: Literature Review

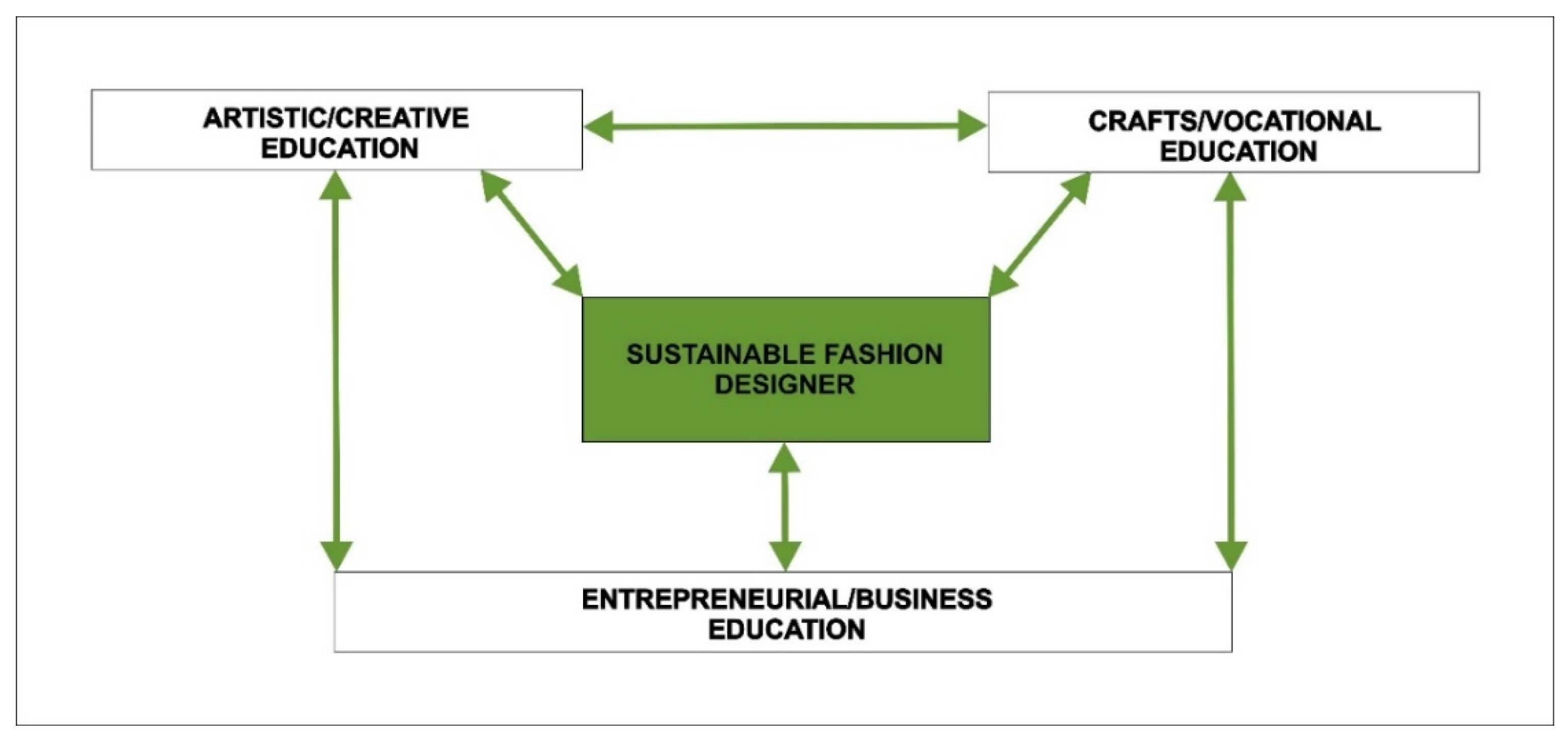

2.1. Fashion Designers as Artists, Craftspeople, and Entrepreneurs or Employees in the Fashion Industry

2.2. Value-Based Learning

2.3. The Inclusion of Sustainability-Related Themes in Fashion Design Education

2.4. Limitations and Challenges of Sustainable Fashion Education

Design educators should be guardians of possibility and guardians of the possibility of possibility (…) Too often design, including fashion design, is reduced to the creation of new products within the existing world, which we are expected to accept as is (…) Absolutely, we must learn from the past, but we must always move forward (…).

A large majority of design and applied art institutions, in fact, focus on the old concept of product-centred education, feeding an enduring demand in prospective students, who are usually fascinated by fashion for its media and social impact, driven by individualism and not pragmatically informed by the professional context of designing and developing real products in a dramatically changing world.

3. Research Design and Methodology

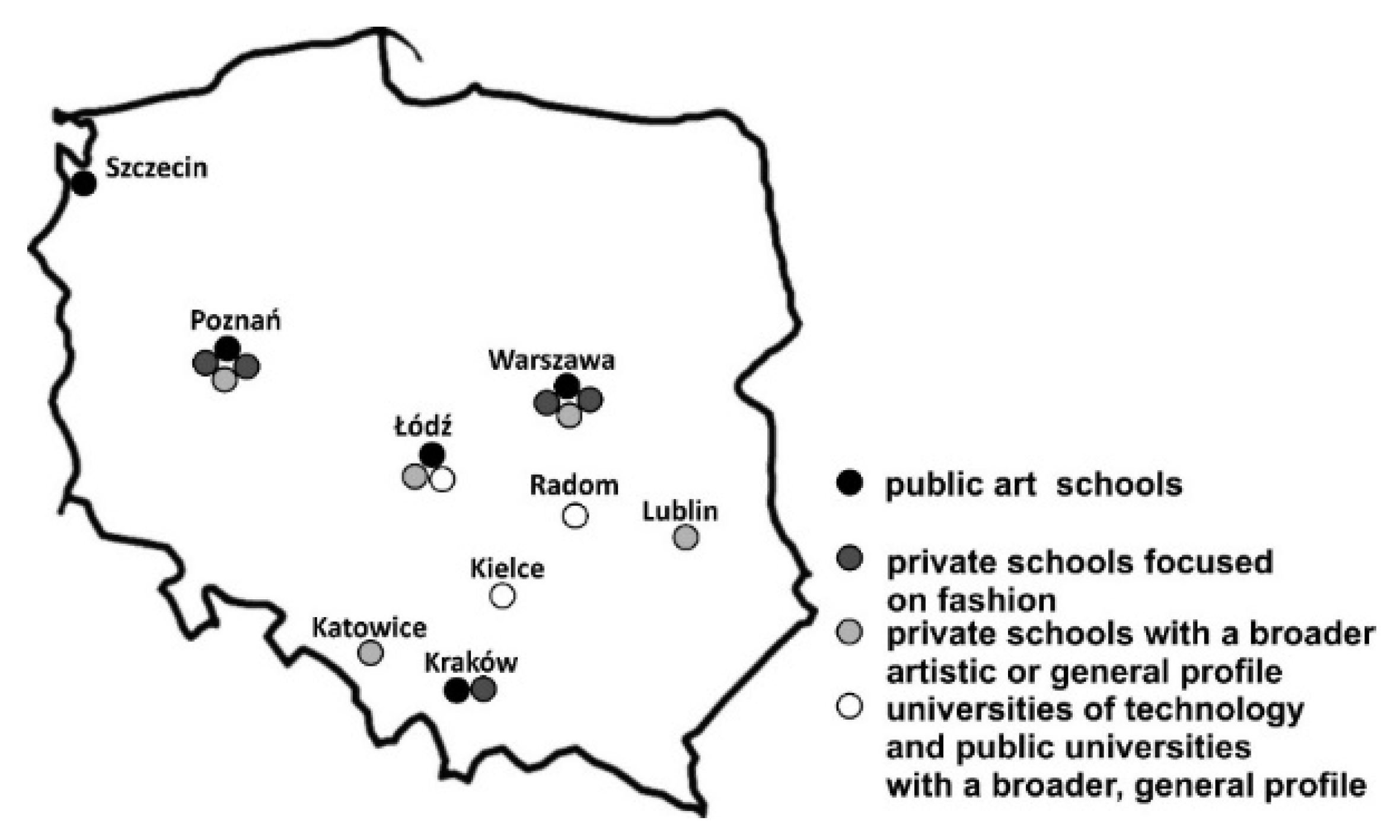

3.1. Identification of Post-Secondary Schools Offering Fashion Majors in Poland

3.2. Interviews

3.3. Main Themes and Dimensions of the Analysis

4. Results: Sustainability in the Education of Future Fashion Designers in Poland

4.1. Sustainability Education as a Part of the Artistic Dimension of Fashion Education

4.1.1. Creative Reuse of Textiles and Other Materials

4.1.2. Socially Engaged Fashion

4.1.3. Rethinking the Philosophy of Fashion, Preparing Statements and Manifestos on Sustainable Fashion

4.1.4. Cultural Heritage as Fashion Inspiration

4.1.5. Sustainability as a Leitmotif of Diploma Collections

4.2. Educating for Sustainability as Part of the Craft and Practical Skills Dimension of Fashion Education

4.2.1. Making Fashion Students Aware of Practical Sustainability Challenges and Possible Solutions

4.2.2. Sustainable Selection and Use of Textiles, Minimising Textile Waste

4.2.3. Enhancing the Quality of Garment and Apparel Craftsmanship

4.2.4. Awareness of Ethical Challenges Involved in Fashion Production

4.2.5. Awareness of Special Needs of Particular Social and Age Groups

4.2.6. Making Use of Local Heritage and Production Traditions

4.2.7. Designers’ Potential to Impact Consumer Awareness and Choices

4.3. Educating for Sustainability as an Element of Business and Entrepreneurship Education

4.3.1. CSR in Fashion

4.3.2. Creating and Managing Sustainable Fashion Brands

- Elaborating the development strategy of a fashion brand; developing marketing communication for the brand and its values, ideas, products, and their features (how to arouse customers’ interest by selling them not only products but also the ideas behind them) and deciding on the desired target group—discerning their needs, devising ways of reaching them, and developing the skills and action needed to establish relations with potential clients (e.g., VIAMODA offered a series of lectures on marketing communication in fashion, with themes such as ‘Responsible fashion and responsibly on fashion—how to create communication content for fashion products in line with the sustainable fashion paradigm?’ [55];

- CSAFD published an article in its journal, Tuba, on the importance of marketing communication and the most efficient allocation of spending on it, stressing the need to inform potential customers about the product rather than, for example, investing a lot of money and effort in costly shows, and the necessity of planned communication with foreseeable timing in order to stay in regular touch with potential buyers and customers, as well as a predictable, repeated rhythm of release of new collections [56].

- It was similarly stressed that designers’ responsibility for their own products and brands—also in terms of marketing communication—should always be implemented with empathy and respect for their clients and their situation (e.g., as a semester task at one of the interviewed schools, students were asked to analyse a recent advertising campaign by the Polish brand Medicine, which during the pandemic decided to run a controversial campaign with the motto ‘Clothes can cure you’ and was severely criticised, even by fast fashion consumers, for what was perceived as insensitive and irresponsible communication; I2). Sending misleading marketing communications is another problem (e.g., brands that sell garments made from natural fabrics and promote themselves as ‘fully’ responsible, even though their products are made from conventional cotton or natural silk). Schools’ task is not only to make their students aware that such marketing signals are misleading but also to highlight their detrimental impact on consumers’ awareness of real sustainability issues (I2).

- Creation of CSR strategies and ways of communicating them to co-operators and clients (e.g., MSKPU’s emphasis on implementing a holistic CSR approach to design is evident in an original textbook on ethics in fashion published in Polish by the school’s director, Magdalena Płonka [57]; the school and its staff also participated in events on CSR and sustainability-related issues such as the Business Fashion Environment Summit in Warsaw in 2020). It was stressed that developing brands founded on values, in particular in the context of reoccurring crisis situations in the market, makes it easier for such brands to better cope with challenges arising in difficult economic times (I2).

- Giving students skills and ‘tools’—helping them to develop competencies to cooperate effectively within the organisational framework of a large fashion firm (e.g., cooperation with purchasing, marketing, or public relations (PR) departments).

- Making students aware that sometimes economic efficiency measures may be very much in line with sustainable fashion desiderata (for instance, designing clothes from fabric scraps or recycled textiles, minimising fabric waste) (I1, I2, I3).

5. Conclusions

5.1. The Presence of Sustainable Fashion-Related Themes in the Activities of Fashion Schools in Poland

5.2. Challenges in Sustainable Education of Fashion Designers in Poland

5.2.1. Lasting Impact on Attitudes and Practices

5.2.2. The Need for a Holistic Approach

5.2.3. Awareness and Attitudes of the General Public

5.2.4. Institutional Context and Possibilities for Cooperation with External Partners

5.2.5. Availability of Educational Materials

5.2.6. Availability of Sustainable Fabrics and Other Supplies

6. Perspectives and Closing Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gwilt, A.; Rissanen, T. (Eds.) Shaping Sustainable Fashion. Changing the Way We Make and Use Clothes; Earthscan: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, K. Sustainable Fashion and Textiles. Design Journeys; Earthscan, Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Niinimäki, K. Sustainable Fashion in a Circular Economy. In Sustainable Fashion in a Circular Economy; Niinimäki, K., Ed.; Aalto University School of Arts, Design and Architecture: Espoo, Finland, 2018; pp. 12–41. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/301138773.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- Thomas, S. Fashion Ethics; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, K.; Grose, L. Fashion and Sustainability: Design for Change; Laurence King: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gwilt, A. A Practical Guide to Sustainable Fashion; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Henninger, C.E.; Alevizou, P.J.; Goworek, H.; Ryding, D. (Eds.) Sustainability in Fashion. A Cradle to Upcycle Approach; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Roos, S.; Sandin, G.; Zamani, B.; Peters, G.; Svanström, M. Will clothing be sustainable? Clarifying sustainable fashion. In Textiles and Clothing Sustainability. Implications in Textiles and Fashion; Muthu, S.S., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- D’Adamo, I.; Lupi, G. Sustainability and Resilience after COVID-19: A Circular Premium in the Fashion Industry. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, G.; Li, M.; Lenzen, M. The need to decelerate fast fashion in a hot climate—A global sustainability perspective on the garment industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 295, 126390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grose, L. Fashion design education for sustainability practice. Reflections on undergraduate level teaching. In Sustainability in Fashion and Textiles. Values, Design, Production and Consumption; Gardetti, M.A., Torres, A.L., Eds.; Routledge/Green Leaf Publishing: London, UK, 2013; pp. 134–147. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, K. Design for sustainability in fashion and textiles. In The Handbook of Fashion Studies; Black, S., de la Haye, A., Entwistle, J., Rocamora, A., Root, R.A., Thomas, H., Eds.; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2013; pp. 557–574. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D. Fashion design. In The Routledge Handbook of Sustainability and Fashion; Fletcher, K., Tham, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 234–242. [Google Scholar]

- Fuad-Luke, A. ‘Slow Design’: A paradigm Shift in Design Philosophy? In Proceedings of the Design by Development (dyd02) 2nd International Conference on Open Collaborative Design for Sustainable Innovation, Bangalore, India, 1–2 December 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ræbild, U. From Fashion Pusher to Garment Usher? How Fashion Design Students at Design School Kolding Currently Explore their Future Role in Society. In Soft Landing: Cumulus Think Tank Publication No. 3; Nimkurlat, N., Raebild, U., Piper, A., Eds.; Aalto University, School of Arts, Design and Architecture: Helsinki, Finland, 2018; pp. 113–126. Available online: https://www.cumulusassociation.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/PDF_SINGLE_cumulus_soft_landing.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- Earley, R. The New Designers: Working Towards Our Eco Fashion Future. In Proceedings of the Dressing Rooms: Current Perspectives on Fashion and Textiles Conference, Oslo, Norway, 14–16 May 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, G.; Simoes, I. Fashion Design and Entrepreneurship: A Strategic Model for Higher Education in Portugal. In Proceedings of the Virtuous Circle, Summer Cumulus Conference, Milan, Italy, 3–7 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Faerm, S. Building best practices for fashion design pedagogy: Meaning, preparation, and impact the increasingly volatile professional world for which students must be trained. Cuaderno 2015, 53, 189–213. [Google Scholar]

- Cleverdon, L.; Pole, S.; Weston, R.; Banga, S.; Tudor, T. The Engagement of Students in Higher Education Institutions with the Concepts of Sustainability: A Case Study of the University of Northampton, in England. Resources 2017, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Designing for a circular economy: Lessons from the great recovery 2012–2016; Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufacturers and Commerce: London, UK, 2016; Available online: https://www.thersa.org/globalassets/pdfs/reports/the-great-recovery---designing-for-a-circular-economy.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2021).

- Onur, D.A. Integrating Circular Economy, Collaboration and Craft Practice in Fashion Design Education in Developing Countries: A Case from Turkey. Fash. Pract. 2020, 12, 55–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leerberg, M.; Riisberg, V.; Boutrup, J. Design Responsibility and Sustainable Design as Reflective Practice: An Educational Challenge. Sust. Dev. 2020, 18, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, K.; Williams, D. Fashion education in sustainability in practice. RJTA 2013, 17, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertola, P. Reshaping Fashion Education for the 21st Century World. In Soft Landing: Cumulus Think Tank Publication No. 3; Nimkurlat, N., Raebild, U., Piper, A., Eds.; Aalto University, School of Arts, Design and Architecture: Helsinki, Finland, 2018; pp. 7–15. Available online: https://www.cumulusassociation.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/PDF_SINGLE_cumulus_soft_landing.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- Salolainen, M.; Leppisaari, A.-M.; Niinimäki, K. Transforming Fashion Expression through Textile Thinking. Arts 2019, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, V. Future of Fashion Education in India—Focus and Emerging Scenarios. In Soft Landing: Cumulus Think Tank Publication No. 3; Nimkurlat, N., Raebild, U., Piper, A., Eds.; Aalto University, School of Arts, Design and Architecture: Helsinki, Finland, 2018; pp. 17–23. Available online: https://www.cumulusassociation.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/PDF_SINGLE_cumulus_soft_landing.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- Finn, A.L.; Fraser, K. The Big Picture: An Integrated Approach to Fashion Design Education. In Proceedings of the Fashion Industry New Zealand (FINZ) Annual Education Conference: The Broader Perspective of Design, Wellington, New Zealand, 8–10 August 2007. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Raciniewska, A. When ethical fashion is a challenge: Polish case. In Fashion and Its Multi-Cultural Facets; Hunt-Hurst, P., Ramsamy-Iranah, S., Eds.; Interdisciplinary Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 139–148. [Google Scholar]

- Koszewska, M.; Rahman, O.; Dyczewski, B. Cricular fashion—Consumers’ attitudes in cross-national study: Poland and Canada. AUTEX Res. J. 2020, 20, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reif, R.; Zalewska, K.; Suchecki, K.; Kin, K. Czy Ekologia jest w Modzie. Raport o Odpowiedzialnej Konsumpcji i Zrównoważonej Modzie w Polsce; Accenture: Warszawa, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- D’Itria, E. Fashion design education and sustainability. A challenge accepted. In Proceedings of the 3rd LeNS World Distributed Conference: Designing Sustainability for All; Ambrosio, M., Vezzoli, C., Eds.; Edizioni POLI.design: Milano, Italy, 2019; Volume 4, pp. 1303–1308. [Google Scholar]

- Black, S. Editorial. Fash. Pract. 2009, 1, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Payne, A.; Ibanez, I.; Pearson, L. New Materiality: “Making Do” and Making Connections. In Soft Landing: Cumulus Think Tank Publication No. 3; Nimkurlat, N., Raebild, U., Piper, A., Eds.; Aalto University, School of Arts, Design and Architecture: Helsinki, Finland, 2018; pp. 35–50. Available online: https://www.cumulusassociation.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/PDF_SINGLE_cumulus_soft_landing.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- Rissanen, T. Fashion design education as leadership development. In Proceedings of the Global Fashion Conference 2018, London, UK, 31 October–1 November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Acevedo-Duque, Á.; Gonzalez-Diaz, R.; Vargas, E.C.; Paz-Marcano, A.; Muller-Pérez, S.; Salazar-Sepúlveda, G.; Caruso, G.; D’Adamo, I. Resilience, Leadership and Female Entrepreneurship within the Context of SMEs: Evidence from Latin America. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obregon, C. Sustainable Fashion Education: From Trend to Paradigm? Master’s Thesis, The Department of Fashion and Clothing Desig, Aalto University School of Arts, Design & Architecture, Helsinki, Finland, 2012. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/80705234.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- Nimkurlat, N.; Raebild, U.; Piper, A. Introduction. In Soft Landing: Cumulus Think Tank Publication No. 3; Nimkurlat, N., Raebild, U., Piper, A., Eds.; Aalto University, School of Arts, Design and Architecture: Helsinki, Finland, 2018; pp. 1–4. Available online: https://www.cumulusassociation.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/PDF_SINGLE_cumulus_soft_landing.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- Smal, D.; Harvey, N. The Wheel: A Teaching Tool for Fashion Design Students. In Proceedings of the Global Fashion Conference 2018, London, UK, 31 October–1 November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara, M. Smart Experience in Fashion Design: A Speculative Analysis of Smart Material Systems Applications. Arts 2019, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gam, H.J.; Banning, J. Teaching Sustainability in Fashion Design Courses through a Zero-Waste Design Project Clothing and Textiles. Res. J. 2020, 38, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wubs, B.; Lavanga, M.; Darpy, D.; Depeyre, C.; Segreto, L.; Popowska, M. RE-FRAME FASHION Report. Innovation in Fashion Education; Erasmus University Rotterdam: Rotterdam, The Netherlands; Université Paris-Dauphine: Paris, France; Gdańsk University of Technology: Gdańsk, Poland, 2020; REFRAME FASHION Publications, Erasmus+ Strategic Partnerships for Higher Education Programme of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Bill, A. “Blood, Sweat and Shears”: Happiness, Creativity, and Fashion Education. Fash. Theory 2012, 16, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rissanen, T. The fashion system through a lens of zerowaste fashion design. In The Routledge Handbook of Sustainability and Fashion; Fletcher, K., Tham, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 201–209. [Google Scholar]

- Tham, M. Futures of futures studies in fashion. In The Routledge Handbook of Sustainability and Fashion; Fletcher, K., Tham, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 283–292. [Google Scholar]

- Rissanen, T. Possibility in Fashion Design Education: A Manifesto. Utop. Stud. 2018, 28, 528–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustyn, M. Crossroads—O relacjach mody z innymi dziedzinami. Tuba 2020, 15, 12–13. [Google Scholar]

- The Student Group of Sculpture at the UAP in Poznań. Available online: https://uap.edu.pl/uczelnia/wydzialy/wydzial-rzezby/kolo-naukowe-rzezby/ (accessed on 31 March 2021).

- The Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/385915461962/posts/10157276932071963/ (accessed on 13 March 2021).

- Trendstudio. Available online: https://trendstudio.pl/ (accessed on 10 April 2021).

- Pereira, L.; Carvalho, R.; Dias, Á.; Costa, R.; António, N. How Does Sustainability Affect Consumer Choices in the Fashion Industry? Resources 2021, 10, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siałkowski, K. Wyjątkowy pokaz mody w Warszawie. “Futra noszą piękne zwierzęta i bardzo brzydcy ludzie”. Gazeta 2019. Available online: https://warszawa.wyborcza.pl/warszawa/7,54420,25416190,wyjatkowy-pokaz-mody-w-warszawie-futra-nosza-piekne-zwierzeta.html (accessed on 16 April 2021).

- Viva! Foundation. Available online: https://viva.org.pl/ (accessed on 16 April 2021).

- Rosińska, M. Przemyśleć u/życie. Projektanci. Przedmioty. Życie Społeczne; Bęc Zmiana: Warszawa, Poland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- The Statute of VIAMODA. Available online: https://www.viamoda.edu.pl/o-uczelni/akty-prawne_s_60.html (accessed on 4 May 2021).

- Information on Lectures on the VIAMODA. Available online: https://www.viamoda.edu.pl/ (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Harel. Znajdź różnice-ostatnia dekada w polskiej modzie. Tuba 2016, 11, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Płonka, M. Etyka w Modzie—CSR w Przemyśle Odzieżowym; Em pe Studio Design: Warszawa, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Larmuth, M. Artisan. Tuba 2018, 12, 47. [Google Scholar]

- Klekot, E. The Seventh Life of Polish Folk Art and Craft. Etnološka Trib. 2010, 33, 71–85. [Google Scholar]

- MSKPU. Available online: https://mskpu.pl/2020/02/08/edukujemy-w-zakresie-srodowiska-naturalnego-oraz-dziko-zyjacych-zwierzat/ (accessed on 8 June 2021).

- LUT. Available online: https://www.zu.p.lodz.pl/eko-czy-ego (accessed on 8 June 2021).

- Natalia Penar Fashion Stylist. Available online: https://nataliapenar.com/fashioninfluencer/ (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- HTS in Katowice. Available online: http://www.wst.com.pl/news/biennale_internationale_design_saint_tienne-15_03_19/699 (accessed on 17 June 2021).

- The Strzemiński Academy of Art Lodz. Available online: https://www.asp.lodz.pl/index.php/pl/o-akademii/wystawy/12-inne-wystawy/1629-future-man-2052 (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- Modopolis-Forum of Polish Fashion. Available online: http://modopolis.pl/jak-dobrze-zyc-z-wujkiem-google-warsztat-online/ (accessed on 11 June 2021).

| Main Theme | Specific Sustainability-Related Themes | Frequency of the Appearance of a Given Theme on Social Media and on the Web Pages of Schools (5—Very Frequent, 1—Very Rare) |

|---|---|---|

| Fabrics and textiles as creative inspiration and as a challenge in terms of sustainable use | Deconstruction | 5 |

| Recycling and upcycling | 5 | |

| Ecological textiles and technological solutions (e.g., new fabrics, production processes, and dyeing) | 4 | |

| Appreciation for and potential use of local heritage, including textile and clothing production traditions | Using local heritage as a design inspiration (etnodizajn in Polish) [59] | 4 |

| Locally sourced fabrics and local production | 3 | |

| Traditional fabrics and fashion accessories; traditional, environmentally friendly production processes (e.g., using only organic ingredients and supplies) | 2 | |

| Shaping designers’ awareness of and sensitivity to current global problems | General sensitivity to global problems | 4 |

| Important problems and negative environmental and social impacts of the fashion industry, CSR, and ethics in fashion (people and animals) | 3 | |

| Empathy for and design tailored to the needs of specific societal and age groups (e.g., the elderly, the disabled, and refugees) | 1 | |

| Designers as sustainability activists | Broader sustainability issues as a design inspiration: ‘verbalisation’ of global and local ecological, social, economic, cultural, and spiritual issues through fashion (e.g., its form, materials used, slogans on clothing, etc.) | 2 |

| Designers’ role in educating the general public and shaping consumption patterns and consumer attitudes | 3 | |

| Designers as informed participants in the fashion market (entrepreneurs, employees, employers, and creators of comprehensive concepts of fashion brands) | Challenges of developing and managing sustainable fashion businesses and brands | 2 |

| Activity Type (Dimension of Analysis) | Percentage of Schools That Inform the General Public of Engagement in a Given Type of Activity |

|---|---|

| Inclusion of sustainability in official statements or other public communications (articles, blogs, podcasts, and manifestos) | 22 |

| Sustainability as a visible and promoted leitmotif throughout the curriculum (present in the majority of courses or as a separate course) | 22 |

| Sustainability activities and events organised by the school, compulsory for students | 22 |

| Activities and events organised by the school (e.g., conferences, workshops, and professional meetings) as an additional/extracurricular (educational) offer aimed at students or students and other (external) fashion professionals | 28 |

| Publishing on sustainable fashion | 28 |

| Participation of the school (lecturers and students) in sustainable fashion events and initiatives organised by other institutions and organisations in Poland and abroad | 50 |

| Promoting sustainable fashion events and initiatives organised by other (external) bodies | 50 |

| Inclusion of sustainability in student designs (created as assignments for particular courses or as the theme of end-of-year or graduation collections) | 56 |

| Events organised by schools (e.g., workshops) for the general public (non-specialist participants not connected with the fashion market) | 61 |

| Cooperation with other stakeholders on sustainable fashion initiatives (other schools, firms in the fashion industry, museums, and non-governmental organisations) | 61 |

| School Type | Average Number of Sustainable Fashion Activity Types a Given School Type Is Involved in (out of 10 Identified by the Authors) |

|---|---|

| Specialist private fashion schools | 8 |

| Public art schools | 4 |

| Private schools with a broader artistic or general profile | 2 |

| Public universities with a broader profile | 2 |

| Average for all schools offering fashion majors | 4 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Murzyn-Kupisz, M.; Hołuj, D. Fashion Design Education and Sustainability: Towards an Equilibrium between Craftsmanship and Artistic and Business Skills? Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 531. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11090531

Murzyn-Kupisz M, Hołuj D. Fashion Design Education and Sustainability: Towards an Equilibrium between Craftsmanship and Artistic and Business Skills? Education Sciences. 2021; 11(9):531. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11090531

Chicago/Turabian StyleMurzyn-Kupisz, Monika, and Dominika Hołuj. 2021. "Fashion Design Education and Sustainability: Towards an Equilibrium between Craftsmanship and Artistic and Business Skills?" Education Sciences 11, no. 9: 531. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11090531

APA StyleMurzyn-Kupisz, M., & Hołuj, D. (2021). Fashion Design Education and Sustainability: Towards an Equilibrium between Craftsmanship and Artistic and Business Skills? Education Sciences, 11(9), 531. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11090531