Children’s Right to Belong?—The Psychosocial Impact of Pedagogy and Peer Interaction on Minority Ethnic Children’s Negotiation of Academic and Social Identities in School

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. UNCRC, Minority Ethnic Children’s Rights, and the Spaces to Belong in School

“States Parties undertake to respect the right of the child to preserve his or her identity, including nationality, name and family relations as recognized by law without unlawful interference” and “where a child is illegally deprived of some or all of the elements of his or her identity, States Parties shall provide appropriate assistance and protection, with a view to re-establishing speedily his or her identity”.

1.2. Minority Ethnic Children, Cultural Identities, and Belonging in School

1.3. Schools as Sites of Mis/Recognition—Pedagogy and the Psychosocial

1.3.1. Pedagogic Divisiveness

“By converting social hierarchies into academic hierarchies, the educational system fulfils a function of legitimation which is more and more necessary to the perpetuation of the ‘social order’ as the evolution of the power relationship between classes tends more completely to exclude the imposition of a hierarchy based upon the crude and ruthless affirmation of the power relationship (p. 84)”.

1.3.2. The Emotionality of Learning and the Psychosocial

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Polish Ethnographic Study

2.1.1. Polish Ethnographic Study Sample

Mainstream Schooling Context—Kasia and Marcin

Heritage Language Enriched Context—Janek and Wiktoria

2.1.2. Methodology

Children’s Narratives

2.1.3. Discourse Analysis

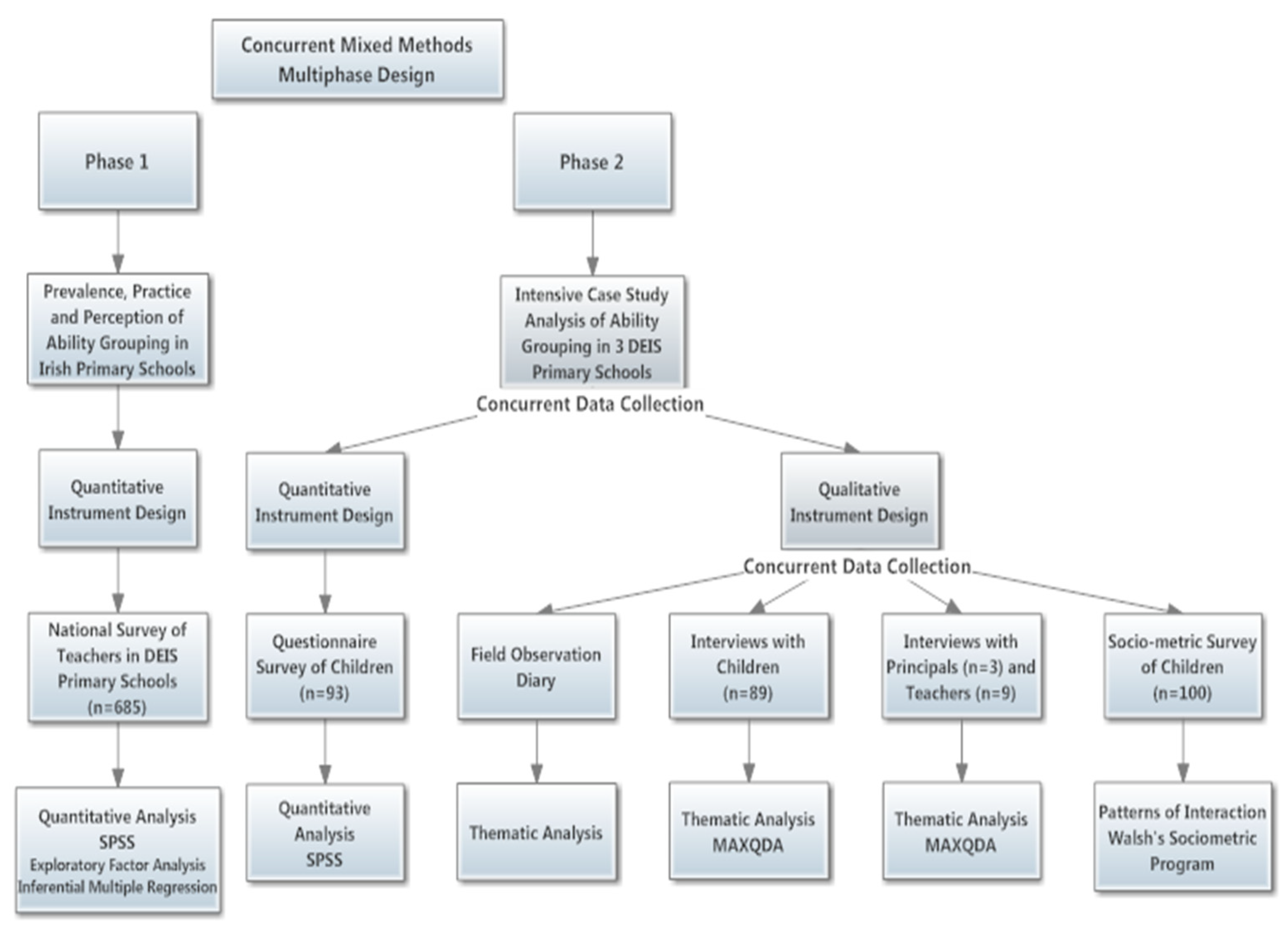

2.2. The Ability Grouping Study

2.2.1. National Survey of Teachers

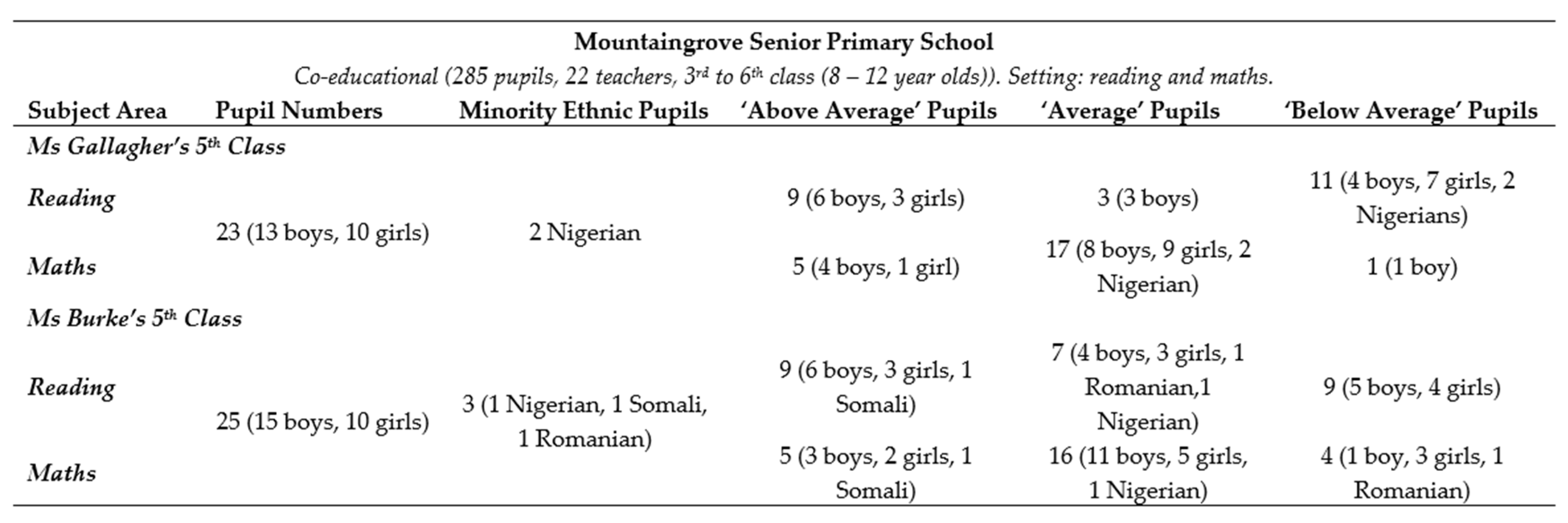

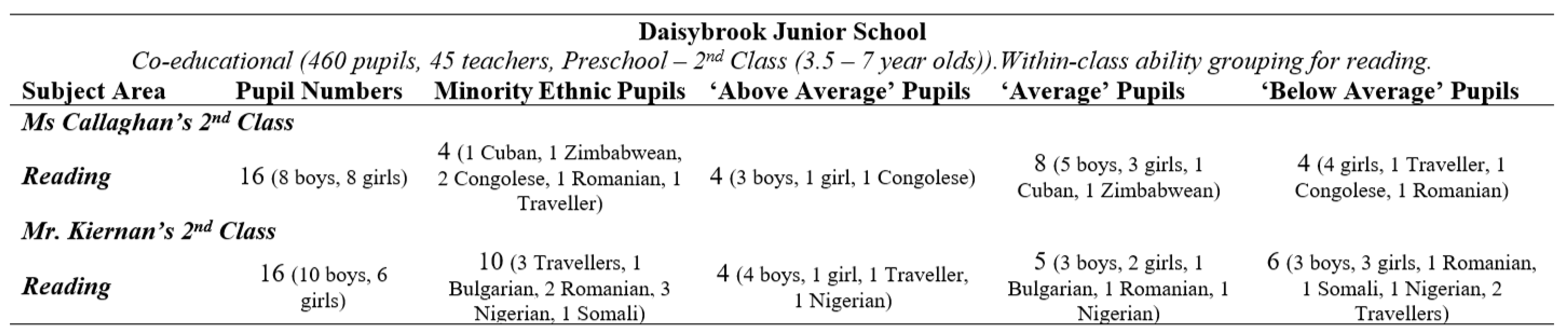

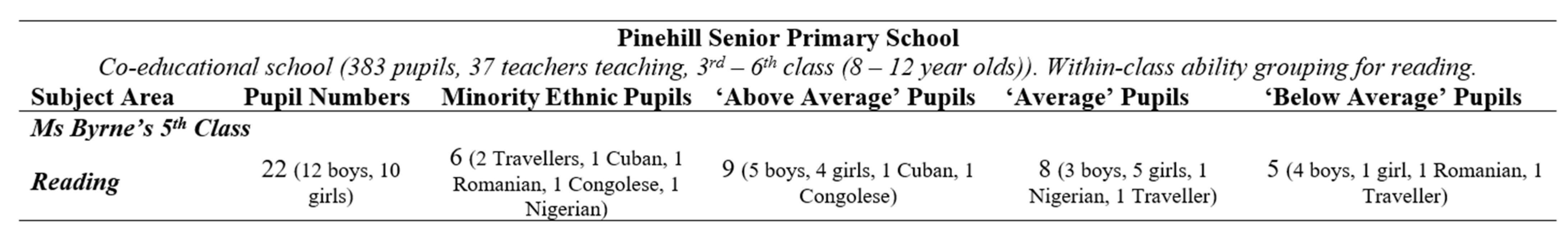

2.2.2. The Case Studies

2.2.3. The Ability Grouping Study Sample

National Survey Sample

Case Study Sample

2.2.4. Analysis

- Pedagogy and peers—Meaning making and re/negotiating identities in school, and

- The psychosocial impact of working to belong.

3. Results

3.1. Pedagogy and Peers—Meaning Making and Re/Negotiating Identities in School

“When you say you are Polish they just treat you differently, they talk to you less and they talk slowly so as you could understand” and she did not want to be treated that way, “I do not need this!” (Wiktoria)

“It’s funny as well that like in the second year groups those people arriving…those people who are from Eastern Europe the first year very much group together even though they are not from the same country […] while Kasia would very much not at all—and she would be the opposite also.”

3.2. The Psychosocial Impact of Working to Belong

“…that would probably make you feel ashamed that you are not in the higher group and especially if you were in the special group you would be ‘why am I not in there? I know how to read!’” (Robbie-M/A-Pinehill).

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IOM. International Migration Law N°34—Glossary on Migration; IOM: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rendall, M.; Salt, J. The foreign-born population. In Focus on People and Migration; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2005; pp. 131–151. Available online: https://data.oecd.org/migration/foreign-born-population.htm (accessed on 30 May 2021).

- OECD. International Migration Outlook 2020; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/migration/international-migration-outlook-1999124x.htm (accessed on 30 May 2021).

- Kitching, K. Childhood, Religion and School Injustice; Cork University Press: Cork, Ireland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Faas, D.; Foster, N.; Smith, A. Accommodating religious diversity in denominational and multi-belief settings: A cross-sectoral study of the role of ethos and leadership in Irish primary schools. Educ. Rev. 2020, 72, 601–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machowska-Kosciak, M. The Multilingual Adolescent Experience: Small Stories of Integration and Socialization by Polish Families in Ireland; Multilingual Matters: Clevedon, UK, 2020; Available online: https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.21832/9781788927680/html (accessed on 30 May 2021).

- McGillicuddy, D.; Devine, D. ‘You feel ashamed that you are not in the higher group’—Children’s psychosocial response to ability grouping in primary school. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2020, 46, 553–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, L. Reports of Racism in Ireland; INAR: Dublin, Ireland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Devine, D.; McGillicuddy, D. Positioning pedagogy-a matter of children’s rights. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 2016, 42, 424–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lundy, L. A Lexicon for Research on International Children’s Rights in Troubled Times. Int. J. Child. Rights 2019, 27, 595–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shier, H. Towards a new improved pedagogy of “children’s rights and responsibilities”. Int. J. Child. Rights 2018, 26, 761–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lundy, L.; Cook-Sather, A. Children’s Rights and Student Voice: Their Intersections and the Implications Forcurriculum and Pedagogy. In The Sage Handbook of Curriculum, Pedagogy and Assessment; Wyse, D., Hayward, L., Pandya, J., Eds.; SAGE Publication Ltd.: Uttarakhand, India, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Osler, A.; Solhaug, T. Children’s human rights and diversity in schools: Framing and measuring. Res. Comp. Int. Educ. 2018, 13, 276–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rau, C.; Ritchie, J. Ahakoa he iti: Early Childhood Pedagogies Affirming of Māori Children’s Rights to Their Culture. Early Educ. Dev. 2011, 22, 795–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCluskey, G.; Riddell, S.; Weedon, E. Children’s rights, school exclusion and alternative educational provision. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2015, 19, 595–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Quennerstedt, A. Children’s Human Rights at School—As Formulated by Children. Int. J. Child. Rights 2016, 24, 657–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, J.A. Diversity, group identity, and citizenship education in a global age. Educ. Res. 2008, 37, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reay, D.; Crozier, G.; James, D. White Middle-Class Identities and Urban Schooling; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlenko, A.; Blackledge, A. Introduction: New Theoretical Approaches to the Study of Negotiation of Identities in Multilingual Contexts; Pavlenko, A., Blackledge, A., Eds.; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2018; pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, D.; Dam, L.; Legenhausen, L. Language Learner Autonomy: Theory. Practice and Research; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, S. Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices; SAGE in association with The Open University: London, UK, 1997; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, S. The West and the rest: Discourse and power. In Modernity: An Introduction to Modern Societies; Hall, S., Held, D., Hubert, D., Thompson, K., Eds.; Blackwell Publishing: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1996; Available online: https://www.wiley.com/en-us/Modernity%3A+An+Introduction+to+Modern+Societies-p-9781557867162 (accessed on 30 May 2021).

- McIntosh, P. Reflections and Future Directions for Privilege Studies. J. Soc. Issues 2012, 68, 194–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutland, A.; Cameron, L.; Jugert, P.; Nigbur, D.; Brown, R.; Watters, C.; Hossain, R.; Landau, A.; Le Touze, D. Group identity and peer relations: A longitudinal study of group identity, perceived peer acceptance, and friendships amongst ethnic minority English children. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 2012, 30, 283–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawabata, Y.; Crick, N.R. Direct and Interactive Links Between Cross-Ethnic Friendships and Peer Rejection, Internalizing Symptoms, and Academic Engagement Among Ethnically Diverse Children. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minority Psychol. 2015, 21, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tropp, L.R.; O’Brien, T.C.; Migacheva, K. How Peer Norms of Inclusion and Exclusion Predict Children’s Interest in Cross-Ethnic Friendships. J. Soc. Issues 2014, 70, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darmody, M.; McGinnity, F.; Kingston, G. The experiences of migrant children in Ireland. In The Experiences of Migrant Children in Ireland; Williams, J., Nixon, E., Smyth, E., Watson, D., Eds.; Oak Tree Press: Cork, Ireland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Boas, F. Anthropology and Modern Life, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, J.P. Social Linguistics and Literacies: Ideology in Discourses, 4th ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gee, J.P. Reading as situated language: A sociocognitive perspective. J. Adolesc. Adult Lit. 2001, 44, 714–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunderson, L. Different cultural views of whole language. In Critiquing Whole Language and Classroom Inquiry; Boran, S., Comber, B., Eds.; National Council of Teachers of English: Urbana, IL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Yau, N. Celtic Tiger, Hidden Dragon: Exploring identity among second generation Chinese in Ireland. Translocations 2007, 2, 48–69. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, B.B. ProQuest. In The Structuring of Pedagogic Discourse, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2003; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P.; Passeron, J.-C. Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture; Sage: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, B. On the classification and framing of educational knowledge. In Knowledge, Education and Cultural Change; Richard, B., Ed.; Tavistock: London, UK, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Cultural reproduction and social reproduction. In Knowledge, Education and Cultural Change; Brown, R., Ed.; Tavistock: London, UK, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- McGillicuddy, D.; Devine, D. “Turned off” or “ready to fly”—Ability grouping as an act of symbolic violence in primary school. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2018, 70, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P.; Thompson, J.B. Language and Symbolic Power; Polity in Association with Basil Blackwell: Cambridge, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Machowska-Kosciak, M. “He just does not write enough for it”- language and literacy practices among migrant children in Ireland. In Multilingual Literacy; Breuer, E.O., Lindgren, E., Stavans, A., Van Steendam, E., Eds.; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- McGillicuddy, D. “They would make you feel stupid”—Ability grouping, Children’s friendships and psychosocial Wellbeing in Irish primary school. Learn. Instr. 2021, 75, 101492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timoštšuk, I.; Ugaste, A. The role of emotions in student teachers’ professional identity. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2012, 35, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, B.C. Learner Identity Amid Figured Worlds: Constructing (In)competence at an Urban High School. Urban Rev. 2007, 39, 217–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollway, W. (Ed.) International Journal of Critical Psychology 10: Psycho-Social Research, Editorial. International Journal of Critical Psychology; Lawrence and Wishart: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Enriquez, G. Embodying exclusion: The daily melancholia and performative politics of struggling early adolescent readers. Engl. Teach. Pract. Crit. 2011, 10, 90–112. [Google Scholar]

- Bunnell, T.; Yea, S.; Peake, L.; Skelton, T.; Smith, M. Geographies of friendships. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2012, 36, 490–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallon, B.; Martinez-Sainz, G. Education for children’s rights in Ireland before, during and after the pandemic. Ir. Educ. Stud. 2021, 40, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Child Participants | Parent Participants | Teacher Participants |

|---|---|---|

| Kasia (12) | Agata Adam | Peter (previous English teacher) Debra (current English teacher) Ann (Maths teacher) |

| Wiktoria (12) | Ala Rafal | Gretta (ESOL teacher) Danuta (Polish teacher PWS) |

| Janek (14/15) | Ewa Marek | Paul—Maths teacher Ann—English teacher Adam—Polish language and culture teacher (PWS) |

| Marcin (13) | Anna Patryk | Debbie (Primary school teacher) |

| Mainstream Schooling Context Monolingual Educational | Heritage Enriched Educational Context Bilingual Education |

|---|---|

| English langugage mainstream school (EMS) (n = 2) | Polish weekend school and English language mainstream school (PWS + EMS) (n = 2) |

| Quantitative Data Collection | |

|---|---|

| Instrument | Themes Explored |

| National survey of teachers (n = 685) | Demographics

Ability group assignment Curricular and pedagogical practices, Definitions of “ability” Pupil experiences of ability grouping |

| Child questionnaire (n = 93) | Classroom organisational practices Ability group practices Child culture and peer dynamics Self-image and self-perception Teacher interaction and bonding to school |

| Qualitative Data Collection | |

| Child focus group interviews (n = 89) | Ability group practices Child culture and peer dynamics Self-image and self-perception Teacher interaction and bonding to school Attitude to intelligence |

| Child sociometric survey (n = 100) | Instrumental ties (three children chosen to help with work) Expressive ties (three children chosen to sit beside) Proxy of instrumental & expressive ties (three children chosen as your friend) |

| Teacher semi-structured interview (n = 9) | Classroom organisational practices Ability group practices Child culture and peer dynamics Self-image and self-perception Teacher interaction and bonding to school Attitude to intelligence Pedagogy |

| Principal semi-structured interview (n = 3) | Classroom organisational practices Ability group practices Pedagogy Policy and external influences |

| Category | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender Intake | ||

| All girls | 109 | 16 |

| All boys | 104 | 15.3 |

| Co-educational | 467 | 68.7 |

| Grade Level | ||

| 1st | 123 | 18 |

| 2nd | 126 | 18.4 |

| 5th | 98 | 14.3 |

| 6th | 127 | 18.6 |

| Multigrade Junior | 78 | 11.4 |

| Multigrade Senior | 131 | 19.2 |

| School Type | ||

| Infant (Inf-1st) | 10 | 1.5 |

| Junior (Inf-2nd) | 61 | 8.9 |

| Senior (2nd/3rd–6th) | 131 | 19.1 |

| Vertical (Inf-6th) | 480 | 70.4 |

| Category | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Teacher Age | ||

| 20–25 years | 137 | 20.1 |

| 26–30 years | 221 | 32.4 |

| 31–40 years | 136 | 19.9 |

| 41–55 years | 150 | 22 |

| 56+ years | 38 | 5.6 |

| Length Teaching Experience | ||

| Up to 5 years | 272 | 40.7 |

| 6–15 years | 202 | 30.2 |

| 16–30 years | 136 | 20.3 |

| 31+ years | 59 | 8.8 |

| Additional Professional Development | ||

| Yes | 231 | 33.5 |

| No | 451 | 66.5 |

| Ethnic Identity | N | % of Total | Above Average | Average | Below Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Majority Ethnic | 75 | 73.5 | 38.7 | 29.3 | 30.7 |

| Irish Traveller | 6 | 5.9 | 16.7 | 16.7 | 66.6 |

| African | 13 | 12.7 | 30.8 | 30.8 | 38.4 |

| Eastern European | 6 | 5.9 | 0 | 50 | 50 |

| Cuban | 2 | 2 | 50 | 50 | 0 |

| Ms Callaghan’s and Mr Kiernan’s Second Class | Reading Group Level | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child’s Name | Gender | Ethnicity | Second Class | Sixth Class |

| Upward movement | ||||

| Shannon | Girl | Majority Ethnic | Average | High |

| Sophia | Girl | Majority Ethnic | High Average | High |

| Pól | Boy | Majority Ethnic | Average | High |

| Same level | ||||

| Keane | Boy | Majority Ethnic | High | High |

| Odhrán | Boy | Majority Ethnic | High | High |

| Jamie | Boy | Majority Ethnic | High | High |

| Rose | Girl | Congolese | High | High |

| Gabriella | Girl | Majority Ethnic | High average | High average |

| Sally | Girl | Traveller | Below average | Below average |

| JoJo | Girl | Majority Ethnic | Below average | Reading unit |

| Downward Movement | ||||

| James | Boy | Majority Ethnic | Average | Low average |

| Eric | Boy | Russian | High average | Low |

| Ryan | Boy | Majority Ethnic | Average | Low average |

| George | Boy | Majority Ethnic | Average | Low average |

| Tommy | Boy | Traveller | High | Low |

| Jeff | Boy | Majority Ethnic | High | Average |

| Princess | Girl | Nigerian | High | Average |

| Berry | Girl | Majority Ethnic | Average | Low |

| Excluded | Popular | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Gender | Boys | 14 | 25.5 | 7 | 12.7 |

| Girls | 8 | 17.8 | 5 | 11.1 | |

| Ability | High | 3 | 8.6 | 9 | 25.7 |

| Mid | 3 | 11.1 | 2 | 7.4 | |

| Low | 16 | 43.5 | 1 | 2.9 | |

| Ethnicity | Majority Ethnic | 17 | 22.4 | 9 | 11.8 |

| Minority Ethnic | 5 | 20.8 | 3 | 12.5 | |

| Traveller | 3 | 50 | 0 | 0 | |

| Excluded | Popular | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Gender | Boys | 6 | 10.9 | 9 | 16.4 |

| Girls | 5 | 11.1 | 7 | 15.6 | |

| Ability | High | 3 | 8.6 | 8 | 22.9 |

| Mid | 3 | 11.1 | 3 | 11.1 | |

| Low | 5 | 14.3 | 5 | 14.3 | |

| Ethnicity | Majority Ethnic | 8 | 10.5 | 13 | 17.1 |

| Minority Ethnic | 2 | 11.1 | 3 | 12.5 | |

| Traveller | 1 | 16.7 | 0 | 0 | |

| Excluded | Popular | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Gender | Boys | 10 | 18.2 | 10 | 18.2 |

| Girls | 7 | 15.6 | 4 | 8.9 | |

| Ability | High | 6 | 17.1 | 8 | 22.9 |

| Mid | 1 | 3.7 | 4 | 14.8 | |

| Low | 10 | 27 | 2 | 5.4 | |

| Ethnicity | Majority Ethnic | 11 | 14.5 | 13 | 17.1 |

| Minority Ethnic | 3 | 16.7 | 1 | 4.2 | |

| Traveller | 3 | 50 | 0 | 0 | |

| The group to which I am assigned | ||

| High | Mid | Low |

| Boys African High Ability | Girls Mid and Low Ability | Eastern European |

| How I see myself | ||

| High | Mid | Low |

| Boys Traveller High Ability Younger Children | Majority ethnic African Eastern European Girls | Boys Mid and Low Ability |

| How others see me | ||

| High | Mid | Low |

| Boys Traveller African High Ability Younger children | Boys Majority Ethnic Mid Ability | Girls Eastern European Low Ability |

| How teacher sees me | ||

| High | Mid | Low |

| Boys Traveller African High Ability Younger Children | Majority Ethnic Eastern European Mid and Low Ability | Girls Mid Ability |

| Racist Name Calling | Children’s Quotes |

|---|---|

| ‘their colour’ ‘a different colour’ Nigger Black Knacker Brownie Black Monkey Black fat bitch King Kong Paki | “People that are black as well, they call them niggers and stuff” (Rachel-Mountaingrove-White-Irish). “And like do you know different people, they are not from our country and some people slag them” (Paddy-Mountaingrove-White-Irish). “Yes mainly ‘cos of my colour or over something very stupid that doesn’t even make sense. Like we’re just friends and then they just slag you” (Tanisha-Pinehill-African). |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McGillicuddy, D.; Machowska-Kosciak, M. Children’s Right to Belong?—The Psychosocial Impact of Pedagogy and Peer Interaction on Minority Ethnic Children’s Negotiation of Academic and Social Identities in School. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 383. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11080383

McGillicuddy D, Machowska-Kosciak M. Children’s Right to Belong?—The Psychosocial Impact of Pedagogy and Peer Interaction on Minority Ethnic Children’s Negotiation of Academic and Social Identities in School. Education Sciences. 2021; 11(8):383. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11080383

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcGillicuddy, Deirdre, and Malgosia Machowska-Kosciak. 2021. "Children’s Right to Belong?—The Psychosocial Impact of Pedagogy and Peer Interaction on Minority Ethnic Children’s Negotiation of Academic and Social Identities in School" Education Sciences 11, no. 8: 383. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11080383

APA StyleMcGillicuddy, D., & Machowska-Kosciak, M. (2021). Children’s Right to Belong?—The Psychosocial Impact of Pedagogy and Peer Interaction on Minority Ethnic Children’s Negotiation of Academic and Social Identities in School. Education Sciences, 11(8), 383. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11080383